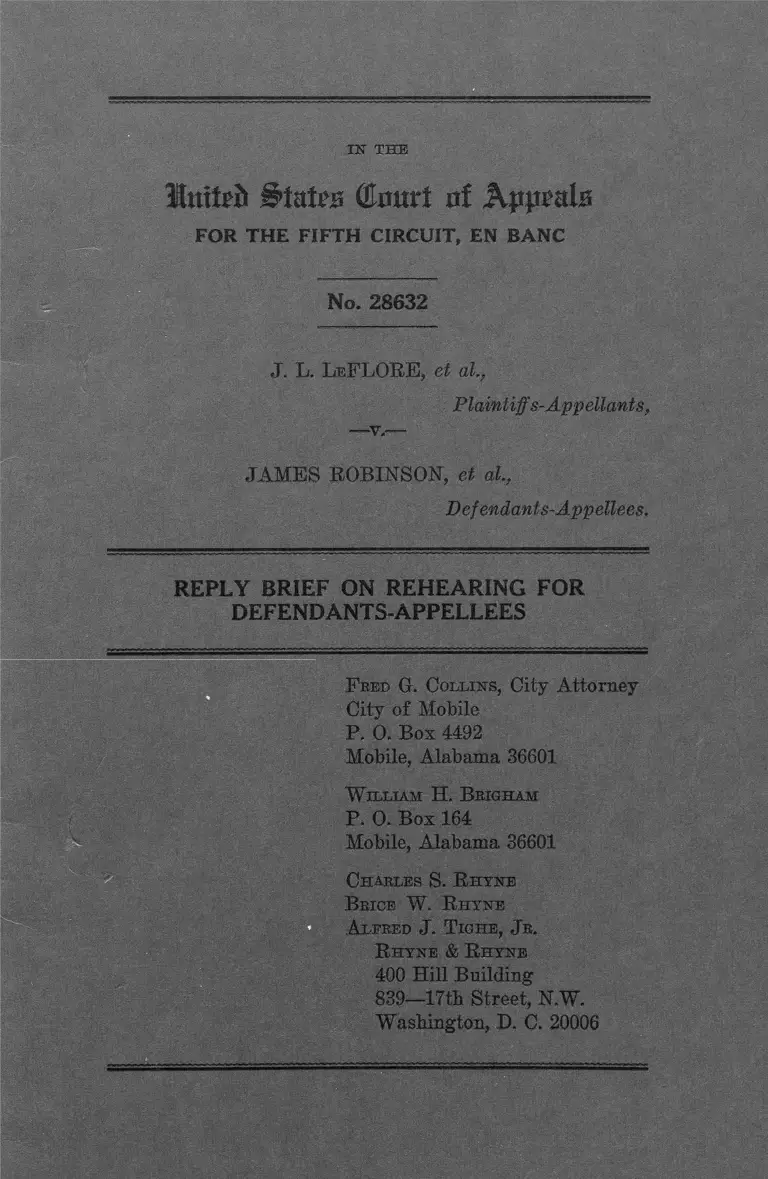

LeFlore v Robinson Reply Brief on Rehearing for Defendants-Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. LeFlore v Robinson Reply Brief on Rehearing for Defendants-Appellees, 1971. b8400f0b-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d1d9f03-bbcf-4713-afda-80d58daeef36/leflore-v-robinson-reply-brief-on-rehearing-for-defendants-appellees. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

IIS' TH E

Mnxtzb (ta rt of

F O R T H E F IF T H C IR C U IT , EN B A N C

No. 28632

J. L. LeFLORE, et al,,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,,

JAMES ROBINSON, et al,,

Defendants-Appellees,

REPLY BRIEF ON REHEARING FOR

DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES

F eed G. C ollins , City Attorney

City of Mobile

P. 0. Bos 4492

Mobile, Alabama 36601

W illiam H. B bigham

P. 0. Box 164

Mobile, Alabama 36601

C harles S. R h y n e

B rice W . R h y n e

A lfred J. T ig h e , Jr.

R h y n e & R h y n e

400 Hill Building

839—17th Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Reply Brief on Rehearing for Def'endants-Appellees 1

I— Supreme Court Holds That National Policy For

bids Federal Court Intervention By Injunction Or

Declaratory Judgment In State Court Prosecutions 2

II— Supreme Court Decisions Of February 23, 1971

Require This Court To Dismiss This Action To

Prevent Added Burdens On Federal Courts And

The United States Supreme Court As Argued In

The Initial Brief Of Mobile .................................. 5

A. Appellants’ Contention That They Meet The

Test For Federal Intervention Set Out In The

Recent U. S. Supreme Court Decisions Is With

out Merit ............................................................ 6

B. Is There A “ Case Or Controversy” Pending

Regarding Ordinance No. 14-11? If So, Do The

Recent U. S. Supreme Court Decisions Bar

Federal Intervention? ........................................ 9

C. Decisions of February 23, 1971 Revised “ Chill

ing Effect” And “ Vagueness And Over

breadth” Concepts ........................................... 10

D. Freedman’s Pure Speech Ruling On Review

Not Applicable H ere ........................................... 13

E. This Court Should Not Enter The Legislative

Field .................................................................... 13

III— Supreme Court Decisions Since Younger, et al.,

And Other Developments Since That Time Confirm

That The Decision Herein Must Be Vacated And

The Complaint Dismissed....................................... 17

A. Fifth Circuit Cases Decided On March 29, 1971 18

11

B. Cases In Other Circuits Applying The Absten

PAGE

tion Doctrine ....................................................... 19

C. Other Developments........................................... 21

C onclusion ......... . ..................................................................... 22

T able op A u thobities

Cases

ABC Boohs, Inc. v. Benson, 315 F. Supp. 695, U.S.

S. Ct. Docket No. 844, 39 L.W. 3423 ....................... 17, 20

Barlow v. Gallant, U.S. S. Ct. Docket No. 90, 39 L.W.

3423 ........................................................................... 17

Beal v. Missouri Pacific Railroad Corp., 312 U.S. 45

(1941) ................................................ 7

Boyle v. Landry, 91 S. Ct. 758 .......................... 1, 4, 8, 15, 20

Brown v. Fallis, 311 F. Supp. 548, U.S. S. Ct. Docket

No. 5412, 39 L.W. 3423 . ............................................ 17, 21

Buchanan v. Wade, U.S. S. Ct. Docket No. 290, 39

L.W. 3423 ....................................... 17

Byrne v. Karalexis, 91 S. Ct. 777 ................................1, 4,13

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940) ........... 12

Cato v. Georgia, 302 F. Supp. 1143, U.S. S. Ct.

Docket No. 31, 39 L.W. 3423 .................................... 17,18

Chicago <& Southern Air Lines v. Waterman S. S.

Corp., 333 U.S. 103, 68 S. Ct. 431 (1948) ............... 15

Demich, Inc. v. Ferdon, 426 F. 2d 643, U.S. S. Ct.

Docket No. 500, 39 L.W. 3423 ................................ 17, 20

DeRenzy v. Cahill,-426 F. 2d 643, U.S. S. Ct. Docket

No. 500, 39 L.W. 3423 .. ........................................... 17

Dombrowslci v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) . . . . . .10 , 11,12

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157 (1943) . . . 7

Dyches v. Ryan, U.S. S. Ct. Docket No. 5164, 39 L.W.

3423 ........................................................................... 17

Dyson v. Stein, 91 S. Ct. 769 ........................ 1, 4, 8, 9, passim

Embry v. Allen, 422 F. 2d 1158, U.S. S. Ct. Docket

No. 5539, 39 L.W. 3424 ........................................... 17,19

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) ........................ 7

Fenner v. Boykin, 271 U.S. 240 (1926)....................... 7

Fernandes v. Mackell, 91 S. Ct. 764 ...................1,18, 19, 20

Freedm.an v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51, 13 L. Ed. 2d 649

(1965) ...................................................................... 13

Geiger v. Jenkins, 316 F. Supp. 370, U.S. S. Ct.

Docket No. 5952, 39 L.W. 3423 ................................ 17,19

Goodman v. Wheeler, 306 F. Supp. 58, U.S. S. Ct.

Docket No. 102, 39 L.W. 3423 .................................. 17

Ilosey v. City of Jackson, 309 F. Supp. 527, U.S. S.

Ct. Docket No. 134, 39 L.W. 3423 ............................ 17,19

Hunter v. Allen, 422 F. 2d 1158, U.S. S. Ct. Docket

No. 5539, 39 L.W. 3423 ............................................. 17,18

In Re Wright, 251 F. Supp. 880 (M.D. Ala. 1965) . . . . 9

Johnnie Reb’s Book <& Card Shop v. Slaton, U.S. S.

Ct. Docket No. 217, 39 L.W. 3423 ............................ 17

Landry v. Daley, 280 F. Supp. 938 (D.C. N.D. 111.

1968) ......................................................................... 14-15

LeClah v. O’Neil, U.S. S. Ct. Docket No. 112, 39 L.W.

3423 ........................................................................... 17

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Crancli) 137, 2 L. Ed.

60 (1803) .................................................................... 14

McGrew v. City of Jackson, 307 F. Supp. 751, U.S.

S. Ct. Docket No. 116, 39 L.W. 3423 ....................... 17,18

Natali v. San Francisco, 426 F. 2d 643, U.S. S. Ct.

Docket No. 500, 39 L.W. 3423 .................................... 17

North v. Greene, Dist. Ct. No. 413-17, March 18, 1971,

Dist. of Columbia....................................................... 21

Ohio v. Wyandotte Chemicals Corporation, U.S. S.

Ct. Docket No. 41, 39 L.W. 4323, March 23, 1971 .. 21

Pauling et al. v. McNamara et al., 331 F. 2d 796

(1964), cert. den. 377 U.S. 933 ................................. 15

Peres v. Ledesma, 91 S. Ct. 674 ............................ 1, 3, 13,18

Porter v. Kimsey, 309 F. Supp. 993, U.S. S. Ct.

Docket No. 5462, 39 L.W. 3423 ................................ 17,18

I l l

PAGE

IV

Rollins v. Shannon, 292 F. Supp. 580, U.S. S. Ct.

Docket No. 5013, 39 L.W. 3423 .............................. 17, 20

Samuels v. Mackell, 91 S. Ct. 764 ........................ 1, 3,10,18,

passim

Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147 (1939) ..................... 12

Shevin v. Lazarus, U.S. S. Ct. Docket No. 43, 39 L.W.

3423 ............................................................................... 17

Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U.S. 1 1 7 ............................ 18

Stein v. Bachelor, 300 F. Supp. 602 (N.D. Tex. 1969) 9

United Mine Workers of America, Dist. 12 v. Illinois

Bar Ass’n., 389 U.S. 217 (1967) ................................... 12

Wade v. Buchanan, U.S. S. Ct. Docket No. 289, 39

L.W. 3423 ...................................................................... 17

Watson v. Buck, 313 U.S. 387 (1941) ............................ 7

Wheeler v. Goodman, 306 F. Supp. 58 (Docket No.

102) ................................................................................................. 19

Wright v. City of Montgomery, 282 F. Supp. 291, 406

F. 2d 867, U.S. S. Ct. Docket No. 20, 39 L.W. 3423 17,18

Younger v. Harris, 91 S. Ct. 746 ............................ 1, 3, 5, 6,

passim

PAGE

United States Code

28 U.S.C. § 2283 .......................................................... 2, 4

42 U.S.C. § 1983 (1871 Civil Eights Act) ................. 3, 4

Mobile City Code

14-7; 14-11, 14-13; 14-051 et seq..........................9,10, 13,22

Legislative History

1 The Records of the Federal Convention 1787 (Far-

rand ed. 1911) 21 ..................................................... 14

IN' THE

Ilnxtzb i ^ t a t e © c u r t rtf A p p e a l s

For the Fifth Circuit, En Banc

No. 28632

------------- -— _+-------------------

J. L. L eF lore, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

J am es R obinson , et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

--------------------------- 4---------------------------

REPLY BRIEF ON REHEARING FOR

DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES

This Reply Brief of Defendants-Appellees, City of Mobile,

Alabama et al. (Mobile) pursuant to order of the Court,

dated March 2, 1971, discusses the impact of the decisions

of the United States Supreme Court, announced February

23,1971, in Younger v. Harris, 91 S. Ct. 746; Perez v. Ledes

ma, 91 S. Ct. 674; Samuels v. Mackell and Fernandez v.

Mackell, 91 S. Ct. 764; Dyson v. Stein, 91 S. Ct. 769; Byrne v.

Karalexis, 91 S. Ct. 777; and Boyle v. Landry, 91 S. Ct. 758,

and is also addressed to arguments advanced in the Brief

For Appellants.

Since many of the arguments advanced in our Initial

Brief filed February 12, 1971 were affirmed by the Supreme

Court decisions of February 23, 1971 and many of the

arguments advanced in the Brief for Appellants were antic

ipated in our Initial Brief, we shall refer whenever possible

to our Initial Brief (I.B.) to avoid undue repetition.

2

We have read and studied Appellants latest brief and fail

to find reference or answer therein to the arguments we set

out in our brief of February 12, 1971.

We herewith reaffirm the arguments made in that brief.

We note particularly that our arguments for the proposition

that the anti-injunction statute (28 U.S.C. §2283) were un

necessary in view of the decisions of the Supreme Court on

February 23, 1971 wherein in matters involving these same

questions the Court stated that the abstention principle for

which we argued in our Point No. II, pp. 23-27, is funda

mental to the Constitution, and the Federalism that our

Founding Fathers had in mind. Thus, the principle is so

fundamental that the passage of a statute by the Congress

for its enforcement is unnecessary.

I.

Supreme Court Holds That National Policy Forbids

Federal Court Intervention By Injunction Or Declara

tory Judgment In State Court Prosecutions.

On February 23, 1971 the Supreme Court of the United

States, affirming the long standing ‘ ‘ Abstention Doctrine,”

held that a federal court should not issue an injunction to

stay proceedings pending in a state criminal court, or grant

relief by way of declaratory judgment, except under very

unusual and special circumstances where necessary to pre

vent immediate irreparable injury.

Resting solely on “ comity” and the absence of factors

necessary under equitable principles to justify federal inter

vention, and without considering whether 28 U.S.C. §2283

which prohibits an injunction against state court proceed

ings “ except as expressly authorized by Act of Congress”

would in and of itself be controlling . . . ” , the Court, on

February 23, 1971 rejected lower federal court intervention

in state court prosecutions in the six cases decided. The

Court in each case reversed or vacated each lower federal

court determination as to the unconstitutionality or con

3

stitutionality respectively of the state statutes or ordinances

challenged. Specifically the Court found as follows:

(1) Younger v. Harris, 91 S. Ct. 746. Reversed and re

manded. Even if California Criminal Syndicalism Act under

which one of the plaintiffs was being prosecuted was un

constitutional, Federal district court should not have en

joined California prosecution not involving harassment and

not threatening great and immediate, irreparable harm that

cannot be eliminated in state prosecution; 1871 Civil Rights

Act (42 U.S.C. §1983) plaintiff being prosecuted by state

was not entitled to federal court equitable relief against

prosecution in state court where the injury he faced was

solely that incidental to every criminal proceeding brought

lawfully and in good faith; Civil Rights Act plaintiffs who

claim that prosecution of another person chills their exer

cise of First Amendment rights, but who have neither been

prosecuted nor threatened with prosecution under statute,

have no standing to attack it.

(2) Peres v. Ledesma, 91 S. Ct. 674. Reversed insofar

as grants injunctive relief. Vacated and remanded. Federal

district court improperly intruded into the States criminal

processes and should not have suppressed allegedly obscene

materials seized by state officials during course of good-

faith obscenity prosecution; U. S. Supreme Court unable to

review decision of three-judge court that local ordinance

was invalid because it has no jurisdiction to review on direct

appeal the validity of a declaratory judgment against a

local ordinance.

(3) Samuels v. Machell, 91 S. Ct. 764. Affirmed. Where

defendants in state court prosecutions under state criminal

anarchy statutes brought federal action seeking to enjoin

state prosecutions and also seeking declaratory judgment

that statutes were invalid, three-judge federal court should

not have considered constitutionality of New York Criminal

Anarchy Law nor right to injunction against prosecution

of defendant who did not show harassment or threat of

irreparable damage.

4

(4) Dyson v. Stein, 91 S. Ct. 769. Vacated and remanded.

Three-judge Federal district court should not have declared

Texas obscenity statute unconstitutional and enjoined news

paper publisher’s prosecution and any other prosecution

under state statute in absence of finding of irreparable

injury.

(5) Byrne v. Karalexis, 91 S. Ct. 777. Vacated and re

manded. Three-judge Federal district court’s grant of pre

liminary injunctive relief against pending or future state

obscenity prosecutions based on probability of success in

having state statute declared unconstitutional and that

appellees might suffer irreparable injury if they were un

able to show “ I am Curious (Yellow)” , was rendered im

proper by the court’s failure to find that the movie ex

hibitor’s First Amendment rights could not be adequately

protected in single state criminal prosecution.

(6) Boyle v. Landry, 91 S. Ct. 758. Reversed and re

manded. Chicago citizens who allege that possibility of

their state prosecution under Illinois intimidation statute,

which three-judge Federal district court declared uncon

stitutional and enjoined enforcement, intimidates them in

their exercise of First Amendment rights but who have not

been charged, arrested or even threatened with prosecution,

have no standing to bring 1871 Civil Rights Act suit for

declaratory and injunctive relief against statute.

Mobile submits, that the Supreme Court decisions pre

cluding Federal Court intervention in state court criminal

proceedings on equitable principles alone, reinforced by the

legislative rule of 22 U.S.C. §2283, as argued in its Initial

Brief, pp. 9-23, clearly require this Court to vacate the

majority opinion of the three-judge panel of this Court

and dismiss the complaint. The basic requirement of equity

jurisprudence required to be present to justify Federal

intervention are simply not here present.

5

Supreme Court Decisions Of February 23, 1971 Re

quire This Court To Dismiss This Action To Prevent

Added Burdens On Federal Courts And The United

States Supreme Court As Argued In The Initial Brief

Of Mobile.

As stated by the Supreme Court in the Younger decision

“ A federal lawsuit to stop a prosecution in a state court

is a serious matter. And persons having no fears of state

prosecution except those that are imaginary or speculative,

are not to be accepted as appropriate plaintiffs in such

cases” 91 S. Ct. at 749.

“ Our Federalism” requires sensitivity to the legitimate

interests of both the State and the National Governments.

State courts must be permitted to try state cases free from

interference by federal courts.

As was stated in Younger, supra, the U. S. Supreme Court

held that “ Without regard to . . . the constitutionality of

the state law, we have concluded that the judgment of the

District Court, enjoining appellant Younger from prose

cuting . ., must be reversed as a violation of the national

policy forbidding federal courts to stay or enjoin pending

state court proceedings except under special circum

stances.” {supra, p. 749) (emphasis supplied)

Contrary to the assertion of Appellants (Brief p. 5) the

Supreme Court decisions of Febi'uary 23, 1971 not only

affect the decision herein but require that it be vacated and

the complaint dismissed.

The facts in this case clearly show:

(1) The protest activities of the Neighborhood Organized

Workers (N.O.W.) beginning in 1968 are not here involved.

It is not alleged that Mobile did anything to hamper the

plaintiffs pure freedom of speech (I.B. 2).

(2) The confrontation of the “ speech conduct” of the

Plaintiffs with the general public interest ordinances of

II.

6

Mobile here involved springs from events leading np to

and centered around the 1969 “ Americas Junior Miss

Pageant” (I.B. 2).

(3) For violating Mobile ordinances, ninety-one persons

were arrested on May 1, 1969 (R. 131-134); one hundred

forty-eight on May 2, 1969 (R. 134-138, 219a); and sixty-

four on May 3,1969 (R. 138-140) (I.B. 2). Appellants admit

that these arrests and state court prosecutions, precipitated

this suit (Appellants’ Brief 10).

(4) On May 5, 1969, while the Municipal Court prosecu

tions were pending, six plaintiffs, only three of whom were

arrested on May 1, 2 or 3, 1969 filed this class action in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

Alabama, Southern Division on their behalf and the behalf

of all others similarly situated who allegedly find their

rights in jeopardy because of the enforcement, threatened

enforcement, and arbitrary and capricious application of

the law by the defendants. The class purported to be rep

resented by the Plaintiffs “ consists of those who have been,

and who will be subjected to arrest and prosecution under

certain ordinances of the City of Mobile, Alabama that are

unconstitutional on their face and as applied” (R. 37)1

(I.B. 3).

(5) Prosecutions for the arrests of May 1, 2, and 3, 1969

remain pending in the municipal court pursuant to stipula

tion between the parties pending disposition of this case.

A. Appellants’ Contention That They Meet The Test

For Federal Intervention Set Out In The Recent

U. S. Supreme Court Decisions Is Without Merit

In Younger, supra (pp. 751, 752), the U. S. Supreme

Court first pointed to its many decisions on abstention,

based on comity (Federalism) and then defined the absten

tion test as follows:

1 Whether or not Plaintiffs now seek to restrict themselves to being

“ . . . representatives of a class of the black residents of Mobile,

Alabama . . .” is not clear. Appellant’s Brief 2.

7

In all of these cases the Court stressed the im

portance of showing irreparable injury, the tradi

tional prerequisite to obtaining an injunction. In

addition, however, the Court also made clear that

in view of the fundamental policy against federal

interference with state criminal prosecutions, even

irreparable injury is insufficient unless it is “ both

great and immediate.” Fenner, supra. Certain types

of injury, in particular, the cost, anxiety, and incon

venience of having to defend against a single crim

inal prosecution, could not by themselves be con

sidered “ irreparable” in the special legal sense of

■that term. Instead, the threat to the plaintiff’s fed

erally protected rights must be one that cannot be

eliminated by his defense against a single criminal

prosecution. See, e.g., Ex parte Young, supra, 209

U.S. at 145-147, 28 S. Ct. at 447-449. Thus, in the

Buck case, supra, 313 U.S., at 400, 61 S. Ct., at 966,

we stressed:

“ Federal injunctions against state criminal stat

utes, either in their entirety or with respect to

their separate and distinct prohibitions, are not to

be granted as a matter of course, even if such

statutes are unconstitutional. ‘ No citizen or mem

ber of the community is immune from prosecution,

in good faith, for his alleged criminal acts. The

imminence of such a prosecution even though al

leged to be unauthorized and hence unlawful is not

alone ground for relief in equity which exerts its

extraordinary powers only to prevent irreparable

injury to the plaintiff who seeks its aid.’ Beal v.

Missouri Pacific Railroad Corp., 312 U.S. 45, 49,

61 S. Ct. 418, 420, 85 L. Ed. 577.”

And similarly, in Douglas, supra, we made clear,

after reaffirming this rule, that:

“ It does not appear from the record that peti

tioners have been threatened with any injury other

8

than that incidental to every criminal proceeding

brought lawfully and in good faith * * V ’ 319 U.S.,

at 164, 63 S. Ct., at 881. (Emphasis supplied)

The Court in Younger (91 S. Ct. at 749, 750) and in

Boyle (91 S. Ct, 758, 760) also held that one not subject to

state prosecution are not appropriate plaintiffs in a Fed

eral action. See also Dyson v. Stein, 91 S. Ct. 769, 775

(Douglas dissenting),

As we apply this language to the situation in Mobile, we

submit that the city officials have acted in good faith and

that in the pending actions, including any which might be

construed as threats, Appellants have not “ been threatened

with any injury other than that incidental to every criminal

proceeding brought lawfully and in good faith * * * ”

{Younger, supra, p. 752). Nothing in this record even ap

proaches the “ Vietnamese” raid described by Mr. Jus

tice Douglas in his dissent in Dyson v. Stein, 91 S. Ct. 769,

772, where no irreparable injury was found, or the “ official

lawlessness” referred to by Mr. Justice Stewart, with whom

Mr. Justice Harlan joined, concurring in Younger v. Harris,

91 S. Ct. 746, 757. As admitted by Appellants (Brief 10)

only three of the six plaintiffs were being prosecuted in

the municipal court for the action which “ precipitated this

suit” . The prosecutions, by stipulation, are being continued

pending disposition of this suit.

Appellants’ position that they meet the test of bad faith

harassment, showing of irreparable injury immediate and

great as set out in Younger el at., supra is clearly without

merit. At the same time, they contend the federal district

court and this Court should rule that the ordinances involved

are unconstitutional on their face and on that basis they will

have the “ chilling effect” upon the enjoyment of their con

stitutional rights. In other words, Appellants, in one

breath, contend the facts of record exist on the point, and,

in another, ask this Court to rule as to the constitutionality

of the ordinances involved merely by study and analysis of

their “ facial” appearance regardless of the facts. In short,

9

the Court is requested by Appellants to exercise a legislative

veto over the passage by the City of Mobile of these ordin

ances. This is not a proper function of this Court.

B. Is There A “ Case Or Controversy” Pending Regard

ing Ordinance No. 14-11? If So, Do The Recent

U. S. Supreme Court Decisions Bar Federal Inter

vention?

Appellants contend there is a “ case or controversy’ ’ in

this case involving Mobile Ordinance Section 14-11. At the

same time they make the point that there were no prosecu

tions pending against any of the plaintiffs or the members

of their class under this ordinance. We submit that the

Appellants have not shown this court a proper basis for

federal intervention as to this ordinance as a “ case or con

troversy” .

The majority opinion of this Circuit’s panel in this matter

rendered its opinion as to the constitutionality of Sec. 14-11

solely on the basis of its “ facial” appearance. By the

Appellants’ own admission (See Appellants’ Initial Brief

25-26, footnote 21), an identical ordinance of Montgomery

was held “ valid on its face.” hi Re Wright, 251 F. Supp.

880 at 882 (M.D. Ala. 1965). There was no finding, discus

sion or application of any Mobile record fact in this opinion

relative to Sec. 14-11.

Judge Goldberg stated in footnote 6:

Since no prosecutions are currently pending under

Section 14-11 of the Mobile ordinances, there is no

question about the availability of injunctive relief

against future action under the ordinance. Stein v.

Bachelor, supra.

The Supreme Court of the United States in Dyson v.

Stein, 91 S. Ct. 769 (sub. nom. Stein v. Bachelor) vacated

and remanded that decision of the three-judge court on the

ground that no irreparable injury was found.

To this we refer to the language of the U. S. Supreme

Court in Younger, supra, wherein that Court comments

10

against the role of the judicary to veto the legislative pro

cess. The appropriate language of that Court as to the

contentions raised by Appellants herein as to Sec. 14-11 is

as follows (supra, 91 S. Ct. at pp. 754, 755):

Ever since the Constitutional Convention rejected

a proposal for having members of the Supreme Court

render advice concerning pending legislation it has

been clear that, even when suits of this kind involve

a “ case or controversy” sufficient to satisfy the re

quirements of Article 111 of the Constitution, the task

of analyzing a proposed statute, pinpointing its

deficiencies, and requiring correction of these de

ficiencies before the statute is put into effect, is rarely

if ever an appropriate task for the judiciary. (Em

phasis supplied)

C. Decisions of February 23, 1971 Revised “ Chilling

Effect” And “Vagueness And Overbreadth” Con

cepts

The Dombrotvski criteria and its “ chilling effect” theory

is all but stricken from future consideration by the United

States Supreme Court’s majority decisions in Younger,

Samuels, et al.

Without further discussion, we feel the following lan

guage of Mr. Justice Black in Younger, (supra at pp. 753,

754) fully deals with questions within the general sphere

of the cases dealing with the “ chilling effect” and “ vague

ness and overbreadth” concepts. This reads as follows:

The District Court, however, thought that the

Dombrowski decision substantially broadened the

availability of injunctions against state criminal

prosecutions and that under that decision the federal

courts may give equitable relief, without regard to

any showing of bad faith or harassment, whenever

a state statute is found “ on its face” to be vague or

overly broad, in violation of the First Amendment.

We recognize that there are some statements in the

11

Dombrowski opinion that would seem to support this

argument. But as we have already seen, such state

ments were unnecessary to the decision of that case,

because the Court found that the plaintiffs had al

leged a basis for equitable relief under the long-

established standards. In addition, we do not regard

the reasons adduced to support this position as suf

ficient to justify such a substantial departure from

the established doctrines regarding the availability

of injunctive relief. It is undoubtedly true, as the

Court stated in Dombrowski, that “ A criminal

prosecution under a statute regulating expression

usually involves imponderables and contingencies

that themselves may inhibit the full exercise of First

Amendment freedoms.” 380 IT.S., at 486, 85 S. Ct.,

at 1120. But this sort of “ chilling effect,’ ’ as the

Court called it, should not by itself justify federal

intervention. In the first place, the chilling effect

cannot be satisfactorily eliminated by federal in

junctive relief. In Dombrowski itself the Court stated

that the injunction to be issued there could be lifted

if the State obtained an “ acceptable limiting con

struction” from the state courts. The Court then

made clear that once this was done, prosecutions

could then be brought for conduct occurring before

the narrowing construction was made, and proper

convictions could stand so long as the defendants

were not deprived of fair warning. 380 U. S., at 491,

n. 7, 85 S. Ct., at 1123. The kind of relief granted in

Dombrowski thus does not effectively eliminate un

certainty as to the coverage of the state statute and

leaves most citizens with virtually the same doubts

as before regarding the danger that their conduct

might eventually be subjected to criminal sanctions.

The chilling effect can, of course, be eliminated by an

injunction that would prohibit any prosecution what

ever for conduct occurring prior to a satisfactory re

writing of the statute. But the States would then be

stripped of all power to prosecute even the socially

12

dangerous and constitutionally unprotected conduct

that had been covered by the statute, until a new

statute could be passed by the state legislature and

approved by the federal courts in potentially lengthy

trial and appellate proceedings. Thus, in Dombrow-

shi itself the Court carefully reaffirmed the principle

that even in the direct prosecution in the State’s own

courts, a valid narrowing construction can be applied

to conduct occurring prior to the date when the nar

rowing construction was made, in the absence of fair

warning problems.

Moreover, the existence of a “ chilling effect,” even

in the area of First Amendment rights, has never

been considered a sufficient basis, in and of itself,

for prohibiting state action. Where a statute does

not directly abridge free speech, hut—while regulat

ing a subject within the State’s power—-tends to have

the incidental effect of inhibiting First Amendment

rights, it is well settled that the statute can he upheld

if the effect on speech is minor in relation to the need

for control of the conduct and the lack of alternative

means for doing so. Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147,

60 S. Ct. 146, 84 L. Ed. 155 (1939); Cantwell v.

Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296, 60 S. Ct. 900, 84 L. Ed. 1213

(1940); United Mine Workers of America, Dist. 12

v. Illinois Bar. Ass’n., 389 U.S. 217 88 S. Ct. 353, 19

L. Ed. 2d 426 (1967). Just as the incidental “ chilling

effect” of such statutes does not automatically render

them unconstitutional, so the chilling effect that ad

mittedly can result from the very existence of certain

laws on the statute books does not in itself justify pro

hibiting the State from carrying out the important

and necessary task of enforcing these laws against

socially harmful conduct that the State believes in

good faith to be punishable under its laws and the

Constitution. (Emphasis Supplied)

The Court further pointed out that the eases dealing with

standing to raise claims of vagueness or overbreadth failed

13

to change the basic principles governing the propriety of

injunctions against state criminal prosecutions. (See foot

note 4, Younger, supra, p. 752).

D. Freedman’s Pure Speech Ruling On Review

Not Applicable Here

The Appellants’ challenge (Brief 28) to the Mobile

parade ordinance, Code §14-051, because it does not have a

constitutional provision for immediate judicial review, m

which they again rely on Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S.

51, 13 L. Ed. 2d 649 (1965), is clearly put to rest by the

U. S. Supreme Court in its pure speech decisions on Feb

ruary 23, 1971, in Byrne v. Karalexis, 91 S. Ct. 777 (Massa

chusetts Obscenity statute, “ I am Curious Yellow” ) ;

Dyson v. Stein, 91 S. Ct. 769 (Texas obscenity statute,

underground newspaper); and Perez v. Ledesma, 91 S. Ct.

674 (Louisiana prosecutions for violation of obscenity stat

ute and municipal ordinances). In each of these cases the

Supreme Court under the “ Abstention Doctrine” vacated

and remanded the decisions by the Federal Courts without

reference to any specific provision of the statutes which

had been held constitutional or unconstitutional. Again, the

Supreme Court held that state courts can best determine

all phases of the constitutionality of these laws, including

provisions for review.

E. This Court Should Not Enter The Legislative Field

In effect, Appellants contend that this Court should enter

the legislative field. In their original brief Appellants re

quested this Court to rule that twenty-one (21) of the ordi

nances of the City of Mobile are facially unconstitutional.

We respectfully submit that not only has the U. S. Su

preme Court decided on February 23, 1971 that this is not

a proper field for the Federal District and Circuit Courts

in the concept of Federalism; but we know, that in their

wisdom, members of this Court have no desire to enter the

legislative field.

14

As germane to this significant point we quote from

Younger v. Harris, 91 S. Ct. 746, at 754, 755 as follows:

Procedures for testing the constitutionality of a

statute “ on its face” in the manner apparently con

templated by Dombrowski, and for then enjoining all

action to enforce the statute until the State can ob

tain court approval for a modified version, are funda

mentally at odds with the function of the federal

courts in our constitutional plan. The power and

duty of the judiciary to declare laws unconstitutional

is in the final analysis derived from its responsibility

for resolving concrete disputes brought before the

courts for decision; a statute apparently governing

a dispute cannot he applied by judges, consistently

with their obligations under the Supremacy Clause,

when such an application of the statute would con

flict with the Constitution. Marbury v. Madison, 5

U.S. (1 Crunch) 137, 2 L. Ed. 60 (1803). But this

vital responsibility, broad as it is, does not amount

to an unlimited power to survey the statute books

and pass judgment on laws before the courts are

called upon to enforce them. Ever since the Consti

tutional Convention rejected a proposal for having

members of the Supreme Court render advice con

cerning pending legislation [fn. See 1 The Records

of the Federal Convention 1787 (Farrand ed. 1911)

21.] it has been clear that, even when suits of this

kind involve a “ case or controversy” sufficient to

satisfy the requirements of Article III of the Con

stitution, the task of analysing a proposed, statute,

pinpointing its deficiencies, and, requiring correction

of these deficiencies before the statute is put into

effect, is rarely if ever an appropriate task for the

judiciary. The combination of the relative remote

ness of the controversy, the impact on the legislative

process of the relief sought, and above all the specu

lative and amorphous nature of the required line-

by-line analysis of detailed statutes, see, e.g., Landry

15

v. Daley, 280 F. Supp. 938 (D.C.N.D. 111. 1968), re

versed sub nom., Boyle v. Landry, 400 U.S. —, 91

S. Ct. 758, 27 L. Ed. 2d — ordinarily results in a

kind of case that is wholly unsatisfactory for decid

ing constitutional questions, whichever way they

might be decided. In light of this fundamental con

ception of the Framers as to the proper place of the

federal courts in the governmental processes of pass

ing and enforcing laws, it can seldom be appropriate

for these courts to exercise any such power of prior

approval or veto over the legislative process. (Em

phasis supplied)

Analogous to the situation with which we are confronted

in the case at bar are the comments on the limitations on

judicial power by the Chief Justice of the United States

Warren Burger while he was sitting as a member of the

United States Court of Appeals for the District of Colum

bia in Pauling v. McNamara, 331 F. 2d 796, 798 (1964),

cert. den. 377 U.S. 933, 12 L. Ed. 2d 297:

* * * The language of the Court in Chicago &

Southern Air Lines v. Waterman S.S. Corp., 333

U.S. 103, 111, 68 S. Ct. 431, 92 L. Ed. 568 (1948),

is very much in point here:

“ Such decisions are wholly confided by our Con

stitution to the political departments of the gov

ernment, Executive and Legislative. They are deli

cate, complex, and involve large elements of proph

ecy. They are and should be undertaken only by

those directly responsible to the people whose

welfare they advance or imperil. They are deci

sions of a kind for which the Judiciary has neither

aptitude, facilities nor responsibility and which

has long been held to belong in the domain of

political power not subject to judicial intrusion or

inquiry.” [Citing cases]

That appellants now resort to the courts on a

vague and disoriented theory that judicial power

16

can supply a quick and pervasive remedy for one of

mankind’s great problems is no reason why we as

judges should regard ourselves as some kind of

Guardian Elders ordained to review the political

judgments of elected representatives of the people.

In framing policies relating to the great issues of

national defense and security, the people are and

must be, in a sense, at the mercy of their elected

representatives. But the basic and important corol

lary is that the people may remove their elected rep

resentatives as they cannot dismiss United States

Judges. This elementary fact about the nature of

our system, which seems to have escaped notice occa

sionally must make manifest to judges that we are

neither gods nor godlike, but judicial officers with

narrow and limited authority. Our entire System of

Government would sutler incalculable mischief should

judges attempt to interpose the judicial will above

that of the Congress and President, even were we

so bold as to assume that we can make better deci

sions on such issues. (Emphasis supplied)

It is crystal clear that Federal courts are not, and cannot

be, legislative rule making bodies. “ Our Federalism” pre

cludes intervention by federal courts in state criminal pro

ceedings except under the unusual and special circumstances

where necessary to prevent immediate and great irrepar

able injury. No such circumstances are, nor can they be,

here presented. Appellants’ contention that they meet the

test for federal intervention set out in the Supreme Court’s

decisions of February 23, 1971 is without merit.

17

III.

Supreme Court Decisions Since Younger, et al., And

Other Developments Since That Time Confirm That

The Decision Herein Must Be Vacated And The Com

plaint Dismissed.

On February 23, 1971 the Supreme Court of the United

States decided six cases, involving seven docketed cases,

upholding the “ Abstention Doctrine” . Mr. Justice Black,

Circuit Justice of the Fifth Circuit, wrote the majority

opinion in five of the decisions and participated in the re

maining two per curiam decisions.

At least nineteen (19) decisions of the U. S. Supreme

Court since February 23, 1971 have applied the principle

of “ abstention” .2

2 These cases decided March 29, 1971, reported at 39 U SLW 3423-

24, involving abstention are: (1 ) Docket No, 20, Wright v. City of

Montgomery, 282 F. Supp. 291, 406 F. 2d 867, Fifth Circuit (dis

orderly conduct, loitering, obedience to orders) ; (2 ) Docket No. 31,

Cato v. Georgia, 302 F. Supp. 1143, Fifth Circuit (operating a lottery,

electronic device discovery) ; (3 ) Docket No. 43, Shevin v. Lazarus;

(4 ) Docket No. 90, Barlow v. Gallant; (5 ) Docket No. 102, Goodman

v. Wheeler, 306 F. Supp. 58, Fourth Circuit (vagrancy statute); (6 )

Docket No. 112, LeClah v. O’Neil; (7 ) Docket No. 116, McGrew v.

City of Jackson, 307 F. Supp. 751, Fifth Circuit (obscenity) ; (8 )

Docket No. 134, Hosey v. City of Jackson, 309 F. Supp. 527, Fifth

Circuit (obscenity); (9 ) Docket No. 217, Johnnie Reb’s Book & Card

Shop v. Slaton; (10) Docket No. 289, Wade v. Buchanan; (11)

Docket No. 290, Buchanan v. Wade; (12) Docket No. 500, Demich,

Inc. v. Ferdon, De Rensy v. Cahill, and Natali v. San Francisco, 426

F. 2d 643, Ninth Circuit (obscenity) ; (13) Docket No. 844, ABC

Books, Inc. v. Benson, 315 F. Supp. 695, Sixth Circuit (obscenity) ;

(14) Docket No. 5013, Rollins v. Shannon, 292 F. Supp. 580, Eighth

Circuit (unlawful assembly) ; (15) Docket No. 5164, Dyches v. Ryan;

(16) Docket No. 5412, Brown v. Fattis, 311 F. Supp. 548, Tenth

Circuit (obscenity); (17) Docket No. 5462, Porter v. Kimzey, 309

F. Supp. 993 (defamation statute); (18) Docket No. 5539, Embry v.

Allen, Reported as Hunter v. Allen, 286 F. Supp. 830, 422 F. 2d 1158,

Fifth Circuit (disorderly conduct) ; and (19 ) Docket No. 5952, Geiger

v. Jenkins, 316 F. Supp. 370, Fifth Circuit (license to practice medi

cine).

1 8

A. Fifth Circuit Cases Decided On March 29, 1971.

The seven (7) eases which were decided involving the

Fifth Circuit are summarized as follows:

(1) Wright v. City of Montgomery, 282 F. Supp. 291, 406

F. 2d 867 (Docket No. 20). This case involves alleged viola

tions of disorderly conduct, loitering and obedience to

orders ordinances. This case involves to a certain extent

ordinances of the same general nature as those involved in

the case at bar, and was referred to in our Initial Brief at

pp. 12,13, 41, 42, 43. The Federal District Court (N.D. Ala.)

denied relief. This Court affirmed. U. S. Supreme Court

granted certiorari, vacated the judgment and remanded to

the U. S. Circuit Court for the Fifth Circuit for reconsidera

tion in the light of Younger, Samuels and Fernandez, supra.

(2) Cato v. Georgia, 302 F. Supp. 1143 (1969) (Docket

No. 31). Involves alleged violations of lottery statute and

method of investigation to discover evidence through the

use of electronic device. Judgment of the three-judge

District Court that no First Amendment rights were vio

lated was affirmed, citing Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U.S. 117,

and Perez v. Ledesma, 91 S. Ct. 674.

(3) McGrew v. City of Jackson, 307 F. Supj). 751; llosey

v. City of Jackson, 309 F. Supp. 527 (Docket Nos. 116, 134).

Involve constitutionality of the obscenity statutes. The

judgments of three-judge Federal District Court panel in

favor of the City of Jackson were vacated and the cases

remanded to the District Court for reconsideration in the

light of Younger, Samuels, and Fernandes, supra.

(4) Porter v. Kimsey, 309 F. Supp. 993 (Docket No. 5462).

Involves challenge to constitutionality of Georgia defama

tion statute. The judgment of the three-judge District Court

was affirmed in the light of Younger, Samuels, and Fernan

dez, supra. The three-judge District Court had held that

where prosecution under the criminal defamation statute

affected plaintiff alone and not a group seeking to exercise

some broad right of freedom of speech and arrest, was based

19

upon a private warrant taken out by one citizen of a state

against another, and was not founded on organized effort

of law enforcement or harassment by public officials, action

to enjoin the indictment or prosecution did not lie and the

motion to dismiss was granted.

(5) Embry v. Allen, reported as Hunter v. Allen, 286 F.

Supp. 830 422 F. 2d 1158 (Docket No. 5539), and cited in

our Initial Brief at pp. 43, 44. Challenge to the constitution

ality of fourteen sub-sections of the disorderly conduct

ordinance of the City of Atlanta, Georgia as being so vague

and overbroad on their face as to violate the First Amend

ment of the U. S. Constitution. Judgment below was partly

for the City of Atlanta. As in the case at bar civil rights

of a class of persons were involved. The U. S. Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that certain of the chal

lenged sections were constitutional and certiorari was then

petitioned. The TJ. S. Supreme Court granted the petition

for a writ of certiorari and the judgment of the U. S. Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit was reverved in the light

of Younger, Samuels and Fernadez, supra.

(6) Geiger v. Jenkins, 316 F. Supp. 370 (Docket No. 5952).

Action by physician seeking injunction against enforcement

of a Georgia statute regulating revocation of licenses to

practice medicine. The three-judge Federal District Court

dismissed the complaint, and held that federal interference

with state criminal proceedings was prohibited by the anti

injunction statute (Sec. 2283 of the Judicial Code). The

TJ. S. Supreme Court affirmed the judgment in the light of

Younger, et al., supra.

B. Cases In Other Circuits Applying The

Abstention Doctrine.

A number of the additional U. S. Supreme Court decisions

on March 29, 1971 from cases arising from other circuits,

also applied the “ Abstention Doctrine.”

(1) Wheeler v. Goodman, 306 F. Supp. 58 (Docket No.

102). Challenge to constitutionality of vagrancy statute of

20

North. Carolina. The three-judge District Court held the

vagrancy statute in violation of the 14th Amendment to the

U. S. Constitution because it was. vague and overbroad,

punished mere status, and invidiously discriminated against

those without property. Injunction was granted. The U. S.

Supreme Court vacated the judgment and remanded the

matter to the U. S. District Court for the Western District

of North Carolina (Charlotte Div.) in the light of Younger,

supra.

(2) Demich, Inc. v. Per don, 426 F. 2d 643 (Docket No.

500). Challenge to constitutionality of obscenity statute.

Decision by three-judge Circuit Court (9th Circuit). The

Federal District Court had denied injunctions against

criminal prosecution but directed return of seized film with

out prior adversary hearing and appeals were taken. The

Circuit Court affirmed order for return of film and remanded

case with instructions to vacate injunction against future

seizures. Certiorari was granted. The judgment was va

cated and the case remanded to the U. S. Circuit Court of

Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in light of Peres, supra.

(3) ABC Boohs, Inc. v. Benson, 315 F. Supp. 695 (Docket

No. 844). Challenged consitutionality of Tennessee obscen

ity statute. Three-judge District Court held not unconstitu

tional on its face. U. S. Supreme Court vacated and re

manded.

(4) Rollins v. Shannon, 292 F. Supp. 580 (Docket No.

5013). Challenged constitutionality of unlawful assembly

ordinance of St. Louis, Missouri. Injunction sought. Three-

judge District Court found arrests made in good faith and

not motivated by any attempt to silence speech and as

sembly, and further that the statute was not void for

“ vagueness” or “ over-breadth.” Injunction relief was

denied. The TJ. S. Supreme Court vacated the judgment and

remanded the case to the IT. S. District Court for the Eastern

District of Missouri (Eighth Circuit) for reconsideration in

light of Younger, Samuels, Fernandez and Boyle, supra.

21

This case involved claims of racial discrimination, bad

faith, harrassment, vagueness, over-breadth, great and im

mediate irreparable injury, and is similar to the claims of

Appellants in the case at bar,

(5) Brown v. Fallis, 311 F. Supp, 548 (Docket No. 5412).

Challenge to constitutionality of Oklahoma obscenity stat

ute based on allegation of vagueness and over-breadth.

Three-judge District Court dismissed action on ground

proof failed to show those special circumstances where

state criminal prosecutions may be interfered with. Judg

ment was affirmed by the TJ. S. Supreme Court on the basis

of Younger, supra.

C. Other Developments.

(1) North v. Greene, Dist. Ct. No. 413-71, March 18, 1971

Opinion per curiam. District of Columbia.

Challenge to Constitutionality of Criminal Procedure

Act. Juvenile delinquency. Injunction against proceedings

sought. Held that U. S. District Courts are not to employ

equity powers to interfere with criminal proceedings pend

ing in other judicial systems such as the D. C. Superior

Court when constitutional claims may be raised and adjudi

cated in such proceeding, citing Younger v. Harris, supra.

(2) Ohio v. Wyandotte Chemicals Corporation, 39 L.W.

4323, March 23, 1971.

This case involves original jurisdiction by the IJ. S. Su

preme Court in motion by the State of Ohio for leave to

file complaint under the environmental law. Despite orig

inal jurisdiction conferred by the Constitution, the Supreme

Court declined to exercise same and denied the motion on

the ground that the issues were bottomed on local law, that

the Ohio courts are competent to consider such laws, that

several national and international bodies are actively con

cerned with the pollution problems involved here, and that

the nature of the case requires the resolution of complex,

novel and technical factual questions that do not implicate

22

important problems of federal law, which are the primary

responsibility of the Supreme Court.

We cite this matter as the ultimate in the development

of the “ Abstention Doctrine” and the broadening trend in

its application. This is but another of a growing number

of examples of “ Federalism.”

CONCLUSION

For the reasons given above, Defendants-Appellees

Mobile, et al. pray that this Court upon rehearing vacate

the majority opinion of the three-judge panel of this Court

involving the constitutionality of Mobile, Alabama Code

§§14-7, 14-11, 14-13 and 14-051 et seq. and dismiss the

complaint.

Respectfully submitted,

F red G-. C ollins , City Attorney

City of Mobile

P. 0. Box 4492

Mobile, Alabama 36601

W illiam H. B righam

P. 0. Box 164

Mobile, Alabama 36601

C harles S. R h y n e

B rice W. R h y n e

A lfred J. T ig h e , Jr.

R i-iy n e & R h y n e

400 Hill Building

839—17th Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20006