Rolfe v Lincoln County Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1973

62 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rolfe v Lincoln County Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs Appellees, 1973. 8091f336-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/691a0771-0b81-4370-9128-4f9bc2756445/rolfe-v-lincoln-county-board-of-education-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

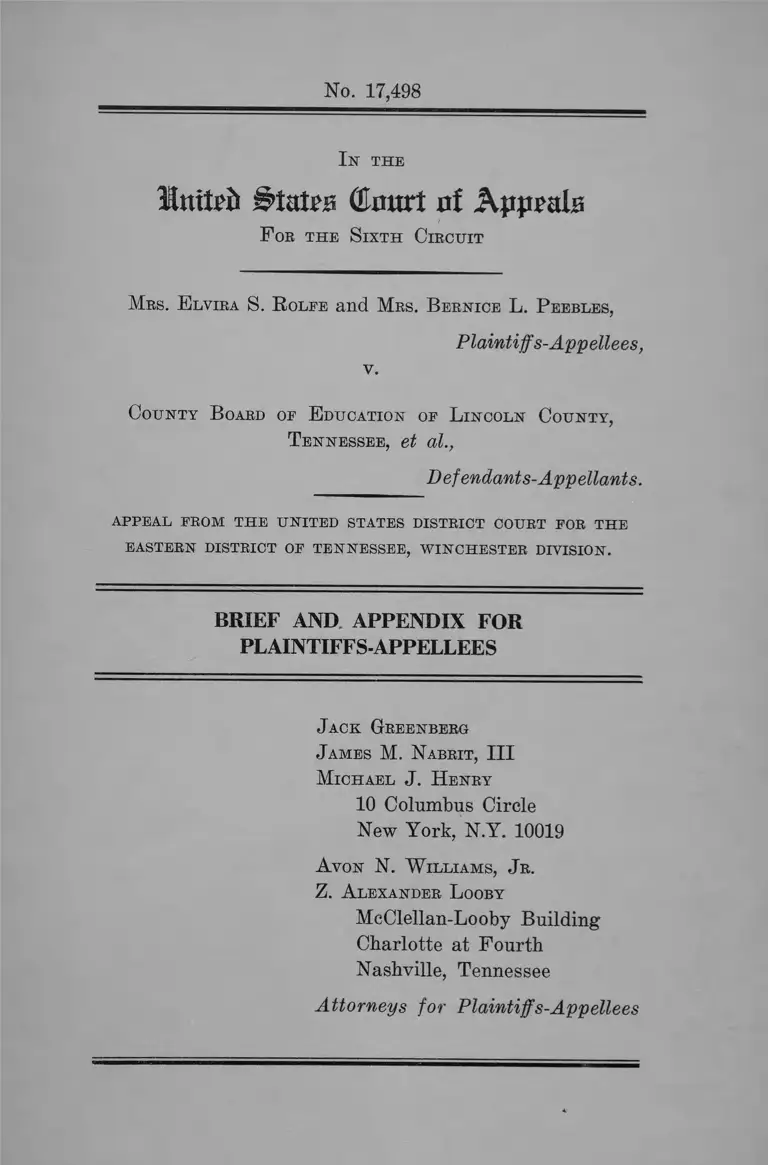

No. 17,498

I n the

llnxUb States Court of Apprala

F oe the Sixth Circuit

Mbs. E lvira S. R olfe and Mrs. B ernice L. P eebles,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

County B oard of E ducation of L incoln County,

T ennessee, et al.,

Def endants-App ellants.

appeal from the united states district court for the

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, WINCHESTER DIVISION.

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael J. H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Counter-Statement of Questions Involved

I.

Was the trial court justified in concluding that Negro

faculty members were wrongfully discharged because of

race, when they had been assigned to an all-Negro school

on the basis of race and were discharged in consequence

of an enrollment loss at that school resulting from the im

plementation of a plan of desegregation, without compari

son to other faculty members in the system?

The District Court answered this question “Yes” and

Appellees agree that it should have been answered “Yes.”

n.

Was the trial court within its allowable discretion in

granting final relief after a hearing on a motion for pre

liminary injunction, where the defendant later offered no

new or different defenses which were not fully litigated

at the initial hearing?

The District Court answered this question “Yes” and

Appellees agree that it should have been answered “Yes.”

III.

Was the trial court justified in concluding that the

defendant board of education had not demonstrated that

wrongfully discharged Negro faculty members failed to

use reasonable efforts to mitigate their damages?

The District Court answered this question “Yes” and

Appellees agree that it should have been answered “Yes.”

IV.

Was the trial court within its allowable discretion in

awarding nominal attorneys’ fees to Negro faculty mem

bers who had been discharged because of race, where there

had been a long history of discriminatory conduct on the

part of the board of education, and the bringing of the

action should have been unnecessary?

The District Court answered this question “Yes” and

Appellees agree that it should have been answered “Yes.”

I N D E X

BRIEF

PAGE

Counter-Statement of Questions Involved.............Prefaced

Counter-Statement of F acts............................................. 1

A. The Issue of Discrimination ................ .......... . 2

B. The Issue of Damages ........................................ 7

Argument ............................................ 10

R elie f.................................................................................... 24

T able oe Cases:

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) .......................... 16

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia,

321 F.2d 494 (4th Cir., 1963) ...................................... 23

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965) .... ......... ...............................................14,17

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 345

F.2d 310 (4th Cir., 1965) ........................................... .14,23

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....15,17

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir., 1966) ......................................14, 22

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Comm’n v. Continental

Air Lines, Inc., 372 U.S. 714 (1963) .... ............ ........ . 17

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) .................. 16

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, 360

F.2d 325 (4th Cir., 1966) ............................... 13,15,17, 22

11

PAGE

International Correspondence School v. Crabtree, 162

Tenn. 70, 34 S.W.2d 447 (1931) .................................. 22

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir., 1966) .......15, 22

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jack-

son, Tenn., 244 F. Supp. 353 (D.C.W.D., Tenn.,

1965) ................................................................................ 23

News Publishing Co. v. Burger, 2 Tenn. Civ. App. 179

(1911) .............................................................................. 22

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ........................ 16

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) .............................. 16

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) .............................. 17

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 186 F.2d 473 (4th

Cir., 1951) ......................................................................... 23

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School Dis

trict No. 32, 365 F.2d 771 (8th Cir., 1966) ____ ____ 16

Smith v. Hampton Training School for Nurses, 360

F.2d 577 (4th Cir., 1966) ................................ 22

State ex rel Anderson v. Brand, 303 U.S. 95 (1938) .... 14

Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee of the Steel

Workers of Chicago, 223 F. Supp. 12 (N.D. 111.,

1963) ............................................................................ 14

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75 (1947) 17

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 346 F.2d

768 (4th Cir., 1965) ....................................................... 15

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952) ................ 14,17

Ill

APPENDIX

PAGE

A ppendix A—

Excerpts from Minutes of Lincoln County Board

of Education Pertaining to School Desegregation

Since 1954 (Exhibit 3) .......................................... . lb

A ppendix B—

Lincoln County Department of Education—Roster

of Teachers 1965-66 (Exhibit 5) ................. ............ 6b

A ppendix C—

Central High School:

Negroes Enrolled—Entrance Dates (Exhibit 13) .. 22b

A ppendix D—

Letter of Discharge—Mrs. Bernice Peebles (Ex

hibit 11) ...................................... 24b

A ppendix E—

Teachers and Students by Race in Each School—

Lincoln County, Tenn. (Exhibit 7) ....................... 25b

A ppendix F —

Interim Earnings—Mrs. Elvira S. Rolfe (Exhibit

19) ........................................................... 26b

A ppendix Gr—

Attempts to Secure Employment—Mrs. Bernice L.

Peebles (Exhibits 17, 20-22) ................................ 27b

I n T he

llnxUh States Court rtf Appeals

F oe the Sixth Circuit

Mbs. E lvira S. R olfe and Mbs. B ernice L. P eebles,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

County B oard of E ducation of L incoln County,

T ennessee, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, WINCHESTER DIVISION.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

Counter-Statement of Facts

This is an action brought by Mrs. Elvira S. Rolfe and

Mrs. Bernice L. Peebles, on behalf of themselves and all

other persons similarly situated, against the County Board

of Education of Lincoln County, Tennessee, seeking relief

against the board’s policy and practice of discriminatory

discharges of Negro teachers.

Although the initial hearing in the case formally con

cerned a motion for temporary restraining order and/or

preliminary injunction, the issues raised by the original

complaint in the case and the motion for temporary re

straining order and/or preliminary injunction were iden

tical (7a-22a). Also, defendants-appellants did not raise

2

any new issues in their answer filed after the initial hear

ing (122a-127a), which were not raised either in their an

swer to the motion for temporary restraining order and/or

preliminary injunction and response to show cause order

(23a-26a) or in the hearing on that motion (26a-107a). At

the conclusion of the hearing on the motion, the Court

asked both parties the following question:

Having heard the proof, do you think the Court now

has the full picture or are we going to have or need to

have an additional trial? In other words, can the evi

dence the Court has now received be the evidence on

trial? (106a-107a).

Defendant-appellants indicated by their silence at that time

that there was no other evidence which they felt should be

heard on the issues in the case, which had not been brought

out in that hearing (107a). As indicated by defendants-

appellants’ own Statement of Facts based on the evidence

heard at the preliminary hearing on the motion, all of the

evidence which could be relevant to the primary issue of

whether plaintiffs-appellees were discharged because of

their race was brought out at that hearing. Thus, it is

inaccurate to suggest that a “ full evidentiary hearing on

the issue of fact” was not held before the Court’s deter

mination of that issue of fact. In its decision, the District

Court concluded that “ the questions involved have now

been briefed well by counsel for the contesting parties and

have been carefully reviewed by the Court” (128a).

A. The Issue of Discrimination

On the merits of the case, the District Court found that

“until the school year 1965-1966, Lincoln County public

schools were operated under a compulsory bi-racial system

in open defiance of the law for nearly a decade” (130a).

3

Referring to the minutes of the Board of Education con

cerning school desegregation (Collective Exhibit 3—re

printed infra, lb-5b), the Court noted that:

Despite urgings for appropriate action in the mean

time, there appears to have been no further discus

sion of desegregation until August 3, 1964; and, as late

as January, 1965, the Board members were still un

able to agree on a plan. The plan was eventually re

arranged in the latter part of April, 1965 to the satis

faction of the Board members and was formally

adopted on May 10, 1965. . . .

It was only when faced with the loss of $136,232.72

in federal aid funds, receipt of which was contingent

on compliance with the Civil Rights Law, that the

defendants adopted a plan of desegregation (130a-

131a).

The evidence at the preliminary hearing showed that

while the Board adopted a desegregation plan (108a-122a)

on May 10, 1965, in order to comply with H.E.W. Guide

lines, the actual intention for the 1965-66 school year was

to continue complete faculty segregation at all-Negro West

End High School and at predominantly white Central High

School, as stated by the superintendent of the school sys

tem, Everett C. Norman (lOOa-lOla). Mr. Norman also ad

mitted that the continuation of faculty segregation could

discourage Negro students from exercising their choices

under a freedom of choice plan to achieve student desegre

gation since they would be jeopardizing the jobs of their

former teachers (98a).

After the plan for desegregation was adopted in the

spring of 1965, Superintendent Norman appeared before

the Negro teachers at West End High School in response

to their inquiries about the effects of the desegregation

4

plan on the faculty. He said at that time that “West End

would he the only school that would he hurt” (34a, 53a).

The Superintendent admitted that he knew that the gen

eral experience has been that no white children transferred

into formerly Negro schools under a freedom of choice

plan (88a). He also admitted that the physical facilities

at West End High School were inferior to those at Central,

and that West End was such a small school as to he educa

tionally inefficient under state standards, so that other

students could not be expected to elect to attend West

End voluntarily (88a-89a). [West End was closed com

pletely the following year (221a).] The Superintendent

also indicated that in the spring of 1965, a general enroll

ment loss composed predominantly of white students was

anticipated for the following fall in Lincoln County and

for that reason fewer new teachers were employed that

summer for the following year than would otherwise have

been (99a).

However, fourteen (14) new teachers were employed for

the 1965-1966 year, all of whom were white (6b-21b). All

the new teachers were hired in the spring or summer of

1965. However, the practice of the Board of Education is

not to actually sign contracts with teachers until the first

pay check is given in the new school year, which is gen

erally two weeks after school begins (85a, 173a-174a).

[This was the point at which plaintiffs-appellees were

notified of their discharge, and were, in fact, discharged.]

Almost all of the enrollment loss which occurred at West

End High School was known to the Superintendent and

the Board on the first day of the new school year (August

23, 1965), since 31 former students at West End registered

on that date at Central High School and the boards of

education of the surrounding counties which had been send

ing Negro students to Lincoln County schools notified the

Lincoln County school system on that date that they would

no longer he doing so, since they were integrating their

own system (81a, 22b-23b).

After the substantial enrollment loss at West End be

came clearly apparent, no comparisons were made of the

qualifications of the now excess Negro teachers at West

End, who had previously been employed by the school sys

tem, with those of the new white teachers, or with any

other teachers (86a). This was in spite of the fact that the

general policy of the Board upon hiring teachers is to com

pare their qualifications with those of all other teachers in

the system rather than just those in one school (94a), and

that teachers are employed by the school system for the

entire system and not for a particular school (93a).

Based on the evidence brought out at the hearing, the

District Court found on the issue of the foreseeability of

the enrollment changes, that back in the spring of 1965,

“ the defendant Mr. Norman and the defendant Board mem

bers were so acutely attuned to the situation that they

were able to anticipate a considerable decrease in enroll

ment system-wide” (131a). The District Court then found

that as soon as the desegregation plan was approved by

H.E.W.,

one week afterward, on September 7, 1965, the de

fendant Board convened in regular monthly session,

and “ * * # reviewed the whole integration problem,

and then it proceeded to take the necessary steps to

correct its teaching load to the amount [sic: number]

of positions it had. # * * ” There were transfers from

one school to another and from one position to another.

No teacher of the Caucasian race was discharged; of

the non-tenure Negro teachers in the system, only one

remained when the Board completed the taking of

“ * # * the necessary steps to correct its teaching

load * * * ” . Four members of the all-Negro faculty

6

at West End were discharged, effective at the end of

the following school day.

Although the defendants contend that teachers are

elected for employment within the system, as opposed

to a particular school, and, although the defendant

Board had provided in its plan of May 10, 1965 that

all teachers would be integrated at the beginning of

the 1965-1966 school year, only members of the West

End faculty were considered for readjustments or dis

charge, and the only comparison of the effectiveness

of the respective teachers in the system was the com

parison of each West End teacher with other West

End teachers.

Considering all non-tenure teachers in the system as

“new applicants” for employment each year, and hav

ing flaunted its own plan by assigning only Negro

teachers to West End School, and in considering only

the comparative qualifications of members of the West

End faculty, obviously, the Board limited its candi

dates for termination of employment to the non-tenure

Negro teachers at West End (133a-134a).

The District Court noted the substantial teaching ex

perience and commendable records of both of the teachers

who are plaintiffs-appellees in this case (132a, 134a-135a),

and concluded that

it is inconceivable to the Court that, had the de

fendants established definite objective standards for

the retention of its teachers and applied those stan

dards to all its teachers alike, without distinction as

to race, that either of these plaintiffs would have suf

fered the loss of her employment. . . .

The professional among the defendants, Mr. Nor

man, concedes that these plaintiffs were well-qualified.

Had this not been true, there could have been no jus

7

tification for their employment and continued re

employment to teach Negro children. But there were

no standards. Except for the protection afforded the

teachers who had attained tenure status under Ten

nessee law, the flexibility was so great that these teach

ers could be hired or fired to accommodate the vacil

lating whims of a majority of the defendant Board

(137a-138a).

# # #

. . . the Court is also struck with the impact of the

lack of good faith exhibited by the defendants in the

purported implementation of its plan [of desegrega

tion], It is reasonable to infer that the defendants

would have continued, in the absence of litigation, to

defy the unambiguous mandate of the law had the

Congress not employed the device of economic sanc

tions to inspire obedience; that the plan eventually

adopted was the minimum which would qualify the

defendants for federal funds; that the bi-parte type of

plan had as its purpose the postponement of assigning

Negro teachers to Central High School; and, that the

plan continued to be the subject of debate until some

ingenious method could be devised to penalize the

Negroes of Lincoln County, locally prominent, through

members of their race who are in the teaching profes

sion, for becoming the beneficiaries of a program of

equalizing the citizenship in this manner (136a).

B. The Issue of Damages

One of the plaintiffs-appellees, Mrs. Peebles, was certi

fied to teach high school mathematics. A new white teacher

was employed by the school system to teach high school

mathematics during the summer of 1965 shortly before

Mrs. Peebles was discharged in September, 1965 (77a, 84a-

85a). Subsequent to her discharge, Mrs. Peebles received

a telephone call from an employee of Superintendent Nor

8

man who said that there was a “possibility” of a job open

ing up, but not that there was actually a position available

at that time (60a). The Superintendent had previously

told Mrs. Peebles that he would contact her when he had

an opening for which she was qualified (61a, 188a). The

nature of the position which in fact eventually developed,

and of which Mrs. Peebles was not notified, was that of a

“visiting teacher,” which is a position more in the nature

of social work than teaching (188a). It did not involve

actual classroom teaching (197a, 220a). Mrs. Peebles later

moved to Huntsville, Alabama, and applied to several dif

ferent schools, and then to several space/defense plants,

which might have utilized her abilities in mathematics, but

was unsuccessful in obtaining employment (61a-62a).

The other plaintiff-appellee, Mrs. Rolfe, held a high

school science teacher’s certificate, as well as an elementary

certificate. There were elementary positions available for

which she could have been considered previous to and at

the time of her discharge (78a). She had brought her

elementary teaching qualifications to the attention of Su

perintendent Norman in the spring of 1965 because she had

thought that due to integration there would be some rear

ranging of faculty, and had been told by him to place the

certificate on file with the appropriate clerk in the Board

of Education office, which she did (102a-104a). The Super

intendent said, however, that he did not remember this

event occurring and was unaware of her elementary quali

fication when she was discharged in September (78a). Al

though Mrs. Rolfe stated in response to the question “Did

you ever apply for a position teaching in elementary schools

in Lincoln County” on cross-examination that she did not

(45a), the bringing to the attention of the Superintendent

of her elementary certificate could have constituted an ap

plication for same as far as he was concerned. Although

Miss Louise Maddox, accountant and personnel clerk of

9

the Lincoln County Board of Education, testified that Mrs.

Rolfe, did not leave her elementary certificate with her

(199a-200a), she also admitted that she dealt with a very

large number of records of teachers, that Mrs. Rolfe came

to the office and took her own records away after her dis

charge, and that she had no way of knowing, apart from

her personal recollections of one year previously, as to

whether there had actually been an elementary certificate

on file or not (203a-208a). Upon returning home to Nash

ville after her discharge, Mrs. Rolfe applied to the Board

of Education there for a teaching position, and to the Head

Start program, the Study Center, and a hospital, but was

unable to secure other than temporary employment as a

substitute teacher and a hospital attendant (47a-48a). Al

though each plaintiff-appellee moved out of town, their

current addresses were always known to the Board of

Education.

The subsequent hearing in the case, held on August 26,

1966 was confined to the issue of damages, since the Court

determined that sufficient evidence had already been in

troduced on the primary issue of whether the discharges

were in consequence of racial segregation (128a-139a). Al

though defendants-appellants made an offer of proof dur

ing that hearing concerning the primary issue (172a-180a),

which was refused, virtually all of the elements of that

offer of proof had previously been introduced in the earlier

hearing which led to the determination of the primary is

sue (65a-101a).

The Court was not convinced at the hearing on dam

ages that any of the evidence put forward by defendants-

appellants made out a case in mitigation, and therefore

since the burden of proof in mitigation was on the de

fendants-appellants, awarded full damages to both plain

tiff s-appellees (less their interim earnings) (191a, 238a-

241a).

10

A R G U M E N T

I.

Was the trial court justified in concluding that

Negro faculty members were wrongfully discharged

because of race, when they had been assigned to an

all-Negro school on the basis of race and were dis

charged in consequence of an enrollment loss at that

school resulting from the implementation of a plan

of desegregation, without comparison to other faculty

members in the system?

The District Court answered this question “ Yes”

and Appellees agree that it should have been answered

“ Yes.”

In this case, a board of education which was implement

ing a Constitutionally required plan of desegregation, uti

lizing the “ freedom of choice” approach, discharged the

non-tenure Negro teachers at the previously all-Negro

school upon a substantial drop in enrollment at that school

—without comparing the qualifications of the discharged

teachers to other non-tenure teachers in the system, and

shortly after employing fourteen new white teachers for

the system. The plan of desegregation was adopted in the

spring of 1965, under the impetus of a threatened with

drawal of federal funds under Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 if such a plan of desegregation was not adopted

(130a-131a). Under the requirements of Tennessee law, the

board of education “ elects” the teachers it believes will be

needed in the following year 30 days before the expiration

of the current school year (134a). When this was done in

the spring of 1965, the board assigned an all-Negro faculty

to the all-Negro school (West End) which was to be incor

11

porated in the plan of desegregation for the following year

(134a). At approximately this time, the Superintendent

(Mr. Norman) appeared before the faculty members at

West End and said that he anticipated that West End

would be the only school which would be “hurt” by the plan

of desegregation with regard to faculty positions (134a).

The Superintendent and the board were so acutely attuned

to the situation that they were able to anticipate a consider

able system-wide enrollment decrease the following fall, and

so employed fewer new teachers at that time than they

would otherwise have done (131a). They were also aware

that white students generally do not transfer to previously

all-Negro schools under “ freedom of choice” plans of de

segregation, so that an enrollment loss could be anticipated

at West End (88a).

When the substantial enrollment loss actually material

ized at West End during the first week of the 1965-66 school

year in August 1965, the non-tenure Negro teachers there

were discharged, without comparison to the qualifications

of the other non-tenure teachers in the system, including

those white teachers with less seniority who had just been

employed by the system (134a-135a). This was in spite of

the facts that the policy of the school system is to employ

teachers for the system rather than for a particular school

(133a), that teachers are compared with all other teachers

in the system as to effectiveness before they are “re-elected”

each spring (134a), and that the general practice of the

system was not to sign contracts with non-tenure teachers

until two weeks after the school year began (85a, 173a-

174a).

Plaintiff Mrs. Eolfe had six years’ experience elsewhere

and two years’ experience in the Lincoln County system,

and Plaintiff Mrs. Peebles had two years’ experience else

where and two years’ experience in the Lincoln County

system (132a). The District Court noted:

12

Mr. Norman conceded that there are non-tenure

teachers in the elementary schools of Lincoln County

with less qualifications than those possessed by Mrs.

Rolfe. Eight such teachers were junior to Mrs. Rolfe

in point of service with the system. She, however,

was the junior science instructor in the system. He

could not compare the qualifications of Mrs. Peebles

with other mathematics instructors in the system, and

asserted, despite all the foregoing, that he could not

foresee the subsequent abolishment of Mrs. Peebles’

position at West End when he engaged, less than a

month earlier, a newcomer to the system to teach solid

geometry, trigonometry and algebra I at Central High

School.

The aforementioned “newcomer” soon resigned, and

the qualifications of Mrs. Peebles were considered

against those of Mrs. Martha Crawford, a former

teacher there who had left the system until “ a home

situation cleared up” . The two teachers were com

pared carefully and at length, and the Board decided

that Mrs. Crawford’s qualifications “ # * # were a little

better * * * ” than Mrs. Peebles’. Included in the com

parison was the fact that Mrs. Crawford had passed

one course in calculus which Mrs. Peebles had been

required to repeat several times in college, although

Central High School has never offered, and does not

now offer, calculus (134a-135a).

# #

Both Mrs. Rolfe and Mrs. Peebles had been compli

mented in their respective work at West End by the

principal. Neither had ever received any reprimand

or complaint about their performance of their respec

tive assignments (135a).

13

After a review of the qualifications of the non-tenure

teachers in the system, the District Court concluded:

It is inconceivable to the Court that, had the defen

dants established definite objective standards for the

retention of its teachers and applied those standards

to all its teachers alike, without distinction as to race,

that either of these plaintiffs would have suffered the

loss of her employment. The Court does not insist

that seniority should be the determining factor in de

ciding who shall go and who shall remain, but in the

ordinary habits of life, the Court does believe that,

had two persons been equated on the same standards,

the more junior is the more likely to leave (137a-138a).

# # * ___

The defendants admit, in part, their bad faith, i.e.,

they promulgated a plan providing for the immediate

integration of their faculties when it was their stated

purpose to maintain segregated faculties in the two

principal schools in Fayetteville. They failed to es

tablish definite objective standards for the employment

and retention of teachers for application to all teachers

alike; instead, they designed a pattern which could

only result in discrimination against Negro teachers

(136a-137a).

The District Court’s decision is clearly in accord with the

now unarguable proposition that Negro faculty members

assigned to Negro schools on the basis of race may not be

dismissed in consequence of enrollment losses resulting

from the implementation of plans of desegregation, without

comparison to other faculty members in the system, since

such dismissals are clearly on the basis of race. In Frank

lin v. County School Board of Giles County (Va.), 360 F.2d

325 (4th Cir., 1966), the school board simply closed the

14

Negro schools, allowing all of the Negro children to trans

fer to the formerly white schools, but discharging all of the

Negro faculty members. The Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit held that on the record in the case, no com

parative evaluation of the discharged teachers with the

other teachers in the system had apparently been made,

even though teachers were employed for service to the sys

tem rather for a particular school, and that therefore “ the

plaintiffs were discharged because of their race.” 360 F.2d

at 327. The Court said:

The defendants have conceded that the Fourteenth

Amendment forbids discrimination on account of race

by a public school system with respect to the employ

ment of teachers. Bradley v. School Board, 345 F.2d

310, 316 (4 Cir. 1965), reversed on other grounds, 382

U.S. 103 (1965).

Under the circumstances, the plaintiffs are entitled

to a mandatory injunction requiring their reinstate

ment. See: State ex rel Anderson v. Brand, 303 U.S.

95 (1938); Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952);

Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee of the Steel

Workers of Chicago, 223 F.Supp. 12 (N.D. 111. 1963).

We think the provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

(42 U.S.C. § 2000 e-5(g)) where the courts are granted

authority to order reinstatement of discriminitees fur

ther supports our conclusion. 360 F.2d at 327.

In Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education

(N. Car.), 364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir., 1966), at the end of a

school year the Negro enrollment in the system dropped

by 50% because Negro students who had attended the city

schools from adjoining counties were integrated into their

respective county schools, and the city board of education

then integrated its remaining Negro students into its

15

system, thereby reducing the number of teaching positions

by five. Of the 24 Negro teachers in the system, only

8 were offered re-employment for the following year,

although every white teacher who indicated the desire was

re-employed together with 14 new white teachers, all with

out previous experience. All of the Negro teachers were

required to stand comparison not only with all of the other

teachers previously in the system, but with all of the new

white applicants, before retaining their jobs, while none

of the white teachers was subjected to this test. The

Fourth Circuit said:

Patent upon the face of this record is the erroneous

premise that when the 217 Negro pupils departed

and the all Negro consolidated school was abolished,

the Negro teachers lost their jobs and that they, there

fore, stood in the position of new applicants. The

Board’s conduct involved four errors of law. First,

the mandate of Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954), forbids the consideration of race in

faculty selection just as it forbids it in pupil place

ment. See Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Educa

tion, 346 F.2d 768, 773 (4 Cir. 1965). Thus the reduc

tion in the number of Negro pupils did not justify a

corresponding reduction in the number of Negro teach

ers. Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

360 F.2d 325 (4 Cir. 1966). Second, the Negro school

teachers were public employes who could not be dis

criminated against on account of their race with respect

to their retention in the . system. Johnson v. Branch,

364 F.2d 177 (4 Cir. 1966), and cases therein cited,

wherein the court discussed the North Carolina law

respecting teacher contracts and the right of renewal.

White teachers who met the minimum standards and

desired to retain their jobs were not required to stand

comparison with new applicants or with other teachers

16

in the system. Consequently the Negro teachers who

desired to remain should not have been put to such

a test. 364 F.2d at 192.

* # *

Finally, the test itself was too subjective to with

stand scrutiny in the face of the long history of racial

discrimination in the community and the failure of the

public school system to desegregate in compliance with

the mandate of Brown until forced to do so by litiga

tion. In this background, the sudden disproportionate

decimation in the ranks of the Negro teachers did raise

an inference of discrimination which thrust upon the

School Board the burden of justifying its conduct by

clear and convincing evidence. Innumerable cases have

clearly established the principle that under circum

stances such as this where a history of racial discrimi

nation exists, the burden of proof has been thrown upon

the party having the power to produce the facts. In the

field of jury discrimination see: Eubanks v. Louisiana,

356 U.S. 584 (1958); Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85

(1955); Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953); Norris

v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935). 364 F.2d at 192-193.

In Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School

District No. 32 (Ark.), 365 F.2d 771 (8th Cir., 1966), the

school board “ re-elected” the Negro faculty members to

the Negro school but without signing contracts with them

at that time, and also adopted a “freedom of choice” de

segregation plan at about the same time for compliance

with the Civil Bights Act of 1964. Upon ascertaining that

the enrollment was going to drop precipitously at the Negro

school, the board decided to close the Negro school alto

gether and completely integrate the system, and then in

formed all of the Negro teachers at the Negro school

that their jobs were abolished. Shortly thereafter, 13

17

teachers resigned or retired during the course of the sum

mer, and 14 new teachers were hired, 12 of whom were

white. The Board said that it simply applied its traditional

policy in cases of the closing of schools due to consolida

tion, namely, to absorb the teachers of the closed school

into the remaining schools if this could be done without

displacement of other teachers, and, if not, to dismiss the

former. The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit said:

It is our firm conclusion that the reach of the Brown

decisions, although they specifically concerned only

pupil discrimination, clearly extends to the proscrip

tion of the employment and assignment of public school

teachers on a racial basis. Cf. United Public Workers

v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75, 100, 67 S.Ct. 556, 91 L.Ed. 754

(1947); Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183, 191-192,

73 S.Ct. 215, 97 L.Ed. 216 (1952). See Colorado Anti-

Discrimination Comm’n v. Continental Air Lines, Inc.,

372 U.S. 714, 721, 83 S.Ct. 1022, 10 L.Ed.2d 84 (1963).

This is particularly evident from the Supreme Court’s

positive indications that nondiscriminatory allocation

of faculty is indispensable to the validity of a desegre

gation plan. Bradley v. School Board, supra; Rogers

v. Paul, supra. . . .

We recognize the force of the Board’s position

that the discharge of the Sullivan staff upon the

school’s closing was only consistent with the action

taken by the Board in connection with eleven other

school consolidations, and consequent closings, in the

past. This stands in contrast to the past practice

noted in Franklin v. County School Bd., supra, p. 326

of 360 F.2d. And we need not now determine whether

across-the-board staff dismissals in the absence of

vacancies when a school is closed, and the failure

comparatively to evaluate the qualifications of those

18

dismissed with the qualifications of those retained,

standing alone and apart from racial considerations,

amount to an unconstitutional selection method. .

But on this record these dismissals do not stand

alone. This Board maintained a segregated school

system for more than a decade after its unconstitu

tionality was known and before it implemented a plan

to desegregate. The employment and assignment of

teachers during this period were based on race. . . .

The use of the freedom-of-choice plan, associated with

the fact of a new high school plant, produced a result

which the superintendent must have anticipated, de

spite his testimony that he “ rather guessed” that Sulli

van would continue to operate; . . . All this reveals

that the Sullivan teachers did indeed owe their dis

missals in a very real sense to improper racial consid

erations. The dismissals were a foreseeable conse

quence of the Board’s somewhat belated effort to bring

the school system into conformity with constitutional

principles as enunciated by the Supreme Court of the

United States. 365 F.2d at 778-779.

19

II.

Was the trial court within its allowable discretion in

granting final relief after a hearing on a motion for

preliminary injunction, where the defendant later of

fered no new or different defenses which were not

fully litigated at the initial hearing?

The District Court answered this question “ Yes”

and Appellees agree that it should have been answered

“ Yes.”

The motion for temporary restraining order and/or

preliminary injunction (21a-22a) raised the same issues

as the original complaint (7a-21a). After a full hearing

(26a-121a) on the motion in which defendants-appellants

were able to offer all of the evidence which they thought

relevant to the issues in the case, the trial court asked the

parties if they would be satisfied to consider the hearing

on the motion as the trial on the merits (107a). Defendants-

appellants gave no indication at that time that, they were

dissatisfied with that hearing as a trial on the merits (107a).

In their subsequent answer filed after the initial hearing

(122a-127a), defendants-appellants did not offer any new

defenses which had not been contained in their answer to

the motion and response to show cause order (23a-26a)

or which were not offered in the initial hearing (26a-121a).

Both sides then thoroughly briefed the law and the evi

dence as it had been introduced at the initial hearing

(128a), and the district court then made an adverse de

termination to defendants-appellants on the primary issue

of whether the Negro faculty members were discharged

because of race, and limited the subsequent hearing to the

issue of damages (128a-139a).

It was only after this adverse determination that defen

dants-appellants began to complain that they had not had

20

their full day in court on the issue of racial motivation in

the discharges of plaintiffs-appellees (151a). At the sub

sequent hearing on the issue of damages, defendants-

appellants made an offer of proof (172a-180a) on the

issue of racial motivation, which was rejected by the trial

court (169a-172a). This offer of proof consisted only of

the testimony of the Superintendent of Schools of Lincoln

County, Everett C. Norman, who had previously testified

at length (65a-101a) in the earlier hearing- which led to

the adverse determination, and did not contain any new

relevant evidence which had not been previously intro

duced before the adverse determination.

Thus by their failure to indicate any new evidence which

should have been considered on the issue of whether the

Negro faculty members were discharged because of race,

defendants-appellants have clearly demonstrated that they

had their full day in court. In its normal supervisory role

of limiting the litigation in federal courts to those pro

ceedings which are really necessary to resolve disputed

issues, the district court was clearly within its allowable

discretion in concluding that a sufficient hearing on the

merits had been held.

21

III.

Was the trial court justified in concluding that the

defendant board of education had not demonstrated

that wrongfully discharged Negro faculty members failed

to use reasonable efforts to mitigate their damages?

The District Court answered this question “ Yes”

and Appellees agree that it should have been answered

“ Yes.”

The board of education attempted to show that Mrs.

Eolfe had not brought her elementary certificate to the

attention of the Superintendent of Schools, Mr. Norman,

and placed it on file in the superintendent’s office, as she

said she had (102a-104a). However, the testimony of Louise

Maddox, a clerk in the superintendent’s office, that Mrs.

Eolfe had never left her elementary certificate there while

she was employed by the school system, was thoroughly

vitiated by her admissions that she dealt with the records

of a large number of teachers, that the events in issue

were a whole year previous to the time of the hearing,

that Mrs. Eolfe had taken her records away from the office

after her discharge, and that Miss Maddox had no way of

knowing apart from her personal recollections that there

had not been an elementary certificate on file (203a-208a).

After moving to Nashville following her discharge, Mrs.

Eolfe attempted to secure a number of different positions,

but was unsuccessful in obtaining anything other than

temporary employment (47a-48a).

The board of education attempted to show that it subse

quently offered Mrs. Peebles a position similar to the one

from which she was discharged, but the position was in

fact that of a “visiting teacher” which is more similar to

social work and involves no classroom teaching (188a,

22

197a, 220a), and Mrs. Peebles was certified as a high school

mathematics teacher. Also, the Superintendent never

called her and told her that there was a position avail

able, as he had promised to do (61a, 188a, 24b). An em

ployee in his office simply called earlier and said there was

a “possibility” of a position becoming available (60a).

After moving to Huntsville, Alabama, Mrs. Peebles at

tempted to secure a number of different positions, but

was unsuccessful in obtaining any employment (61a-62a,

27b-30b). She applied to individual schools in the Hunts

ville area rather than to the board of education office be

cause she had been informed that it was the individual

principals in the system who did the hiring (61a-62a).

The District Court having held the discharges of plain

tiffs unconstitutional, it is clear that they were entitled to

damages. Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Ed

ucation, supra; Johnson v. Branch, supra; Franklin v.

County School Board of Giles County, supra; Smith v.

Hampton Training School for Nurses, 360 F.2d 577 (4th

Cir., 1966). The proper measure of damages is the amount

of pay which plaintiffs would have earned during the

period from date of discharge to date of reinstatement,

diminished by earnings in the interim during the school

year. Smith v. Hampton Training School, supra. The

Tennessee rule is that the defendants have the burden of

proof in establishing matters asserted by them in mitiga

tion or reduction of the amount of damages. International

Correspondence School v. Crabtree, 162 Tenn. 70, 34 S.W.

2d 447 (1931). Furthermore, the duty of an employee who

is wrongfully discharged to minimize damages does not

require such employee to take employment of an inferior

or different nature, or to leave home and go to a distant

place in order to obtain such employment. News Publish

ing Co. v. Burger, 2 Tenn. Civ. App. 179 (1911). The Dis

trict Court’s determination that wrongfully discharged

23

Negro faculty members had used reasonable efforts to

mitigate their damages was clearly in accord with the

applicable law.

IV.

Was the trial court within its allowable discretion in

awarding nominal attorneys’ fees to Negro faculty mem

bers who had been discharged because of race, where

there had been a long history of discriminatory con

duct on the part of the board of education, and the

bringing of the action should have been unnecessary?

The District Court answered this question “ Yes”

and Appellees agree that it should have been answered

“ Yes.”

The District Court said:

It has heretofore been found by the Court that the

defendants have been guilty of “ * * * a long-continued

pattern of evasion and obstruction * * * ” of the de

segregation of the public schools system of Lincoln

County, Tennessee. In such event counsel fees are

allowable, and disallowance of such fees is an abuse of

judicial discretion (239a).

This is clearly in accord with the applicable law. Bell v.

School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, 321 F.2d 494

(4th Cir., 1963); Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of

the City of Jackson, Tenn., 244 F.Supp. 353 (D.C.W.D.,

Tenn., 1965); Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 186

F.2d 473 (4th Cir., 1951); Bradley v. School Board of the

City of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir., 1965) ; 6 Moore’s

Federal Practice (2nd Ed.) 1349, 1352. It should be noted

that the amount of attorneys’ fees awarded ($250) is

nominal, considering the amount of effort which had to

be expended in such a complex case.

24

Relief

For the foregoing reasons, the Appellees contend that

the judgments of the District Court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

M ichael J. H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

APPENDIX

APPENDIX A

Excerpts from Minutes of Lincoln County Board of Ed

ucation Pertaining to School Desegregation Since 1954

(Exhibit 3)

June 24, 1955—The Board discussed but took no action on

a letter received from the State Commissioner of Educa

tion relative to Supreme Court decision on school inte

gration.

August 15, 1955—Motion by Heed second by Jennings that

in view of much consideration on the subject of integration

that we, hereby, go on record as adopting a plan to be

known as the Free Choice Plan of school attendance for

negro and white children in Lincoln County, to take effect

with the school year 1956-57 embodying the principles

suggested by this name and instruct the Superintendent

of Education to proceed immediately to work out the de

tails of this plan for presentation to this Board at the

earliest practical time. Motion carried.”

April 12, 1956—Prof. Lemons appeared before the Board

to present a discussion on school consolidation for the

negro schools of Lincoln County. He pointed out that his

presentation would include the following three points:

1. County wide consolidation of negro schools

2. Promotion of good race relations.

3. A savings to the tax payers.

He further pointed out that they are 557 negro students

in Lincoln County and that consolidation would provide

for all (1) hot lunches, (2) central heating, (3) inside toilet

lb

2b

facilities (4) conserve teachers and (5) provide a more

complete curriculum. This, if accomplished, would continue

race relations on the present high levels. Integration would

not necessarily be a forced issue. Prof. Lemons asked if

the Board if they would like to have the above presenta

tion in written form. The Chairman informed that the

Board desired such a written plan and thanked him.”

March 8, 1961—Prof. Lemons and Prof. Curtis appeared

before the Board with long-range plan for consolidating

all county and city Negro schools. No action was taken.

Further study was recommended. It was decided to wait

for legislative action pending General Assembly. Attached

is a copy of their plan.

August 3, 1964—The policy on Civil Bights was discussed.

Mr. Norman read a letter from Commissioner Warf, con

cerning this law. Action was deferred for the moment.

The Civil Bights discussion was reopened. Mr. Hodges

read the present policy on the admission of pupils to

schools. The Chairman asked Mr. Hodges to amend the

present policy to comply with the Civil Bights Law and

to read it to the Board as amended.

Motion by Hodges second by Fowler that policy no. 5111

be amended and adopted as follows:

“ B equibements eob A dmission to L incoln County

S chools Gbades 1-12 I ncluding the M in im u m A ge

fob the A dmission of P upils”

Any child residing within Lincoln County, Tennessee and

who has attained the age of six (6) years on or before

December 31st following the beginning of the school term

Appendix A

3b

may enter at the beginning of the school year, any public

school within the school district in which he resides.

This policy shall be administered in compliance with Title

VI of the Civil Eights Act of 1964.

Motion carried.

Dec. 7, 1964—Mr. Norman reported on the Human Rela

tions in Nashville. About 600 people from all fields of

business, attended. Mr. Norman quoted Mabel Martin, a

negro lawyer, who had discussed at length, the Civil Eights

Law in respect to schools. The basic point of the whole

discussion seemed to be that every school in Tennessee

must have a plan for integration by next school year and

it must be implemented as soon as possible. Each county

will be responsible for its own plan.

Mr. Hodges suggested we write Congressman Evins for a

copy of Title VI also a copy of the executive order to the

Justice Department, the Civil Eights Commission, and

Health, Education and Welfare on the Implementation of

the Act.

January 4, 1965—Mr. Norman reported that a map of the

county is being made to show the location of each negro

child. He also that Miss McAfee had made a survey of

the Negro Classroom instruction and that she had said

the negro instructors were on an average with the white

instructors. These things have been done in preparation

for making a plan for integration.

January 15, 1965—Mr. Norman stated the purpose of this

meeting is to get a plan of integration made and into

the hands of the Commissioner. No contracts can be signed

for Federal Funds after January 3, 1965 until such time

Ap-pendix A

4b

as the plan is received by the Commissioner. Mr. Norman

stated the three alternatives as given by the Commissioner

as follows:

1. Sign a “Plan of Assurance” of making a plan for

abiding by the regulations;

2. Make a plan and mail it to Washington for ap

proval; or

3. Operate under a court order.

Mr. Norman stated he thought the first plan was the most

feasible. He read the “Plan of Assurance” to the Board.

The steps to take are: (1) Sign the Plan of Assurance,

(2) Publish intent of complying, and (3) Put the plan into

action.

There was a long discussion on each of the three alterna

tives. The motion was made by Mr. Smith and seconded

by Mr. Erwin that the Assurance of Compliance be signed

to-night (Jan. 15) Vote: 4 yes, 4 no. Motion dead.

The motion was then made by Mr. Porter and seconded

by Mr. Pendergrass that discussion on the motion be de

ferred until the next meeting, a study be made and that

action be taken at that time. Motion carried. The meeting

date was set for January 25.

January 25, 1965— Special session. Superintendent read

the Assurance Agreement with the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare for the benefit of those who were

not present at the last meeting. Mr. Erwin moved that the

Board comply with the signing of the Assurance agree

ment of Title VI of the new Civil Rights Law. Mr. Taft

seconded. Vote: 4 yes, 4 no. No action.

Appendix A

5b

Mr. Hodges moved that a certified copy of the Board min

utes of Aug. 3, 1964 be sent to the Commissioner of Edu

cation and a plan of total system improvement be pre

sented at the next regular meeting of the Board for their

consideration, one element of the plan being to comply

with Title VI of the Civil Bights Law. Mr. Pendergrass

seconded. Vote : 4 yes, 4 no. No action.

Mr. Hodges then moved that the resolution already on

the minutes of the Board (August 3, 1964) serve as official

implementation for the signing of Assurance of Compli

ance with the Health, Education and Welfare Begulation

under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Mr. Porter

seconded. This motion carried, unanimously.

Feb. 8, 1965—Motion by Erwin second by Smith that an

integrated supper for safety promotion be planned by Mr.

Sowell for bus drivers and Board members. Motion carried.

May 10, 1965—Mr. Norman read the Amended Plan for

Compliance with the Civil Bights Law. Motion by Smith

second by Fowler that the amended plan be adopted to

supersede all other plans. Motion carried.

Appendix A

A

P

P

E

N

D

IX

B

Lincoln County Department of Education — Roster of Teachers 1965-66

(Exhibit 5)

Name of Teacher

Education

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Bate of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Rachel Jean W 4 Years 27 Years Perm

W orld H istory, Librarian,

Mathematics 7 & 8 Blanche

Lucille H all W 4 Years 32 Years Perm

English 9 & 11,

General Business Blanche

Ellen Jobe W 2 Years 26 Years Grade 3 Blanche

Stanley Mullins w 4 Years 8 Years Perm

A lgebra 1 & 2, B iology,

Arithm etic 9 Blanche

Frances W atson w 4 Years 38 Years Perm Grade 2 Blanche

M ildred Twitty w 4 Years 27 Years Perm

Shorthand, Bookkeeping,

T yping 1 & 2 Blanche

Eva Groce w 4 Years 19 Years Perm Grade 1 Blanche

W ayne M oore w 4 Years 5 Years

2 Y r

Prob

English 10 & 12,

Language A rts 7 Blanche

M arilyn M cDonald N 3 Years 2 Years

2 Y r

P rob Grades 4 & 5 Comb. Blanche

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education Sp

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Delton Ashby W 4 Years 2 Years

2 Y r

Prob Grades 5 & 6 Comb. Blanche

Janice Smith W 3 Years 1 Year

1 Y r

Prob

Social Studies & P. E.,

Language A rts 7 & 8 Blanche

L arry Burks W 4 Years 10 Years

3 Y r

Prob

Adm inistration

Athletic Coach Blanche

Larry Patterson W 2 Years 0 Years P rob

Am erican History,

P E (B oys & Girls) Blanche A u g 2, 1965

Drusilla Nosson W 4 Years 23 Years Perm

General Science, Chemistry,

Y oc. H om e Ec. Blanche

Thomas Mann W 4 Years 14 Years

2 Y r

P rob

Science 7, Vocational

Agriculture Blanche

B u ford Beadle W 5 Years 17 Years Perm

Adm inistration, Advanced

Math, P E (G irls) Boonshill H

Kathleen W elch W 4 Years 29 Years Perm Grade 5 Boonshill E

Doris Zeigler W 4 Years 19 Years Perm Grades 1 & 2 Boonshill E

June M cK inney W 4 Years 17 Years Perm Grade 4 Boonshill E

M argaret Sullivan w 5 Years 17 Years Perm

H istory 8, Spanish,

English 7, Librarian Boonshill H

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Bace

Education

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Paul M cK inney W 3 Years 3 Years

3 Y r

P rob Grade 6 Boonshill E

Marie M edley W 4 Years 9 Years Perm Grades 2 & 3 Boonshill E

Tyrone Ingram W 4 Years 2 Years

2 Y r

P rob

Math 7 & 8, A lgebra I,

W orld H istory, Health Boonshill H

Carolyn Foster W 4 Years 3 Years

2 Y r

P rob

English 9, Typing,

Shorthand Boonshill H

Phillip Thomson W 5 Years 9 Years Perm

A lgebra I I , B iology,

Chemistry, Science 8 Boonshill H

Bra G. Templeton W 4 Years 4 Years Perm

English 8, Science 7,

H om e Econom ics Boonshill H

Gerth Alexander W 5 Years 21 Years Perm

General Science

V oc. Agriculture Boonshill H

Nancy W ilson W 4 Years 2 Years Prob

English

Am erican H istory Boonshill H Aug. 20, 1965

H ilda Smith W 4 Years 2 Years Prob

English

Am erican H istory Boonshill H Oct. 4, 1965

Leonard Mansfield w 4 Years 29 Years Perm Supervising Principal Central H

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Education # Length of Date of Employ-

Qualifica- Employ- Tenure Assigned ment (new

Name of Teacher Mace tions ment Status Nature of Subjects Taught__School______________ teachers)___iv a m e o j 1 e a r n e r

Charles Linsday

jtcace

w 4 Years 36 Years Perm

Science I

Assistant Principal Central H

Ruth M cCown w 4 Years 33 Years Perm Guidance Counselor Central H

Pauline Burton w 4 Years 29 Years Perm

W orld H istory

Bookkeeping Central H

K ent R ay w 4 Years 26 Years Perm

Latin I & II ,

Plane Geometry Central H

Bernice Matcher w 4 Years 18 Years Perm English I & I I I Central H

Gertrude Lindsay w 5 Years 38 Years Perm Librarian Central H

H enry Jennings w 5 Years 19 Years Perm

Chemistry, Physics,

General Math Central H

David Pitts w 4 Years 9 Years Perm Football Coach Central H

Irene Fulmer w 4 Years 20 Years Perm Biology Central H

Era Dickey w 4 Years 18 Years Perm English I V Central II

Charles Spears w 4 Years 6 Years

3 Y r

P rob

Phys. Ed. (B oys)

B iology Central H

Martha M cDaniel w 4 Years 38 Years Perm Am erican H istory Central H

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education £

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

M ary Farrar w 4 Years 28 Years Perm Typing, Shorthand Central H

Delane H olland w 2 Years 4 Years

3 Yr

P rob English I Central H

R oy Sweeney w 5 Years 34 Years Perm

Algebra I I ,

Plane Geometry Central H

Gilbert Smith w 4 Years 6 Years

2 Y r

P rob

Geography I,

Band Director Central H

F loyd Graham w 6 Years 19 Years

1 Y r

Prob

Am erican H istory

Problem s o f Dem ocracy Central H M ay 3, 1965

Joan W hite w 4 Years 4 Years

1 Y r

P rob English I I I Central H M ay 3, 1965

Jim m y Stewart w 4 Years 0 Years P rob

Problem s o f Dem ocracy

English I I Central H Ju ly 16, 1965

M aurice Ellis w 4 Years 1 Year Prob

Typing, Gen. Business,

Geography I Central H July 16, 1965

Jim m y Buchanan w 3 Years 0 Years P rob

D rafting,

Manual Arts Central H Ju ly 6, 1965

Elna Spears w 4 Years 4 Years

3 Yr

P rob English I I , Science I Central H

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education $

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

K aty Todd W 4 Years 3 Years

1 Y r

Prob

Geography I,

Girls Phys. Ed. Central II Ju ly 16, 1965

Charlotte Graham W 4 Years 18 Years Perm H om e Economics Central H

Thelma Parks W 4 Years 5 Years Perm

Science I

H om e Economics Central H

Ralph Hastings W 5 Years 18 Years Perm

Guidance Counselor

Vocational Agriculture Central H

Jane H yder W 4 Years 1 Year

1 Y r

P rob

English I I

Spanish I & I I Central H

Gordon W ood W 4 Years 1 Year Prob

Solid Geom., Trig.

A lgebra I Central H Aug. 20, 1965

Martha Crawford w 4 Years 8 Years

1 Y r

Prob

Solid Geom., Trig.

A lgebra I Central H Dec. 6, 1965

Eldred Tueker w 5 Years 21 Years Perm Supervising Principal 8th Dist. E

Bessie Daves w 3 Years 32 Years Lim. 1st Grade 8th Dist. E

Kathleen Griffin w 4 Years 37 Years Perm 5th Grade 8 th Dist. E

Minnie W alker w 5 Years 33 Years Perm 2nd Grade 8th Dist. E

M orelle M cNatt w 4 Years 27 Years Perm 8th Grade 8th Dist. E

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

E m esting W ilson W 4 Years 17 Years Perm 7th Grade 8th Dist. E

Vilm a McGee W 4 Years 32 Years Perm 3rd Grade 8th Dist. E

Elizabeth Buntin W 4 Years 21 Years Perm 4th Grade 8 th Dist. E

Ruth M organ W 4 Years 25 Years Perm 7th Grade 8th Dist. E

Virgin ia Davidson w 4 Years 23 Years Perm 1st Grade 8th Dist. E

M ildred Quinn w 4 Years 12 Years Perm 1st Grade 8th Dist. E

Alberto Buntley w 5 Years 19 Years Perm 6th Grade 8th Dist. E

D illon Smith w 3 Years 25 Years Lim. 8th Grade 8th Dist. E

Mink V iley w 4 Years 21 Years Perm 3rd Grade 8th Dist. E

Thelma Farrar w 3 Years 9 Years Lim. 5th & 6th Grades Comb. 8th Dist. E

Evelyn W hitaker w 3 Years 26 Years Lim. 4th Grade 8th Dist. E

Lynn Norman w 3 Years 30 Years Lim. 2nd Grade 8th Dist. E

M ary Conger w 4 Years 15 Years

3 Y r

P rob 2nd & 3rd Grades Comb. 8 th Dist. E

A nn Leftwich w 4 Years 1 Year

1 Y r

Prob 5th Grade 8th Dist. E

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education fy

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Allan Haynes W 4 Years 0 Years Prob

Social Science 6

Math., & 6-8 P .E . 8th Dist. E August 2, 1965

M argaret Curtis N 5 Years 9 Years Perm Special Education 8th Dist. E

Russell M cAlister W 2 Years 35 Years Lim. Principal, 8th Grade F lora E

Lucille Robertson W 3 Years 30 Years Lim. 4th Grade F lora E

M ary Ramsey w 3 Years 22 Years Lim. 2nd Grade F lora E

Johnnie W alker w 4 Years 35 Years Perm 3rd Grade F lora E

Robbie W alker w 2 Years 4 Years Lim. 1st Grade F lora E

Joy K ing w 2 Years 1 Year

1 Y r

P rob 5th Grade Flora E

R ay LaFevers w 2 Years 1 Year

1 Y r

P rob 6th Grade F lora E

W orley M cK inney w 3 Years 0 Years Prob 7th Grade F lora E July 16, 1965

W arner Simmons w 2 Years 20 Years Lim. P rincipa l; 7th Grade Flintville E

Kattie Snoddy w 2 Years 20 Years Lim. 2nd Grade Flintville E

Elwyin W alker w 3 Years 17 Years Lim. 8th Grade Flintville E

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education $■

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Lois W insett W 4 Years 33 Years Perm 3rd Grade Elintville E

Esther Rudder W 3 Years 28 Years Lim. 1st Grade Elintville E

Loretta M addox w 4 Years 5 Years Perm 5th Grade Flintville E

Ida P igg w 3 Years 28 Years Lim. 4th Grade Flintville E

A rlin Sims w 2 Years 14 Years Lim. 7th Grade Flintville E

R uby Clark w 4 Years 27 Years Perm 7th Grade Flintville E

Shields Templeton w 4 Years 2 Years

2 Y r

P rob 6th Grade Flintville E

Joe Yann w 4 Years 16 Years Perm Principal Flintville H

F. C. Duggin w 4 Years 18 Years Perm Phys. Ed. Flintville H

K ittie Porter w 5 Years 27 Years Perm

Chemistry, Spanish,

Physics, Guidance Flintville H

M argaret Jennings w 4 Years 22 Years Perm English, Librarian Flintville H

Sue Colden w 5 Years 25 Years Perm H om e Econom ics Flintville H

B illy W arren w 4 Years 1 Year

1 Y r

P rob

Am erican H istory

W orld H istory Flintville H

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education fy

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Late of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Paul Currin w 4 Years 3 Years

3 Y r

P rob B iology Flintville H

M ary S. Taylor w 4 Years 19 Years

3 Y r

Prob

English, Gen. Scienee,

Guidance Flintville H

D wight Storey w 4 Years 4 Years

3 Y r

Prob

Gen. Science, Gen. Bus.,

Typing Flintville H

W innie R. Currey w 5 Years 30 Years Perm English I I I & IV Flintville H

M ary E. Barnes w 4 Years 0 Years Prob

Shorthand, Typing,

Bookkeeping Flintville H A p ril 5, 1965

Jeannette Mullins w 4 Years 4 Years Perm English I & I I Flintville H

Con S. Massey w 4 Years 22 Years Perm Vocational Agriculture Flintville H

John Taylor w 4 Years 0 Years P rob

A lgebra I & I I

Mathematics I I I & IV Flintville H Aug. 30, 1965

James Stephens w 4 Years 8 Years Perm Supervising Principal Highland Rim

Iva Henderson w 2 Years 29 Years Lim. 4th Grade Highland Rim

Pranees Burton w 2 Years 9 Years Lim. 5th Grade Highland Rim

Eula D. Sawyers w 3 Years 35 Years 6th Grade Highland Rim

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education Sr

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Jable Dean W 4 Tears 7 Years

2 Y r.

P rob 7-8 Mathematics Highland Rim

Christine Abbey W 3 Years 2 Years

2 Y r

P rob 1st Grade Highland Rim

Joan W atson W 3 Years 8 Years

1 Y r

P rob 3rd Grade Highland Rim

M ildred Cooper W 6 Years 14 Years

2 Y r

P rob Science 7, Librarian Highland Rim

Glenda Chamblee w 4 Years 1 Year

1 Y r

P rob 4th Grade Highland Rim

Gail Crane w 3 Years 2 Years

2 Y r

P rob 1st Grade Highland Rim

Virgin ia Jean w 4 Years 6 Years

1 Y r

P rob English 7, 8 H ighland Rim

Lou Templeton w 3 Years 2 Years

1 Y r

P rob 5th Grade Highland Rim

A nn Bolles w 4 Years 0 Years P rob 2nd Grade H ighland Rim A p r. 5, 1965

Elsie Mills w 3 Years 34 Years Lim. 2nd Grade Highland Rim

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Statxis Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date o f Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Newton Gray W 2 Years 0 Years Prob

Phys. Ed.

Social Studies 8 H ighland Rim A pr. 20, 1965

M ary Lemons N 4 Years 25 Years Perm 6th Grade Highland Rim

Alm a Graham W 4 Years 7 Years Prob 3rd Grade Highland Rim Sept. 7, 1965

Darlena H ardin N 4 Years 9 Years Perm

7 & 8 Social Studies

Science 8 Highland Rim

Audra Grisham W 3 Years 24 Years

Principal

Grades 5-8 H owell E

Oleta Campbell w 4 Years 17 Years Perm Grades 1-4 H owell E

W . C. Richardson w 4 Years 6 Years

2 Y r

P rob

Principal

Grades 7-8 K elso E

Ruth W in ford w 2 Years 25 Years Lim. Grades 3-4 K elso E

Lucy Crawford w 4 Years 33 Years Perm Grades 5-6 K elso E

Emma Brandon w 1 Year 29 Years Grades 1 & 2 K elso E

Jane W essman w 4 Years 8 Years Prob Grade 1 Lincoln E Aug. 20, 1965

C. L. Joan Jr. w 5 Years 8 Years Perm

Principal

Grade 8 Lincoln E

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Bace

Education

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Louise F lynt W 4 Years 28 Years Perm Grade 2 Lincoln E

Martha Mansfield W 2 Years 17 Years Grade 7 Lincoln E

W aweda Coble W 5 Years 20 Years Perm Grade 6 Lincoln E

Carrah Jared w 3 Years 13 Years Perm Grade 1 Lincoln E

Juanita Jean w 4 Years 16 Years Perm Grade 3 Lincoln E

Beryl H arbin w 4 Years 3 Years Perm Grade 5 Lincoln E

Jerry H oney w 4 Years 0 Years P rob Grade 4 Lincoln E A ug. 2, 1965

Era Mae C raw ford w 8 Years 29 Years

Principal

Grades 7 & 8 M ulberry E

Ellen Graham w 4 Years 18 Years Perm Grades 4, 5, & 6 M ulberry E

Trances Small w 3 Years 17 Years Lim. Grades 1, 2, & 3 M ulberry E

Thurman Cobb w 5 Years 20 Years Perm Principal

Grade 8 Petersburg E

Sara Talley w 4 Years 33 Years Perm Grade 4 Petersburg E

Marie Beech w 3 Years 4 Years Lim. Grade 3 Petersburg E

M ildred Scott w 4 Years 28 Years Perm Grade 5 Petersburg E

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education $

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

T enure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Bate of Employ-

ment (new

teachers)

Helen Bowers w 4 Years 12 Years Perm Grade 7 Petersburg E

M ary Taylor w 4 Years 23 Years Perm Grade 1 Petersburg E

Loutella Battebo N 5 Years 18 Years Perm

Grade 2

Special Education Petersburg E

George H oward N 4 Years 10 Years Perm Grade 6 Petersburg E

P eggy Eddins W 4 Years 0 Years Prob Grade 2 Petersburg E Nov. 1, 1965

Clyde M oore w 4 Years 32 Years Perm

Principal

Grade 8 T aft E

M arian T aftt w 4 Years 33 Years Perm Grades 6 & 7 T a ft E

Mildred Gray w 4 Years 31 Years Perm Grades 4 & 6 T a ft E

Frances Barron w 5 Years 10 Years Perm Grade 1 T a ft E

Omali W allace w 3 Years 36 Years Lim. Grades 2 & 3 T aft E

Hazel Askins N 4 Years 4 Years Lim. Grades 2 & 5 T a ft E

James Bain w 4 Years 3 Years Perm

Principal

Grades 6, 7, & 8 Vann E

Patsy Sisk w 4 Years 5 Years Perm Grades 1 & 2 Vann E

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education 4

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Martha Gunter W 4 Years 7 Years

1 Y r

P rob Grades 3, 4, & 5 Vann E July 16, 1965

A jelbert Dumas N 5 Years 27 Years Perm

Principal, Chemistry

Unified Geometry W est End H

Jesse W inlock N 4 Years 17 Years Perm

Social Studies,

Band Director W est End H

Thomas M cDonald N 4 Years 13 Years Perm

Gen. Science, B iology,

Health & P.E . W est End H

W illiam Battle N 4 Years 20 Years Perm

Arithm etic, Health

Football Coach W est End H

Joe Askins N 4 Years 7 Years Perm

Typing, General Business,

Shorthand W est End H

Channie P igg N 4 Years 24 Years Dim. Grades 1, 2, 3 W est End E

Lura S. G regory N 3 Years 29 Years Lim. Grades 4, 5, 6 W est End E

Beulah Dumas N 4 Years 37 Years Perm English, Librarian W est End H

Ann Bady N 5 Years 16 Years Perm

English

Y oc. H om e Ec. W est End H

L. C. Curtis N 4 Years 16 Years Perm Y oc. T & I W est End H

A

pp

en

di

x

B

Name of Teacher Race

Education Sr

Qualifica

tions

Length of

Employ

ment

Tenure

Status Nature of Subjects Taught

Assigned

School

Date of Employ

ment (new

teachers)

Charles Eady N 4 Years 12 Years Perm

Economies, Science,

H istory W est End H

Betty Sherwood W 4 Years 3 Years

3 Y r

Prob Special Education, (illegible) Countywide

Sue Burroughs W 5 Years 20 Years Perm Special Education, (illegible) 8th District

Graeie D rom on w 3 Years 9 Years Prob Special Education, (illegible) 8th District

W ilson Sullivan w 2 Years 3 Years

3 Y r

Prob Special Education, (illegible) Countywide

Oeda Craig w 4 Years 15 Years Perm Special Education, S & E Countywide

Lois W hite w 5 Years 33 Years Perm

Spanish Instructor