Ruling on Propriety of Considering a Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish Desegregation of Detroit Public Schools

Public Court Documents

March 24, 1972

5 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Ruling on Propriety of Considering a Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish Desegregation of Detroit Public Schools, 1972. 8303d712-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/61de311a-e034-4be9-a889-46a51a209930/ruling-on-propriety-of-considering-a-metropolitan-remedy-to-accomplish-desegregation-of-detroit-public-schools. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

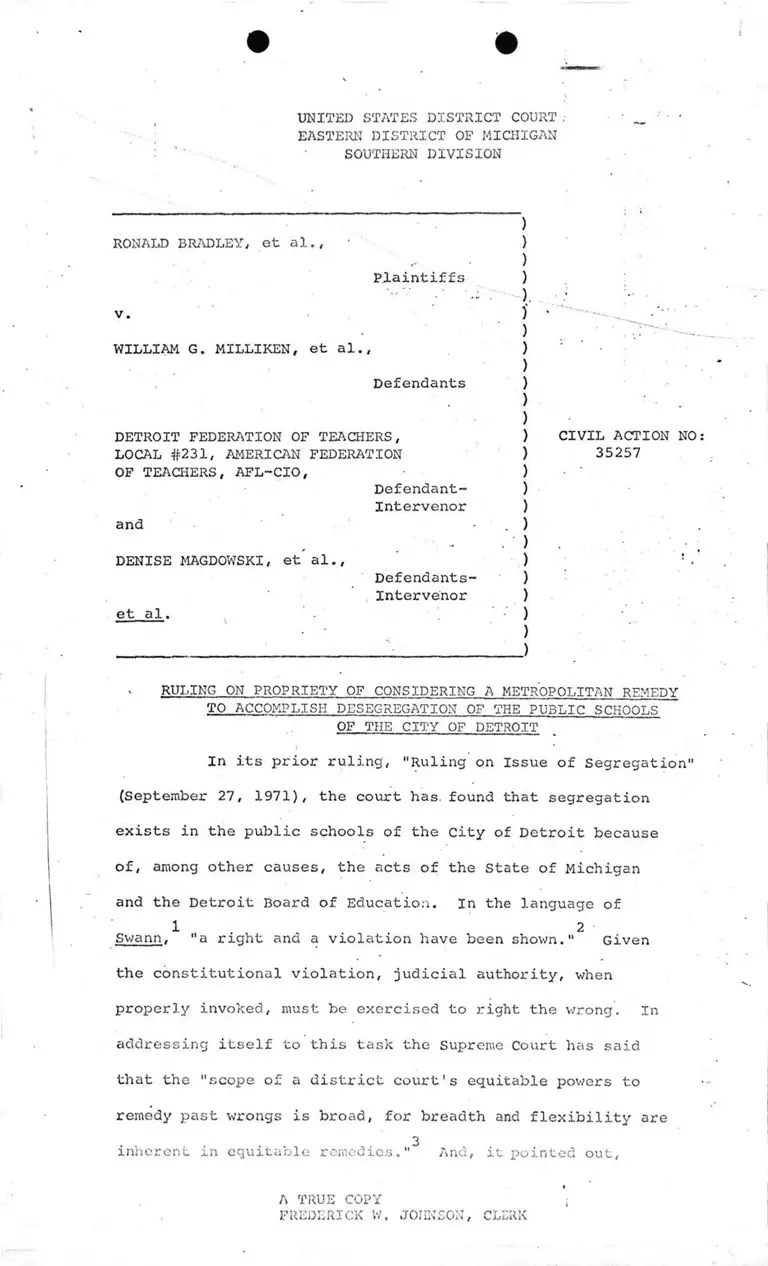

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT ;

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

' SOUTHERN DIVISION

)

RONALD BRADLEY, et aL, ' }

, • )

Plaintiffs )

■ •; . ).

v. )

* )

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., )

)

Defendants )

. )

)

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, )

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION )

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, • )

Defendant- )

Intervenor )

and . )

, - )

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al., )

Defendants- )

Intervenor )

et al. . )

.... )

_______________ _____ _ ______ _______ )

' -

CIVIL ACTION NO:

35257

v RULING ON PROPRIETY OF CONSIDERING A METROPOLITAN REMEDY

TO ACCOMPLISH DESEGREGATION OF THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS

. OF THE CITY OF DETROIT

In its prior ruling, "Ruling on Issue of Segregation'1

(September 27, 1971), the court has. found that segregation

exists in the public schools of the City of Detroit because

of, among other causes, the acts of the State of Michigan

and the Detroit Board of Education. In the language of

1 2Swann, "a right and a violation have been shown." Given

the constitutional violation, judicial authority, when

properly invoked, must be exercised to right the wrong. In

addressing itself to this task the Supreme Court has said

that the "scope of a district court's equitable powers to

remedy past wrongs is broad, for breadth and flexibility are

. 3inherent in equitable remedies." And, it pointed out,

A TRUE COPY

FREDERICK W. JOHNSON, CLERK

"a school desegregation case does not differ fundamentally

from other cases involving the framing of equitable remedies to

• , . 4repair the denial of a constitutional right." The task

is to correct the condition which offends the Constitution.

Illustrative of what was meant by the Supreme Court, see

the legislative and congressional reapportionment cases.5

Under the circumstances of this case, the question

presented is whether the court may consider relief in the

form of a metropolitan plan, encompassing not only the city

of Detroit, but the larger Detroit metropolitan area which,

for the present purposes,- we may define as comprising the

three counties of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb. It should be

noted that the court has just concluded its hearing on plans

^submitted by the plaintiffs and the -Detroit Board of Education

for the intra-city desegregation of the Detroit public schools.

A ruling has not yet been made on these plans, but in■ s ■ , ,

accordance with the mandate of the Court of Appeals that a

hearing on the merits be concluded at the earliest possible

time, we consider it necessary to proceed apace with a

resolution of the issue before us, i_.js., the propriety of

weighing the legal availability of a metropolitan remedy for

segregation. . . '

The State defendants in this case take the position,

as we understand it, that no "state action" has had a part

in the segregation found to exist. This assertion disregards

the findings already made by this court, and the decision of

7the Court of Appeals as well. Additionally, they appear to

view the delegation of the State's powers and duties with

respect to education to local governmental bodies as vesting

the latter with sovereign powers which may not be disturbed

by either the State or the court. This we cannot accept. ...

Political subdivisions of the states have never been

considered sovereign entities, rather "they have been

traditionally regarded as subordinate governmental instru

mentalities created by the state to assist it in carrying

out of state governmental functions." Reynolds v. Sims, •

377 U.S. 533, 575. perhaps the clearest refutation of the

State's asserted lack of power to act in the field of education

is Act 48 of 1970. The State cannot evade its constitutional .

responsibility by a delegation of powers to local units of

government. The State defendants' position is in error in two

other respects: 1. The local school districts are not

fully autonomous bodies, for to the extent it has seen fit the

State retains control and supervision; and 2. It assumes that

any metropolitan plan, if one is adopted, would, of necessity,

require the dismantling of school districts included in the

plan. . . •

The main thrust of the objections to the consideration

of a metropolitan remedy advanced by intervening school

districts is that, absent a finding of acts of segregation on

their part, individually, they may not be considered in

fashioning a remedy for relief of the plaintiffs. It must

be conceded that the Supreme Court has not yet ruled directly

on this issue? accordingly, we can only proceed by feeling

our way through its past decisions with respect to the goal

to be achieved in school desegregation cases. Green v . County

School Board, 391 U.S. 430, teaches us that it is our

obligation to assess the effectiveness of proposed plans of

desegregation in the light of circumstances present and the

available alternatives; and to choose the alternative or

alternatives which promise realistically to work now and

hereafter to produce the maximum actual desegregation. As

Chief Justice Burger said in Swann, "in seeking to define

,the scope of remedial power of courts in an area as

sensitive as we deal with here, words are poor instruments

to convey the sense of basic fairness inherent in equity."

Substance, not semantics, must govern. *

• 8It seems to us that Brown xs dispositive of .the

issue:

"In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles.

Traditionally, equity has been characterized by a

practical flexibility in shaping its remedies and by

a facility for adjusting and reconciling public and

- private needs. These cases call for the exercise of

these traditional attributes of equity power. At

stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs in

admission to public schools as soon as practicable on

a nondiscriminatory basis. To effectuate this interest

may call for.elimination of a variety of obstacles in

making the transition to school systems operated in

accordance with the constitutional principles set forth

in our May 17, 1954, decision. Courts of equity may

properly take into account the public interest in the

elimination of such obstacles in a systematic and

effective manner. But it should go without saying that

the vitality of these constitutional principles cannot

be allowed to yield simply because of disagreement with

them." •

* * * •

" * * * the courts may consider problems related to

administration, arising from the physical condition of

the school plant, the school transportation systems,

* personnel, revision of school districts and attendance

areas into compact units to achieve a system of

determining admission to the public schools on a

nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and

regulations which may be necessary in solving the

foregoing problems."

We conclude that it is proper for the court to

consider metropolitan plans directed toward the desegregation

of the Detroit public schools as an alternative to the

present intra-city desegregation plans before it and, in the

event that the court finds such intra-city plans inadequate

- 4 ™

i

to desegregate such schools, the court is of the opinion that

it is required to consider a metropolitan remedy for

desegregation.

The schedule previously established for the hearing

on metropolitan plans will go forward as noticed, beginning

March 28, 1972.

1Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 402 U.S. 1.

2Ibid., p. 15.

3Ibid., p. 15.

4Ibid., pp. 15, 16. .

5 *

Reynolds v. Sims, 377'U.S. 533.

6 ‘See' "Ruling on Issue of Segregation," supra, indicating a

black student projection for the school year 1980-81 of 80.7%.

7

See "Ruling on Issue of Segregation," supra; Bradley v.

Milliken, 433 F.2d 897.

8

Brown v. Bd. of Ed. of Topeka, 34 9 U.S. 2?4, at 300 and 301.

5-

I