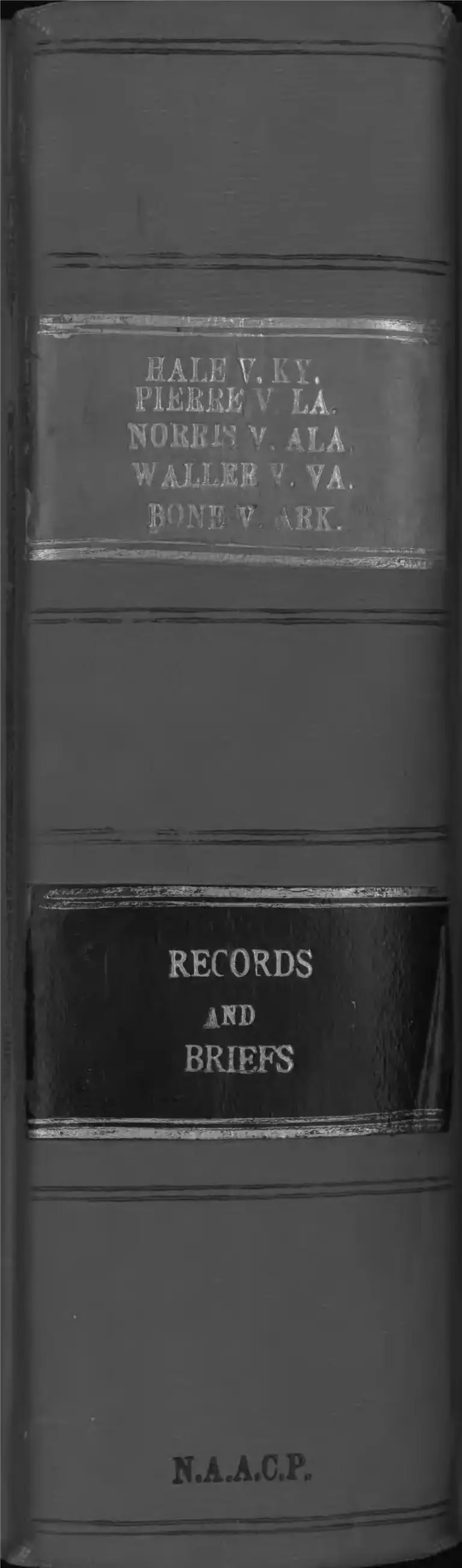

Hale v. Kentucky and Other Criminal Justice Cases Records and Briefs

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1934 - January 1, 1941

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hale v. Kentucky and Other Criminal Justice Cases Records and Briefs, 1934. eb364047-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/69f1c992-48f8-40c1-8350-8710cd21af21/hale-v-kentucky-and-other-criminal-justice-cases-records-and-briefs. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Copied!

HALE \T, EX

M J S B R K >' LA.

m i m n v . a l a

VALISE VA

B-WJ?V vl?X

i "irirai T r r a a a i

R E C O R D S

/

*

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD

Supreme Court o f the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1937

No. 680

JOE HALE, PETITIONER,

vs.

COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY

ON WHIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS OF THE COM

MONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI FILED JANUARY 8, 1938.

CERTIORARI GRANTED JANUARY 31, 1938.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1937

No. 680

JOE HALE, PETITIONER,

vs.

COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS OF THE COM

M ONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY

INDEX.

Proceedings in Court of Appeals of Kentucky............................

Caption .....................................................(omitted in printing)..

Record from Circuit Court of McCracken County.....................

Indictment ....................................................................................

Order setting case for trial.......................................................

Order to deliver defendant for trial......................................

Order overruling motion to set aside indictment...............

Order overruling demurrer to indictment............................

Order granting defendant, Joe Hale, a separate trial___

Plea of not guilty ........................................................................

Empanelling of jury....................................................................

Order overruling motion to discharge panel.......................

Minute entries of trial................................................................

Affidavit supporting motion to set aside indictment.........

Supplemental affidavit and stipulation..................................

Motion to discharge panel.........................................................

Order allowing witness fees.....................................................

Order on instructions..................................................................

Verdict ...........................................................................................

Instruction “A”, refund..............................................................

Instructions to jury ....................................................................

Original Print

1 1

1

2 1

2 1

5 3

5 3

6 3

6 4

0 4

7 4

7 4

8 5

8 5

9 6

21 14

22 15

23 16

23 16

24 17

25 17

25 17

Judd & Detweiler (I nc.) , Printers, Washington, D. C„ February 4, 193&

—3814

11 INDEX

Record from Circuit Court of McCracken County— Continued.

Motion for new trial...................................................................

Judgment .......................................... ............................................

Order overruling motion for new trial and granting ap

peal ............................................................................................

Motion to proceed in forma pauperis and order thereon.

Order approving bill of exceptions........................................

Clerk’s certificate........................... (omitted in printing)..

Bill of exception No. 1 ...............................................................

Testimony of Dr. Leon Higdon........................................

Ed Kirk .......................................................

J. E. Linn.....................................................

Terrell Toon ..............................................

Buddy Mercer ..........................................

Leo Poat .....................................................

Eugenia Hamilton....................................

Lindsey Mae Hamilton...........................

Mrs. Mamma J. Eggester.......................

Prince William Thorpe.........................

Edward Lee Boyd....................................

Terrell Toon (recalled).........................

James Powell ..........................................

Novella Nailing ........................................

Bertie Mae Bradfort................................

Reporter’s certificate...........(omitted in printing)..

Judgment ...............................................................................................

Opinion, Morris, C................................................................................

Order extending time to file rehearing..........................................

Petition for rehearing........................................................................

Order denying rehearing....................................................................

Petition for appeal and order staying execution (omitted

in printing) .......................................................................................

Assignment of errors..............................(omitted in printing)..

Affidavit and motion to proceed in forma pauperis (omitted

in printing) .......................................................................................

Order allowing appeal........................... (omitted in printing). .

Citation and service................................(omitted in printing)..

Pneeipe for record..................................(omitted in printing). .

Clerk’s certificate ..................................(omitted in printing)..

Order dismissing appeal and staying mandate to permit ap

plication for a writ of certiorari (omitted in printing)-----

Stipulation and addition to record.................................................

Motion to set aside indictment.................................................

Affidavit of clerk..........................................................................

Order allowing certiorari ..................................................................

Original Print

28 20

30 21

30 22

30 22

32 23

32

33 23

33 23

36 26

38 27

41 30

45 33

47 34

50 36

59 43

66 48

68 50

75 56

76 57

77 58

79 60

81 62

82

83 63

84 63

99 71

100 72

104 74

105

107

110

117

120

121

122

123

127 74

128 75

130 76

131 77

1

sTb

[fol. 1] [Caption omitted]

[fol. 2]

IN CIRCUIT COURT OF McCRACKEN COUNTY

Commonwealth oe K entucky, Plaintiff,

vs.

Joe Hale, Prince W illiam T horpe, and James Gilbert

Martin, Alias Junkiiead, Defendants

Pleas Begun, Had and Ended under the Hon. Joe L. Price,

Judge McCracken Circuit Court, and the Hon. Joe L.

Price at All Times Presiding

Be it remembered that on the 4th day of the September

Term, and on the 1st day of October, 1936, the following or

der was entered herein, v iz :

This day the Grand Jury, in the presence of the entire

body, by and through its foreman, in open court, returned 14

indictments, which were received by the Clerk from the

Judge, each was endorsed A True Bill, and signed E. H.

Seaton, Foreman; bail was endorsed thereon, and each was

ordered filed, bench warrants awarded and ordered to issue

on each indictment as follows:

One against Joe Hall, Prince William Thorpe, and James

Gilbert Martin, alias Junkhead, charged with the offense of

“ Wilful Murder” , no bail endorsed. No. 3432.

The indictment, filed pursuant to the above court order,

is in words and figures as follows, to w it:

[fol. 3] Indictment

T he Commonwealth op K entucky

against

Joe H ale, Prince W illiam T horpe, and James Gilbert

Martin, alias Junkhead

M cCracken :

The Grand Jurors of the County of McCracken in the

name and by the authority of the Commonwealth of Ken

tucky accuse Joe Hale, Prince William Thorpe, and James

Gilbert Martin, alias Junkhead, of the offense of wilful mur

der, committed in manner and form as follows, to-wit: The

1—680

2

said Joe Hale, Prince William Thorpe, and James Gilbert

Martin, alias Junkhead, in the said county of McCracken on

the'1st, day of "October, 1936 and with — years before 'find

ing tins indictment, dicTwillfuliy and unlawfully and ma-

IiciousIV~and feloniouslv~ancl of tneir malice aforethought,

hill, slay and murder W. Jtc. Toon by cutting, thrusting, stab

bing, and wounding said W. R. Toon in and upon the head,

body, arms, limbs and person with a knife, a sharp-edged

and pointed instrument, a deadly weapon, from which cut

ting, thrusting, stabbing and wounding, said W. R. Toon

did shortly thereafter, and within a year and day and in the

Commonwealth of Kentucky die, contrary to the form of the

Statute in such cases made and provided, and against the

peace and dignity of the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

Second Count

The Grand Jurors of the County of McCracken, in the

name and by the authority of the Commonwealth of Ken

tucky accuse Joe Hale, Prince William Thorpe, and James

Gilbert Martin, alias Junkhead, of the offense of wilful mur

der, committed in manner and form as follows, to-wit: The

[fol. 4] said Joe Hale, in the said county of McCracken, and

on the 1st day of October, 1936, and before the finding of this

indictment, did willfully and unlawfully and maliciously and

feloniously, and of his malice aforethought, kill, slay, and

murder W. R. Toon by cutting, thrusting, stabbing, and

wounding said W. R. Toon in and upon the head, body,

arms, limbs and person of said W. R. Toon with a knife, a

sharp-edged and pointed instrument, a deadly weapon, from

which cutting, thrusting, stabbing and wounding said W. R.

Toon did shortly thereafter, and within a year and a day,

and in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, d id : ------

and the said Prince William Thorpe and James Gilbert Mar

tin, alias Junkhead, were present at the time and near

enough so to do, and did wilfully and feloniously and unlaw

fully, and maliciously, and of their malice aforethought, aid,

assist abet, counsel, encourage, and command, thn-said Joe

“Gale tcTso cut, thrust, stab, and wound and kill and murder

fhe smxTwTK Toon at the time he, the said Joe Hale, did so

so ; contrary to the form of the Statute in such cases made

and provided, and against the peace and dignity of Com

monwealth of Kentucky.

HOLLAND G. BRYAN,

Corn. Atty., Second Judicial Dist.

3

[fol. 5] I n Circuit Court of McCracken County

[Title omitted]

Order Setting Case for Trial— October 2, 1936

On Motion of Commonwealth Attorney, it is ordered that

this prosecution be placed upon the docket; and by agree

ment of parties, said prosecution is set for trial on October

12, 1936.

I n Circuit Court of McCracken County

[Title omitted]

Order to Deliver Defendant for Trial— October 10, 1936

The above styled prosecution having heretofore on Octo

ber 2, 1936, been set for trial on October 12th, 1936, as to

the defendant, Joe Hale, he being now for safe keeping in

the State Penitentiary at Eddyville, Kentucky, it is now

ordered that the Warden of said Penitentiary deliver said

defendant, Joe Hale, into the custody of Cliff Shemwell,

Sheriff of McCracken County, or his deputy or deputies, for

the purpose of transporting said defendant, Joe Hale, to

the above mentioned Court for trial on said date of October

12, 1936.

[fol. 6] I n Circuit Court of McCracken County

[Title omitted]

Order Overruling Motion to Set A side I ndictment__Octo

ber 12, 1936

Came defendant, Joe Hale, by attorney, and filed motion

and moved the Court to set aside the indictment in the above

staled prosecution, and in support of said motion to set

aside, filed his own affidavit and his supplemental affidavit,

and paities hereto also filed stipulation, which stipulation

is set out at the foot of said supplemental affidavit and said

motion to set aside being submitted to the Court, and the

court being sufficiently advised, overrules said motion to set

aside, to which ruling of the Court the defendant excepts.

4

Order Overruling D emurrer jtjiJusumctment—October 12,

1936

Came defendant, Joe Hale, by attorney, and entered de

murrer to the indictment herein, which demurrer being sub

mitted to the Court, and the Court being sufficiently advised

overruled said demurrer, to which ruling of the Court the

defendant excepts.

Order Granting Separate Trial— October 12, 1936

Came defendant by attorney, and entered motion and

moved the Court for a separate trial, and said motion being

submitted to the Court, and the Court being advised, sus

tained said motion, it is therefore ordered that the defend

ant, Joe Hale, have a separate trial. Whereupon the Com

monwealth by attorney, elected to try the defendant, Joe

Hale, first.

[fol. 7] Pee a of Not Guilty—October 12, 1936

Came parties to the above styled prosecution and an

nounced ready for trial.

On motion of Commonwealth Attorney, it is ordered that

Marshall Jones, this Court’s Official Reporter, report the

trial of this Prosecution. The defendant, Joe Hale, being-

present in open court, in person and by attorneyt acknowl

edged the identity of person, waived the formality of ar

raignment, and entered a plea of not guilty to the charge of

“ wilful murder.”

E mpanelling of Jury— October 12, 1936

The regular panel of jurors being tested for the jury in

this prosecution, and four (4) having been accepted and

Five (5) others having been called but not yet accepted,

and it appearing to the satisfaction of the Court, that the

regular panel has been eshausted, deputy sheriffs, Herman

Englert, Clyde Shemwell, Barkley Graham, J. R. Waller

and Helen Bohannon, having been duly sworn, took charge

of the above mentioned Nine (9) jurors until One o ’clock

P. M. and by agreement of parties, said deputies were

ordered and directed to go out into the City and County,

5

and into the parts thereof where men would not be likely to

be disqualified as jurors in this prosecution, and summon

50 men as jurors to complete the jury in this prosecution.

One o ’clock P. M. having arrived, the sheriff turned into

court the names of Kelly Warford, Court Neal, Fayettee

Trewalla, John C. Kipley, Jesse Carneal and M. V. Miller,

from among the above mentioned 50 summoned by the

sheriff, who together with Jim Polk, Jim Travis, Fred Babb,

Amos Rickman, A. J. Harris, and John Wyatt, from the

regular panel, were duly tested, accepted and sworn as the

jury herein. Then at the direction of the Court to turn in

a name from among the above mentioned 50 as the 13th

[fol. 8] juror, the sheriff turned into Court the name of

R. L. Bailey, who was duly tested, accepted and sworn as

the 13th juror in this prosecution, and who took his place

with the other 12 regular jurors as above mentioned.

Order Overruling Motion to Discharge Panel— October

12, 1936

Then came defendant, by attorney, and filed motion and

moved the Court to discharge the whole panel of the jury

in this prosecution for cause, he having exercised his 15

peremptory challenges as allowed T)y law, and in support

of said motion referred to and made a part hereof the affi

davit of the defendant, this day filed in support of hi a mn-

tion to set aside the indictment herein. And said motion to

discharge coming on to be heard, and the court being suffi

ciently advised, overruled said motion to discharge, to

which ruling of the Court the defendant excepts.

Minute E ntries of Trial— October 12, 1936

At the conclusion of a part of Commonwealth’s evidence,

the defendant, Prince William Thorpe, being unwilling to

testify, it is thereupon ordered, on motion of Common

wealth by its Attorney, that the indictment herein as to said

defendant, Prince Willaim Thorpe, be dismissed absolutely,

reasons endorsed thereon. Thereupon said Prince William

Thorpe was called to the witness chair by Commonwealth

Attorney, and said witness refused to give his testimony,

whereupon said Prince William Thorpe was ordered to the

jail of McCracken County in custody of the jailer. The jury

6

was then admonished by the Court and permitted to depart,

in custody of Deputy Sheriffs, Herman Englert, J. R.

Waller and Barkley Graham, they having first been duly

sworn, until tomorrow morning at 8 :00 o ’clock.

[fol.9] I n Cibctxit Court of M cCracken County

[Title omitted]

A ffidavit Supporting Motion to Set A side I ndictment—•

Filed October 12, 1936

The defendant and affiant, Joe Hale, in support of his

motion to set aside the indictment against him herein,

states that the population of McCracken County, Kentucky,

is approximately 48,000 of which approximately 8,000 are

colored people, ox negroes; he states that the qualification

of jurors prescribed by the Kentucky Statutes, section

2241, are as follows:

“ The commissioners shall take the last returned Asses

sor’s book for the county and from it shall carefully select

from the intelligent, sober, discreet, and impartial citizens,

O § resident housekeepers in different portions of the county,

over twenty-one years of age the following numbers of

names of such persons, to-wit: * * * Counties having a

population of twenty thousand and not exceeding fifty

thousand, not less than five hundred nor more than six

5 C®? | hundred. ’ ’

Affiant now states that there now appears on the last

returned Assessor’s Book for the County the names of

approximately 6,000 white persons and 700 negroes quali

fied for such jury service under the above requisite.

He states that he can prove this fact by C. C. Cates, the

Assessor or Tax Commissioner for McCracken County at

■ the present time.

r~ He states that in December, 1935, by order of the Judge

of the McCracken Circuit Court, Boyce Berryman, J. JI.

Hodges, and W. C. Seaton, were duly and regularly ap-

[fol. 10] pointed Jury Commissioners and filled the wheel

jjb >5 I with_names for jury service for the year 1936, to the extent

of between 500 and 600; that he can prove by the three

g above named commissioners that they did not place the

h _ 4 ro

3 V

name of one negro in the wheel but that the whole number

selected were of white citizens; that they did not exclude

the name of any negro from said wheel because he was not

an intelligent, sober, discreet and impartial citizen, resi

dent housekeeper of this county or twenty-one years of age.

He "states "that it is further prescribed by the Kentucky

’ Statutes, Section 2243, that the “ Judge, in open Court,

shall draw from said drum or wheel case a sufficient number

of names to procure the names of twenty-four persons qual

ified as hereinafter prelffinbedyfo act as Grand Jurors * * *

“ The qualification as such Grand Jurors, Section 2248 of

Ky. Statutes, namely: “ No person shall be qualified to

serve as a Grand Juryman unless he be a citizen and a

housekeeper of the county in which he may be called to

serve and over the age of twenty-one years. No civil offi

cer, (except trustees of schools) no surveyor of a highway,

tavern-keeper, vender of ardent spirits by license, or per

son who is under indictment, or who has been convicted of

a felony and not pardoned, shall be competent to serve as

a grand juror * * *

He now says that he can prove by the Hon. Joe L. Price,

Judge of the McCracken Circuit Court, that the names of

the grand jurors for the present term of court, at which

this indictment was returned, was drawn by him from the

drum or wheel as above prescribed; that he did not draw

the name of one negro citizen from said wheel, and that

he did not exclude any negro’s name from the said list of

[fol. 11] grand jurors so drawn because “ he was not” “ a

i citizen and a housekeeper of the county in which he was

called to serve; because he was not twenty-one years of age;

because he was a civil officer (except trustee of school)

because he was a surveyor of a highway; because he was

a tavern-keeper; because he was a vendor of ardent spirits

by license; because he was under indictment; nor because

Jie had been convicted of a felony and not pardoned.

# # # # # # #

/ —

The affiant now states, that he can prove by John W.

Ogilvie that he was sheriff of McCracken County, Ken

tucky, during the years 1906 to 1910; that he attended every

term of the criminal court for said McCracken Circuit

Court during that time; that he and his deputies sum

moned the jurors for the grand jury and petit jury service

8

°o

*O T

i

during that tenure, and that not one negro was summoned

to serve or served on any Grand Jury or petit jury during

said time; nor were the name of any negro placed in his

hands to be summoned for such service.

He says that he can prove by Geo. Houser that he was

the sheriff of McCracken County, Kentucky, from 1910 to

1914; that he attended every term of the criminal,court for

the said McCracken Circuit Court during that time; that

he and his deputirs summoned the jurors for the grand

jury and petit jury service during that tenure, and that

not one negro was summoned to serve or served on any

grand jury or petit jury during said time; nor were the

name of any negro placed in his hands to be summoned for

such service.

[fol. 12] He says that he can prove by George Allen that

1 he was sheriff of McCracken County, Kentucky, during the

years from 1914 to 1918; that he attended every term of the

criminal court for the said McCracken Circuit Court during

that time; that he and his deputies summoned the jurors

for the grand and petit jury service during that tenure,

and that not one negro was summoned to serve or served

on any grand jury or petit jury during said time; nor were

the names of one negro placed in his hands to be sunl

it moned for such service.

r He says that he can prove by George L. Alliston that

he was sheriff of McCracken County during the years 1918

to 1922; that as such he attended every term of the crim

inal court held in said county for the McCracken Circuit

Court during that time; that he and his deputies summoned

the jurors for the grand jury and petit jury service during

that tenure, and that not one negro was summoned to serve

or served on any grand jury or petit jury during said time;

nor were the name of any negro placed in his hands to be

summoned for such service.

p Tie says he can prove by Roy Stewart that he was sheriff

of McCracken County, Kentucky during the years ^922 to

1926; that as such he attended every term of the criminal

court held in said county for the McCracken Circuit Court

during that time; that he and his deputies summoned the

jurors for the grand jury and petit jury service during that

tenure, and that not one negro was summoned to serve or

served on any grand jury or petit jury during said time ;

nor was the name of any negro placed in his hands to be

summoned for such service.

9

He says he can prove by Claud Graham that he was

sheriff of McCracken County during the years 1926 to 1930;

that as such he attended every# term of the criminal court

[fol. 13] in said county for the McCracken Circuit Court

during said time; that he and his deputies summoned the

jurors for the grand jury and petit jury service during

that tenure, and that not one negro was summoned to serve

or served on any grand jury or petit jury during said time.;

nor was the name of any negro placed in his hands to be

summoned for such service,

I He saysTthat lie can prove by Herman Englert that he

was deputy-sheriff under EmmeiH.olLXxhicaaa&d) who was

sheriff of McCracken County during the years 1930 to 1934;

that as such he attended every term of the criminal court

held in and for the McCracken Circuit Court during that

time; that he and other deputies summoned the jurors for

the grand jury and petit jury service during said time, and

that not one negro was summoned to serve or served on

any grand jury or petit jury during said time; nor was the

name of any negro placed in his hands to be summoned for

such service.

He says that he can prove by Cliff Shemwell that he has

been since 1931 and is now the present sheriff of McCracken

County, Kentucky; that as such he has attended several

terms of the criminal court in and for the McCracken Cir

cuit Courc; that he and his deputies summoned the jurors

for the grand jury and petit jury service for the past two

years and that not one negro was summoned to serve or

1 served on any grand fury or petit jury during said time:

nor was the name of any negro placed in his hands to be

summoned for such service.

— He says that he can prove by all of the above named

ex-sheriffs that they never saw a negro sit on either a grand

jury or petit jury in the McCracken Circuit Court for the

I past thirty years.

I r a n i ] He says he can also prove by Geo. L. Alliston

that he was deputy U. S. Marshal stationed at Paducah,

McCracken County, Ky. for eight years consecutively im

mediately preceding the year 1935: that he is a citizen and

resident of Paducah, Kentucky and has been for twenty

years or more, that he is well acquainted with the negro

l ln| population of Paducah and McCracken County, Kentucky

rj and will state that there is now and has been for the pas£.

— twenty years negro' citizens in said county that meet all

the requirements of the law relating to jurors and are qual-

] ified for jury service to the extent of five hundred or more;

that during that time several negro citizens from this

county have been summoned, met the qualifications, and

y served as jurors in the U. S. Court in Paducah, Ky.

He says he can prove by Walter Blackburn that he was

clerk of the U. S. Court at Paducah, Ky. for twelve years

immediately preceding the year 1936; that he is wellZ ac

quainted with the negro citizenship of McCracken County

and has been during said time; that he will state that there

are five hundred or more negro citizens in this county that

meet every qualification under the law for jury service; that

during his tenure of office several negro citizens have served

on the juries in the U. S. Court at Paducah; that he has

never seen a negro serve on a petit or grand jury in the

UMcCracken Circuit Court. "

T He says Tie can prove by Wayne C. Seaton that he was

clerk of the McCracken Circuit Court for twelve years im

mediately preceding the year, 1928; that he attended every

term of the McCracken Circuit Court during his tenure of

office, that he never saw a negro set on either grand jury

or petit jury during his tenure of office; he will also state

that he is a resident and citizen of McCracken County,

[fol. 15] Kentucky, and well acquainted with the negro citi

zenship thereof; that he will state there are several hun

dred negroes in said county that meet all requirements of

t the law as to qualifications for jurors—

He says he can prove by J. W. Trevathen that he was

deputy circuit court clerk under Frances Allem during the

I years 1928 to 1934; that as such he attended every term of

the McCracken Circuit Court during that time, and that

he never saw a negro serve on a jury in the McCracken Cir_-

■ c-uit Court during that time.

He says he can prove by F. P. Feezor that he is now the

! clerk of the McCracken Circuit Com t and has been such for

the past two years; that he has attended every term of the

McCracken Circuit Court during said time, and that he has-

never seen a negro sit on a jury in the McCracken Circuit

Court during that time; that he is well acquainted with the

negro population of this county and will state that there

are several hundred negro citizens in said county who meet

every requirement of the law as to qualification for jury

service.

He says he can pi’ove by C. B. Crossland, Sr. that he

was Court reporter for the McCracken Circuit Court dur

ing the years 1909 to 1914; that as such he attended every

term of the McCracken Circuit Court; that since_said time

he has been a practicing lawyer at the McCracken County

Bar and has attended-every term of the McCracken Circuit

Court for twenty-seven years, and that during said time

he has never seen a negro set on a jury in McCracken Cir

cuit Court; that he has been Police Judge of Paducah, and

is well acquainted with the negro citizenship of McCracken

County, Ky. and will state that there is now and has been

for several years past,^several hundred negroes that meet

every requirement under the law as to qualification for jury

service.

” [fol. 16] He says that he can prove by Marshall Jones

that he is now the Court "Reporter J or the McCracken Cir

cuit Court and has been such since January 1.1914, and has

attended every term of the McCracken Circuit Court during

that time, and that he has never seen a negro set on a jury

in the McCracken Circuit Court during said time.

He says that he can prove by Professor D. H. Anderson

; that he is principal of the Western Kentucky Industrial

; College, a negro school located in Paducah, McCracken

County, Kentucky and has been such for twenty years; that

he is a negro educator, and is well acquainted with the

negro citizenship of McCracken County, Kentucky, and

will state that there is now and has been for the past twenty

years more than five hundred negroes that meet every re

quirement of the law for qualification for jury service, and

that during this time he has never seen nor heard of a

- negro serving on any jury in the McCracken Circuit Court.

- He says that he can prove by I. N. Boyd that he is a,

negro undertaker in the City of Paducah and lias been such

for the past twenty years, and that he has been a resident

| of Paducah for Forty vearsu that he is well acquainted with

the negro citizenship of McCracken County and will state

that he knows^several hundred negroes in said county that

meet every requirement of the law as ^qualification for

jury service, and that he never saw or heard of a negro

serving on a jury in the McCracken Circuit Court.

[fob 17] lie states that he can prove by K. G. Terrell, a

wholesale grocer of Paducah, that he is 88 years of age,jand

has resided in McCracken County all of his life; that there

,is now and has been during the past fifty years several hun-

12

dred negroes residing in McCracken County who meet every

requirement of the law as to qualificationfor jury service,

and that during the past fifty years he never saw nor heard

of a negro serving either on a Grand or Petit jury in the

McCracken Circuit Court.

P He states that John Counts, 65 years of age, business man,

has resided in McCracken County for the past thirty years ;

that he can prove by him that there are now and have -been

during the time of his residence here ^several hundred

negroes residing in McCracken county who meet every re

quirement of the law as to qualification for jury service, and

that during the past thirty years he never saw nor heard of

a negro serving either on a Grand or Petit Jury in the Mc

Cracken Circuit

He states that he can prove by Henry Houser, ex-jailer

of McCracken county. 75 years of agtn that he- has lived in

McCracken county all of his life ; that there is now and has

been during the past fifty ..years several hundred negroes

residing in McCracken County who meet every requirement

of the law as to qualification for jury service, and that dur-

1 ing the past fifty years he never saw nor heard nr a. negro

serving either on a Grand or Petit jury in the McCracken

| Circuit Court.

f[fo l. 18] He states that he can prove by J^D. Mocquot, at-

\tornev at law. 70 years of age, that he nas lived in" Mc-

Cracken county all of his life ; that there is now and has been

during the past fifty years several hundred negroes resid

ing in McCracken county who meet every requirement of the

law as to qualification for .jury service: that he. the said

Mocquot, has been practicing law in the McCracken Circuit

Court for approximately fifty~years, and that he has at

tended approximately every session of the McCracken Cir

cuit Court during that time, and that he has never seen nor

heard of a negro serving either on a Grand or Petit iurv

in the McCracken Circuit Court.

r He states that E. J. Paxton. 65 years of age, is the owner

and publisher of the Paducah Sun-Democrat, a daily news-

[paper in the city of Paducah, and has resided in McCracken

- county all of his life, and that he can prove by him that there

is now and has been during the past 45 years several hun

dred negroes residing in McCracken county who meet every,

requirement of the law as to qualification for jury service,

* land that during the past forty-five years he never saw nor

13

s

H i -

r e c .

J-

heard of a negro serving either on a Grand or Petit Jury in

the McCracken Circuit Court.

He states that he can prove by Jacob R. Wallerstein, 80

years of age, a Paducah business man for more than fifty

yeais, that there are several hundred negroes residing in

McCracken countv and have been during the past fifty years.

who" meet every requirement of the law as to qualification

for jury service, and that during the past fifty years he

never heard of nor saw a negro serve on a jury either

Grand or Petit, in the McCracken Circuit Court.

[fol. 19] He states that he can prove by M. Marks, a

Paducah business man for over fifty years, that there are

now and have been during that time several hundred negroes

residing in McCracken county who meet e v e r y requirement

for qualification for jury service, and that during said time

Ihe has never seen nor heard of a negro sitting on either a

Grand or Petit jury in the McCracken Circuit Court.

He states that he can prove by Col. Robert Noble, 78 years

of age, capitalist, retired, that there are now and have been

\ during the past fifty years several hundred negroes resid-

ing in McCracken county who meet every requirement for

I qualification for jury service and that during all of said

l time ne nas never seen nor heard of a negro sitting either on

j a Grand or Petit jury in the McCracken Uircuit court..

He states that he can prove by R. L. Reeves, President of

the Peoples National Bank, attorney at law, ex-city at

torney, about 75 years of age, that there is now and has been

for the past fifty years several hundred negroes residing

in McCracken county who meet every requirement for

qualification for jury service, and that during the past fifty

years he has never seen nor heard of a negro sitting on

either a Grand or Petit jury in the McCracken Circuit Court.

He states that he can prove by Jack E, Fisher; attorney at

law, that he was Commonwealth Attorney of the McCracken

Circuit Court for the twelve years immediately preceding

the year of 1928; that he attended every term of the Mc

Cracken ClrcrnlTCourt during that time and that he has

never seen nor heard of a negro sitting on either a Grand or

Petit jury in the McCracken Circuit Court.

:Lfol. 2d] Affiant states that each and all of the foregoing

witnesses are residents of McCracken County, Kentucky, and

within the jurisdiction of this court; that most of said wit

nesses are actually in court to-day, and that if given the op-

| portunity all of the witnesses to the above facts can be pro-

14

cured to give their testimony orally in court in the course

of two hours; that they will testify as indicated herein; that

same is true and will be true when proven; that this motion

and affidavit is not made for delay hut that justice may be

[ done.

Affiant states that the foregoing facts when proved show

; a long continued, unvarying and wholesale exclusion of

negroes from jury service in this county on account of their

race and color; that it has been systematic and arbitrary on

the part of the officers and commissioners who select the

names for jury service for a period of fifty years or longer;

that it is prejudicial to his substantial rights and in violation

of the Constitution of the United States. He therefore asks

the Court to hear the proof upon his motion to set aside the

indictment.

Joe W. Hale.

Subscribed and sworn to before me by Joe Hale this

the 12th day of Oct. 1936. F. P. Feezor, Clerk, Mc

Cracken Circuit Court.

[File endorsement omitted.]

[fol. 21] In Circuit Court op McCracken County

[Title omitted]

Supplemental A ffidavit and Stipulation—Filed October

12,1936

Affiant and defendant Joe Hale, states that since the

preparation of the original affidavit in support of motion to

set aside the indictment in this case, he has learned that in

the April, 1921, term of the McCracken Circuit Court, upon

the trial of a negro in said court upon a minor felony,

charge, the Hon. Wm. Reed, Judge of said court instructed

the sheriff of McCracken to summon from bystanders a

rieg’ro jury to try said case, which was done.

He further states that the names of these negro jurors

were not drawn from the rurv wheel or drum, never having

been placed therein by the jury commissioners, but was a

pick-up jury ordered by the court for this special case, and

that said negro jurors were not regular members of the petit

jury panel for that term of court.

Joe W. Hale.

Subscribed and sworn to before me by Joe Hale this

the 12th day of October, 1936. F. P. Feezor, Clerk,

McCracken Circuit Court.

It is stipulated that this and the original affidavit shall be

considered as evidence.and that the witnesses named therein

would testify as set forth therein.

[fol. 22] It is further stipulated that the Judge of the Mc

Cracken Circuit Court has never at any time Instructed the

Jury Commissioners to exclude the names of negroes from

the Jury lists and Jury drum; and that said Judge is now

serving his 15th year as such Judge. Oct. 12th, 1936.

Holland G. Bryan, Com. Atty. Crossland & Cross

land, Atty. For Deft.

[File endorsement omitted.]

15

In Circuit Court of M cCracken County

[Title omitted]

Motion to Discharge Panel— Filed October 12, 1936

Now comes the defendant, Joe Hale, by attorney, and chal

lenges the entire panel of the jury in this case for cause, and

in support of said motion he refers to and asks to be made a

part hereof the affidavit this day filed on the motion herein

to set aside the indictment.,

Joe Hale, by Crossland & Crossland, Attorneys for

Defendant.

[File endorsement omitted.]

16

[fol. 23] In Cikcuit Court of McCracken County

[Title omitted]

Order A llowing W itness F ees—October 12, 1936

This day the following named persons appeared in open

court and claimed their attendance as witnesses for the Com-

monweath, in the above styled prosecution. Said claims

were allowed as follows:

Ed Kortz .................................................. 1 day $1.00

J. E. L y n n ................................................ 1 “ 1.00

W. E. Bryant ........................................... 1 “ 1.00

Kelly Franklin ......................................... 1 “ 1.00

In Circuit Court of McCracken County

[Title omitted]

Order on I nstructions— October 13,1936

Came the same jury heretofore empaneled herein, and

resumed the trial of this prosecution. At the conclusion^ of

P1aintifF,g flgjdfiBca, the defendant by attorney, offered in-

stmctLoiL-tLA!.’ to find for defendant, and moved the Court

to give same to the jury, to the giving of which the Com-

[fol. 24] monwealth by Attorney, objected, and said objec

tions being submitted to the Court, and the Court being

advised, sustained said objections, and refused to give In

struction “ A ” to the jury, to which ruling of the Court, the

defendant excepts.^/Ai Thmciuiclnsion ..of- abLeyjdenee, de

fendant re-offered Instruction “ A ” and moved the Court to

give same to the Jury, to the giving of which the Common

wealth, by its attorney, objected, and said objections being

submitted to the Court, and the Court being advised, again

sustained said objections, and refused to give Instruction

“ A ” to the jury, to which ruling of the Court the defendant

except^/ The Court then gave to the jury, Instructions Nos.

1 to 9, inclusive, to the giving of each and all of which the

defendant objects and excepts and moved the Court to give

the whole law in the case, and the Court being of the opinion

that he had so instructed, declined to instruct further, to

which the defendant excepts. It is ordered that all of said

Instructions both given and refused by the Court, be filed

and made a part of the record herein.

17

V erdict—October 13, 1936

After argument by counsel, the sheriff was sworn to take

charge of the jury which retired to its room for deliberation

and returned into court the following verdict: “ We, the

jury, find Joe Hale, the defendant, guilty of the first degree

of murder, fix his penalty death in t.he electric chair ”

A. W. Rickman, one of the jury. On motion of defendant by

attorney, the jury was polled, and each juror answered that

it was his verdict.

\ Came defendant by attorney, and filed motion and reasons

1 for a new trial.

The defendant in person and by attorney, waived the

three day stay in jail prior to his sentence.

[fol. 25] In Circuit Court of McCracken County

[Title omitted]

Defendant’s Requested Instruction—Filed October 13,

1936

Instruction “ A ”

The Court instructs the jury to find the defendant not

guilty.

Refused.

[File endorsement omitted.]

In Circuit Court of McCracken County

[Title omitted]

Instructions to Jury— Filed October 13, 1936

Instruction No. 1

Gentlemen of the Jury:

If you shall believe from the evidence in this case, to the

exclusion of a reasonable doubt, that in McCracken County,

2—680

18

Kentucky, and before the finding of the indictment herein,

to-wit, the 1st day of October, 1936, the defendant Joe Hale,

either by himself or together with Prince William Thorpe

and James Gilbert Martin, alias Junkhead, did willfully,

unlawfully, maliciously and feloniously and of his malice

aforethought kill, slay and murder W. R. Toon, by cutting,

thrusting, stabbing and wounding the said W. R. Toon in

and upon the head, body, arms, limbs and person, -with a

knife, a sharp-edged and pointed instrument, a deadly

weapon, from which cutting, thrusting, stabbing and

[fol. 26] wounding the said W. R. Toon did shortly there

after, and within a year and a day and in the Commonwealth

of Kentucky, die, then you will find the defendant guilty and

fix his punishment at death, or by confinement in the peni

tentiary for life, in your reasonable discretion.

Given.

Instruction No. 2

If you shall not believe from the evidence, beyond a rea

sonable doubt, that the defendant Joe Hale has been proven

guilty of murder, as defined in instruction No. 1 above, but

shall believe from the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt

that he did in McCracken County, Kentucky and before the

finding of the indictment herein, to-wit the 1st day of Octo

ber, 1936, without previous malice and not in his necessary

or reasonably apparent necessary self-defense, but in a sud

den affray, or in sudden heat and passion, upon a provoca

tion reasonably calculated to excite his passions beyond the

power of his control, cut, thrust, stab, and kill W. R. Toon,

you shall in that event find him guilty of voluntary man

slaughter and fix his punishment at confinement in the state

penitentiary for a period of not less than two years and not

more than twenty-one years, in your reasonable discretion.

Given.

Instruction No. 3

If you shall believe from the evidence in this case to the

exclusion of a reasonable doubt that the defendant has been

proven guilty, but shall have a reasonable doubt whether

proven guilty as defined in instruction No. 1 or as defined in

instruction No. 2 you will find him guilty of the lesser offense

as defined in instruction No. 2.

Given.

19

Instruction No. 4

If you shall believe from the evidence that at the time

[fol. 27] the defendant Joe Hale, cut, thrust, stabbed and

killed W. R. Toon, if he did do so, he believed and had rea

sonable grounds to believe that he was then and there in

imminent danger of death or infliction of some great bodily

harm at the hands of W. R. Toon, and that it was necessary

or was believed by the defendant, in the exercise of a reason

able judgment to be necessary to so cut, thrust, stab and kill

the deceased in order to avert that danger, real or to the

defendant apparent, then you ought to acquit the defendant

upon the ground of self-defense or apparent necessity

therefor.

Given.

Instruction No. 5

The words “ with malice aforethought” as used in the

indictment and instructions herein, mean a predetermina

tion to do the act of killing without lawful excuse, and it is

immaterial how recently or suddenly before the killing such

predetermination was formed.

Given.

Instruction No. 6

The words “ willful” and “ willfully” as used in the in

dictment and instructions herein, mean “ intentional” not

“ accidental” or “ involuntary” . The word “ feloniously”

as used in the indictment and the instructions herein mean

proceeding from an evil heart or purpose, done with the

deliberate intention to commit a crime.

Given.

Instruction No. 7

The law presumes the defendant to be innocent of any

offense until proven guilty to the exclusion of a reasonable

doubt, and if upon the whole case you shall have a reason

able doubt of the defendant having been proven guilty, or

[fol. 28] as to any material fact necessary to establish his

guilt, you will find him not guilty.

Given.

20

Instruction No. 8

A conviction cannot be had upon the testimony of an ac

complice or accomplices, unless corroborated by other evi

dence tending to connect the defendant with the commission

of the offense, and the corroboration is not sufficient if it

merely show that the offense was committed, and the circum

stances thereof.

Given.

Instruction No. 9

An “ accomplice” within the meaning of these instruc

tions, is one who has been concerned in the commission of

the crime charged, and has either performed some act or

taken some part in its commission, or who, owing some duty

to the person against whom the crime was committed to

prevent the commission thereof, has failed to perform or to

endeavor to perform such duty.

Given.

[File endorsement omitted.]

I n C ir c u it C o u r t of M c C r a c k e n C o u n t y

[Title omitted]

M o t io n a n d R e a s o n s for N e w T r ia l — Filed October 13,1936

Now comes the defendant, Joe Hale, by attorney and

[fol. 29] moves the Court to set aside the verdict of the jury

herein for the following reasons, to-wit:

First. Because the Court erred in overruling defendant’s

motion to set aside the indictment herein.

Second. Because the Court erred in overruling defend

ant’s motion to challenge the entire panel of the petit jury

empaneled in this case.

Third. Because the Court erred in overruling the defend

ant ’s demurrer to the indictment herein.

Fourth. Because the court erred in excluding from the

jury important and material evidence in his behalf.

21

Fifth. Because the Court erred in allowing the Common

wealth to introduce before the jury incompetent, immaterial

and irrelevant evidence.

Sixth. Because the Court erred in refusing to give in

struction “ A ” offered by defendant at the conclusion of the

evidence for the Commonwealth.

Seventh. Because the verdict of the jury is contrary to the

law and evidence herein.

Eighth. Because the Court erred in giving to the jury in

structions 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, & 9, and in refusing to give the

whole law of the case.

To all of which the defendant objected and excepted at

the time, and each and all of which were prejudicial to the

substantial rights of the defendant, and upon this he asks

the judgment of the Court.

Crossland & Crossland, Attorneys.

[File endorsement omitted.]

[fol. 30] lx C ie c u it C o u r t of M c C r a c k e n C o u n t y

[Title omitted]

J u d g m e n t — October 13, 1936

The defendant this day being in open court and being in

formed of the nature of the indictment on the charge of

“ Wilful Murder’ ’, plea and verdict, was asked if he had any

legal cause to show why judgment should not be pronounced

against him; and none being shown, it is therefore adjudged

by the Court that the defendant, Joe Hale, be taken by the

Sheriff and Jailer of McCracken County as expeditiously,

privately and safely as may be, to the State Penitentiary at

Eddyville, Kentucky, where he will be safely kept until the

18th day of December, 1936, on which day the Warden of

said Penitentiary or his Deputy will cause him to be electro

cuted by causing to pass through his body a current of elec

tricity of sufficient intensity to produce death as quickly as

possible and continue the application of such current until

he is dead.

22

Order Overruling Motion for New Trial and Granting

A ppeal— October 13, 1936

Defendant’s motion and reasons for a new trial, hereto

fore filed herein on this date, coming on to be heard, and

the Court being sufficiently advised, overruled said motion

and reasons for a new trial, to which ruling of the Court,

the defendant objects and excepts, and prays an appeal j o

the Court of Appeals which is granted. and~defendanl is

given 60 days in which to prepare and filed his bill of Ex

ceptions and Transcript of Evidence.

Motion to Proceed in F orma Pauperis and Order T hereon

Then came defendant by attorney, and entered motion and

[fol. 31] moved the Court to permit him to prosecute this

Appeal, in forma pauperis, and in support of said motion

filed his own affidavit; and said motion being submitted to

the Court and the Court being sufficiently advised, sustained

same, and it is ordered that he be permitted to appeal this

prosecution in forma pauperis, and the Clerk of this Court

is directed to prepare the record, and the Official Stenog

rapher to transcribe the evidence heard upon the trial of the

case, to be used by him for the purpose of appeal, the same to

be paid for by McCracken County in accordance with Ken

tucky Statutes.

The affidavit filed in the above and foregoing order is as

follows, to-wit:

Affidavit

The defendant, Joe Hale, states that he is a poor person

without money or property and is unable to pay the fees to

the Clerk and official stenographer of this Court for tran

scripts of the record and evidence herein to be used on his

appeal to the Court of Appeals of Kentucky and is unable

to obtain the money to pay said feeds.

He, therefore, asks the court to direct the Clerk of this

Court to make up the record, and the Official Stenographer

to transcribe the evidence heard upon the trial of the case,

to be used by him for the purpose above stated, the same to

23

be paid for by McCracken County in accordance with Ken

tucky Statutes.

Joe W. Hale.

Subscribed and sworn to before me by Joe Hale this

the 12th day of October, 1936. David R. Reed,

Notary Public McCracken County, Kentucky. My

Commission expire- July 31, 1940.

[File endorsement omitted.]

[fol. 32] In Circuit Court of McCracken County

[Title omitted]

O r d e r A p p r o v in g B i l l o f E x c e p t i o n s —November 10, 1936

This day came defendant, by attorney, and tendered Bill

of Exceptions and Transcript of Evidence herein, and en

tered motion and moved the Court to approve and sign same,

and the Court having examined said Bill of Exceptions and

Transcript of Evidence and finding same correct, sustained

said motion, approved and signed same, and it is ordered

that same be filed in duplicate and made a part of the record

herein without being spread upon the Order Book; the origi

nal to be taken to the Court of Appeals, and the carbon copy

to remain on file in the office of the Clerk of this Court.

Clerk’s certificate to foregoing transcript omitted in print

ing.

[fol. 33] In Circuit Court of M cCracken County

Bill of Exception No. 1

Be it remembered that upon the trial of this case the

Commonwealth introduced and had sworn Dr. L eon H igdon,

who testified as follows:

Examined by Hon. Holland G. Bryan:

Q. What is your business or profession?

A. Physician.

Q. Did you know W. R. Toon during his life time?

24

A. Yes sir.

Q. Is he now living or dead?

A. He is dead.

Q. When did he die?

A. I don’t recall the date.

Q. You remember the occasion of his being stabbed?

A. Yes sir.

Q. How long from that time did he live?

A. He lived approximately one hour from the time I

first saw him. He had been in the hospital about fifteen

minutes when I got out there.

Q. Do you know what time you got out there?

A. It was shortly after midnight.

Q. What was the cause of his death?

[fol. 34] A. He died because of hemorrhage; from the loss

of blood from the stab wound in the left arm.

Q. Did you examine his body in the hospital?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Will you describe the wounds he had and the nature

of them?

A. He had three wounds. One wound in the left thigh;

there was a little wound in his left thigh about that broad

(indicating) and about four inches long. We took a groove

director and followed it up. He had a small wound on his

chest, his left chest about the nipped That was not over %

of an inch and it went just to the rib. We could not trace

it into the chest wall. He had one wound on his left arm,

not over % inch wide, and in tracing that it went up this

way (indicating) and when we opened it we found the

Avound had gone through the big axillary artery. This

wound had cut through the axillary artery and had almost

cut it in two. There Avas a little blood clot around the

wound but he had lost considerable blood before he came

to the hospital.

Q. Neither of those A vounds were very large?

A. In our first examination Ave did not think he was badly

injured, but when Ave took this groove director we could tell

the axillary artery Avas almost entirely severed. All three

of the wounds were on the left side of his body.

25

Cross-examined.

By Hon. C. B. Crossland:

Q. How old was Mr. Toon, if you know?

A. I don’t know exactly, he was past 40 years I am sure.

Q. Do you know about his height ?

A. He was about five feet six inches.

Q. Do you know about his weight?

A. I would say he weighed about 160 pounds.

Q. What was the color of his hair?

A. I am not sure of that, I don’t know.

[fol. 35] Q. Did he have light sandy hair?

A. He was a little darker I think, I am not positive about

that.

Q. Did he have his clothes on when you examined him ?

A. Yes sir.

Q. How was he dressed?

A. He had his shirt on when I saw him, his trousers had

been removed in the operating room. He had on his shirt

and underwear.

Q. What kind of shirt did he have on?

A. A light colored shirt.

Q. Did you see his trousers?

A. Yes sir.

Q. What color were they?

A. They were grey looking trousers.

Q. Where they light or dark?

A. I don’t know whether they were light or dark. I recall

seeing the trousers because I helped to examine them.

Q. Was he ever conscious after you reached there?

A. He had one or two periods where I think perhaps he

recognized the members of his family and myself, he called

me “ Doctor.”

Redirection.

By Hon. Holland G. Bryan:

A. Did you notice the cut places in his clothes to see

whether or not they corresponded with his wounds ?

A. We examined them carefully and they corresponded

exactly with his wounds.

Q. The holes in his shirt and trousers ?

A. Yes sir, they were all stained with blood.

26

[fol. 36] Be it remembered that upon the trial of this case

the Commonwealth introduced and had sworn Ed K irk,

who testified as follows:

Examined by Hon. Holland G. Bryan:

Q. Where do you live, Mr. Kirk?

A. 3220 Kentucky Avenue.

Q. What is your business?

A. Mail Carrier.

Q. How long have you been a mail carrier ?

A. About 17 years.

Q. Did you know W. R. Toon during his life time ?

A. Yes sir.

Q. How long had you known him?

A. Ten or twelve years.

Q. Do you remember the occasion of his being stabbed to

death?

A. I remember it.

Q. Was any kind of gathering being held anywhere in

Paducah that night?

A. Yes sir.

Q. What was it ?

A. A K. C. picnic.

Q. Where was that held?

A. At 28th and Kentucky Avenue.

Q. Are you a member of the K. C. (Knights of Colum

bus)

A. I am not, but I was working out there.

Q. You say you were working out there at this picnic?

A. Yes sir.

Q. What kind of work did you do out there ?

A. I had a bottle rack.

Q. I believe you say you knew Mr. Toon?

A. I did.

Q. Was he out there that night?

A. He was.

[fol. 37] Q. Do you know what time he came out there.

When did you first see him?

A. I don’t — when was the first time I saw him, I know

when was the last time I saw him.

Q. When was that?

A. I checked out of my stand ten minutes after ten and

I carried my things over to my car, and then I went over

27

to the meat stand to get some meat, and he was standing

there and I spoke to him.

Q. You closed your stand ten minutes after ten?

A. Yes sir.

—. Then you went over to the stand to get some meat

and Mr. Toon was there?

A. Yes sir, and I spoke to him.

Q. Do you know whether or not he left there?

A. I don’t know, he was still standing there when I got

my meat and left.

Q. Did you see him around there at this gathering that

night ?

A. I saw him two or three times that night.

Cross-examined.

By Hon. C. B. Crossland:

Q. You have known Mr. Toon for ten or twelve years?

A. Something like that.

Q. What was his height ?

A. About as high as his brother, about the same height

or build, maybe a little heavier set.

Q. About how much would he weigh?

A. I don’t know, I am not very much of a judge of a

man’s weight.

Q. He would weigh about 180 or 190 pounds ?

A. I don’t know his weight, I am not very much of a

judge of a man’s weight.

Q. What was the color of his hair?

A. He was slightly bald-headed.

[fol. 38] Q. How was he dressed?

A. He only had on a light shirt, no coat.

Q. And light pants?

A. I never paid any attention to his pants.

Q. Was he bare headed?

A. He was bare headed when I saw him.

Be it remembered that upon the trial of this case the Com

monwealth introduced and had sworn J. E. L inn , who tes

tified as follows:

Examined by Hon. Halland G. Bryan:

Q. Where do you live, Mr. Linn?

A. At 25th and Kentucky Avenue.

28

Q. What is your business or profession?

A. I work on the rip track, am car repairer and inspector.

Q. Did you know W. R. Toon in his life time?

A. I have known him around sixteen years.

Q. Do you remember the night he was killed?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Where were you that night about eleven o ’clock?

A. I was working with him about that time.

Q. You mean you was working on him at the hospital?

A. No sir.

Q. Where did you first get in company with him that

night ?

A. He passed me before I got to Tenth Street, and when

he got to Tenth Street where he should have stopped he

did not stop but went on through.

Q. How were you traveling?

A. I was on a bicycle.

Q. On what street?

A. On Kentucky Avenue.

Q. Between 9th and Tenth Streets?

A. Yes sir, about the length of this building before I got

[fol. 39] to 10th street.

Q. You were between W ater’s restaurant and 10th

street?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Which way were you going?

A. I was going the same way he was going.

Q. He overtook you and passed you?

A. Yes sir.

Q. At what speed was he traveling?

A. At an ordinary speed.

Q. In his automobile?

A. Yes sir.

Q. What attracted your attention to him?

A. He was supposed to stop at 10th street, hut he did

not stop, he went on through.

Q. Did you notice that it was Mr. Toon?

A. No sir, I did not know who it was.

Q. What time of night was that?

A. It was about five, six or seven, possibly ten minutes

to eleven o ’clock.

Q. Five or ten minutes before eleven o ’clock?

A. Yes sir.

29

Q. When he headed on through this boulevard at 10th

and Kentucky Avenue what happened?

A. His car kept on bearing over to the left when he should

have stayed on his side of the street, and it went on and

hit this pole and went between this pole and the building

out there.

[fol. 40] Q. Between this warehouse and the laundry?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Did you go on up there ?

A. I stopped and watched it.

Q. What did you do after his car hit this building ?

A. I stood there a few minutes and a big negro came

along and I hallowed to him and said “ Let’s go over and see

if that fellow is drunk or hurt” . We went over there and I

walked up near the car and said, “ Mister can I be of any

help” and nobody replied and I called the second time and

nobody replied, and I said to this negro, “ That is a hunch

of drunks, let’s go up and see how badly they are hurt,” and

Toon was in the car in this position (indicating stooped over

the steering wheel) and the engine was still running. I

straightened him up and said “ Toon—Toon is this you”

and he said “ Yes” and he had some kind of stuff on his face

where he had thrown up, and that excited me, and I took my

finger and wiped it off of his face, and I said, “ You have

hurt yourself” I never knew him to drink and — not think

about him being drunk------

Objection by Attorney for Commonwealth.

Objection sustained by the Court.

Exception by Attorney for Defendant.

A. Well, I straightened him up and the blood just gushed

out of his left arm or side, and then some police came up

there and I told them to call the law and they did, and when

they flashed their light on him his shirt was all bloody and

I said, “ Go and get Terrell” , and he said he did not know

where he lived, and I said, “ I will go get him” and we

rushed out to Terrell’s house and he was in bed and I told

him about it and he put on some clothes and his shoes and

we lit out down there and somebody had already taken him

to the hospital, and when I got out there Toon was in a room

and they was trying to sew him up as best they could.

30

[fol. 41] Cross-examined.

By Hon. C. B. Crossland:

Q. You was going west on Kentucky Avenue?

A. We were both traveling in the same direction.

Q. That was after he had passed 10th street that he ran

into this pole ?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Between 10th and 11th street?

A. Yes sir.

Be it remembered that upon the trial of this case the

Commonwealth introduced and had sworn Terrell Toon,

who testified as follows:

Examined by Hon. Holland G. Bryan:

Q. You are Mr. Terrell Toon?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Where do you live ?

A. 435 South 19th Street.

Q. How long have you lived in Paducah?

A. Eighteen years.

Q. Before that time where did you live?

A. Out in McCracken County on the Contest Road.

Q. Out near St. John?

A. I was born at Fancy Farm and moved out there near

St. John.

Q. What relation was W. R. Toon to you?

A. Brother.

Q. What was his age ?

A. 48 years old.

Q. What family did he have?

A. A wife, two daughters and two small sons.

Q. Where did he live?

A. 2022 Kentucky Avenue.

Q. Where did he work?

[fol. 42] A. For the Illinois Central Railroad Company.

Q. What kind of position did he have ?

A. He was lead man over the switchengine department.

Q. Did he have anybody working under him by the name

of Powell ?

A. A colored switchman who worked with the crew by the

name of Jim Powell.

31

Q. Do you know what kind of car Jim Powell drove?

A. A big Hupmobile.

Q. Do you remember the time your brother was killed?

A. Yes sir.

Q. What day of the month was that?

A. A ugust 18th.

Q. Your brother was a member of the Catholic Church?

A. Yes sir.

Q. How long had he belonged to it ?

A. All of his life.

Q. Did the Knights of Columbus have a picnic that night?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Do you know how long your brother was out there?

A. I was out there early but I went home before 7 :30.

Q. Was anything else going on that night by which you

can fix the time ?

A. The reason I came home at that time was in order to

get Joe Louis-Sharkey fight, which was to be at 8 o ’clock.

Q. You heard the Joe Louis fight that night?

A. Yes sir.

Q. What time of the night did you learn of your brother’s

condition ?

A. We had company that night listening to the fight with

us. After we had retired a few minutes after ten o ’clock,

[fol. 43] we were in bed and somebody came up on the porch

and knocked on the door and asked if I was there------

Objection by Attorney for Defendant.

Q. Just about what time was that ?

A. At that time it was around 10:30 or later, because we

had gone to bed. Our company stayed until ten o ’clock.

Q. After you received that information where did you go?

A. I went with Mr. Kirk, they said his name Avas, back to

the wreck and when we got there they told me they had

taken him over to the hospital, so this man carried me over

to the hospital.

Q. Your brother Avas there when you got over there?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Did he ever regain consciousness sufficient to tell you

Avhat happened?

A. No sir.

Q. How long did he live?

A. He died at tAvo o ’clock, sometime after tAvo o ’clock.

32

Q. Mr. Toon what kind of automobile was your brother

driving?

A. A 1934 model Chevrolet.

Q. Did you look in this car that night or the next day?

A. Yes sir that night and also the next day.

Q. Describe the inside of that car to the jury?

A. The front seat of the car, on the left hand side, where

he sat was all clotted with blood, and the bloJd was about

[fol. 44] three inches high up here (indicating). The blood

had run down in the car. It had run clear across the floor

mat off on the fender and dripped on the ground. There

was blood spattered on the wind shield, the dash of the car

and on the door post and on the side of the door of the car.

Q. You say blood had dripped out on the ground from

the car?

A. Yes sir.

Q. That was at 10th and Kentucky Avenue ?

A. About 60 feet the other side of 10th and Kentucky

Avenue.

Q. Was there any blood on the outside of the fender?

A. No sir.

Q. Was there any blood on the outside of the door or any

where else except what had run out there from the inside of

the car?

A. No sir.

Q. Did you examine your brother’s body?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Tell the jury where the wounds were ?

A. The wound was up in here, that was the fatal wound,

so the Doctor said——

Objection by Attorney for the Defendant.

By the Court: The Doctor has described the wounds.

Q. You heard the Doctor describe those wounds, is that

correct?

[fol. 45] A. Yes sir.

Q. Just stab wounds?

A. Yes sir.

Cross-examined.

By Hon. C. B. Crossland:

Q. How high was your brother?

A. Five feet seven inches, or something like that.

33

Q. Do you know how much he would weigh?

A. About 168 or 170 pounds.

Q. What was the color of his hair?

A. Well it was black mingled with gray.

Q. Did you see his clothes that night?

A. I helped to take them off of him.

Q. What clothes did he have on?

A. A light shirt and a pair of gray summer weight

trousers.

Q. Did he have on a hat?

A. No hat.

Be it remembered that upon the trial of this case the Com

monwealth introduced and had sworn Buddy Mercer, who

testified as follows:

Examined by Hon. Holland G. Bryan:

Q. Mr. Mercer, you are a member of the Paducah Police

Department ?

A. Yes sir.

[fol. 46] Q. And were you such on the night of August

18th?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Were you riding in one of the patrol cars ?

A. Yes sir, Mr. Green and I.

Q. Did you know W. R. Toon in his life time?

A. No sir.

Q. Were you one of the officers who came up to the scene

of this accident ?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Tell the jury what you discovered when you arrived on

the scene?

A. When we got there the car was up against this tele

phone pole, and I asked somebody if it was a drunk and they

did not seem to know. I looked in the car and he was stooped

over the steering-wheel. I threw my flash light in the car

and then walked around to the side where he was and opened

the door and threw my light in again and I saw that blood

was running out of his arm and it was all over his clothes. I

then telephoned in for the ambulance and it got out there in

five or six minutes and they took him to the hospital.

3—680

34

Q. Do you know what time it was when you got out there ?

A. About ten minutes after eleven o ’clock. We were

down at 9th and Kentucky Avenue, and got some water and

sat there a minute or two and then we got this call.

Q. You drove from 9th Street down to 10th street?

A. Yes sir.

[fol. 47] Be it remembered that upon the trial of this case

the Commonwealth introduced and had sworn Leo Poat,

who testified as follows:

Examined by Hon. Holland G. Bryan:

Q. Where do you li/e, Mr. Poat?

A. At 2008 Broadway.

Q. What is your business ?

A. Traveling Salesman.

Q. Were you any relation to W. R. Toon?

A. By marriage, he was my brother in law.

Q. Do you remember the occasion of his death, the night

he was killed?

A. I do.

Q. Were you out at this picnic that night?

A. No sir I was not out there.

Q. When did you first receive information that anything

had happened to your brother-in-law ?

A. About four o ’clock the next morning, I was down at

Ripley, Tennessee.

Q. Did you immediately come up here then?

A. Yes sir, I got here about noon.

Q. Did you then take possession of Mr. Toon’s clothes?

A. I did.

Q. Do you have them now?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Has there been any changes made in them since that

time?

A. There has not been.

Q. Will you show those clothes to the jury?

A. Well here are his shoes and socks.

[fol. 48] Q. Just pass them to the jury, one at a time and

let them see them.

A. There is no blood on either of them. This is his shirt,

it is as bloody now as it was then. It shows the stab wounds.

35

His shirt was cut off of him at the hospital, but under his

arm there is a hole showing where the knife went in. I have

his trousers here and they show that no blood run below his

knees, all of the blood run down into his lap. There is one

stabbed place in his trousers. This is his underwear and it

is all bloody. (Showing the jury his clothes.)

Q. How old was your brother-in-law?

A. I think he was 44 years old.

Q. He was between 40 and 50 years old?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Do you know whether or not he lived in McCracken

County and in Paducah all of his life ?

A. He was born in Graves County and came to Mc

Cracken County a number of years ago.

Q. What kind of work did he do?

A. He worked for the Illinois Central Railroad Company

in the yards, he had charge of the switch engine and switch

ing crew.

Q. Do you know who his employes were. Do you know

whether or not he had a colored man working for him by the

name of Powell?

A. Yes sir, Jim Powell.

Q. Do you know where Jim Powell lived?

A. I did not until this took place. I know where he lives

now.

[fol. 49] Q. Where does he live now?

A. At 8th & Ohio streets, I believe. I did not know where

he lived until after this took place. His brother and I were

trying to trace his movements and it was a thought of his

that he had probably gone to see this colored man------

Objection by attorney for defendant.

Objection sustained by the court.

Exception by attorney for commonwealth.

Q. In trying to trace his movements you located this

colored man?

A. Yes sir.

Q. And he lived where?

A. I believe it was at 8th & Jones street.