Defendants Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law Following Hearings on Metropolitan Detroit Desegregation Plans

Public Court Documents

May 5, 1972

18 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Defendants Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law Following Hearings on Metropolitan Detroit Desegregation Plans, 1972. 965e69f4-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6931a219-b808-4cbc-abfb-12f4becd1e60/defendants-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law-following-hearings-on-metropolitan-detroit-desegregation-plans. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

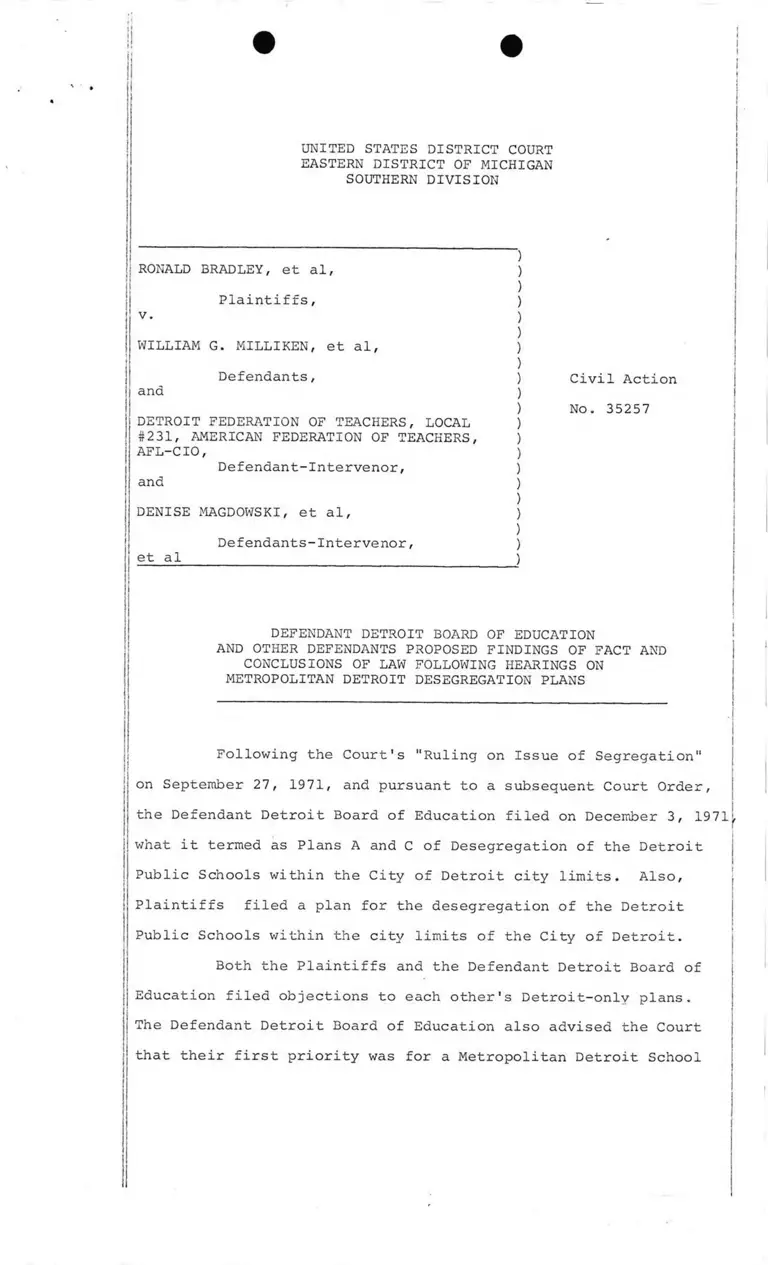

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

)RONALD BRADLEY, et al, )

)Plaintiffs, )

v. )

)WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al, )

)Defendants, )

and )

)DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL )

#231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, )

AFL-CIO, )

Defendant-Intervenor, )

and )

)DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al, )

)Defendants-Intervenor, )

et al________________________________ )

Civil Action

No. 35257

DEFENDANT DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION

AND OTHER DEFENDANTS PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT AND

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW FOLLOWING HEARINGS ON

METROPOLITAN DETROIT DESEGREGATION PLANS

Following the Court's "Ruling on Issue of Segregation"

on September 27, 1971, and pursuant to a subsequent Court Order,

the Defendant Detroit Board of Education filed on December 3, 1971

j what it termed as Plans A and C of Desegregation of the Detroit

j Public Schools within the City of Detroit city limits. Also,

! Plaintiffs filed a plan for the desegregation of the Detroit

Public Schools within the city limits of the City of Detroit.

Both the Plaintiffs and the Defendant Detroit Board of

Education filed objections to each other's Detroit-only plans.

The Defendant Detroit Board of Education also advised the Court

that their first priority was for a Metropolitan Detroit School

Desegregation Plan. The Court issued a "Ruling on Propriety of

Considering a Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish Desegregation of

the Public Schools of the City of Detroit," dated March 24, 1972,

wherein the Court concluded: .

"We conclude that it is proper for a Court

to consider a metropolitan plan directed

toward the desegregation of the Detroit

Public Schools as an alternative of the present

intra-city desegregation plan before it and,

in the event that the Court finds such intra

city plan inadequate to segregate such schools,

the Court is of the opinion that it is required

to consider a metropolitan remedy for desegre

gation . "

The Court also,on March 24, 1972, reaffirmed, beginning

March 28, 1972, that there would be hearings on a metropolitan

Detroit desegregation plan. Hearings were held on March 28, 29,

30, April 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12 and 13, 1972, at which time

Defendant State Board of Education, Defendant Detroit Board of

Education, Defendant-Intervenors, Denise Magdowski, et al, and

Plaintiffs Ronald Bradley, et al, presented metropolitan Detroit

desegregation plans for the consideration of the Court during

the said hearings.

During the course of said hearings, on March 28, 1972,

the Court issued "Findings of Facts and Conclusions of Law on

Detroit-only Plan of Desegregation" holding as a factual matter

that:

"In summary, we find that none of the three

plans Would result in desegregation of the

public schools of the Detroit School District."

The Court also concluded as a matter of law:

"...that the Court must look beyond the limits

of the Detroit School District for a solution

to the problems of segregation, in the Detroit

Public Schools is obvious; that it has the

authority, nay, more, the duty to (under the

circumstances of this case) do so appears

plainly anticipated by Brown II, 17 years ago.

While other school cases have not had to deal

with our exact situation, the logic of their

application of the command of Brown II supports

our view of our duty."

- 2-

The Defendant Detroit Board of Education presents the

following findings of fact and conclusions of law as to a viable

and educationally-sound metropolitan Detroit desegregation plan.

1. The metropolitan community of Detroit, properly

defined, consists of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb County. The

Defendant Detroit Board has presented substantial evidence to this

effect, and although plans have been presented which would dese

gregate a smaller area, no one has disputed that the metropolitan

area is other than as stated above (Marz, City Tr.205-8).

2. Within this area, there is a high degree of inter

governmental cooperation. The area is connected by a common sewe

and water system, a metropolitan park system,, a metropolitan trans

portation authority and,county-by-county,intermediate school

districts which cooperate on a substantial number of educational

programs, particularly with regard to special education (Marz,

City Tr.208-13; Rankin, Metro Tr.441; 444).

3. Within this area, substantial commutation occurs,

not only from out-county Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties into

Detroit, but from Detroit to these suburban districts, and also

between the various suburban districts (Marz, City Tr.205-8).

4. Numerous citizens prominent in the affairs of the

City of Detroit currently reside in these suburbs, including a

former chairman; of the Detroit Board of Education (Flynn, Metro

Tr.933; 944-5).

5. School children within and without the City of

Detroit perceive the schools located within the suburbs as being

within the same metropolitan community as their own schools

(Foster, City Tr.361-3).

6. There is a natural metropolitan school community

defined objectively by social interchange, or subjectively by the

perception of school children which is congruent-with the

-3

metropolitan area (Marz, City Tr.205-13; Foster, City Tr.361-3),

7. The exclusion of all-white or all-black schools or

school districts within that community from the jurisdiction of

this Court would have the effect of preserving racially idertifiable

schools within the community. The pernicious and

constitutionally prohibited effect of the existence of such

schools is not diminished by the fact that such a school is not

located within the school district of the City of Detroit, or

any other particular school district (Rankin, Metro Tr.1328).

8. The Detroit Metropolitan School Community is both

geographically extensive, and, due to the density of population,

subject to traffic congestion. Both of these circumstances miti

gate against a plan of desegregation which would involve children

from every school district in the community in pupil

exchanges with Detroit schools (Smith, Metro Tr.1105-11;

Morshead, Metro Tr.26-7; Foster, Metro Tr.1205; Def.Ex.M-12).

9. A plan which would require busing between all parts !

of the metropolitan school community and the City of Detroit

would impose unreasonable burdens of travel, both in terms of

time and distance, both on the children coming to Detroit from

the suburbs, and on the children going from Detroit to the suburbs

(Foster, Metro Tr.1205; Rankin, Metro Tr.412).

10. The Defendant Detroit Board of Education has proposed

a plan which creates a series of clusters. Each cluster consists

of several suburban school districts, together with one or more

of the high school attendance zones or constellations within the

City of Detroit (Def.Ex.M-11).

11. These clusters are designed primarily so that each

cluster reasonably reflects, although not with absolute mathe-

:

matical precision, the racial proportion of the entire metropolitan

school community (Rankin, Metro Tr.430-3).

- 4-

12. The plan submitted by the Defendant Detroit Board

of Education encompasses all of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb County,

but two of the clusters, one in Northern and Western Oakland

(Cluster 12) and another in Northern and Northeastern Macomb

(Cluster 18) counties include no territory within the school

district of the City of Detroit (Rankin, Metro Tr.418; 440).

13. In each such cluster, the included suburban school

districts are contiguous. The Detroit high school constella

tions included within each cluster are contiguous with one

another, but are not generally contiguous with the suburban

districts in the same cluster (Def.Ex.M-12).

14. The clusters are designed in such a fashion that

generally those suburban areas more distant from the central

city are paired with Detroit high school attendance zones at or

near the outer limits of the City. Those suburban districts

close to or adjacent to the Detroit city limits are paired with

Detroit high school attendance zones closer to or at the center

of the City. The effect of this design is to minimize and equali

the maximum travel and distance times within the various clusters

and to insure that no school child would be required to travel

from the outer perimeter of those clusters exchanging students

with the City of Detroit (Rankin, Metro Tr.423-6; Def.Ex.M-12)

to the very center of the City.

15. In determining which school districts should be

included in particular clusters, the Defendant Detroit Board

of Education, in addition to its primary concern for the racial

balance of the clusters, considered the socio-economic status

("SES") of the students in the school districts involved (Rankin,

Metro Tr.412; 430-3; 460;402;409).

16. There is substantial record evidence to support the

contention of the Defendant Detroit Board of Education and its

- 5-

!!:

expert witnesses Guthrie and Rankin, that the probability of a

poor child profiting from formal education is strongly influenced

by the presence or absence of significant numbers of children of

middle or high socio-economic status in his learning situation.

There is, in addition, substantial record evidence that a middle

class child does not suffer from being placed in a situation in

which children of low SES are present provided the low SES

j

children do not preponderate (Rankin, Metro Tr.409 ; 591-2; 610-614|;

Guthrie, City Tr.452-4; 455-7; 518-21). I!17. The Defendant Detroit Board of Education utilized |

in drawing their plan the average SES of the various metropolitan

districts and Detroit high school constellations as determined by

the state-wide test of SES included in the Michigan Educational

Assessment Program for 1971 (Rankin, Metro Tr.433).

18. The utilization of SES in order to determine which

particular school districts should be placed in a particular

j cluster is a reasonable educational judgment which the Court

should and does credit. The establishment of SES balance contri

butes to and insures the educational soundness of the plan.

19. In addition to the establishment of non-contiguous

clusters (a technique commonly referred to as a "skipping"

technique), the clusters proposed by the Defendant Detroit Board

of Education are designed to follow as much as possible major

transportation arteries leading into and out of the City (Rankin,

Metro Tr.424-5).

20. The record evidence indicates that the vast majority‘ i

of all of the suburban districts included within those clusters

of the Detroit plan which include Detroit high school constella

tions are accessible to downtown Detroit (the foot of Woodward

Avenue at the Detroit river) within forty minutes; all of them

- 6 -

■

■

’

1

are within fifty minutes and much of their territory is accessible:

within thirty minutes. As the clusters are designed to follow

transportation arteries which radiate from the center of the City,

and as noted in findings above,the clusters require no one to move

from the outer perimeter all the way downtown, it is reasonably

probable that a transportation plan could be designed for these

clusters which provides for a maximum direct bus travel time,with

very few exceptions, of under forty minutes (Smith,Metro Tr.1101-

4; Foster,Metro Tr.1168-74; Pl.Ex.M-8).

21. The transportation survey provided,pursuant to the

Order of this Court,by the Defendant State Board of Education,

indicates that a number of school districts currently operate bus

routes in excess of an hour in duration (one way). The Utica Schoc

District operates a number of runs of 70 to 90 minutes duration,

1

and the Huron Valley School District operates runs of up to one

hour and forty-five minutes one way. Runs of forty-five to fifty-

five minutes are commonplace. There is no record evidence which

indicates that bus runs of this duration are detrimental to educag

tion (Survey and Evaluation of Existing School Transportation By

— ■ - ■ ■ " --------------------------- i

Defendants State Board of Education (undated,received by counsel

May 1,1972,pages unnumbered), Huron Valley School Distirct bus noS.

21,35,51; Utica Community Schools bus nos.1,3,7,8; see inter alia

Center Line, Roseville, Chippewa Valley,Warren Woods,Birmingham,

Avondale, Troy,Farmington,Rochester, Walled Lake,Garden City,

Inkster,Livonia and Fairlane ) .

22. It is a reasonable and,indeed,virtually certain expec

tation that a plan of transportation can be designed which could

limit travel times and distances within the cluster plan of the

Defendant Detroit Board of Education well below a point at which

time and energy expended by children in travel would interfere with

their ability to participate in the educational process (Rankin,

Metro Tr.402;412-416;423-9; Henrickson,Metro Tr.700-1;703-4;716-8;

Def.Ex.M-16-18).

- 7-

23. Several other perimeters for the exchange of pupils

were suggested to the Court. Plan 3,of the six submitted but not

advocated by the Defendant State Board of Education, suggested an

"Initial Operating Zone" which includes those school districts

immediately adjacent to the City of Detroit,and a few school dis

tricts one district removed from the City (State Bd.Def.Ex.M-5;

Pierce,Metro Tr.247-9).

24. The racial proportion of the school population withir

the IOZ would be between 35% and 40% black,or between 10% and 15%

higher than that of the total metropolitan area (Pierce,Metro Tr.

242-50).

25. Establishment of the IOZ would require drawing an arti

ficial line through the heart of the metropolitan community,separa

ting school districts which,in terms of their metropolitan character,

are otherwise indistinguishable into those in which blacks did

attend school and those in which only whites attend school (Def.

Ex.M-5).

26. Such a plan would also provide instant and pervasive

resegregation,as many established middle class communities are

located immediately outside of the IOZ (Pierce,Metro Tr292-7).

27. Although the plan speaks of the later addition of

territory to the operating zone if need be,the Court finds that

the mere existence of this possibility is insufficient to prevent

serious resegregation (Pierce,Metro Tr.252;292-7).

28. Plans were also presented by the Plaintiffs,and by

Defendants-Intervenor Denise Magdowski,et al. Defendants-Inter-

venor's plan divided some,but not all of the metropolitan area into

seven "boroughs" in which pupil assignment patterns would be devel

oped. Although the boroughs then serve the same function as the

clusters proposed by the Defendant Detroit Board of Education,they

differ in that they are totally contiguous,eschewing the "skipping"

technique developed by the Defendant Detroit Board. Like the Deferj-

. Idant Detroit Board's clusters,two boroughs contain no territory

from the City of Detroit,with one each located in Northern Oakland

and Northern Macomb County (Morshead,Metso Tr.28;30-1;Def.Ex.M-2),

- 8-

29. The Plaintiffs have presented a plan which proposes

mixing of pupils within a perimeter congruent with that proposed

by Defendants-Intervenor, except for the addition of the Bloom

field Hills and West Bloomfield School Districts, and the sub

traction of boroughs VI and VII, the two boroughs proposed by

Defendants-Intervenor which include no territory of the City

of Detroit (PI.Ex. M-ll & 12; Foster, Metro Tr.1159-50).

30. The clusters prepared by the Defendant Detroit Board

of Education which involve interchange with the City of Detroit

include the following school districts which are excluded from

the perimeter proposed by Plaintiffs and from boroughs I-V of

Defendants-Intervenor1s plan (Def. Ex M-ll):

Chippewa Valley

Utica

Avondale

Walled Lake

Novi

Northville

Plymouth

Van Buren

Huron

Woodhaven

Gilbraltar

Flat Rock

Trenton

Grosse lie

31. Of these districts, all but four show SES scores

above the State mean (Def. Ex. M-ll).

32. The vast majority of these districts are clearly

metropolitan in character; that is, school children they serve

are in large part the off-spring of families who work, shop and

recreate throughout the metropolitan area and who perceive them

selves and are perceived by others as integral parts of the

metropolitan area (Def.Ex.M-12; Flynn,Metro Tr.943-4;951-60).

33. The high SES scores of these school districts

reflect the relatively high degree of affluence found in the

neighborhoods which make up these districts. As indicated above,

this affluence is not the product of economic enterprise separate

from the metropolitan area, but is a reflection of the fact

that these districts include areas in which more affluent resi

dents of the metropolitan community have chosen to settle. To

exclude these districts from the metropolitan plan would not only

result in an artificial division within the metropolitan community

9-

leaving an all white fragment outside the metropolitan desegre

gation plan, but would mean that that fragment would represent

a portion of the wealth of the metropolitan community dispor-

portionate to the numbers of its population (Flynn,-Metro Tr.929

33; 1024-6; Def.Ex.M-11).

34. It has often been noted, in this trial and elsewhere;,

that the more affluent whites are the most likely to leave a

situation which involves the presence of black children in the

schools which their children attend. The presence abutting the

perimeter of the desegregation plan proposed by Plaintiffs of a

number of disproportionately high SES suburban communities,in

which high SES whites could easily establish residence without

losing any of the benefits of living in the metropolitan area,

would have uhe natural,probable and foreseeable consequence of

causing the resegregation of the school districts of the metro

politan community, making those districts outside the perimeter

more white, and those within the perimeter more black (Guthrie,

City Tr.462-5; Rankin, Metro Tr.402;414).

35. The racial proportion of the clusters proposed by the

Defendant Detroit Board of Education, including the districts

discussed above, is slightly closer to the racial proportion

of the tri-county area than those proposed by Plaintiffs (Foster,

Metro Tr.1164-5; Rankin, Metro Tr.431;1183; 1214-17;1234-5).

36. Adoption of the perimeter proposed by the Defendant

Detroit Board of Education is necessary to desegregation of the

schools of the City of Detroit. Adoption of a smaller perimeter

would leave extant racially identifiable schools within the

metropolitan community and within the perceptions of black students

from Detroit, on a non-random basis sanctioned by the order of

this Court and not occasioned by reasons of public convenience

and necessity. It would further provide an open invitation to

resegregation; and would, by depriving the area being desegregated

- 10-

O.L a large number of high SES students lessen the probabilities

that the plan could be operated in a fashion which would provide

equal opportunity for a quality education (Flynn, Metro Tr.929-

30; 939-59).

| i

37. No party has disputed the contention that those school

districts which are included in clusters 12 and 18 proposed by the

Defendant Detroit Board of education may reasonably be excluded

from pupil assignments mixing students from those school districts^

with students from the City of Detroit. The parties are in accord

that the travel distances involved are too great, and v/ould, for

| a substantial number of the students in those districts and for

students from Detroit who might be transported to such district

represent an impairment of their ability to participate in the

j educational process (Rankin, Metro Tr.439-40; Flynn, Metro Tr.

930; 471-2; Morshead, Metro Tr.26-9).

38. Nonetheless, clusters 12 and 18 contain school

districts which are equally metropolitan in character, whichI

provide obvious possibilities for the relocation of upper-middle

class whites leading to resegregation, and which, with the

exception of Mt. Clemens and Pontiac, are clearly racially

identifiable as white. The maintenance of these districts with

out inclusion in the plan would leave schools segregated by

j operation of law within the metropolitan school community, which

■ "

would, in turn, mean that schools racially identifiable as all

white would persist within the metropolitan school community.

Inclusions of clusters 12 and 18 are,therefore, necessary to

the maintenance of desegregation in Detroit,now and hereafter

(Flynn, Metro Tr.939-59; Foster, Metro Tr.1212-13).

39. No plan presented to the Court provides a detailed

plan for pupil assignment within the metropolitan area. The

amount of detail varies, the plan of the Defendant Detroit Board

- 11-

of Education being most specific in terms of methods of pupil

assignment and criteria for cluster development. All plans

submitted, including the Plaintiffs' plans are in the form of

guidelines or outlines, requiring a very substantial amount of

additional planning before implementation in detail would be

possible. (Foster, Metro Tr.1292; Rankin, Metro Tr.463-6; Pierce,

Metro Tr.251;547-9; Def.Ex.M-2;M-3;M-4;M-5;M-6;M-7;M-8;M-9;M-10;

Pl.Ex.M-12). This is no reflection on the diligence of those

who have presented plans since the presentation of the Defendant

State Board of Education; the time available was simply not ample

for the enormity of the task (Foster, Metro Tr.1210-12;1292-6).

40. A number of the plans speak of "governance systems"

which would not only be responsible for the further elaboration

of the plan proposed, but to varying degrees, for the continuing

government of the newly-desegregated schools of the metropolitan

community (Pierce, Metro Tr.248-9; Def.Ex.M-5). The Defendant

State Board of Education plan 3 speaks of a School Desegregation

Commission of the State Board of Education; Defendants—Intervenor

speaks of an Office of Metropolitan School Desegregation

(Dei•Ex.M-2; Morshead, Metro Tr.31) and the Defendant Detroit

Board of Education plan speaks of a Metropolitan Desegregation

Authority (Rankin,Metro Tr.437-8;659; Def.Ex.M-10). The

Defendant State Board of Education plan would reserve to the

state officials' the right to appoint members of the Commission;

the Defendants-Intervenor would have the authority of the office

flow from the "Borough Boards" which would, in turn, draw their

authority from the local Boards, and the Defendant Detroit Board I

of Education plan would provide for a seven-person authority,

drawing two members from the State Board of Education, two from

the Detroit Board of Education, and one each from the three

Intermediate School. Boards which are, themselves, elected by local

12-

Boards which comprise the metropolitan school community.

41. This authority would have general power over the

total desegregation process, but would only involve itself

directly in the drawing of pupil assignment plans in the event

of an impasse between the various districts within the cluster

(Rankin,Metro Tr.438-43; 661; Def.Ex.M—10). It is undisputed

that the State of Michigan has, by statute, delegated the vast

majority of the duties involved in the day-to-day running of its

educational system to the local Boards of Education (M.S.A.§15„ j

3563-3622). The knowledge, therefore, of the vast majority of

the details necessary to draw a workable pupil assignment plan

resides with the local school districts. It is, therefore, appro

priate and necessary to the effective implementation of the plan

that representatives of local school districts, including the

Detroit School District, be directly represented in the drawing

of pupil assignment patterns and also in any central controlling

authority (Henrickson, Metro Tr.681-2; Rankin,Metro Tr.428).

42. By providing for the development of pupil assignment

plans within the various clusters, rather than on a general basis,

the Defendant Detroit Board of Education has sought to reduce the

job of developing such plans to manageable proportions, thereby

reducing the period of time which would be required to accomplish

the task. Nonetheless, development of initial pupil assignment

plans can reasonably be expected to take eight weeks, with sub

stantially more time required to develop an effective transpor

tation system and resolve local problems necessary for implemen

ting the assignment plan (Henrickson,Metro Tr.779,797; Kuthy,

City Tr.188-9).

43. The "Governance system," or method for further

implementation proposed by the Defendant Detroit Board of Education

is, therefore, one which realistically promises to work and to

work in the shortest possible amount of time (Def.Ex.M-10; Rankin,

Mei.ro Tr.428;442-5;483-5;493-4;579-80; 1330;139-3; Henrickson,

Metro Tr.681-2;Foster, Metro Tr.1298;1317).

- 13-

44. There is credible record testimony that the maximum j

possible desegregation which might be accomplished by the Fall j

of 1972 would be the desegregation of three school grades. There

is additional expert testimony to the effect that both,for reasons

of the ability of that particular age group to adapt to change j

and because that particular age group does not make a very large

I

number of extraordinary demands on the physical plant of the

schools they attend, that the optimal grades to start with would

be either the fourth, fifth and sixth or fifth, sixth and seventh

grades (Rankin,Metro Tr.463-8;512-4;669-671; Morshead, Metro Tr.

32-4;152;196-8).

45. No witness conversant with the details of school

operation in the Detroit metropolitan area was willing to state

!

with certainty that three such grades, or approximately 225,000

students could definitely be moved into an operational plan of

desegregation by September of 1972. There was, however, credible

testimony that such an achievement represented a reasonable

target, or goal (Rankin,Metro Tr.463-8;512-4;669;671;1333-6;

Morshead, Metro Tr. 89-90;191-2; Pierce, Metro Tr.351-7; Foster,

Metro Tr.1177-78; 1236-8; 1261; 1396-7; 1314; 1317;1384-6).

46. It was not seriously disputed by any of the parties

that the mere reassignment of pupils on a basis reasonably reflec

ting the racial proportion of the metropolitan school community

in and of itself, was insufficient to insure the desegregation

of the Detroit schools, and the provision of equal educational opportunity

throughout the metropolitan school community. The plan of the

Defendant Detroit Board of Education particularly spoke at length

to such matters as the need for in-service training for teachers

who may never have had to teach students of another race, for

the presence of black faculty members and administrators in

previously all-white suburban schools so that the particular needs

and concerns of black students could be vocalized at decision-

- 14-

making levels; for plans which would make possible inclusion

in parental activities and expression of concern for the schools

their children attend by parents who might live at some distance

from the schools for insurance against the growth of segregation

within a particular school through the use of such practices

as tracking; for the development and implementation of curricula

which would reflect the broadened racial and socio-economic

spectrum which would be present within the several schools of

the community, and the utilization of educational materials which

are not uniracial in nature (Rankin,Metro Tr.403-409; 469-71;

1342-50; 1382-3; Def.Ex.M-10).

47. The Court finds that all of the above concerns are

reasonably related to the ability of the State of Michigan to

maintain the schools of the Detroit metropolitan area in a unit

ary fashion hereafter, and to continue to provide equality of

educational opportunity throughout the metropolitan school

community. Failure to provide safeguards with regard to these

matters would be detrimental to the probability that the plan

would promise to work in the future.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. Having found de jure segregation, it is the duty of

this Court to order the implementation of a plan of school dese

gregation which provides the "maximum possible school desegre

gation" and which "reasonably promises to work" now and hereafter.

Bradley v. Milliken, ___ F.Supp___,Findings of Fact and Conclusior

of Law on Detroit-Only Plans,slip op.p.4; Green v. County School

Board, 391 U.S.430; Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S.19; Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board,396 U.S.

290; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,402 U.S.l.

s

- 15-

#

2. Having previously found that desegregation of the

schools within the confines of the City of Detroit is not possible;

fulfilling this obligation requires that this Court exercise its

jurisdiction over the entire metropolitan school community. To

do otherwise would be to draw artificial, constitutionally impermi

ssible boundaries through the community, leaving a number of the

schools of the community in a segregated circumstance. Bradley v.

Richmond,---F.Supp.___ (slip op.p.64-65); Haney v. County Board

of Education of Sevier County,410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir.1969); Hall

Xr_St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F.Supp 649 E.D.La.1961

g-ff'd- 287 F.2d 376 (5th Cir.1961); and 368 U.S.515 (1962); Lee

v. Macon County Bd. of Educ.,448 F.2d 746,752 (5th Cir.1971);

Gomillion v. Lightfoot,364 U.S.339 (1960); Turner v. Littleton—

Lake Gaston School Dist.,442 F.2d 584 (4th Cir.1971); United

States v. Texas,447 F.2d 551 (5th Cir.1971).

3. The Court may, and has, properly considered factors

of public convenience and necessity, educational soundness, and

the possibility of resegregation, in determining which plan to

adopt. The Court should, and has, credited the educational

judgments of those who will be responsible for providing educa

tional opportunities under the plan. In the absence of any

educational judgments made by the Defendant State Board of

Education us to a particular plan, the Court credits the judgments

of the Defendant Detroit Board of Education. Allen v. Asheville

_ _Bd. of Educ., 434 F.2d 902 (4th Cir. 1970); Bradley v. School

Bd. O-L Ricnmond, 325 F . Supp . 828,832 — 33 (E .D .Va . 19 71) ; Green v.

School Bd. of City of Roanoke, 316 F.Supp.6 (W.D.Va.1970),aff'd.

in part,vacated in part on other grounds,444 F.2d 99 (4th Cir.1971);

Moore v. Tangipahga Parish School Bd.,304 F.Supp.244 (C.D .La.1969),

appeal dism.421 F.2d 1407 (5th Cir.1969).

-16-

4. As the plan proposed by the Defendant Detroit Board

of Education does provide the maximum possible desegregation and

realistically promises to work, does not interfere with the

public convenience and necessity and provides for educational

soundness, it is appropriate for adoption by the Court. Davis v.

School Dist. of City of Pontiac, 443 F.2d 573,577 (6th Cir.1971),

j cert.denied,404 U.S. 913 (1971). See also Swann v. Charlotte-

j Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,306 F .Supp.1291,1297 (W.D.N.C.1969).

5. It is also appropriate for this Court to issue orders

‘ designed to protect the desegregation achieved by adoption of

the plan, by preventing tracking and other techniques of internal

segregation, and by requiring that careful attention be paid to

such matters as the presence of blacks in faculty and admini

strative positions, involvement of parents of all races in the

schools, in-service training of teachers and the like. Johnson

v. Jackson Parish School Board, 423 F .2d 1055 (5th Cir.1970);

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd.,444 F .2d 1400 (5th Cir.1971);

Monroe v. Bd. of Commissioners of City of Jackson,Tenn., 427 F.

2d 1005, 1008 (6th Cir.1970); Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Sep.

School District, 419 F.2d 1211,1219 (5th Cir.1970), cert.denied,

396 U.S. 1032 (1970); United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of

Educ.,380 F.2d 385,394, affirming en bare,372 F.2d 836 (1966),

cert.denied sub'nom, Caddo Parish School Bd, v. United States,

389 U.S.840 (1967); Stell v. Board of Educ. for the City of

Savannah and the County of Chatam,387 F.2d 486 (5th Cir.1967).

Respectfully submitted.

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Date: May 5,_____ ,1972. Telephone: 962-8255

Attorneys for Defendant Detroit

Board of Education

- 17-

C E R T I F I C A T I O N

Thl£7 X% ^ certify that a copy of the foregoing Defendant:

Detroit Board of Education and Other Defendants Proposed Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law Following Hearings on Metropolitan

Detroit Desegregation Plans has been served upon counsel of

record by United States Mail, postage pre-paid, addressed asfnl 1 owe: •

iI

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

•DOUGLAS H. WEST

ROBERT B. WEBSTER

3700 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

NATHANIEL R. JONES

General Counsel, NAACP

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. WINTHER MC CROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

I

| JACK GREENBERG

i NORMAN J. CHACIIKIN

| 10 Columbus Circle

j New York, New York 10019

♦WILLIAM M. SAXTON

1881 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

♦EUGENE KRASICKY

Assistant Attorney General

Seven Story Office Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

• THEODORE SACHS

1000 Farmer

Detroit, Michigan 48226

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL R. DIMOND

ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center for Law & Education

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

02138

•ROBERT J. LORD

8388 Dixie Highway

Fair Haven, Michigan 48023

Of Counsel:

PAUL R. VELLA !

EUGENE R. 30LAN0WSKI

30009 Schoenherr Road

Warren, Michigan 48093

PROFESSOR DAVID HOOD

Wayne State University Law

468 West Ferry

Detroit, Michigan 48202

• ALEXANDER B. RITCHIE

2555 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

BRUCE A. MILLER

LUCILLE WATTS

2460 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

* RICHARD P. CONDIT

Long Lake Building

860 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

48013

♦KENNETH B. MC CONNELL

74 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

48013

School

Date: 7*19 72.

Respectfully submitted,

G'&U't T.

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Telephone: 962-8255May fj