Certificate of Service for Supplemental Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

April 19, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Certificate of Service for Supplemental Brief for Appellees, 1985. 03767f37-de92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/636abbe7-c06b-4cd0-9e46-8cb4c9ee6987/certificate-of-service-for-supplemental-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

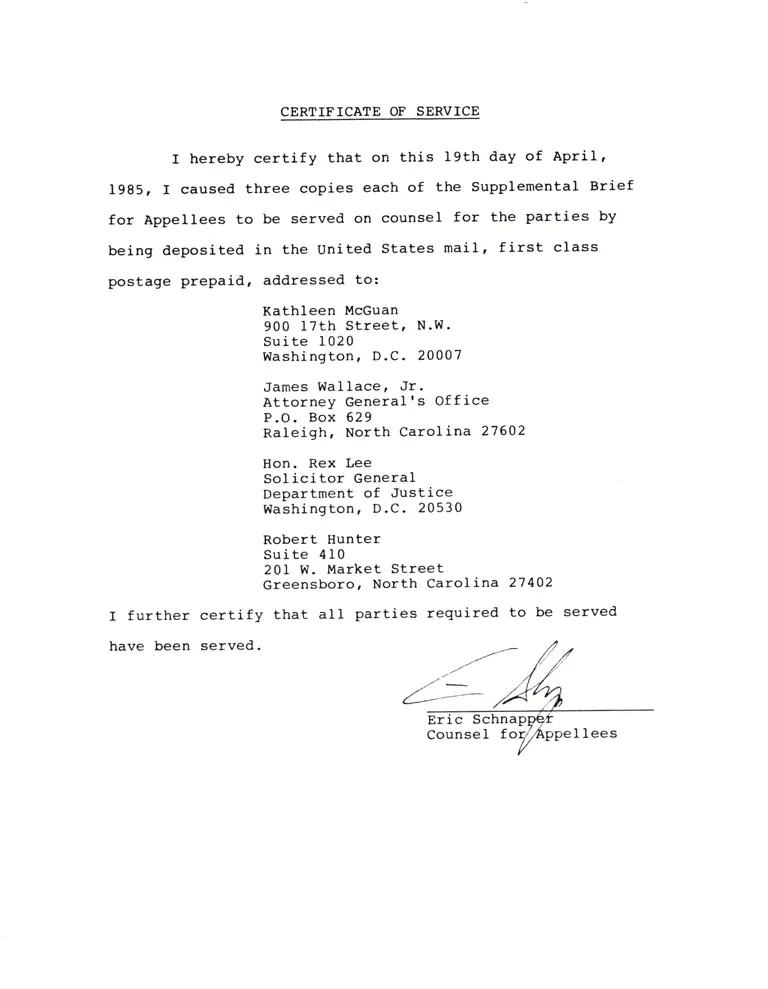

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 19th day of April,

1985, I caused three copies each of the Supplemental Brief

for Appellees to be served on counsel for the parties by

being deposited in the united states mail, first class

postage prePaid, addressed to:

Kathleen McGuan

900 ITth Street, N.W.

Suite f020

Washington, D.C.20007

James Wallace, Jr.

Attorney General's Office

P.O. Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Hon. Rex Lee

Soticitor General

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

Robert Hunter

I further certifY

have been served.

Suite 410

201 W. Dlarket Street

Greensboro, North Carolina 27402

that all parties required to be served

Eric Schna

Counsel fo ppel lees