Legal Research on Session Laws - 1981, Chapter 800

Unannotated Secondary Research

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Legal Research on Session Laws - 1981, Chapter 800, 1981. 82cb7e6f-d392-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/616df18a-7a65-42ad-8322-478b2bc99a8d/legal-research-on-session-laws-1981-chapter-800. Accessed February 02, 2026.

Copied!

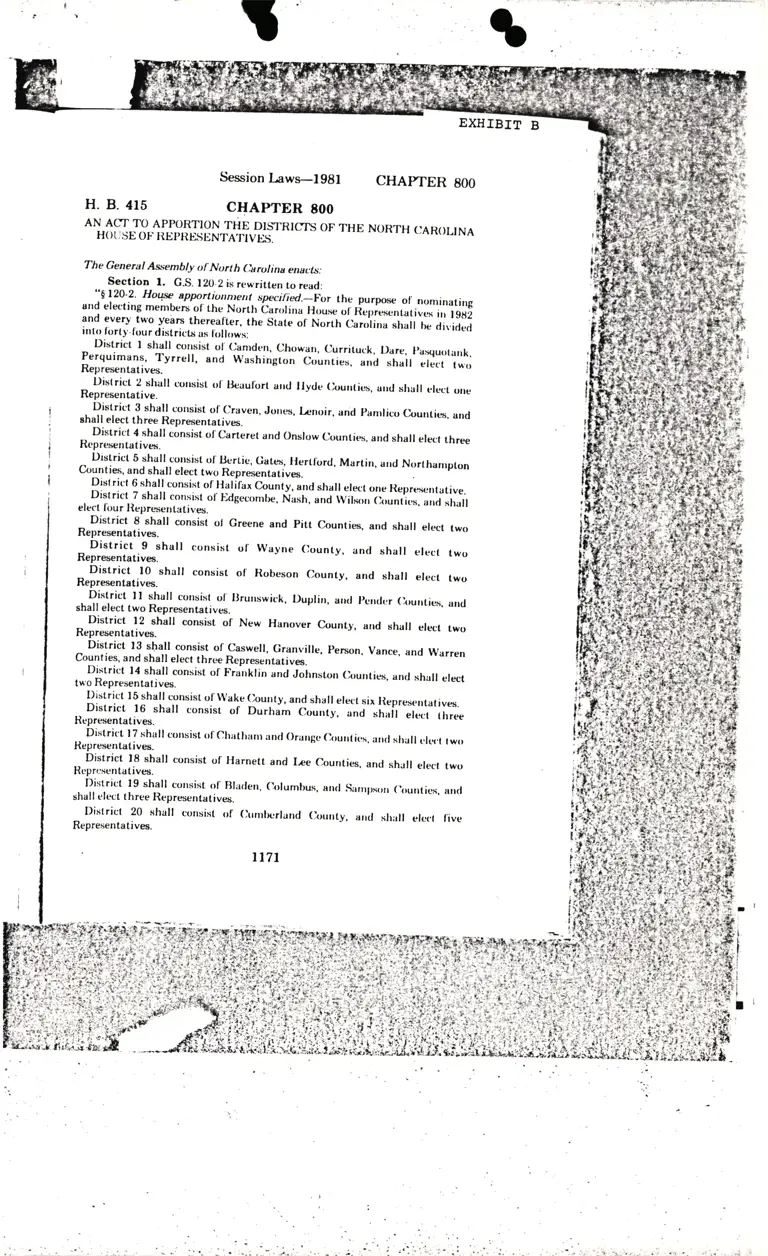

AN ACT TO APPORTION THE DISI'RICTS OF THE NORTH CAR,LINAH0 I J SE OT' REPTiESI,NTA'I'I VES.

The General Axsembly of Norlh (iarolina enacls:

Section f. C.S. 120-2 is rewritten to read:

"$ 120-2' Hoqe app.rtltn1ynt specirid.-For the purpose o' n.nrinatirrgand electing memben ol the North i-'arolina Hiruse ol'Represcntatives i' I9,2and every two yeirrs therearrer, the state of North carorina shalr lrc di'idedinto lbrt1,-lirur districts us lirllows:

H. B. 4r5

District lI shull consist ol'

shall elect two Representatives.

District 12 shall consist of

Representatives.

EXHIBTT B

lbssion Laws-lg8l CHApTER g00

CHAPTER 8OO

l'axluolarrk.

elect two

llrunswick, Duplirr, arxl l)errrler (irurrtics. urrr.l

' New Hanover County, and rhall elect two

I l7l

District I shall consist of (_lanrden, Chowan, Curituck, l)are,Perquimans, Tyrrell, and Washingtun Currties, arrd shall

Representat ives.

District 2 shall cottsist ol lleaulbrt urrd llyde (iourrtics, urrd slall elect orreRepresentative.

District 3 shall co.sist ,r'c'raven, Jorres, Lenoir, and panrric, ()rurrti,', undehall elect three Representatives.

District 4 shall consist of c'arteret and onsr.w countits, and shail erect threeRepresen tative,n.

District 5 shull colrsist o[ B_ertie, Gate$, Hertrbrd, Martirr, arrd NortlrarrrptonCounties, and shall etect twcr Representativrs.

Dist rict 6 shall c,nsist of Halifax county, and srrail erect ,ne Represerrtutive.District 7 shall consist ot lirtgecombe, f.r"rf,, rra lVilxr, O,unties. arr, shallelect lirur liepresentatives.

District 8 shall consist or Greene and pitt counties, and shail erect twoRepresentatives,

District 9 shar t consist ,t' wayne o,unty, and shart erect tw,Representatives.

District l0 shail consist of R,beson county, and shail erect tw,Representativm.

tl-r',

*iJi

ii:a ,i!

arYc'2.-

lr-d'

- District 13 shall consist of caswer, Granvile, person. vance, and warrenCounties, and shall etect thre.e Representatives.

District l4 shall consist o[ Frarrkrin and Jorrnst., (irulrties, and shail ete.ttn'o Representatives.

District l5 shall c,nsist ,l \vak-e c.urrty, and shalr erect six ltepreserrtatives.District l6 sharr consist of Durhim c.urty, and shall erect lrrreeRepresentatives.

District l7 sharr consist o[ctratrranr anrr orarrge orurrtics, arrrt shup t,lei.r rw,Representati ves.

District 18 shail consist.f Harnett and Lee counties, and shart erecr two

Reprr,'selr tatives.

f)istrict l9 shall corrsist rI Brarten, (-irtumbus, anrr Sanrps,rr (irurrties, arrrr

shall elect three Representatives.

Districl 20 shall consist ,f (rrnrrrcrra,d o'urrty, alrd srrail erect t.ive

Representati ves.

f!

t

t

I

CHAPTER 8OO Session Laws-l9gI

tt"i;#[l,lshall qr'sist .f H.ke and scottand counries, and shall etect one

-, *o,Ti'J:t"'"i*:l[r:xt,l' A I a mance a n d R'ck i ngham c-oun ries, and shat I

o"3*J,Ilr,'"Lshall c,nsist ,l' Guiltord county, and shau erect seven

District 24 shal

Representatives. -'l co,sist ol' Randolph county, and shall elect two

District 25 sha' *rrrsist.f-Mqrre c'.unty, and sha, erect one Repreentative.

,,,,1t1;'."LTrshall.r'onsist

tr n'-"'i"a fiui.',*ur,"., c,u,tiet, and sha, erect

n"SrXJi::r,1.

shall c.nsist or Richmrnd courrty, and shau ere* one

Distrir.t 2tJ shull t

t :u-,,, t i "",,,t ..iji ;,

"""

il#il1','*:.,Jl; *1"'

s I okes, surry, an d wa tauga

""1*'.t"Xilr,ig

.shall "un'i'i-i:ii';"il"county, and shau erect five

,r.?:ffiii:;;l,r,lo;,,,_,rt ,t.t)avids,, and Davie C,unties, and sha, etect

^""r.'"Ui;ir,jl.

shatt co'sist o[ Rowan c.unty, and shail erecr two

District J2 shall *1:_rl

:, S.r:nly (irunty, and sha,

_elect ,ne Representative.

,,,3:'$j,;i#,illll;:"*''t .f oala rrus' Jni'Lniun counries, and sha, erecr

. l)istrict J4 shall runsist ol.()aldwell, Wilkcr.ele-c't three R"p.*.nirt,r*. , and Yadkin Cnunties, and shal

,-3riil}tJr:rt

shall consist ot'Alexander and Iredeil counties, and shal erect

"""*:*,if;hall

c,rrsist ol' Mecklenburg cburrry, and shall elect nine

l ) ist rir.t iJ7 s ha llH"p.*"r,irtir;.""'" ttrrtstst ol' catawba c,unty, and shall elect two

^"'JJ:[i:l,1shall

c,,sist ,l'Gaston and Lincot, counties, and sha[ etect four

","3'i:1'jr,j,l,:l.:,ilJ;ilHt

o[ Aver.v, Burke, and Mitcheu counties, and shau

-,,auill :Ii" l,?J]',iiil,::.i,.:,il

of crever a, d, por k, a n d R u t herford cou n t ies, a nd

,,,,X,1'i;l';:..1i;lli'J. ""'''-' ,l' McD,well arrd yancey orunries, and shal erect

District 42 shall cons

u.tres, a,d str., ctect ,r",jfjl,^r.:.1:.:*:, Henderson, and Transytvania

",,1111::,.,1.{

*r,,,tr "roJi.iuJ;d';;ii;:ilX

ifi:1[,::,1T1' ;H::'":l#,yil;;; J;.4;,, M a d i so n, a n d s wa i n cou n t i es,and shall elect lwo Rtpresentativ*-

?J,',',',1, :.1 :llX' LUn: f,*ji,,okee,

ct av, G ra ha nr, a nd M acon coun ries,arrd slrall elect one Rtprcsentative..,

Sec. 2. This ;r.t is cl1i.<.t ivc u;xxr ral i[it.rrtion.

,r,r, Tllll

('le,eral Arsernblv t"ra ilr"r tl-os and ratiried, this the Jrd day of

H.

AI\

I

(

'l'h

t{

|-t.

Ioll

nal

b.v

obl

"r?

ban

li,rl,

eirl

puh

recl

nat

Jul

H.

AN

t

t

'I',ht

bv(

arld,

crea

dele

rcad

.,!

t 984

3sh

nlen

in l1

read

"t

C'our

coml

but I

tt72