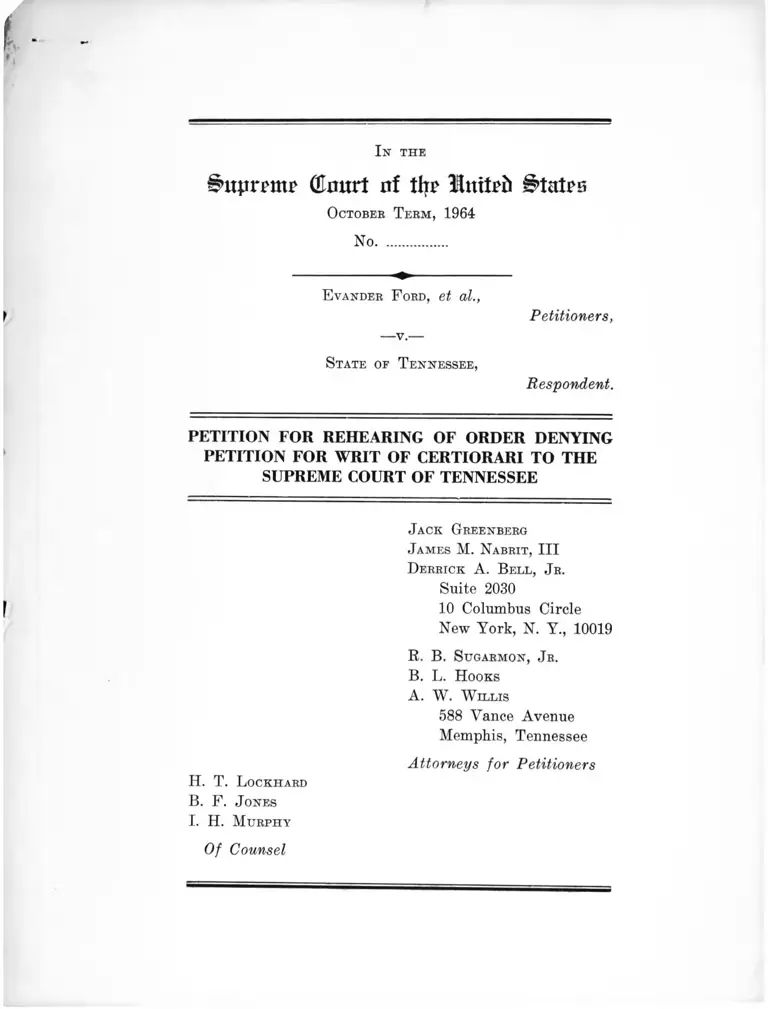

Ford v. Tennessee Petition for Rehearing of Order Denying Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Tennessee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. Tennessee Petition for Rehearing of Order Denying Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, 1964. 8048bc2d-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c7637aa-0de2-4b19-94ec-5e1d0f1075f5/ford-v-tennessee-petition-for-rehearing-of-order-denying-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-tennessee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(Emtrt nf tit? United States

October T erm, 1964

No.................

E vander F ord, et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

S tate of T ennessee,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR REHEARING OF ORDER DENYING

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE

H. T. Lockhard

B. F. J ones

I. H. Murphy

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

D errick A. B ell, J r.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y., 10019

R. B. S ugarmon, J r.

B. L. H ooks

A. W. W illis

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

Of Counsel

30580—2 Proofs—7-13-64

I n the

Supreme (dmtrt of % Itttl?b States

October T erm, 1964

No.................

E vander F ord, et al.,

—v.—

Petitioners,

S tate of Tennessee,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR REHEARING OF ORDER DENYING

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE

Petitioners, Evander Ford, Jr., Alford 0. Gross, James

Harrison Smith, Ernestine Hill, Johnnie May Rogers,

Charles Edward Patterson, Edgar Lee James and Katie

Jean Robertson, pray that this Court grant rehearing of

its Order of June 22, 1964, denying the Petition for Writ

of Certiorari, and that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Tennessee in the

above entitled case as prayed for in the Petition filed Sep

tember 1,1962, herein.

Negro petitioners were arrested in Memphis, Tennessee,

on August 30, 1960, at an open air auditorium located in

city-owned Overton Park which had been leased to a church

group for a segregated church meeting. They were con

victed on June 19 and 20th, 1961, of willfully disturbing

a religious worship (§39-1204, Tenn. Code Annot.) and

each was sentenced to 60 days in jail and fines of $175.00 to

$200.00. The Supreme Court of Tennessee affirmed the

convictions on March 7, 1962.

2

Reasons for Granting Rehearing, Issuing the Writ

or Granting Other Appropriate Relief

On May 27, 1963, this Court decided Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, holding that delay in desegregating

public recreational facilities in the City of Memphis could

not be justified under the Constitution. The original record

filed in that case contains facts, which by decisions of this

Court handed down subsequent to the trial of this cause,

are pertinent to, but not contained in, the records of the

petitioners’ convictions.

At the time of petitioners’ arrests, Overton Park was

designated by the City of Memphis for use by white per

sons only (Orig. R. 18, 24).* Negroes were excluded from

Overton Park, and if Negroes attempted to enter the Over-

ton Park or any other segregated park, they could be re

quested to leave by the Park Director, park employees, or

any member of the public (Orig. R. 26, 188) (T. R. 75-76).

Park personnel were informed as to which public parks

Negroes were permitted to use (Orig. R. 26). After Watson

v. City of Memphis was filed in May 1960 to desegregate

public recreational facilities in Memphis, the City deseg

regated some facilities previously limited to whites, includ

ing a zoo and art gallery located in Overton Park to which

Negroes were admitted in November 1960 (Orig. R. 167)

(T. R. 66). Generally, Negroes were not advised by the City

when parks and other recreational facilities were opened

to them (Orig. R. 186) (T. R. 76-77). They were expected

* Record references cited as (Orig. R.) are to the pages of the

original record in Watson v. City of Memphis, as prepared by the

district court and subsequently forwarded to the Court of Appeals

and to this Court. For convenience, pertinent excerpts of the

original record have been made an appendix to this petition.

References cited as (T. R.) are to sections of the Watson record

printed in the Transcript of Record for this Court (No. 424 Oct

Term, 1962).

3

to learn of changes in racial policy by usage (Orig. R. 187)

(T. R. 76). As one city official put it, Negroes were free

to use any park where police did not put them out (Orig.

R. 185) (T. R. 76-77).

Thus, it appears that at the time when petitioners were

arrested at Overton Park, it was segregated pursuant to

City policy.

On May 20, 1963, this Court in Peterson v. City of Green

ville, 373 U. S. 244, reversed trespass convictions of Negroes

who, after having been refused service at a lunch counter

because of race, remained seated over the manager’s pro

test. There, a city ordinance forbade nonsegregated food

service, but the State contended that the arrests were made

pursuant to the manager’s request and not the segregation

ordinance. The Court ruled however, that:

“When a State agency passes a law compelling per

sons to discriminate against other persons because of

race, and the State’s criminal processes are employed

in a way which enforces the discrimination mandated

by that law, such a palpable violation of the Four

teenth Amendment cannot be saved by attempting to

separate the mental urges of the discriminators.” 373

U. S., at 248. See also Lombard, v. Louisiana, 373 U. S.

267.

Similarly, in Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267, also

decided on May 20, 1963, the Court reversed trespass con

victions of Negroes who refused to leave a refreshment

counter in New Orleans after being advised by the manage

ment that the counter was operated on a segregated basis

and served only white patrons. Segregated facilities were

not dictated by any statute or ordinance in New Orleans,

but the Mayor and Superintendent of Police had issued

statements warning that persons participating in sit-in

4

demonstrations would be arrested. The Court ruled that

the convictions as in Peterson, supra, had been commanded

by the voice of the State and could not stand.

On June 22, 1964, this Court, in Robinson v. State of

Florida,----- U. S. ----- , reversed convictions of Negroes

and whites who were refused service at a Miami restaurant.

Again, relying on the rationale of Peterson, supra, and

Lombard, supra, the Court ruled that State health regula

tions requiring separate facilities for each race connoted

a State policy of segregation which placed discouraging

burdens on any restaurant serving the two races together.

Petitioners submit that this Court’s rulings in Peterson,

Lombard and Robinson, are applicable to the convictions

for which review is sought. As the Record in Watson v.

City of Memphis makes clear, segregation in Overton Park

was required by the City of Memphis. Legal action had

been initiated to desegregate all facilities such as Overton

Park and the City had begun a practice of desegregating

some parks, not by announcing that they were desegregated,

but by not arresting Negroes who attempted to use them.

Thus, petitioners’ arrests were not only mandated by

state policy as in Peterson, Lombard and Robinson, but

took place during a period when some Negroes, willing to

risk humiliation and possible arrest, were being permitted

to use some previously segregated park facilities. More

over, as set forth in the records of their convictions (R.

instant case, 78-79), their presence at the meeting was in

response to newspaper invitations not limited to whites.

Upon refusal to leave at the request of church officials

(R. 91), they were directed to seats in the rear of the

auditorium (R. 285, 293); and even after ignoring this

request and obtaining seats among the audience (R. 92),

the meeting continued until the police arrived, halted the

proceedings and arrested petitioners (R. 298).

5

There is no significant distinction between the charges

of trespass in Peterson, Lombard and Robinson, and the

charges of disturbing a public worship, which would justify

the reversal of trespass convictions while permitting peti

tioners’ convictions for disturbing worship to stand. As

set forth in the original petition, the source of disturbance

when petitioners entered Overton Park Auditorium was

not their conduct, but their color.

Having both reversed convictions on similar facts in

Peterson, Lombard and Robinson, and having on a number

of occasions reversed convictions of peaceful individuals

convicted of disturbing the peace because of the acts of

hostile onlookers, cf. Henry v. City of Rock Hill, 376 U. S.

776; Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229; Garner v.

Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, this Court, we respectfully submit,

ought not assume that the Tennessee Supreme Court would,

in the light of these decisions, apply the disturbance of

public worship statute to petitioners’ conduct. Barr v.

City of Columbia,----- U. S. —— (June 22, 1964).

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above and in the Petition for

Writ of Certiorari, it is respectfully urged that rehearing

be granted and that upon such rehearing, a Writ of Cer

tiorari issue to the Supreme Court of Tennessee. In addi

tion, petitioners respectfully submit that it would not be

inappropriate were this Court to enter an order vacating

the judgments and remanding the cases to the Supreme

Court of Tennessee for further proceedings in the light of

this Court’s decisions in Peterson v. City of Greenville,

Lombard v. Louisiana and Robinson v. Florida. Cf. Henry

v. City of Rock Hill, ----- U. S. ----- , 11 L. ed. 2d 38;

6

Randolph v. Virginia, 374 U. S. 97; Henry v. Virginia, 374

U. S. 98; Thompson v. Virginia, 374 U. S. 99; Wood v.

Virginia, 374 U. S. 100.

Respectfully submitted,

H. T. Lockhard

B. F. J ones

I. H. Murphy

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

D errick A. B ell, J r.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y., 10019

R. B. S ugarmon, J r.

B. L. H ooks

A. W. W illis

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

Of Counsel

7

Certificate o f Counsel

I hereby certify that the foregoing petition for rehearing

is presented in good faith and not for delay and is restricted

to grounds specified in Rule 58 of the Rules of this Court.

Attorney for Petitioners

9

APPENDIX

Pertinent excerpts from portions of original record in

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526.

H arold S. L ewis, Director of the Memphis Park Com

mission.

# # # # #

By Attorney Willis:

Q. [Referring to Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2] Will you read

the caption on there, what that list is all about! A. This

is the City-owned parks, operated by the Park Commission.

Q. All of the City parks! A. All of the City-owned

parks.

Q. All of the City-owned parks ? A. That’s right.

Q. Is it true that some of those parks are used by negroes

and others are used by whites! A. That is correct.

Q. Is it true that some of them are used by both races!

A. That is correct.

Q. Are you familiar with which ones are used by negroes

—18—

and which ones are used by whites? A. Yes.

—19—

# # # # #

Overton Park is white with the exception of the Zoo.

—24—

# # # # #

Q. When you speak of white and negro you mean that

negroes can not go in the park that is designated as white?

A. That is right.

Q. And white people can not go in the parks that are

designated for negroes? A. That is right.

Q. In the event negroes were in a park that was desig

nated as white what would be the policy? A. They would

be asked to leave.

10

Q. By whom? A. By the Park Director.

Q. The line is drawn clear and you all have instructed

your employees which parks negroes can not use? A.

That is right.

Q. And which parks white people can not use? A. Yes,

that is right.

—26—

# # # # #

Q. Again we would like to have you indicate on these lists

those [park facilities] which are used by negroes and which

by white? A. (Reading) “Golf Courses” :

—27—

# * # * #

Overton is for white.

—28—

# # # # #

Q. (Continuing) Now will you look at that list [Plain

tiffs’ Exhibit 3] and tell us what it is about? A. That is

the 1961 list of the playgrounds operated by the recreation

department of the Memphis Park Commission, controlled

by the Park Commission.

Q. Again we will go down that list and indicate those

used by negroes and those used by white and those that are

used by both, if any?

—31—

# # # # #

Overton is white.

—33—

# # # # #

Q. We had mentioned the park—Overton Park. I believe

the only thing used by both, the zoo? A. And art gallery.

Q. But are there dual sets of toilets out there? A. There

- 3 5 -

are dual sets of toilets.

Harold 8. Lewis—Direct

*# # #

— 36—

11

H arry P ierotti, Chairman of the Memphis Park Com

mission.

Q. Now, what about your plan for the future, Mr. Pier

otti? Does the Park Commission plan to open up other

facilities in the future? Have you evolved any plan with

—114-

regard to that? A. Mr. Prewitt, I think I can better ex

press that if I would read the plan which we have evolved,

so there won’t be any mistake about what our plan is for

the immediate future.

Q. All right, sir. Suppose you read that plan. A. (Read

ing)

“Having heretofore, before the filing of this suit, pro

vided twenty-one parks in the City on a non-segregated

basis, and having recently removed restrictions at

Overton Park Zoo, Art Gallery in Overton Park and

the Boat Dock at McKellar Lake, the Park Commis

sion, following a practice already adopted, has evolved

the following plan and the following facilities will be

open to all races without restrictions at the dates indi

cated.”

—115—

# # # # #

“Overton Park Golf Course, March 1st, 1963, . . . ”

—116-

Harry Pierotti—Direct

H a rold S. L ewis, Director of the Memphis Park Commis

sion.

# # # # #

By Attorney Preivitt:

Q. As testified by Mr. Pierotti, the Overton Park Zoo has

already—all restrictions about admittance of colored as well

as white has been removed? A. Right.

12

Q. So that both races may be admitted to the Overton

Park Zoo at any time the Zoo is open? A. Right.

Q. And that restriction was voluntarily removed by the

Park Commission in December of 1960? A. The day after

Thanksgiving, 1960.

Q. And the art gallery in Overton Park, the restriction

there was likewise removed a few months ago on a voluntary

basis? A. Right.

—167—

# # # # #

Q. I say they can use any place where the police do not

put them out? Is that your statement? A. The police do

not put them out there.

—184—

Q. I say if the police do not put them out of a particular

park, then they are free to use it? A. Certainly.

Q. They would not know, according to your testimony,

whether they are free to use it until the police asked them

to get out? A. That could be.

—185—

* # # # #

Q. Does the Park Commission have any policy of public

announcement when they integrate a facility? A. The

- 1 8 5 -

Park Commission’s policy has been to avoid any trouble as

to integrating without any fanfare, such as was done at the

Zoo.

Q. But there was an announcement that the Zoo was de

segregated, was there not? A. There was a very small an

nouncement, yes.

Q. As to these other integrated facilities that you men

tioned in your testimony, has there been any announcement

that negroes could use them?

# # * # #

Harold 8. Lewis—Direct

13

A. There was no announcement that negroes could use

them, nor was there an announcement that whites could

use places that had been for negroes.

—186—

Q. As I understand your testimony, the criteria is

whether or not the police arrest you or run you out? A. I

wouldn’t say that.

Q. What is the criteria? A. The criteria is the parks

are open to all races and they use them.

Q. How would the members of the public know that the

parks are open to all races if there is no announcement

made? A. By usage.

Q. If the police don’t run you out, as you said before?

A. By usage.

Q. You are saying that we are free to go to any park in

the City of Memphis that we wish to go to, as long as no

one runs us out, is that your testimony? A. As long as

no one asks you to leave.

Q. We are free to go to all of them as long as no one

asks us to leave? A. Yes.

Q. At the point that we are asked to leave, then what is

the policy? A. We are still operating under a segregated

park system in that case, and we would ask you to leave,

—187—

and if you caused trouble by not leaving, we would then

call the police.

Q. Who would have the authority to ask us to leave, any

member of the public, or would it have to be an employee

of the Park Department or the Police? A. Certainly any

member of the public could ask you, but it would have to be

park personnel to have any authority as far as the Park

Commission is concerned.

Q. Are you familiar with the location of Glenview Park?

A. I am.

Harold S. Lewis—Cross

*

14

Harold S. Lewis—Cross

Q. Negroes could go there and use that if they are not

asked to leave? A. They would be asked to leave.

Q. They would be asked to leave? A. That’s right.

Q. Who would ask them to leave? A. The Director of

the park or the police.

Q. If they peacefully refused to leave, what would be

the follow-up procedure of the Park Commission? A.

After being asked in every nice way known, the Park Di

rectors are instructed to call the Park Police.

Q. And have the negroes arrested? A. Have them

forcibly ejected or arrested, yes.

— 189—