Attorney Notes on Allen Park Petition for Rehearing En Banc

Working File

January 1, 1972

6 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Attorney Notes on Allen Park Petition for Rehearing En Banc, 1972. b711d381-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/69661a65-d110-4b21-adc1-5226251a9375/attorney-notes-on-allen-park-petition-for-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

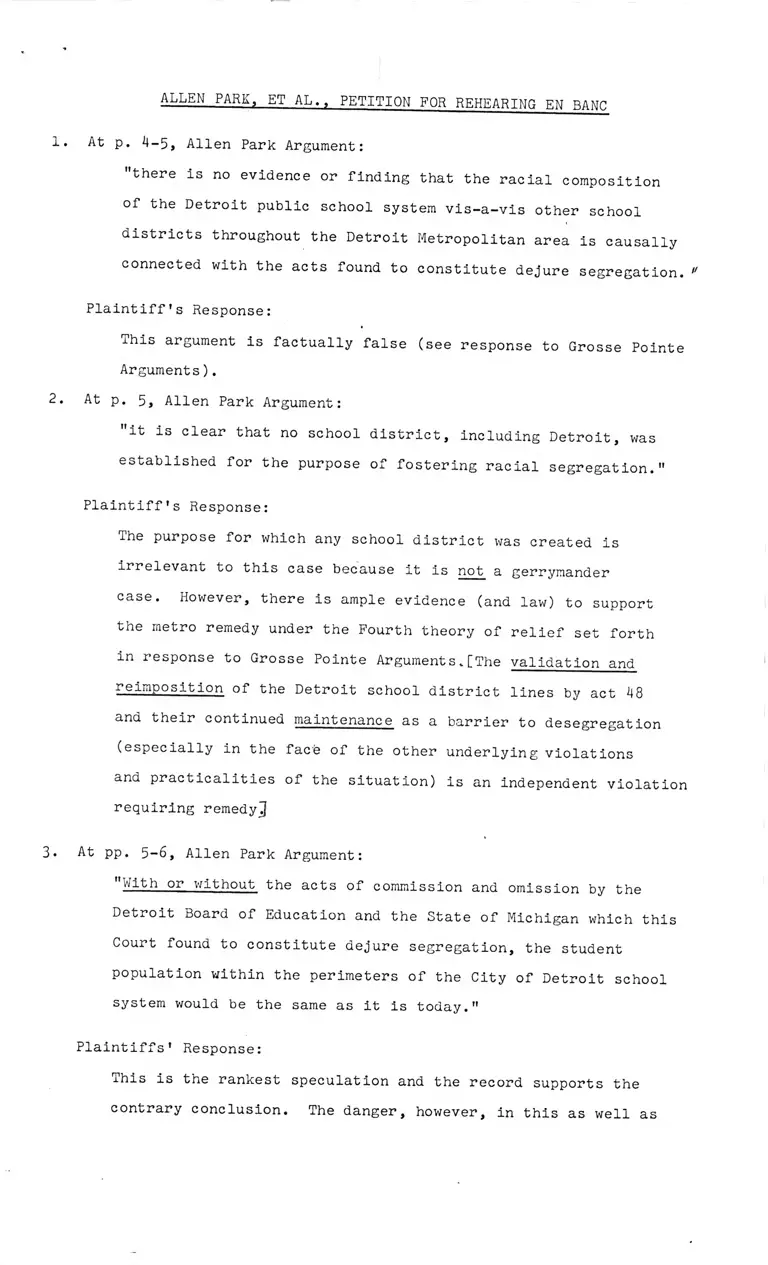

ALLEN PARK, ET AL., PETITION FOR REHEARING EN BANC

At p. 4-5, Allen Park Argument:

"there is no evidence or finding that the racial composition

of the Detroit public school system vis-a-vis other school

districts throughout the Detroit Metropolitan area is causally

connected with the acts found to constitute dejure segregation.

Plaintiff's Response:

xhis argument is factually false (see response to Grosse Pointe

Arguments).

At p. 5, Allen Park Argument:

"it is clear that no school district, including Detroit, was

established for the purpose of fostering racial segregation."

Plaintiff's Response:

The purpose for which any school district was created is

irrelevant to this case because it is not a gerrymander

case. However, there is ample evidence (and law) to support

the metro remedy under the Fourth theory of relief set forth

in response to Grosse Pointe Arguments„[The validation and

reimposition of the Detroit school district lines by act 48

and their continued maintenance as a barrier to desegregation

(especially in the face of the other underlying violations

and practicalities of the situation) is an independent violation

requiring remedy^

At pp. 5-6, Allen Park Argument:

"With or without the acts of commission and omission by the

Detroit Board of Education and the State of Michigan which this

Court found to constitute dejure segregation, the student

population within the perimeters of the City of Detroit school

system would be the same as it is today."

Plaintiffs' Response:

xhis is the rankest speculation and the record supports the

contrary conclusion. The danger, however, in this as well as

the next argument is that suburban intervenors should have the

opportunity to prove the factual argument that the school

racial composition is wholly "due to residential patterns."

4. At p. 6, Allen Park Argument:

"This Court, in disregard of the facts, has in reality declared

that a big city school system which is predominantly black due

to residential patterns, surrounded by suburban school districts

which are predominantly white, due to residential patterns,

constitutes a denial of equal protection of the law."

Plaintiff's Response:

This statement is true only insofar as it disregards the

facts. The District Court held that the Detroit school system

became predominantly black in part due to state "school"

action and refusal to act of pervasive extentj'1/state ''school"

action and inaction without the City and along school

district lines contributed to making Detroit a predominantly

black school system and the suburbs a predominantly white

set of schools; and that any plan limited to the City of

Detroit, given these practicalities of the situation, would

merely identify all schools in Detroit, and the Detroit

School System, as "black" by official action, i.e., another

dejure act, a court ordered resegregation plan.

5. At p. 7, Allen Park Argument:

Proof that state action caused the racial imbalance between scU

is a requisite for relief.

Plaintiffs' Response:

A. For all the reasons stated in response to other arguments,

we have shown that causal connection.

B. If illegal state action includes the conjunction of state-

imposed residential segregation built upon by pupil

assignment practices which cause school segregation, then

. this causal connection is fully supported by the record.

(McCree likes this notion).

C. The "causal connection," however, need only be by "validation

2

or augmentation" of the residential segregation. (In any

event, however, the illegal acts are attributed only to

state defendants and Detroit defendants).

At pp. 7-8, Allen Park Argument:

There is no proof that school construction outside Detroit

contributed to school segregation, unless it is constitutionally

impermissible for a school district to construct schools

within its own geographical limits to accomodate the residents

therein ̂ (citing Deal).

Plaintiffs' Responses:

A. The factual premise is false because the record fully

supports the finding that school construction outside

Detroit contributed to school segregation. (See Response

B to Grosse Pointe Argument "1". Once again, however,

our danger is that even if we argue that such proof goes

only to the state defendants' violation, suburban districts

“Pas.V \ ~ V a . u ,

\should have an opportunity to rebut or show otherwise

they are bound by it. One issue for us to consider,

then, is whether we are confident that we can win on theories

that don't include state violations in the suburbs. See

Argument 7 below).

At pp. 9-10, Allen Park Argument:

"This Court, like the District Court, has concluded that

(i) the Detroit school system is operated as a dejure segregated

system; (ii) the State of Michigan through acts of commission

and omission has countenanced or abetted the situation found

extant in Detroit; (iii) all school districts are instrumentalities

of the State; (iv) therefore the District Court may use all

school districts in the Detroit Metropolitan area to effect a

change in the racial complexion of the Detroit school system."'

This violates principles of Deal and Swann about the scope

of the remedy fitting nature of the violation.

Plaintiffs' Responses:

A. There are other theories of violation and remedy (discussed

elsewhere).

B. The "results of" segregatiorTjin a place with as many children

as Detroit necessarily affects surrounding schools sufficiently

to include those parts of suburbia necessary to provide

Detroit school children "just schools, now and hereafter."

(For example, contrary to Allen Park's argument on p. 10,

the effect of the dejure segregation operation of the Detroit

school system is that but for the acts complained of,

children in Detroit would be attending schools (1) having

a racial composition more nearly in accord with the

racial makeup not of the Detroit School district, but

rather of the Detroit metro area, and (2) not having their

racial identity affixed (or validated) by state action .

C. The nature of violation wholly within the City of Detroit

does authorize the scope of metro remedy unless school

district lines are a barrier to equitable relief where

school attendance zones are not; for "state action" is

"state action" is "state action." The only limits to

relief are (1) the jurisdiction of the Court over the

parties and (2) any compelling state interests which can

only be promoted if the disestablishment of "Black"

schools is limited to the City of Detroit. (No one has

shown that the existing patterns of school segregation or

school governance are necessary to the promotion of any

compelling state interest. Indeed, the only asserted

justification for existing arrangements, on this record,

p r £ < : r - i f ' t

is their/existance.)

D. Where state level, as opposed to local level, action is

implicated in the violation, the scope of the remedy may

include all aspects of the state system of public education

necessary to accomplish relief.

7. At p. 10, Allen Park Argument:

"There is no evidence that black children have been denied

access to any suburban district school on any ground other

than lack of residence within the school district, a requirement

- i| _

equally applicable to white children.”

Plaintiffs’ Responses:

A. Allen Park’s "access” notion is no longer the law of violation

nor is it the law of remedy. (e.g., maximum actual

desegregation possible taking into account the practicalities

of the situation).

B. Even under theories of "effective exclusion," Allen Park's

factual premise falls: there is ample evidence in the record

/the requirement of residence" [and the actual assignment

of children to schools] operates [in lockstep1! to contain

black children to separate and distinct areas and schools

within Detroit and exclude black children from outlying

areas within Detroit and most suburban areas and schools.

And all this in the face of school district lines which

bear no relationship to other boundaries, are crossed for

many educational services, and have been crossed in the

past, to promote segregation. And all of the above has

been so found by the District Court. ( Su. />/>• 52- 51).

9. At pp. 11-13, Allen Park Argument:

The only basis for the panel's and District Court's metro

desegregation is that if Detroit operated on "open—access"

notion, each school would be 65$ black, "with the prospect

that future population changes would increase the Black to White

ratio; such basis "erroneously assumes that desegregation

means effecting a racial balance which is predominantly white

irrespective of the residential patterns of the school district

to be desegregated" in violation of Swann's prohibition of

racial balance.

Plaintiffs' Responses:

A. A reading of Metro findings shows that District Court

obviously not interested in achieving any particular racial

balance, but rather maximum actual desegregation and a

system of just schools taking into account the practicalities

of the situation.

■ B. Allen Park assumes the validity of the argument they seek

to prove is valid, i.e., that desegregation is limited by

_ - 5 - •

school district lines.

C. Citation of racial statistics in Emporia and Scotland-Neck

is a non-sequiter; for those districts were all surrounded

by counties predominantly black', ̂ equity courts are limited

in desegregation by time and distance (e.g., the South

Dakota example contrasting with the Southern Black belt,

but the law the same) and shouldn’t go any further than

have to (i.e., limit area of pupil reassignment by con

struction controls). .

D. The Fourteenth Amendment speaks to the state system of

public education wherein all vestiges of the state

containment of some 175,000 black children in state-imposed

blacx: schools, and the assignment of hundreds of thousands

of white children to white schools, is eliminated root

and branch. We believe that the District Court's Ruling

and Findings on Metro hold promise of outlining a system

which will substitute just schools now and hereafter.

If, in flushing out that outline, that promise proves

false, or if the state defendants or suburban intervenors

come in with a more effective alternative, then the

District Court stands open to, and from his past record, will

make appropriate modifications.

6