Terrazas v. Clements Court Opinion

Unannotated Secondary Research

January 4, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Terrazas v. Clements Court Opinion, 1984. ad83e5dc-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c5ef45b-c8e8-47b6-aaaa-0cc3f38af3c0/terrazas-v-clements-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

t

\

li

E

ir

h

i

r

I

I

F

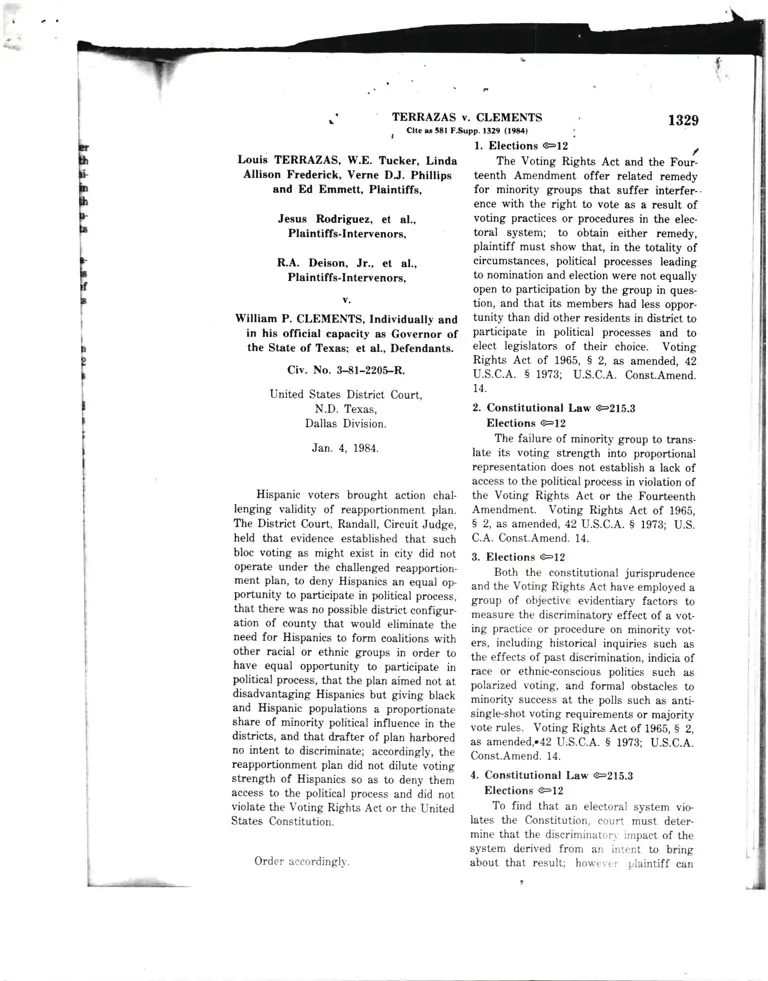

Louis TERRAZAS, W.E. Tucker, Linda

Allison Frederick, Yerne DJ. Phillips

and Ed Emmett, Plaintiffs,

Jesue Rodriguez, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors,

R.A. Deison, Jr., et al.,

Plaintiffs-I ntervenore,

v.

William P. CLEMENTS, Individually and

in his official capacity as Governor of

the State of Texas; et al., Defendants.

Civ. No. 3-81-2205-R.

United States District Court,

N.D. Texas,

Dallas Division.

Jan. 4, 1984.

Hispanic voters brought action chal-

lenging validity of reapportionment plan.

The District Court, Randall, Circuit Judge,

held that evidence established that such

bloc voting as might exist in city did not

operate under the challenged reapportion-

ment plan, to deny Hispanics an equal op-

portunity to participate in political process,

that there was no possible district configur-

ation of county that would eliminate the

need for Hispanics to form coalitions with

other racial or ethnic groups in order to

have equal opportunity to participate in

political process, that the plan aimed not at

disadvantaging Hispanics but giving black

and Hispanic populations a proportionate

share of minority political influence in the

districts, and that drafter of plan harbored

no intent to discriminate; accordingly, the

reapportionment plan did not dilute voting

strength of Hispanics so as to deny them

access to the political process and did not

violate the Voting Rights Aet or the United

States Constitution.

Order eecordinglv.

,

TERRAZAS v. CLEMENTS

, CltGuStl FSupp. l!2.!) (t9&0)

1329

l. Elections @12 /

The Voting Rights Act and the Four-

teenth Amendment offer related remedy

for minority groups that suffer interfer-.

ence with the right to vote as a result of

voting practices or procedures in tle elec-

toral system; to obtain either remedy,

plaintiff must show that, in the totality of

circumstances, political processes leading

to nomination and election were not equally

open to participation by the group in ques-

tion, and that its members had less oppor-

tunity than did other residents in district to

participate in political processes and to

elect legislators of their choice. Voting

Rights Act of 1965, S 2, as amended, 42

U.S.C.A. 5 1973; U.S.C.A. Const.Amend.

L4.

2. Conetitutional Law e215.3

Elections @12

The failure of minority group to trans-

late its voting strength into proportional

representation does not establish a lack of

access to the political process in violation of

the Voting Rights Act or the Fourteenth

Amendment. Voting Rights Act of 1965,

5 2, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. 5 19?3; U.S.

C.A. Const.Amend. 14.

3. Elections el2

Both the constitutional jurisprudence

and the Voting Rights Act have employed a

group of objective evidentiary factors to

measure the discriminatory effect of a vot-

ing practice or procedure on minority vot-

ers, including historical inquiries such as

the effects of past discrimination, indicia of

race or ethnic-conscious politics such as

polarized voting, and formal obstaeles to

minority success at the polls such as anti-

single-shot voting requirements or majority

vote rules. Voting Rights Act of 196b, S 2,

as amended,.42 U,S.C.A. 5 l9?3; U.S.C.A.

Const.Amend. 14.

4. Constitutional Law e215.3

Elections @12

To find that an electoral system vio-

lates the Constitution, cour+. must deter-

mine that the discriminat(,r\ inrpact of the

system derived from an irlr'nt to bring

about that result; hou'ei t: plaintiff can

L .-.,--, - .

581 FEpERAL SUPPLEMENT1330

establish a violation of the Voting Rights

Act by showing a discriminatory result,

which in turn can be proven through the

aggregate of the objective factors' Voting

Rights Act of 1965, S 2, as amended, 42

U.S.C.A. 5 19?3; U.S.C.A. Const.Amend'

14.

5. B1"s1gen5 6=12

When a minoritY grouP contends, un-

der the Voting Rights Act, that electoral

system disenfranchises them because their

race or ethnicity has decisive political sig-

nificance, objective factors provide indicia

of how great a role race or ethnicity plays

and how severe are the probable effects,

and they offer a framework to distinguish

unlawful electoral system in which consid-

erations of race of ethnicity pervade poli-

tics from a permissible electoral system in

which racial and ethnic composition of the

elected body simply does not mirror that of

its constituency. Voting Rights Act of

1965; S 2, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. S 19?3.

6. Constitutional Law o-225.3(l)

Elections G=l2

Under the constitutional test for voting

dilution cases, court must go beyond the

objective factors to assure itself that

record independently satisfies the general

equal protection standard that a facially

neutral rule must derive from discriminato-

ry purpose. U.S.C.A. Const.Amend' 14'

7. B1ug1i6ns @12

Provided that the districts are equally

apportioned, single-member districts do not

obviously dilute voting strength; only ref-

erence to minority composition of the dis-

triet and the manner in which the district

lines are drawn can change such plans into

devices with discriminatory results' Vot-

ing Rights Aet of 1965, 5 2, as amended, 42

U.S.C.A. S 19?3; U.S.C.A. Const'Amend'

14.

,. g1""1ien5 el2

A lack of proportional representation

has no independent constitutional or statu-

tory significance, and a court-ordered reme-

dy for voting dilution would not necessarily

warrant the design of a plan that ensures

proportional rePresentation.

g.'Elections c-I2

Reapportionment is a political process,

and there is nothing illegitimate about con-

sidering the political consequences of a re-

districting plan; tenuousness, i.e., pretext,

cannot be established as a factor militating

against the plan simply by pointing out

that the plan has political consequences

that the drafters contemplated' Voting

Rights Act of 1965, S 2, as amended,, 42

u.s.c.A. s 19?3.

10. States c=27(3)

State can take race into account in

drawing legislative districts to comply with

the Voting Rights Act. Voting Rights Act

of 1965, S 2, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A.

s 1973.

11. Blsslisns cp12

In evaluating totality of circumstances

to determine whether reapportionment plan

so dilutes voting strength of minority vot-

ers that they have lost their ability to par-

ticipate politically, the court considers sev-

eral issues: the feature of the electoral

system that allegedly hinders minority vot-

ers in their attempt to achieve a stronger

political voice; extent to which ethnicity

determines outcome of electoral contests;

the result that the districts aehieve; and,

for the purposes of the constitutional chal-

lenge, the intent behind the line drawing.

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 5 2, as amend-

ed, 42 U.S.C.A. S i973; U.S.C.A. Const'

Amend. 14.

12. Constitutional Law @225.3(l)

g1"61isns €=12

Where the absence of proportional rep

resentation results simply from the loss of

elections rather than from a built-in bias

against a minority group, that group's vot-

ing strength has not been cancelled out in

any constitutional sense, and the.same re-

sult obtains under the Voting Rights Act'

Voting Rights Act of 1965, S 2, as amend-

ed, 42 U.S.C.A. 5 1973; U.S.C.A' Const'

Amend. 14.

13. Constitutional Law €=225.3(3)

MuniciPal CorPorations c=80

Evidence in Voting Rights -{ct suit es-

tablished that such bloc voling as mrll

el

le

pr

p(

di

t}

w

v

tl

H

b,

ly

oi

p(

R

A

s

tt

ti

il

S

3

B

3

S

L

A

I

I

c

I

(

I

s

I

I

(

I

I

- -- .-;+l1*-jir

- *-

"hnnn.e,zes v.'cl,Elfi ENTS

Judges.

1331

exist in citv did not*operate J:::'$:*'ffiX?lrm-on' R' {"y'George'

Graves'

lenged reapportionm",i';i;;-; q"1v H5- Doughertv' Hearon & Moodv' Austin' Tex''

oanics equal oppo*oniif to p""titip"tt in for Jefendant Chester R' Upham'

frtiticat pro""r., ttut there was no possible Bob Slagle, III, pro se'

il.t"i"t configuration that would eliminate

Cullen Smith,

',arry

O. Brady, Naman,

the need foiHispanics to form coalitions Hr"*"fi, S,nii', &.,*",bavid Guinn, Michael

with other racial groups to haYe equal op

frtor"irorr, Baylor Law School, Waco, Tex',

portunity to participate in political proce.ss' i"r-a"f*a""i David Dean.

lhat the-ptan did not aim at disadvantaging

Hispanics, and that diafter of plan har- William French Smith' U'S' Atty' Gen''

borednointenttoaiscrlminate;according-PaulHancock'RobertS'Berman'DavidS'

ly, the plan did not air-r-t uoting strengih conningi,arn, III, u.s. Dept. of Justice,

ofHispanicsSoaSt0denythemaccess.towast,in'gton,D.C.,amicuscuriaeDept.of

oofiil.if oto.ess and did not violate Voting Justice'

'mtSi,.jr:'rfiI'Iill;"1"i;-rtl6lf

Berore RANDALL, circuit Judge, and

S 19?3: U.S'C.A. Const'Amend' 14' SANDERS and BUCHMEYER' District

Thomas G. Crouch, Crouch & Jones' Pa-

tricia A. Hill, Dallas, Tex', for senate plain-

tiffs (CA 3-81-1946-R)'

John N. McCamish, Jr', Pat DeelY'

McCamish, Ingram, Martin & Brown' Inc''

irn ,q'nto"io, iex., for house plaintiffs (CA

s-8i-2205-R).

Randall B. Strong, Daniel R' Jackson'

BayL*r, Tex., for Baytown plaintiffs (CA

3-81-2263-R).

Joaquin G. Avila, Jose Garza' Norma V'

Solis, iudith A' Sanders, Mexican American

l,egal Defense and Educational Fund' San

.g,niorio, Tex', Albert H' Kauffman' Dallas'

C"*., Vit.nu S. Martinez, Morris J' P4l:t'

ftf"*i."n American Legal Defense and Edu-

."lionut Fund, San Francisco' Cal'' for

MALDEF intervenors'

J. Richie Field, Crews, Field' Steele &

Page, Conroe, Tex', for Montgomery Coun-

ty intervenors.

David R. Richards, Executive Asst' Attv'

Gen., State of Tex', Steve Bickerstaff' C'

noU"tt Heath, Martha E' Smiley' Bicker-

staff, Heath & SmileY, Richard

''

g"''

iII, 6r"y, Allison & Becker, Austin' Tex''

i"t a"f""a"nts Mark White' William P'

Clem"nts, William P' Hobby' Bill Clayton'

Bob Bul)ock and Bob Armstrong'

l. Terrns dcfined in our opinion of March 24'

^'r"s: "'i, ;:,;;. ' Clcmenrs' 537 F'supp'

^514

iX.O.f.. , itat denied, 456 U'S' 9o2' 102 S'Ct'

RANDALL, Circuit Judge:

ln this opinion, we decide whether the

State of Texas has violated section 2 of the

Voti"g Rights AcL, 42 U'S'C'A' 5 1973

(W".iSrpp-.f983), or the fourteenth amend-

ment to the United States Constitution in

Ir"*irg the districts to elect members of

it. t.iut House of Representatives from

Oatta. County. Specifically, we consider

the contention of a group of hispanic voters

(the "MALDEF Intervenors") t that split-

iine tt e Dallas hispanic population int'o

if,rZ" ."putute districts cancelled out its

voting strength. Only the seventeen

gor.i ai.tti.ti in Dauas County created by

the State's 1983 reapportionment plan (the

ii1983 Hou." plan"), see Acl of May 20'

1983, ch. 185, igEB Tex'Sess'Law Serv' ?56

(Vernon), are direetlY at issue'

I. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND.

Originally, this action encompassed chal-

lengei by a variety of parties to the reap-

poriionr*rt plan (the "LRB House plan")

ior the Texas House of Representatives

"aopt"a

in J981 !y tt'e l'egislative Redis-

triciing Boa-rd (ttte "LRB")' On November

O, fgAi, the House Plaintiffs filed suit in

the United States District Court for the

W"stern District of Texas' The complaint

1745,72l.8d.2d 158 (1982)' u'ill be used herein

as therein defined'

J

-_----

t:*

i

581 FEDERAL SUPi'LEMENT ,r332

named as defendants various Texas oublic

officials-the Governor, the Li[utenant

Governor, the Secretary of State, the Attor-

ney General, the Speaker of the House of

Representatives, the Comptroller of public

Accounts and the Commissioner of the

General Land Office (collectively, the

"State Defendants"Falong with the chair-

men of the State Democratic and Republi-

can Parties. Allegedly, certain district

lines in the LRB House ptan deliberately

discriminated against black, hispanic and

republican voters.

The aetion was transferred to this Court,

and consolidated with two other aetions: a

parallel suit contesting the Senate reappor-

tionment plan (the "LRB Senate plan',) and

a separate attack on the LRB House plan

filed by the Mayor and the City of Bay-

town, Texas ("Baytown"). This Court also

allowed two other groups of Texas voters

to intervene. On January 4, 1g82, R.A.

Deison, Jr. and other individuals, all claim-

ing to reside in Montgomery County, Texas

("Montgomery County"), entered the Sen-

ate and House eases to raise constitutional

challenges. On January 6, 1982, the MAL

DEF Intervenors joined the Senate and

House actions to assert causes of action

under the constitution and section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act. The early history of

these proceedings and a summary of the

claims of each party appear in our earlier

opinion, Terrazas a. Clemen.ts,58? F.Supp.

514 (N.D.Tex.), stay denied,4b6 U.S. 902,

102 S.Ct. 1745, 72 L.Ed.2d 158 (1982), and

will not be repeated here.

During the course of these proceedings,

the Department of Justice, on January 24,

1982, objected to the LRB Senate and

House plans under section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.A. S 19?Bc (West

Supp.1983). The plans were thus rendered

unenforceable. Until the Department of

Justice precleared the reapportionment

plans, the parties'constitutional and statu-

tory challenges remained nonjusticiable;

thus, the progress of this litigation was

suspended. When the Department of Jus-

tice objected to the LRB Senate and House

plans, this Court had alreadv conducted a

hearing, on Januan' 18-23, 1982. which ad-

dressed the merits of those plans. We

gonducted a second hearing on Mafch 1-2,

1982, to reconsider those plans, along with

other plans submitted by various parties, in

order to select aceeptable temporary plans

under which to conduct the 1g82 Texas

eleetions. On March 11, lg82, this Court

installed the LRB Senate plan and a modi-

fied version of the LRB House plan as

temporary courtordered plans. The lgg2

Texas elections were held under the tempo

rary plans.

In our opinion explaining the adoption of

the temporary plans, this Court urged the

Texas Legislature to adopt procedures to

resolve the Department of Justice,s objee-

tions to the LRB plans. Terrazas o. Clem-

ents, 537 F.Supp. at 548. Ultimately, on

May 16, 1983,, the Texas Senate approved a

new Senate plan (the "1g88 Senate plan,,),

and, on May 20, 1983, the Governor signed

a bill adopting the 1988 House plan. The

State submitted the 1988 plans to the De-

partment of Justice; on August 1, lggg,

the Department precleared the 1g8B House

plan and on September 6, 1988, the Depart-

ment precleared the 1983 Senate plan, thus

freeing this Court to consider whatever

issues remained outstanding.

On September 21, 1983, this Court direct-

ed the parties to file statements identifying

the issues still in controversy. The order

set out a schedule for submitting briefs

and proposed findings. Although we be-

lieved that the action could be determined

on the basis of the previous record, we also

extended an opportunity for an additional

hearing, but required proffers of anticipa-

ted evidence from any party who believed

that the record required further develop

ment. The schedule was to culminate in

oral argument on November 21, 1g88.

The response to this order demonstrated

that only the MALDEF Interienors sought

an adjudication of constitutional or statuto-

ry elaims relating to the 1g8B House plan.

Although the Senate Plaintiffs requested

rulings and a hearing on the 1988 Senate

plan, the House Plaintiffs filed nothing.

Bavtou'n, which had partieipated in the

-,

TERRAZAS v. CI.EMENTS 1333

i

)

t

i

Cltc r. 361 F.SuPP. 1329 (r9&l)

January, 1g82 hearing, likewiJe failed to claim concerning thd West Texas districts

file a statement of issues, a brief or pro- and supplemented the record only as tn the/

po."a finaingt' Montgomery County not allegedly discriminatory results of the Dal-

only failed to respond to this Court's order' las County House districts'

Uu[ trad also failed to appear at.any hear-

Briefing preceded and fol]owed the No-

*-^;'l;:

;::f :f i.]TIi,j''J**,o," ffi *jt Hf,ffiil11;;:*f #"";;ii

and the MALDEF Intervenors, we sched-

addressed the constitutional and statutory

uled an evidentiary hearing for Novembet

"rgr."nt".

Although certain districts in

?li,J',ih$ #x'J:i";'rll:J"Ht S:,:[ tt'i tto"" pran have been artered since the

Plaintiffs sought an adjudication of the LRB originally drew the lines in 1981' the

lawfulness of the entire 1983 Senate plan' Dallas districts have remained unchanged'3

and, at least initially, the MALDEF lnter- Thus' on three occasions-at the January'

venors asserted that the House districts for 1982 hearing on the merits' at the March'

West Texas in the vicinity of Del Rio, as 1982 hearing on temporary plans' and at

well as the Dallas Co"rty-hi.tricts, violated the November, 1983 hearing addressed pri-

the constitution and section 2 of the Voting marily to section 2 of the voting Rights

Rights Act.z Act-we have heard evidence on the pur-

onthemorningofthehearing,theis.poseandeffectoftheDallasdistricting.

SUES NATTOWEd fUTthCT. ThE HOUSC ANd II. THE DALLAS COUNTY DISTRICTS.

Senate Plaintiffs appeared at the hearing

and offered a stipulation to dismiss them Before we consider the merits' a review

from the action. We accepted the stipula' of the Dallas County districts will place the

tionand,onDecember22,lgsS,enteredxparties'claimsinperspective'Thisreview'

consentdecreeestablishingthelg8Ssen-whichwillcomprisefindingsoffact'will

ate plan ". ti,"

p.r*un.nt-plan for Texas set forth the following: a description of the

Senatorial elections. fne ViRt OpF Inter- county population, a description of the dis-

venors, on the other i,and, auanaoned their tribution of the hispanic population within

2. The MALDEF Intervenors stated that the fol- West Texas result in a discriminating [sic]

lor.l'ingissuesoffactandlauremained:impactontheMexicanAmericanvotersof

A. rssues or Fact

-,.., ": ::-_",,."". ilifir"i:4,';'^:l'8";::: ;'$;T

2 or thc

1. Whether the totality of circumstances

regarding T.*". uor"r.lihtp"*nuti'" ttitl 2' whether the Texas House of Represent-

DistrictsinDallasCounryresultsintheinabil-atir,e[sic]DistrictsforDallasCountl'andz,or

ilv of Mexican'Americans in Dallas County to West Texas dilute Mexican American voting

elect candidates of their choice to the Texas strengrh in those respective areas in violalion

kgisrature.

rrsrr L,rurLr-rv "-

":^-"

of the t+th Amendmenr to the United States

2'Whetherthelg83TexasHouseofRep.Constilution.

ff:::'$,i;"J,?' il:'li,:T :e!1 {iii',.1i.';i.' l# ?::',T:: :' l:Y, J H :5;l; 3;;

ts1i,"1'al$,;:' T.:'*',

American voters rn

l,j{*l*:iJ+:f*g:li:f :.',:: ff:'-;

3. Whther [sic] the totality of circumstanc-

es regarding r.*u, io"t of Representatiue (Veinon Supp'1982)' but the Texas Supreme

[sic] Districts for the Del Rio'/Wesi Texas area ioutt strttck dou'n the plan as violating Tex

results in the inability of Mexican Americans Const' art'.Ill' $ 26' u'hich prohibits the unnec-

in the Del nioZW"r, i.i.. ,.." ['e,f"tit'"ai essarv splitting of counties' Clements v Valles'

dates of their choice to the Texas Legislature 620 S'W'2d l12' 11+15 (Tex'1981)' The LRB

4.Whetherthelg83TexasHouseofRep.thendreu.thcdistrictsthatgaverisctothis

resenrative t.i.t

'6iltri.t. f". thc D;l litigation' This Court temporarill' adopted thc

Rio,/West Texas area u'ere adopted u'ith the LR-B Housc plan rvith minor modifications 10

intentofdiscriminatingagainslMcxtcanthedistricrsinlwocountiesafterlhcDe}rarl.

American voters of Wesl Texas. nlenl of Juslic' obiected lo the original l-RR

B. Issues of Lau,

Yrcsr rs^al

Housc plan. 'Jr! las-i ll.rrsc pla:r cQ:rsisi' ol

l.WhethertheTexasHousco[Represcnt.thcLR-R}lt,us.P)allrvithtlrcc(,Lii.i.i)rdt.r(d

ative [sic] Disrricts for Dallas Countl and''or -n6 1;srlirrrr'

I

I

t

I

I

I

I

I

i

i

i

I

Ir

I

r

i

t

I

)

J

i

;

t

:

t

e

1334

the county and a description of thq0ffect

of the past, present and proposed district-

ing plans on Dallas County's hispanies.

A. Dallas County and its Hispanic

Population.

As in the State of Texas generally, the

population of Dallas County grew between

the 1970 and 1980 censuses. The 1970

county population of t,327,320 had, by

1980, grown to 1,556,390. The rate of

growth in the county of 17.3%, however,

lagged behind the 27.l% rate of growth in

the State as a whole. Aecordingly, where-

as the 1970 districting plan had allocated 18

districts to Dallas County, Dallas County's

share of the 1980 State's House of Repre-

sentatives districts declined. Thus, a "one-

man, one-vote" reapportionment in 1980

would entitle the county to only 16.4 dis-

tricts.{ In light of the Texas eonstitutional

requirement of maintaining the integrity of

county lines whenever the United States

Constitution will permit iL, see Clements a.

Valles,620 S.W.zd 112, 113-15 (Tex.1981),

the drafters of the redistricting plans faced

the choice of dividing Dallas County into 16

slightly overpopulated districts or 17 slight-

ly underpopulated districts.5 The 1983

House plan ehooses the latter alternative,

as have all the plans presently before us.

The rate of growth in the county of the

anglo, black and hispanic populations was

not uniform. The minority populations in

4. The 1980 census sets the Texas population at

14,229,191. With 150 House districts, an ideally

apportioned district would contaiD 94,861 per-

5. Dividing the county inlo 16 districts would

result in districts containing approximately 97,-

284 persons. Dividing the county into 17 dis-

tricts u'ould result in districts containing ap-

proximately 91,561 persons. Although a deci'

sion to apportion all of Dallas County into l6 or

17 districts necessarily creates districts varying

2.@ to 3.50,6 from the ideal, the Texas Supreme

Court explicitly disapproved a split of Dallas

Countl'and seven other counties in the original

legislative plan, Tex.Civ.Stat.Ann. art. l95a-7,

because "[the State] failed to prove that thc

retcntion of surplus populations within the

boundaries oi thc eight counlies would resull in

impermissiblc deviations." Clements v. Valles,

620 S.\\'.2c1 et i I 5.

58I FEDERALSUPPLEMENT

iit ';

-

a

Dallas County grew more rapidly than the

anglo population. Thus, in 1970, the:black

population of 220,357 comprised 76.6% of.

the county population. By 1980, the black

population had increased by 30.5% +e 287,-

541, and comprised 18.5% of. the eounty

population. In 1970, the hispanic popula-

tion of 88,652 comprised 6.7% of the county

population. By 1980, the hispanic popula-

tion had increased by 74.3% to 154,560, and

comprised 9.9%, of the county population.

Parenthetically, we note that the census

method of identifying hispanics changed

between the 1970 and 1980 censuses, so

that the numbers given for 1970 and 1980

are not entirely comparable. See II Trial

Transcript 414-15 (testimony of Dudley Po-

ston).

Theoretically, the 1980 combined minori-

ty population would suffice to form almost

five House districts. The black population

alone could fill out slightly more than three

districts. The hispanic population, on the

other hand, could fill out slightly more than

one and one half districts.6 Naturally,

these calculations take no account of the

geographic distribution of the minority pop,

ulation in the county.

The minority population, for the most

part, forms communities in the central and

southern portions of the City of Dallas.

Approximately 48,000 blacks and hispanics,

however, live scattered throughout the pre-

dominately anglo communities in north Dal-

6. The exact number of districts to which the

minority population would be entitled under

this strictly proportional analysis depends on

the method of calculation. The black popula-

tion could fill out 3.03 "ideal" districts while the

hispanic population could fill out 1.62 "ideal"

districts. IV Trial Transcript 1090 (testimony of

Paul Ragsdale). Assuming that these figures do

not double count persons u'ho checked both

black and hispanic on the census form, the

combined minority population could fill out

4.66 "ideal" districts. In a l7-digrict apportion-

menl of Dallas Countl, the black population

could fill out 3.14 districts while the hispanic

population could fill out 1.68 districts. Again,

assuming no double count, the combined mi-

nority population could fill our 4.82 districts. /d

at l09l (lestimony of Paul Ragsdale).

las

p8l

rut

thr

sor

l

tior

the

acc

M/

ide

7.

lr

1,

o

3.

ir

rl

n

t)

r

h

d

p

p,

ir

r(

u

a'

n

ti

h

h

ci

d

1r

n

c(

rI

ir

n

- .Jr*l.-

t

t

.finnlzls v; CLEMENTS

Clte s 3El F.SupP. 1329 (t9&{)

r335

las county.? otherxiSe, the black and his- hood, known as "Little,,Mexico" consists of

panicpopulationsaremingledipanareaanareaslightly'northwestofdowntown

running along the line oi tfr" 1.rlnity Rir"r, Dallas and southeast- of love Field'ro A

through downtown Dallas and intp ttre second neighborhood, called "New Little /

southern part of th" c;;; ;;11"..;- Mexico" lies immediatelv northeast of

Although the brack and hispanic popula- il:Hf,H'iki.X?',T,Jffi""'frt":: ;t#:

tions live in close proximity to each other, as "El Poso," is located in the vicinity of

the hispanic population in Dallas County, downtown Dallas.t2 Three additional

according to testimony adduced by the neighborhoods, called "Los Altos l'a Va-

MALDEF Intervenors, has formed Several jate," "[,os santos" and the "L,edbetter"

identifiable neighborhoods.e One neighbor- area are located in west Dallas'r3 In addi-

7. Thus in the 1983 House plan, the six districts acknowledge may exist, result from shortcom-

thar run along the norlhernmost part of Dallas ings in May's testimony'

County have the following minority popula-

tions: 10. &e VI Trial Transcript 92 (testimony of Joe

Disrrict 98: 8,342 May)' May described the area as encompassing

District 99: 8,062 parts of voting precincts 3303' 3304 and 3386'

Disrricr l0l: 13,047 From the Dallas demographic map, this section

District ll2: 4,313 of the county varies from 2Oo/o lo 8Oo/o hispanic,

District 113: 6,079 and the northwestern portion of the area has a

Districr 114: 8,467 mixed population of 20o/o to 40%o black. From

l9g3 Joint Exh. 5. Aside from isolated pockets the statistical breakdowns of the plans, the cen-

of 50oo persons in northeast Dallas Countl' and sus tracts in the area May has described have an

3500 persons in north Dallas Counly, the minor- hispanic population of about 4200. See 1983

ity population in north Dallas County is dis' Joint Exh. 5 (census tracts 4 01, 5, 18 & l9).

persed.

8. Nearly 350,ooo blacks and hispanics reside- in tt. see VI Trial Transcript 87-88' May stated

the seven districts or th. issi iouse plan thar thar the area consists of voting precincts 3312,

run through central and sourhern Dalias coun- 1213, along wirh parts of voting precincts 3301,

ty. In rhise districrs, there are the following 2254 and 33O7. &e 1983 P-l Exh' 10' The

ririnority populations: Dallas demographic map indicates that this arca

District 100: 71,568 is from 200lo to 600/o hispanic' The 1983-House

District 103: 51,078 Plan statistical breakdown suggests that the area

District lO4: 8,750 tontains approximately 14'000 hispanics' See

District 107: 50,150 1983 Joint Exh' 5 (census tracts 8' 9' l0' 12' 15

Disrrict 108: 29,448 01' 15 02 & 24)'

District I l0: 66,382

District lll: 70,163 12' See VI Trial Transcripl 90-91 (testimonl'of

1983 Joint Exh. 5. Joe May)' May offered no voting precinct num-

9. The testimony concerning hispanic neighbor- bers foi the "EI Poso" community' The map of

hoods came principally from Joe Ma1', u'ho voting precincts with 40o/o or more hispanic

drafted MALDEF's most recent alternati'e population' 1983 P-I Exh' 10' shou's no hispanic

plan-the 'MAY-MALDEF" plan. For.lhe. most voiing precinct in the area May described' We

part, May described the hispinic n-eighborhoods decline to speculate about the size and exact

imprecisely. where he gave specific geog-raphic location of the "El Poso" community'

refirents for the neighborhoods, the referents

usualll'consistofvotingprecinctnumbers.Inls'SeeVITrialTrarrscriptg2-93'Thethree

at leasl one instance, the area described does ncighborhoods' according to May' consist of

nothaveahear,yhispanicpopulationconcentra.votingprecincts44l.land3353.Precinct3353'

tion.Byreferringtoprecinctnunrbers,MalaccordingtoMay'formsthcdividinglinebe-

has madc it difficult not'onl1'to gauge the exait tween the Los Santos and the Los Altos [:

irirp"ri. p"p"fation of th.i" u.iu.l u,hich ue Vajate comnfunities' We note that high hispan-

can derive only from the census iract break' ic-population voting-precincts lie adjacent to

dou'n in the district statistical summaries, e'g', 3353' We assume for present purposes- that

1983 Joint Exh. 5, bui also to correlate theic thcse precincts are part of the same neighbor-

n.igyborhu.ra, u'iih the black population con- hoc'ds' If so' according to the Dallas demo'

cenlration, *.hich u,e could harle icrived fron, graphrc map, lhe Ledbetter area has over 800/o

in. Outtur'a".ographic map. Anl,imprccisiotrs lrispanic p.pulation, and the other tu'o commu'

in tlrc descriptions in this opinion' of thcs, rrrtics havc from 2oo/o to 80% hispanic popula'

r.rr-rghboriro.ds, imprecisions uihich rvc rcaciilr ''tr r'ith a mixed black population of from 209'i'

58I FEDERAL SUPPLEMET{T

a

r336

tion, the area around Iove Field has a

substantial hispanic population.tt

Although these neighborhoods mav bepredominantly and idlntifiably hi.p"r;,

they.form separate enclaves l,f frirp"r"

population rather than one contiguou. t ir-

panic community. In most instinces, the

hispanie neighborhoods abut

".;;. ;;;;populations are a mixture of black and

hispanic, predominately black o, f"ig"iy

"r_glo. Generally, black areas are weiged

between the three hispanic neighborho-ods

north of downtown Dallas_Little Mexico,

New Little Mexico and the

"ru"

n""i fou-"

Field-and the three neighborhood. in *".i

Dallas-l,edbetter, Los Santos una f,o. et-

tos La Vajate. Moreover, the three hispan-ic neighborhoods within west Daflas,'ls

,?

?OY . .According ro rhe LRB House plan

statistical breakdown, the Ledbetter ur., t

"!-u.,nrspantc popularion of slightll. over 5600, see

1983 Joinr Exh. 5 (census tract 106), and the

31her

rwg.communiries, combined, ;pp;;r-i;

lur"-^1n- hispanic popularion of aboui 16,600.&e 1963-Jo_inr Exh. 5 (census tracts 2O, 42, 43,47,48,50.51, 52 & lor).

14. -About

350O hispanics live in the Love Fieldarea. &e 1983 Joinr Exh. 5 (census t.".r + 01.

15., With one exception, rhe neighborhoods ex.clustvel), abut other non.hispanic areas. Fol.

low-ing is a list of the census tracts thar adjoin

each neighborhood wirh tt. p..".","g" oi,i"predominate population group in

"uj ..nru.

1rac1. T_he figures are derived- f."- f"ini-ixh.5, For lhe purpos€s of illustration, *. hur. ,."Jthe term "anglo', as a substitute fo. the exhiiir

category "other," u,hich includes all those u,ho

are neither black nor hispanic. We include rhis

breakclown with the caveal that an] impreci.

sions in, rhe descriprions of rhe tirpr.il ,i"ign.borhoods and the surrounding aieas deriies

from the vagueness of the testim.-ony.or.".ning

the locations of rhe hispanic ,.ighlorlooai.---'

LITILE MEXICO [includes census tracrs 4 Ot,

5, I8 and t9l: rracts 4 03 (Love piefal

tO-O Zirz,

hispanic); 4 02 (st.7@A angto); 6 oi isi.l8v,anglo); 6 Ot (94.45or'u anglo); 7 Ot ia,.ei";,anglo); 17 o2 (92.62o7o black); 2r iSe.i8,r,a1g1o); and t00 (62.a6olo blacki.

NEW LITILE MEXICO [includes census

lra:ts..8, 9, tO, 12, l5 01, l5 O2, and 2al: rracri

l- (split tract) (9020 1 anglo); I $q9q%-i"

clo); 7 0l (62.660/0 anslol; 7 oz izs.as.r, u;

8lo); I I Ol (70.37oh anglo); l3 Ol (69.6404

anglo); t3 02 (tt)!oa anglo); u ioZ.tqbanglo); t6 (ez.s8o/o btack)J 2z or iii.is",.anslo); 22 02 (62.3so/o black); 23 iAO.iiiblack); 2-s (87.23o/o black); 26 iSz.iO"z.'Li".tll

well as the three to the north of dgwntown

Dallas, are not all contiguous to ure anoth-

I er. For example, the Iedbettei area is

isolated from the other two west Dallas

neighborhoods; it adjoins a black area with

less than 40% hispanic population on the

east, anglo areas with less than 40% his-

panic population on the south and north-

west, a black area on the northeast, and an

anglo area on the west. As the county

demographic map illustrates, the hispanic

population eonsists of six scattered areas

rather than a cohesive whole.rs lgg3 p_I

Exh. l0A. Indeed, the hispanic neighbor_

hoods are sufficiently dispersed such"that a

serious question exists whether any single

district could completely encompar. th"rnr.,.

81_(9O.33Vo anglo); and 122 03 (split tract)

(650lo + anglo).

LOS ALTOS LA VAJATE AND LOS SANTOS

[includes census rracts 20, 42, 43,i7, A,'sq

51, 52, and t0ll: rracrs ZZ OZ QO.Sloi ^rrli'.

.41

(94.95o/o black); 44 (66.33% ungtol;''ni

(64.13Vo anglo); 46 (64.480/0

^"Ad;' ;;(95.060lo black); Sf foe.SO"z anEioj; ;;

(7.s.l7oh black); 62 (47.16oh

^"gt"l ii.ei"t"

black); 63 02 (84.04oh anglo); i'00 G;.4;%black); 102 (89.o8o/o black)I ana rc4i;o.;;;;"

black).

LEDBETTER Iincludes census rracr l06l:tracts 100 (62.46o,b black); 105 (solir r.,.ir

(60e^o-1 black); 107 (69.6904 ungfoi re3-gj

\72.13_v: ansl o) ; I 5 I (90. t 3o/o angio; ;'

"nJ

r i i(87.75o/o anglo).

LOVE FIELD [includes census tracr 4 03]:tracrs 4 0l (wesrern edge of Lirrle Mexico)

\5_6.J6o/o hispanic); q -OZ (Sl.lOu" ini;,

2_2.08q0 black); 6 Ol (56.820/0 ungto); ii'O"j

\7l9lY: black); 72 (67.460/o

^"4";;' ;; o;(_88.21% anglo); 98 02 (66.t1o/o lriili, -"rj

l0O (62.460lo black).

15. One could debare whether the MAy_MAL-

D!f, ylal acrually encompasses

"f

f tf,. f,irf"ni.

neighborhoods in its hispanic aisrrict, ai'si.icil13.

.The.answer dependi on how.r;;Ji;;:"nerghborhood," and we have heard no testimo.nl on this definitional question. W. nor., ho.^l-

ever, thar the MAY_MALDEF plan splits uo six.

1::-...:ntr. rracrs jusl in drau,ing its hispanicolstrtct. In most instances it attemprs to eitract

the "most hispanic,, block groupe fi.-if,.-.pfii

census tracts. Whether or nol the plan succeedsin presening all the neighborto"a, *f,ii. .rt-

:llfl-ur. meandering path rhrough the ciry ofualas ts not, in our r.ieu., crucial. We areforced to wonder just hou. much these arcastrut-\' constitute .,neighborhoods,,,

as Ma\. tesri-tied, much less one cohesir.c,,communitr.,,,

u,hen a plan musr dra* such fi"" l;;"-;'b;i;;l

i/

I

I

i

(

1

I

t

(

1

(

!

(

r

I

e

o

I

'd

tr

tl

l

\

a

a

a

b

Jt

, .TERRAZAS v.. cLEMENTS

Clre u 5Et F'SuPP. t329 (19&l)

0

l--

B. The Districting'Plans.'

Partially as a consequence ofrdispersed

nature of the hispanic populations, Dallas

has never had an hispanic-dominated House

district. With one exception, the proposed

plans do not draw a district with an hispan-

ic majority. One plan-the "MAY-MAL

DEF" plan-creates a district with only a

bare hispanic population majority. The

voting age population for that district, how-

ever, is only 43.66% hispanic. While the

other plans that we have reviewed have in

common their lack of a hispanic district, the

plans differ substantially in their demo-

graphic and political consequences.

1. The Preuious Plan.

Before the 1980 census was taken, Dallas

County was divided into 18 single-member

House districts. The Texas Legislature

had drawn the districts pursuant to the

order of the United States District Court

for the Western District of Texas after

that court struck down a multi-member dis-

trict plan for the county in 1971. See

Gran:es u. Barnes, 343 F.Supp' 704 (W.D'

Tex.19?2), affd in part and rer"d in part

sub nom. White u. Regester, 412 U'S. ?55,

93 S.Ct. 2332, 37 L.Ed.zd 314 (1973). The

Graoes plan had divided the predominately

minority areas in and around the City of

Dallas into six districts: 33C, 33F, 33G'

33K, 33N and 33O.

These six districts were heavily populat-

ed with minorities. District 33C consisted

of portions of the black population in west

Dallas and included the hispanic population

around l,ove Field. District 33F, which lay

to the south of District 33C, took in most of

the area where, according to the MALDEF

Intervenor's testimony, the "Los Altos La

Vajate" and "[,os Santos" neighborhoods

are located, together with adjacent black

and anglo areas. Three districts, 33G' 33N

and 33O, ran through the predominatelv

black areas of south Dallas. Sec 1983

Joint Exh. 2.

dcrcrmining if a particular group of hispanics

living in roughlv thc samc area is indecd a part

The Graaes plan con(ained four districts

with substantial hispanic populations.

These districts varied }rom one with 19.8%

hispanic population to one with 31.3% his- /

panic population. A more completc break'

down of the minority populations in these

districts appears in Table A.

TABLE A

Minority Population In Graves Plan House Districts

(In Percentages)

Black Hispanic

Population Population

58.8 20.6

2,2 81.3

5?.9 8.0

3r.7 n.t

85.4 2.4

63.0 19.8

a. Black plus hirpanic adjusted to corr€ct double count

for those who checked both.

(Sourte: 1983 Joint Exh. 2)

In 1980, these district configurations had

resulted in the election of three black Rep-

resentatives. Representative Sam Hudson

was the incumbent elected from district

33C in west Dallas. II Trial Transcript

465-66 (testimonv of George Dillman); II

Trial Transcript 539 (testimony of Lee

Jackson). Representative Paul Ragsdale

was the incumbent elected from district

33N in south Dallas. II Trial Transcript

539 (testimony of Lee Jackson); IV Trial

Transcript 1082 (testimony of Paul Rags-

dale). Representative Lanelle Cofer was

the incumbent from district 33O in south

Dallas. /d. While the Grares plan was in

force, one other district, district 33G in

u'est Dallas, had, on t*'o occasions, elected

a black Representative. II Trial Transcript

539.

2. Thc 198J Hou.se Plan.

Despite the grovvth

tion in Dallas CountY

census revealed that

City of Dallf,s were

populated. Together,

tricts in central Dallas listed in Table A,

supra, were approximately 160,000 persons

of the ncighborhood.

District

Number

8:!C

88F

88G

88K

83N

slo

L

{337

MinoritY r

Population

7it.9

58.s

65.9

58.8

8?.8

82.8

of minoritv popula-

generally, the 1980

the districts in the

substantially under-

the six minority dis-

r338 58T FEDERAL SUPPLEMENT

TABLE B

ehort of the population necessarr for*six distrigt BBF; the district also extends for-"ideal" districts. District $C ;r;; f"ii ther west,

"rJ i..iri". sma, porrions of

$:f,"'#"J,::"';i'*ff"3"t:r:lYi* former diltric; iic""a 33o on trre eouth

urately blz st ort of an '.ideal,, district. IV and east' .See 1983 Joint Exh. z; rsai p-i

Trial Jtanseript 1089 fte.ti*ory or"p"rr Exh. 4. District l0?, in t"rg. ,""rureRagsdale). ' ----J

includes former district BBK togethe"

'riti.,

Ih:.19?3 House plan, Iike aI of the plans

a portion of former district iac. 198,

submitted to this 6o"t,

""a""r" the minori-

Joint Exh. 2; lgg3 p_I Exh. n. nist"iciiii

tydominated areas in central and southern includes most of former district $N, ;;

Dallas county into five districts.--;;: extends further south. l98B Joint B*r,. z;

sence, the 1983 House plan dismantlJ; 1983 P-I Exh. 4. District rrr in.ludesof the Graaes districts in tfre CIW oiD"il most of former distriet BBG, part of fo".".to build up the minority popuration il;j;: district BBo, and an area to the west ofcent districts' District ttio-

"r"orp"s.'*

Dallas that had not formerly been a p* ;imost of the population of former dil"i;; I: .?*"r city disbicr 19$ J. Exh. 2;3BC in west Dalras and extends ,";;;;;; 198s p_r E*h: a; breakdown of theinto predominatelv blaek."."u. th"irr"*l.- minority poprl"tion and voting age popula_Iy comprised a paut of district aso. sr;ll tion appea"s r", ""J'"r the five minorityTrial Transcript 856 (tesrimony oi L; districG ,ra"r-ir,"-igs3 House pran in Ta-Jaekson); r98B Joint Exh. 2; rgsi p-i EJi bre B arong *ir['ii,."r"re information for4. District 108 consists in part

"f f;;;; the three MALDEF plans.

District

100

108

l07

u0

1u

Minority r

Pop.

75.47

67.06

50.76

70.09

70.65

Minority e

VAP

n.77

47.52

47.78

68.44

@.ai

@.2,

56.65

53.63

6'/.&1

62.65

Likr

plan d

panie

contai:

Distrit

co" arr

panic

;

total r

which

most o

Vajate

an hisl

of the

these d

lations

neither

bined I

upamr

The <

tricts, I

election

tives.

merly <

district

dale, fo

tion in

incumh

run, a I

was elei

3. T)

The Il

three pi

.,MALD

DEF pla

to creat

Each pla

of minor

City of

each pla

politicall

IandM

con&rin a

conpariron of Brack, Hispanic and Minority composition of selectedDallas Crcuty Dstricts under l&3 House plan

LF.GEND: pop. = poprr"tiol

MALDEF Plans (in pertentages)

I.

VAp = Votlng Age population

lB3 House plsn

Black

PJ:] Hispanic HispanicroP' VAP pop vAp

II. UALDEF I House plsn

y 63.68 58.{i} a.fi

$ D,.67 mB 42.iy 8?.4s 3{.31 z,37

llg 71.47 6s.1e 3.nlll 61.15 u.74 9.8s

III. UALDEF. II House plan

100 6639 59.44lG n.u a.g6lfi i6A %i.atlr0 65.68 62.58ll1 65.?8 6r.?3

65a8 61.86

m.n 18.63

26.65 24.75

@.90 65.41

66.73 60.9r

12.49

85.54

29.01

3.57

10.10

10.39 9.6{

40.30 34.51

4.75 m32

4.69 {.03

5.18 1.43

11.06 ?8.ts

28.98 56.G

23.81 55.&'g.%, ?8.18

8.56 ?5.50

10.98 75.U

36.50 64.98

19.46 fi.47

zu 74.6

8.O7 ?0.68

68.88

59.29

43.50

6.42

65.96

T

iJ. --:-

tL.

. TERRAZAS.v. CL-EMENTS

' ClteuSEt F.SuPP. t321' (t9t4)

F

F

)

T

t

t

I

D

!

i.

!

r

r

;

L

b

I

F

I

t

110

111

118

III. UAY-UALDEF Hotrse Plcn

l1p

*8159 ) 16.61

tG 60.08 I 6.17

b {8.20 b

b ?52sc

b 74.53 c

b ?1.17 c

43.66 65.61 c

gether with a combined black and hispanic

f,opulation majority. In the MAY-MAL

bEF plrn, the hispanic district has a bare

hispanic population majority together with

a combined black and hispanic population

majority.

Although each of these plans achieves, at

least in theory, an hispanic-dominated dis-

trict by slightly different means, the line-

drawing in each plan dealt with similar

obstacles. The most serious problem, of

course, arises because only twelve of the

census tracts in Dallas County (143 04, 4

03, 30, 31 02, 33, 106, 4 01, 8, 10, 19, 24' 47)

contain more than 50?i hispanic population'

1983 Joint Exh. 5. Even these twelve cen-

sus tracts, which cumulatively contain

slightly more than 21,000 hispanics, cannot

alibe placed in a single contiguous district'

Only one plan-the MAY-MALDEF plan-

includes the four largest of these twelve

trac[s in one district, and even that plan

splits two of these tracts.

Still another problem arises from the

first. The MALDEF plans all attempt to

unite in one district at least part of census

tract 106, an 85'06'zl hispanic area contain-

ing about 5600 hispanics, and census tract

a 1g, a 6o.2lrt hispanic area containing

about 3300 hispanics. 1983 Joint Exh' 5'

To accomplish this union, the district must

traverse an area that forms a part of 1983

House district 100, and that formerly was a

part of district 33C from the Graues plan'

Although rthe area--census tract 100-it-

self contains a black population of onll

1446 persons, the area either adjoins or

gives access to other areas (census tracts 6

Ot. ff OZ, 102 and split tract 10ir) that have

adriitional black populations totaling ap-

lrroxittiltelv 11,200 llersc'ns' No district co-

rri'i; rrratic,rl for a irlr,r'I tiistlict that exclud-

(-\i ('('trstls tract l(-'(l i"uiri join these other

8?3E b 7.15

dt.?g r 8.88

11.18 1429 51.13

a tinority equala black plur hirpanic, edjuetcd for thooe who checked both'

b. lte MALDEF Intervenon hgve not supplied this infotmation'

c Total not adjugt€d for thooe who checked both blE k and hispanic'

(Source: 1983 Joint Exh. 2; 1988 P-I Exhs' 8A' S7')

Like the Graues Plan, the 1983 House

plan does not unite the six pockets of his-

panic population. Two separate districts

contain substantial hispanic populations'

District 107-which contains "Little Mexi-

co" and "New Little Mexico"-has an his-

panic population comprising 29'01% of the

Ltat aistti.t population. District 103-

which contains the Ledbetter area, and

most of the population in the Los Altos La

Vajate and l,os Santos neighborhoodt-}1?

an hispanic population comprising 35'54'i

of theiotal ditt.i.t population' In both of

these districts, the black and hispanic popu-

lations eombine to form a majority' In

neither district, however, does the com-

bined black and hispanic population make

up a majority of the voting age population'

The configuration of the 1983 House dis-

tricts, like Lhe Graaes plan, resulted in the

election in 1982 of three black Representa-

tives. Representative Sam Hudson, for-

merly of district 33C, won re-election in

district 100. Representative Paul Rags-

dale, formerly of district 33N, won re-elec-

tion in district 110. Although the black

incumbent from former district 33O did not

run, a black Representative, Jesse Oliver'

was elected from district 111'

3. The MALDEF Plans'

The MALDEF Intervenors have offered

three plans-the "MALDEF I Plan," the

"MALbEF Il plan" and the "MAY-MAL

DEF plan"-that have a common objective:

to create an hispanicdominated district'

Each plan creates five districts in the areas

of minority concentration in and around the

City of Dallas. In one of the districts in

each plan, hispanics would potentiallv be a

politically decisive force. In the MALI)EF

i and MALDEF II plans, the kev districts

contain an hispanic population pluralitv to'

1340 58I FEDERAL.SUPPL'EMENT ?

areas with the rest of district lOit. Inshort, the line draw

make a .h"i;; ;;;;::: xffiJt",l,.T *hispanie populations.

-

Finally, the MALDEF plans all excludethe same predominately anglo ;;';.;;their hispanic-dominated O[tri.t".--f"rii_

mony adduced by the MALDEF Ir;;;_nors suggested that these affluent angloneighborhoods, which are a part of one of

llr" y^":l strongly hispanic di.tri.t una".the 1983 House plan, h"d ;-;;;;;;;

::::lC propensity to oppose ,ino"ity

""nJio,"*aj I'hese areas, referred to as ,.Kes_

sler. Park" and ,,Stevens park,,,

"Jirm-ii*predominately hispanic areas in west Dal-las. VI Trial Transcript 99, 102_08 (te;;-

mony of Joe Mry); il. aL 66,78 (testimonv

of Trinidad Garza,l.rt The three iliD;i

plans cut a careful line around these anglo

neighborhoods and move th", ir;;;;;;:

dominately black district to the south.

.

The three plans also have in commontheir effect on the hispanic ;"r;;;l;;.rike the 1983 House plan, the'Md#;

plans place parls of each of th" .ir.;;;;of hispanic population into at [r:.;-;;;

separate districts. The three ptans aiifer

fll:flr,. in their.respective perceno*".'ri

nrspanrc population in the hispanic_do-mina t_ed districts and their effeci on ;l;;;;;

black districts. The MAy_Meiorili",

is- unique in that it embraces

"t_Iea-;r, ;;;of the identifiable hispanic communltiel innorth Dallas and west Dallas. il;;;;

achieves an hispanic population ,"io"ii.,,

gnlv b-v creating a alstiici ,f,", .rn.-'rf,."'"

tcntacle-like corridors through ,""rt

"njcentral Dallas. A more complete break-

9:*l of the minority populations in ea.f,qrsulct appears in Table B.

IiI. THE PARTIES' CONTENTIONS.

^

The MALDEF Intervenors urge thisCourt to strike down the Dallas er;;;districts in the lgg3 House plan b;;;:

they violate section 2 of the V",irg nigii.

1_.j ?, dituting hispanic votinf .i.-".,";;;and because the plan,s drafters .oni."_

,r......t^r:n, the, descriprion of the neighborhood,wc as(Uill(.that the u.itnr

t r,. i,,, .',.,,-,"' ."IJi'j'iii:,1'::il:J;l,.j;tJ:

vened the constitution by purposefulty creatlng that ditution. ff,"

"""fjgr*iffir";;the districts, in the MALDEF;;;;;;

estimation, combine with politicai ;;il-tions in Dallas County to ensure ,hJ;;

h.ispanic population

"rjoy. 1"., oppoJuiti

than others to elect-.iraia"t"r'J-ii,"ir"

choice..

.Purportedly, the State dla;;#;

llll y,,h,the transparent intent to protect

tneumbents by harming Dallas hispanics.

The Dallas districts, the MALDEF Inter-venors maintain, fragment a cohesive his_panre community. The plan allegedly joins

hispanic neighborhoods to politicilty ilJ;anglo neighborhoods with the

";r;i;-;h";the,largest groups of f,i.puni. ,-ot

^"n*rrauas Uounty are rendered politicallv im_potent. As the MALDEF lnL*"no.. .""the matter, its alternative plans

""A1"."the ease with which the distiictinC ;;;;;i

!y *.uld. have designed at least or'" air-t-"i.tln whreh hispanics could have turned anundesired ineumbent out of offi." anA ir-stalled a eandidate of their choice.

The MALDEF Intervenors assert thatthe failure to draw such a di.t"i"t ;;.;';;

regarded as discriminatory. past potiticai

discimination and the lingering

"fi".t_ "igeneral discrimination againsi trispanics

have al legedly rendered tf,", pollti..it,'i"_

active. Aeeording to the MALDEF. irt""-venors, political polarization, evidenced U,

otoc voting, leads to a predicLable result forhispanics-virtual disenfr"n.f,i."r"rt.

-

.i.one consequence, the MALDEF, Interve.

loT polt out, no hispanic has ever ."*"a

fl ,h"-'I'exas [,egislature as a Representa-

tive of Dallas County.

.

The State, in the MALDEF Intervenors,

vrew, can muster no policy adequate tojustify the impact of tlie tS8B i"ir.""pf#

on hispanics. The sole lustlfication of iheplan- allegedly derives fro, incumb"n.r.

While the MALDEF Intervenois'co;;;J

that the State Defendants may legitimatelv

consider the political effeets of

"""af.i."i-

in$, the Ig8g House plan purportedlv

aehieves its political ends Uy fi;;;;ili;

hispanic neighborhoods identified as Los Alrosl-a Vajate and Los Sanros.

gerr

tion

N

MA]

the

gTAI

tion.

dict*

ttcra

is cr

the I

ofD

astr

lya

gem(

that

the 1

Defe

conti

the r

Ac

distri

ble <

neigt

hoodr

nine

ed, w

In th

DEF

dence

ryma:

asser

plain

hispar

er nal

Mor

view

failed

ty ele

panics

fendar

olithic

tion g

status

facto

does r

assert

ness d

ic canr

Finr,

uit ' :

Ee-

tof

,rs'

rdi-

tlre

riB

Eir

the

nct

ics.

tpnnez.l,s v. GIJMENTS l34t

Cltc.r Stt F.SuPP' 132'!l (l9A{)

gerrymandering a nitural hispanic popula- tion of State policy'

"

Incumbency' accord-

tionconcentration'Iinctoth.estateD.efendants,providesonly

Naturally, the Stat€ Defendants deny the a lart of the plan's'rationale' The State's

MALDEF Intervenors' "tai"cte'ization

of po"rio Ato allegedly.advances related int'er/

tireplan,sdesignandresult.Thegeo.ests_continuitywiththepreviousdistrict.

graphic dispersion oi ii,"-t'i'p'nic popula- ing flan' and the preservation of Repre-

'

tion, the state Defendants contend, contra- .Jnt tir.-.onstituent relationships' In ad-

dicts any notion that the plan fragments- or dition, the state Defendants point out that

,,cracks,, any community of hispanics that the drafters had to consider the effect of

is cohesive. FurttrermJre,-in if," view of the plan on black voters' The State De-

the State Defendants, the political climate fendants allege that the MALDEF plans

of Dallasisnotsointo.fitif"tohispanics jeopardizeblackinterests; allof theMAL

,. t outig" the state to construct artificial- bn-r pt"nt pair an anglo incumbent against

ly a district that ensures loca) hispanic he- the most junior black Representative' 9n"

d".*r. ir,e state Defendants also argue of the plans' the MAY-MALDEF plan'

ii,"i tr.rl MALDEF Intervenors misconstrue eviscerates the district of yet another black

ii" pt"n,. purpose. The plan, as the State Representative. The State Defendants as-

o"t"na"nt. emphasize, aims at maintaining-

'"'i thut this court should defer to the

continuity and avoiding retrogression of legislative judgment about how best to re-

the voting strength of blacks' solve these conflicting interests fairly'

According to the state DefendanG' the Iv. THE APPLICABLE STANDARDS'

li:"::',1":?;;:'L"'*'.'':fi,J":T;::r,:l?; Since the supreme court rirst roraved

neighborhoods. The hispanic' neighbor- into the "political thicket" of reapportion-

hoods, which are separated by as much as ment in the 1960s' courts have struggled

nine miles, have allegedly been consolidat- with the task of developing manageable

ed,wherepossible,inareasonablemanner'standardstodeterminewhentheprocessof

ln the State Defend"nt uit*, the MAL line-drawing becomes invidiously discrimi-

DEF Intervenors cannot, under the evi- natory' On one hand' courts have not tol-

dence,arguethatthelg8SHouseplanger.eratedpoliticalsystemsthateffectivelyex-

rymanders.Rather,theStateDefendantscludeminorityvotersfromthedemocratic

assertthattheMALDEFlntervenorscom-processes'l':'^''!:'W'hitett'Regester'412

plainonlyoftheplan,sfai,luretomaximizeu.s.zss,?65-?0,93S.Ct.2332,2339-4|,37

hispanic voting ,*"ngih b., tarving up oth- L'Ed'zd 314 (19?3); ForLson t' Dorseg' 379

er natural popuiation patterns' U'S' 433' 439' 85 S'Ct' 498' 501' 13 L'Ed'zd

Moreover, the State Defendants take the 401 (1965) (dictum); Zimmer t McKeilhe n'

view that the MALDEF lntervenors have 485 F'zd 129?' 1304-0? (5th Cir'19711) (en

failed to demonstrate tt"t tt'" Dallas Coun- bat'tc)' offd on other grounds sub norrt'

ty electoral system

-i.

,igg"a against his- Easl cairoll Parislt school Board t'' MQr'

panics. Ti,e eviOenc", '"?lt

tf'" St"te De- shalt' 424 U'S' 636' 96 S'Ct' 1083' 4?

fendants,construction,establishesnomon-L.Ed.zd296(19?6).Yet,ontheotherhand.

olithic polarizatlon in oloting among popula- courts have consistently eschewed the no-

tion groups that mighi lra-n*ror* irispanic tion that the united States constitution

status as u poprt"tion 'i"ofii

i"" '' tt secures to any group of citizens the right

facto withdrawal of the right to vote. Nor to obtain trolitical representation in propor-

does the evidenee, if,. S"t. Defendants tion to its numbers ' E'g'' Whitcomb t"

assert, sho'*' hispanit-potitit"r powerless- Chattis' 403 U'S' 124'156-57' 91 S'Ct' 1858'

ness despite ttre frequent failure of hispan- 18?i-?6' 29 L'Ed'zd 363 (19?1)' In the

ic candidates at the polls. p)'f,st,nt case. \4'e are presented u'ith two

Finalh',theStateDefendantsdisagreevririalionso":hl:-:*:*"ofhou'todrawthe

u.irlr tlrv IlALDEF Inter'en.rs' interlrretlr- lr: :'t'trvt't'n securing the right t'o partici-

ter-

his-

0ns

tile

hat

in

lm-

lee

lee

)ri-

let

an

in-

|at

be

18I

of

k

ht-

lr-

by

DT

Is

e-

Dd

L.

a

bo

u:l

l€

v.

td

ly

t-

b

b'

r342

pate politically and avoiding government by

quota.

ll,2l Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Aet, 42 U.S.C.A. 5 lgTB, as amended in

1982, and the fourteenth amendment to the

United Stst€s Constitution offer related

remedies for minority groups that have

suffered interferenee with their right to

vote as a result of the voting practices or

procedures in their eleetoral system.tE To

obtain either remedy, a plaintiff must show

that, in the totality of circumstances, ,,the

political processes leading to nomination

and eleetion were not equally open to par-

ticipation by the group in question-that its

members had less opportunity than did oth-

er residents in the district to participate in

the political processes and to elect legisla-

tors of their choice." White v. Regester,

412 U.S. at 766, 93 S.Ct. at 2BB9; see 42

U.S.C.A. S 1973b. Under neither test does

the failure of a minority group to translate

its voting strength into proportional repre-

sentation suffice to establish a lack of ac-

cess. Whitcomb u. Chauis, 403 U.S. at

156-60, 9i S.Ct. at 187*77; 42 U.S.C.A.

1973b.

t3l Both the constitutional jurispru-

dence and section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act have employed a group of objeetive

evidentiary factors to measure the discrimi-

natory effect of a voting praetice or proce-

dure on minority voters. See White a.

Regester, 412 U.S. at ?6G{9, 98 S.Ct. at

233941; Zimmer o. McKeithen, 48b F.2d

at 1305-{6; S.Rep. No. 417,97th Cong.,2d

Sess. 28-29, reprinted in, tgSZ U.S.Code

Cong. & Ad.News 177, 20G{7 (report of

18. Some courts have identified two separate the-

ories under which a plaintiff might show rhat a

redistricting plan discriminates invidiously.

E.9., Zimmer t McKeithen, 485 F.2d ar 1304.

According to these cases, a plaintiff may shou,

either a "racially motivated gerrymander"-

Gonillion v. Lighr/oot, 364 U.S. 339, 8l S.Cr.

125, 5 L.Ed.2d ll0 (1960) is the paradigmatic

cas€-or an apportionment scheme that oper-

ales lo cancel out the voting strength of a mi-

noritl' group. E.9., White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

at?66-70,93 S.Cr. at 233941. The nvo lines of

cases were theoretically dislinct because the lat-

ter, or "dilution," line of cases did not, under

earlier interpretations, require a sho*,ing of in-

tent, *,hile a racial gerrymander did contem-

68I FEDERAL SUPPLEMENT

-. Committee on the Judiciary endoraing lgg2t

amendmer-'ts to the Voting nigl,t" e.ti

The factols include historical inqri"l".

"uii,as the effects of past discrimination, indicia

of race or ethnicronscious polities Buch as

polarized voting, and formal'obstacles to

minority success at the polls such as anti-

single shot voting requirements or majority

vote rules. The objective factors aid in

distinguishing mere political failure from

unlawful deprivation of political participa-

tion.

t4l Despite the common purpose and

evidentiary focus, section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act demands a less exaeting burden

of proof. To find that an electoral system

violates the constitution, a court must de.

termine that the discriminatory impact of

the system derived from the intent to bring

about that result. See Rogers a. Lodge,

458 U,S. 613,6t6-22,102 S.Ct. 3272,3275_

78,73 L.Ed.Zd 1012 (1982); City of Mobite

a. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 66-21, 100 S.Ct.

1490, 149${1, 64 L.Ed.zd 47 (1980)(plurali-

ty opinion of Stewart, J.\; accord id. at

99-101, 100 S.Ct. at 1516-151? (White, J.,

dissenting). The objective factors in White

and Zimmer may, but do not necessarily,

support an inference of intent. Compare

City of Mobile a. Bolden, 446 U.S. at 72-

74, 100 S.Ct. at 1502-1503 (plurality opinion

of Stewart, J.) (objective factors "far from

proof" of discriminatory purpose) with

Rogers a. Lodge,458 U.S. at 623-27, l0Z

S.Ct. at 3279-81 (finding evidence, based

principally on objeetive factors, sufficient

to support inference of discriminatory in-

plate a showing of intenr. See Zimmer v.

McKeithen,485 F.2d ar 1304.

We do not think that this distinction has

clearly survived later developments in the law.

Thus, some courts have treated what were es-

sentially racial gerrymander claims as voting

dilution cases. See e.g., Kirksey v. Board ol

Supervisors, 554 F.2d t39, t4243 (5th CiO (en

banc) (claim that single-member districr lines

fragmented cohesive black community), cert.

denied, 434 U.S. 968, 98 S.Ct. 512, 54 L.Ed.2d

454 (1977). Furthermore, a dilurion claim

brought under the constitution musl no\^. in-

clude proof of discriminatory intent. Rogers r,.

lndge, 458 U.S. 613, 6tGI9, 102 S.Cr 3272,

3275-77,73 L.Ed.2d l0l2 (l982)

tent). Ui

Rights Ac

lish a viol

tory rcsu)

through tl

. tors. Seo

No. 417 a,

Cong. & I

Althoug

vant to bo

ry inquiry

different

must discr

tors under

tests. Th

how the r

districts c

voting pra

A. The

tsl Bef

cases that

of voting ,

quired a s.

To harmor

with the st

protection

Arlington

ing Deuelt

s.ct. 555,

preme c/ou

19. Origina

a cause ol

ment. Se

(filed Jan.

fifteenth a

presently s

rality opin

amendmer

contempla

pose. 446

(opinion o

ion goes c

ment exler

from inter

and vote.

other Jusl

greed with

l0O S.Ct. a

id. at 102,

ing); id. a

shall, J., d

that the p:

ment remi

619 n.6, l(

nol arguecl

I

I

i

t

)

h

f.b

b

b

h

h

nr

>

s

t.

tent). Under section 2 of the Voting intent requirement into the voting dilution

Rights Act, howewr, a plaintiff can estab, line of cases for the Iirst time.m Section 2

lish a violation by showing thc diserimina- represents Congresl' judgment that focus-

tory result, whieh in turn can be proven ing on intent diverts attention from thd

through the aggregate of the objective fac- crucial issue-+quality of access. S.Rep.

tors. See 42 U.S.C.A. 5 19?3(b); S.Rep. No. 41? at 16, 1982 U.S.Code Cong. & Ad.

No. 417 at 2$-30 & n. 118, 1982 U.S.Code News at 193.

iIERAAZAS v. CLEMENIS

ctr6 u 3tt r.bupp. tizs (lrsa)

1343

Originally, section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act had merely tracked the wording of the

fifteenth amendment,zr and the Supreme

Court read its provisions as coextensive

with the constitution. Bolden,446 U.S. at

60-61, 100 S.Ct. at 1495-1496 (plurality

opinion of Stewart, J.). In June of 1982,

Congress amended the Act to prohibit elec-

toral systems that had invidious resulls

even though the systems might not clearly

have been installed in order to discriminate.

The Act presently reads:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequi-

site to voting, standard, practice, or pro-

cedure shall be imposed or applied by

any State or political subdivision in a

manner which results in a denial or

abridgment of the right of any citizen of

the United States to vote on account of

race or color, or in contravention of the

guarantees set forth in section

19?3b(fl(2) of this title [which applies the

Act's protection to members of any lan-

in this case lo impose a standard different or

more liberal than the fourteenth amendment or

the Voting Rights Act. The MALDEF Interve-

nors did not include the fifteenth amendment

claim in their statement of issues of fact and

law remaining in controversJ'. We do not there-

fore consider the scope of thc fifteenth amend'

ment separatel)'.

20. Lower courts, including the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit, had rcad Arlingtott Heights

and related cases as applying to voting dilution

claims. See Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.zd 2O9,217-

25 (5th Cir.l978).

21. When enacted on August 6, 1965, the statute

had read:

No voting'qualification or prerequisite to vot-

ing, or standard, practice or procedure shall

be imposed b1' an1'State or political subdivi-

sion to deny or abridge the right of any citi-

zen of thc united states to vote on accounl of

race or color.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, Title I, S 2,79

Stat.437.

I

I

I

I

I

r

?

Cong. & Ad.News at 20G{7 & n. 118.

Although the objective factors are rele-

vant to both the constitutional and statuto-

ry inquiry, each test relies upon them for

different inferences. Accordingly, we

must discuss the significance of these fac-

tors under the constitutional and statutory

tests. This discussion will also eonsider

how the configurations of single-member

districts can constitute a discriminatory

voting practice or procedure.

A. The Section 2 Test.

15] Before Bolden and the lower court

cases that anticipated its holding, the law

of voting dilution had never expressly re-

quired a showing of discriminatory intent.

To harmonize the law of voting dilution

with the standard prevailing in other equal

protection cases,le see generally Village of

Arlington Heights u. Metropolitan Hous-

ing Deuelopment Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 97

S.Ct. 555, 50 L.Ed.zd 450 (1977), the Su-

preme Court in Bolden explicitly read an

19. Originally, the MALDEF Intervenors pleaded

a cause of action under the fifteenth amend-

ment. See Complaint in Intervention at 14

(filed Jan. 4, 1982). The application of the

fifieenth amendmenl to voting dilution cases

presently stands in an uncertain state. The plu-

rality opinion in Bolden states that the fifteenth

amendmenl, like the fourteenlh amendment

contemplates a showing of discriminatory pur-

pose. 446 U.S. at 61-62, l0o S.Ct. at 1496-1497

(opinion of Stewart, J.). Ultimately, the opin-

ion goes on to state that the fifteenth amend-

ment extends only to protecting black citizens

from interference with their right lo register

and vote. ld. at 65,100 S.Ct. at 1498. The onll

other Justices who considered the issue disa-

greed with the plurality analysis. Id al 85-86,

l0O S.Ct. al l5O9-1510 (Stevens, J., concurring);

id. ar lO2, l0O S.Ct. at 1517 (White, J., dissent-

ing); rd at t25-35, 100 S.Ct. at l53l-36 (Mar-

shall, J., dissenting). Rogers v. Lodge suggests

rhat the precise scope of the fifteenth amend-

ment remains an open question. 458 U.S. at

519 n. 6, 102 S.Ct. ar 3276 n.6. The parties have

n(,t argued rhat lhe fifteenth amendment applies

1344 58I FEDERAL .SUPPLEMENT

grlg_" minority], as provided in subsec_

tion 0) of this section. ..

--""""

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of thissection is established if, based ;; d;totality of circumstanees, it is ,f,o*n tf,ri

the political processes f"uairg t"-norlni-

tion or eleetion in the StatJ r; ;;i;;l;;subdivision are not equally ,p;";';;;:

ticipation by memberJ of a ciass ,f ;iti

zens protected by subseetion (a) of this

section in that its members h;; [;;opportunity than other members

"f ;h;

electorate to participate i, tfr. prfltL"l

process and to elect representatives oitheir choice. The extent to which meml

bers of a protected class have b;;; ;i;;;

ed to office in the State or political subdi-

vision is one circumstan.u thut mrr,-;;

considered: proaided, fhat nottrins inthis section establishes a righl a; ;r;;

members of a protected clasls

"tuo"a

in

numbers equal to their proporti", i; d;population.

42 U.S.C.A. S 19Zg (West Supp.198B).

. The-Janguage of the Act, whieh derives

from

-Wh.ite

o. Regester,4lZ U.S.

"t

i66, 9;

U:,T.!" House report endorsed an earlicr vcrsionor lhc seclion 2 amendment, H.n.f f f Z, SZihCong., tst Sess., which h.a in.o.por"r.J'u',:*'

suhs" lesr wilhour rhc d"finiii",iri r.,"iilr'il,subsecrion (b) of thc final bill, ;"a'J,i.lrri'ri.

caveal aboul proportional r"pr.r.n,o,iun.-'ft"

rrnar language of thc bill resulted f.o. , .o.-promisc in the Senare Committee on rt. :Jili-

1_v. See S.Rep. No. 417 ar 3, 1982 t.aril;

!ong. & Ad.Nervs ar 180 (hisrory

"] ifr.; i,fil.Arguabl5,, the House Report is, u. u ,".rtr,-i"..a-uthoritalive on the meaning of the e.r.- i-rnthe Hcr-usr. floor debares f"ff"*i"g i"""," nlrls,age_.of tht' measurc, horvcver, ir app"ar.. fharthe House merelv vieu.ed ,r," ..rnpl"rnir" ir"-

Euagc as a clarificarion

"f rn" H,r,j."l o",-igii"iintenr. 128 Cong.Rec. H3gaa (dai11:

";. ;;:;;,t98l).

23. Thc dcvclopment of rhe constirutional iuris.prudcnce on voring dilurion h".

";; Ir;.:.:i;;;

lnstances in uhich courts have a.guabl1,r".:isJ

the meaning of earlier. cases. In the SuprcmeCnurr, for example, thc Bolden pi;;;lj,;;"b;;1:rj' announced thar ihc Wite r. Regcit", cas",which conlemporan. courts hud ,;,^"; ;.":resutts casc, required a shou,ing of discrinrin:r,torv inrcnr. See Bolden,416 U.S.

"r eS_20,"i00

?,S, ,i] ]tq?-,s01.

(pluralirr opirrion ot st"r,,r,iJ..1. r.\'cn lhc author of rhc t,purion in Wttitt rl.

R_egester apparcntl-r agr (.cd. 5", Orta"rr,"'lid

U.S. ar l0l-O3, rUi S ir. ar rstT_18 (\\.hirc, i.,

S.Ct. at 2889, air4s at codifying pregolden

case law. See H.R.Rep. N;.'zqt, iiti

Cong., lst Sess. 29-80 (Hous" Co.m;Iil;

on the Judiciary recommending ,,""suits'i

amendment to section Z of the V;ti""

IrF .!:t)t_,, s.Rep. No. tn it rti.

27-28, tgBZ U.S.Code Cong. & ea.N"ru.li

192-202, 20446. Congress viewed pre-

Bolden case law as evaluating tf," ai.cjmi

natory nature of the electoral .y.t". inquestion solely on the basis of oU:".li""

criteria.23 ld., l9g2 U.S.Code Cong. &-Al.

News at t96-202,20446. To

"id

;, ;p;i;

ing section 2, Congress enumerated typical

objective factors derived *o^ wilir'"ii

Zimmer:

1. the extent of any history of official

discrimination in the state or political

subdivision that touched tf,e rlghi oi il;

members of the minority grouf t"

"";;;_ter, to vote, or otherwise to p"rtl.ip"ti in

the democratic process;

2. the extent to which voting in the

elections of the state or politicalsubdivi-

sion is racially polarized;

dissenring). A panel of rhe Fifrh Circuil under-took a similar reinterprelalio n of Zf *rrrr- r,.M_cKeithen. See Neveir v. Sides, 571 F.2d at22U228. In both insrances, fellow ju;isi;;i;:

crzed^r'hal the1. perceivcd

". "" ir;";:i.,;";.rec botde,z, 446 U.S. ar 103_4t, tO0 S.Cr. ar

].5-ll-39 (Marshall, J., disscnling); U"u",i, Sii

I..-rO,

u, 23r-38 (Wisdom, :., .p""liollr .""*r-rlngr.

S

C

2

4

Z

C

m

Ultinratelv, thc rcasoning in l,lthite t. Regesterand Zintntcr t,. McKeitlu.n u,ill bear

"ith;;;;;-

1"11. *l1l presenl purpos.r, ho.r", "..'C;;;;;;nas. madc clear its undcrstanding rhrt , ."orriundcr seclion 2.should applt Wie

^"a