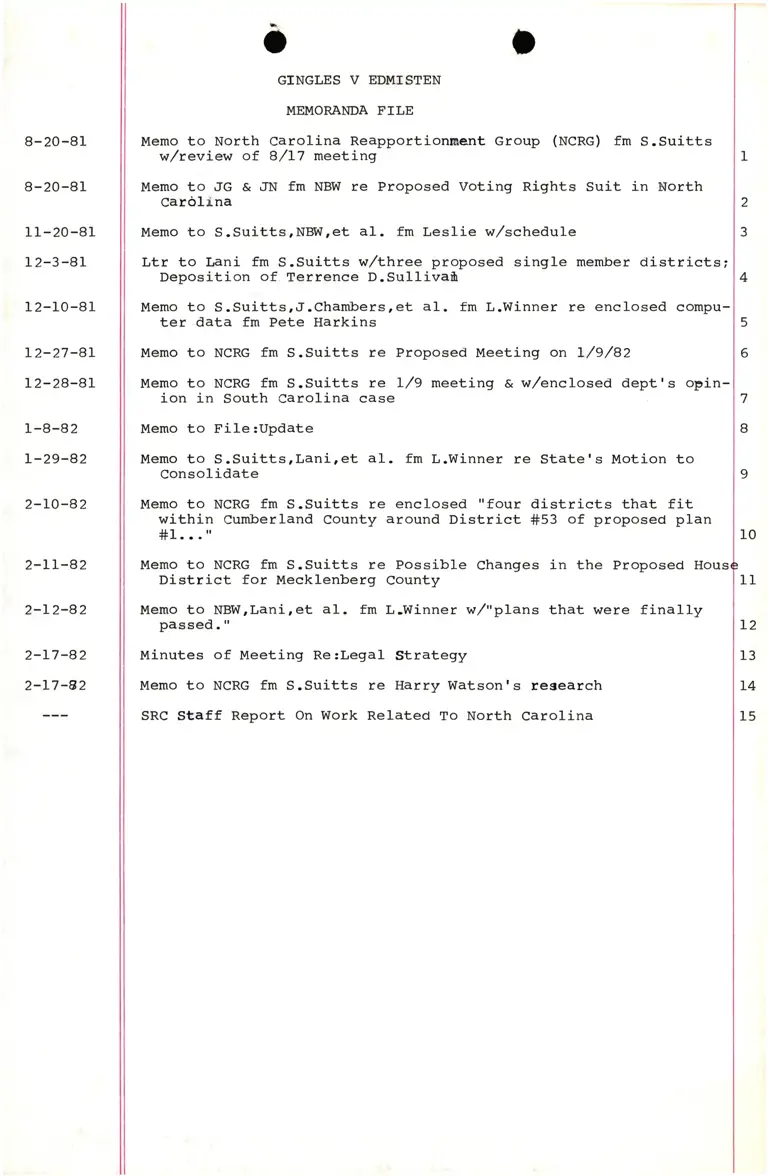

Gingles v. Edmisten Memoranda File Index

Working File

August 20, 1981 - February 17, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Gingles v. Edmisten Memoranda File Index, 1981. 99270dd2-d692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/632e8b38-23be-4920-a1e0-d2ce25f4bd02/gingles-v-edmisten-memoranda-file-index. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

8-20-81

8-20-81

11-20-81

I 2-3 -81

1 2-10-81

L2-27-8L

12-28-81

1 -8-8 2

L-29-82

2-LO-82

2-LL-82

2-L2-82

2-L7-82

2-L7-82

i

o

GINGLES V EDI{ISTEN

MEMORAIIDA FILE

Memo to North Carolina Reapportionne.nt Group (NCRG) fm S.Suitts

w,/review of 8/L7 meeting

Memo to JG & .IN fm NBVI re Proposed Voting Rights Suit in North

Carolina

Ivlemo to S.Suitts,NBVIret al. fm LesIie w/schedule

Ltr to Lani fm S.Suitts w,/three proposed single member districts;

Deposition of Terrence D.Sullivat

Memo to S.SuittsrJ.Chambers,et aI. fm L.Winner re enclosed compu-

ter data fm Pete Harkins

Memo to NCRG fm S.Suitts re Proposed Meeting on L/9/82

Memo to NCRG fm S.Suitts re l/9 meeting * w,/enclosed dept's opin-

ion in South Carolina case

Memo to File:Update

Memo to S.Suitts,Laniret aI. fm L.Winner re State's Motion to

Consolidate

Memo to NCRG fm S.Suitts re

within Cumberland County

#1...,'

I\,Iemo to NCRG fm S.Suitts re

District for Mecklenberg

Memo to NBI,{rlani,et aI. fm

enclosed "four districts that fit

around District #53 of proposed plan

Possible Changes in the Proposed Hous

County

L.Winner w,/"plans that were finally

passed. "

Minutes of Meeting Re:Legal Strategy

Ivlemo to NCRG fm s.suitts re Harry watsonrs research

SRC Staff Report On Work Related To North Carolina

2

3

5

6

7

I

10

11

l2

13

L4

15