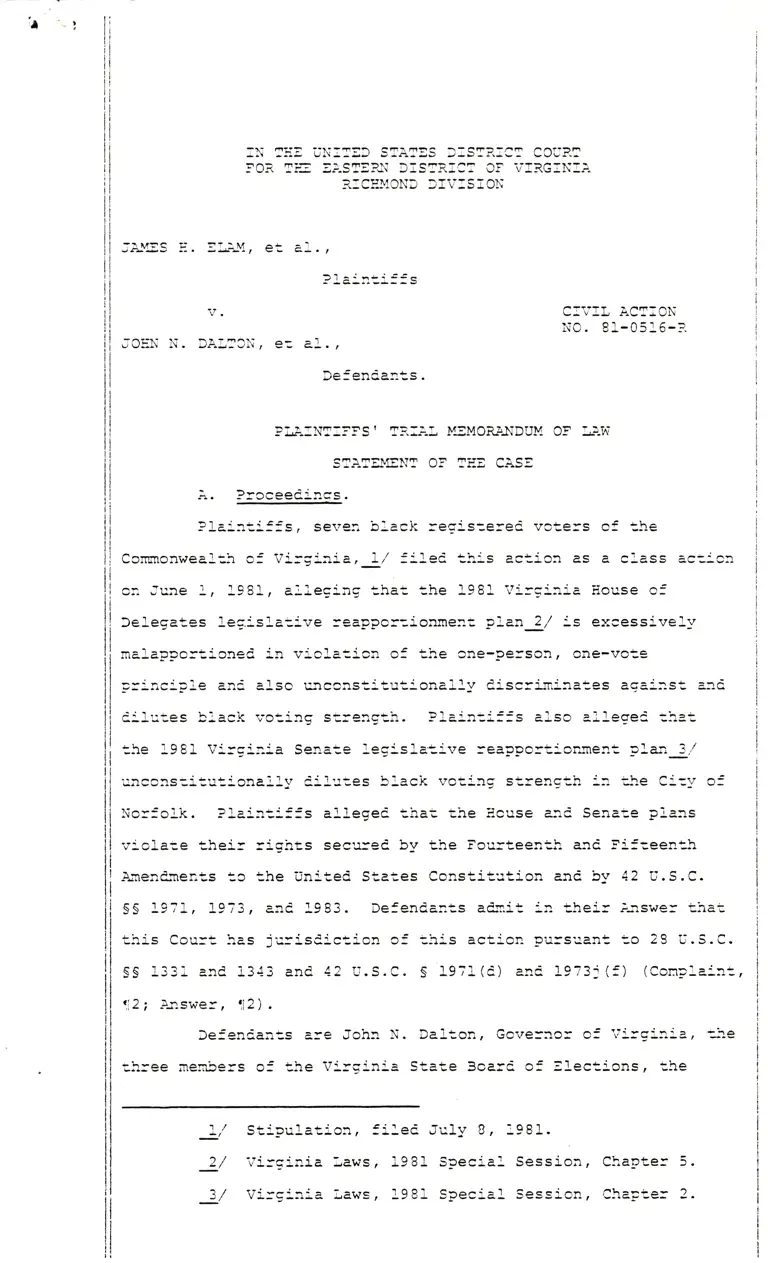

Elam v. Dalton Plaintiffs' Trial Memorandum of Law Statement of the Case

Public Court Documents

July 17, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Elam v. Dalton Plaintiffs' Trial Memorandum of Law Statement of the Case, 1981. c0c2b3eb-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/612db832-c91e-4184-a9d7-3f218a070cdc/elam-v-dalton-plaintiffs-trial-memorandum-of-law-statement-of-the-case. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

a

n-*.F i:\: Tfr=t er?r: mF a a: ct?= ?rrF

^

n i"DF:.t -:f- Ur\::!y iiAA!9 Z-9-lr4e- VVVI'.-

9OF. Ti=

=ESTEPJi

DIS?R.JC? OF VTRGiN=E

R.:CHMOND DTV:SiON

TIMTq TJ' =?-lM 6+

, ve

?1a:n3:-i:s

v.

;OEN' Ii. DAISCN r €-- tsl. ,

aa 3an.i

= n- e

a?tt?? !

^F-

Aa-\-i v J! l{u.L r \rl\

i{o. 81-0515-?.

P].A=NT!!'PS' EF.;AL M3I,{OR-P}TDUI'1 O!' LlI^'

eFlnFMr\Tr"r ntr m-FrF ateE

rr'. ia=CCeeClnqs .

Pl-alrt:-lfs, seven black =egls:erec vo&-€is of --he

Comaonweal:.a oi V!:Ei::ia, 7/ illed '-h:s action as a c:-ass ac::-c:1

on iuae 1, 1981, aileg:i-nE that t,he l-981, virgi:iia llouse o:

)eJ-egates 1eg.:-s1a:ive reappo=:ionmert pl-ar. 2/ :s excessiveJ.lz

mal-apportioned in vicl-a--icn o: --he cne-pe=son, one-vo:=

principie ani also 1:nccnsl,itu',i onaI1y Ciscrj-n',!-a?es aqair,st. ani

c:Iu'-es b;,ack voting s:rength. Plain:j-iis al-so aiJ.eged t-r3t'

the 1981 Vl:gir.:.a Sena:e 1eg:sJ-a--ave =eaPPor-ur-onrl€u'- Plan 3,/

unccns:itu',ionaiJ-12 i'ifui'es biack vo-*ing st,rength ::r '..he Ci:12 ci

No=fo]k. ?l-aintlfis a"! Legei '-hat tne llcuse ari. Sena-'e pians

vlola;e '.heir rigi:ts secu:eC b1r 'the Fou:teenth anc Fi-i--een'-h

Amend:nent,s :c the iinited St,ates Constitu'.ion ano b1z 42 U.S.C.

SS !977, !973, anC 1983. Dejendant,s aCnit in their i-nswe: t;la'i.

''.nis Cou=', has jurisCic-,-ion cf --hj-s action pu=suant:o 23 U.S.C.

SS L33i anC 1343 and 42 Ll.S.C. S 1971 (i) ane 1973,- (f ) (Conpia:n:,

',i2 i }-nswer , ',12) .

Dejeniants are John N. Da1:on, Gcrre=:or oi Vi=gi-r!a, -.:le

three menbers o: the V:=qinia Sta"e Scarc of Elect.ions, the

_L,, St:-pulatior, f:-lee July B, :.981.

2/ Vi=ginia Laws, L981 Special Session, Chapte=

J / Vi:E:.nia Laws , 19 81 Special Session , Chapte= )

)

P:es:ien'- of the Vi=g:n!a Senate, and :he Speake: of the

V:=girla liouse of Delega--es, }'il, t:re de jenoan:s are suec in

the j.: of iicial capacit:-es. On June ?2 , d.ef end.an--s f ile{ '-heir

Answer denying 3he ccnstl'-utional ani sr-a:utro=}2 violat.icns ailegeC

.in rha rraqnl=iri-

-aag

9Vlllv-g--. e .

Cn June l-1, 1981, --h:s Cou=: ente=ed an Oroer consol,lcat-

lrg '-i:-s case wlt,h Cosner v. s!g, Civj-i No. 81-0492-?,, @

Cause v. Dal-ton, Civl1 No. 8L-0530-R, GraveLy v. Da1ton, Clv:-I

Nc. 81-0552-8., and 3Lv v. Anderson, Crv11 No. 81-0L4S-Roanoke.

3he Court, also o=dereC expeCited, proeeeClngrs, and ordereC that,

thls case would be hearC cn st.ipula'-ions, oe bene esse oeposi-

--:cns , ani, exa:bi--s.

Pu=suani to -,hj.s Court's Crie: expecl''ing proceeCingrs ,

depos:-t,j-ons ani, ci-scoverl' proceei.ings concrrenceC on Jr:ne 23 ane

were completed on Ju11z 5. The deposi'-:-ons and other exhibrts

of --he pa*j-es in the va=ious act,j.ons were frled with the Clerk

anC serzed oa the members cf t,he i,hree-judge Dist,rict Ccurt on

July 10.

ts. Sia=emen-, cf -,ire F'accs.

1. Leqislati-ve Proeeei.inqs.

we=e

wh:-ch

Both the 1981 House and Senate plans challengeC be=e

passed b1z

"he

1981 Special Sesslon of '-he Vlrgin:a Assembly,

began on March 30, 198i.

In February, L981,, the Chai=nan of the llouse Privileges

a::c Electi,ons Comcni.t:ee (herelnafter P ani, E Cornmi',:ee) announcei.

a series of public hearlngs on llouse anC Congressional redis-

'-rict,:-ng to be hel-d in Ma:ch.. 4,/ Se'ren public hearingrs were

heLd in NorfoLk, South Boston, AbingCon, Roanoke, liarrisonbu=g,

3ai=fax, and RichmonC. The Ccrr6naE'.ee heard f=om inc'.:reben'-

nembers of the llouse and -sena:e, public o:fi,ciaIs oi count,:-es

anC ci'-ies, leaders of various orgraniza-rions, int,eresteC menbers

1/ The legisla--ive his:or1, of --he 1981 House plan

of iicial-Eocum€rr-us are ccntained in Virqinj-a's S 5 , voting'

Act, submission tc the U.S. Departnent of Just.lce, EIam

Piaint:.'fs' Ex. P-3, Att,achraent 17 .

a-nC

Richts

-3-

of '-he pu-blic, and f ron a numbe= o! black Leaoe=s anc black

ccrununity' =epresencaiives._!/ Fc11cw{ng the pub3.:.c hea:ing in

R:chmonc on March 20, the licuse P arc E Conrni:+.ee heLC its f irs--

mee:ing t.c consider possible C=ait proposals. A subconu::rit',ee ox,

ilouse =ei.ist=iciing was appoin--ed, ani va=ious plans anC

proposals we=e cons:,ierec1. Ac-.:.ng on '-ire recomrnenoat:,ons oi

tne suDconmi:tee, --he P anc E Conunit:ee adopted a plan (the

"?aj-rfax L2'' pian, subcomrittee subrnission) t.o ses/e as a

p=opcsai f or C:scussion, whj-ch was pref:-led on March 30. A

publtc hearing was hel-C in RichmonC on Ma=ch 31 oD this Hcuse

bali, anC f oI!.ow:-ng thrs hearing, the Eouse P and E Conmr'ittee

heLc. addj.tionaL meet:.ngs.

on Mond.ay, Aprrl 6, the Conm,i+-tee was presented with

acCi-.ional pians, anC afte= comirtlt:ee deLibe=ations, which

incluoeo a closei execut,j,ve sessicn from which the Press anC

mernbers of '-he public we=e excluoee 6,/, app=cved a plan labeLled

"tsL Fairfax L2" U bv a vote of 18 to I without anlz written

suppo=t,{ ng statistical data describlng the d.ist=ic*-s or stating

5/ Transcripts of the pubLic hearings are incluoed in

Eiam Piailntijis' Ex. i-:.

6/ Deposition oi Del. Ei:-se B. Iieinz, July 3, 198L

(hereinaEer Hej.nz dep.), p. 58.

1/ Heinz dep. , Exhibit 16. AceorCing to press reporL-s,

two pianlwere considereC. One was calLeC the "Fairfax !2" plan

"because it cedes L2 seats to heavily popuLated Fairfax County. "

The other was the "8.L.' p1an, "wj.th the 'B.L.' standing for

'Brctherly Love' because no incumbents seeking re-elect,ion thrs

year will be harmed by 1t." Richmond News Leader, April 7,1981,

p. 5 (Deposltion of ..]uay CcLd.b s' ix. P-1,

Deposj-t,j,on Exhibit, 2). The Richmcnd Times-Dispatch =eport,eC:"wiren a prelininary B.!. pfa coirmit,tee

Sundalz, the initials were sa:-d to mean bro-,-herI1z love. Yest,erd,alr

some cormlit:ee members were salzing that B.L. means 'barelf iegaI.'

RicirmonC Timel:liEp@, April 7, i.981, p. B-3 (id. ) . The use of

confi:::ned by !,1s. Jane l"lorriss, Executive

Director of Conrnon Cause of Virginla, who was an observer of the

commit:ee deliberat,ions. Depositi.on of .fane Morriss, July 3 and

1, 198I (herej.nafter Mor=j.ss dep. ) , p. 26.

-a-

:he popuLation va=lances.3/ Ait,e= '-his vote, Dei. Ellse ts.

Iieinz, a rneraber of --he House P anC I Ccnru.t-.ee, ccnuaitt,ee st.aii,

and one otier oelecat,e CiscovereC that this plan had 101,

delegaies !n violaticn of state Law._!/ Del-. He:.nz reported :n!s

:o '-he Comrniitee Chairrran, anC ihe nex'- day, Apr:-i 1 , the

Ccmri:.'---ee ccnsiderei new plans. At, that mee'-ing the Comrnir:ee

report.ec o1:+- 7 by a vote oi l-5 tc 5 , a new plan known as -.ne

"Mod.:.iieC Bunny Rabbit P1an"g/ which was an amendrnent in the

natu=e of a subst:.tute fo= the p=eviously j-ntroduced llouse

bili .L!/ No wrict,en supporiing statlstical anallzsis of the Plan

was p=esented :o the corrnittee at the tjJne of its act,ion.g/ On

Ap=il I the Couun:ttee sr:bstitute was debat.eC on '-h€ floor of the

House of Delegat.es , a series of 51oor amenCment,s were of f erei,

some of which were aocpteC and others rejeeteC , and the amended

Comrnittee subs',itute was adopteC b1t the House of De]-egates. The

nexi d.y, April 9 , the House biJ-I was reported by the Senat.e

Conrnittee on Prlvileges and Elections aad passed by '-he Senate.

The 198i Eouse pJ-an bill was then signed by Governor John N.

Dalton on April 10.

In f'ebruary, the Chai:-rran of the Senate Privileges and

Elections Ccurnit'-ee aLso announceC a series of prrct-ic hearings

to be hel-C in March on Senate and Cong=essiona3. reaPpor'-ion-

men'- , &' anc ouring March pr:bLic hearings were held in Roanoke,

Northern V!-rginia (DulLes Airport Marriott Hotel) , Richmond,,

_g / Ileinz dep . , pp. 59-5 0 .

2/ Ig. , PP . 5 o-5l- '

!0/ Ig., p. 61 . See District, 29, EIy dep., Dep. Ex. 3.

g/ ELam Plaj-ntiiSs' Ex. P-3, Att,achlnent li .

L2/ Hej-nz Cep., F. 65.

13/ The 1eg:-sJ.ative hls:ory of ',-he Senat,e bili. anC, _--offj,ciaL-documents record,ingr this legislat,ive history are con-

taineC in Virginia's S 5, Voting Rights Act, sr:.linisslon to the

U.S. Department, of iustj-ce, Elan Plaint,iffs' Ex. ?-4, A--tachment,

t7.

-5-

ani Norfolk. Y/ A =lfth public hea=ing was helc in Echrncni,

on !"ta=ch 3 0. Draft pians were preparei by a subcommi--tee on

Senate =eCis'u=ictlng, ani ai--e= Ccnrn:-it.ee de1:cerE+;LonS the

Sena:e P ani E Cornr:it.ee =eport.ed ou-- a bali.. Co:rrnit--ee sub-

sticutes were reccru:11'-'-ei' r1r lhe Senate to the Ccrnmit.-ee on

Ma=ch 31 and ApriJ- 1. Af-.€r i'a:'-her deliberations, t.he

Cc:mrit--ee report.ed out a biil. After f Loor debat.e on April 6 ,

tbe Senat,e adcpted a fl-oor subst,i:ut,e with iloor amendrnents and

def eated an alte-ra;e ilcor substitute ano floor arnend.ment,s. The

Senate bill was referreC to the Eouse P and E Committee on

April 8 , which reported :-t out with an amendment, on Apnl 9.

The Eouse passed the cormj.ttee amenCment, w:th floor amenCments,

cn April 9 , and ihe Senaie agreeC *-o tire House amencments the

same day. The Senat,e bi.ll was t,hen signed by the Governor on

April i-0,

The guidelines adopt.ed by the llouse and Senate for

legrslative =eCistric:ing \/ we=e set out in 1ega1 memo=anda

written by Ms . M.ary Spain, 1ega1 counseL f or the llouse and Senate

P anC E Conrn:-ttees, dateo April 21, 1980 Y-/ and, May 2, 1980, y/

and Cistrlbu',€C to llouse ani. Senate P anC E Cornmitt,ee rnernbe=s.

in Ciscussing the guidelines app!-icab!-e to J-egislative Cistrict,ing

the April 21, 1980 memorandum notes -'he Supreme Ccurtrs decision

in Mahan v. HoweLL, 410 U.S. 315, 93 S.Ct. 979, 35 l,.EC.2d 320

(1973) , sustaj-ning a total deviation of L6.4*, anC warns: "No

14/ Transc=ipt.s fo the public hearings are includeC in

ELam Plaffitif fs' Ex. i-tr.

U/ Deposi--ion of Robert J. .l-ustin, June 30-Ju1y 3, 1981, .-(hereinaf-,-er Austin dep.), pp. 332-33, 339-40.

W Aust,in dep. , Deposi'-:.on Exhibit 2 .

l7/ i\ustin dep., Deposition Exhib:t 3. This memorandum

Ciscusseilthe Supreme Cou=t'i decisions in Clty of Mobile v.

Bolden and City 6f_Rore r. United sta-.es anffirolina

ffirati,ve@nt@ a +-hird memorandu:n,

entl',-Ied "Memoralxd,um Re: Guidelines fcr Justif rcation of

Districts" (Austin dep., Depositj-on Exhibit 4) \.ras Cistri-

buted to iiouse P and E Corunj-i,tee merroers on April 2, L981.

However, th:s Cocument was wri--:en in contenpldtion of litigataon,

to build a reccrd to defend the liouse pLan against litigation

(Austin dep. , pp . 322-25) , Dr. Aust.in CiC not even know who wro-.e

t,he docr.:inent (id., p. 319), ani it, was not Cistr:-buted until- weLl

af'-er the legiilative deliberaticns hao begiun.

-5-

case since Mahan has upheli, as g:eat a ior.-a1 naxj-mum precent,agre

oeviat.ion."!8/ Afte= C.iscussing '-he va=j-ous cases =ai-sing the

malappor--ioment :.ssue, the memorand,um concLud,es :

"5'or '-he tiouse the g'oal, should also be the -.eD

percent Lctal maxim'.rm percentagre oevia:ion. The

iiouse then has the option of cont,inuing the

poiicies uphelC in l4ahan and the use of multi-

member Cist'.i.cts anffi5 result,ant presen/a-,ion

^3 :oLirical subd.ivision in--eErlty. The con-v;i

+-inued appJ-ication of these pclicies can then

be argued to just:-fy a possiSle oevlation of

r.lp t,o L5 percent."y/

This mernorandum aLso listed the f ollow:.ng adCj.tional- guidelines:

maintenance of political subd.ivision bounCaries, protection of

inc'.mbents, Presenuation of balance amongf political parties or

j-nteres', groups, compactness and contiguit]r of Cis-,ric:s, cgn-

sj.dera'-ions based on population grow',h patterns and special

census prcbj-ems, miscellaneous factors such as geographic

featuses, conio:riiing Legislative and Cong=essj.onal Cist=ict,s, and

avoidance of voter confusion, and avoid.ance of Cilution of

minorJ.ty voting st=ength.20/

Dr. Robert J. Aust,!n, a staff membe= of '-he Division of

iegislative Serv:-ces who himself Cid not Craft anlz plans for

corrrnittee considera'-ion, but who testisiei. as the principal

witness for the defendants in support of the llouse anC Senate

plans, listeo the policies or guideiines which he thought were

iollowed in ',he 1981 liouse reCistrictlng process: Cistricts

should be as egual as praeticable i.n population, the prese=vatlon

of loca1 subdivlsions.as entities, to create as many singJ-e-

me:nber d.istricts as possible, retain exist.ing 3.egisJ-ative

Cistrict,s, take lncr::nbency concerns into accoun+-, eonsider

coruruniiies of iD'.€i€st anC natural bor:nda=ies, and nulti-nember

g/ Ausiin dep. , D€p. Ex. 2, p. 14.

9/ Id. , p . 22 . The House P anc E Ccmnrj.t,tee also

releasei. a press =elease in March, 1981, ccntaining the

criteria to be used, in House red,istrictj.ng (Austin dep., p. 341)

which stated: "State legislatlve redj.strieting plans in which

t,he population deviations :ange frcm plus five percent tc ninus

iive percent per dlst:ict (or per Senator or Delegate !n mul-ti-

nember Cj.strict,s) have been hel-i, ccns'uituti-onal-." Aus--in ciep.,

Depos:-tion Exhabi+- 37 .

4_/ Austi:: oep., Dep. Ex. 2, pp. L5-L8.

i.j.st,rj.c'-s, a::C especially in the ru=a1 a=eas , shouli not be

r^^ l^i - 11 /L(Ju ta9.;L/

2 . Malappor'-ionment--The House clan.

The 19E1 llouse plan fa:l-s Eo comply wi'-h the Leeal

guioelines gove=nlng equaJ-:.ty of popula!:,on among cisi,=iets set

cu: in tne staff J,egal memo=andurr of April 2!, L980. Indeei.,

various J-egislat,irre leade=s, membe:s cf '.he House, and state

oi5:.cia] s ad::ai-.t.ed at varicus Limes that the House P anC E

Co:inmi--iee was not, complying with equal popula--ion requi=ements

and that this planr o! plans with similar populat,ion variances,

would not wi:hst,and a court test. Early in the Cornndttee

deijSerat,ions, DeI. PorC Quillen, Chai:rnan of c'he House

=eCist,rictlng subcomrnittee, was report,eC to have sa:-i of a

proposea plan with a total deviat.ion of 20 percent,:

"We're testing t:he cou,.u'r-ii"rri"g-$;":";; ;;;; think rre're

pushrng the court as to whether '-his (folLows)

the one-man 2 oD€-vote ccncept . " ?/

On Ma=ch 29 , DeI. l{ary Marshall was quoted as f ollows :

"'Ehere are those who may propose plans that

won ' t be uphe ld by the c ourt,s r s o that we

could hol-d our elect,ions under the presen',

pIan,' salzs Del. Mary l"larshaLl (D-Arlington).

'That. way they keep their seats for another

session.'"23/

therwhe

On March 31, Cefendant House Speaker A.L.

to have been unhappy wj-th the variances in

which were similar to the variances in the

Philpo'.t was reporteC

the !{arch 30 bill--

final plan:

L/ Austin dep., pp. 28-30.

22/ Newpor', News Tlrnes-Herald, March 21 , 1981 , 9.4(colCberfldep lhe Virginia Genlral

Assembt lz does not transc=ibe or keep minutes of conuni''tee

oeLiberaticns or flocr debate on biLls (Austln dep., pF. 335,

337). In the absence of official records of legislati.ve

i,eliberations, contemporaneous newspaper a=tj-cles are admissi5le

to snow contertporaDeous statenents made b1z legislators. Hal1 v.

St. Ilel.pna Pa=ish School tsoaro , L97 F. supp . 5i-9 , 652-53 (ffi

La. 1951). (ci:-ree-3udge cour:)l aff ld, 358 U.S. 515 (1952); Lgewen

v. Tui+ipseed, 488 F. Supp. ll:E-fTleg (N.D. Miss. 1980); Sffi

v. Walle.r, 404 F. Supp. 206, 2!3 (N.D. ldiss. 1975) (three-juoge

couiEFSee Fed. R.

- Evid. , Rule 902 .

D/ Washing.ton Post, March 29, 1981, p. c4 (id. ).

-8-

"!'leanrwi:i1e , Eouse Speake=, .l,. L. Phllpo--t saii.

he ls ulhappl' w:-t'h a :enta"il'e Hcuse =e4ls-tr:c--!ng p)-an because he rnalnt.ained it migh:

not meet va=iance guioel:-nes es--ablisheC by

feqe=a1 cour',S."21/

Siril}ar st,at,ements \{ere attributed t,o House P anC E Comn:---tee

Chai:=ran Joirn D. Gray:

"In the 'ace cf alL this, House paneJ- Chaj--ran

.ohn D. G=ay of Hampton conceded, :o r€por-u€rs

that the plan approved bv the Conrni:t,ee Suncalz

would have tc unde=go major surgery to rneet

oD€-$tsD, one-vcte stanCari,."U

The major archltec'- of t,he "brcthe=1y love" plan, DeL. C.

liard,away Marics, inCicated that the plan haC a total d,evision o'-

"about" 22 pe=cen::

"Although the vote vras 18-1 for the proposal,

wlth one abstent,ion, cornrnittee members

expressed concern about whether the pLan

would stand up :-n court if challengeC. " 4/

On April i, the RichmonC Times Dispa:ch reported:

n [House Speaker A.L.] Philpot', periodically

has expresseC concern +-i:,at the conurn:lttee,

which, until ]zes-,-erd.ay, had wrestled incon-

cLusiveJ.y with a wide =ange of pIans, might

not be paying enough atient,ion to one-man,

one-vote rest,raint.s. " 27 /

Phrlpott also specificaily cr:,ticized the varj.anees in the

"Broeherly Love" plan, reported to be as much as 25*z

" 'If you ccme out with such d.eviations as tha',-,

it won't [su::v'ive a cou=', challenge] --that's

for sure,' said tsouse Speaker A.L. Philpott,

before he knew of the plan's other derect."28/

y/ Washinot.on Post, March 31, 19 81 (id. ) .

' 25/ RichmonC TrmeE:Dispatch., April 1, 1981, p. ts-4

(Goidberfldep l.

U-/ Richmcnd News Leader, April 5 ,

Richmond Times-Dispatch, April

1981, p.

i , l_981,

13 (id. ) .

pp. B-1 ,)1 /-'/B-3 (id.):

28/

deP. , DeFT

Washingt,on Post, April

-

Ex. 3.

7, 1981, p. CL (GolCberg

-9-

i:: the floor cela:e on '.he final plan, Delegat.es Elise 3. iieinz

ani V. Ea=i Dickenson bcth criticized the plan ior populat.ion

ieviat.lons too glreat, fcr ccurt app=oval.29/ Ai'-er the pJ-an was

approveC by the iiouse of DeJ-eg;'at.es, Governor John N. Daiton was

report.eC tc have s--ated a'. a meeting of Republican 1eg:-siators

on Apr:-I I that ',he pLan wouli no-, wit,hstand a court chalienqe:

"But, one lawmaker saiC, :he governor maoe

cLear his belief that the liouse plan wiLl

nct, withstanC a eourt chaIlenge. "

"House speaker A.I.. PhiJ.pott saj-d he voted

for the proposal d,espite serious tes€lva-

tions because it was the onJ-1' plan that, could

muster majoritlz supPort. 'If the court

d.oesn 't approve the plan, I hope they | 11 Let

us come back in session to consider it,' he

said . " y/

On Apr:.I 11 the Washington Post reported that the Comnittee's

plan was

"so out of line wj.th S'-B'.€ populat,ion figures

'-hat many irnmediate!.y conceded that it would

fail- inevitable cou:t, challenges. It passeC

the Bouse on WeCnesdalz, then the Senat,e.

"Constitutional problems notwithstanCing,

nc one apgeared reai,y to stop the plan. Not

Iiouse Spe.aker A.I,. Philpott, even though he

acknowleCged that some i,istricts felL far

shy of princj-p1es of equal representation set

by the Supreme Court. Nor Gov. John N. Dalton,

who signed the bilL toCay despite his pr!.vate

preCict,ion '-ha.- it would. fail a court test."L/

Given the Virgin:-a 1980 populatLon3?/ of 5,346,279 to

be apport,ioned among 100 House seats, the popuJ-ation norm for

ideaL-size House seat if absolute populaiion eguality were to

29/ Richmond News Leader, April 8, 1981, p. 1 (Goldbe=g

!ta

be

dep., Deil e*dep. , Dep. Ex. 2) i Richmono Tames:Dis!@,

ex. 3); ilashington , F.

$, April 9,1981, (Dep.

p. cl (ic. ) .

30/ Washington Post, April 9, L981, p. CL (Dep. Ex. 3).

L/ April 11, l-981, p. 85 (iC.).

32/ U. S . Bureau of -,-he Census , L9I0 Census

anC Housilnq, Advance Reoorts, Yiroinia, PHC80-V-48

(Austin dep., Deposi'r-iolr Exhibit 38).

of Populat,ion

I

I

1

I

- 10-

ach:.eveC is 33,463. On the basis of --he p)-an as enac'-ed,33/ and

conputing flote::,al Cj-st=icts acco=i.ingi t.o lhe alIoca--j,on oi I

Ipcpulaticn me',hod,!!/ the 198i House of Delegaies reC:-st=ictj-ng I'l

plan has a iot'al d.eviation--wit,h 51o-,-eria1 Cist=ic:s--of 55.45t.!f[,

Exclucing f loter:.aI districts, :he plan has a tot,al deviati.on of

25.638. Inclui.inq f lote=ial C:-strj.cts calculated accorCinE to

the allocaij-on of populatj.on methoC,

"he

largest va:iances are

5ouni, in Dis:rj.ct, 30 (+40.30t) anC Dis--rict 12 (-L1.15E). ExcIuC-

ing floierial distr:cts, the largest. variances are found in

D:stris-. 3 (+12 .47* ) and District 42 (-14.16t ) .

wit,h floterial- C.lstricts cal-cul,ateC accoriing -.o the

allocatlon of population method, 2! d,ist=icts have variances

of 6t or over, six Crstricts have varj,ances of between 4* and 5t,

ani 23 Cistricts have va=lanees under 4t. Exclud,ing fLoterial

d.istricts, 1,7 districts }lave varlances of 6t or over, 6

cistricts have variances of between 4B and 5*, anC 23 qist,ric'-s

i:ave variances under 4*.

33/ Althouqh the part.ies in the S-=otslzlvan:.a Countl' case,

Cosner vl-DaL:on, have attempteC t.o stipulat,e a change in the

Iffiativffit,ec plan affec'-ing Districts 30, 3L, anc 32, a

f loterial Cistrict whj.ch includ.es iienrico, Caroline, tsanover, and

Spot,sylvania Counties, the methoC by which this changre was

approved by the mernbers of 'uhe General Assembly--a telephone poI1-

fails to ccmply wj.th the Rules of t,he llouse anC Senate governing

legisJ-ative enactments, see Virginia General Asssrnbly, I'lanuaL of

the Senate and Eouse of pS-}g!g. (1980) , and therefore should be

roPerlY enacteC legislative

change. No evidentiary hearing was held in open court on this

proposed change, anC the EIam plai.ntiffs have refuseC to agree

io this stipulation. If EEIs ehange were approveC, District 30

(Henrico County, with three delegates) would have a total poPu-

lation variance of +12.69t, which woulC make that district' Lhe

nost underrepresented district in the entj-re Bouse plan (exclud,-

ing floterial districts calculated according to the alLocation

of populati-on method) .

Presents

arglxnent

34/ The proper aethod of calculat,i-ng floter:.a1 district,s

-E' legal issue which will, be d.iscussed infra in the

section of, '.his memorandun.

35/ The popuJ,at,ion statistics €or each of --he House

i.istrictil and population variances from each district excePt

f loteriaL distrj.et,s , are taken from the state's own calculations,

Austin dep., Deposition Exhibit 5.

VAi.IAI{CES a/ TN TIiE i961 IIOUSE PI,AN

TO iOhES::-

RANKSD TR,OM iTiGiIES?

,li c+*'i ar

30 (jIote=al Cist. )

45 (fioterial Cist. )

!)

41

1

40

43 (floterial d,ist. )

48

1L

10

,)o

28

I

l7

3i (fl,oteriaL d.ist. )

26

36

L0

6

l_8

7

22

1(

Variance

+41.30t

+20.72*

-14.15r

+L2.472

+t-2 . 19 t

+11. 718

-t0.9:t

-10.75*

9.55r

+ 9.458

+ 9.44t

+ 7 .82*

+ 7.67*

/. )J.t

+ 7 .4!Z

1 1?1

+ 5.99*

6.89r

+ 5.83t

6.741

5.08t

-+ 5.988

5.58r

+ 5.518

€

4.85r

+ 4.65t

a / Variances in iloterial Cls',-rj.cts calculated

accord.in!-to the alLocation of population rnethod.

-L2-

D'l =n -.an lrarl !=om Eighest. :o !owes--.Va:i.ances :n +-he i981 House

( cont:.::ueC)

hi c+-.i aly-J b-*E j

2A

??

34

43

2!

8

51

,+

?')

Aq

?o

5

50

L3

38

L2

15

9

11

21

tt

37

Variance

+ 4.35*

.l. ? OleI J . J L'b

< /l*

3.688

3 .47?

3.28r

1 ??e

+ 3.20t

+ 2.83t

+ 2.5LB

2.36*

2.222

2.20*

2.088

2. 01r

1.988

1 ql e

1. 858

+ 1.59t

+ 1.54t

+ 1.07t

0.92r

0.85r

0.13r

The evid,ence shows ihat --he crit,e=icn of keeplng

pot i'-ical subCivlsion bounda:ies intact. canno?- supporr, these

high popula-,lon d.evi at.ions. In =es?onse to plalntlf f s' reques:

f o: p=ocucticn of documen:s, def end.ant,s p=oouced, copies oi- all

plans propcsed to o: considereC b1z both the House sr:bcornrr,it.tee on

red:-si,=ict,ing ani '-he llouse ? ani' E Comlai--'-ee.36/ 1,1s. Juclz

Gold,be=g, of the American Civj-l- Liberties Unj-on of Vlrgiria,

analyzed those plans and found that caLculat.ing flcat,e=s

accorClng io the allccation cf population method and inclui.ing

the East,ern Shore, the House subconmittee and ccrmnit,tee con-

sid,ered but rejecteC 24 plans anC alteraatives wj.th lowe=

populat.ion deviat,ions, excluCing the East,e:=r Shore, consid,e=eC

24 plans, and excLuCing both the Easte:=r Shore ano floterial

d:-s'-=icts, considereC but, re jected 15 plans with lower population

deviatiots.3l/ In add.ition, bo'-h Cor:unon Cause and the NAACP

have prepa=ed p14ns which keep aLI political subdivisions intact,

and wh:.ch have lower populat:-on creviations.3Erl The Cornmon Cause

Plan has a lower total d,eviation of 23.15t incJ.uding fLoterial

Cistrict,s and the Eastern Shore, and d '.otal deviation of only

L5.89t excl-uding the Easter:r Shore.

{/ GolCberg dep. , Deposition Exhibit, 4.

?J_/ Goldberg dep. , Fp. 37-39.

38/ l,lorriss dep., Depositj,on Exhibit 13 (Cornmon Cause

Exiribit ffi. il i Deposition o+ Michael G. Brown, Coord.inator of

Branch and Field ac:ivities for the Virginia S-,ate Conference,

NAACP, July 6, 198L, Deposition Exhibit 2. Mr. tsrown testified

that the total devlation in the NAACP pian vras 17.87t (dep.,

p. 15).

LiS? OF PLA}IS CCNSIDERED BY IICUSE W=TII LOhER !-AR.IANCES,

COUNTING FLCTER.IAL DISTR.ICTS AND TiiE EASTER}{ SHORE (1981

Ilouse P & E Comri.i:t,ee File on Proposal-s for the llouse cf

DeleEates, Go1Cberg dep., Dep. Ex.4).

PIan

Total Variance,

llith Sho=e anc SLoaters

L981 liouse Pl-an 55.45

i,llikins Com:rat.abiJ.ity 47.50

c2u:-ilen 1/2/81 3 5. 8 3

itil-kins (wlth Mioilesex) 35.58

iaster PLan 34.88

Easter Al-*-erna--:.rre +1 34.88

Subconurrittee +1 34.98

Subcornmi.tt,ee +2 34.88

'{orgran Plan 32.9G

Alt.ernative 3 (Sub. +3) 27.51_

PLan -t 21 .06

Plan B 25.G3

Di-scussion Plan 25. G3

Subccmni----ee +3 (Basic) 2G.63

Alternat,ive A (Sub. +3) 25.63

ilte=native C (Sub. +3) 2G.63

ALternative D (Sub. #3) 25.C3

Aiternative H (Sub. #3) 26.G3

Iieinz FLoat,er 25.77

ALternative F (Sub. +3) 22.4L

Alte=native F & !: (Sub. *3)22.4\

Alternati.ve c (Sub. +3 ) Z?.23

PLan C 22.13

Alternative E (-sub. #3) 19.98

ltil-Ler S:ng1e Menber plan L9.43

Alternative E & !' (Sub. +3) 15.40

Heinz 3/31/8t 15.14

ALternat.ive H, C & E (S.#3)15.04

Al,teraative c & E (Sub.*3) L4.81

Morgan Plan A1t.#1 26.63

-14-

-15-

iiST OT' PLANS CONSiDERED BY HOUSE WTTH TOWER, VARIANCES,

EXCLUDiIiG FLOTEPJA;, D:STRiCTS (198L llouse Pile, GolCberc

dep., Dep. Ex. 4).

Pl-an

Total r/ariance,

r.Iith S'hore, urithout gloat.ers

198L llouse PLan 25 .63

-cubecEuxi'---ee +1 26.34

Quillen 4-2-81 23.40

Subcornrrittee *3, ALt.F 22.41

Subcornmittee #3, A1I,.F+H 22.41

Subcornrnittee *3, Al-t. G 22.23

Plan C 22.13

i'7i-1kins Compatabil-ity 2L. 13

l4,ilLer Single-rlecnber Plan 19. 43

i6ltQiiA=iA?irit.

Subeom, #3, Alt. Ii+G+E L5.04

Subcom. *3, F-1t G+E 14.81

vtilklns Compat,. lti-dCleser( L4. 55

Subconcnj.t:ee #3, A1.-. E.r? 14.33

Heinz 3-3L-8L 8. SS

-i5-

3. P,aclai Disc=l;n:nat.ion.

1=) Ear -'ea Dl=-

Uslng i-980 Census figrures :o calcuia'-e the raciai con-

position of Cis'.-ricts, ihe 197! House pJ-an had three majorj.ty

black i,is'-r:cts electing a :ct,al cf se\ren Cirect deIegates.39/

The L981 House plan :educes the number of majori.tlz black

Cistrict.s f rorn three ';o one, a-C the number of deiega'-es elee'.ed

i=om maj cr:.t12 bLack c:s-.racts f=om seven "-o f our .10 /

The majoritlz black iist,=rct,s in the 1971 PIan (basei on

1980 Census Cata) (Submission, At'.achment #5) were as ioliows:

Distrlct Description t Black No. of Delecates

30 Ciry of Petersburg 51.09t

Drnwrd,Cie County (pt)

Prirce George Cor:nty (pt)

33

AC

C:-ty of Fjcirmonc 51.25*

Greensvrlle Countv 53.09t '!

Caty of Emporia

Sussex County

Su=ry County

Charles City Cor:nty

New Kent Count;z

The majori.ty blaek cistrict,s in -the 19Bl- plan (submission,

Att,aci:ment * 7) are as follows:

Disirj-ct Description B Black No. of DelecraLes

3 3 City of Rj.chmond 5I . 2 5t 4

Tbe House oi Delegates elininated these two majoritl'

black d,istrict,s by unnecessarily combj.ning black population

concen-'=ations with J,arge whit,e populat,ion concent=at,ions in new

Di st=ict 28, qnd also b1, unnecessarillz fragmeniiag the black

population concentratj-on in oLd District 45 among five new

ma j ori',y whit,e i,is--rict,s

Y_/ S 5 Submission, Elam Plaintiff ,s Ex. p-3, A--tachment

#6. TheTescriptions of the d.is'.rict.s :.n -.h€ 1971 pian are --Eken

from the Deposition of AIbe=-, Ely, June 25, L981, Deposj_t,ion

Exhibit 7 . The racial sta'-i.stics are ccntained, in the state's

S 5 Subnission.

40/ S 5 Submj-ssion, Elam Plaint,lffs' Ex. P-3, Att,achmen--

#7, containing ihe racj-al population stat.ist,ics lor the 1981

House pIan.

-\7 -

Dist=ict 2E. The Cl',y of Pe'-ersbBrg, which is 51.093

biaci:, has the hlghesr clack popuJ-a--ior, percen+,age cf an!' cit1,

rn Vi=glnia.4!/ In the 1971, pLan, ?ece=sburg was in a slnEle

cls:rj.ct (Dlst:ic-- 30), and Cclonial- lieight.s, which is 98t

wiri'-e ,12/ was rn a s€pdr?'ue cwo-mernber Cistrict w:th Ches'-e=irel-c

Cou:rt_v (Dist=ict 36) .

in its 1981, plan, the liouse cf Delegat,es compietely

el:ninated these pr:o: Cis-.ric'.s, anC ccmblned the black

population ccncen'Lrat,ion :n Petersburg w:-th the white populat.icn

concen'-=atlon !n Colonial lieigh-.s t.c form new Dis'.ric+- 28, which

:s 50.64t white,43/ ',hereby cancelling out black voting strength

.,i i Dara -elr:t--- - '------, .

This new configu=ation was u,nnecessarlz to fo:=r equat 1y

populateC dis'-=icts. Colonial Height,s c oulC have been reta:ned

with Ches',eriielC Co'rrntv !n a '-hree-menber dis',-ri-ct with a

popula',ion varj-ance of only -I.56t .44/ Du=ing the public hea:ing

in lUichmonC on March 20, the Mayor of Colonial Helghts presenteC

a =esolution unanimously passeC b1t the Citlz Council. of ColonraL

iieigh"s requesting that CoLonial Eeigh''s be placec in a sj-ngIe-

menrber Cistric-, with por+-ions of the southe=n part. o: ChesterfielC

Cour:'iy, anC p=esen'.ed testimonlz in support oi the resolut.t-on.a5/

The Mayor test.iiied that, "strict respect for ju=isdictional

bor:nd,aries in our si'-uation Coes serious danage to our poteniial

fo= representation eithe= as ind.iviCuaL cit.izens or as a

1l/ 1980 Census, Austin deP. , Dep. Ex. 38.

4?/ rd.

43_/ Elam Plaintiifs' Ex. P-3, Att,acirment

41/ Ausrin dep., Dep. Ex. 38.

45/ Elarn Plaintiffs' Ex. P-3, Transcript

iieari:rg,Tarch 2l lsic: 20), 1981, transcript and

of Richmond

exhibi:.

-: C-

]-9;i IIOUSE D:SfR;CT 3O

1981 IIOUSE DISTRICT 28

BIack pooulation

5l-.092

popuLation

43 .66*

PETERStsURG

Ffe[ht5

_10-

ccnm'Jn:-.!."46/ Ti:e I{.}-ACP plan shows ti:at Pet.ersbu:g coulC have

been pl-aced !n a '-wo-menber C!s'-=ict wi:n 'ihe Count.ies cf

ts=u::swick, DinwidCie, GreensvlLle, Sussex, anC the Ci'-y of

Empo=ia wj-th a population variance of onl1z -0.958, which would

have been 558 llack in population.!_/

Dis-'r.lc-- 28 viclat.es manl, of the neutral c=iterla

establishei, for ilouse red.istrict,ing. lt'rr,nnecessarillz breaks

up :rrro exi.s'-ingi i.iscricts , it Cilutes black votj,nE streng:h, it,

c=osses ..-he natural bor:noa:y of the Apporaat'-ox River whj-ch

sepa=ates Petersbr:rg from Colonial lieights, and it joins

:ogether 'uwo Cifferent areas with Ciffe=ent cor:ununitj-es of

i::terest and wiin separate nunicipaL gove-rments and separate

school C:-stric-.s.!!-/ Indeed, Dr. Austin concedeC in his oepo-

si-.ion that. the only thing Petersburg and ColoniaL fleighcs have

in common is tha-,- '.-hey are ccnt,igruous cities .49 /

Dis--=icts 27, 35, 41, 46 ani 47. The black popuLa*-ion

in Southslde Virginia is heavily concent=ated in :he four

rnajorlty black counties of Charles Ci:y (i0.62? plack), Su=ry

(52.50t bLack), Sussex (51.02t black), and Greensvil-l,e (55.548

black) .Y-/ fn the L97L plan, all fcur of these cor:nties were

lncorporaieC withj-n Distrlc-- 45, which was 53.09t b1ack.3]r/ In

'-he 1981 plan, Distric! 45 j,s spl-it, up anC fragrment,ed among fi'ze

new majoritlz white i.istrict,s--Disirict 27 (55.34t whit,e) ,

District 35 (68.25* white), District 41 (50.928 white), District

46 (75.51t white) , anC D:-strict 47, a floter:-aI district, which

16/ Richmond hearing transcript, p. 4.

y Brown oep., Dep. Ex. 2.

4A/ Austin dep., FF. 447-51.

49/ id. ,

".

266.

; *ro census, Austin dep., DeF. Ex. 38.

5!/ Elanr P1a:ntj.ffs' Ex. P-3, Attachment #6.

-20-

197] IiOUS: D:ST]t:CT

4-)

NEW KEN?

SUSSEX

,I ILI,E

Total District 53t Rlack

m 50-59? BIack

pooulation

60-593 Blaek

population

70-79t B1ack

nonul-at,ion

N

ffi

kl;;*iri'il;!

I)IS'fRIC't' 46 27.3rrt Rlack

NEUJ KF.NT

FnANK LtNT

Nllw I(IIN'[

UIS AMI}

Ctrvrr FLOA'rntl [)ISTRIC'I' 47- 29.l7A

Black

POouosoN

DI STRTCT 3 5 28 . B 5? Itl ack

lt'

I'1SI[..

\'..,

),.,wt

_,r, o

IGrti'

o

EOF

GTII'.J

r\

\

I

-1

N

I

L"-"'HOPEttrELL

(J pRnrcs

G;CNG5,RINKN

lltl$gna

FETEN

DIN"?IDDIE

N counTt AND r,.

I)rsTRIC'r 4I 48.80t Black

i Ccrnr.lttee who act:,vel1z part.icipaf,ec in ihe de1:-bera'-i-cns of the

I

I Conrnr-r'-ee, acrn:-ttec that the 'ragrnen+.atj-on o! majo=i'-y black

I

I Dis:rict 15 was i.iscussed by P anC E Ccrmj.ttee rnembers in

I

I'I in'ornal- ccnversat.ions in raciaL !e=ms. She tes'-ii:ed. tha:

I

II membe=s acknowLeCqed ',hat the b=eakup of Lhat Cist=ic*- wouli

i.ilu-,e black vctlng s:rength:

"Il was ment.ioned in conversation, althougi: not.

in conunittee d,iscussion, that open season on

- Ray Ashworth's d.istrict, lDistrict, 45] would

involve, anC woulC--disposing of the counties

and c:.t]r, in that Cistrict, woul.d have the

effect. of dilutrng the black vote because that

t{as, other t}ran the City o'- S'-. Pete=sburcr

[sic] , the blackest Cistrict o'. -,-he case.

So, once we Cismani.led, j.t it wasn't,

so bLack anlzmore. * * *"W

"There were one or two occasions in which

somebocy at the conmittee tabl-e remarked that,

for instance, using one or more of the count,ies

in Ray Ashwort,h's district to :iLl out some

otae= dj.strict in the neighborhood certainly

woulC not please the black folks, but that, ls

as jar as i: ever went."54/

The new d.:.stricts viol-ace mos'- i :-'- not, a11,, of '-he

neurral guideJ-ines establisheo b1t the Eouse P anC E Comrui:tee fcr

redistricting. District 4L viol-ates the goal of achieving

population variances of 5 percent plus or mlnus and has one of

'.-he highest population variances in the entire P1an, with a

variance of +9.458 from populati.on eguality.55/ District 27,

which includes Greensville Cor:nty (55.54t black), j.s one of :he

most uncompact dis-.ricts in --he ent-:-re PIan ,-*_/ and Greensville

,2/ }]. , A'ut,achment +7 .

53/ Iieinz dep., p. 83.

31/ Io., p. 88.

y_/ Aus'-in oeP . , D€P. Ex. 5 .

55/ Austj.n dep. r p. 414.

is contiguous w::h Drnwiooj-e Ccu::t1' at a srnail pcir:.: waich

onLy about :wo nlIes wj.ie."7/ As a practical matzer, :he

c.lst:ict !s noncontigucus: t!:ese two counties (Gree::svllle and

DlnwiCdie) a=e sepa=ated by t.he naturaL bouncary icr:ireC by '-he

Not;oway F,i're:, anC there is no higirwalz or b=idge ac=css the

raver at rhat .nc!nt.s1/ Thus, one can no" grc frcrn one pa='- oj

'-he d.:strict '.c another wi:hout, lea'"ring the iist,=:,c--. The

result,ing cisir:.c'.s viol-ate the guidelines on preserving

existing Cis:ricts anC avoiCing vol'er confusion, avoiClng

Cilu-,-ion oi rninor:-t1z vocing st,rengt'h, elimraatiag floteriaL

i:st,=icts (Dis-.=ic--s 45, 45, and 11 make uP only one oi two

floterial Cistricts in the L98l- plan), and. resPect,ing ccrnmunites

of inceres -u .'>9 /

The J,:"" n ani E Ccnrai:tee rejec',-ed alteraatives which

would have avoideC this dilutj-on of black voting srulerlgth. The

Commi:tee's Pj-Ie on Proposals f or the Eiouse of Delegat,es 60 /

cont,ains a draft plan ccnsidereC by the Eouse reCist=ict.lng

subconunitiee (Subccmnittee Plan *2,t which_ proposei. a single-

mernber tsouse Clstrict ior Southside Virglnia which wouLd. have

kept aL1 cor:nties anC cities intact, and wirich was comprised of

--he Corrnties of Greensvil-l-e, Sussex, and Southframp',-orl7 and the

Cities of Enporia anC Pranklin. Thj-s proposeC Cist=:.ct woulC

have had a total population of 52,636, a population variance of

only -1.51t, and a black population majori-ty of 52.81*,6L/ which

closely app=oximates the black pereentage in old Dist=ict 45.

-fl Morriss dep. , p. 32 ..

3,8/ Austin dep., FP. 444-43; DeP. Ex. 14.

,9/ Austin cep., PP. 432-37.

60/ GoJ.oberg deP., DeP. Ex. 4.

6L/ 1980 Census, Austin aep., DeP. Ex. 38.

-24-

SxisilnE LeveLs of biack votirg s:reng--h, wh:le not

ccDS+-l'-ut.rng a major:.t:t, also a:e s:-g:':.lij,cantLlu rei,uced, in

'-h=ee ai,citlonal areas .

Disirict \2. OLd Distric-- 13, ccmposei o! Patrick,

itei:=y, ani P1::slzLvan:-a Coun'-ies and the Ci:y cj Ma=t.insviile,

was 25.1\Z black (L980 Censusl .62/ Thls C:st,:ict was =estructureC

in the 1981 p1an., and Patrick.lf *"rr* Counties aec the C:.'-y of

Ma:tiasvilLe were jo:.ned with Floyd Cor:nty, which is only 3.328

bLack.63/ This realignnent Cilutes bLack votj-ng s-.r€Dgth !n thj-s

area, and result,s in ner's Dis',-=ict L2, whj-ch is onlY 19.958

cl-ack . 64 /

The notes mad,e of the floor debate cn the L9B1 PIan by

t'Is. Mary Spatn, legal. ccunsel for the Eouse P and E Conunittee,

:-nc.icate '-hat Del-. lI. Ward, Teel of Chr:stiansburg argueC --hat

purt,ing Floyd Cor:nt1z w:.th Patrick and lienrlz Cor:ni.j.es dil-utes

m,i:rority voting strength in Distr:.ct L2.65_/ Dei. Heinz also

recalled

cf DanvilLe, vras 29.i4* black.9J_/ In the l98L plan Danville

and Pitislzlvania Cor:nt1z, which a].so is 30t black, a=e combined

w:.th Campbell Coranty, which is oniy 15.10t bIack.68/ This

combination reCuces the black percentage of the Danville Cistrict

from 29.74* to 25.718.69/

the point being made.66/

Distr:cL 13. District 14 in the L97l- plan, composed

62-/ ELam Plaintif f s' Ex. P-3,

63/ 1980 Census, Aust,in deP.,

54/ id. , At,tacirment *7.'

65/ Aus'.-ia oep., DeP. Ex. 43.

66/ Helnz dep., p. 93.

9J_/ Elam Plaintiifs' Ex. P-3,

68/ 1980 Census, Aus'uln dep.,

59/ EIam Plarntiffsr Ex. P-3,

Attachment +b.

Dep. Ex. 38.

Attachment +6.

Dep. Ex. 38.

Attacirnent +7 .

-25-

Dur:ng the floor oebate on lhe l98L Hcuse plan, De1.

.jcseph ?. Crouch oi Lynci:burg "polnted ou-, that the cLack

popuialion ci Danvilfe ani P:,cls1z1vania Counties Isic] is

ccnsiderably larger than the black popuJ-ation of Campbell County,

ihus adC:,ng Carnpbel!. Ccr:nty --o that district would iilu*-e ihe

black voie in Pit:slrlvani.a anC Danvill.e."i0/

Dis--rict 30. C1d D:strict, 32, composed of '-he Ccunties

of Louisa, Spotsylvanla, GoochlanC, and Powhatan, was 23.91*

black unoe= :he 1971 plan (1980 Census fi6:res) .7L/ Tha--

cistrict. is broken up in the new p1an, and Spotslzlvania Countlz

:s placeC wi--h Caroline anc Hancver in new D:-st=ict 30, which :-s

onl1z 18.82? black.72/

Discriminatorv Multl-Member Drst=icts

At the public hea.rings heLC across the state by

the House P ani E Ccnonittee, prior to the 1981 special session,

black wiinesses hrere. unani:nous tha-, multi-member Clstricts,

Partiqrlarfy in the urban areas, denlz black voters =epresentation

of their choice, and that single-member Cistrlc'-s should be

c=eateo. At the lUlchmond hearing on March 20, MichaeL G. Brown,

a staff menber of ',he Virginia NAACP Stat,e Conference, stat,ed

a number of grounCs for preferring single-member Cis-,-rj.ct.s,

l-nc1uc.rnc:

"Minorities have a better opport,unity to be

electeC wi.thin single-member d.istricts and

larel l-ess l-ikeJ,y to have their voting

strengt,h oiluteC. For example, states that

have converted from muLti-member i.is'urlcts

to s j-ngle-member Cistricts, Georgia,

Louisiana, Ter'-nessee and Texas, have had

sharp i::creases in bLack representation."T3/

7 3_/

11 /t a/

i l/

i3/

transcriiT,

Heinz

Elam

p. 16.

dep., p. 93.

Plaintiifs' Ex. P-3, Attachment #5.

Attachment *7.

Plain--iffs' Ex. P-3, Richmond liearing

-26-

A'- the same pubJ-:c hea=ing, De1. B.J. Lanber-., Iif , a black

oelega'-e i=om t,he Ci'-y of Rj.cirmcni, sta'uei,:

"I :.ilink that si-ngle-membe= Cj-stricts in our

urban areas t,hrcughout the entire stat.e

wouLi, assu=e rep=esent,aticn from Lhe mincrity

g=oups and bl-ack as welL. AnC I thrnk that if

anlz way poss:.b1e, a: you couLC have some par'-s

oi Richmond in a s:rgJ-e-membe: Cis',rict, o=

aiL of RichrnonC, some part, of No=f olk --ha'.

woulC make it ver], heipful. So I hope that

you will keep :hat in minC for your p1an."j-!/

A: :he March L3 pubiic hea:ing in Fairfax Coun'-12, Professor

Al-len Rosenbaum, Professor of Public Po1icy at, the University

of Maryland and. a f o:-ner resideni of Virglnia, testified ',-hat

mulii-member Cistricts "work to oenlz citizens their fair repre-

seni,a',-i oa. " p/ lle stated,,

"FinaJ.J.y, it seems 5uo rl€ ti:at muLt:,-nrember

Cistricts do' make your =eappo=+-j.onment

pLans

much more vulnerable tc court challenge, par-

ticularly given that, this State j-s under the

coverage of t.he Voting Rights Act. Certainly

in Ccnnor v. Finch, a Missj.ssippi case in L976,

the@me c6Edeclarec quite clearly that

where issues of race ccme into play, multi-

menrber Cistricts are not acceptable. * * * But,

cer',-ainly if lhere are guestions of race in-

volved and guestions of more than modest

d,eviations in che size of d,istricts, there is

a-bsolutely no guest'ion in m1, mind that the

Supreme Court, will rule against it."76/

Sinilar opposi*-:-on to multi-member dist=ict,s was voiced by

=epresentatives of pubHc interest. groups and by interested

citizens.Tl/

74/ Id., DD. 23-24.

7J/ Id., Fairfax county hearing transcript, p. 55.

1-9/ I<1., PP- 55-68-

77/ See Plaintiff Graveley's Second Set of Reguests

for AdmiFions and Second Set cf Inte=rogratories and girst, Reque

for Proouction of Docrslent,s, fiLed June 30, 198L, Fp. 9-15. "]

AccorCing t,o L980 Census cata, the 3.a=gest, black

pcpulacicn ccncentra--ions :n Vlrgin:.a a=e l-ocated in the la=ge

urban areas:18/

Ct-,]z Elack Populatlon ( 19 8 0 Census )

R:-cnmonC LLz ,357

No=foLk 93,987

Pc=t,smouth 17 , 18 5

Newport. News 45,584

Ilampton 42, A72

?he House P anC E Corranitt,ee had aceess to this Census data rT2/

anC the Committee anC its staff were well aware that i.ividing

these areas into sj-ng1e-member d.ist=ict,s would result in majo=it1z

black Cj-stricts which.would be able to elect, black i.elegates tc

the liouse of De!-egates:

nQ. It is likely, D!. Austin, -Jrat if --he

large r:rban areas of Virginia which have

mu1*,-i-member d.is-'ricts now lrere sr:bd:.vided

:-nto single-rnember Cistricts tlrat some of

those single-member district,s would be

majority black in population?

A. Yes.

O. And -.hat some of tbose singie-member

cistricts would be able t,o el,ect bl-ack

deJ.egates to the House of Delegates?

A. P=esumably so r yes . "'W

In the 1981 Eouse plan, except for Ricirmond which has a

slight black population majority, the black populations of

tirese cit,ies a:e placec in 1arge, majority white single-mernlcer

i,ist=icts. A comparison of these la=gre urban Cist=icts in the

l98L Eouse pian with the single-member district plan prepareC

for the piaintiffs by the staff of the American CiviL Liberties

L9/ Austin deP. , DeP. Ex. 3 I .

12/ Id. , p. 380.

80/ !i., p. 378.

!r

li

-2E-

Union of Virg:ri.a shcws --ha! j-: fal:ly-srawn singie-:llem5er

i.!st.=ict.s had been enact,ec in these urban areas, bfack vcte=s

woulc have had the opportr.rnity to elect candiCates of their

alr ai aaV-aVaV9.

St,a-.e House PIan 8L/

45 llampton

qt ?q1

35.208

45.12r

31.45r

34.313

AC],U Singie-t4ember District Plan 82,/

59 Ri.chmond (Pt) 54-938

Dist,rict Desc=iption

33 Richmond

3i Noriolk

3 9 Port,smouth

48 Newport. News

50 Richmond (pt)

i7 Norf olk (pt)

78 Norfolk (pt)

B B1ack No. of Deleqat,es

i

2

3

2

1 4 .56*

64.55r

57.81r

53 Portsmou'-h (pt) 7J-.792

4E Newport News (pt) 54.11*

Hampton (pt)

44 Hampron (pt ) 50.08*

(b) Senate Plan.

fn the Sena',-e plan the Cistrict bound,ary Ij.ne between

Dj.stric--s 5 anC 6 unnecessarily divj.des the heavy bLack

populat!.on concentrat:on in Norrolk between the two districts,

thus, d.ilutlng black votj-ng strength.

The norm or i.deal-sj-ze populati-on ior a Senate Cj-s--ric+-

L/ Elanr Plaintif f s' Ex. P-3, Attachment #7 .

82/ GolCberg oep., pp. 102-06, 115-40, Dep. Ex.'15;

-\CLU Sinfre-Member District Plan, filed July g, L981 (ELam

Plain+-iffs' Ex. P-8).

-29-

is L33,657 , ano the 93,98i black Persons res:-Cing :-n tio=fol-k 83

consti-,ute a suificlent popuLat.ion rcr a majority black Sena--e

't'r cr-ia& -he black population oi Norfolk is mos: hear,'iI},

concent,rateC rn the majoritl' black precincts :-n the sou:hern

pa=t oi the ca:y. 84/ insteai, cf respec'-ingr this black popuJ,atj-cn

corcent:ation,

"he

bounoary lines of Dls'-rict, 5 anc 5 r'.rn ln a

jagged fashicn =igri:', through '.-he m:.,oiIe oi this clack population

concentration, Clviding it almost, evenly between -.he two

d,istrlcts. 8y Disirict. 5 :s 51.83t wh:'ue, arrd Dist:ic-. 5 !s

59.58t white . 8V

Durj-ng the fioor debate in the Senate, Sen. L. Douglas

trji,Ld,er of Richmond, the only black sena'-or in

strongly critj.cized as raciaLllt motivat,ed this

voti-ng strengith j.n Norfolk:

-.he V!=ginia Senat,e rl

i

i,ivision of black i

I

"'I{hat we're t.a!.k5-ng about !s a sj,tuation that,

d.ilut.es votes, ' Wilder saiC. He added that

No=folk blacks who supgort single-menber

d.istricts must be ':nvisi.SJe menr to tbe

city's Senate delegation. And he saj.d, 'We

haven't injectei racism into Virginia politics

for a long tirne.'"9

Sen. WiLder offe=ed. a flco= amendment to the Senate biLl which

woulC have eguaiizeC popuLation.between the two Norfolk Senate

cistrists without d.ividing up this black population concen',-ra-

',icn, but the amendrnent was oefeat.eo by a vote of 35 to 3.33/

3he proposeC floor amendment would have provided for a majori,ty

black senatorial district which would have been over 52* bIack. 89/

83/ 1980 Census, Austin deP., DeP. Ex. 38.

Y Goldberg dep., pF. 84-91,, Depos!.tion Exhlbit LL.

8s/ Id.

86/ S 5, Voting Right,s Act, sr:bmission of ',he 198L

Senate piEn, Eiam Plaintifis' Ex. P-4, A',-:aci:ment +7.

E/ Richmond Ttmes-Dispatc.!., Apri-I 8, 1981r p. B-3,

G o 1 cbe re-d e p . 7-56F:-Ex]-2.

_g Id. ; Elam Plaintiff s' Ex. 9-4, Att,achment #L7.

8Y GoLcberg dep., p. 90.

CI TY

-30-

oF I.toR.FOLI.:

A

B

I

6

a

) ---a

-

aar!!

Area of over 50t black

popu Ia t ion

ChaDter 2 Senate cristrict-

i:ounclary

.9enator I.,i1Cer i:roposed

cl ist r i.ct bouncia r.,,

5 - .Senate District 5

Black nonulat ion i1 . 67 e,,

5 - Senate Distrlct, 6

Blacl:. oooulation 35. 8a-q

A t.tiLrler ri-i. strict 5

BIack noou.l ation L6 . 7 4 e.

B t,,:Icier d istricr, 5

9l.ack nonular-i.on i?. 85?

-3 1-

A^R'GUMES{T

I. TIIE L981 HOUSE PLAN' IS UNCCNSTiTUTIONAL FOR

EXCESSiVE VAT.iAI.]CE-E FROI{ POPUi,ATICN EQUALTTY.

The Equal Protectj.cn Clause of the Four--eenth AmenCment

"reguires that, a State make an honest and good faith effort to

construct, Cistricts, in bot.h houses of its legislaturer is

near]-1, of egual population as :-s practicable. " Relznol-Cs v. Sims,

337 U.S. 533, 57i, 84 S.Ct. !352, L2 L.Eo.2C 506 (1964). The

goal is "ful1 and effect,ive part.ici-pation by alL citizens in

s'-ate government .n Id,. at 555. The Virginia General

Assembly has failed io compJ-y with constitutional =eguirements

in j-t,s j-981, House reCistricting p1an, both as tc floterial

d.:-str:-cts and as to non-f Lo--erial i,istricts.

A. Malapportlonment in Floterial Disiricts ShouIC

be CalcuLated AceorCing t,o the Allocatj.on of

Popul-ation Method.

Floterial d.lstrict,s are a form of urulti-rnember Cist=lcting

in which one or more legislators are electeC from sr:bCistricts

and one o= more legislators are elected Cistrictwide. Connor v.

E},AE!-, 431 U.S. 407, ALZ n. 7, 9i S.Ct. 1828, 52 L.EC.2d 465 (L9i7

fn the 1981 Eouse plan, there are two flot,eriaL d.:strlcts,

District 32, with Districts 30 and 3:- (subdistricts), and

Dist=ict, 47, with Districts 45 and 46 (subd.istricts). Their

fr:nct,ion i:t legislative reapportionment is to mask or conceal

wide variances in popul-ation arrong d,istricts. Thus, if it is

impossible to aLlocate legislative seats to political srrbdivisions

wj.thin any acceptable range of population equality, several

polit,ical subdj.visions which varl, from the norm in population

may be assigned a float,er, and the argument is presented, that

populat,ion eqrality among districts has been attained.

(1) The State's MethoC of Caleulatinq Variances.

The General Assembllt, in calculating variances in i',s

f loterial d.ist,rj.cts, t=eats these districts as if thelz were

orCinary multi-member Cistricts. Thus, in calculating the

.

popula+-ion va:Lances, the General Assembly add,s togrethe= the

popul.a-,-ions cf =he en--j-re Cist:lct., anC civides by the nusrber cf

delegates assignred to both the fl-oterial Cist=ic-- and the srrb-

iist,=icts to calculate the variance. The floter:-al, Clstrict and

subCis--=:-cts in Dlstrict 32 have the folLowing populations:

Spot,syLvania 34 ,435

102,131 L delegate

District 31, Benriec 180,735 3 delegates

District 32 CaroLine 17,904

Hanover 50,398

Spot,sylvania 34 ,435

Henrico 180,735

,8\ n, 1 delesate

The Vj-rginia General Assombly si:nply aCdeC up the population

cf the entj-re fl-oterial Cistrict, regarCless cf subCist=icts,

and d,ivided by five to calcuLate the population varianee (norm

of 53,463), and dete:ra.ined that the popula-,-lon varr.alrce in':these

three Cist=icts vras onJ.y +5.04t.99/

This metbod of calculation , however, ls extrene j.y mis-

leading . N District, 30 , with 102 ,737 people, has enough popu-

lation for two delegrates, but g:a only one under the 1981 p1an.

On purely arithmetic gror:nd.s, overpopulated (and underrepresenteC)

District 30 is not conrpensateC by electing a share of the

flcterial seat. Because of its population, District 30 is

entj-tled to another whole delegate, but its population is only

36t of the floater district and will have only 35t of the

influence :-n electing the floater. Obviously, vot,ers in Henrico

Cor:nty, with a population of 180,735, will control the election

of the floater delegate, and District, 30 suffers from cLear

underrepresentatj.on in this plan whieh is not revealed by the

traditional method of calculati.ng the population varj-ances.

Dis"=ict 30 Carollne

Hanover

17 ,904

50,398

t{orriss dep., pp. 154-60.

ea/

ev

Austj.n dep., Dep. Ex.

EI]r deP., PP. 48-58;

-3 3-

in add:'-j.on, by i.iviCing the popuiatJ-on of --he lvtrole

clst=ict by the total number of delegaies, this method treats the

vot,ers of Dlstrict 30 as i: they participated in the election oi

the th=ee CeJ.ega:es from lienrico Countlt, which they do no:.

Shis me-,hod of calculation has been eondemned in the

pol:.t.ical science }lierature, see, e.9., P.. Dixon, Ji.,

Democ=a'.ic Representation ,

pp. 508-12 (L958); E.D. Hanilton, Leqislative Constituencies:

Sing1e-Member Districts, Multi-l{ember D:-striets, and Ploterial

District,s, 20 western Po1itical Quarterly 321 (1967); C. Shube=t

anc C. Press, Measuring Malappor'-ionment, 58 Ara. PoI. Sei. Rev.

302 (1954). The den-ial o! egual representation :-n malapportioneC

floter:al, Cist=icts also is justiciable, and several coufr,s have

ccndemned underrepresentation in mal-apportioneC anC unjus',

fiote=iaI C:.stricts. Cf . Mann v. Davis, 254 8. Supp. 241, 246

(E.p. va. 1965), g!}!, 382 U.S. 42, 86 S.Ct. 181, 15 1,.Ed.2i

(L955); Baker v. 9,3E, 247 F. Supp. 629, 640 (M.D. Tenn. 1955),

rev'd. on othel-grc, 359 U.S. 185, 82 S.Ct,. 691, 7 I,.Ed,.2d

553 (L955); Stout v. Bottoroff , 246 F. Supp. 825 (s.D. Ini. 1955);

Kilqarlj.n v. Martin , 252 F. Supp . 404 (S.D. Tex. 1956 ) , rev'd,

385 U.S. L20, 81 S.Ct. 920, L7 t.Ed.2d.17J. (1957)

(2) The Allocation of Population llethod of Calculating

Varianees .

A more accurate method of calculating variances in

floterial d:-st-ricts is 'r-o c?,Iculate each subCistrict's share in

electing delegates. Shis method, more accurately measu:res any

underrepresent,ation or overrepresentation in the floterj-al

arrangement . See E. Hamilton , Legislative Constituences , g!pg:

C. Shubert anC C. Press , Measuring Malapportionglen+-, gpg. This

calculation is performed as follows z 92/

92/ See Corrrron Cause Exhibit No. 1, E:q>lanatory Note.

-34-

8irst, calculate the share each subdist,=ict has ir '-he

elec'-ion of '-he floa',er. In the L981 House p1an, Dist,=ict 30

has the folJ-owing sha:e:

Sr:bcistrict popul a'-ion

FloteriaL dist. pop. - <I\

Second, add .Ln the C:rect representat,ive. In :his ca'S€ r

the population of Dist,rict. 30 has 1.35 de!-egates, one Cirect

delegrate plus .35 share in electing the fLoa'-er.

Third, Civide the subdistrict population b1, the delegate

figu=e to calculate the popula-.ion va:lance. Be=e , L02,737

oivioed by L.35 delegat,es equa3.s 75,542 popuJ-ation, whj-ch is

+41.30t above the no=n of --he ideal-sized Cistrict,. fn this

plar:, then, District 30 is underrepresented by _41.30t, and

Dist=ict 31 is oveEepresented by a var:-ance o! -7.13t.

Using this more acsurate method, of calcuLation, +lte

fLote=ial Cistricts in the IgSL Eouse plan are malapportioned

As a lega1 matter, resolving this j,ssue in favor of the

plaintiffs is not foreclosed by the Supreme Courtrs decision

in l,lahan v. Eowell, 410 U.S. 315, 93 S.Ct.919, 35 t.Ed.2d 320

(1973). In Mahan, the District Court refused, to resolve this

issue because it concluded that a total devia'-ion of L6.4t

without calculating the floterial d,istricts was "suffici.ent to

condemn the plan." 330 F. Supp. 1138, 1L39-40. The Supreme

Court simply saj,d that it would "decline to enter this irnbroglio

of mathmatical manipulat,ion" and determined, to "confj-ne our

consideration t,o the figures actua1ly found by the ld,istrict]

Court and used to support its hold,ing of unconstitutionality."

410 U.S. at 319, n, 6.

by the followlng population va:iances:3V

District 30

District 31

District 45

Distriet 46

+41.30t

7.13r

-10.75r

+20.12*

-g E1y dep. , Dep. Ex. 9.

3he matter cannot, be put asice he=e, because the

mal-appo=tiorr:nent in ilot,eriaL Cis'-ricts severe].l, aifeets'-he

euan-ul::ti of =epresentation to be aceordeC '-he populat,ions cf

nlne ccuirt,ies and cit,ies !n the General Assembllz which a=e

severeLy underrepresent,ed ir the 1981 Souse pJ-an.

B. The Population Devialions in :he 1981 llouse PLan

Exceed Constitutional L.i-mitaticns.

=he

popula+-ion oeviation with flo'-e=ia1 Cistrict.s of

55.16t exceed,s the hrghest population devia'.ion ever approved

by'-he Supreme Court. (15.48 in Mahan v. ilowelL) by 39 Percentage

poin--s , anC the populatj.on dev:-ation of 26. 63t excl-uCing

floterlaf Cisi=icts exceed.s the highest popuJ.ation deviatj-on

eve: approveC by '-he Supreme Court by 10 percentagre points.

3oth d.eviations exceeC the toial population deviati-ons hel-C

uncons--itutional blz the Supreme Cou=t an G-193*i3 v. r:iLl, 385

u.s. Lza, 87 S.C--, 820, L7 L.Ed.2d.77:- (1967) (26.48t); Swann v.

Adasrs, 385 U.S. 440, 81 S. Ct.. 569, L7 t.Ed.zC 501 (1957)

(25.55t) ; Whitccnrb v. Chavis , 403 U.S. L24, 160-63, 91 S.C'..

1,858, 29 L.Ec.2d 363 (1971) (24.79t); and $rc. v. f?i9i, Qa

u,s. 1, 26, 95 S.Ci. 751 , 42 L.Ed.2d 766 (1975) (20.148). fn

these cases ',.he Supreme Court aPPears to have adopted the

p=incipJ.e that population deviations over 20t are per se trjilcoD-

st,itu'.iona1, and no plan with population deviations that high

can withstand constitutional challenge regardless of the

just,ification #or the high deviation. Certainly none of the

justifications advanced in those cases, includ,lng the goals of

obse:rrj-ng geographical bor:nd.aries and exist,ing political sub-

Civisions aCvanced in Chapman, supra, 420 U.S. at 24,W were

held sufficient to sustaj.n such gross inegualit'ies of

populat,J-cn among di-stricis.

y/ Although Chapman involved a court-ordered plan, and,

thus was evaLueted according to the strj.cter standard,s of PoPu-

latj.on eguality applicabJ,e to such plans, the Suprerne Court held

that the popula-,-ion deviation in that case did'not even meet '.he

mcre liberaL stanCarCs applicable to legis j.atively-enact,ed pIans.

(footnote continued next page)

Fu=ther, it j-s clea= irom this record that the General

Assernbly srraply has faiLei, to make the regui=ei "hones'- ani'

grood laith efiort" to achieve egual:.--lu of population alnong the

Ci.s--rict,s. Numerous plans with lowe= variances vrere 'i?rcDoseo which

I

I

kept political subd,ivis:,cn bouniaries iniact,, but hrere rejecteq by

rhe liouse P ani E Commi:tee. No member of the Bouse cf Delegates

or the llouse P and R Cornnritt,ee has testifieC for the deienCan--s

'-hat -'he policy of maintaining poJ.iticaj. subd,ivision lines

Cictates the population inegual.ities present :-n this plan.

The def endan'-s ' principal wi.tness on this issue , Dr. Austin,

iest,:.fied that -.-his c=lterion is based on the lack of legisl,ative

powe=s ent=usted to Virginia's ccr:nt.ies and, cities r:nder

Virginia's system of i-nd,ependent cities , whose legisJ-ative neeCs

must be met by reliance on locaL legislat.ion introCuced by

members of '-he General, Asserobly. But this goal is virtualJ,y

iropossiJcle tc accomplish irr a s'.-at€ where the population is

unevenly Cistributed Ermong 9 5 cguniies and 4l independent c!:ies

from which L00 oeJ-egat,es must be electeo. AccorCing to the

1980 Census, a total of 22 jurisdictions, 10 cities and L2

counties, have populations which exceeC the norm for a Bouse

d,istrj.ct,, and 31 cj-ties and 83 counties have populations below

this Dorm.

"Tbe policy of maintaining the inviolability of

county lines in such circumstances, if strictl-y

adhered. to, must inevitably collide with the

basic equal proteetion standard. of one person,

one vote." Coruror v. Finch, supra, 431 U.S. at

419.

-

As the Suprerne Cour'- has made clear on Dumerous oceasions,

"Recognit:-on that a State may ProperJ-y seek to

protect the integrity of political subCj.visions

or historical boundary lines permit,s no nore

Footnote g eontinueC.

"Examination of the asserted, justifications of

the court-ordered plan thus plainly d.emonstrates

that it fails to meet the standard,s established for

evaluating variances in plans forrnulated by state

legisj-atures or other state bodies. The pIan,

hence, would fail even r:nder the criteria enun-

ci.ated in Mahan v. Ilowell and Swann v. Ad,ams."

420 U.s. ailf

_ .- r..i-i'

-35-

'-i1an 'minor devia--ions' Srom the bas:-c

-o-li=ement tha',- Iec:-slati,ve iist=:.cis must,

- -=---

b-..---

be 'as nea:ly of equal population as is

pract,icable. "' Rornan v. Sincock, 377 U.S.

695, ilo, 84 s.cEIEca, ffi.za 520

(1955); Retrnold.s v. Sims, EgEIB, 377 U.S.

at' Sji; Connor v. pinch, W,, 13L U.S.

at 419.

Ln Mahan v. @1I, !!Ei, the Supreme Court he1d, that.

the goal of nalntaining poli'-icaI subc.ivisions as Cistricts in

Vi=ginia sufficed to justify a L6.1t population deviation in the

1971 plan for '-he Virglnia House of Delegates. The holding in

that case cannot be useC to support the gross population

deviations present in this PIan, however. In Mahan, there was

txlcontrad.icted evidence--wh:.ch is not Plesent here-that '-he

legisla--Br€'s plan "produces the minimum deviation above and

below the norm, keeping intact poJ-ilica1 boundaries. " 410 U.S.

at 326 . By contrast, the alte:=rative plans submitteo in this

case show that much smaller variances caD be achieved even

keeping political boundaries in''BCt. The Cour'- also ind.icated

that the 15.4t devj-ation sustained in that case "may well

approach tolerable l-imits." Id. at 329.

The 1981 Eouse plan should be declared, unconstitu'-iona1

for failure to meet the one-person, one-vote reguirements of

ReynoLds v. Sims and its progeny.

. :I. PR,OBECTTON OF TN9JI'{BEI{TS IS A!{ I!,1PERI,IISSTBI.E

RACIA! CRITEP.IOI; T'OF. REDISSR.ICTiNG iN VIRGTNIA

Robert, J. Austin, arr au--ho=it1z in Virginia reappor'-ion-

ment and t,he pr:-ecipal witness fo= oefendants j.n this case,

ind,icated that '-he p=otecticn of incumbents is a primary

no--i.vatlcn for the retent:on cf urban mult.i-member Cist=i-c''s

in :he House plan.9,/ This criterion was a primary factor in

lhe development of the chal1enged House plan .96/ lhis cri-terion

is a covert racial classif ication. That ',has c=i-.erion does not

contaln an explicit racj-al classiflcation is of no consegueDce

because the c=iterion is not neutral; it is analagous to the

st,atut,e considereC in Personrrel Adm'r of Mass. v. @., 442

U.S. 256,99 S. C:. 2282, 60 i.EC.2i.870 (!979) where the Supreme

Ccurt clearly ind,icated that:

' [i] f the lchallenged statu'-ory] classif ication

itsel-f , cpverr or.ovefr,f .is not based upon

gender, EEe second question is whether the

icverse effect, reflEEffiicious gender-based

Clsc=i"nination." IC. at 274 (emphasis adoed).

In this instance,'.he record, shows bo',-h that the criterion is a

coveri, racial cl-assification and that the ad,verse effeet, o! this

criterion reflects invidious raciaL Ciscriminatlon. of course,

the cove*, racial cLassificatioi alone is sufficient to find

this criterion unconstitutional. Nevertheless, the aCverse effect

of this c=iterion is Ciscussed at pp. 25-28, supra.

The evid.ence in this case shows that this criterion

creates a racial. classification prohibit,ed by the Supreme Cou=',:

[T] he State may no mcre Cisadvantage any

particular group by making it more difficult

to enact legislat,ion in its behalf than it

may dilute anlt personrs rzote or give any grouP

a smaller represent,ation than another of com-

parable size. Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S.

395, 393, 89 s.ffiz, zffia 61G (1969).

As was true of the statute in Lee v. Nlzquiest, 318 F.Supp. 71,0

(W.D.N.Y. 191A), aff 'd, 402 U.S. 935, 91 S.Ct. 1618, 29 L.ed.2d

L05 C1971), this criterion frustrates minority participatj.on; it

-r

96/

Austin dep. ,

Austin dep. ,

p.

p.

376.

29.

-3 8-

"operat,es to d.isadvantagre a m,inori:y, a raciaL :rninori:y in the

poI:,t.icaI p=ccess . " 3 L8 P . Supp. E-r- i20 .

The most recen'- decision applying t.his 1ega1 st,andard is

Seatt,le School Dist. No. i \'. St,at,e of Wash., 633 F.zC 1338

(9ti: Cir. 1980) , af!'9, 173 F.Supp. 995 (w.D.D.C 1979) . Thai

Ccur-- held that, a stat,e statute was unconstitutionaL because it

c=eated an impe:-nissible legisJ-atlve classification baseC on

rac:al crite=:.a even though the s'-atute Cid. no-u cont,ain atl

explicit =acial classificaticn. 633 P.2d at L342. The

challengeC statute enumerat,ed pu:poses for which school d,istrlcts

may assignn s--udent,s to schools and omitted from that enrtrneration

the assignment, cf students in order t,o achieve =acial balance.

Emphasizing the importance of protect,lngi agai-nst eovert racial

classifj-catj.ons, the Court said:

"Unless this Court affirms the relevancy of

the constitutional analysis in Bunter and

Lee to this case, the guaranteel6ffiual,

lFot,ection of laws will become a hollow

shell." 633 F.2d. at, L344.

Applying these principles, it is manifest that proiection

of incr:mbents creates a constitu',-lonal1y-suspect, racial classi-

fj,cation. The incr:rnbents benefitt,ed by tbj.s criterion are

ove:mhelmingly white. Of 100 delegates, onJ,y four are black;

of 40 senat,ors, only one is black. The primacy of this

criterion contributed to the creation of Cistricts for both the

House or Delegat,es and the Senate which ope=ate to disadvantage

minority voters in the poJ-itical proeess. The evidence shows

that when prot,ectj,on of incumbents is not a prirnary factor, i"

is possible to create districts without diluting mj-nority voting

streng-,-h anC thus without making it more difficult for minority

voters to elect candidates of their choice through which to

enaet legislation on their behalf. The singJ-e-member Cis:rict,

House plan offered in evidence by the Elam plaintiffs shows the

exrent, to which minority participation is frustrated by the

-39-

opera--ion of th:s c:ite=lon "protect,lon of inc',.unbents. "

This =aci.aI classif:.cat,ion is invaliC uniess it !s the

least Crastic means regui=ei tc achieve a ccurpelllng s:ate

int,erest.. See, Hunter v. Srickson, 393 U.S. at 391-93; Seatt,le

SchooL Dist,. No. 1. 1'. Sta'-e of Wash., 533 f .2C. at 1344.

Deiendants have iailed +-o and cannc+- ai,vance any cornpelling state

j-nte=es', se=.,red by the protect.ion of incumceDts.

The state interest, served, by this criter:.on is desc:ibed

by d,ef endants ' w:.tnes s Robert J . Austin :

Nlzguist,

"llaint,aining exist,ing Cis--ricts does help to

provide legislative contj-nuity. It means

that eveta, ten 1tears you do not have a hun-

Cred new legisla',ols; --hat lzou maiatain the

experience and the general n-ix within the

J-egislature, and reCistricting does not

become a complete turnover."y/

Under the standard,s of Hunter v. Eriekson and i,ee v.

this st,ate interest mus'- iall to the ca=amount sta''€

interes-, in a constitu'-ional =edistricting plan. These standarCs

were properly apPlied b1' the Seat-,le School Dist. Court which

eonsidered d,efendantsr asserti.on that the chal.lengeC statute was

supported by a state interes'- in mandating a state-wide poliey

of neigrhborhood schools. This stat.e int,erest was carefully

scrutlnized by --he Cou,rt and was found not to be compelilng when

compared. to ',he interest of local representative bocies and their

constj-tuencies in the political process. 533 P.2d at 1346. In

so finding, the Court cited Lee v. II$II*, a case in whicb

majoritarian political processes were used to frustrate minority

part,icipation, in whj.ch the three-judge panel held.:

"The . Legislature has aeted to make it more

d.ifficulc for racial minorities to achieve qoals

that, are in their interest.

The statute thus operates to disadvantage

a minority, a racial minority, in the political

process. There can be no sufficient justification."

supporting the necessity of such a course of action.

318 F.Supp. at 710-20.

L7/ Austin dep. , F. 42.

rt

-4 0-

The state's interest in a Cons'-i'-ut,ional =ei.istricting

pIan a plan which is noi maLapportioned anC wh:,ch does :lot

unnecessariJ-y dilute mincrj-ty voting st=ength is '-he paranount

consti'-utional anC State interest to whlch defend,an+-s t criteri.on

of pro--ect,ing incr:mbents raust fall. The EIam pla:.ntiffs' plan

g=aphicai-Iy proves that this paramcunt interest is achieveC by

its single-member Cistricts Crawn without :egari, to protect:.ng

incr:mbents. Thus, the criterion of prot,ect,ing j,ncr:mbents is

txrconstitutional as a violation of the egual protection clause

of the Forst,eenth Amendment.

a

-11,-

i:I. TITE EOUSE AND SE}'iAEE PL{NS AEE

UNCONSTITUTION}.i, FOP. DILUTiON OF BI,,ACK

VOT=NG STRENGEH.

The Pourteenth Amendmen'- proh:.bits 1egi.s1at,:.ve reCis-

t,ricting wh:.ch Ciiutes black voting st,reng'-h and denies bLack

vo--e=s ihe oppor'-unity tc eLect canCidates of. their choice to

the st,ate iegisJ.ature. See Connor v. Finch, ayg., 431 U.S.

ai 122 anc cases citeC. Black voting st=eng:h is CiIuteC,

minj-mized, and cancelLed out when hearry bl-ack popuJ.at.lon ccncen-

trations are u:nnecessarillz fragrmented ani CisperseC, and, when

black population coneentrations a=e jo:.neC with hearry white

population concentrations t,o deny black voters the opport'::nity

to elect cancid,ates o f their chcice . See Connor v . Finch , !!EE,

431 U.S. at 42!-25; Li;p*. v. BoarC of Supe:rrisors of ilinds

Countv, I'tississipoi, 554 F.2d 139, 149 (5ttr Cir.) (en banc),

eert d.enied , 434 U.S. 958 (L977) ; Robinson v. Cornnrissioners Court,

Anderson Counitz, Texas, 505 f .2C 574, 619 (sth Cir. L974); !'locre

v. Leflore Cor::rty Board of Election Conun'rs, 502 F.2C 62!, 622-24

(5tfr Ci=. L974)i gliqe v. Basgett,241 f'. SuPP.96, 109 (!{.D. A].a.

1955) . llulti-member d,istrists, aJ-though not unconst,itutional

per S€ r are unconstitutional when they sr:bmerge black population

ccncent=ations :.n white voting majorities and deny black voters

egual access to the political Process. White v. nggS5ter, 4L2

u.s. 735, 93 S.Ct. 2332, 37 L.Ed.2d 314 (1973) .

Districting schemes are unconstitutional under the

For:rt,eenth Amendnen',- when "conceived or operated as a purposefuL

device to further racj.al discriminat,ion." City of Mobile v.

Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 66, 100 S.Ct. 1490, 64 L.Ed.2d 47 (1980)

(plurality opinion). To prevail, plaintiffs need not prove

that a racial purpose was the so1e, dominant, or even the

prima=y purpose for adopting or maintaining a d,iscriminatoql

scheme, but only that it has been a mot,ivat,ing f actor in the

decision. Village of Arlinqton Heiqh',s v. I"letropolitan Housinq

-12-

@'.,429U.S.232,255-66,97S.Cc.555,50L.Ed.2c450

(197i) . Plaintlffs neeC not prove overt, =acial. s--aEements or

admissions of C:sc=rminatlon, alinough such s'-at,ements are

proved in this record. "Proof oi discriminatory int,ent must,

necessa=i11, re11z on objective factorsr" Personnel Adm'r of

Massachusetts v. $s., 442 U. S. 256 , 277 , 99 S. Ct . 2282 , 60

LEC.2d 870 (1979), aaC reguires a "sensitive inguiry int.o such

circumscarriial anC direc-. evidence of. iD',-€!lt as may be available, "

A=Iinc'ton Eeiqhts, ggpg,, 429 U.S. at 266.

. "!he impact of the official- action--whether it, 'bears

more heavily on one =ace than a!:otherr' Washington v' Pg!g,

1426 U.S. 229, 242, 95 S.Ct,. 2A4A, 48 L.Ed,.2C 5971--may provi.de

an important starting' point. " ltlobile , W., 446 U. S. at 7 0 .

" [A] e-,ions having foreseeabl-e and anticipa'-Ed C.ispa.rate impac-.

are relevant evid.ence to prove '-he ultimate iae'., forbid,den

prupose. " Coh:mbus Bd. of Educ . v. $!gf, 443 U. S . 449 , 464-65 ,

99 S.Ct,. 294L, 61 L.Ed-2d 666 (1979). "The legisLative or

administrative hist,ory may be highJ-y relevant, especialll' where

there are contemporary statements by members of the decision-

maling boCy, minutes of its meetings, or reports." ArLinqton

Heights, 5gg.t 429 U.S. at 268. "The historical background of

--he declsion is one evidentiary source, Pa:iticularly if it

reveals a series of official actions taken for invid.ious

purl>oses." Id. at 267. The a-bsence of a J,egitimate non=acial,

reason for the challenged act,ion is Probative, "particularLy if

the factors usualJ.y considered importa;rt by ',-he decisionmaker

strongly favor a decision contrary to the one reached. ". IC.

Thus, unexplained departures from neutral =edistricting gui,de-

lines support aD inference "that the departures are explicable

only in terns of a purpose to rnininize the voting strength of a

minority group. " Connor v. I$!, !983, 431 U- S - at 425.

In this case, the evidence is strong that t'!re

chailenged districts were crer',-Ed to mj-ninize anC i,iLute black

-4 3-

vo+.ing streng-,h. Each of the challengreC Cj-st=ic--s has a severe

Cj,sc=j:rnina-,-ory impact, anC denies bLack voters the oppo=tunitl,