Brooks v. Allain Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

November 3, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Brooks v. Allain Jurisdictional Statement, 1984. 9e4958ec-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6e5dc871-b7ae-4f9a-81d1-a41cf0d33bd1/brooks-v-allain-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

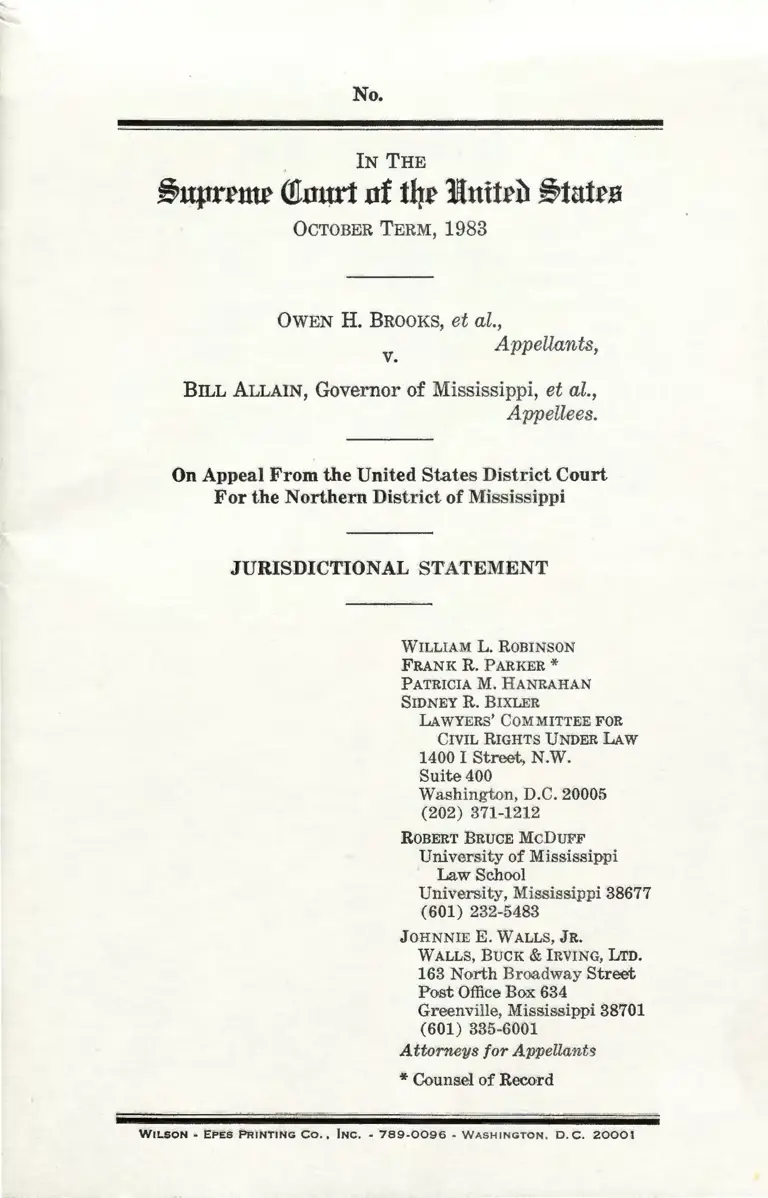

No.

IN THE

~uprtutt Ointlrt nf tqr lltuittb ~tatra

OCTOBER TERM, 1983

OWEN H. BROOKS, et al.,

v. Appellants,

BILL ALLAIN, Governor of Mississippi, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Mississippi

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

FRANK R. PARKER -x

pATRICIA M. HANRAHAN

SIDNEY R. BIXLER

LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

1400 I Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202 ) 371-1212

ROBERT BRUCE McDUFF

University of Mississippi

Law School

Univers,ity, Mississippi 38677

(601) 232-5483

JOHNNIE E. WALLS, JR.

WALLS, BUCK & IRVING, LTD.

163 North Broadway Street

Post Office Bo·x 634

Greenville, Mississippi 38701

(601) 335-6001

Attorneys for Appellants

* Counsel of Record

WILSON· EPES PRINTING Co., INC . • 789-0096 ·WASHINGTON, D . C . 20001

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether, given an extensive past history of racial

discrimination against black voters of Mississippi in

voting and congressional redistricting, the District Court

was prohibited by law from creating a 65 percent black

congressional district in which black voters have an op~

portunity to gain representation of their choice as a rem~

edy for a court~ordered plan found to deny black voters

an opportunity to gain representation of their choice.

2. Whether the District Court's remedial plan violates

the strict guidelines against racial dilution applicable to

court~ordered plans and provides an effective remedy for

voting rights violations by creating a large, sprawling,

uncompact district which splits off adjoining black pop~.

ulation concentrations.

(i)

ii

PARTIES

Plaintiffs below are: Owen H. Brooks, Rev. Harold R.

Mayberry, Willie Long, Robert E. Young, Thomas Mor

ris, Charles McLaurin, Samuel McCray, Robert L. Jack

son, Rev. Carl Brown, June E. Johnson, and Lee Ethel

Henry.

Appellees (defendants below) are: Bill Allain, Gover-'

nor of Mississippi, Edwin Lloyd Pittman, Attorney Gen

eral, Dick Molpus, Secretary of State, in their offiCial

capacities and as members of the Mississippi State Board

of Election Commissioners (substituting the successors in

office for the original defendants), and the Democratic

and Republican State Executive Committees.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

OPINIONS BELOW --·---·-----------------------·---- -------------------- ---- 2

JURISDICTION --------------·-------·-------- ----•-- --·------- -------------------- 2

STATUTORY PROVISION INVOLVED--·------------------- 2

STATEMENT OF THE GASE ----------- --------- -- -------- ---------- 3

'J'HE QUESTIONS ARE SUBSTANTIAL ----------------- ---- 11

I. THE DISTRICT' COURT MISCONSTRUED

GOVERNING LEGAL REMEDIAL PRINCI

PLES WHEN IT HELD THAT WAS PRO

HIBITED BY LAW F ROM ESTABLISHING

A REMEDIAL DISTRICT WHICH WOULD

GIVE BLACK VOTERS AN OPPORTUNITY

TO ELECT CANDIDATES OF THEIR

CHOICE ---·----------------·--- ----- ----·--------------------·------------·---- 13

II. THE DISTRICT COURT'S PLAN VIOLATES.

THE STRICT GUIDELINES ESTABLISHED

FOR COURT-ORDERED PLANS BY THIS

COURT IN CONNOR v. FINCH -------------------- ---- 18

CONCLUSION ·----------------------------------- --------------------------------- 20

APPENDICES

Appendix A. District Gourt Opinion ---- ------ ---------- 1a

Appendix B. District Court Judgment__________ __ _____ _ 22a

Appendix G. Notice of Appeal --------------------- ----------· 31a

(iii)

J

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORIT'IES

Cases Page

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977) ___ __________ _____ _ 11, 18-20

Connor v. Johnson, 279 F. Supp. 619 (S.D. Miss ..

. 1966) (three-judge court), afj'd mem., 386 U.S.

483 (1967) ---------------------------------------------------- ------ ------ 4

Connor v. Johnson, 402 U.S. 690 (1971) __________________ 18

Donnell v. United States, Civil No. 78-0392 (D.D.C.

July 31, 1979) (three-judge court), aff'd mem.,

444 u.s.. 1059 (1980) --------------- ---·-- -------------------- -- ---- 9

East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424

u.s. 636 (1976) ------------ ------ ---------- --------------------- ----- 12, 18

Jones v. City of Lubbock,-- F.2d- (5.th Gir.

1984) ·--------·------------·-- ----------·----------------·------------------------ 12

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County,

544 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.) (en bane), cert. denied,

434 u.s. 968 (1977) --- ----------------------- ---------------------- 19

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D.La. 1983)

(three-judge court) ·------------·-------- -- -- ------------------------ 12

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981) ________ ______ 12

Mississippi v. Smith, 541 F. Supp. 1329 (D.D.C.

1982) (three-judge court), appeal dism'd, 103

S.Ct. 1888 (1983) --- ----- -------------------------- -- --------------- 4, 5

Mississippi v. United States, 490 F. Supp. 569

(D.D.C. 1979) (three-judge court), aff'd mem.,

444 u.s .. 1050 (1980) ·---------------------------------------------- 9

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982.) ______________ _______ _ 12, 19

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa-

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) -------------------- --- ------------------- 13

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S..

144 (1977) ----------·----·----·---------------------------------- ----------1, 12, 15

United States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965) __ 4

Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S. 37 (1982) _____________________ 12

Valesquez v. City of Abilene,-- F.2d- (5th

Cir. 1984) ·------------- ---------------------------------------------------- 12

White v. Regester, 412' U.S. 755 (1973) ___________________ 14

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1972.) __________ ______ ______ 12

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S.. 535 (1978) --- -- --- ---------- -- 12

Other Authorities

S. Rep. No. 9·7-417, 9·7th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982) ____ 14,19

IN THE

:§uprl'ml' Qlnurt nf t~l' 1llttitt>~ §tatrn

OCTOBER TERM, 1983

No.-

OWEN H. BROOKS, et al.,

v. Appellants,

BILL ALLAIN, Governor of Mississippi, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Mississippi

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants, black registered voters of Mississippi who

reside in the Mississippi Delta area, appeal from the

final judgment of the United States District Court for

the Northern District of Mississippi, entered January 6,

1984, ordering into effect a new court-ordered congres

sional redistricting plan. While appellants agree with

the District Court's holding that the pre-existing 1982

court-ordered plan violates Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, they challenge the District Court's design of

a new court-ordered plan, contending in this appeal that

the new plan does not meet this Court's guidelines for

court-ordered redistricting plans, that it follows from a

misapplication of Section 2's language regarding propor

tional representation, that it misconstrues this Court's

holding in United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430

U.S. 144 ( 1977), and that it fails to remedy the Section

2

2 violation as well as a previous Section 5 violation

found by the Attorney General relating to congressional

districting in Mississippi.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the three-judge District Court for the

Northern District of Mississippi entered April 16, 1984,

is unreported and is reproduced in Appendix A. The

prior District Court opinion is reported at 541 F. Supp.

1135 (N.D. Miss. 1982) (three-judge court), and was

vacated and remanded by this Court for reconsideration

in light of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as

amended in 1982, 103 S.Ct. 2077 ( 1983).

The District Court opinion in~ related case, Mississippi

v. Smith, is reported at 541 F. Supp. 1329 (D.D.C.

1982) (three-judge court), appeal dism'd, 103 S.Ct. 1888

(1983).

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the three-judge District Court or

dering into effect a new court-ordered congressional re

districting plan was entered on January 6, 1984, and is

reproduced herein as Appendix B. Appellants filed their

notice of appeal on February 15, 1984, reproduced as

Appendix C, within 60 days of the date of entry of the

final judgment as provided by 28 U.S.C. § 2101 (b). By

Order dated April 4, 1984, Justice White extended the

time for docketing this appeal to and including May 15,

1984.

This Court's jurisdiction is invoked pursuant to 28

u.s.c. § 1253.

STATUTORY PROVISION INVOLVED

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973, as amended in 1982, Pub. L. No. 97-205, § 3, 96

Stat. 134, provides:

3

Sec. 2 (a) No voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any state or political subdivi

sion in a manner which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the

United States to vote on account of race or color, or

in contravention of the guarantees set forth in sec

tion 4 (f) (2), as provided in subsection (b).

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established

if, based on the totality of circumstances, it is shown

that the political processes leading to nomination or

election in the State or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by members of a class

of citizens protected by subsection (a) in that its

members have less opportunity than other members

of the electorate to participate in the political proc

ess and to elect representatives of their choice. The

extent to which members of a protected class have

been elected to office in the State or political sub

division is one circumstance which may be consid

ered: Provided, that nothing in this section estab

lishes a right to have members of a protected class

elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the

population.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

For the past eighteen years, since 1966, black voters

of Mississippi have been subjected to racial discrimina

tion in congressional redistricting and denied an equal

opportunity to elect candidates of their choice in con

gressional elections.

Mississippi is 35 percent black, and blacks are most

heavily concentrated in the Delta area, in northwest Mis

sissippi. Prior to the· passage of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, Mississippi had a Delta congressional district

which was 65.51 percent black/ but blacks we·re almost

1 The old Delta district, which was then the Third Congressional

District, was 65.51 percent black in population under the 1956 plan

in 1960. In 1962 the Second and Third Districts were combined,

totally excluded from the electoral process by the State's

"long-standing, carefully prepared, and faithfully ob

served plan to bar Negroes from voting ... " United

States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128, 135-36 (1965). In

1966, just as black citizens were beginning to register

and vote in substantial numbers, the Mississippi Legisla

ture redrew the boundaries of the State's five congres

sional districts and divided the heavily-black Delta area

horizontally among three congressional districts, . depriv

ing black voters of a voting majority in any of the dis

tricts. See Mississippi v. Smith, 541 F. Supp. 1329, 1331

(D.D.C. 1982) (three-judge court), appeal dism'd, 103

S.Gt. 1888 (1983) .2 Although a District Court rejected

a constitutional challenge to the 1966 plan/ that plan

never received the Federal preclearance required by Sec

tion 5 of the Voting Rights Act. ld. This same pattern

of dividing up the black population concentration of the

Delta area and depriving black voters of a majority

black congressional district was followed in the 1972 and

1981 redistrictings enacted by the Mississippi Legisla

ture. Id.

In March, 1982, the Attorney General of the United

States objected pursuant to Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act to Mississippi's 1981 congressional redistrict

ing plan (the "least change" plan) for unlawful frag

mentation and dilution of black voting strength in the

Delta area.4 Although the Mississippi Legislature was

and the black population percentage was reduced to 59.29 percent.

Ex. P-13A.

2 The history of Mississippi congressional redistricting was ex

tensively discussed in our prio,r Jurisdictional Statement in Brooks

v. Winter, No. 82-233, pp. 16-23.

s Connor v. Johnson, 279 F . Supp. 619 (S.D. Miss. 1966) (three

judge court) (newspaper articles showing racial motivation may

not be used to impeach "the solemn acts of the Congress or o.f

State legislatures"), aff'd mem., 386 U.S. 483 (1967).

4 In his Section 5 objection letter, the Attorney General found

that prior to the enactment of the Voting Rights Act, · Mississippi

5

then in session when the Attorney General's Section 5

objection was announced, and has held two regular ses

sions since then, no new legislative congressional redis

tricting plan has been enacted by the Mississippi Legis

lature.5

Appellants Owen H. Brooks, et al., filed this class ac

tion in April, 1982, seeking a court-ordered plan for the

conduct of congressional elections. After a trial, the

three-judge District Court in June, 1982 enjoined use of

the "least change" plan based on the Section 5 objection

and enjoined use of the then-existing 1972 plan for un

constitutional malapportionment. Jordan v. Winter, 541

F. Supp. 1135 (N.D. Miss. 1982) (three-judge court),

vacated and remanded sub nom. Brooks v. Winter, 103

S.Ct. 2077 (1983).

Appellants urged the District Court to order into ef

fect one or the other of two plans (the "Kirksey plans")

which kept the Delta area intact within one congres

sional district and combined the Delta area with ad

joining, predominantly black portions of Hinds County

and the· City of Jackson (which is located within Hinds _

County), resulting in plans ·which each had one majority

black congressional district which were 64.37 percent

black and 65.81 percent black, respectively. 541 F. Supp.

at 1140. Instead, the District Court ordered into effect a

had one congressional district in the Mississippi Delta a.rea which

was 65 percent black. The Mississippi Legisla,turels 1981 plan, he

found, contained districts which "ha.v.e been drawn horizontally

across the majority"black Delta area in such a, manne'r as, to dis

member the black population concentration and effectively dilute

its voting strength." See Brooks v. Winter, No•. 82-233, Jurisdic

tional Statement, Appendix B, pp. 25a-29a.

5 Mississippi filed a judicial preclearance action in the Dis,trict

Court for the District of Columbia for app·roval o.f its 1981 plan, but

that action was voluntarily dismissed by the State after the District

Court denied the State's motion for summary judgment. Mississippi

v. Smith, 541 F. Supp. 1329 (D.D.G. 1982.) (three-judge court),

appeal dism'd, 103 S.Ct. 1888 (1983).

6

plan (the "Simpson plan") which combined the Delta

area with six predominantly-white Hill counties in east

central Mississippi, resulting in four majority white dis

tricts and one district (the Second District) which had a

slight black population majority of 53.77 percent ( id. at

1139) but which had a white voting age population ma

jority (black voting age population of 48.05 percent)

(District Court Opinion of April 16, 1984, App. A at-

tached, p. 5a). In the 1982 congressional elections

in the Second District a black candidate, veteran state

legislator Robert Clark, won the Democratic primary

but lost the general election to a white opponent, the

District Court in its most recent opinion found, in part

because of racial bloc voting by whites and racial cam

paigning by the white candidate which induced racially

polarized voting. App. A, pp. 10a-12a.

The black voter plaintiffs appealed, contending that

the District Court's 1982 court-ordered plan unneces

sarily diluted black voting strength in the face of alter~

native, more compact plans which would have preserved

the Delta area intact and would have avoided combining

the Delta area with predominantly white Hill counties to

diminish black voting strength. The state official defend

ants also appealed, contending that the District Court

erred in implementing a court-ordered plan. This Court

in May, 1983 vacated and remanded the District Court's

decision "for further consideration in light of Section 2

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. Section 1973,

as amended in 1982." Brooks v. Winter, 103 S.Ct. 2077

(1983).

On remand, after a two-and-a-half-day trial in De

cember, 1983, the District Court ruled that in the struc

ture of the Second Congressional District its 1982 court

ordered plan unlawfully diluted black voting strength in

violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as

amended in 1982:

7

The combination of six predominantly white eastern

counties with the Delta region's black population,

when considered in light of the effects of past dis

crimination on black efforts to participate in politi

cal affairs and the existence of racially polarized

voting, operated to minimize, cancel, or dilute black

voting strength in the Second District.

App. A, p. lla. On the facts presented at trial, the Dis

trict Court found that black voters in the Delta area,

under the new Section 2 standard, have less opportunity

than their white counterparts to participate in the politi

cal process and to elect representatives of their choice.

The court found that Mississippi has a long history of

official racial discrimination in voting which "includes

the use of such discriminatory devices as poll taxes,

literacy tests, residency requirements, white primaries,

and the use of violence to intimidate blacks from regis

tering for the vote." App. A, p. 9a. The effects of this

past discrimination, the court found, "presently impede

black voter registration and turnout. Black registration

in the Delta area is still disproportionately lower than

white registration. No black has been elected to Con

gress since the Reconstruction period, and none has been

elected to statewide office in this century." ld. The court

also found that black political participation in the Delta

area is impeded by facts showing that blacks in the

Delta area have disproportionately lower median family

income ($7,447 for blacks, as compared with $17,467 for

whites), less education (more than half have less than

nine years of education, while the majority of whites are

high school graduates), unemployment rates which are

two to three times higher than the white unemployment

rate, and inferior housing conditions. Id., p. lOa.

Equal black political participation in Mississippi elec

tions, the District Court determined, also is impeded by

racial bloc voting, which deprives black voters of an

equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice in

a district in which they do not have a voting majority:

Plaintiffs' proof, also based on analysis of these elec

tion returns, demonstrated a consistently high de

gree of racially polarized voting in the 1982 elec

tion and previous elections. From all of the evi

dence, we conclude that blacks consistently lose elec

tions in Mississippi because the majority of voters

choose their preferred candidates on the basis of race.

We therefore find racial bloc voting operates to di

lute black voting strength in Congressional districts

where blacks constitute a minority of the voting age

population. Since the Second District under the

Simpson Plan does not have a majority black voting

age population, the presence of racial bloc voting in

that district inhibits black voters from participating

on an equal basis with white voters in electing rep

resentatives of their choice.

ld., pp. lOa-lla.

At the second trial plaintiffs urged, on the basis of

this factual proof showing that black voters in Mississippi

are seriously disadvantaged politically, that a district

which is 65 percent black in population or 60 percent

black in voting age population was necessary as a rem

edy to give black voters an equal opportunity to partici

pate in the political processes and to elect candidates of

their choice. The State of Mississippi has stipulated that

because of low black voter registration, turnout, and

racial bloc voting, absent exceptional circumstances, "a

district should contain a black population of at least 65

percent or a black V AP of 60 percent to provide black

voters with an opportunity to elect a candidate of their

choice." '6 Similar findings have been made by District

6 This stipulation, which was entered into in Mississippi v. Smith,

and which was admitted in evidence in this case (Ex. P-1, p. 5,

n 16)' establishes:

16. Low black voter registration and voter turn-out combined

with racial bloc voting make it necessary for an electoral dis

trict in Mississippi to contain a substantial majority of black

eligible voters in order to provide black voters with an oppor-

9

Courts in reviewing Mississippi redistricting plans un

der Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Mississippi v.

United States, 490 F. Supp. 569, 575 (D.D.C. 1979)

(three-judge court), aff'd mem., 444 U.S. 1050 (1980);

Donnell v. United States, Civil No. 78-0392 (D.D.C. July

31, 1979) (three-judge court), aff'd mem., 444 U.S. 1059

( 1980). The expert witness testimony adduced at the

second trial from Dr. Gordon Henderson, professor of

political science at Earlham College and an experienced

Mississippi election analyst, and State Senator Henry

Kirksey, also an experienced redistricting expert, sup

ports this conclusion (Trial Transcript, Dec. 19-21, 1983,

pp. 129, 173-74), as does testimony from seven black

political and community leaders from Delta counties.7

tunity to elect a candidate of their choice. It has been gen

erally conceded that, barring exceptional circumstances such as

two candidates splitting the vote, a district should contain a

black population of at least 65 percent or a black VAP of 60

percent to provide black voters with an opportunity to elect a

candidate of their choice. In more recent elections black candi

dates have, on occasion, been elected to. public office from dis

tricts with a population less than 65 percent black.

7 Ex. P-22, Dr. Robert E. Young, Washington County, p. 65 (dis

trict should be 65 percent black or more so that black people could

"overcome this historical feeling of hopelessness or disbelief that

they can really make a difference") ; Ex. P-23, Gregory Flippins,

Bolivar County, fo·rmer mayor, p. 25 (district would have to. be

60 percent or· 65 percent black in voting age population) ; Ex.

P-24, Attorney Thomas Morris, Bolivar County, pp. 10-11 (dis

trict would have to be 65 percent black in popula.tion because of

"past discrimination in the voting process and in the past attempts

to disenfranchise blacks") ; Ex. P-25, Samuel McCray, community

organizer, Quitman County, p. 67 (district would have to be 65 perr

cent black for black voters to have "a fair chance of electing a

person of [their] choice") ; Ex. P-27, Jake Ayers, Mississippi Free~

dom Democratic Party community organizer, Washington County,

pp. 20-21 (district would have to be at least 58 percent black in

voting age• population in order for blacks to have an equal oppor

tunity to elect candidates of their choice) ; Ex. P-28, Clarence Hall,

Issaquena County, p. 9 (district would have to be 60 percent black

in voting age population) ; Ex. P-30, Attorney Edward Blackmon,

presently, member of the Mississippi House of Representatives•,

Madison County (district must be 68 percent to 70 percent black).

10

At the second trial, plaintiffs offered two additional,

geographically-compact congressional redistricting plans

based on existing voting precincts. One contained a ma

jority black district in the Delta area which was 64.35

percent black in population (Ex. P-81) and another con

tained a majority black district in the Delta area which

was 63.60 percent black in population (Ex. P-82). Both

plans, Senator Kirksey testified, would give black voters

a reasonable opportunity to elect candidates of their choice

in the one majority black district ( Tr. 166-67, 17 4).

The District Court rejected plaintiffs' proposed reme

dial plans for the express reason that these plans "would

probably insure the election of a black congressman in

the Second District" (App. A, p. 15a). This factor, the

District Court held, was inconsistent with the disclaimer

in Section 2, as amended (App. A, pp. 14a-15a), which

provides that "nothing in this section establishes a right

to have members of a protected class elected in numbers

equal to their proportion in the population."

The court rejected alternative plans offered by plain

tiffs which would achieve a significantly higher black

voting age population (approximately 60%) in the

Second District. Plaintiffs argue that a black voting

age population of such preponderance is required

for blacks to elect representatives of their choice.

Amended § 2, however, does not guarantee or insure

desired results, and it goes no further than to af

ford black citizens an equal opportunity to partici

pate in the political process.

App. A, p. 14a. The court stated that its own plan "sat

isfies the requirements of amended § 2 without achieving

proportional representation for blacks in Mississippi"

( id.). The District Court also gave as reasons for re

jecting plaintiffs' plans that they would reduce the black

population percentage in the Fourth District to the 33

percent level (from 41.99 percent in the court's plan)

(App. A, p. 14a), and would combine urban areas of

the City of Jackson with the rural Delta area ( id.).

11

For the 1984 congressional election, the District Court

devised a new plan which, in the Second District, elimi

nated five of the six predominantly-white Hill counties,

and which extended further south to take in two majority

black River counties and portions of the Jackson sub

urbs in Hinds County. These changes increased the

black population percentage of the Second District to 58.30

percent from 53.77 percent, and increased the black vot

ing age population percentage to 52.83 percent from

48.05 percent (App. A, p. 13a). The District Court ac

knowledged, however, that its new plan "does not pro

vide a compact geographical configuration for the Second

District" ( id., p. 15a).

THE QUESTIONS ARE SUBSTANTIAL

This case presents the . important issues surrounding

the scope and application of a District Court's remedial

authority when designing a court-ordered redistricting

plan in the wake of a violation of Section 2 of the Vot

ing Rights Act.

With the new amendment to Section 2 taking effect in

the summer of 1982, this Court has yet to consider the

proper remedial response to a Section 2 violation where

the legislature abandons its duty to fashion a lawful

plan. Indeed, this Court has never fully explicated the

remedial parameters involved after a finding of vote

dilution in a constitutional case, although several decisions

have skirted the edges of the issue. 8

8 Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977), is probably the closest.

The lower court designed a legislative redistricting plan after the

Attorney General objected to the legislature's. plan under Section 5.

Plaintiff's appeal to this Court contended that the lower court

ordered plan was malapportioned and, in addition, diluted black

voting strength. This Court reversed on the malappo·rtionment

issue, without ruling on the dilution claims, but prescribed guide;.

12

Lower courts all over the South are hearing cases in

volving the 1982 amendment to Section 2 in all of its

aspects, including the question of remedial relief. See

e.g., Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983)

(three judge court); Valesquez v. City of Abilene, -

F.2d -- (5th Cir. 1984); Jones v. City of Lubbock,

--F.2d -- (5th Cir. 1984). Guidance from this

Court would be of great help.

While appellants challenge the District Court's reme

dial order in part on the basis of factual considerations

relevant to congressional redistricting in the State of Mis

sissippi, they also raise broader issues of the proper

standards for a court-ordered redistricting plan, the cor

rect construction of Section 2's proportional representa

tion disclaimer, and the application of this Court's deci

sion in United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S.

144 (1977).

lines. so that the district court could avoid dilution problems upon

remand. 431 U.S. at 421-426.

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1972), involved a malapportion

ment case and did not p·resent any dilution questions. East Carroll

Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976), was a dilu

tion case, but the issues before this Court went only to· whether the

remedial plan was court-ordered or not, and whether court-ordered

plans for local governments must have single-member districts.

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978), was limited to the distinc

tion between a court-ordered and a legisla.tive plan, as was Mc

Daniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981). Upham v. Seamon, 456

U.S. 37 (1982) dealt with the District Court's remedial power after

a Section 5 objection by the Attorney General, in the absence of a

constitutio·nal adjudication of vote dilution. Rogers v. Lodge, 458

U.S. 613, 627-628 (1982), devo·ted only a paragraph to the remedial

issue, merely holding that the District Court and Court of Appeals

had found no facto·rs to militate against the use of single-member

districts after an at-large system had been ruled unconstitutional.

13

I. THE DISTRICT COURT MISCONSTRUED GOV

ERNING LEGAL REME.DIAL PRINCIPLES WHEN

IT HELD THAT IT WAS PROHIBITED BY LAW

FROM ESTABLISHING A REMEDIAL DISTRICT

WHICH WOULD GIVE BLACK VOT'ERS AN OP

PORTUNITY TO ELECT CANDIDATES OF THEIR

CHOICE.

The issue in this case is not whether plaintiffs' rights

have been violated in congressional redistricting-all par

ties now concede that there was a violation-but rather

what remedy should the District Court fashion to make

the victims of discrimination whole. The District Court

determined that its own prior plan violated amended

Section 2 by denying black voters in the Delta area an

equal opportunity to participate in the political processes

and to elect candidates of their choice. Given the equi

table remedial principle that the remedy should be de

termined by the nature and scope of the violation, Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S~

1 (1971), it follows that black voters of Mississippi who

have been discriminated against in congressional redis

tricting for the past eighteen years should now be given

an opportunity to gain representation of their choice in

one congressional district.

The District Court erred in holding that it was pro

hibited by law from fashioning a plan containing one

district with a sufficiently large black voting age popula

tion majority as to give black voters an opportunity to

elect representatives of their choice. First, the District

Court clearly was wrong when 'it ruled that creating one

65 percent black district would constitute proportional

representation. The overwhelming testimony was that

even creating a 65 percent black district would not guar

antee the election of a black member of Congress. N ev

ertheless, black people comprise 35 percent of the state's

population and 31 percent of the state's voting age pop

ulation. Providing black voters with an opportunity to

14

elect one out of five members of Congress (20 percent)

does not constitute proportional representation in any

sense.

Second, the District Court disregarded the statutory

language of the 1982 amendment to Section 2 and its

legislative history when it ruled that Section 2 prohibits

the creation of a 65 percent black district as a remedy

for proven racial discrimination in redistricting. Sec

tion 2's disclaimer against a right to proportional rep

resentation clearly is addressed to the issue of what con

stitutes a violation of Section 2, not to the design of a

remedy. Section 2 (b) begins: "A violation of subsection

(a) is established if ... " The extent to which minority

officeholders have been elected "is one circumstance which

may be considered : Provided, That nothing in this sec

tion establishes a right to have members of a protected

class elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the

population." This entire subsection addresses only what

constitutes a violation, and does not control the issue of

a remedy. No protected group has a right to proportional

representation, therefore the lack of proportional repre

sentation does not, in and of itself, constitute a violation

of Section 2.

This disclaimer is directly derived from this Court's

decision in White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 ( 1973), in

which the Court held:

To sustain such claims [that multimember districts

are being used invidiously to cancel out or minimiz~

minority voting strength], it is not enough that the

racial group allegedly discriminated against has not

had legislative seats in proportion to its voting po

tential.

412 U.S. at 765-66. See S. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. 28, 31-32 (1982). Congress did not intend by

this disclaimer to limit the options available to District

Courts in considering a remedy:

15

The court should exercise its traditional equitable

powers to fashion the relief so that it completely

remedies the prior dilution of minority voting

strength and fully provides equal opportunity for

minority citizens to participate and to elect candi

dates of their choice.

Id. at 31 (footnote omitted).

In this case the District Court, having struck down

its own prior plan for failing to provide black voters

with an opportunity to elect candidates of their choice,

failed to exercise "its traditional equitable powers" to

"completely remedy" this dilution of black voting strength

by failing fully to provide "equal opportunity for minor

ity citizens to participate and to elect candidates of their

choice." In fact, the trial court rejected plaintiffs' pro

posed plans for the explicit reason that would "probably

insure the election of a black congressman."

This determination has very serious implications for

the large group of voting rights cases currently being

litigated under Section 2. If black voters in Section 2

cases are deprived of remedies commensurate with the

scope of the violation (discriminatory denial to minority

voters of the opportunity "to elect representatives of

their choice") , the recently-enacted amendment to Sec

tion 2 which was designed by Congress to provide minor

ity voters with a new statutory framework for overcom~

ing racial discrimination in voting could well be rendered

nugatory.

The District Court also disregarded this Court's deci

sion in United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S.

144 ( 1977), when it condemned plaintiffs' efforts to

create a 65 percent black district as "an obvious racial

gerrymander" (App. A, p. 14a). In that case the issue

was whether the New York Legislature was constitu

tionally prohibited from creating 65 percent black state

legislative districts to meet the requirements of Section

5 of the Voting Rights Act, and the Court determined

16

that there was no constitutional violation. The Court

determined that the constitution did not prohibit race

conscious remedies for dilution of minority voting strength

"to attempt to prevent racial minorities from being re

peatedly outvoted by creating districts that will afford

fair representation to the members of those racial groups

who are sufficiently numerous and whose residential pat

terns afford the opportunity of creating districts in which

they will be in the majority." 430 U.S. at 168 (plurality

opinion of White, J.)

Here the District Court's own findings demonstrate

that merely creating a razor-thin 52.83 percent black

voting age population majority is not sufficient to "afford

fair representation" to discriminated-against black Mis

sissippi voters. The District Court found that the effects

of past discrimination continue to impede electoral par

ticipation by black voters in Mississippi. Because of this

past discrimination, and continued disparities in income,

education and other socio-economic measures which de

press minority political participation, black voter regis

tration and turnout are still disproportionately lower than

white registration and turnout. Black voters also are

deprived of opportunities to gain fair representation in

districts in which they lack a substantial voting majority

by a "consistently high degree of racially polarized vot

ing" by white voters. The overwhelming weight of the

proof and testimony in this case is that this 52.83 per

cent voting age population majority is simply not enough

to enable black voters to overcome these enormous and

continuing barriers to equal black political participation

in the Delta area. To the extent that the District Court

may have thought otherwise (App. A, pp. 13a-14a), those

findings are contrary to the overwhelming weight of the

evidence and are clearly erroneous.9

9 For the defendants, Dr. Thomas Hofeller stated that a razor

thin black V AP majority of 50.13% in the Second District was

sufficient to insure black voters equal access to the political process.

17

The other reasons given by the District Court for re

jecting plaintiffs' plans also should be rejected. Com

bining the heavily-black Delta counties with predomi

nantly-black areas of the City of Jackson should not con

stitute a serious obstacle to giving black voters an op

portunity for representation of their choice. All of the

districts, to some extent, combine urban and rural areas.

The Fifth District combines the urban Gulf Coast area

with extremely rural and sparsely-populated areas of

south Mississippi, and the chairman of the Mississippi

Legislature's Joint Congressional Redistricting Commit

tee testified that this was unavoidable and not inconsist

ent with state policy in congressional redistricting ( 1982

Trial Transcript, p. 243). In addition, any increase in

black voting strength in the Second District must neces

sarily decrease the percentage of blacks in some adjoining

district. This does not constitute a prohibited dilution of

black voting strength where the adjoining district does

not contain a black voting majority. There was literally

no evidence presented at trial that a decrease in the black

population percentage in the Fourth District by eight per

centage points would necessarily make the Fourth District

Representative insensitive to minority needs (App. A, p.

14a).

Tr. at 410, 454. However, he conceded that his figures did not take

into account the conditions of lower black voter registration, lower

black turnout, and lesser financial resources for black candidates

which pervade the State of Mississip·pi and the Deltra. No·r did his

conclusion account for the advantage of incumbency which white

Republicans now have in the Second Congressional District. !d. at

456-463. Moreover, his razor-thin edge would only protect equal ac

cess, according to his testimony, so long as the white crossover

voting rate reached at least the level which occurred in the 1982

general election. Any slippage would render his conclusion invalid.

ld. Finally, Dr. Hofeller admitted that he had testified in the

Chicago City Council redistricting case, Ketchum v. Byrne, that

a district must be 65% black in total population to give black vote·rs

an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice, and that a

58% black ward was not "a viable black ward." !d. at 465-470.

18

II. THE DISTRICT COURT'S PLAN VIOLATES THE

STRICT GUIDELINES ESTABLISHED FOR

COURT-ORDERED PLANS BY THIS COURT IN

CONNOR v. FINCH.

It is axiomatic that court-ordered redistricting plans

are judged by stricter standards than those designed by

legislatures. Connor v. Finch, 413 U.S. 407, 414 ( 1977).

Two of the areas in which courts must be more careful

than legislatures are compactness of districts and avoid

ance of dilution of black voting strength. As this Court

noted in Connor:

[T]he District Court ... should either draw legisla

tive districts that are reasonably continguous and

compact, so as to put to rest suspicions that Negro

voting strength is being impermissibly diluted, or ex

plain precisely why in a particular instance that goal

cannot be accomplished.

413 U.S. at 425-426.

Avoidance of racial vote dilution is also behind a third

requirement for many court-ordered plans: the use of

single-membe1r districts instead of multimember districts.

Connor v. Johnson, 402 U.S. 690 (1971); East Carroll

Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976).

Among the reasons for this requirement is that multi

member districts ''tend to submerge electoral minorities

and overrepresent electoral majorities." Connor v. Finch,

431 U.S. at 415. While multi-member districting is not

at issue in this congressional districting case, the reason

ing underlying the single-member preference adds to the

court's obligations to avoid the dilution of black voting

strength in redistricting plans.10 It demonstrates that

10 In addition to the requisites cited above, court-ordered plans

must adhere to lower population . deviations, than legislative plans.

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. at 414. The overall deviation in the

Kirksey Plans was less than one-tenth of one percent. Tr. at 166,

168. The District Court did not consider the respective deviations

of its own plan or the Kirksey Plans to be a reason for preferring

one over the other.

19

plans which might otherwise be constitutional and lawful

if passed by a legislature can nevertheless be an abuse of

the court's remedial discretion because they do not elimi

nate the potential for dilution as thoroughly as they

could. See Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds

County, Mississippi, 544 F.2d 139, 152 (5th Cir.) (en

bane) , cert. denied, 434 U.S. 968 ( 1977) .

As noted by the Court in Connor v. Finch, aberrations

from the goal of compactness may reflect potential dilu

tions of black voting strength. Id. at 425-426. See also

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S.--; 103 S.Ct. 2653, 2672-

73 ( 1983). This is particularly true when the district's

sprawling shape makes it difficult for black candidates

who are generally poorer than white candidates-to travel

from one end to the other to campaign. Thus, in Rogers

v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 627 (1982), the Court left un

disturbed a lower court conclusion that, "as a matter of

law, the size of the [district] tends to impair the access

of blacks to the political process." See also S. Rep. No.

97-417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 29 ( 1982) (listing as one

of the probative factors of a Section 2 dilution case the

use of "unusually large election districts"). Plaintiffs'

expert, Senator Henry Kirksey, testified that large con

gressional districts adversely impinge on the efforts of

black citizens to attain equal access to the political proc

ess. December 19-21, 1983 Hearing Transcript at 154-

155.

Here, the Second District in the court-ordered plan

constitutes an awkward, elongated north-south sprawl

which the District Court candidly acknowledged as lack

ing in compactness. App. A, p. 15a. Moreover, to estab

lish that district, the District Court rejected the much

more compact Kirksey Plans which better preserve con

tinguous concentrations of black voting strength. By

leaving portions of the City of Jackson out of the Second

District the court's plan basically "cracks" and divides

those continguous concentrations and sacrifices any hope

of compactness. The court has designed a long and

20

meandering district which does not come close in terms

of black population percentage to the levels which plain

tiffs' expert testimony has shown to be necessary tn give

black citizens an equal opportunity to elect candidates of

their choice. Thus, the District Court failed to follow

Connor's mandate "to make every effort not only to com

ply with established constitutional standards, but also to

allay suspicions and avoid the creation of concerns that

might lead to new constitutional challenges." 431 U.S. at

425. Because the District Court has failed to adhere to

the strict standards of compactness and painstaking

avoidance of dilution of black voting strength, its judg

ment must be reversed.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, · this Court should note prob

able jurisdiction of this appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

FRANK R. PARKER*

PATRICIA M. HANRAHAN

SIDNEY R. BIXLER

LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

1400 I Street, N.W.

Suite400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

ROBERT BRUCE McDUFF

University of Mississippi

Law School

University, Mississippi 38677

(601) 232-5483

JOHNNIE E. WALLS, JR.

WALLS, BUCK & IRVING, LTD.

163 North Broadway Street

Post Office Box 634

Greenville, Mississippi 38701

(601) 335-6001

Attorneys for Appellants

* Counsel of Reco·rd

APPENDICES

la,

APPENDIX A

District Court Opinion.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

GREENVILLE DIVISION

No. GC82-80-WK-O

DAVID JORDAN, et al., .

Plaintiffs,

v.

WILLIAM WINTER, et al.,

Defendants.

No. GC82-81-WK-O

OWEN H. BROOKS, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

WILLIAM F. WINTER, et al.,

Defendants.

(April16, 1984)

ON REMAND F110M THE

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

Before CLARK, Chief Circuit Judge; SENTER, Chief

District Judge; and KEADY, Senior District Judge.

2a

PER CURIAM:

On June 8, 1982, this court ordered into effect on an

interim basis a congressional redistricting plan for the

State of Mississippi. Jordan v. Winter, 541 F.Supp. 1135,

1144-45 (N.D. Miss. 1982). On appeal, the United States

Supreme Court vacated this court's judgment and re

manded the case for further consideration in light of Sec

tion 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, --U.S. --,

103 S.Ct. 2007 (1983).

This court held an evidentiary hearing in December of

1983. On the basis of the evidence adduced at trial and

the pleadings, briefs, and argument of counsel, we con

cluded that the court-ordered plan, or Simpson Plan, vio~

lated amended § 2. The court found that the structure

of the Second Congressional District in particular unlaw

fully diluted black voting strength. Accordingly, on Jan

uary 6, 1984, we entered judgment directing the use,

until the Mississippi Legislature enacts a valid congres

sional redistricting plan, of an interim plan fashioned by

the court with the aid of the parties. Pursuant to the

reservation set out in that final judgment, we now enter

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in support of

that judgment, in conformity with Fed. R. Civ. P. 52 (a).

I. Procedural History

The history of the legislative and judicial efforts to

secure a constitutional congressional redistricting pian

for the State of Mississippi is set out in our prior deci

sion in Jordan v. Winter, 541 F.Supp. 1135 (N.D. Miss.

1982). Only a brief summary is required here.

The 1980 official census revealed a total population dis

parity in Mississippi's 1972 congressional districting pian

of 17.6 7o . Recognizing the constitutional problem posed

by such malapportionment, see U.S. Const. Art. 1, § 2;

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U:S. 533 ( 1964), the Mississippi

Legislature in 1981 enacted S.B. 2001 1 for redistricting

1 1981 Mississippi Laws (Extraordinary Sess.) Ch. 8.

sa.

the state's five congressional districts. The Attorney Gen

eral of the United States, after reviewing the plan pur

suant to the preclearance provisions of Section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c,2 inter

posed a timely objection on March 30, 1982. The Attor

ney General found the plan defective because it divided

the concentration of black majority counties located in

the northwest or '"Delta" portion of the state among three

districts rather than concentrating them in a single dis

trict.3 He concluded that this configuration constituted

an unlawful dilution of minority voting strength.

The Mississippi Legislature did not attempt to enact

another plan or otherwise to obtain preclearance from the

Attorney General. On April 7, 1982, it filed a declara

tory judgment action in the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia seeking judicial preclear

ance of S.B. 2001. Mississippi v. Smith, No. 82-0956.

That action has since been voluntarily dismissed.

The Jordan and Brooks plaintiffs then filed class actions

to enjoin enforcement of S.B. 2001 until it was pre

cleared, to prohibit further use of the 1972 plan because

of population malapportionment, and to secure a court

ordered interim plan for the 1982 congressional elections

and thereafter until change by law. A three--judge dis

trict court was convened pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2284.

2 Mississippi is a covered jurisdiction under § 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, and S.B. 2001 was a change in voting standards., prac

tices, o·r procedures within the meaning of§ 5.

3 The Mississippi Delta consists of the following counties: Bo

livar, Carroll, Coahoma, DeSoto, Grenada, Holmes, Humphre(Y's,

Issaquena, Leflore, Panola, Quitman, Sharkey, Sunflower, Talla

hatchie, Tate, Tunica, Warren, Was.hington, and Zazoo. Missis

sippi's congressional districting plans from 1882 to 1966 all con

tained a district encompassing most of the Delta counties. 541 F.

Supp. at 1139 and n.2. Maps depicting the congressional districts

as they existed under the 1962 plan and under S.B. 2001 are at

tached. District 2 of the 1962 plan contains most of the Mississippi

Delta.

4a~

Jurisdiction was based on 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343

and 42 U.S.C. § 1973j (f). This court declined to place

the unprecleared S.B. 2001 into effect on an interim basis

and concluded that the 1972 plan was unconstitutionally

malapportioned and therefore also unsuitable for interim

use. Jordan v. Winter, 541 F.Supp. at 1142. It thus

limited its consideration to two plans advocated by the

plaintiffs and one advocated by the AFL-CIO as amicus

curiae.

Plaintiffs urged the court to order into effect either of

two plans devised by Senator Henry J. Kirksey, a black

state legislator. Both plans kept the Delta area intact

and achieved black majority districts by combining the

Delta area with predominantly black portions of Hinds

County and the City of Jackson. 541 F.Supp. at 1140.

Plaintiffs' preferred :plan (KirKsey Plan 1) contained

one district that was 64.37% black; the alternative plan

(Kirksey Plan 2) contained one district that was 65.81%

black. Id. The plan urged by the AFL-CIO, the "Simp

son Plan," combined fifteen Delta and part-Delta counties

with six predominantly white eastern rural counties to

produce four majority· white districts and one district

with a black population majority of 53.77%. ld. at 1141.

The Kirksey Plan 1 had a total population variance of

.2150% ; the Kirksey Plan 2 a variance of .230 o/o, and

the Simpson plan a variance of .2141%.

The court was bound by Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S.

37, 102 S.Ct. 1518 (1982), to fashion an interim plan

that adhered to the state's political policies to the extent

those policies did not violate the Constitution or the Vot

ing Rights Act. 541 F.Supp. at 1141. The court deter

mined that the following political policies underlay the

passage of S.B. 2001:

( 1) Minimal change from 1972 district lines; ( 2)

least possible population deviation; (3) preservation

of the electoral base of incumbent congressmen; and

( 4) establishment of two districts with 40 o/o or bet

ter black population.

ld. at 1143. Because the Simpson Plan most nearly ac

corded with the latter three policies, which the court

found to be constitutionally and statuto,rily valid,4 we

ordered it into effect on an interim basis. That plan was

used for the 1982 congressional elections. It is depicted

on a map appended to our prior decision, id. at 1146, and

is statistically described as follows:

Total

District Population Deviation %Deviation Black%

1 604,671 +643 +.1077 26.86

2 604,697 +669 +.1128 63.77

3 503,760 -368 - .0729 31.23

4 503,893 -235 - .0466 45.25

503,617 -611 -.1013 19.84

Although the Second District under the Simpson Plan was

a majority black district (53.77%), it had a. minority

black voting age population of 48.05%.

Analysis of the Simpson Plan under the standard es-:

tablished in amended § 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

reveals its invalidity.

II. Amended Section 2

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended,

presently reads:

Sec. 2 (a) No voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or political sub

division in a manner which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United

States to vote on account of race or color, or in con-

4 As to the first policy, the court reeognized that the validity of

the Attorney General's conclusion that drawing lines fo·r Districts 1,

2, and 3 from east to west unlawfully diluted black voting strength

was the primary issue in the proceedings then pending in the Dis

trict Court of the District of CoJumbia. It therefore accepted, with

out indicating any view as to its validity, the Atto.rney General's

conclusion. 541 F.Supp. at 1143.

6a

travention of the guarantees set forth in section

4 (f) ( 2) , as provided in subsection (b) .

(b) a violation of subsection (a) is established if,

based on the totality of circumstances, it is shown

that the political processes leading to nomination or

election in the State or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by members of a class

of citizens protected by subsection (a) in that its

members have less opportunity than other members

of the electorate to participate in the political proc

ess and to elect representatives of their choice. The

extent to which members of a protected class have

been elected to office in the State or political sub

division is one circumstance which may be consid

ered: Provided, that nothing in this section estab

lishes a right to have members of a protected class

elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the

population.

42 U.S.C.A. § 1973 (West Supp. 1983). The amendment

to Section 2 was designed to eliminate the requirement,

prescribed in City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 100

S.Ct. 2332 ( 1980), that a plaintiff demonstrate inten

tional discrimination to establish a violation of section 2.5

5 S. 1992 amends Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to

prohibit any voting practice, or procedure [which] results in

discrimination. This amendment is designed to make clear that

proof of discriminatory intent is not required to establish a

violation of Section 2 ....

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong. 2d Sess. 2, reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code

Cong. & Ad. News 177 (hereinafter cited as Senate Report). See

Jones v. City of Lubbock, No. 83-1196 (5th Cir. Mar. 5, 1984) ;

Jordan v. City of Greenwood, 711 F.2d 667, 668-69 (5th Cir. 1983) ;

Buchanan v. City of Jackson, 708 F.2d 1066, 1072 (6th Cir. 1983);

Campbell v. Gadsden County School Board, 691 F.2d 978, 981, n.4

(11th Cir. 1982) ; Seamon v. Upham, CA No. P-81-49-CA (E.D. Tex.

1983); Major v. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325, 342 (E.D. La. 1983) ;

Blumstein, Defining and Proving Race Discrimination: Perspec

tives on the Purpose v. Results Approach from the Voting Rights

7a

We reject the contention of the Republican Defendants

that Section 2, if construed to reach discriminatory re

sults, exceeds Congre1ss's enforcement power under the

fifteenth amendment. We agree with the analysis and

conclusion set out in Major v. Treen, .574 F.Supp. 325,

342-349 (E.D. La. 1983) (three judge court), which re

jected a similar assault on the constitutionality of Section

2. We therefore adopt that treatment of this issue with

out repetition here.

The Senate Judiciary Report on the amendment states

that the "results" language of new Section 2 was meant

to "restore the pre- [City of Mobile v.] Bolden legal

standard which governed cases challenging electoral sys

tems or practices as an illegal dilution of the, minority

vote." Senate Report at 27. The Report then enumerates

the factors courts should consider in deciding whether

plaintiffs have established a violation of Section 2. These

factors, derived from the Supreme Court's opinion in

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973), as applied in

this Circuit in Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1287 (5th

Cir. 1973) (en bane), afj'd on other grounds sub. nom

East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S.

636 (1976), include, but are not limited to:

1. The extent of any history of official discrimina

tion in the state or political subdivision that touched

the right of the members of the minority group to

register, to vote, or otherwise to participate in the

democratic process;

Act, 69 Va. L. Rev. 633, 689-70 (1983); Hartman, Racial Vote Dilu

tion and Separation of Powers: An Exploration of the Conflict

between the Judicial "Intent" and the Legislative "Results" Stand

ards, 50 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 689, 726 (1982).

The Republican Defendants have argued that amended Section 2

preserves the requirement of proving discriminatory intent. We

find this argument to be meritless as it runs counter to· the plain

language of amended § 2, its legislative history, and judicial and

scholarly interpretation.

sa:

2. The extent to which voting is racially polarized;

3. The extent to which the state or political sub

division has used unusually large election districts,

majority vote requirements, anti-single shot provi

sions, or other voting practices or procedures that

may enhance the opportunity for discrimination

against the minority group;

4. If there is a candidate slating process, whether

the members of the minority group have been de

nied access to that process;

5. The extent to which members of the minority

group in the state or political subdivision bear the

effects of discrimination in such areas as education,

employment and health, which hinder their ability to

participate e,ffectively in the political process;

6. Whether political campaigns have been charac

terized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. The extent to which members of the minority

group have been elected to public office in the juris

diction.

Senate Report at 28-29 (footnotes omitted). The Report

also cites for consideration, as additional factors proba

tive of a violation of Section 2: ( 1) whether elected offi

cials are unresponsive to the needs of minority group

members; and ( 2) whether the policy underlying the

challenged procedure is "tenuous." ld. at 29. No particu

lar number of these factors need be proved. I d.

III. Amended Section 2 and the Simpson Plan

The court finds that the aggregate of the following

factors shows that the Simpson Plan unlawfully dilutes

minority voting strength.

A. Past Discrimination

That Mississippi has a long history of de jure and de ·

facto race discrimination is not contested. That history

has been often recounted in judicial decisions 6 and in

cludes the use of such discriminatory devices as poll taxes,

literacy tests, residency requirements., white primaries,

and the use of violence to intimidate blacks from register

ing fo,r the vote. The State is a covered jurisdiction un

der the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Attorney Gen

eral has designated 42 of the counties in Mississippi for

federal registrar enforcement of the right to vote.

We find that the effects of the historical official dis

crimination in Mississippi presently impede black voter

registration and turnout. Black registration in the Delta

area is s.till disproportionately lower than white registra

tion. No black has been elected to Congress since the

Reconstruction period, and none has been elected to state

wide office in this century. Blacks hold less than ten per

cent of all elective offices in Mississippi, though they con

stitute 35% of the state's population and a majority of

the population of 22 counties.

The . evidence of socio-economic disparities between

blacks and whites in the Delta area and the state as a

whole is also probative of minorities' unequal access to

the political process in Mississippi.7 Blacks in Mississippi,

6 See, e.g., United States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965) ;

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139, 144 (5th Cir. 1977) ;

Moore v. Leflore County Board of Election Commissioners, 502 F.2d

621, 624 (5th Cir. 1974), af/'g 361 F.Supp. 603, 605 (N.D. Miss.

1972); Mississippi v. United States, 490 F.Supp. 569, 575 (D.D.C.

19'79), aff'd, 444 U.S.1050 (1980).

7 The courts have recognized that disproP<Jrtionate educational

emplo·yment, income level and living conditions arising from

past discrimination tend to d.epress minority political participa

tions, e.g. White [v. Regester], 412 U.S. at 768; Kirksey v.

Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139, 145 [(5th Cir. 1977) ].

Where these conditions are shown, and where the level of black

participation in politics is depressed, plaintiffs need not prove

any further causal nexus between their disparate socio-economic

status and the depressed level of political participation.

Senate Report No. 417, 97th Congress 2d Sess. at 29, n.114.

lOa

especially in its Delta region, generally have less educa

tion, lower incomes, and more menial occupations than

whites. The State of Mississippi has a history of segre

gated school .systems that provided inferior education to

blacks. See United States Commission on Civil Rights,

Voting in Mississippi, pp. 3-4 ( 1965). Census statistics

indicate lingering effects of this past discrimination: the

median family income in the Delta Region (Second Dis

trict) for whites is $17,467, compared to $7,447 for

blacks; more than half of the adult blacks in the Second

District have attained only 0 to 8 years of schooling,

while the majority of white adults in this District have

completed four years of high school; the unemployment

rate for blacks is two to three times that for whites; and

blacks generally live in inferior housing.

B. Racial Bloc Voting

Plaintiffs have established that voters in Mississippi

have previously voted and continue to vote on the basis

of the race of candidates for elective office. The state de

fendants had conceded as much prior to the 1982 elec

tions, but attempted to show at trial that the 1982 cam

paign in the Second District was not characterized by

racial bloc voting. The evidence defendants presented was

that the black Democratic candidate, Robert Clark, re

ceived approximately 15% of the white vote in the 1982

general election and that Clark won the Democratic nomi

nation in a primary contest against white opponents.

The primary election in the Second District conducted

under our prior plan was characterized by confusion and

low voter turnout due to a variety of facto,rs, including

uncertainty about election dates, the recent realignment

of the district, and the lack of an incumbent. The race

was additionally atypical because of a court order allow

ing Republican voters to participate in the Democratic

primary. Clark's victory in the primary was followed by

defeat in the general election-a defeat we find was

caused in part by racial bloc voting. Plaintiffs' proof,

lla

also based on analysis of these election returns, demon

strated a consistently high degree of racially polarized

voting in the 1982 election and previous elections. From

all of the evidence, we conclude that blacks consistently

lose elections in Mississippi because the majority of voters

choose their preferred candidates on the basis of race.

We therefore find racial bloc voting operates to dilute

black voting strength in Congressional districts where

blacks constitute a minority of the voting age population.

Since the Second District under the Simpson Plan does

not have a majority black voting age population, the

presence of racial bloc voting in that district inhibits

black voters from participating on an equal basis with

white voters in electing representatives of their choice.

As the Supreme Court held in Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S.

613, 623, 102 S.Ct. 3272, 3279 ( 1982) :

Voting along racial lines allows those elected to ig

nore black interests without fear of political conse

quences, and without bloc voting the minority candi

dates would not lose eleCtions solely because of their

race.

C. The State Policies Underlying the Simpson Plan

This court previously :adopted the Simpson Plan for

interim use primarily because it conformed to the State

legislature's policy of favoring the division of the black

population of the State into two "high impact" districts

rather than concentrating it into one district. 541 F.

Supp. at 1143-44. The results test required by Section 2

precludes dependence on this policy. The combination of

six predominantly white eastern counties with the Delta

region's black population, when considered in light of the

effects of past discrimination on black efforts to partici

pate in political affairs and the existence· of racially polar

ized voting, operated to minimize, cancel, or dilute black

voting strength in the Second District. Kirksey v. Board

of Supervisors, 554 F.2d at 150; see Major v. Treen, 574

F.Supp. at 354; Hartman, Racial Vote Dilution and Sepa-

12a

ration of Powers; An E xploration of the J'ltdicial "In

tent" and the Legislative "Results" Standards, 50 Geo.

Wash. L. Rev. 689, 695 (1982). Our previous opinion

relied on United States v. Forrest Cou,nty Board of Su

pervisors, 571 F.2d 951 (5th Cir. 1978), and Wyche v.

Madison Parish Police Jury, 635 F.2d 1151 (5th Cir.

1981). Neither involved evidence of racial bloc voting.

They are no longer apposite.

. .

·D. Other Factors

Plaintiffs produced other persuasive evidence that the

political processes in Mississippi were not equally open

to blacks. Evidence of racial campaign tactics used dur

ing the 1982 election in the Second District supports the

conclusion that Mississippi voters are urged to cast their

baJlots according to race.8 This inducement to racially

polarized voting opera ted ·to further diminish the already

unrealistic chance for blacks to be elected in majority

white voting population districts.

IV. The Court-Ordered Interim Plan

In devising a plan to replace our prior plan for the

impending election, we recognized the obligation to: ( 1)

achieve the least possible deviation from the one person,

one. vote ideal, Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 26-27, 95

S.Ct. 751, 765-66 (1975); (2) design a plan that is not

,' s One campaign television commercial si>onsored by the white

candidate whose slogan was "He's one of us" opened and closed

with a view of Confederate. monuments accompanied by this audio

messa-ge:

You know, there's something about Mississippi that outsiders

will never, ever understand. The way we feel about our family

and God, and the traditions that we have. There is a new Mis

sissippi, a Mississippi of new jobs and new opportunity for all

our citizens-. [video pan of black factory workers] We welcome

the new, but we must never, ever forget what has gone before.

[video pan or Confederate monuments] We cannot forget a

heritage that has been ~cred through our generations.

13a

racially discriminatory in either purpose or effect, Mc

Daniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130, 148, 101 S.Ct. 2224,

2235 (1981); and (3) adhere to the state's policies ex

cept to the extent such policies are violative of either the

Constitution or the Voting Rights Act, Upham v. Seamon,

456 U.S. 37, 102 S.Ct. 1518, 1520-21 (1982).

The plan ordered into effect by our final judgment of

January 6, 1984, meets these requirements. The statis

tics of that plan are set out below.

Percent Total

Congress- Variance Voting

sional Total From the Black Age P op. Black % Black

District Population Norm Populat ion % Bla ck (VAP) VAP VAP

504,077 -.0101% 124,136 24.63% 346,074 74,165 21.43 %

2 504,024 -.0206 % 293,838 58.30% 822,719 170,491 52.83 %

3 504,242 + ·0226% 161,710 32.07% 348,524 98,478 28.26%

4 504,187 +.0117% 211,714 41.99% 346,370 129,618 37.42 %

5 504,108 -.0040% 95,808 19;01% 342,754 57,068 16.65%

Range .0432

The interim plan was constructed under these criteria:

create a rural Delta-River area district with a black vot

ing age population majority; achieve minimal deviation

from the ideal population per congressional district of

504,128; create districts containing voters with similar

interests; preserve the electoral base of incumbents; and

comply with the legislative goal of achieving high impact

districts without spHntering cohesive black populations.

We recognize that the creation of a Delta district with

a majority black voting age population implicates difficult

issues concerning the fair allocation of political power.

See A. Howard & B. Howard, The Dilemma of the Voting

Rights Act--Recognizing the Emerging Political Equality

Norm, 83 Colum. L. Rev. 1615 (1983). Although the use

of a race-conscious remedy for discrimination, approved

by the Supreme Court in United Jewish Organizations v;

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 ( 1977), can come into tension -with

Congress' disclaimer in amended § 2 of any right to pro

portional representation, the plan we have adopted fully

rectifies the dilution of black voting strength in the ·· Sec-"

14a

ond District and satisfies the requirements of amended

§ 2 without achieving proportional representation for

blacks in Mississippi.

The court rejected alternative plans offered by plain

tiffs which would achieve a significantly higher black vot

ing age population (approximately 60 o/o) in the Second

District. Plaintiffs argue that a black voting age popula

tion of such preponderance is required for blacks to elect

representatives of their choice. Amended § 2, however,

does not guarantee or insure desired results, and it goes

no further than to afford black citizens an equal oppor

tunity to participate in the political process. In comment

ing upon the § 2 amendment, Senator Dole, a leading

sponsor of the compromise legislation, stated: "Citizens

of all racesare entitled to have an equal chance of elect

ing candidates . of their choice, but if they are fairly af

forded that opportunity and lose, the law should offer no

remedies." Senate Report at 193. In the opinion of this

court, after considering the totality of the circumstances,

the creation of a Second District with a clear black vot

ing age population majority of 52.83% is sufficient to

overcome the effects of past discrimination and racial

bloc voting and will provide a fair and equal contest to

all voters who may participate in congressional elections.

Credible expert testimony received in this case supports

this conclusion. Additionally, plaintiffs' plans are an ob

vious racial gerrymander which would bring into the Sec

ond District overwhelmingly black sections of the City of

Jackson and its suburbs; these inner-city, metropolitan

areas have little in cdmmon with the interests of the pre·

dominantly rural Delta region. Also, plaintiffs' plans un

necessarily dilute black voting strength in the Fourth Dis

trict. The Fourth District presently has a black popula

tion of 45.25%. The evidence presented indicates this is

a factor in making the Fourth District representative

reasonably receptive and sensitive to the needs of the

black community. The plan adopted necessarily reduces

the black population of the Fourth District to 41.99%.

15a