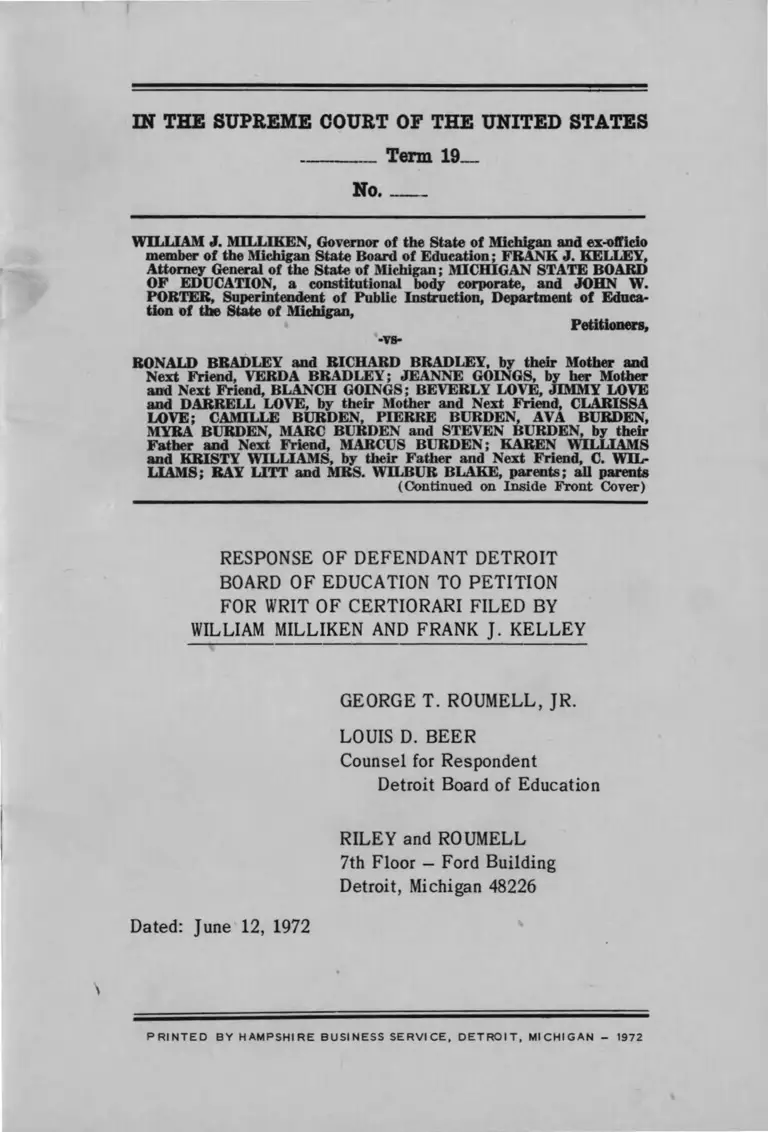

Response of Defendant to Petition for Writ of Certiorari Filed by William Milliken and Frank J. Kelley

Public Court Documents

June 12, 1972

29 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Response of Defendant to Petition for Writ of Certiorari Filed by William Milliken and Frank J. Kelley, 1972. 06a7d893-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/63c4993f-6e98-4940-b52f-ec8e27e0bb03/response-of-defendant-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-filed-by-william-milliken-and-frank-j-kelley. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

__ Term 19__

No_____

WILLIAM J. MILLIKEN, Governor of the State of Michigan and ex-officio

member of the Michigan State Board of Education; FRANK J. KELLEY,

Attorney General of the State o f Michigan; MICHIGAN STATE BOARD

OF EDUCATION, a constitutional body corporate, and JOHN W.

PORTER, Superintendent of Public Instruction, Department o f Educa

tion of the State of Michigan,

Petitioners,

-vs-

RONALD BRADLEY mid RICHARD BRADLEY, by their Mother and

Next Friend, VERDA BRADLEY; JEANNE GOINGS, by her Mother

and Next Friend, BLANCH GOINGS; BEVERLY LOVE, JIMMY LOVE

and DARRELL LOVE, by their Mother and Next Friend, CLARISSA

LOVE; CAMILLE BURDEN, PIERRE BURDEN, AVA BURDEN,

MYRA BURDEN, MARC BURDEN and STEVEN BURDEN, by their

Father mid Next Friend, MARCUS BURDEN; KAREN WILLIAMS

and KRISTY WILLIAMS, by their Father and Next Friend, C. WIL

LIAMS; RAY LITT and MRS. WILBUR BLAKE, parents; all parents

(Continued on Inside Front Cover)

RESPONSE OF DEFENDANT DETROIT

BOARD OF EDUCATION TO PETITION

FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI FILED BY

WILLIAM MILLIKEN AND FRANK J. KELLEY

GEORGE T. ROUMELL, JR.

LOUIS D. BEER

Counsel for Respondent

Detroit Board of Education

RILEY and ROUMELL

7th Floor - Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Dated: June 12, 1972

P R I N T E D B Y H A M P S H I R E B U S I N E S S S E R V I C E , D E T R O I T , M I C H I G A N - 1972

having children attending the public schools of the City of Detroit,

Michigan, on their own behalf and on behalf of their minor children,

all on behalf o f any person similarly situated; and NATIONAL ASSO

CIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, DE

TROIT BRANCH; DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL

231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO; BOARD

OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF DETROIT, a school district of

the first class; PATRICK McDONALD, JAMES HATHAWAY and

CORNELIUS GOLIGHTLY, members of the Board of Education of

the City of Detroit; and NORMAN DRACHLER, Superintendent of

the Detroit Public Schools; ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF BERKLEY, BRANDON

SCHOOLS, CENTERLINE PUBLIC SCHOOLS, CHERRY HILL

SCHOOL DISTRICT, CHIPPEWA VALLEY PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF CLAWSON, CRESTWOOD

SCHOOL DISTRICT, DEARBORN PUBLIC SCHOOLS, DEARBORN

HEIGHTS SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 7, EAST DETROIT PUB

LIC SCHOOLS, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF FERNDALE,

FLAT ROCK COMMUNITY SCHOOLS, GARDEN CITY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, GIBRALTAR SCHOOL DISTRICT, SCHOOL DISTRICT

OF THE CITY OF HARPER WOODS, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE

CITY OF HAZEL PARK, INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL DISTRICT OF

THE COUNTY OF MACOMB, LAKE SHORE PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

LAKE VIEW PUBLIC SCHOOLS, THE LAMPHERE SCHOOLS, LIN

COLN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, MADISON DISTRICT PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, MELVINDALE-NORTH ALLEN PARK SCHOOL DIS

TRICT, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF NORTH DEARBORN HEIGHTS,

NOVI COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT, OAK PARK SCHOOL DIS

TRICT, OXFORD AREA COMMUNITY SCHOOLS, BEDFORD UNION

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, RICHMOND COMMUNITY SCHOOLS,

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF RIVER ROUGE, RIVER-

VIEW COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT, ROSEVILLE PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, SOUTH LAKE SCHOOLS, TAYLOR SCHOOL DISTRICT,

WARREN CONSOLIDATED SCHOOLS, WARREN WOODS PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, WAYNE-WESTLAND COMMUNITY SCHOOLS, WOOD-

HAVEN SCHOOL DISTRICT and WYANDOTTE PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

KERRY and COLLEEN GREEN, by their Father and Next Friend,

DONALD G. GREEN, JAMES, JACK and KATHLEEN ROSEMARY,

by their Mother and Next Friend, EVELYN G. ROSEMARY, TERRI

DORAN, by her Mother and Next Friend, BEVERLY DORAN, SHER

RILL, KEITH, JEFFREY and GREGORY COULS, by their Mother

and Next Friend, SHARON COULS, EDWARD and MICHAEL ROMES-

BURG, by their Father and Next Friend, EDWARD M. ROMESBURG,

JR., TRACEY and GREGORY ARLEDGE, by their Mother and Next

Friend, AILEEN ARLEDGE, SHERYL and RUSSELL PAUL, by their

Mother and Next Friend, MARY LOU PAUL, TRACY QUIGLEY, by

her Mother and Next Friend, JANICE QUIGLEY, IAN, STEPHANIE,

KARL and JAAKO SUNI, by their Mother and Next Friend, SHIRLEY

SUNI, and TRI-COUNTY CITIZENS FOR INTERVENTION IN FED

ERAL SCHOOL ACTION NO. 35257; DENISE MAGDOWSKI and

DAVID MAGDOWSKI, by their Mother and Next Friend, JOYCE

MAGDOWSKI; DAVID VIETTI by his Mother and Next Friend,

VIOLET VIETTI, and the CITIZENS COMMITTEE FOR BETTER

EDUCATION OF THE DETROIT METROPOLITAN AREA, a Mich

igan non-Profit Corporation, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY

OF ROYAL OAK, SOUTHFIELD PUBLIC SCHOOLS, GROSSE

POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

Respondents.

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

NO_____________

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD BRADLEY, et al

Respondents.

RESPONSE OF DEFENDANT DETROIT

BOARD OF EDUCATION TO PETITION

FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI FILED BY

WILLIAM MILLIKEN AND FRANK J. KELLEY

Defendant DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION, pursuant

to U.S.S. Ct. Rule 21 (4), in response to the Petition for Writ

of Certiorari filed by WILLIAM MILLIKEN and FRANK J.

KELLEY, co-defendants herein, in partial support for the

aforesaid petition, states as follows:

I.

Respondent DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION supports

the Petition for Writ of Certiorari and agrees with petitioners

MILLIKEN and KELLEY that the order issued by the District

Court in this cause on September 27,1971 was ripe for appeal,

and that the action of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit in dismissing the appeals of petitioners MILLIKEN

and KELLEY and respondent DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCA

TION was erroneous, for reasons set forth in this respondent’ s

brief to the Court of Appeals, filed on February 3, 1972, and

set forth in the Appendix hereto.

- 2 -

II.

Although petitioners raise and discuss two substantive

questions in their petition, respondent DETROIT BOARD OF

EDUCATION does not understand them by this petition to ask

for review of any issue other than whether the dismissal of

the previous appeals by the Court of Appeals was proper.

Therefore, it does not appear necessary to state a detailed

response to questions II and III as raised by petitioners.

As a matter of record the DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCA

TION agrees with petitioners insofar as petitioners argue

that the record in the trial court does not support a finding of

the existence of a dual school system in the Detroit Public

Schools or justify any remedy. If it should be found that some

kind of remedy is appropriate, insofar as the petitioners argue

that as a matter of law any remedy ordered must be restricted

to the jurisdiction of the School District of the City of Detroit,

and may not involve schools operated by other agencies of the

State of Michigan, respondent DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCA

TION disagrees.

CONCLUSION

While agreeing in part and disagreeing in part with peti

tioners other contentions, respondent DETROIT BOARD OF

EDUCATION supports the Petition for Writ of Certiorari for

the purpose of reviewing the dismissal of appeals by the Court

of Appeals.

Respectfully submitted

GEORGE T. ROUMELL, JR.

LOUIS D. BEER

Counsel for Respondent

Detroit Board of Education

Riley and Roumell

7th Floor - Ford Building

Dated: June 12, 1972 Detroit, Michigan 48226

- A l -

APPENDIX

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO__

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

vs.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Cross-Appellee,

Defendants-Appellees,

Cross-Appellants,

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 231,

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendant-Intervenor-

Appellee,

Defendants-Intervenor.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Michigan

Southern Division

ANSWER OF DEFENDANTS BOARD OF EDUCATION

FOR THE

CITY OF DETROIT TO MOTION TO DISMISS APPEALS

- A2 -

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE

Is the order dated November 5, 1971, which incorporates

the final findings of fact and conclusions of law that the De

fendants Board of Education for the City of Detroit, et al have

committed acts amounting to de jure segregation of the Detroit

public schools contained in the District Court’ s Ruling on the

Issue of Segregation, and which directs the Board to submit a

plan of desegregation and an appealable order?

The Defendants Board of Education contend “ yes” .

\

- A3 -

Defendants-Appellees, Cross-Appellants, the Board of Ed

ucation for the City of Detroit, et al (hereinafter referred to as

Board of Education) respectfully moves this Honorable Court to

deny the Motion to Dismiss Appeals filed herein by Plaintiffs-

Appellants and Cross-Appellees, for the reason that this Honor

able Court has jurisdiction of this matter at this time because

(1) the order appealed from by the Board of Education is a final

order within the meaning of 28 U.S.C. 1291, or in the alternative,

(2) is an appealable interlocutory order pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

1292 (a) (1).

In support of their prayer that the Motion to Dismiss should

be denied as to their appeal, the Board of Education, et al show

the following:

STATEMENT OF PROCEDURAL FACTS

Plaintiffs commenced this litigation filing a complaint on

August 18, 1970 against the Board of Education of the City of

Detroit, its members and the then Superintendent of Schools, as

well as the Governor, Attorney General, State Board of Educa

tion and State Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State

of Michigan. Plaintiffs challenged the constitutionality of Act

48 of the Public Acts of 1970 of the State of Michigan as it af

fected certain plans of the Detroit Board of Education, and also

alleged that the Detroit Public School System was and is segre

gated on the basis of race as a result of the official policies and

actions of the Board of Education. After making said allegations,

the Plaintiffs in two and one-half pages of pleadings asked for

certain relief including preliminary injunctions requiring the

Board of Education to implement a plan of desegregation known

as the “ April 7, 1970” plan restraining implementation of the

aforementioned Act No. 48 of Michigan Public Acts of 1970, re

straining the Board of Education from all further school construc

tion and requesting permanent decrees concerning the above, and

enjoining the Board of Education from building schools, approv-

- A4 -

ing policies, curriculum and programs “ which are designed to or

have the effect of maintaining, perpetuating and supporting racial

segregation in the Detroit School System” and ordering Defendant

School Board to institute a plan of desegregation.

This case was initially tried on Plaintiffs’ motion for pre

liminary injunction to restrain the enforcement of the aforemen

tioned Act 48 so as to permit the so-called April 7, 1970 plan to

be implemented. The trial court ruled that the Plaintiffs were not

entitled to a preliminary injunction, did not rule on the constitu

tionality of Act 48, and granted a motion dismissing the cause

as to all of the State Defendants.

This Court, in Bradley v. M illiken, 433 F. 2d 897 , 989 (6th

Cir. 1970), held that the Trial Court did not abuse its discretion

in denying the motion for preliminary injunction, but, reversing

the trial court in part, held that portions of Act 48 were uncon

stitutional and that the State Defendants should remain in the

suit. By so doing, this Court recognized that at that time it had

jurisdiction to hear the appeal, even though the matter was still

pending in the lower court and there had not then been a trial

on the merits.

Subsequently, the Plaintiffs sought to have the Trial Court

direct the Defendant, Detroit Board, to implement the “ April

7th” plan prior to trial. The Court did not order implementation

of the “ April 7th” plan, but, instead, adopted a plan submitted

by the Board of Education.

Plaintiffs again appealed to this Court, and again, the Court

held that the Trial Court had not abused its discretion in refus

ing to adopt the April 7, 1970 plan. This Court furthermore re

manded with instructions to proceed immediately to a trial on the

merits of Plaintiffs’ allegations about the Detroit School System.

Bradley v. M illiken, 438 F. 2d 946 (6th Cir. 1971). Again this

x Court did not question its jurisdiction to hear the second appeal,

even though there had been no trial on the merits, but, instead,

- A5 -

denied Plaintiffs the relief sought on grounds other than juris

dictional.

The trial on the issue of segregation began April 6, 1971

and was concluded on July 22,1971 after consuming 41 trial days.

On September 27, 1971, the Trial Court issued a “ Ruling on

Issue of Segregation” which is attached as Appendix A to the

Plaintiffs’ motion herein.

In that ruling at page 25 (see Appendix A of Plaintiffs’

motion), the Court stated with particular finality:

In conclusion, however, we find that both the State

of Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education have

committed acts which have been causal factors in

the segregated condition of the public schools of

the City of Detroit. As we assay the principles es

sential to a finding of de jure segregation, as out

lined in rulings of the United States Supreme Court,

they are: . . . ”

And at page 34 of the ruling, the Court stated:

“ Having found a de jure segregated public school

system in operation in the City of Detroit, our

first step, in considering what judicial remedial

steps must be taken . . . ”

Pursuant to the above ruling, a pre-trial conference was

held on Monday, October 4, 1971, the transcript of which has

been attached to Plaintiffs’ motion herein as Appendix B. As

the transcript reveals the entire purport of the pre-trial con

ference on October 4, 1971 was directed towards a remedy im

plementing the Court’ s ruling.

This pre-trial conference concluded with the Court setting

a time table for the presentation of proposed implementation

- A6 -

plans. Though counsel for Plaintiffs has suggested that at

page 29 of the pre-trial transcript that the then counsel for the

Board of Education waived the entering of an order, the Court

did enter its order of November 5, 1971, which is attached to

Plaintiffs’ motion as Appendix C, set forth therein the time

table for the presentation of plans, and confirmed that as far as

the Trial Court was concerned, its findings of fact and conclu

sions of law on the issue of segregation had been made and

were final.1 Furthermore, in their motion now before this Court,

the Plaintiffs at page 6 concede that the Defendants had the

right to insist on an order being entered.

It is also noted that the Trial Court had previously issued

an injunction prohibiting the Defendant School Board from con

structing any new school buildings. That order still remains

in effect and the Court has enforced it and intends to do so as

the Court’ s attached letter marked Appendix J attached hereto

indicates.

ARGUMENT

REASONS WHY THE MOTION TO

DISMISS APPEAL SHOULD BE DENIED

INTRODUCTION

This Court has jurisdiction over the Appeal of Board of

Education from the Order of November 5, 1971 either as a final

decision under 28U.S.C. 1291; as the term “ final decision”

has been interpreted by the United States Supreme Court, by

the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and by other Circuits;

28 U.S.C. 1291 reads in part:

“ The Courts of Appeals shall have jurisdiction of

1 A s to th is confirmation, the Court’ s attention is directed to the Trial

Court’ s language at the outset o f its order o f Novem ber 5, 1971: “ The

Court having entered its find ings of fact and con clu s ion s o f law on the

issu e o f segregation on September 27, 1971;’ ’

- A7 -

appeals from all final decisions of the district courts

of the United States . . . ”

If this Court does not deem the Order to be a “ final de

cision” within the meaning of §1291, then the only possible

alternative interpretation is that the Order is interlocutory

and in the nature of an injunction from which appeals are per

mitted pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1292(a) (1):

“ (a) The courts of appeals shall have jurisdiction

9

of appeals from:

(1) Interlocutory orders of the district courts

of the United States, the United States District

Court for the District of the Canal Zone, the Dis

trict Court of Guam, and the District Court of the

Virgin Islands, or of the judges thereof, granting,

continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving in

junctions, or refusing to dissolve or modify in

junctions, except where a direct review may be

had in the Supreme Court;”

I.

THE ORDER OF NOVEMBER 5, 1971 IS A FINAL

DECISION WITHIN THE MEANING OF 28 U.S.C.

1291 AS THE TERM “ FINAL DECISION” HAS

BEEN INTERPRETED BY THE UNITED STATES

SUPREME COURT, 6TH CIRCUIT AND OTHER

CIRCUITS.

It is ineluctable fact that none of the issues of fact or

law raised in Plaintiffs’ complaint or Defendants’ answer re

main before the Trial Court. All were disposed of by the

“ Ruling on Issue of Segregation” of September 27, 1971, and

the subsequent order incorporating that Ruling on November

5, 1971. All that remains is to fashion a remedy.

- A6 -

plans. Though counsel for Plaintiffs has suggested that at

page 29 of the pre-trial transcript that the then counsel for the

Board of Education waived the entering of an order, the Court

did enter its order of November 5, 1971, which is attached to

Plaintiffs’ motion as Appendix C, set forth therein the time

table for the presentation of plans, and confirmed that as far as

the Trial Court was concerned, its findings of fact and conclu

sions of law on the issue of segregation had been made and

were final.1 Furthermore, in their motion now before this Court,

the Plaintiffs at page 6 concede that the Defendants had the

right to insist on an order being entered.

It is also noted that the Trial Court had previously issued

an injunction prohibiting the Defendant School Board from con

structing any new school buildings. That order still remains

in effect and the Court has enforced it and intends to do so as

the Court’ s attached letter marked Appendix J attached hereto

indicates.

ARGUMENT

REASONS WHY THE MOTION TO

DISMISS APPEAL SHOULD BE DENIED

INTRODUCTION

This Court has jurisdiction over the Appeal of Board of

Education from the Order of November 5, 1971 either as a final

decision under 28U.S.C. 1291; as the term “ final decision”

has been interpreted by the United States Supreme Court, by

the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and by other Circuits;

28 U.S.C. 1291 reads in part:

“ The Courts of Appeals shall have jurisdiction of

1 A s to th is confirm ation, the Court’ s attention is directed to the Trial

Court’ s language at the outset o f its order o f Novem ber 5, 1971: “ The

Court having entered its find ings o f fact and con clu s ion s o f law on the

issu e o f segregation on September 27, 1971;”

- A7 -

appeals from all final decisions of the district courts

of the United States . . . ”

If this Court does not deem the Order to be a “ final de

cision” within the meaning of §1291, then the only possible

alternative interpretation is that the Order is interlocutory

and in the nature of an injunction from which appeals are per

mitted pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1292(a) (1):

“ (a) The courts of appeals shall have jurisdiction

of appeals from:

(1) Interlocutory orders of the district courts

of the United States, the United States District

Court for the District of the Canal Zone, the Dis

trict Court of Guam, and the District Court of the

Virgin Islands, or of the judges thereof, granting,

continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving in

junctions, or refusing to dissolve or modify in

junctions, except where a direct review may be

had in the Supreme Court;”

I.

THE ORDER OF NOVEMBER 5, 1971 IS A FINAL

DECISION WITHIN THE MEANING OF 28 U.S.C.

1291 AS THE TERM “ FINAL DECISION” HAS

BEEN INTERPRETED BY THE UNITED STATES

SUPREME COURT, 6TH CIRCUIT AND OTHER

CIRCUITS.

It is ineluctable fact that none of the issues of fact or

law raised in Plaintiffs’ complaint or Defendants’ answer re

main before the Trial Court. All were disposed of by the

“ Ruling on Issue of Segregation” of September 27, 1971, and

the subsequent order incorporating that Ruling on November

5, 1971. All that remains is to fashion a remedy.

- A8 -

These facts, by clear logic and ample precedent, allow

only the conclusion that the above Ruling constitutes a “ final

decision’ ’ within the meaning of §1291, which is appealable

at this time.

With regard to precedent, there is more significance to

the cases Plaintiffs fail to cite than those they do cite.

Plaintiffs’ sole reliance for all practical purposes is on

Taylor v. Board of Education, 288 F. 2d 600 (2d Cir. 1961)

in which the second circuit did hold that an order finding the

existence of de jure segregation and mandating the school

board to submit a desegregation plan was not appealable

either as a final order, or as an interlocutory injunction with

in the meaning of 28 U.S.C. 1292(a) (1). The Taylor decision

is distinguishable from the case at Bar, is not the law of the

Sixth Circuit, has not been followed on this point by any other

Circuit, and most importantly, preceded by approximately 14

months the decision of the United States Supreme Court of

June 26, 1969 in Brown Shoe Company v. United States, 370

U.S. 294, in which the Supreme Court held that an appeal from

an order analagous to the order in the case at Bar must be in

terpreted as a final appealable order.

There has been indication that the Second Circuit’ s posi

tion on this point is not broadly accepted for some time. The

late Mr. Justice Jackson, in reversing another decision of the

Second Circuit which had denied appealability on the grounds

of lack of finality, indicated as much:

“ The only issue presented by this case turns on

the finality of a judgment for purposes of appeal,

a subject on which the volume of judicial writing

already is formidable. The Court of Appeals re

solved against finality of the decree in question,

\ saying, however, that it did so against the unani

mous conviction of the court as constituted but

-AQ-

in deference to a precedent established by a dif

ferently constituted court of the same Circuit,

173 F. 2d 738. Because of this intracircuit con

flict, we made a limited grant of certiorari. 338

U.S. 811. That we cannot devise a form of words

that will settle this recurrent problem seems cer

tain; but in this case we agree with the convic

tions of the court below and reverse its judgment.”

Dickinson v. Petroleum Corporate Conversion

Corporation, 338 U.S. 507, at 508 (1950).

Thus, the Second Circuit itself has long been split on the

question of finality,and the Supreme Court, long ago, became

dubious of the Second Circuit’ s views on finality. This alone

is good reason for this Court not to blindly follow the decision

of a split Second Circuit panel in Taylor.

There is a factual distinction between Taylor and the case

at Bar. As a practical matter, the order in Taylor involved,

basically, desegregating one school in a suburban district.

Here we are speaking of an entire school system, reputedly

the fourth largest school district in terms of student enroll

ment in the United States. Unlike Taylor, leaving the rights

of the parties undetermined now at the appellate level could

result in a great disservice to over 290,000 school children.

Much more on point than the dubious Taylor case is the

more recent pronouncement of the United States Supreme Court

in Brown Shoe Company v. United States, 370 U.S. 294 (1969)

which dictates that the November 5, 1971 order be interpreted

as a final appealable decision.

Brown Shoe Company resulted from a complaint brought by

the United States government alleging that the merger of Brown

Shoe Company and Kinney Shoe Company was in violation of

Section 15 of the Clayton Anti-Trust Act (15 U.S.C. 25). The

District Court held that the Brown-Kinney merger did indeed

- A10 -

violate Section 15 and entered a judgment so concluding, but

reserved ruling on divestiture until the filing of divestiture

plans for doing so. The case reached the United States Supreme

Court by direct appeal pursuant to the so-called Expediting Act,

15 U.S.C.A. Section 29, which permitted direct appeals in the

event of “ final judgment of the district court.”

In holding that the judgment of the District Court could be

interpreted as final, even though no plan for divestiture had

been entered, the United States Supreme Court, speaking through

Mr. Chief Justice Warren, said, beginning at 308:

“ (5) We think the decree of the District Court in

this case had sufficient indicia of finality for us

to hold that the judgment is properly appealable

at this time. We note, first, that the D is tric t

Court disposed of the entire complaint filed by the

Government. Every prayer for re lie f was passed

upon. Full divestiture by Brown of Kinney’ s stock

and assets was expressly required. Appellant was

permanently enjoined from acquiring or having any

further interest in the business, stock or assets of

the other defendant in the suit. The single pro

vision of the judgment by which its f in a lity may be

questioned is the one requiring appellant to pro

pose in the immediate future a plan for carrying

into effect the court’ s order of divestiture. How

ever, when we reach the merits of, and affirm, the

judgment below, the sole remaining task for the

District Court will be its acceptance of a plan for

full divestiture, and the supervision of the plan

so accepted. Further rulings of the District Court

in administering its decree, facilitated by the fact

that the defendants below have been required to

maintain separate books pendente life , are suf

ficiently independent of, and subordinate to, the

issues presented by this appeal to make the case

- A l l -

in its present posture a proper one tor review now.

Appellant here does not attack the full divestiture

ordered by the District Court as such; it is ap

pellant’s contention that under the facts of the

case, as alleged and proved by the Government

no order of divestiture could have been proper.

The propriety of divestiture was considered be

low and is disputed here on an ‘ a ll or nothing’

basis. It is ripe for review now, and w ill, there

after, be foreclosed.

Repetitive judicial consideration of the same

question in a single suit w ill not occur here.

(Citations Omitted)

A second consideration supporting our view is

the character of the decree still to be entered

in this suit. It w ill be an order of fu ll d ives ti

ture. Such an order requires careful, and often

extended, negotiation and formulation. This

process does not take place in a vacuum, but

rather, in a changing market place, in which

buyers and bankers must be found to accom

plish the order of forced sale. The unsettling

influence of uncertainty as to the affirmance of

the initial, underlying decision compelling di

vestiture would only make still more difficult

the task of assuring expeditious enforcement

of the anti-trust laws. The delay in withhold

ing review of any of the issues in the case un

t i l the details of a divestiture had been ap

proved by the D is tric t Court and reviewed here

could well mean a change in market conditions

suffic iently pronounced to render impractical

or otherwise unenforceable the very plan of

asset disposition for which the litiga tion was

held. The public interest, as well as that of

- A12 -

the parties, would lose by such procedure.”

(emphasis added)

The analogy of Brown Shoe Company on the point of issue

here to the case at Bar is clear. That Brown dealt with anti

trust law does not change the fact that it represents the true

state of the law on this issue.

This becomes evident by noting the emphasized portions

of the above quotation and comparing them to the facts in the

instant case. Taken together, the September 27, 1971 Ruling

and Order of November 5, 1971 answered, as in Brown, “ every

prayer for relief” . The Plaintiffs did not prevail on the issue

of segregation among faculty and administration. They pre

vailed on all other issues. As in the Brown case, the only

matter left is the implementation and supervision of a remedy

in accordance with the Trial Court’ s final conclusion on the

issue of segregation. As in the Brown case, if this Court of

Appeals affirms on the merits “ the sole remaining task for the

District Court will be its acceptance of a plan for a full divest

iture, and the supervision of the plan so accepted” . Here it

will be the acceptance and supervision of a desegregation plan.

On the other hand, if this Court finds on appeal that the

Trial Court erred in its Ruling on the Issue of Segregation,

then there will be no need for a remedy.

As was the appellant in Brown, the Board of Education is

in an “ all or nothing” position. The School Board’ s position

is that there should be no order of desegregation just as the

appellant in Brown claimed there should be “ no order of divest

iture” .

As in Brown, there will be no “ repetitive judicial consid

eration” before this Court once this Court decides the basic

segregation issue here which Defendants’ appeal raises.

Just as Mr. Chief Justice Warren in Brown recognized that

a divestiture order is a complicated order demanding time and

consideration because of market conditions, likewise a deseg

regation order by its very nature is complex, not necessarily

because of market conditions, but because of sociological,

economic and changing population patterns which do require

time. As in Brown, a delay here in withholding review will be

contrary to the public’ s interest. If this Court finds no basis

for remedy, then further action on remedy implementation is

futile. If this Court finds that there is a basis for remedy, it

will have established a firm footing for a remedy.

The Trial Court below seemed to merge the concept of de

facto segregation with de jure segregation. The law of the

Sixth Circuit is that a school board is not responsible for de

facto segregation. Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education,

419 F. 2d 1387 (1969). There is also recent indication that the

United States Supreme Court recognizes that the Boards of Edu

cation are not responsible for de facto segregation. See the

Court’ s summary order in Spencer v. Kugler, 40 L.W. 3329

(January 18, 1972).

We recognize that the Trial Court attempted to charge the

Board of Education with de jure segregation, but this attempt

was based on three isolated findings. One suggesting that the

Board had in one instance bussed black pupils past a white

school was not supported on the record for the bussing to the

school involved was for physical facility reasons (newer school)

rather than due to any attempt to segregate. The second finding

concerned the Board’s previous optional attendance zones,

which the Trial Court itself found the Board had actively sought

to eliminate, even hiring an expert to do so. (See page 13 -

Ruling) The third isolated finding was a suggestion that in “ at

least one instance” the Board did build a school “ which con

tains black students” . We suggest that this is indeed an iso

lated instance in a school system of over three hundred school

buildings with over 295,000 school children.

- A14 -

On the other hand, contrary to any other court decision in

which a school board has been charged with de jure segrega

tion, the Trial Court here, in effect, awarded the Board a summa

cum laude degree in its efforts to advance integration. From

page 18 through page 24 of its Ruling, the Trial Court spends

considerable time setting forth the tremendous efforts which the

School Board has expended in an effort to integrate. In fact,

the Court begins its entire discussion at page 18 by the follow

ing words:

“ It would be unfair for us not to recognize

the many fine steps the Board has taken to

advance the cause of quality education for

all in terms of racial integration and human

relations. The most obvious of these is in

the field of faculty integration.”

The issue then is clearly drawn. Do isolated instances

which the Trial Court has properly or improperly found to be

discriminatory form a basis for a finding of de jure student

segregation sufficient to support a comprehensive remedy

when cast against the Trial Court’ s findings that the School

Board has labored mightily to remove de facto segregation?

This crucial issue, if decided in the School Board’s favor,

would be wholly dispositive of the case. If decided adverse

ly to the School Board, it would not be susceptible to reargu

ment in the hearings on proposed remedies. In either event,

it is ripe for decision now.

The key, of course, is the practical interpretation of the

word “ final” . The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit has

traditionally followed an enlightened view in interpreting the

term “ finality” in permitting appeals. Thus, in Gillespie v.

United Steel Corporation, 321 F.2d 518 (1963), this Court

held that a motion striking all references to the statute of the

' State of Ohio, to unseaworthiness, or references to recovery

- A15 -

for the benefit of brothers and sisters of the decedent in an

action for recovery under the Jones Act was an appealable

final order.

In upholding the Sixth Circuit on the issue of finality, the

United States Supreme Court in Gillespie v. United States Steel

Corporation, 379 U.S. 148 at 150 said:

“ Under Section 1291 an appeal may be taken

from any ‘ final order of a district court’ . But

as this court often has pointed out, a decision

‘ final’ within the meaning of Section 1291 does

not necessarily mean the last order possible to

be made in a case . . .

And our cases long have recognized that whether

a ruling is ‘ final’ within the meaning of Section

1291 is frequently so close a question that de

cision of that issue may either be supported

with equally forceful arguments, and that it is

impossible to devise a formula to resolve all

marginal cases coming within might well be

called the twilight zone of finality” .

In a school segregation case, this Court in a short order

denied a motion to dismiss an appeal from an order similar to

the order here, Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga

v. Mapp (filed January 20, 1961).

We appreciate that in Taylor the Circuit Court criticized

this Court’ s decision in Mapp. But then again Taylor was be

fore Brown. We also point out to the Court that although

Taylor was called to the Fifth Circuit’ s attention, the Fifth

Circuit went on to ignore Taylor and held that the ordering of

a desegregation plan dealing expressly with prohibited acts

amounted to a mandatory injunction and was appealable. The

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton, 326

- A16 -

F. 2d 616, 619 (5th Cir. 1964).

The Sixth Circuit has been true to the philosophy of

G illespie as subsequently expressed in Brown in permitting

appeals of final orders such as this including those in school

segregation case. We invite the Court’ s attention to its de

cision in Kelley v. Metropolitan Board of Education, 436 F.

2d 856, 862 (6th Cir. 1970) where the Court upheld the ap

pealability of an order saying “ pupil integration proceedings

for an indefinite time is appealable as a final order under 28

U.S.C. 1291.”

Obviously in Kelley, the Court believed that the matter

should be reviewed by the appellate court because of its im

portance to the parties involved. A similar view was taken

by the Tenth Circuit in Board of Education of Oklahoma City

v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967) where that Court

did not even question its jurisdiction in reviewing an order

requiring a local board to submit a plan with certain specified

features.

The practical approach in a case such as the case at Bar

is to permit the appeals by recognizing that the November 5,

1971 order incorporated the September 27, 1971 ruling as a final

appealable order. All the parties are entitled to know whether

or not the lower court was correct in its decision just as the

Plaintiff was permitted to find out even before trial whether

Public Act 48 was constitutional, Bradley v. M illiken, 443 F.2d

897 (1970), and whether the Trial Court abused its discretion

in not implementing the so-called April 7, 1970 plan. Bradley

v. M illiken, 438 F. 2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971). The only difference

now is that the order is final and it is Defendants seeking re

view.

It should be noted that the Plaintiffs-Appellees have also

filed an appeal challenging the ruling of the Trial Court as to

faculty desegregation. If this Court of Appeals finds that De

fendants’ Board of Education appeal cannot be interpreted as a

final order, the Court still is saddled with Plaintiffs’ appeal.

Since the ruling on that issue denied relief, it is as final a de

cision as is going to be made. There would be no logic to hear

ing only that portion of the case now. Thus, it becomes impera

tive in the interest of judicial economy that all appeals be heard

at this time.

We suggest to the Court that the rights of students are just

as important as the right of corporations which were involved

in the Brown case and for this reason, these appeals should be

heard by this Honorable Court at this time.

II

EVEN IF THIS COURT DECIDES THAT

THE ORDER IS NOT A FINAL ORDER,

IT IS STILL APPEALABLE TO THIS

COURT AS THE COURT HAS JURIS

DICTION UNDER 28 U.S.C. 1292 BE

CAUSE IT HAS TH E EFFECT OF AN

INJUNCTION.

If this Court should interpret the order of November 5,1971

as not a final order that can be appealed under 28 U.S.C. 1291,

it is the position of Defendants’ Board of Education that the

order entered by the District Court on November 5, 1971, is

appealable to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit as a matter of right under 28 U.S.C. §1292 (a) (1).

This statute is the direct descendant of the Evarts Act of

1891, 26 Stat. 828, which was designed to facilitate the appeals

of certain interlocutory orders. The relevant portion of the stat

ute, as currently in force, reads as follows:

“ (a) The courts of appeals shall have jurisdiction

of appeals from:

- A 18 -

(1) Interlocutory orders of the district courts of the

United States, . . . or of the judges thereof, grant

ing, continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving

injunctions, or refusing to dissolve or modify in

junctions, except where a direct review may be had

in the Supreme Court; . . . ”

28U.S.C. §1292 (a) (1).

As interpreted by the courts and academic commentators,

§1292 does not necessarily allow appeals of all orders which

are labeled injunctions, nor does it preclude appeal of orders

which are not labeled injunctions. Here, as elsewhere in the

law, substance rules over form. The consensus of the judicial

and academic authorities seems to be that §1292 permits ap

peals from the granting or denying of injunctive relief when

that relief goes to the heart of the case, and is not merely in

cidental to the trial.

It is clear that the order which Defendant Board of Educa

tion is challenging gives some or all of the substantive relief

sought by a complaint. In fact, it is not too much to say that

the order goes to the heart of the case. The District Court,

after finding against Defendants’ Board of Education on the

issue of de jure segregation, issued this order requiring the

submission of a plan for desegregating the Detroit schools.

The plan ordered is directed precisely to the ultimate relief

sought by Plaintiffs.

Of course, the fact that the November 5, 1971 order was

not stated in terms of prohibition does not affect the fact that

it is an injunction. Mere labels are not decisive in determining

whether an order is an “ injunction” under §1292 (a) (1), and it

is clear that mere words of prohibition are not an essential ele

ment of an injunction. In effect, Defendants’ Board of Educa

tion has been prohibited, with all the sanctions available to the

' District Court, from not submitting a plan. Furthermore, the

- A19 -

Trial Court has enjoined the Board from engaging in any school

construction and this injunction must be interpreted as part of

the November 5, 1971 order.

Thus Courts of Appeals, in other cases involving the de

segregation of schools, have recognized appealability of orders

under §1292 (a) (1). For example, the Fifth Circuit concluded

“ that the ordering of a plan dealing expressly with these pro

hibited acts amounts to a mandatory injunction.” Board of

Public Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616,

619 ( 5th Cir. 1964). The Fifth Circuit has also upheld the

appealability under §1292 (a) (1) of an order “ denying the

plaintiff’ s motion to modify the plan.” Steele v. Board of

Public Instruction of Leon County, 371 F. 2d 395, 396 (5th Cir.

1967). See also Board of Education of Oklahoma C ity v. Dowell,

375 F. 2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967), where the Court did not even dis

cuss the question of its jurisdiction to review a District Court

order requiring a local board to submit a plan with certain speci

fied features.

In all of these cases, the District Court’ s order was held

appealable under §1292 (a) (1). In none of them was the order

stated in prohibitory terms. In each case, the order concerned

the preparation of a desegration plan, and the Courts of Appeals

considered and decided the issues presented on appeal.

Following the lead of the Fifth Circuit and the Tenth Cir

cuit, there is absolutely no reason why this Court of Appeals

could, in the alternative, interpret the order of November 5,

1971 as appealable under Section 1292 (a) (1) as it is in the

nature of an injunction. More importantly, the issue of segre

gation is now ripe for review.

- A 20 -

CONCLUSION

Based upon the reasons set forth above, there is no ques

tion that the order of November 5, 1971 was properly appealed

to this Court and this Court has jurisdiction in the matter as

it was either a final decision within the meaning of 20 U.S.C.

1291 or an interlocutory appealable order within the meaning

of 28 U.S.C. 1292 (a) (1).

Respectfully submitted,

RILEY AND ROUMELL

By: GEORGE T. ROUMELL, JR. / s /

G eorge T. Roum ell, Jr.

Attorneys for Defendants

Board o f Education for the

City o f Detroit, et al

Dated: February 3, 1972

\

- A21 -

APPENDIX J

(Ctjambtra ai

jiltp ljrn 3 . JRoNj

P i X r i r l tub,.

Un it e d St a te s D is t r ic t Co urt

For the Eastern District o r Michigan

Bay City . Michioan. 4«70»

January 25, 1972

Mr. Louis D. Beer

Riley and Roumell

7th Floor Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

RE: Civil Action No. 35257,

Bradley v. Milliken,

_____e t a l .__________________

Dear Mr. Beer:

I have read your letter of January 20th respecting

proposed modifications of the "construction*' injunction

of the court in the above entitled matter. I consider

it better practice in such matters to make a motion

for the amendment of the injunction. I suggest that a

motion be brought for that purpose and that the matter

be noticed for the morning of February 10, 1972, at

any time convenient to counsel. If there is no

opposition, as seems to be the present indication, you

or someone from your office, may simply appear and

present the necessary orders for my signature.

Very truly yours,

SJR:b^g

XC: All counsel of record:

Mr. Lucas

Mr. Ritchie

Mr. Sachs

Mr. Krasicky