Amaker Statement on Mrs. Boynton's Visit to NYC

Press Release

May 14, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 2. Amaker Statement on Mrs. Boynton's Visit to NYC, 1965. a2cb9bf2-b592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/690054d9-fae0-488d-9ef3-10627d977f57/amaker-statement-on-mrs-boyntons-visit-to-nyc. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

aa

c

M

N

a

t

vie

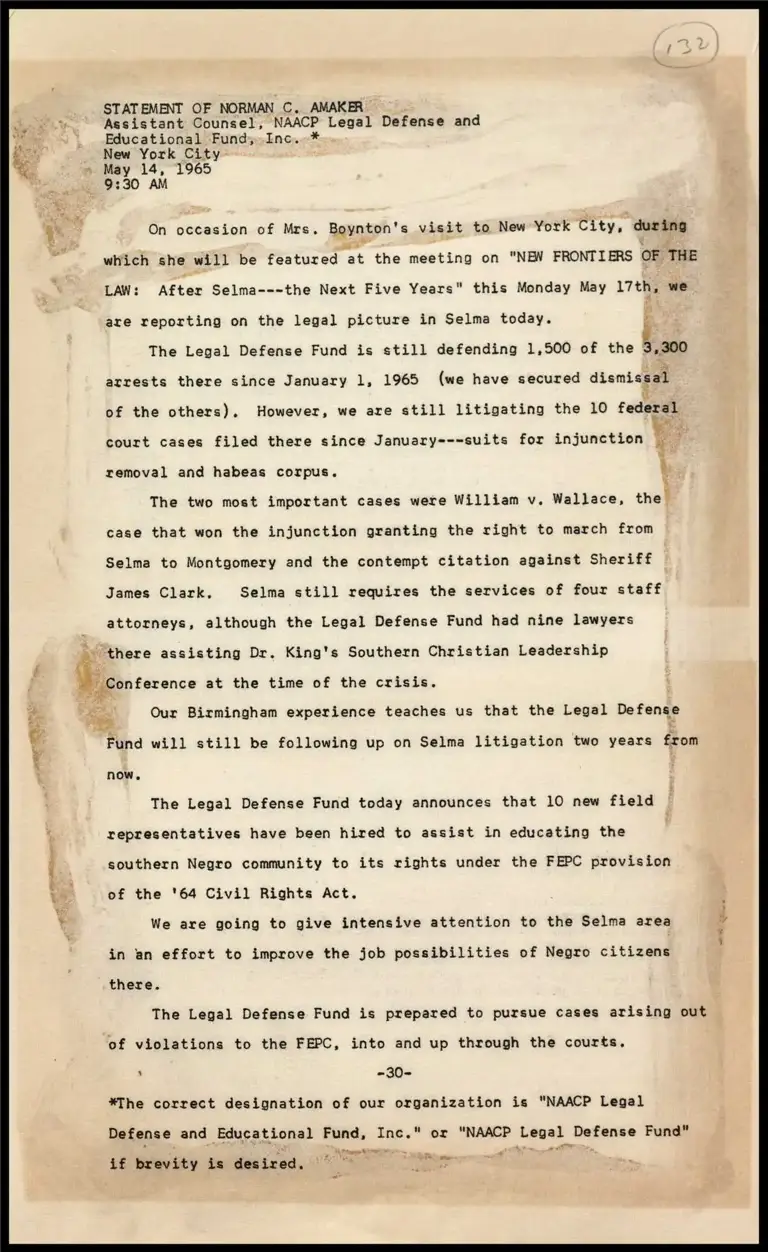

STATEMENT OF NORMAN C._AMAKER

Assistant Counsel, NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund,,Inc..*

New York City

May 14, 1965

9:30 AM

3

On occasion of Mrs. Rgunzen’ s visit to New York City, cue

which she will be featured vat the meeting on "NEW FRONTIERS OF THE

LAW: After Selma---the Next Five Years" this Monday May 17th, we

are reporting on the legal picture in Selma today. 5

The Legal Defense Fund is still defending 1,500 of the Faso

arrests there since January 1, 1965 (we have secured dismissal

of the others). However, we are still litigating the 10 federal

court cases filed there since January---suits for injunction ay

removal and habeas corpus. \

The two most important cases were William v. Wallace, thel

case that won the injunction granting the right to march from

Selma to Montgomery and the contempt citation against Sheriff

James Clark, Selma still requires the services of four staff

attorneys, although the Legal Defense Fund had nine lawyers

‘there assisting Dr. King's Southern Christian Leadership

Conference at the time of the crisis.

Our Birmingham experience teaches us that the Legal Defense

Fund will still be following up on Selma litigation two years from

now,

The Legal Defense Fund today announces that 10 new field f

representatives have been hired to assist in educating the r

southern Negro community to its rights under the FEPC provision

of the '64 Civil Rights Act.

We are going to give intensive attention to the Selma area

in an effort to improve the job possibilities of Negro citizens

there.

The Legal Defense Fund is prepared to pursue cases arising out

of violations to the FEPC, into and up through the courts,

’ nate

*The correct designation of our organization is "NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc." or "NAACP thes Defense Fund"

Sana =

if brevity is desired. eee

me

ng