Burlington v Dague Sr Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 10, 1992

50 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burlington v Dague Sr Brief Amicus Curiae, 1992. a45d0713-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/62d5bc28-e8de-4563-a62b-ff942860b91e/burlington-v-dague-sr-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

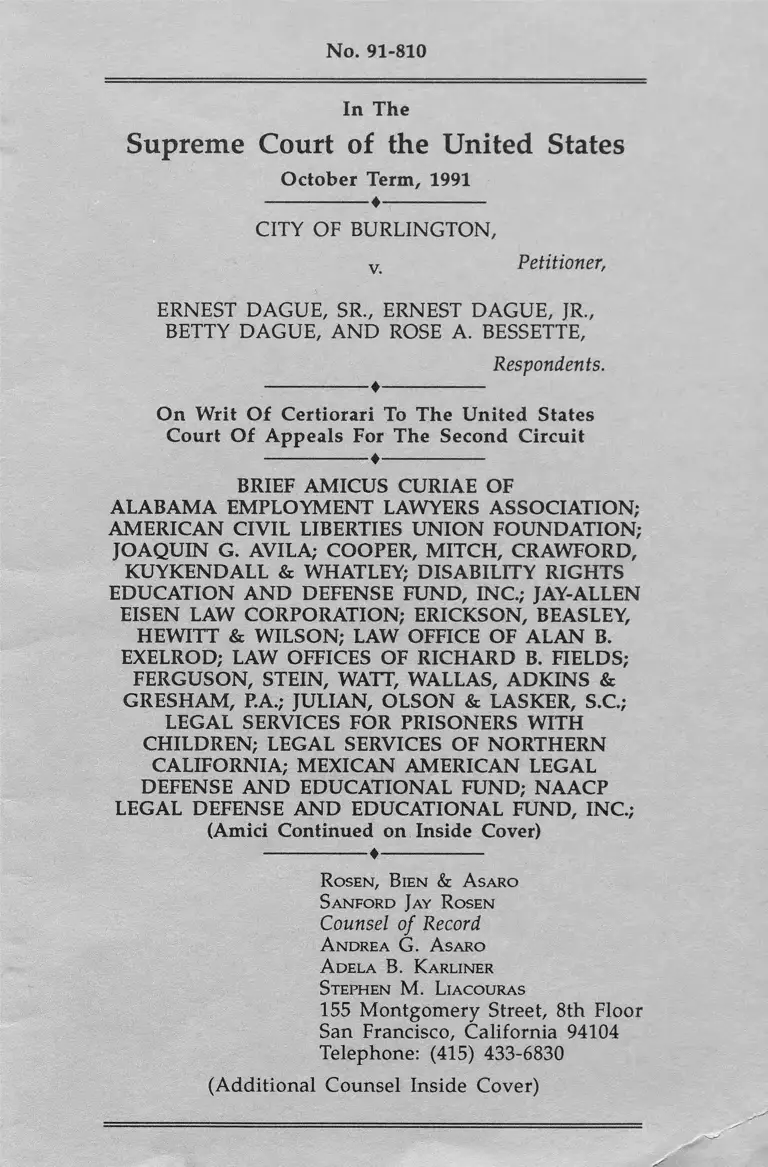

No. 91-810

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1991

-----------------♦-----------------

CITY OF BURLINGTON,

v . Petitioner,

ERNEST DAGUE, SR., ERNEST DAGUE, JR.,

BETTY DAGUE, AND ROSE A. BESSETTE,

♦

Respondents.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States

Court Of Appeals For The Second Circuit

--------------- ♦---------------

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF

ALABAMA EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIATION;

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION;

JOAQUIN G. AVILA; COOPER, MITCH, CRAWFORD,

KUYKENDALL & WHATLEY; DISABILITY RIGHTS

EDUCATION AND DEFENSE FUND, INC.; JAY-ALLEN

EISEN LAW CORPORATION; ERICKSON, BEASLEY,

HEWITT & WILSON; LAW OFFICE OF ALAN B.

EXELROD; LAW OFFICES OF RICHARD B. FIELDS;

FERGUSON, STEIN, WATT, WALLAS, ADKINS &

GRESHAM, P.A.; JULIAN, OLSON & LASKER, S.C.;

LEGAL SERVICES FOR PRISONERS WITH

CHILDREN; LEGAL SERVICES OF NORTHERN

CALIFORNIA; MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND; NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.;

(Amici Continued on Inside Cover)

---------------♦---------------

Rosen, Bien & A saro

Sanford Jay Rosen

Counsel of Record

A ndrea G. A saro

A dela B. Karliner

Stephen M. Liacouras

155 M ontgomery Street, 8th Floor

San Francisco, California 94104

Telephone: (415) 433-6830

(Additional Counsel Inside Cover)

NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIATION;

PATTERSON, HARKAVY, LAWRENCE, VAN NOPPEN

& OKUN; RICHARD M. PEARL; PRISON LAW

OFFICE; PLANNED PARENTHOOD AFFILIATES OF

CALIFORNIA; PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.; PUBLIC ADVOCATES,

INC.; AND ROSEN, BIEN & ASARO

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

--------------- ♦---------------

Steven R. Shapiro

John A. P owell

American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

Leon Friedman

Co-counsel for the American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

148 East 78th Street

New York, NY 10021

(212) 737-0400

Richard Larson

Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

634 South Spring Street, 11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

Julius L. C hambers

C harles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

T erisa E. C haw

National Employment Lawyers Association

535 Pacific Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94133

(415) 397-6335

- 1-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS . ................................................. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................... ii

INTEREST OF AMICI C U R IA E ................................... 1

SUMMARY OF A RG U M EN T...................................... 1

ARGUMENT ................................................................... 3

I. In Enacting Fee-shifting Statutes, Congress has

Mandated that the Amount of Attorney’s Fees

Awarded to Prevailing Plaintiffs be Determined in

Accordance with Relevant Private Markets for

Legal S e rv ic e s .......................................................

II. Application of Market Principles and Practices

Mandates that Prevailing Parties in Actions

Brought Under Fee-shifting Statutes be Awarded

Contingent Risk Enhancers ................................

III. Justice O’Connor’s Approach in Delaware Valley

II is a Fair and Workable Way to Determine

When Risk Enhancement is Necessary to Assure

that the Prevailing Plaintiff is Awarded a

Reasonable Attorney’s Fee in a Fee-Shifting

C a s e .......................... .. ...................... ....................

CONCLUSION ............................... ............................

APPENDIX

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Arens on v. Board o f Trade,

372 F.Supp. 1349 (N.D. 111. 1974) . . . . . . . . . 14

Bemardi v. Yeutter,

951 F.2d 971 (9th Cir. 1 9 9 1 ) ................. .. ........... 20

Blanchard v. Bergeron,

489 U.S. 87 (1 9 8 9 ) ................................................. 6

Blank v. Talley Indus.,

390 F.Supp. 1 (S.D.N.Y. 1 9 7 5 ) .......................... 13

Blum v. Stenson,

465 U.S. 886 (1984) ...................................... 4, 5, 6

Bouman v. Block,

940 F.2d 1211 (9th Cir. 1 9 9 1 ) ............................. 20

Brandon v. Holt,

469 U.S. 464 (1985) .............................................. 5

In re Cenco, Inc. Sec. Litig.,

519 F.Supp. 322 (N.D. 111. 1981) ....................... 14

Chemer v. Transitron Elec. Corp.,

221 F.Supp. 55 (D.Mass. 1963), modified on

other grounds, 326 F.2d 492 (1st Cir.

1964) ....................................................... .. ............... 14

City o f Detroit v. Grinnell Corp.,

495 F.2d 448 (2nd Cir. 1974) ............................. .1 3

-iii-

City o f Riverside v. Rivera,

477 U.S. 561 (1986) .............................................. 6

Conklin v. Lovely,

834 F.2d 543 (6th Cir. 1 9 8 7 ) ................................ 18

In re Coordinated Pretrial Proceedings,

410 F.Supp. 680 (D. Minn. 1 9 7 5 ) ....................... 13

County o f Suffolk v. L1LCO,

710 F.Supp. 1477 (E.D.N.Y. 1989), afffd in

part, rev’d in part on other grounds,

907 F.2d 1296 (2d Cir. 1990)................................ 14

Crawford Fittings Co. v. J. T. Gibbons, Inc.,

482 U.S. 437 (1987) .............................................. 6

Davis v. County o f Los Angeles,

8 EPD 1 9444 (C.D. Cal. 1 9 7 4 ) .......................... 4

D ’Emanuele v. Montgomery Ward & Co. Inc.,

904 F.2d 1379 (9th Cir. 1990) ............................. 21

Dayton Board o f Education v. Brinkman,

443 U.S. 526 (1979) .............................................. 5

Department o f Labor v. Triplett,

494 U.S. 715 (1990) .............................................. 10

Evans v. Je ff D,

475 U.S. 717 (1986) .............................................. 6

Fadhl v. City and County o f San Francisco,

859 F.2d 649 (9th Cir. 1 9 8 8 ) ............ 19, 20

Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts,

467 U.S. 561 (1984) ..................................... 5

In re General Pub. Utils. Sec. Litig.,

[1983-1984 Transfer Binder] Fed. Sec. L.

Rep. (CCH) 199,566 (D. N.J. Nov. 16, 1983) . 14

Green v. Transitron Elec. Corp.,

326 F,2d 492 (1st Cir. 1 9 6 4 ) ................. .. 14

In re Gypsum Cases,

386 F.Supp. 959 (N.D. Cal. 1974), a f f d,

565 F.2d 1123 (9th Cir. 1977) ............................. 13

Hasbrouck v. Texaco, Inc.,

879 F.2d 632 (9th Cir. 1 9 8 9 ) .......................... 5, 20

Hendrickson v. Brendstad,

934 F.2d 158 (8th Cir. 1 9 9 1 ) ................................ 19

Hidle v. Geneva County Bd. ofEduc.,

681 F.Supp. 752 (M.D. Ala. 1 9 8 8 ) .................... 15

Islamic Center o f Miss. v. Starkville,

876 F.2d 465 (5th Cir. 1 9 8 9 ) ................................ 18

Jackson v. Rheem M fg.,

904 F.2d 15 (8th Cir. 1990 )................................... 19

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) .......................... 4, 5

-iv-

Keith v. Volpe,

86 F.R.D. 565 (C.D. Cal. 1980) 14

-V-

King v. Board o f Regents,

748 F.Supp. 686 (E.D. Wis. 1990) .................... 19

Lapina v. Williams,

232 U.S. 78 (1 9 1 4 ) ................................................. 7

Lattimore v. Oman Constr. Co.,

714 F.Supp. 1178 (N.D. Ala. 1989), a ffd ,

868 F.2d 437 (11th Cir. 1 9 8 9 ) .................... 15,21

Leigh v. Eagle,

714 F.Supp. 1465 (N.D. 111. 1989)....................... 19

Leroy v. City o f Houston,

831 F.2d 576 (5th Cir. 1987), cert.

denied, 486 U.S. 1008 (1988)................................ 18

Li nay Bros. Bldrs., Inc. o f Phila. v. American

Radiator & Standard Sanitary Corp.,

487 F.2d 161 (3rd Cir. 1 9 7 3 )................................ 13

McGuire v. Sullivan,

873 F.2d 974 (7th Cir. 1 9 8 9 ) ................................ 19

Merritt v. Mackey,

932 F.2d 1317 (9th Cir. 1991) .............................21

Missouri v. Jenkins,

491 U.S. 274 (1989) ........................................ 5, 6

Morris v. American National Can Corp.,

952 F.2d 200 (8th Cir. 1 9 9 1 ) ................................19

Municipal Auth. o f Bloomsburg v. Pennsylvania,

527 F.Supp. 982 (M.D. Pa. 1 9 8 1 )....................... 14

-VI-

Oviatt v. Pearce,

92 D.A.R. 723, 728 (9th Cir. Jan. 16, 1992) . . 20

Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens’

Council fo r Clean Air,

478 U.S. 546 (1986) ....................... .. ................... 3

Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens’

Council fo r Clean Air,

483 U.S. 711 (1987) ......................................passim

Perlman v. Feldmann,

160 F.Supp 310 (D. Conn. 1958) ....................... 14

Purdy v. Security Sav. and Loan Assoc.,

727 F.Supp. 1266 (E.D. Wis. 1989).................... 15

Richardson v. Alabama State Bd. ofEduc.,

935 F.2d 1240 (11th Cir. 1991) .......................... 21

Rievman v. Burlington N. Ry. Co.,

118 F.R.D. 29 (S.D. N.Y. 1987) .................... .1 5

Skelton v. General Motors Corp.,

860 F.2d 250 (7th Cir. 1988), cert.

denied, 493 U.S. 810 (1989) ................................ 19

Soto v. Adams Elevator Equipment Co.,

941 F.2d 543 (7th Cir. 1 9 9 1 ) ................................ 19

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher,

64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974).............. 4

Steinberg v. Hardy,

93 F.Supp. 873 (D. Conn. 1950).......................... 14

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f

Education,

66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D. N.C. 1 9 7 5 ) ....................... 4

In re Union Carbide,

724 F.Supp. 160, 169 (S.D.N.Y. 1989)............... 16

U.S. v. City and County o f San Francisco,

748 F.Supp. 1416 (N.D. Cal. 1 9 9 0 ).................... 12

United States v. Great N. R. Co.,

287 U.S. 144 (1932) .............................................. 7

Venegas v. Mitchell,

495 U.S. 82 (1 9 9 0 ) ................................................. 6

Wolf v. Planned Property Management,

735 F.Supp. 882 (N.D. 111. 1990) ....................... 19

STATUTES

15 U.S.C. § 13(a) (1988) .............................................. 20

20 U.S.C. §§ 1400-1485 (1988) . ................................ 7

22 U.S.C. § 277d-21 (1988) ..................................... . 8

28 U.S.C. §§ 2412(d)(1)(A) and (2)(A) ( 1 9 8 8 )____ 7

28 U.S.C. § 2678 (1988) .............................................. 8

30 U.S.C. § 901 etseq (1 9 8 8 ) ..................................... 10

33 U.S.C. 1365(d) (1 9 8 8 ) ................. .. ....................... 1 ,3

42 U.S.C. § 300aa-15(b) (1 9 8 8 ) ................................... 8

-vii-

42 U.S.C. §406(b)(l) (1988) ......................................... 8

42 U.S.C. § 1988 (1988) ......................................passim

42 U.S.C. § 6972(e) (1 9 8 8 ).................... .. .............. 1, 3

48 U.S.C. § 1424c(f) (1988) ......................................... 8

50 U.S.C. app. § 1985 (1990) ...................................... 8

OTHER AUTHORITY

Class Action Reports

July-Aug., Sept.-Oct., 1990, 249 ....................... 14

S. Rep. No. 94-1011 (1976)........................................... 4

H.R. 5757, 98th Cong. 2d Sess. (1984)....................... 7

H.R. 3181, 99th Cong. 1st Sess. (1985) .................... 7

Stemlight, The Supreme Court’s Denial o f

Reasonable Attorney’s Fees to Prevailing

Civil Rights Plaintiffs, 17 N.Y.U.

Review of Law & Social Change

535, 537-38 (1990) .......................... .. 12

Terry, Eliminating the Plaintiff’s Attorney in

Equal Employment Litigation: A

Shakespearean Tragedy,

5 Lab. Law. 63 (1 9 8 9 ) ........................................... 12

Model Code of Professional Responsibility

D R -2-106(B ).................... .. ................................... 9

Model Rules of Professional Responsibility, Rule 15 . 9

-viii-

-1-

INTEREST OF AM ICI CURIAE1'

Amici are not-for-profit legal services organizations,

private law firms and sole practitioners from throughout the

United States. The legal services organizations engage in

a wide variety of public interest litigation. They depend on

reasonable attorney’s fees awards, pursuant to fee-shifting

statutes, to finance their litigation. The enhancement of

their attorney’s fees to compensate for the risk of taking

matters on a contingency basis enables them to attract

cooperating counsel from private law firms. Without the

ability to attract private counsel, they would be unable to

obtain representation for many of the prospective clients

who seek their legal assistance.

The private law firm and sole practitioner amici

devote a substantial portion, if not all, of their practices to

public interest litigation under a variety of fee-shifting

statutes. This litigation is virtually always undertaken on

a contingency basis. If contingent risk enhancers were not

available to compensate these private attorneys when they

prevail, economic necessity would force many of them to

turn down meritorious cases in favor of hourly-fee paying

clients.

More detailed Statements of Interest for each amicus

are contained in the Appendix attached to the Brief.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Many public interest statutes, including the Solid

Waste Disposal Act, the Clean Water Act and a host of

others, contain "fee-shifting" provisions that entitle

- Letters of consent to the filing of this Brief have been lodged

with the Clerk of the Court, pursuant to Rule 37.3.

-2-

prevailing plaintiffs to recover their reasonable attorney’s

fees, in addition to whatever other relief they may be

awarded in the course of litigation. The determination that

a "reasonable" attorney’s fees award in a case brought

under a fee-shifting statute includes an enhancement for

contingent risk reflects the recognition by many courts that

legal services, like other services, are priced in accordance

with the principles and practices of the marketplace.

The legislative history of Section 1988 of the Federal

Civil Rights Attorney’s Fee Award Act of 1976 — which

sets the standard for attorney’s fees awards to prevailing

parties in cases brought under federal fee-shifting statutes

— reveals Congress’ intent that the marketplace determine

the amount of a reasonable attorney’s fees award. Market

analysis, in turn, dictates that an attorney who prevails on

behalf of a plaintiff in an action brought under a fee-

shifting statute should be compensated not only for the time

expended prosecuting the action but also for the risk

associated with bringing the litigation. Without the

prospect of contingent risk enhancement, competent

attorneys, operating in accordance with market principles,

will decline to undertake such litigation, and those persons

intended to be benefited by the statutes containing the fee-

shifting provisions will be disserved.

Five Justices of this Court have acknowledged the

crucial role that contingent risk enhancement plays in the

legal services market. Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley

Citizens’ Council fo r Clean Air, 483 U.S. 711 (1987)

(Delaware Valley II) (O’Connor, J. concurring; Blackmun,

J. dissenting). In the five years that have elapsed since

Delaware Valley II, the two-part test set out in Justice

O’Connor’s concurring opinion has proved both workable

and fair. As applied by numerous lower courts, it has

yielded reasonable attorney’s fees awards, while furthering

Congress’ essential purpose: that those persons intended to

- 3-

be benefitted by fee-shifting legislation have access to

competent counsel willing and able to represent them.

The principal concern of the plurality in Delaware

Valley II — that an enhancement for a contingent risk

undermines the "prevailing party" requirement by

compensating counsel who prevail in one case for other

cases in which they do not prevail — is dispelled both by

sound economic analysis and by the post -Delaware Valley

II experiences and findings of federal courts in a number of

jurisdictions. These decisions fully validate what the

legislative history of Section 1988 teaches: when the

market is the measure of a reasonable attorney’s fees

award, a contingent risk enhancer is necessary and

appropriate to fulfill Congress’ intent that the public

interest statutes it enacts be enforced, and that competent

counsel be reasonably and fairly compensated for their

efforts to that end.

ARGUMENT

I. In Enacting Fee-shifting Statutes, Congress has

M andated that the Amount of Attorney’s Fees

Awarded to Prevailing Plaintiffs be Determined in

Accordance with Relevant Private M arkets for

Legal Services.

Although the instant case arises under the attorney’s

fee provisions of Section 7002 of the Solid Waste Disposal

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 6972(e), and Section 505 of the Clean

Water Act, 33 U.S.C. § 1365(d), this Court has determined

that the fee-shifting standards applicable to those statutes

are the same as those applicable under Section 1988 of the

Federal Civil Rights Attorney’s Fee Award Act of 1976, 42

U.S.C. § 1988. See, e,g., Pennsylvania v. Delaware

Valley Citizens’ Council fo r Clean Air, 478 U.S. 546, 560-

62 (1986) {Delaware Valley I). Central to the inter

pretation of all public interest attorney’s fees statutes,

therefore, is Senate Report No. 94-1011 (1976), which sets

out the legislative history of Section 1988. See, e .g ., Blum

v. Stens on, 465 U.S. 886, 893-95 (1984). Senate Report

No. 94-1011 bears on all facets of fee setting under

Congress’ fee-shifting statutes, including risk enhancement.

See, e.g., Delaware Valley 11, 483 U.S. at 723-24. The

most relevant portion of Senate Report No. 94-1011 states:

It is intended that the amount of fees awarded

under [§ 1988] be governed by the same standards

which prevail in other types of equally complex

Federal litigation, such as antitrust cases[,] and not be

reduced because the rights involved may be non-

pecuniary in nature. The appropriate standards, see

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1974), are correctly applied in such cases as

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 FRD 680 (N.D. Cal.

1974); Davis v. County o f Los Angeles, 8 EPD f 9444

(C.D. Cal. 1974); and Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 66 FRD 483 (W.D.

N.C. 1975). These cases have resulted in fees which

are adequate to attract competent counsel, but which

do not produce windfalls to attorneys. S.

S. Rep. No. 94-1011 at 6 (1976). The standard set out in

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express is stated in terms of

twelve factors: (1) The time and labor required; (2) the

novelty and difficulty of the questions; (3) the skill

requisite to perform the legal service properly; (4) the

preclusion of other employment by the attorney due to

acceptance of the case; (5) the customary fee; (6) whether

the fee is fixed or contingent; (7) time limitations imposed

by the client or the circumstances; (8) the amount involved

and the results obtained; (9) the experience, reputation, and

ability of the attorneys; (10) the "undesirability" of the

case; (11) the nature and length of the professional relation-

- 5-

ship with the client; and (12) awards in similar cases. 488

F.2d at 717-719. The legislative history of Section 1988

thus embraces a standard that includes risk enhancement.

It is noteworthy that in enacting Section 1988

Congress used as a reference point the highly contingent

field (for plaintiffs’ counsel) of federal antitrust litigation.

Given that reference, the antitrust field’s market model

should guide "the amount of fees awarded under" Section

1988 and similar statutes, absent express statutory language

or clear legislative history to the contrary. See, e.g.,

Hasbrouck v. Texaco, Inc., 879 F.2d 632, 636-37 (9th Cir.

1989) (applying the analysis of Justice O’Connor, concur

ring, in Delaware Valley II to fee enhancement under the

Clayton Act in a Robinson-Patman case).

Consistent with the legislative history of Section 1988,

this Court has repeatedly ruled, with rare exclusively

statutory exceptions, that the principles and practices of the

market determine both the amount and the components of

attorney’s fees awards under fee-shifting statutes. Missouri

v. Jenkins, 491 U.S. 274, 285 (1989) (in determining how

certain attorney’s fees award are to be calculated, this

Court has "consistently looked to the marketplace as [its]

guide to what is reasonable"). Thus, under Section 1988

this Court has held that private market practices mandate

that the prevailing party be awarded compensation for the

work of salaried attorneys and paralegals at their market

hourly billing rates, rather than on an actual cost basis.

See Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. at 894-895; Missouri v.

Jenkins, 491 U.S. at 287-89. This Court has also held that

both hourly rates and compensable time are determined

essentially as the market determines them, subject to

adjustment on the basis of considerations such as the

complexity and novelty of the legal issues and the quality

of the services rendered. See, e.g., Missouri v. Jenkins,

491 U.S. at 285-289, Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. at 894-95.

-6-

In addition, this Court has recognized that market

considerations mandate an upward adjustment of fees to

compensate for delay. Jenkins v. Missouri, 491 U.S. at

283-84. Furthermore, the Court has validated market

practices that permit attorneys to be awarded fees that

exceed the amount provided in contingency fees contracts,

Blanchard v. Bergeron, 489 U.S. 87, 96 (1989); that

permit attorneys to collect fees from damages, in addition

to court awards of fees, Venegas v. Mitchell, 495 U.S. 82

(1990); and that permit plaintiffs in certain class actions to

enter into settlements that include waivers of attorney’s

fees, Evans v. Je ffD , 475 U.S. 717 (1986). Finally, the

Court has held that full attorney’s fees are to be awarded

to prevailing plaintiffs even when their fees exceed by

multiples the amount of the damages award. See City o f

Riverside v. Rivera, A l l U.S. 561, 575 (1986).

With respect to contingent risk enhancement, Justice

White’s plurality opinion in Delaware Valley II, while

limiting the availability and the amount of contingent risk

enhancers, acknowledges the relevance of the market. 483

U.S, at 726-27. The plurality’s only real concern with full

contingent risk enhancement is that an award enhanced to

take account of risk might compensate prevailing plaintiffs’

attorneys for work they performed in other cases in which

their clients did not prevail. Id. at 724-25. As argued

more fully in Section II, however, the contingent risk

enhancer is the price that the market dictates plaintiffs

counsel should be paid for the services he or she rendered

in the case in which the plaintiff prevailed.

Congress is fully able, if it wishes, to delineate an

approach other than that of market analysis. See Crawford

Fittings Co. v. J.T. Gibbons, Inc., 482 U.S. 437, 442

(1987). Notably, Congress has demonstrated its ability

explicitly to preclude the award of contingent risk enhan

cers, if it so intends, as it did in the Individuals with

- 7-

Disabilities Education Act, ("IDEA"), 20 U.S.C. §§ MOO-

MSS (1988). As provided by Sections 1415(e)(4)(B) and

(C), a court may award "reasonable attorneys’ fees" to

prevailing plaintiffs, but "[n]o bonus or multiplier may be

used in calculating the fees awarded . . .

Further, it is relevant that Congress has considered

and rejected several attempts to eliminate enhancers, at

least against government defendants. In 1982, Senator

Hatch proposed an amendment to Section 1988 that would

have prohibited "awards based on contingency factors or

enhancers." S. 585, 97th Cong. 2d Sess. § 722A (1982).

In addition, four bills were introduced that would have

imposed a $75 per hour cap on attorney’s fees awarded to

plaintiffs who prevailed against government defendants, and

eliminated enhancers under all federal fee-shifting

provisions. Neither Senator Hatch’s amendment nor any of

the proposed bills passed. See S. 2802, 98th Cong., 2d

Sess. (1984); H.R. 5757, 98th Cong. 2d Sess. (1984); S.

1580, 99th Cong. 1st Sess. (1985); and H.R. 3181, 99th

Cong. 1st Sess. (1985). As recently as last year, an

amendment that would have limited attorney’s fees to 20%

of the total award was proposed as part of the Civil Rights

Act of 1991. 137 Cong. Rec. S 15338-39 (daily ed. Oct.

29, 1991). That proposed amendment also failed.-7

Congress has also set limits or caps on attorney’s fees

awards under specific statutory schemes. See e.g., 28

U.S.C. §§ 2412(d)(1)(A) and (2)(A)(1988) (fee awards

under the Equal Access to Justice Act "shall be based upon

prevailing market rates . . . except that . . . attorney fees

shall not be awarded in excess of $75 per hour . . .); 42

- Congress’ rejection of proposed amendments indicates that it

does not intend the law to include the provisions embodied in the

rejected amendments. C.f. Lapina v. Williams. 232 U.S. 78 (1914);

United States v. Great Northern R. Co. . 287 U.S. 144, 155 (1932).

- 8-

U.S.C. § 300aa-15(b) (1988) (fee awards under the

National Vaccine Injury Compensation Act of 1986 limited

to $30,000); 28 U.8.C. § 2678 (1988) (fees under Federal

Tort Claims Act limited to 20% of administrative

settlement; 25% of judgment or settlement); 42 U.S.C.

§406(b)(l) (1988) (fees under Social Security Act limited

to 25% of award); 22 U.S.C. § 277d-21 (1988) (fees under

American-Mexican Chamizal Convention Act of 1964

limited to 10%); 48 U.S.C. § 1424c(f) (1988) (fees for

claims regarding land under Organic Act of Guam limited

to 5% of award); 50 U.S.C. app. § 1985 (1990) (fees

under Japanese-American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948

limited to 10% of award).

Because Section 1988 and the statutes at issue here do

not by their terms preclude the use of contingent risk

enhancers, market practices are controlling. As described

more fully below, those practices are plainly consistent

with the award of attorney’s fee enhancers, at the courts’

discretion and under appropriate circumstances.

II. Application of M arket Principles and Practices

M andates that Prevailing Parties in Actions

Brought Under Fee-shifting Statutes be Awarded

Contingent Risk Enhancers.

The difficulty in determining appropriate attorney’s

fees awards in statutory fee-shifting cases is in part attribut

able to the confusion over the nomenclature used. Many

of the cases refer to "windfalls," "bonuses" or

"multipliers." The impression that this language conveys

is that a lawyer who seeks an enhancement for contingent

risk after prevailing in a fee-shifting case is somehow

seeking more than is properly due.

- 9 -

But that impression is false and misleading. As five

Justices in Delaware Valley II recognized, lawyers who

bring actions under fee-shifting statutes are simply operat

ing under the normal rules of the market in which they

operate. Ail practicing litigation attorneys know that they

charge a different rate depending on whether they will be

paid on a regular hourly basis or only if they win.

Whether the case is an antitrust case in Seattle, a personal

injury case in Boston, a securities fraud case in New York,

a patent infringement case in Philadelphia, an employment

discrimination case in San Francisco, a breach of contract

case in St. Louis or an environmental case in Vermont,

lawyers who are not assured of being compensated for their

efforts must, and do, negotiate their fees accordingly.

It is not a question of getting a "windfall" or a

"bonus" if one succeeds. Rather, the business and econom

ic reality is that statutory fee-shifting cases must be treated

differently, from a fees perspective, from cases for which

counsel is compensated on a risk-free hourly basis. In the

unregulated market for legal services, virtually all lawyers

charge either hourly rates that must be paid regardless of

outcome, or contingency fees that are paid only if the

lawyer succeeds. Contingency fees inevitably are higher,

so that prevailing lawyers are compensated for the

additional risk of a negative outcome. The American Bar

Association ("ABA") which monitors and enforces fee

setting practices in the legal profession, fully authorizes

attorneys to seek compensation for contingent risk.

Disciplinary Rule No. 2-106(B) of the ABA Model Code

and Rule 15 of the ABA Model Rules list the following

eight factors for determining the reasonableness of

attorney’s fee awards, including contingent risk:

(1) The time and labor required, the novelty and

difficulty of the questions involved, and the skill

requisite to perform the legal service properly;

- 10-

(2) The likelihood, if apparent to the client, that the

acceptance of the particular employment will

preclude other employment by the lawyer;

(3) The fee customarily charged in the locality for

similar legal services;

(4) The amount involved and the results obtained;

(5) The time limitations imposed by the client or by

the circumstances;

(6) The nature and length of the professional relation

ship with the client;

(7) The experience, reputation, and ability of the

lawyer or lawyers performing the services;

(8) Whether the fee is fixed or contingent. . . .

(Emphasis supplied.) Lawyers thus reasonably and

properly demand, and the market dictates, that in fee-

shifting litigation they be compensated for the contingent

risk inherent in plaintiff s-side fee-shifting litigation.

This Court has recognized that a "reasonable"

attorney’s fee award may provide contingent risk enhance

ment. In Department o f Labor v. Triplett, 494 U.S. 715

(1990), this Court upheld the attorney’s fees provision of

the Black Lung Benefits Act of 1972, 30 U.S.C. § 901 et

seq., which limits and regulates both the type of fee

arrangements available and the amount of fees

compensable, against the due process challenge of a

prevailing claimant’s attorney. The Court reasoned, inter

alia, that the statute by its terms provides for the award of

"reasonable" attorney’s fees, and that the Benefits Review

Board, which reviews challenged fee awards, "has con

strued the regulations of the Secretary of Labor governing

the award of attorney’s fees to permit consideration of the

-ll-

attorney’s risk in going unpaid." 494 U.S. a t ___, 108

L.Ed.2d at 717 (emphasis supplied).

The plurality in Delaware Valley 11 admitted that

"without the promise of risk enhancement some lawyers

will decline to take cases[,j" but the plurality nonetheless

remained confident that "the goal of the fee-shifting

statutes" will be achieved. The plurality in fact underes

timated the role of contingent risk enhancers in attracting

counsel "in any market where there are competent lawyers

whose time is not fully occupied by other matters." 483

U.S. at 725. In reality, virtually no contracts are made for

contingent representation at noncontingent hourly rates. To

restrict the use of enhancers — in the belief that plaintiffs

will always be able to find representation from lawyers

who do not place a higher "opportunity cost" on their time

— ignores the economic reality that even those clients who

are more empowered are unable to find such bargains. It

is unreasonable to impose a condition on compensation that

is virtually never accepted in voluntary agreements between

lawyers and their clients.

The plurality’s ultimate concern in Delaware Valley 11

was that contingent risk enhancement necessarily would

compensate "plaintiffs lawyers for not prevailing against

defendants in other cases." 483 U.S. at 725. But this is

simply not the case. The award of enhancers does not

compensate plaintiffs’ counsel for cases they may have lost;

rather, enhancers compensate for the risk associated with

the case or cases in which they prevail. The defendant

who loses a case brought under a fee-shifting statute thus

is not paying for plaintiffs counsel’s "losing" cases, any

more than a plaintiff in a personal injury case, who must

pay a contingency fee out of a damages award, is paying

for his or her lawyer’s losing cases. In each case the

contingency risk factor is simply a component of the

attorney’s reasonable compensation. Thus, if Dague were

-12-

the only case ever to arise under the Solid Waste Disposal

Act, the market would still drive respondents5 attorneys to

demand an appropriate risk-adjusted rate.

If the attorney’s fees provisions were interpreted to

limit fees awards to risk-free rates, then attorneys would

work on other cases that paid the market rate on a current,

risk-free hourly basis. Indeed, the dearth of attorneys

willing to take on certain types of public interest litigation,

as a result of the associated financial risk, is well

documented. See, e.g., Stemlight, The Supreme Court’s

Denial o f Reasonable Attorney’s Fees to Prevailing Civil

Rights Plaintiffs, 17 N.Y.U. Review of Law & Social

Change 535, 537-38 (1990) ("numerous attorneys have

been forced to withdraw from civil rights practice for

financial reasons. . . . The shortage of competent civil

rights attorneys has reached crisis proportions, a fact which

has been recognized by several state and federal courts,"

citing authorities); Terry, Eliminating the Plaintiff’s

Attorney in Equal Employment Litigation: A Shakespearean

Tragedy, 5 Lab. Law. 63 (1989) ("private counsel

representing plaintiffs in equal employment cases have

become an endangered species, in many places extinct");

U.S. v. City and County o f San Francisco, 748 F.Supp.

1416, 1434 (N.D. Cal. 1990) (documenting shortage of

employment discrimination counsel in San Francisco Bay

Area).

Of course some attorneys might still be willing to

provide what would amount to pro bono services by

working at less than the prevailing risk-adjusted rate.

Justice White has thus suggested in Delaware Valley II that

enhancers are not needed "in those cases where plaintiffs

secure help from organizations whose very purpose is to

provide legal help through salaried counsel to those who

themselves cannot afford to pay a lawyer." 483 U.S. at

726. Yet this argument ignores the fact that adequate

- 13-

attomey’s fees awards are a prerequisite to the continued

existence of these organizations. The argument is also

empirically refuted by the scant number of such

organizations. Delaware Valley II, 483 U.S. at 743

(Blackmun, J. dissenting). Further, if not-for-profit

organizations are not awarded fees commensurate with the

amounts attainable in the private market, they will not be

able to compensate as many attorneys at market rates.-

Moreover, in enacting fee-shifting statutes Congress

surely intended to do more than merely supplement the

eleemosynary efforts of the private bar. By including fee-

shifting provisions in Section 1988 and in the statutes at

issue here — and by not including limitations or prohibi

tions against contingent risk enhancers — Congress

expressed its intent that prevailing plaintiffs’ counsel be

compensated for assuming the risk of embarking on

complex federal fee-shifting litigation.

This approach has been followed in a variety of cases,

including antitrust cases, which set the model for statutory

fee-shifting litigation. As earlier noted, Section 1988 was

enacted against a backdrop of attorney’s fees enhancement

in the antitrust field. See City o f Detroit v. Grinnell Corp. ,

495 F.2d 448, 471 (2nd Cir. 1974) (antitrust: contingent

risk enhancer available because "despite the most vigorous

and competent of efforts, success [in litigation] is never

guaranteed"); Lindy Bros. Bldrs. v. American Radiator &

Standard Sanitary Corp., 487 F.2d 161, 168 (3rd Cir.

1973) (antitrust: lodestar may be enhanced to reflect

contingent nature); In re Coordinated Pretrial Proceedings,

- This Court has consistently held that the calculation of

attorney’s fees awards should not vary depending upon whether the

prevailing party was represented by a not-for-profit organization or

by private counsel. See Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. at 894;

Blanchard v. Bergeron, 489 U.S. at 95.

- 14-

410 F.Supp. 680, 691 (D. Minn. 1975) (antitrust:

enhancers awarded to "take the contingent nature of this

litigation . . . into consideration when awarding fees");

Blank v. Talley Indus., 390 F.Supp. 1, 5-6 (S.D.N.Y.

1975) (antitrust: fee award based in part on contingent

risk); In re Gypsum Cases, 386 F.Supp. 959, 961 (N.D.

Cal. 1974) (enhancer over normal hourly rates awarded in

seven-year antitrust case "in which, probably more than in

any other such litigation, the congressional objective of

private antitrust enforcement was realized"), a ff’d, 565

F.2d 1123 (9th Cir. 1977); Arenson v. Board o f Trade, 372

F.Supp. 1349, 1357-58 (N.D. 111. 1974) (enhancer over

normal hourly rate awarded in landmark antitrust case);

Chemer v. Transitron Elec. Corp., 221 F.Supp. 55, 61

(D.Mass, 1963) (antitrust: contingent risk enhancer

awarded because "[n]o one expects a lawyer whose com

pensation is contingent upon his success to charge, when

successful, as little as he would charge a client who in

advance had agreed to pay for his services, regardless of

success") modified on other grounds, 326 F.2d 492 (1st

Cir. 1964).

Contingent risk enhancers have also been awarded in

security fraud cases. See In re General Pub. Utils. Sec.

Litig., [1983-1984 Transfer Binder] Fed. Sec. L. Rep.

(CCH) 199,566, at 97,233-34 (D. N.J. Nov. 16, 1983)

(enhancer of 3.45); Steinberg v. Hardy, 93 F.Supp. 873,

873-74 (D. Conn. 1950) (securities: contingent risk enhan

cer awarded, with court noting: that "actions, even when

well-founded, will seldom be brought unless counsel can be

found" on a contingent basis; that "obviously a retainer on

a contingency basis is distinctly less attractive" than a

guaranteed hourly rate; and that "unless the courts recog

nize the need to fix [contingent case] compensation on a

more liberal basis," lawyers will not take these cases). See

also Class Action Reports, July-Aug., Sept.-Oct., 1990,

249 at 548 (surveying over 400 securities and antitrust class

- 15-

action cases from 1974 to 1990 and finding that, on

average, enhancers of 1.83 were awarded).

Contingent risk enhancers have been awarded in a host

of other areas governed by fee-shifting statutes. See Green

v. Transitron Elec. Corp., 326 F.2d 492, 496-97 (1st Cir.

1964) (stockholder’s derivative action affirming fee award

in part on contingent risk); County o f Suffolk v. LILCO,

710 F.Supp. 1477, 1481 (E.D.N.Y. 1989) (RICO case:

doubling of counsels’ hourly rate), a ffd in part, rev’d in

part on other grounds, 907 F.2d 1295 (2d Cir. 1990);

Municipal Audi, o f Bloomsburg v. Pennsylvania, 527

F.Supp. 982, 999-1000 (M.D. Pa. 1981) (enhancer,

characterized by court as "extremely high" and "probably

without precedent," awarded in case brought under Water

Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, 33 U.S.C.

§1251, et seq., because of "peculiar facts of this case"); In

re Cenco, Inc. Sec. Litig., 519 F.Supp. 322, 326-28 (N.D.

111. 1981) (enhancer awarded to lead counsel, whom court

praised for "very lean" staffing; other firms awarded lower

enhancer); Keith v. Volpe, 86 F.R.D. 565 , 575-77 (C.D.

Cal. 1980) (enhancer awarded in environmental protection

and civil rights action during period of high inflation);

Perlman v. Feldmann, 160 F.Supp 310, (D. Conn. 1958)

(attorney’s fees award in stockholder’s derivative action

giving "great weight" to contingent nature of case).

Post -Delaware Valley II cases are to the same effect.

See Purdy v. Security Savings and Loan Association, 727

F.Supp. 1266, 1279 (E.D. Wis. 1989) (enhancer over

normal hourly rate awarded in securities fraud case);

Lattimore v. Oman Const. Co., 714 F.Supp. 1178,1179

(N.D. Ala. 1989), a ffd , 868 F.2d 437 (11th Cir. 1989);

Hidle v. Geneva County Bd. o f Educ., 681 F.Supp. 752,

756-58 (M.D. Ala. 1988); Rievman v. Burlington Northern

Railway Co., 118 F.R.D. 29, 35 (S.D. N.Y. 1987)

(enhancer for complexity, risk and benefit to class).

- 16-

It is obvious that without the prospect of contingent

risk enhancers, lawyers are more likely to behave as the

market dictates they should — they will decline to take on

public interest litigation, in a variety of fields, to the detri

ment of the public intended by Congress to be benefitted by

the legislation containing the fee-shifting provisions. Judge

Brieant noted this economic fact of life in In re Union

Carbide, regarding securities fraud cases:

The award of attorneys’ fees in complex securities

class action litigation is informed by the public policy

that individuals damaged by violation of the federal

securities laws should have reasonable access to

counsel with the ability and experience necessary to

analyze and litigate complex cases. Enforcement of

the federal securities laws should be encouraged in

order to carry out the statutory purpose of protecting

investors and assuring compliance. . . . A large

segment of the public might be denied a remedy for

violations of the securities laws if contingent fees

awarded by the courts did not fairly compensate

counsel for the services provided and the risks under

taken. These policies further support the award of a

multiplier of counsel’s lodestar fee.

724 F.Supp. at 169 (emphasis supplied). The award of

contingent risk enhancers assures the enforcement of

federal public interest fee-shifting legislation — be it

antitrust, securities, environmental or civil rights legislation

— by reasonably and fairly compensating counsel who

prevail in actions brought under such statutes.

- 17-

III. Justice O ’Connor’s Approach in Delaware Valley I I

is a Fair and W orkable Way to Determine When

Risk Enhancement is Necessary to Assure that the

Prevailing Plaintiff is Awarded a Reasonable

A ttorney’s Fee in a Fee-Shifting Case.

Counting the four dissenting Justices and Justice

O’Connor, a majority of the Court in Delaware Valley II

deemed that contingent risk enhancement is appropriate at

least if the two prerequisites identified in Justice

O’Connor’s concurrence are met. First, the prevailing

party must establish that "without an adjustment for risk the

prevailing party ‘would have faced substantial difficulties

in finding counsel in the local or other relevant market.’"

483 U.S. at 733 (citation omitted). Second, any en

hancement for contingency must reflect "the difference in

market treatment of contingent fee cases as a class, rather

than . . . the ‘riskiness’ of any particular case." Id. at 731

(emphasis in original).

Justice O’Connor stated that:

[Djistrict courts and courts of appeals should treat

a determination of how a particular market compen

sates for contingency as controlling future cases

involving the same market. Haphazard and widely

divergent compensation for risk can be avoided only

if contingency cases are treated as a class; and contin

gency cases can be treated as a class only if courts

strive for consistency from one fee determination to

the next. Determinations involving different markets

should also comport with each other. Thus, if a fee

applicant attempts to prove that the relevant market

provides greater compensation for contingency than

the markets involved in previous cases, the applicant

-18-

should be able to point to differences in the markets

that would justify die different rates of compensation,

483 U.S. at 733.

Tying the amount of the enhancement to the market’s

treatment of similar contingent cases as a class eliminates

the parade of horribles postulated by the Delaware Valley

II plurality. Because the size of the enhancer would be

insensitive to the riskiness of any particular case, plaintiffs’

lawyers would still retain an incentive to take only those

cases which have the highest probability of success.

Conversely, class-based enhancement would not penalize

defendants who have the strongest cases, because the high

risk of plaintiffs’ loss in such cases would not increase the

enhancer. Consistent application of a class-based standard

would also reduce the amount of ex ante risk bom by the

attorneys, who would not need to worry that a court might

conclude ex post facto that the risk in a particular case did

not justify the normal enhancer. Application of the class-

based standard also ties the determination of a reasonable

attorney’s fee directly to Congress’ purpose: to create and

maintain a bar of competent counsel willing and able to

represent plaintiffs in public interest litigation.

Justice O’Connor’s approach is also eminently work

able. It places the burden on the petitioning attorney to

demonstrate that but for an enhancer the plaintiff would

have had substantial difficulty retaining competent counsel.

This burden can be fulfilled by looking to the voluntary

bargains struck in the marketplace by attorneys and their

clients. If the Delaware Valley II plurality’s "doubt”

proves valid, i.e., if enhancers are not necessary to attract

competent representation, then petitioning attorneys will

simply fail to meet their burden under Justice O’Connor’s

analysis.

- 19-

Since Delaware Valley II, a number of courts review

ing requests for fee enhancements have applied Justice

O Connor’s analysis fairly and without obvious admin

istrative difficulty. For example, in Islamic Center o f

Miss. v. Starkville, 876 F.2d 465, 472 (5th Cir. 1989), the

Fifth Circuit remanded the District Court’s denial of the

requested contingent risk enhancer because the court had

failed to make findings concerning the two prongs of

Justice O ’Connor’s test. The Fifth Circuit stated:

Justice O’Connor’s instructions in Delaware Valley

Citizens’ Council 11 are explicit: the district court

must consider whether a contingent enhancement

would have been necessary to induce competent

counsel to accept such cases at the time the case was

undertaken and whether contingency cases as a class

were treated differently from noncontingency cases.

Id. at 472. See also Leroy v. City o f Houston, 831 F.2d

576, 583-84 (5th Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 486 U.S. 1008

(1988) (trial court record and findings must support award

of enhancer).

The Sixth Circuit has also applied Justice O’Connor’s

test. See Conklin v. Lovely, 834 F.2d 543, 553-554 (6th

Cir. 1987) (remand where District Court failed to make

specific finding of fact as to amount and necessity of

enhancer awarded).

The Seventh Circuit has clearly adopted Justice

O’Connor’s test for awarding contingent risk enhancers in

cases where the evidence shows that without the enhance

ment plaintiffs would have faced substantial difficulties in

finding counsel in the local or other relevant market, and

that the relevant market compensates for contingent risk.

See Skelton v. General Motors Corp., 860 F.2d 250, 254

n.3 (7th Cir. 1988), cert, denied, 493 U.S. 810, (1989);

- 20-

Soto v. Adams Elevator Equipment Co., 941 F.2d 543, 553

(7th Cir. 1991); McGuire v. Sullivan, 873 F.2d 974, 978-

79 (7th Cir. 1989). Thus, in King v. Board o f Regents,

748 F.Supp. 686, 691-93 (E.D. Wis. 1990), a contingent

risk enhancer was awarded based on the testimony of

Milwaukee attorneys and the District Court’s observations

regarding the difficulty for plaintiffs in his court of finding

competent counsel to accept civil rights cases on a contin

gency fee basis. However, the District Courts in the

Seventh Circuit have not awarded contingent risk enhancers

when Justice O’Connor’s test was not found to have been

met. See Wolf v. Planned Property Management, 735

F.Supp. 882, 887 (N.D. 111. 1990); Leigh v. Eagle, 714

F.Supp. 1465, 1475-76 (N.D. 111. 1989).

The Eighth Circuit has applied Justice O’Connor’s

analysis in three cases. See Morris v. American National

Can Corp., 952 F.2d 200,204-07 (8th Cir. 1991);

Hendrickson v. Brendstad, 934 F.2d 158,162 (8th Cir.

1991); Jackson v. Rheem Manufacturing Co., 904 F.2d 15,

16-17 (8th Cir. 1990).

The Ninth Circuit first applied Justice O’Connor’s test

in Fadhl v. City and County o f San Francisco, 859 F.2d

649 (9th Cir. 1988), a case brought under Title VII. The

Ninth Circuit sustained the District Court’s award of a

contingent risk enhancer. The Ninth Circuit determined,

on unrebutted evidence concerning both the market and

plaintiffs difficulty in securing counsel, that within the

relevant market an enhancer was necessary to attract

competent counsel. Id. at 650-51.

In Hasbrouck v. Texaco, Inc., 879 F.2d 632 (9th Cir.

1989), a case arising under the Robinson-Patman Act, 15

U.S.C. § 13(a), and analogous Washington State law, the

Ninth Circuit sustained the District Courts’ pre-Delaware

- 21-

Valley II award of a contingent risk enhancer. The Court

specifically found:

In this case there is strong uncontroverted evi

dence on permissible factors to support the district

court’s award. We conclude that the district court did

not ‘enhance [the] fee award any more than necessary

to bring the fee within the range that would attract

competent counsel.’ Fadhl, 859 F.2d at 651 (quoting

Delaware Valley II, 483 U.S. at 733, 107 S.Ct. at

3091 (O’Connor, J. concurring)). We are also satis

fied that the evidence shows why the lodestar amount

would not be reasonable.

879 F.2d at 637. See also Oviatt v. Pearce, 92 D.A.R.

723, 728 (9th Cir. Jan. 16, 1992) (denial of enhancer ap

propriate where District Court had found that plaintiff had

failed to show, in the relevant Oregon market for the class

of cases involved, that "without an enhancement, plaintiffs

in similar [relatively simple damages cases] will face

substantial difficulties in finding counsel"); Bemardi v.

Yeutter, 951 F.2d 971, 975 (9th Cir. 1991) (reversal of

denial of enhancer and award of 2.0 enhancer, where

District Court had failed to "address whether sufficient

independent evidence had been presented that demonstrated

that San Francisco no longer has a ‘manifest need . . . for

fee enhancements in civil rights cases’ Fadhl, 859 F.2d at

651"); Bouman v. Block, 940 F.2d 1211, 1236 (9th Cir.

1991) (case remanded to the District Court "to consider

evidence of the market conditions in Los Angeles and

determine whether [plaintiff] is entitled to the 2.0 multiplier

she has requested or some other multiplier in excess of the

one and one third figure the district court judge used");

Merritt v. Mackey, 932 F.2d 1317 (9th Cir. 1991) (reversal

of a District Court’s enhancement of an attorney’s fee that

was itself based on the contingent risk inherent in bringing

the action); D ’Emanuele v. Montgomery Ward & Co. Inc.,

- 22-

904 F.2d 1379, 1384, 1387 (9th Cir. 1990) (reversal of

District Court’s denial of enhancer in ERISA action),

The Eleventh Circuit has also relied on Justice

O’Connor’s analysis in approving the award of contingent

risk enhancers, Lattimore v. Oman Construction, 868 F.2d

437, 439 (11th Cir. 1989) (per curiam). The Court

concluded that ”[a] fees award may be increased by 100%

to compensate attorneys for the risk of accepting a case on

a contingency basis and to attract competent counsel."

Richardson v. Alabama State Bd. ofEduc . , 935 F.2d 1240,

1248 (11th Cir. 1991).

These decisions fully validate Justice O’Connor’s

approach to contingent risk enhancement in federal fee-

shifting litigation. The courts applying Justice O’Connor’s

analysis have demonstrated their ability to elicit and

examine the relevant evidence and, on that basis, fairly

exercise their discretion to compensate prevailing counsel

for the market factor of contingent risk. This approach

thus is workable in practice and consistent in principle with

Congress’ intent that counsel be reasonably compensated

for their efforts in enforcing public interest legislation.

- 23-

CONCLUSION

For the forgoing reasons, the decision beiow should be

affirmed.

Rosen, Bien & Asaro

Sanford Jay Rosen

Counsel o f Record

Andrea G. Asaro

Adela B. Karliner

Stephen M. Liacouras

155 Montgomery Street, 8th Floor

San Francisco, California 94104

Telephone: (415) 433-6830

Steven R. Shapiro

John A. Powell

American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

Leon Friedman

Co-counsel for the American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

148 East 78th Street

New York, NY 10021

(212) 737-0400

Richard Larson

Mexican American Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

634 South Spring Street, 11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

- 24-

Julius L. Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Terisa E. Chaw

National Employment Lawyers Association

535 Pacific Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94133

(415) 397-6335

Dated: April 10, 1992

A PPENDIX

A-l

STATEMENTS OF INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Alabama Employment Lawyers Association

714 South 29th Street

Birmingham, AL 35233-2845

(205) 322-6631

The Alabama Employment Lawyers Association

(AELA) is a non-profit organization consisting of ap

proximately 25 lawyers who concentrate on the represen

tation of individual employees in employment and labor

matters. Some members of AELA are active in represen

ting employees in federal employment discrimination

matters, while others represent clients under the National

Labor Relations Act or state causes of action.

Members of AELA who handle individual employment

discrimination cases usually do so on a contingency fee

basis. Because the judges in the federal courts of Alabama

are inconsistent in the awarding of contingency enhancers,

those members find it difficult to devote much time to such

cases. If the Supreme Court eliminates the possibility of

recovering fees similar to what AELA’s members could

expect in the market place for other contingent work, they

will be forced to devote their time and resources to other

kinds of cases and to clients with federal employment

discrimination claims who can afford to pay fees on an

non-contingent basis.

American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

The American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

(ACLU) is a nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organiza

tion with nearly 300,000 members dedicated to the princi

ples embodied in the Bill of Rights and this nation’s civil

rights laws. Based on the experience of the ACLU, it is

A-2

clear that the availability of statutory attorney’s fees

calculated at fair market rates is critical in recruiting

private attorneys to undertake civil rights litigation and

thereby promote the values of the ACLU. In addition, the

ACLU’s own entitlement to attorney’s fees is a function of

market rates and, thus, any change in the way those rates

are calculated for attorney’s fee purposes directly affects

the work of the ACLU and its affiliates throughout the

country. For both of these reasons, the ACLU has a vital

interest in the outcome of this case.

Joaquin G. Avila, Esq.

1774 Clear Lake Avenue

Milpitas, CA 95035-7014

(408) 263-1317

Joaquin G. Avila is a solo practitioner. His entire

practice consists of representing plaintiffs in challenges to

electoral systems at various governmental and quasi-

govemmental levels. These challenges are based primarily

on the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, and/or the

United States Constitution. Mr. Avila takes all of these

cases on a pure contingency basis, and depends on court-

awarded attorney’s fees for a substantial portion of his

compensation. Without substantial enhancers to

compensate for the contingency of not being paid at all, he

would be forced to limit his practice and take on either

hourly-rate paying clients or contingency cases with the

promise of large monetary damages awards. Substantial

fee enhancements are necessary to make a contingency-

based practice such as Mr. Avila’s economically feasible.

A-3

Cooper, Mitch, Crawford, Kuykendall & Whatley

1100 Financial Center

505 Twentieth Street North

Birmingham, AL 35203

(205) 328-9576

Cooper, Mitch, Crawford, Kuykendall & Whatley, a

law firm of thirteen lawyers in Birmingham, Alabama,

represents labor unions throughout the Southeast. It also

has an active plaintiffs’ tort practice and represents the City

of Birmingham and historically black colleges in civil rights

matters.

In recent years, the firm has represented a large

number of individuals in employment discrimination cases.

Almost all of these cases are by necessity contingency fee

cases. Even with the contingency enhancers approved by

the Eleventh Circuit, it is difficult to make this part of the

practice financially productive. If the Supreme Court

eliminates the possibility of recovering enhanced fees, then

the firm will cease handling employment discrimination

cases on a contingency basis; instead, the firm will devote

its time and resources to other kinds of cases and to clients

who can afford to pay fees on a non-contingent basis.

Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, Inc.

2216 Sixth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

(510) 644-2555

The Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund,

Inc. (DREDF) is a national disability civil rights

organization dedicated to securing equal citizenship for

Americans with disabilities. DREDF pursues its mission

through education, advocacy and law reform efforts. In its

efforts to promote the full integration of citizens with

disabilities into the American mainstream, DREDF has

represented and/or assisted hundreds of people with

disabilities who have been denied their rights and excluded

A-4

from opportunities because of false and demeaning

stereotypes.

DREDF’s efforts to enforce federal statutes protecting

the rights of people with disabilities depend in large part on

its ability to work with the private bar in both individual

and class action lawsuits and to refer such cases to private

counsel. This ability would be seriously affected if there

were no possibility of enhancers to attorney’s fees awards

for contingent risk.

Jay-Alien Eisen Law Corporation

1000 G Street, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95814

(916) 444-6171

Jay-Allen Eisen Law Corporation is a private law firm

that does a significant amount of public interest work and

depends in part on fees recovered in these cases as a means

of financing these activities. The firm’s interest in this

case is to ensure that counsel performing legal services

which benefit the public are adequately compensated, and

will therefore be encouraged to continue performing these

legal services.

Erickson, Beasley, Hewitt & Wilson

12 Geary Street, 8th Floor

San Francisco, CA 94108

(415) 781-3040

Erickson, Beasley, Hewitt & Wilson is a twelve

lawyer firm with an active civil rights docket. This docket

has consisted primarily of the representation of plaintiffs

and plaintiff classes in complex civil rights matters in the

federal courts, often against the federal government.

All of these complex civil rights cases have been

contingency fee cases. Such cases are too complicated and

too time consuming — in summary, too expensive — for

A-5

any individual plaintiff or plaintiff class to pay the firm’s

billings. It has always been difficult to make this area of

the practice financially feasible. Without the possibility of

a fee award enhancement, the firm’s civil rights docket

would become financially impossible, and the firm would

have to drastically curtail its representation in this area of

the law.

Law Office of Alan B, Exelrod

660 M arket Street, Suite 300

San Francisco, CA 94104

(415) 392-2800

Alan B. Exelrod is a solo practitioner representing

plaintiffs in litigation involving employment and civil

rights. He has been engaged in this practice as a solo

practitioner for ten years and has been involved in civil

rights law since graduating from law school in 1968.

None of the plaintiffs Mr. Exelrod represents can

afford to pay him his full hourly rate. He therefore

assumes the risk of losing money every time he files a

lawsuit. Many of these cases are hard fought over a long

period of time. In calculating the economics of his prac

tice, enhancement of fees is central to his being able to

represent clients who cannot pay hourly fees. He generally

does not work with civil rights organizations but litigates

such cases on his own or with other private counsel.

Ferguson, Stein, W att, Wallas, Adkins

& Gresham, P.A.

700 East Stonewall Street, Suite 730

Charlotte, NC 28202

(704) 375-8461

Ferguson, Stein, Watt, Wallas, Adkins & Gresham,

P.A ., a 14-lawyer law firm, has devoted a substantial

portion of its practice to representing plaintiffs in civil

rights cases including school desegregation litigation,

A-6

voting rights litigation, and employment discrimination

litigation on a contingency basis. Most civil rights

plaintiffs do not have funds to hire attorneys on an hourly

basis. Very few lawyers in North Carolina are willing to

represent plaintiffs in civil rights cases when their fee will

be contingent. Because of the firm’s difficulty in obtaining

reasonable fees, the firm has decreased its civil rights

caseload over the past few years. If the Supreme Court

eliminates the opportunity to obtain fee enhancements in

cases that are contingent, it is likely that the firm will

continue to take fewer civil rights cases. Substantial fee

enhancements are necessary to make a contingency civil

rights practice viable.

The Law Offices of R ichard B. Fields

The W right Carriage House

688 Jefferson Ave.

Memphis, TN 38105

(901) 529-8503

Mr. Fields and his former partners have practiced civil

rights law in Memphis for over 20 years. His predecessor

firm, Ratner & Sugarmon, was the first integrated law firm

in Memphis and was involved in landmark civil rights

litigation involving school desegregation, employment

discrimination, police misconduct, and housing

discrimination. The firm served as counsel in landmark

civil rights cases before this Court, including Firefighters

Local Union 1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984), Brandon

v. Hold, 469 U.S. 464 (1985), and Dayton Board o f

Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979). All of this

work was undertaken on a contingency basis with the

expectation of court-awarded attorney’s fees. Enhanced

attorney’s fees awards are necessary to enable private law

firms to undertake civil rights litigation.

A-7

Julian, Olson & Lasker, S.C.

330 East Wilson Street

P.O . Box 2206

M adison, W I 53701-2206

(608) 255-6400

Julian, Olson & Lasker, S.C., is a three lawyer firm

that enjoys a reputation for cutting-edge constitutional and

civil rights litigation on behalf of plaintiffs. Its attorneys

have handled voting rights, school desegregation,

employment housing discrimination and other civil rights

cases across the country, many in cooperation with the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

Almost all of the firm’s plaintiffs’ cases are taken pursuant

to contingent fee arrangements, but because attorney’s fees

awards have not been adequate, the firm has been forced in

recent years to avoid cases in which its compensation will

be wholly derived from court-awarded attorney’s fees. The

firm has actively sought defense work and has begun to

require substantial retainers in contingent fee cases for

plaintiffs. Low income clients whose claims appear

meritorious but which lack substantial monetary damages

components are regularly turned away, and many of these

clients simply do not find lawyers to represent them at all.

Legal Services for Prisoners with Children

1535 Mission Street

San Francisco, CA 94103

(415) 255-7036

Legal Services for Prisoners with Children (LSPC) is

a legal services organization focusing on the needs of

prisoners, their children, and family members. Founded in

1978, LSPC provides litigation assistance to lawyers and

legal advocates working with prisoners and their families

on a wide range of civil legal issues. LSPC attorneys are

currently co-counsel in several class actions on behalf of

prisoners, parolees, and family members. LSPC joins this

amicus brief because it is deeply concerned about the

A-8

ability of prisoners and their families to obtain legal

counsel to represent them. There are few lawyers willing

to represent indigent prisoners, and eliminating the poten

tial for prevailing parties to recover enhanced attorney’s

fees awards would make it even harder for prisoners and

their families to obtain representation.

Legal Services of Northern California

515 Twelfth Street

Sacramento, CA 95814

(916) 444-6760

Legal Services of Northern California (LSNC) is a

private non-profit corporation organized and existing under

the laws of the State of California for the purpose of

delivering free legal assistance to individuals and groups

who meet income eligibility requirements. Founded thirty-

five years ago, LSNC maintains offices in five cities

serving 18 counties in northern California. Last year

alone, LSNC attorneys served more than 17,000 impover

ished citizens with critical legal problems.

In cooperation with local bar associations, LSNC

operates Voluntary Legal Services Program of Northern

California, providing legal assistance in civil law matters

through referrals to private attorneys. LSNC’s interest in

this case is to preserve its ability to refer cases to the

private bar, and to attract competent counsel for such

referrals.

Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund

634 South Spring Street, 11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 629-2612

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund (MALDEF) is a national civil rights organization

established in 1967. Its principal objective is to secure,

through litigation and education, the civil rights of His-

A-9

panics living in the United States. In order to pursue this

objective — particularly with regard to vindicating the

rights of Hispanics to be free from discrimination in

education, employment, and full political participation —

MALDEF relies heavily on private practitioners acting as

cooperating attorneys to represent Hispanics who have been

the victims of discrimination. These private attorneys, who

are paid neither by MALDEF nor by their impecunious

clients, undertake such legal representation in reliance on

market-based statutory fee awards paid only at the conclu

sion of cases in which their clients have prevailed. Only

through fee awards which take into account the manner in

which contingency risk operates in the marketplace can

Hispanics have any chance of vindicating their statutory

and constitutional rights in court.

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. (LDF) is a non-profit organization organized as a legal

aid society under the laws of the State of New York. It

was formed to assist African Americans in securing their

constitutional rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. LDF

depends on members of the private bar, most of whom are

single practitioners or in small firms, to associate with it as

co-counsel in order to carry out its work. These attorneys,

in turn, depend on the availability of attorney’s fees under

the various civil rights statutes to be able to participate in

complex and time-consuming federal litigation. LDF has

participated as counsel and as amicus curiae in most of the

leading attorney’s fees cases in this and other courts. For

the above reasons, LDF has a vital interest in the outcome

of this case.

A-10

National Employment Lawyers Association

535 Pacific Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94133

(415) 397-6335

The National Employment Lawyers Association

(NELA) (Advocates for Employee Rights) is a non-profit

corporation with over 1100 lawyer members in 49 states.

Its members specialize in representing individual employees

in employment rights cases. Most NELA members

regularly handle discrimination cases under various civil

rights statutes that provide for attorney’s fees for the

prevailing plaintiff. NELA and its members are constantly

litigating "multiplier" fee enhancement issues in federal

court and are deeply concerned about the necessity of

obtaining a reasonable enhancement as ail incentive to

ensure that lawyers are available for victims of discriminat

ion.

Patterson, Harkavy, Lawrence, Van Noppen & Okun

206 New Bern Place

P .O . Box 27927

Raleigh, NC 27611

(919) 755-1812

Patterson, Harkavy, Lawrence, Van Noppen & Okun

is an eight lawyer firm with offices in Raleigh and

Greensboro, North Carolina. Historically, a significant

part of the firm’s practice has involved the representation

of plaintiffs in employment discrimination and

constitutional tort litigation. The vast majority of these

plaintiffs are unable to pay hourly fees and hence, if they

are to pursue their claims, representation must be on a

contingent basis.

Firms such as Patterson, Harkavy, can take such cases

only if the compensation we receive for successful public

interest litigation exceeds fees generated by other work

where compensation is non-contingent. The firm cannot

A -n

continue to turn away clients who will pay on an hourly

basis at market rates in favor of cases where the firm risks

spending hundreds of hours without compensation, and

then, if it prevails, can expect to receive only the same

hourly fee it would have received, without risk, from other

clients. Nor can public interest litigation compete with

other traditional contingent cases where success normally

results in fees substantially in excess of the firm’s non

contingent hourly rate. Unless fees awarded by courts for

successful public interest litigation reflect the market

practice of enhanced compensation for contingent work,

access to the courts for clients with claims of constitutional

violations and discrimination will effectively be denied.

R ichard M . Pearl

685 M arket Street, #370

San Francisco, CA 94105

(415) 243-9912

Richard M. Pearl is a sole practitioner. He is the

author of California Continuing Education of the Bar’s

California Attorney’s Fee Awards Practice and its annual

supplements, and is a member of the California State Bar’s

Attorney’s Fees Task Force. In his practice, he has

represented numerous profit and non-profit law firms

claiming court awarded attorney’s fees, and also has served

as an expert witness for both fee claimants and opponents.

Through that experience, he has seen first hand the monu

mental risk and commitment undertaken by attorneys who

are willing to represent victims of civil rights and

environmental law violations. The prospect of receiving a

fee that will recognize that risk, as the private market does,

is crucial to permitting and encouraging those attorneys to

continue in this field. Without a fee that recognizes risk,

the simple demands of the market will drive even the most

committed attorneys out of the field, undermining

Congress’s purpose in providing fee-shifting statutes.

A-12

Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California

1029 K Street, Suite 24

Sacramento, CA 95814

(916) 446-5247

Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California (PPAC) is

a non-profit corporation organized and existing under the

laws of the State of California. PPAC’s members are 16

local Planned Parenthood affiliate agencies throughout

California that provide comprehensive family planning