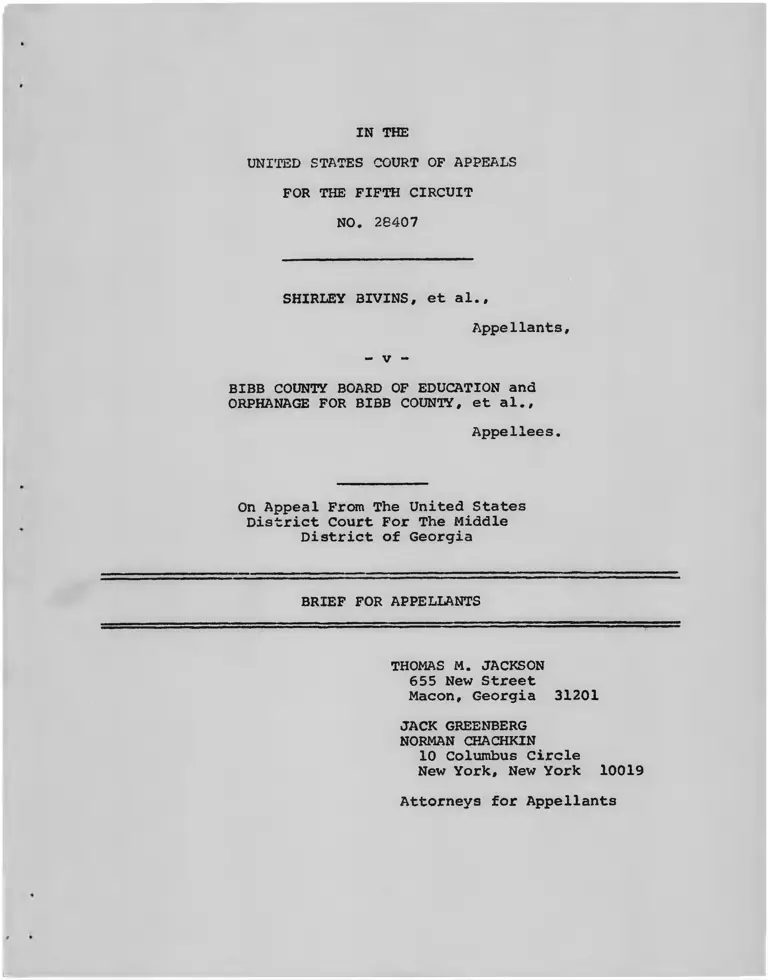

Bivins v. Bibb County Board of Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bivins v. Bibb County Board of Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Brief for Appellants, 1969. 8ae1a0ec-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/615bcc30-c0d6-4a81-88ff-cd381fb2dcd3/bivins-v-bibb-county-board-of-education-and-orphanage-for-bibb-county-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 28407

SHIRLEY BIVINS, et al..

Appellants,

- v -

BIBB COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION and

ORPHANAGE FOR BIBB COUNTY, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States

District Court For The Middle

District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issues Presented for Review • « • • • • • • ........

Statement of the Case • • • • • • • • • • • • • • « ■

Argument

I. The District Court Erred In Approving A

Free Choice Plan For Bibb County Where

Five Years Of Operation Under Free Choice

Had Resulted In But 27% Of The Negro

Students Attending Predominantly White

Schools And Twenty Schools Without A

Single White Student Enrolled ............

II. An Otherwise Ineffective And Unconsitu-

tional Freedom-Of-Choice Plan Is Not

Made Legally Palatable By The Institution

Of Elective Courses Offered Only At Schools Having All Negro Student Bodies . .

III. The District Court Erred In Permitting

The School District To Limit The Opera

tion Of Its Free Choice Plan At Predominantly White Schools By Establishing

A Maximum Number Of Negro Students Who

Are To Be Permitted To Attend Those Schools, Although No Such Limitation

Was Effected At All-Negro Schools ........

Conclusion .........................................

Page

1

2

7

11

14

16*

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir, 1968) • • 10

Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City

County, 382 F.2d 326 (4th Cir. 1967) • • • • • 8

Brica v. Landis, Civ. No. 51805 (N.D. Cal.,

August 8, 1969) . . . . . . .................. i2

Graves v, Walton County Board of Education,

403 F.2d 189 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ................ 10

Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1963).................. 2,3,7.8

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board___ F.2d ___ (5th Cir., May 28, 1969)........ 3

Hilson v. Ouzts, Civ. No. 2449 (M.D. Ga.,

August 8, 1969).............. .. 10

United States v. Board of Education of

Baldwin County, ___ F.2d ___ (5th Cir.,

July 9, 1969) . . . . . ............ . . . . . 4,7,13

United States v. Jefferson County Board

of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (1966),

aff'd on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom.

Caddo Parish School Board v. United

States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967).................. 2,9

- ii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 28407

SHIRLEY BIVINS, et al..

Appellants,

- v -

BIBB COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION and

ORPHANAGE FOR BIBB COUNTY, et al..

Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District Of Georgia

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issues Presented For Review

1. Whether the district court erred in approving a desegrega

tion plan contemplating freedom-of-choice pupil assignment where five

years of operation under free choice had resulted in but 27% of the

Negro students attending predominantly white schools and twenty

schools without a single white student enrolled.

2. Whether an otherwise ineffective and unconstitutional

freedom-of-choice plan i« made legally palatable by the institution

of elective courses offered only at schools having all-Negro student

bodies.

3. Whether the district court erred in permitting the school

district to limit the operation of its free choice plan at pre

dominantly white schools by establishing a maximum number of Negro

students who are to be permitted to attend those schools, although

no such limitation was effected at all-Negro schools.

Statement 0f The Case

This is a school desegregation action.

On April 24, 1964, the Bibb County schools were ordered by

federal district court to desegregate on a gradual basis extending

over several years. This order was subsequently amended June 29,

1967, to require the mandatory exercise of free choice by students

in all grades beginning 1967-68, in accordance with this Court's

opinion in United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (1966), aff'd. on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied sub nonu Caddo Parish School Board v. United

States. 389 U.S. 840 (1967). After the decision in Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County. 391 U.S. 430 (1968) and companion

cases, appellants (plaintiffs below) filed a Motion for Further

Relief which sought to require implementation of a plan other than

freedom of choice. September 16, 1968, the district court issued

an "interim order" requiring appellees to reassess the operation

- 2 -

of the Bibb County schools under free choice in light of Green and

to report their conclusions to the Court, November 29, 1968,

appellees accordingly proposed minor modifications of the plan but

affirmed that freedom of choice was the best ~ and the only —

method of pupil assignment which would create a unitary school

system in Bibb County.

June 4, 1969, appellants filed a second Motion for Further

Relief (A. 1-8) relying upon this Court's decision in Hall v. St,

Helena Parish School Board, ___ F.2d ___ (5th Cir. 1969), again

seeking the district court's disapproval of free choice as a con

stitutional means of operating the Bibb County schools. After a

hearing July 7 and 8, 1969 (A. 106-322) the appellees submitted pro

posed further modifications of their basic free choice plan (A. 29—

37) to which appellants objected (A. 38-52). August 12, 1969, the

district court approved continued free choice in Bibb County (A. 53-

62) and this appeal followed.

The Bibb County Board of Education operates 58 public schools

(A. 25), of which number 20 have enrolled only Negro students (A.

140)• During the five years in which freedom of choice has been

offered to students in the county, no white child has ever exercised

a choice to enroll in one of these 20 schools (ibid.). Through

the same period, Negro enrollment in predominantly white schools has

increased so that about one quarter of the county's Negro students

are attending integrated schools (A. 24, 56). By the district's

- 3 -

own admission —- and giving credence to its claim to increase "free

choice" integration by September 1, 1969 (see A. 56) — over seventy

per cent of the Negro students in the system are still in all-black

schools.

The district sought to continue to assign students according

to a freedom-of-choice plan, but proposed to ameliorate it position

by instituting two elective courses, driver education (A. 172) and

prevocational training (A. 270) which would be offered only at

schools with all-Negro enrollments. Thus white students desiring

to take these courses would have to enter these all-Negro schools

for one or more school periods to receive instruction. By this

feature, and by promising to increase faculty integration to the

minimum levels required by this Court in United States v. Baldwin

County Board of Education. ___ F.2d ___ (5th Cir. 1969), the district

declared, it would achieve the goal of a unitary system without

1/"black" schools and "white" schools, but "just schools."

Little consideration was given to alternative plans of pupil

assignment. Rather, the Board engaged in the circular reasoning

that freedom of choice was the best plan "[o]n the basis that it

1/ However, to prevent "resegregation," the Board proposed to

limit the number of Negro students who could choose to attend

formerly white schools. A motion addressed to this Court, seeking

an injunction pending appeal against this "quota" provision was

denied September 24, 1969.

- 4 -

gives every individual an opportunity to select their own schools

through freedom of choice and it is not discriminatory — " (A. 122-

23). The district did not consider new feeder patterns (A. 132-33)

or make any determined effort to develop any alternative to free

choice (A. 137, 145, 213). Although its administrators opined

that attendance zoning would not be feasible because of segregated

residential patterns (A. 161-62, 262), they had never really tried

to put actual zone lines on a map and evaluate the results (A. 284-

85). It was admitted that pairing of school facilities was feasible

(A. 180-81) but the district opposed this concept because it feared

white students would change their residences causing both paired

schools to become all-Negro (A, 187).

At the hearing, prior to the submission of the district's pro

posed amendments to its plan, the district court expressed its

desire to maintain free choice:

Let me say this. It looks like under

the Green case the racial identiflability

of these schools must be disestablished. I

take it that is what you are trying to do.

I take it that is why you are putting in your

education courses, . . . Evidently you

realize that this must be done, and evidently

you realize that there must be an invasion of

these erstwhile Negro schools by White teachers

and vice versa.

There are certain alternatives that we

may have to face, and those alternatives might

be all this zoning that you don’t want. It

might be this pairing that you don't want. • . .

I'm not particularly anxious for it myself.

It may just possibly be that this is one

5

system where freedom of choice can work if,

as X tried to tell you in my interim order,

you want to make it work.

I think that the freedom of choice

comports with the American dream much more

beautifully than drawing lines and grouping

people and herding them as if they were

cattle, irrespective of their wills and their choices and irrespective of the wills

and choices of their parents. I think freedom

of choice is worth saving if we can save it.

. . . And there is another thing . . . And I

think Judge Parker of the Fourth Circuit was

right, eternally right, when he said that the

Brown decision did not say and was not intended

to say that the people must bring about integra

tion, meaning by that mixing for mixing's sake.

It didn't say that.

Now for these reasons I'm willing to help

the Bibb Board of Education try to save freedom

of choice, because I don't think it works an

imposition on anybody, if the Board of Education

wants to save it, and wants to do and commit

itself to do everything within its power to dis

establish the racial identifiability of all of

the schools of this country.

(A. 292-307).

The district court’s order approving the plan as amended was

entered August 12, 1969 (A. 53-61) and Notice of Appeal filed

August 22, 1969 (A. 321).

6 -

Argument

I.

The District court Erred In Approving A Free

Choice Plan For Bibb County Where Five Years

Of Operation Under Free Choice Had Resulted

In But 27% Of The Negro Students Attending

Predominantly White Schools And Twenty Schools

Without A Single White Student Enrolled.

The district court erred in approving a desegregation plan

using freedom of choice in Bibb County because in five years,

freedom of choice has completely failed to meet the mandate of the

Constitution. It is relevant, as held in Green v. County School

Board of New Kent County, Virginia, 391 U„S. 430 (1968), that many

years elapsed before appellees made any attempt to comply with the

Brown decision. Free choice became the vehicle of compliance but

little progress towards desegregation has taken place. The same

considerations which led the Court in Green to condemn freedom of

choice require the same result here.

Free choice has accomplished little in Bibb County except to

open the doors of white schools to black students. But this Court

said in United States v. Board of Education of Baldwin County, ___

F.2d ___ (5th Cir. 1969):

The indispensable element of any desegrega

tion plan, the element that makes it work,

is the school board's recognition of its

affirmative duty to disestablish the dual

system and all its effects. That duty is

not discharged simply by opening the doors

of white schools to Negro applicants. The,

school from which the Negroes come must be

- 7 -

desegregated as well as the schools to which

they go. And in any situation the school

board should choose the alternative that

promotes disestablishment of the dual system

and eradication of the effects of past

segregated schooling. (Emphasis added)

We urge that, as stated in Green and other cases, freedom of

choice is not an end in itself. Judge Sobeloff in Bowman v. County

School Board. 382 F.2d 326 (4th Cir. 1967), stated:

Freedom of choice is not a sacred talisman;

it is only a means to a constitutionally

required end . . . the abolition of the

system of segregation and its effects. If

the means prove effective, it is acceptable,

but if it fails to undo segregation, other

means must be used to achieve this end. The

school officials have the continuing duty to

take whatever action may be necessary to

create a unitary, non-racial system.

The appellees and the district court tend to view the law in

a different light based upon their determination and desire to

retain freedom of choice. That it has produced very little pro

gress towards the institution of a unitary school system in Bibb

County seemingly has no effect upon their thinking. Freedom of

choice is taken to be the ultimate and only plan capable of working

in the county, even though the Board has not even considered

alternative steps that may prove to be better suited. Again we

quote the Court in Green (391 U.S. at 441):

Where it offers real promise of aiding a

desegregation program to effectuate con

version of a state—imposed dual system to

a unitary, non-racial system there might

be no objection to allowing such a device

- 8

[free choice] to prove itself in operation.

On the other hand, if there are reasonably

available ether ways, such for illustration

as zoning, promising speedier and more

effective conversion to a unitary, non-

racial system, "freedom of choice" must be

held unacceptable.

Free choice has had five years in which to accomplish the

ultimate goal in school desegregation — a unitary system having

not "white schools," and "Negro schools," but just schools. Yet

after five years only 27% of all Negro students are in predominantly

white schools and no white students are enrolled in twenty all-

Negro schools. This is not the result that this Court has required

of desegregation plans chosen by school boards.

The appellees are nonetheless committed to continued use of

free choice. They have not considered alternative plans or methods

such as zoning, pairing or consolidation. During the course of

the hearing on July 7 and 8, 1969, it was admitted that no serious

thought has been given to any plan other than freedom of choice

(A. 122, 137, 138, 144, 145). No reason was given except to say

that it was felt free choice was the best possible plan. When asked

upon what basis this conclusion was derived, Mr. Julius Gholson,

Superintendent of Bibb County Schools, stated simply, "it gives

every individual an opportunity to select their own school through

freedom of choice." This type of reasoning has no validity because

as the Court stated in Jefferson I, 372 F.2d at 888: "A school-

child has no inalienable right to choose his school."

- 9

Appellees contend free choice has achieved and is achieving

desegregation (A. 122), but in light of the fact that only 27% of

all-Negro students are enrolled in white schools and no white

students are in black schools, one finds it hard to accept this

conclusion. To the contrary, the results indicate the failure

of the method; the district court should have followed the rule

established in Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968):

If in a school district there are still all-

Negro schools or only a small fraction of

Negroes enrolled in white schools or no sub

stantial integration of faculties and school

activities then as a matter of law, the

existing plan fails to meet the constitutional

standards as established in Green.

(Emphasis added)

In Graves v. Walton County Board of Education. 403 F.2d 189 (5th

Cir. 1968), this Court reaffirmed its ruling and added:

All-Negro schools in this circuit are put

on notice that they must be integrated or

abandoned by the commencement of the next

school year.

In its opinion (A. 61) the district court refers approvingly

to its opinion in Hilson v„ Ouzts, Civ. No. 2449 (M.D. Ga.,

2/August 8, 1969) in support of the Court's approval of free

choice. In Hilson the district court made clear it» adherence

to the long discarded Briggs dictum:

The segregation outlawed by Brown was

enforced segregation based on race . . .

2/ On appeal to this Court, No. 28491.

10

and not segregation or separateness

voluntarily chosen and preferred by the

persons involved, [slip opinion at p. 5].

The law on the subject is clearly enunciated and free choice

as operated in Bibb County does not meet the law's requirements.

The district court by its own admission favors freedom of choice

(A. 292-307). It flouts the law by aiding the appellees in

retaining an unconstitutional device.

II

An Otherwise Ineffective And Unconstitutional

Freedom-Of-Choice Plan Is Not Made Legally

Palatable By The Institution Of Elective

Courses Offered Only At Schools Having All

Negro Student Bodies.

The attempt by appellees to salvage free choice by the

institution of elective courses in Negro schools (A. 30) is nothing

more than another delaying tactic. There is nothing in the pro

posals that gives the slightest indication that this plan has the

remotest possibility of working. Quite to the contrary# if past

experiences are an indication of success in conducting programs

in Negro schools, these steps are doomed to failure from the outset.

An example in point is the Headstart Program conducted by

appellees. When this program was started about four years ago,

there were centers in both Negro and white schools. Few, if any,

white students enrolled in the centers that were located in Negro

schools. This resulted in centers racially identifiable as Negro

11

centers and white centers. The Office of Economic Opportunity

recognizing this pattern and results, ordered all of the centers

to be located in schools that were racially identified as white

schools, as an attempt to encourage white parents to enroll their

children in the program (A. 113, 241-244). Appellees are aware

of these facts; yet they advance a similar proposal as a means

of attracting white students to Negro schools. Like Headstart,

the courses are elective, which in itself gives rise to a strong

probability that few if any white students will enroll. Previous

experiences have produced failure and appellants contend that

similar results will be encountered in this instance.

The plan is further illusory because the racial identification

of the Negro schools will remain intact. The plan calls for the

white students, if any choose to enroll, to be bussed to Negro

schools for a specific course and, upon completion of the hour of

study, bussed back to the school from which they came. Such a

step places the burden of desegregation entirely upon one racial

group. Cf. Brice v. Landis, Civ. No. 51805 (N.D. Cal., August 8,

1969). The white student does not become a member of the student

body at the Negro school and to say he does is to say one becomes

a member of a family because he visits in that family's home on

occasion. Surely the district court is not so naive as to believe

that Appling High or Ballard-Hudson High will loose their racial

identification as black schools by the proposed device.

12 -

Appellants submit that appellees realize the futility of

this proposal, but because of language in United States v. Board

of Education of Baldwin County, supra, the district court feels

the step is sufficient to comply with what it considers as the

mandate of this Court. Although this Court said in Baldwin

County,

Steps which maybe taken by the Board to

eliminate racial identification of the

present all-Negro schools, in addition to

the specific requirements of faculty

integration, are the establishment of

vocational or other special courses of instruction, summer schools and desegrega

tion of staff and transportation and all

types of extracurricular activities and

facilities

this is not all that the Court said. In keeping with its prior

decisions, this Court still made it clear that freedom of choice

is not the desired end and that a school board should choose the

plan that will work. Contrary to the belief of the district

court that Baldwin County is a carte blanche approval of free

choice as long as there are desegregated vocational and other

special programs, the decision did not establish such a rule.

The prerequisite of the entire opinion is the finding that due

to residential segregation and the location of schools, a

rational pairing or zoning plan which would convert to a unitary

system could not be devised in Baldwin County. Further, the pane],

was very careful to point out that another look at the district,

especially with the aid of HEW, may produce a pairing or zoning

plan that will be preferable tc continued free choice.

13

Freedom of choice has failed and the institution of elective

courses at black schools does not cure the constitutional defect,

III

The District Court Erred In Permitting The

School District To Limit The Operation Of

Its Free Choice Plan At Predominantly white

Schools By Establishing A Maximum Number Of

Negro Students Who Are To Be Permitted To

Attend Those Schools, Although No Such Limitation Was Effected At All-Negro Schools,

The district court erred in imposing a quota system on the

predominantly white schools in Bibb County, That the Court had

to do so dramatically points up the failure of free choice as a

workable device of dismanteling the dual system. To the contrary,

rather than dismantling the dual system, free choice facilitates

its continued existence. As Negro children enroll in white schools

white students exercise their choice and move out. Such was the

case in the four schools upon which the district court originally

placed the quota. In these schools there was a sharp decrease in

the number of white students who chose them in 1968 as opposed to

the number who chose them in 1969 (A, 2-3),

Imposing a quota whereby no more than 40% of a white school's

student body may be black will not prevent the mass exodus of

white students from these schools and thereby prevent resegrega

tion, because there is no corresponding restriction upon the

Negro schools. If indeed resegregation is to be prevented by

14

such a method, there should be a 60-40 ratio imposed on all

schools. Since this is not the case, what it amounts to is that

Negro students are restricted in their "choice" of schools,

unless they are lucky enough to be in the 40% that is first to

pick a certain school. The only real choice belongs to the white

students. Such an arrangement is grossly inequitable and further

points up the shortcomings of free choice.

Such a system imposes an additional burden on the Negro

parents and students who choose integrated schools that have

reached the 40% level. They are confronted with choosing another

school that has not reached the 40% level, which is almost of

necessity located quit& a distance from their neighborhood; or,

they must go to the all-Negro school that is nearest them. Such

was the experience with students in the four schools now operating

under the quota system. A total of 611 students were displaced

(A. 63) by this device.

Under this system, there is an even greater possibility of

failure, in that if all of the white schools reach the 40% level,

there will be no choice for black students at all. They must

attend the all-Negro schools that the system will continue to

maintain; the situation will be the same as it was before any

steps were taken towards desegregation. Thus the quota system

has the effect of re-enforcing the pattern of all-black schools

rather than eliminating them.

- 15

CONCLUSION

Appellants respectfully submit that the order of the district

court be vacated and the case remanded with directions that the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare be requested to

formulate a comprehensive plan of desegregation for immediate

implementation in the Bibb County School System.

Respectfully submitted.

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

16