Beecher v. Alabama Brief in Support of Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

October 15, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Beecher v. Alabama Brief in Support of Petition for Rehearing, 1974. d874be24-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6ea6541b-93bc-4e86-b02d-6ccef259d270/beecher-v-alabama-brief-in-support-of-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

\

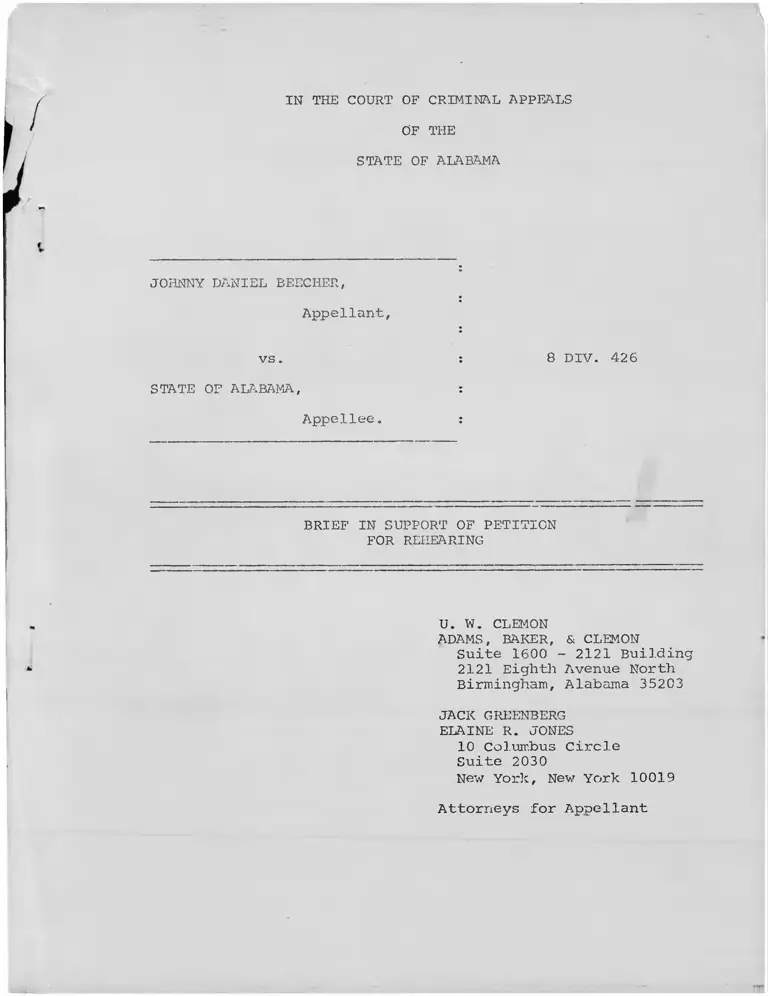

IN THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS

OF THE

STATE OF ALABAMA

JOHNNY DANIEL BEECHER,

Appellant,

vs.

STATE OF ALABAMA,

Appellee.

8 DIV. 426

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION

FOR REHEARING

U. W. CLEMON

ADAMS, BAKER, & CLEMON

Suite 1600 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

ELAINE R. JONES

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Statement of the Case .......................... •..........1

II. Statement of the Facts ...... ............................ii

III. Propositions of Law .................................... iii

IV. Argument ..................................................1

1. This Court Misconceived the Constitutional

Standard for Determining a Prima Facie Case

of Jury Discrimination and Erred in Imposing

an Incorrect Burden of Proof on Appellant......... 1

A. Appellant Contends That This Court's

conclusion That the Evidence Did Not

Establish a Prima Facie Case of Racial

Discrimination in ithe Selection of

Jurors was Based on a Misconception

of the Constitutional Test for Determining

When a Prima Facie Case of Racial— - --- -*

J / J . O V . . J , J . U U . U U I . . J . V . U 1 0 . 0 U J . 1 W V A A • e * • • c « > » * « . e o o e e * c, „ „ * * .L

B. Appellant Met His Burden Of Establishing A

Prima Facie Case of Racial Discrimination.....4

2. This Court Applied an Incorrect Legal Standard

Inconsistent with the Due Process Clause of the

Sixth and Four!: 'enth Amendments of the Con

stitution of the United States in Judging the

prejudicial Effect of Extrajudicial Influences on

the Members of the Jurt Venire in AppellentHs

Case ..............................................13

A. The Trial Court and This Court Applied an

Improper Legal Test for Determing the

Impartiality of Appellant's Venire........ .13

B. On This Record the Denial of Appellant's

Motion to Individually Voir Dire Jurors

Out of the Presence of One Another is

Reversible Error....................... 16

TABLE OF CONTENTS (cont.)

III. This Court Erred in its Review of the Totality

of Circumstances and the Standard of Voluntariness

It Applied in Affirming the Admissibility of an

Incriminating Statement Attributed to Appellant ....22

A. The Record Reflects Inherently Coercive

Circumstances Surrounding the Alleged

Incriminating Statement .................... 22

B. This Court Erred in Not Looking to the

Totality of the circumstances in Determining

"Voluntariness" .............................28

IV. This Court's Finding That the Record Does Not

Show the Context of the District Attorney's

Statement That "No one Took the Stand to Deny It"..34

V. It Was Reversible Erroe for the Trial Court to

Admit into Evidence Testimony on "Tracking" Which

Did Not Comply with the Proper Evidentiary

Stanfiarrl for Admi sslbil.i tv ........................ 38

VI. Conclusion

V*.

Statement of the Case

Appellant herein incorporates by reference the Statement

of the Case set out in Appellant's Brief on Appeal. This

Court filed its opinion on October 1, 1974. Appellant has

fifteen days to file a Petition for Rehearing. The Petition for

Rehearing will be timely filed on October 14, 1974.

v

i

Statement of the Facts

Appellant herein incorporates by reference the facts

meticulously set out in Appellant's Brief on Appeal. V7ith

regard to the prosecutor's comment "no one took the stand

to deny it," the fact that the comment was made by the

district attorney in referring to the testimony of Ken

Phillips is uncontradicted and undenied in this regard

(Tr. 1201, 1202).

11

PROPOSITIONS OF LAW

I.

THIS COURT MISCONCEIVED THE CONSTITUTIONAL

STANDARD FOR DETERMINING A PRIMA FACIE CASE

OF JURY DISCRIMINATION AND ERRED IN IMPOSING

AN INCORRECT BURDEN OF PROOF ON APPELLANT.

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972).

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953).

Brooks v. Be to, 366 F-2d 1 (5t.h Cir. 1966).

Carmical v. Craven, 457 F.2d 582 (9th Cir. 1972).

Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, 396

U.S. 320 (1970).

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950).

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 (1964).

nxxx v. xcxaa, oxo u .d . *tuu x̂̂ '+x; .

Mobley v. United States, 379 F.2d 768 (5th Cir. 1967).

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1881).

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935).

Rabinowitz v. United States, 366 F.2d 34 (5th

Cir. 1966). t*

Salary v. Wilson, 415 F.2d 467 (5th Cir. 1969).

Scott v. Walker, 358 F.2d 561 (5th Cir. 1966).

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940).

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880)

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970).

United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53

(5th Cir., 1962).

Wansley v. Slayton, 487 F.2d 90 (4th Cir. 1973).

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967).

iii

II.

THIS COURT APPLIED AN INCORRECT LEGAL STANDARD

INCONSISTENT WITH THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE

SIXTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS OF THE CONSTITU

TION OF THE UNITED STATES IN JUDGING THE PREJUDICIAL

EFFECT OF EXTRAJUDICIAL INFLUENCES ON THE MEMBERS OF THE JURY VENIRE IN APPELLANT'S CASE.

Coppedge v. United States. 272 F.2d 504, cert. denied, 368 U.S. 855 (1961).

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 (1961).

Marshall v. United States, 360 U.S. 310 (1959).

United States ex rel. Doqqett v. Yeaqer, 472 F.2d 229 (1973). " “ ' '

III.

THE COURT ERRED IN ITS REVIEW OF THE TOTALITY OF

CIRCUMSTANCES AND THE STANDARD OF VOT.TTNTARTNFSS

IT APPLIED IN AFFIRMING THE ADMISSIBILITY OF AN

INCRIMINATING STATEMENT ATTRIBUTED TO APPELLANT.

Beecher v. Alabama, 389 U.S. 35, 88

189 (1967).

S. O rf •

Beecher v. Alabama, 408 U.S. 234, 92

(1972).

S. ct . 2282

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478,

1758 (1964).

84 s . Ct.

Glinsey v. Parker, 491 F.2d 338 (6th Cir. 1974).

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368, 84 S

(1964).

. Ct. 1774

Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201,

Ct. 1199 (1964).

84 S.

Mathis v. United States, 391 U.S. 1,

1503 (1968).

88 S. Ct.

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86

102 (1967).

S. Ct •

IV

ppr.l<- v. pate, 367 U.S. 443, 528, 534 (1963) .

Spano v. New York, 360 U.S. 315, 79 S. Ct.

1202 (1959)

Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293, 87 S. Ct.

1967 (1967) .

United States v. Bekowies, 432 F.2d 8 (9th

Cir., 1970).

United States ex--rel O'Connor v. The State of

New Jersey, 405 F.2d 632 (3rd Cir., 1969).

*

V

I

IV.

THIS COURT'S FINDING THAT THE RECORD DOES NOT

SHOW THE CONTEXT OF THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY'S

STATEMENT THAT "NO ONE TOOK THE STAND TO DENY

IT" IS ERRONEOUS.

Stareet v. State, 266 Ala. 289, 96 So.2d

686 (1957).

V.

IT WAS REVERSIBLE ERROR FOR THE TRIAL COURT

TO ADMIT INTO EVIDENCE TESTIMONY ON "TRACKING"

WHICH DID NOT COMPLY WITH THE PROPER EVIDENTIARY

STANDARD.

Allen v. State, 8 Ala. App. 228, 62 So. 971

(1913).

■q-i-i>-vc? tr c 940 Ala. 587 . 200 So. 418

T T 94T ) • "

Gallant v. State, 167 Ala. 60, 52 So. 739

(1910) .'

Little v. State, 145 Ala. 662, 39 So. 674 (1905).

Richardson v. State, 145 Ala. 46, 41 So. 82 (1906).

%•

vi

I.

THIS COURT MISCONCEIVED THE CONSTITUTIONAL

STANDARD FOR DETERMINING A PRIMA FACIE CASE

OF JURY DISCRIMINATION AND ERRED IN IMPOSING

AN INCORRECT BURDEN OF PROOF ON APPELLANT.

A. Appellant Contends That This Court's Conclusion

That The Evidence Did Not Establish A Prima Facie

Case Of Racial Discrimination In The Selection Of

Jurors Was Based On A Misconception Of The Con

stitutional Test For Determining When A Prima Facie

Case Of Racial Discrimination Is Shown.

For historical reasons, the early decisions of the Supreme

Court of the United States dealing with jury selection involved

deliberate discrimination against Blacks. Thus, in Strauder

v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1800)., the issue was the con

stitutionality of a state statute that explicitly excluded Blacks

from jury service. Other cases involved undenied, intentional

exclusion by the administration of statutes racially neutral

on their face. See, Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1881). In

later cases purposeful discrimination was denied; the result was

the rule that, in the face of total or near-total exclusion of

Blacks over a period of time, such '"denials on the part of jury

commissioners were not sufficient to overcome a prima facie case

of jury discrimination. Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935).

A natural outgrowth of these cases was the more recent rule

that where there is a significant disparity in the number of

Blacks chosen (short of total exclusion) and there is an opportunity

to discriminate because the race of prospective jurors was known,

then it would be presumed that the opportunity had been seized

upon despite sworn denials by jury commissioners. Avery v. Georgia,

345 U.S. 559 (1953); Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967);

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972). Similarly, when

the disparity occurred in part at a point in the selection

process where subjective judgments as to qualifications were

exercised, then a constitutional violation was established.

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970).

The Supreme Court of the United States in Smith v. Texas,

311 U.S. 128 (1940), applied a somewhat different standard than

deliberate or purposeful discrimination. The Court also held

unconstitutional, methods of jury selection that had the effect

of excluding Blacks irrespective of whether jury commissioners

intended discrimination when they adopted those methods because

they resulted in non-representative juries. Thus, in Hill v.

Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942), the Court ordered an indictment

quashed on a showing that jury commissioners had not acquainted

themselves with the Black community, thus failing in their duty

"not to pursue a course of conduct in the administration of

their office which would operate to discriminate in the selection

of jurors on racial grounds." ][d. at 404. Accord: Cassell v.

Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950). And in Alexander v. Louisiana, supra,

the Court stated that "racially neutral selection criteria and

procedures" must be used.

In concluding that appellant failed to make out a prima

facie case of discrimination, at least, in part because "the

evidence disclosed no purposeful design by the Commissioners not

to include qualified blacks on the roll . . .," this Court's

decision is in direct conflict with the Supreme Court cases

discussed above. (Slip Opinion, p. 10).

2

Moreover, the Fifth Circuit's decision in United States

ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53 (1962), cert, denied, 372

U.S. 924 (1963), squarely holds that purposefulness is not a

necessary element of a prima facie case of racial discrimination

in jury selection. After discussing a number of cases which

contain terms such as "purpose to discriminate," "intentional

discrimination," "intentional exclusion," and "purposeful

systematic non-inclusion because of color," the Seals court

said:

These same cases, however, and others, recognize

a positive, affirmative duty on the part of jury

commissioners and other state officials, and show

that it is not necessary to go so far as to

establish ill will, evil motive, or absence of

good faith, but that objective results are largely

to be relied on in the application of the con

stitutional test. 304 F.2d at 65.

The question is whether the jury commissioners, given the

purest of motive, have conformed their "method of selection to

a system that will produce jury lists reasonably approximating

that cross-section [of their community.]" Smith v. Yeager, 465

F.2d 272, 282 (3rd. Cir. 1972). Accord: Carmical v. Craven, 457

F.2d 582, 586 (9th Cir. 1972).

Review of the above Supreme Court and Circuit Court cases

demonstrates that the burden of proof on appellant was to show

a substantial disparity in the representation of Blacks and whites

on the jury list and, at most, a point in the selection process

where subjective judgments of those responsible for the selection

of juries were likely to contribute to the disparity. See, e_.c[. ,

Turner v. Fouche, supra.

3

B. Appellant Met His Burden Of Establishing A

Prima Facie Case Of Racial Discrimination.

1. Appellant demonstrated a substantial

disparity in the representation of

Blacks and whites on the jury lists.

Appellant's undisputed statistical figures show that in

1970 the total population of Lawrence County, Alabama was 27,281.

Of that number, 5,114 or 18.7% were Black. The total number of

persons 21 years and older and therefore presumptively qualified

for inclusion on the jury rolls was 15,289. Of this number,

2,355 or 15.4% were Black.

Appellant's evidence as to the racial composition of the

!_/jury roll showed that only 5.2% of the total were Blacks, and

this evidence was buttressed by a showing that the percentage

of Blacks on each of thirteen of sixteen general venires drawn

in 1972 ranged from a low of 1.3% to a high of 8.3%. Of that

total of 1,015 names appearing on those thirteen venires, only

2 J49, or 4.8% were Blacks.

Moreover, it was stipulated by the parties that of the 70

regular and 5 special jurors originally drawn for the trial in

V

April, 1973, only 5 or 6.7% were Blacks. A second venire was

drawn in June, 1973. Of 80 jurors summoned, only 4 or 5.0% were

Blacks. Of 58 jurors actually present on the day of organization.,

only 3 or 5.2% were Blacks. The jury which convicted appellant

was all-white.

1/ In Appellant's Brief the percentage of 5.1% was used;

however, the accurate figure is 5.17% which correctly rounds off

to 5.2% as used by this Court.

2 / The contention that the figures in this paragraph are not

accurate or conclusive, is considered at pp. 9, 10, 11, infra.

4

Appellant respectfully urges that this Court misapprehended

the above facts. The situation with regard to the jury list in

Lawrence county can be stated as follows: out of every 100 names

drawn from a properly compiled jury list, it would be expected

_3_/that 15 would be those of Blacks. However, on the master

jury list, only 5 out of every 100 names were Black.

Thus, the underrepresentation of Blacks on the revised jury

list was far greater than 10%. Rather, Blacks were under-

A Jrepresented on the master jury list by over 66%.

The Supreme Coxirt has made it clear that the relevant

figure in determining whether a particular jury list adequately

represents a cross-section of the community is not the difference

between the percentage of Blacks in the community and their

percentage on the jury list. Rather, what is significant is

the percent of the Black community excluded from service, or,

in other terms, the percent of underrepresentation. In Alexander

v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625, 629 (1972), the Court stated the

facts thusly:

3/ All figures are rounded off to the nearest whole number.

4/ The following table compares the expected number of Black

jurors per 100 (based on eligible Blacks being 15.4% of the

population) with the actual number per hundred:

Expected No.

Black Jurors

per 100 Juries

Actual No.

per 100 in % Under-

Master List representation

15.4 5.2 66.2

5

In Lafayette Parish, 21% of the population

was Negro and 21 or over, therefore presumptively

eligible for grand jury service. Use of question

naires by the jury commissioners created a pool

of possible grand jurors which was 14% Negro, a

reduction by one-third of possible black grand

jurors. The commissioners then twice culled this

group to create a list of 400 prospective jurors,

7% of whom were Negro — a further reduction by

one-half.

Thus, in Alexander, the Court did not substract 7% from

14% for a disparity of only 7%, but calculated that the reduction

- Vwas one-half, d̂ .ep , 50%. Of course, in the present case,

when the deviation of the master list from a cross-section is

seen to be 66.9% rather than only 10%, it must be concluded

5 / The of vmHf*̂ 270̂ 2?̂ *SOTlf ̂ t2.OP is O'? 1C113 +" P* H

follows: The actual number of Blacks per 100 is divided by the

expected number per 100 (based on their percent of the population).

The figure obtained is the percent representation. That figure

is substracted from 100% (representing perfect representation) and

the result is the percentage of underrepresentation, i_. e_. , the

percent of eligible blacks excluded from servive.

Thus, <2.c[. , in a county 20% black but with only 8% blacks on

the jury list, the calculation is as follows:

V8 (actual no./lOO) _ 40%.20 (expected no./lOO) ~

40% — the percentage of the black population represented

on the list. The percentage of Blacks excluded is:

100% - 40% _ 60%.

Thus, the Black population would be underrepresented by 60%, and

not 12%.

The calculation of the percent underrepresentation on the

revised grand jury list in this case is as follows:

5.2 = 33.8% 100% - 33.8% = 66.2%15.4

6

that constitutional standards have not been met. Cf. Wansley

v. Slayton, 487 F.2d 90, 100, 101 (4th Cir. 1973)(underrepresenta

tion of 50% or more is a prima facie case of racial discrimination).

2. Appellant demonstrated that the selection process allowed for subjective judgments

which were likely to contribute to the

disparity in Black-white representation

on the jury rolls.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that the process most

relied upon in compiling the master list is the key-man system.

This process of contacting "leading citizens" to recommend

qualified persons for the jury list was exacerbated by the fact

that the commissioners and the clerk were generally unfamiliar

with the Blacks in Lawrence County. Moreover, the unfamiliarity

with the overall racial composition of the jury list and the lack

of affirmative action to insure that Blacks and whites were

included in proportions which would provide a reasonable cross-

section was in dereliction of their affirmative duty to acquaint

6 / An illustration may be used to show why subtracting per

centages is misleading. Suppose there are three counties: County

A is 10% black, B is 20% black and C is 80% black. An investiga

tion discloses that the percentage of Blacks on the jury lists of

the three counties is as follows: A, 0%; B, 10%; C, 70%.

If, in determining whether the jury lists adequately reflect

a cross-section of the community, the percentage on the list is

merely subtracted from the percent in the county, the anomalous

result is reached that in each case the underrepresentation is the

same, i.e., 10% (10 - 0 = 10; 20 - 10 = 10; 80 - 70 - 10).

Undisputably, however, a jury list with no blacks in a county 10%

black is no where near as representative of the community as is a

list 70% black in a county 80% black.

If the percentage underrepresentation is used, however, an

accurate picture is obtained. In County A blacks are 100% under

represented, in County B, 50%, and in County C, 12.5%.

7

themselves with Blacks. Ehcj_. , Avery v. Georgia, supra; Cassell

v. Texas, supra; Smith v. Texas, supra; Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d

1 (5th Cir. 1966) ; United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, supra;

Scott v. Walker, 358 F.2d 561 (5th Cir. 1966). Cf. Smith v.

Yeager, supra, citing Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County,

396 U.S. 320 (1970); Carmichael v. Craven, supra.

This Court recognized the inadequacy of the procedures

employed. (Slip opinion, p. 10). However, the court was not

at that time considering this issue within the proper context

and applying the appropriate standard. But in case after case,

the "key-man" system and the attendant circumstances of the

commissioners' general unfamiliarity with Blacks the

commissioners' lack of effective affirmative action to insure

that BiacKs and whites were included on the jury Irsts in

representative proportions; and, the commissioners' failure to

pursue a course of action which would provide jury lists reasonably

approximating a cross-section of the community — has been held

to be constitutionally infirm. Where this system results in

substantial underrepresentation of Blacks, it is prima facie

racially discriminatory. Smith v. Texas, supra; Salary v. Wil_son,

415 F.2d 467 (5th Cir. 1969); Rabinowitz v. United States, 366

F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1966); Smith v. Yeager, supra. Such under

representation appellant has shown.

8

not identify them — when shown a list of the names on the

Jz/actual venires. Appellant's witnesses were selected on

the basis of their familiarity with Blacks, identified an

JL/average of 4 to 5. Scott v. Walker, 358 F.2d 561 (5th Cir.

1966), clearly demonstrates that the type of evidence presented

by appellant is to be greatly preferred over the oral,

generalized testimony produced by the state:

Thus, it is that, instead of producing the

lists with witnesses who could state the race

of persons listed on each of them . . . , which

would have proven without any doubt, if it had

been true, that there were more than a token

token number of Negroes listed, respondent

depended on oral testimony of the three

commissioners. . . . [N]ot one of them

identified a single Negro as having been placed

by him on the general venire list. . ., and they

testified as to their own participation in the

jury selection system [including Blacks on the

general venire] in only the vaguest terms, i.e. ,

"one to three," "several," "quite a few." 358

F.2d at 568.

7 / The issue is the number of Blacks on the master lists.

And while appellant strongly urges that his data as to the number

of Blacks on the 13 venires considered by Burney, J. is ample

support of his contentions as to the number on the master list, it is not necessary to conclude that J. Burney's statements were

untrue, since it is logically consistent — although highly

improbable — that some venires contained 8 to 10 blacks, but

that the master list was only 5.2% black.

8 / The State would also contend that because some of

appellant's witnesses stated that they did not know every Black

in Lawrence county this was sufficient to rebut appellant's

data. Surely, it is unreasonable to require a single witness

to know every person 21 years or older in an entire county or

in any area where there is a large number of people. As shown,

the procedure of calling witnesses to make racial identifications

is an appropriate and accurate procedure in this type of case.

Scott v. Walker, supra.

10

Appellant's contention that the derogation of the

accuracy of his statistics is unwarranted is even more

compelling when the attendant circumstances are considered.

First, the trial court denied appellant's motion to inspect

the jury rolls in advance. Cf. Scott v. Walker, supra, at 567;

Mobley v. United States, 379 F.2d 768, 772, 773 (5th Cir.

1967).

Second, the trial court denied appellant the opportunity

to explore the possibility that previous jury lists contained

racial designations. This inquiry was relevant to two regards.

1) If in fact, the previous jury lists contained racial

designations, then those lists would have provided a means of

determining the race of a substantial number of jurors —

especially in light of tne tact that mere was testimony

indicating that the current lists were derived in part from

the previous lists. C_f. Scott v. Walker, supra at 568;

Mobley v. United States, supra at 773; and 2) the inquiry was

relevant to the issues of whether there was a clear opportunity

to discriminate and whether there existed a pattern and practice

of racial discrimination.

9 / Although appellant clearly demonstrates that he was not

required to show purposeful discrimination, he should not have

been foreclosed from pursuing evidence on this issue. cf.

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 (1964). It must be noted here

that in addition to other procedural deficiencies in appellant's

trial, infra, the trial court's denial of the motion to inspect

the lists in advance and its exclusion of the evidence as to past

practices, rises to the level of a denial of an adequate hearing.

Coleman v. Alabama, supra; Mobley v. United States, supra.

11

This Court's statement that "there was no evidence to

demonstrate the proportion of'Negroes actually qualified as

jurors under the statute” (slip op, at p. 11) contradicts the

Court's recognition that Blacks 21 years of age and older are

presumptively qualified (slip op. p. 11).

Further, there is no burden on the Black community to

seek inclusion on the jury rolls and the commissioners'

positive affirmative mandate to insure a reasonably

representative cross-section of the community cannot be

discharged by — nor can the state rely on — the failure

of "black leaders" or "key-man” to seek to include Blacks as

this Court intimates. (Slip Opinion, p. 10). As the Fifth

Circuit said in Salary v. Wilson, 415 F.2d 467, 472 (5th Cir.,

1969):

[T]hose charged with administering the jury

selection machinery may not transfer to the

Negro community, or to any other segment of the community, the responsibilities placed by

law upon them, nor may they transmit insufficient

methods into effectual ones on the basis that

Negroes are not sufficiently responsive.

For all the foregoing reasons, appellant clearly

demonstrated that Blacks were systematically excluded from

the master jury rolls of Lawrence County. On this basis,

appellant must be granted a new trial.

12

II

THIS COURT APPLIED AN INCORRECT LEGAL

STANDARD INCONSISTENT WITH THE DUE

PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE SIXTH AND

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS OF THE CONSTI

TUTION OF THE UNITED STATES IN JUDGING

THE PREJUDICIAL EFFECT OF EXTRAJUDICIAL

INFLUENCES ON THE MEMBERS OF THE JURY

VENIRE IN APPELLANT'S CASE.

A. The Trial Court And This Court Applied An Improper

Legal Test For Determining The Impartiality Of

Appellant's Venire.

This Court and the trial court erroneously imposed upon

the appellant the burden of demonstrating that the newspaper

accounts had actually prejudiced the jury against him.

Marshall v. United States, 360 U.S. 310 (1959) Irvin v. Dowd,

366 U.S. 717 (1961). The rule of Marshall and Irvin, is

that impartiality is not a technical conception. Irvin, supra,

at 724. In Marshall, supra, the High Court ordered a new

trial despite the statement by jurors, as here, that they

would not be influenced by the news articles. Irvin re

affirmed the rule in Marshall that the effect of prejudicial

information is not cured by the statement of a juror that he

will not be influenced by adverse publicity.

Here, the build-up of prejudice is clear and convincing,

Irvin, supra at 724. Close examination of the record includes

13

C. Appellant's Prima Facie Case Of Racial

Discrimination Was Not Rebutted By The

State's Evidence.

Appellant's procedure for determining the number of

Blacks on the jury list is an appropriate and sanctioned method

of establishing the racial composition of a jury list. For

example, in Scott v. Walker, supra, the Fifth Circuit Court

of Appeals in considering a claim by appellant Scott that only

a token number of Blacks were on the jury lists said that

"producing the lists with witnesses who could state the race

of persons listed on each of them . . . would have proven

without any doubt . . . that there were more than a token

number of Negroes listed." 358 F.2d at 568 (emphasis added).

Second, once appellant had made a showing of the number

of Blacks on the jury list, it was incumbent upon the State

to go forward and show that there were more Blacks if, as it

contends, there were in fact more Blacks on the lists. Id.

Or as the United States Supreme Court in Turner v. Fouche, supra,

stated: W

"If there is a 'vacuum' it is one which the

State must fill, by moving in with sufficient

evidence to dispel the prima facie case of

discrimination." 396 U.S. at 361.

This burden was not met by the oral testimony of a

commissioner that a former commissioner had told him the list

was 20% Blacks; particularly in view of the fact that it was

shown that he knew less than 100 Blacks. Nor was it met by the

oral statement of a witness that he had observed an average of

8 to 10 Blacks on venires — especially where the witness could

9

articles from the nine year coverage of the case. The

testimony of the general manager of the daily newspaper in

Lawrence County, the sites of the trial, in explaining

massive first and second page coverage of appellant's case

testified, that there was "a great deal of interest in the

case" in Lawrence County (R. 112) and that no other murder

case had received such consistent coverage (R. 137, 138).

The record reflects that appellant introduced over

eighteen (18) newspaper articles which contained facts which

jurors were not entitled to know about the appellant and

wwhich were devastating to his cause. Coppedge v. United

qtafp.q. 772 F.2d 504. 508 cert, denied 368 U.S. 855 (1961) .

Among the many details of the two previous convictions were

specific reports of the content and circumstances surrounding

two prior confessions, both of which were reversed by the

Supreme Court (R. 87, 127). Further, there was reporting

that the appellant, a black male, had hence been convicted

of murdering a pregnant white woman. There was not in this

trial nor has there ever been evidence of pregnancy. The

evidence is therefore clear and convicing that the avalanche

10/ See Footnote 16 (Appellant's Brief at p. 34).

14

of newspaper articles, all of which are in the record before

this Court contained prejudicial information which should not

iyhave come to the knowledge of the jury. Marshall, supra.

The record is replete with evidence of the newspaper,

radio and television coverage afforded appellant's trial

which purported to include "facts" from his previous trials.

It requires little argument "that the newspaper articles con

tained facts which should not have come to the knowledge of

the jury." Coppedge, supra at 508. The details of the prior

confessions of appellant in an inflammatory case such as this

is clearly prejudicial. "It is too much to expect of human

nature that a juror would volunteer in open court, before

his fellow jurors that he would be influenced in his verdict

by a newspaper story. . . . " Coppedge, supra at 508. Also

see Marshall, supra; Irvin, supra.

Of the forty-four veniremen who were qualified for jury

V«service, twenty-five admitted they had read or heard about

the Beecher case (Tr. 466-596). Additionally, on the jury

which tried appellant, five jurors, as recently as the day

before trial, had read an article setting forth the "facts"

and procedural history of appellant's cases (D. Exs. 18, 19).

11/ See Statement of the Facts (Appellant's Brief at pp. 9-12).

15

As in Dowd, supra, the finding of impartiality of the jurors

in this case does not meet constitutional standards.

The third trial of this appellant did not begin when

the petit jury was empaneled and the first witness sworn.

It began during the pre-trial publicity; appellant was con

victed during the public voir dire when opinions cemented and

veniremen recounted from newspaper coverage the events in

Beecher's first and second trials. The Supreme Court of the

United States had twice reversed this case on confession

issues. With the magnitude and horror of the crime with

which he again stands convicted, on this record placing the

D iin 'c lt if i O n L i i x s d j p p s l . i c i r i ' t o i~ G hG V v^nc r \ -i n r l n /r> r\ -P

- w — — — j r ------ J --- -------------- -----------

veniremen when there is a clear showing of probable bias,

offends the due process clause and the Sixth Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States. This appellant in

this, his third trial, has not been afforded a fair and

W

impartial jury to which he is constitutionally entitled.

B. On This Record The Denial Of Appellant’s Motion To

Individually Voir Dire Jurors Out Of The Presence

Of One Another Is Reversible Error.

In the face of all of the pre-trial publicity, a great

deal of which over half of the prospective veniremen had

16

12/

either read or heard about (exactly 25 out of 44 veniremen),

the trial judge denied appellant's motion to voir dire the

jurors individually out of the presence of each other (R. 505;

Tr. 466-67). Appellant urges upon this Court that this was

manifest error and mandates a reversal of his conviction.

Those jurors who may have survived the blanket of publicity

which weighed the balance against the appellant, were most

assuredly exposed to it during the collective voir dire.

United States ex rel. Doggett v. Yeager, 472 F.2d 229 (1973),

Coppedge, supra. Of the three jurors who were challenged for

cause, two of them detailed their bias and prejudices against

this appellant based on "discussions" in which they had

engaged (R. 660, 575, 685) . One juror stated in the presence

of the other jurors that her daughter had outlined the facts

of appellant's case [as read in the newspapers by the daughter]

and that the venirewoman did not doubt the facts of the case

13/

as reported by the daughter (R. 580). One venireman (Goodwin)

reported in the presence of the others, "I think he is guilty

because if he hadn't been, he wouldn't have been stuck twice

ljy See Appellant's Brief at p. 34.

13/ See Appellant's Brief at p. 34. See statements made in

presence of all jurors. App. Br. at p. 12-13, R. 498.

17

before" (R. 643, 644, 646). The testimony of venireman

Littrell is a study in inflammatory mythology (R. 660).

The Court of Appeals in Coppedge, supra, emphasized

that:

[h]ad one or more of them [jurors] said they

would be so influenced [by newspaper articles]

and especially if they had explained why the

damage to the defendant would have spread to

the listening other jurors. In view of the

nature of the articles, the Court should have

made a careful, individual examination of

each of the jurors involved, out of the presence

of the remaining jurors as to the possible

effect of the articles.

Coppedge, supra, 272 F.2d at p. 608.

This the trial judge failed to do. In this case, with twenty-

five members of the panel — over 58% — who had read or

discussed articles concerning the previous trials, reported

confessions, and inflammatory circumstances surrounding the

crime with which appellant is charged, the trial judge denied

appellant's motion to question these jurors individually out

of the presence of the other jurors. Not only did this error

cause jurors to sit who had the probability of partiality

but the entire procedure spread the damage to the listening

jurors. Marshall, supra; Irvin, supra; Coppedge, supra.

The United States Supreme Court has clearly disapproved of

conducting an examination to determine prejudice in the

presence of other veniremen. Irvin, supra, 366 U.S. at 728;

18

Marshall, supra. In Marshall, the examination of each of

the seven jurors who had seen one or more of the news

articles was conducted individually outside of the presence

of the remaining jurors. And although assured by the jurors'

assurances they would disregard what they had read, the Court

found that:

The prejudice to the defendant is almost

certain to be as great when that evidence

reaches the jury through news accounts as

when it is part of the prosecutor's

evidence. 360 U.S. at 312-13.

Even the safeguards afforded the defendant in Marshall have

been denied this appellant. Initially, appellant's motion

for a change of venue from Cherokee to Lawrence County was

denied by the trial judge on March 12, 1973 (R. at ).

Since the situs of the second trial was in Cherokee

County and the case had received much publicity, most of

which is in the record before this court, and was before the

trial court appellant moved for a change of venue for

appellant's third trial (R. at ). The trial judge,

Judge Powell, denied that motion stating that in his opinion

the appellant could fairly be tried a third time in Cherokee

County and so set a trial date of March 12, 1973.

Appellant's counsel on the duly appointed date sought

vainly to select a jury. A panel of 56 jurors was called

and the trial judge denied appellant's motion to voir dire the

19

jurors individually out of the presence of one another;

and the court excused over 30 veniremen challenged for

cause by the appellant when responses such as the following

were made:

(1) Those two convictions would be in the

back of my mind during the trial of

the case.

(2) Since Beecher has twice been found

guilty of the murder, he is "either

guilty or probably guilty" of that

offense. (Exhibit B)

(3) I go along with the 24 jurors [in the

two previous trials] who have said he

is guilty.

Eventually, the entire panel was tainted with bias against

the appellant.

Only when the trial judge found it impossible to impanel

a jury in Cherokee County, after one and one-half day of voir

dire did he grant appellant's motion for a change of venue,

whereupon the trial was moved to tfie judge's "home county"

of Lawrence County, Alabama.

Again requiring appellant's counsel to voir dire jurors

in the presence of one another, the trial judge refused to

grant a change of venue upon a showing of probable bias.

The trial judge simply was not inclined to move the case a

second time although it meant moving "to a county free from

prejudice." Code of Ala. Tit. §269.

20

Biased opinions formed from specific knowledge by

members of the jury panel of the factual details surrounding

the two previous trials and convictions of this appellant,

coupled with the collective voir dire of the jury panel in

the presence of one another in which individual jurors

expressed additional bias based on rumor, supposition and

hearsay, deprived appellant of his Sixth Amendment right to

an impartial jury.

21

Ill

THIS COURT ERRED IN ITS REVIEW OF THE

TOTALITY OF CIRCUMSTANCES AND THE

STANDARD OF VOLUNTARINESS IT APPLIED

IN AFFIRMING THE ADMISSIBILITY OF AN

INCRIMINATING STATEMENT ATTRIBUTED TO

APPELLANT.

A. Record Reflects Inherently Coercive Circumstances

Surrounding Alleged Incriminating Statement.

The constitutional precondition for admissibility of

any alleged confession is that the statement if made, was

one of absolute free will after the defendant had been

fully apprised of his right to remain silent. Even then,

the question in each case is whether a defendant's will was

_ . t 1 • • . , 1, .. — T T , T> t~\\r T T Daf o

O V B i ' D O J T l i e a l L i l t s L X iL ltS i l t s a .J . - 1 - t S ^ k z k a v_-v^axa_ ‘

367 U.S. 433 (1961).

In the instant case deputy Phillips, during appellant's

wait as the jury deliberated his fate during his second

trial, began interrogating Beecher by asking him questions

about what he thought the jury would do0 During this time,

Phillips was well aware that Beecher was represented by

!4/

counsel.

During Phillips testimony at the third trial, Phillips

not only could not remember what happened or the conversation

of the first ten minutes of the interrogation but only

14/ Tr. 1804.

22 -

15/

remembered the statement allegedly uttered by the appellant.

Beecher, on the other hand, not only explicitly remembered

what he said but how deputy Phillips interrogated him and

most importantly, that he never made the statement he is

16/

accused of mating. Whereas, Phillips claims to recall only

this one statement allegedly made by appellant after being

with appellant for approximately forty-five minutes.

Further, as this court has recognized, at the time of

the alleged statement to which Phillips testified, Beecher

had gone through two trials and was awaiting the verdict of

the second trial. >. He was alone with Phillips, who was uniformly

dressed with badge, billy club and gun which certainly created

an intimidating atmosphere which in itself was coercive.

The United States Supreme Court in Miranda v . Arizona, 384 U.S.

436, 86 S. Ct. 102 explicitly stated that before any statement

can be elicited from an accused for purposes of introducing

such statement into evidence, the accused must be given the

Miranda warning. The deputy, fully apprised of the fact that

the appellant was represented by counsel, proceeded to

question the appellant.

15/ Tr. 1105-9.

1§/ Tr. 1084. Also see "Totality" at ___, infra.

23

This court points to the fact that Beecher had

appointed counsel of which Phillips was aware (Slip op. at

14-15). At the same time, this court failed to make

appellant's Sixth Amendment right to counsel under the

United States Constitution little more than an empty right,

if as in this case, Beecher's right to consult with such

counsel was abrogated when he needed such consultation.

Spano v. New York, 360 U.S. 315, 79.S. Ct. 1202 (1959);

Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201, 84 S. Ct. 1199 (1964).

Consequently, appellant’s Sicth Amendment rights have virtually

been repealed if the State of Alabama for the third time per

mits this appellant to be convicted and sentenced on grounds

11/which are constitutionally infirm. Jackson v. Denno, 378

\j/ Since the time of Beecher's incarceration on June 17,

1964, he has been consistently unlawfully interrogated by

law enforcement officers and those secured by the law in

whose custody he has been. In Beecher I and II, which the

United States Supreme Court reversed appellant was subjected

to unlawful interrogation. Also while he was being transferred

on April 6, 1973, from Scottsboro to Moulton for arraignment

(R. 754-55). Sheriff Collins and the district attorney of

Jackson County who are required to adhere to the laws of the

State of Alabama and of the United States again proceeded to

interrogate this hapless appellant. And now deputy Phillips,

an individual sworn to uphold the law, interrogates appellant

when appellant was under his custody and control. Phillips

admits that he knew appellant had appointed counsel; yet, he

proceeded to interrogate anyway (R. 1111). The fruits of this

illegal interrogation were conveniently told to the district

attorney some three years later prior to the third trial

(R. 1115).

24

U.S. 368, 84 S. Ct. 1774 (1964); Escobedo v. Illinois, 378

U.S. 478, 84 S. Ct. 1758 (1964); Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S.

293, 87 S. Ct. 1967 (1967); Glinsey v. Parker, 491 F.2d 338

at 340 (6th Cir. 1974).

This transcript clearly points to the fact that Beecher

was interrogated outside the presence of counsel and without

any Miranda warning. This court has failed to recognize the

importance of that interrogation. Assuming that the form of

interrogation to which Beecher was subjected was not the

usual formal jailhouse interrogation present in Miranda.

Nevertheless, the appellant was interrogated by officer Phillips;

the appellant was in the custody of Phillips and Phillips knew

the appellant had counsel. This fact situation amounts to

in-custody interrogation to which the rule of Miranda un

questionably applies.

It does not matter whether the accused was formally or

Vinformally interrogated as long as he was in the presence of

a police officer and not able to move about unrestrained.

The United States Supreme Court has been explicit in finding

that surreptitious interrogations are as constitutionally

reprehensible as those conducted in the jailhouse. Massiah

v. United States, 377 U.S. 201, 84 S. Ct. 1199 (1964). See

also, United States ex rel O'Connor v. The State of New Jersey,

2 5

405 F .2d 632 (3rd Cir., 1969). Clearly the court must

recognize the inescapable fact that Beecher was not

afforded his federal constitutional rights under the rule

of Massiah. The United States Supreme Court spoke on this

very issue in Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 69, 53 S. Ct.

55 when the court said the accused "requires the guiding

hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against

him." Id. at 69, S. Ct. at 64. Also see United States v.

Bekowies, 432 F.2d 8 (9th Cir., 1970) where the court said

that "a suspect must be warned of his constitutional rights

prior to any custodial interrogation."

In Miranda, as in the instant case, the question presented

dealt with the Fifth Amendment right of the accused to be

free from compulsory self-incrimination and the Sixth

Amendment right of the accused to have the assistance of

counsel.

The United States Supreme Court has made it clear that

with respect to the Fifth Amendment, the conditions under

which the alleged confession was made in no way can be

admitted if it abrogates the involuntariness test. Miranda,

supra; Massiah, supra. It necessarily follows that the

court will not consider the question of voluntariness unless

there is a clear waiver by the accused of his Sixth

26

Amendment right to the assistance of counsel after being

fully apprised of his right to have his attorney.

To be sure, this court does not expect appellant to be

fully apprised of all of his constitutionally protected rights

just because he has been in custody for seven years and has

been through two trials. The court in Miranda made it

explicitly clear that:

"Assessments of the knowledge the defendant

possessed, based on information as to age,

education, intelligence or prior contact

with authorities, can never be more than

speculation; a warning is a clearcut fact.

Id., at 468, 469 S. Ct. at 1625.

The contention that the alleged confession herein was

not the product of formal interrogation by public officers

is not important. The uncontradicted testimony of Phillips

(R. 1142, 1143) here is that the deputy sheriff subtly or

otherwise, commenced the conversation by probing Beecher as

to what disposition the jury was likely to make of the case.

In this situation, psychological coercion obviously could have

been exerted. Miranda, supra, at 466-467, S. Ct. at 1613-1618,

and, therefore, the burden is on the state to affirmatively

show that Beecher knowingly and intelligently waived his Fifth

and Sixth Amendment rights. The state clearly has not met

that burden. Therefore, on the legal history of this case

t'4

27

and the record presently before this Court, appellant urges

this court to find that the alleged statement should have

been suppressed due to the principles laid down in Miranda,

Escobedo, Massiah, supra, and all of the cases subsequent

which have espoused these inescapable fundamental principles

of law.

B. This Court Erred In Not Looking To The Totality Of

The Circumstances In Determining "Voluntariness."

The Supreme Court of the United States has twice

reversed convictions of this appellant on inadmissibility

of confessions. Beecher v. Alabama, 389 U.S. 35, 88 S. Ct.

189 (1967); Beecher v. Alabama, 408 U.S. 234, 92 S. Ct. 2282

(1972). Both times this appellant was tried, convicted,

sentenced and given the death penalty as a result of con

fessions illegally obtained from the appellant and introduced

by the State. Twice those convictions have been overturned.

And now a third time, the State is trying to convict appellant

on a statement he is alleged to have made to a deputy while

appellant was awaiting the jury's decision in his second

trial, a trial in which he was convicted and sentenced to

death. Subsequently, that conviction was later reversed by

the Supreme Court of the United States. Beecher v. Alabama,

28

408 U.S. 234, 92 S. Ct. 2282 (1972).

The statement is alleged to have been made to a deputy

Kenneth Phillips, while Phillips and Beecher sat alone while

the jury deliberated during the course of his second trial.

This statement was alleged to have been made to a man who,

18/

in 1964, was part of the massive manhunt for appellant and

at the time of the alleged confession, he was a deputy guarding

appellant as appellant awaited for the jury to finish deliber-

19/

ating. Consequently, on the basis of these facts, it is

impossible for Phillips to be an impartial observer.

Phillips testified that Beecher looked into the ceiling

-r* i cl * , , T*r*-i rl o f 0 3 - 0 C ’t2TILO ^ 2 2T T 1 rp

20/

a guilty man. I don’t deserve to walk the streets." Beecher

is alleged to have confessed to a crime he did not commit.

Appellant had just gone through a trial in which he had

vigorously denied committing the crime he has been accused of

committing. It appears highly improbable that this appellant,

in the midst of a second trial for the same offense, having

been incarcerated for seven years, one case reversed on a

confession issue, with lawyers who during his second trial

w R. 1153.

w R. 1104, 1144

2 0 / R. 1104, 1144

- 29 -

who had unsuccessfully opposed an inadmissible confession,

admit to an officer guarding him that he had committed the

crime with which he was charged. This Court should take

notice that this appellant has twice been convicted and

sentenced to death by the State of Alabama unconstitutionally

by means of "confessions." The totality of circumstances

surrounding Beecher I, II and now III makes any incriminating

statement attributed to appellant out of the presence of

counsel while alone with any law enforcement officer, to be

extremely suspect of illegality and unconstitutionality. In

light of the past history of this case, the State has a tre

mendous Durden to snow voluntariness which on the faces

surrounding this "confession," it failed to carry. This

alleged statement clearly should have been ruled inadmissible.

On voir dire and in the presence of the jury, Phillips

emphatically stated that he does not remember the first ten

minutes of the conversation, and only remembers the statement

21/allegedly made by appellant. Holding this alleged statement

"voluntary" and admissible makes mockery of the Fifth Amendment

rights of this appellant. Phillips is so uncertain as to the

total surroundings of the questioning as to have developed

2j/ Tr. 1105-09.

30

22/

amnesia for the first ten minutes of the conversation. It

is revealing that with amazing clarity of thought he remembers

the alleged "confession" which he repeats to the prosecutor

after the reversal in Beecher II. Yet he cannot remember the

circumstances surrounding such an important statement as the

one allegedly made by the appellant or anything else that

was said. Be mindful that Phillips is a deputy and was so

at this time which cast an additional burden on him, not only

to report the total circumstances of the interrogation of

appellant, but to report it fairly and timely. Justice demands

a more accurate accounting by Phillips if his testimony is to

so 1 pyprif "fro Ico ‘tl'io ovsrridin.0, fcictoir in. ilic conviction

23/

of appellant.

This Court must require and justice demands that on

review this Court hold the admission or the alleged "confession"

was reversible error, and violative of appellant's Fifth

Amendment rights under the Constitution of the United States.

There should be proof beyond a reasonable doubt and to a

moral certainty that appellant is guilty of the crime with

which he is charged. As one makes a straightforward

22/ Tr. 1105-09.

23/ See Appendix A.

- 31 -

assessment of the factual circumstances surrounding this

case, it becomes clear that this is another of a series of

attempts to convict Beecher "out of his own mouth." Miranda,

supra.

On the evidence presented to this Court in view of the

totality of the circumstances, and the testimony of both

Phillips and the appellant on voir dire in the record of this

case, appellant urges this Court to view this case from a

total perspective as it is obligated to do. We urge the

Court to read appellant's testimony on voir dire in the

24/record. Appellant Beecher expressly remembered not making

the alleged statement he is accused of making, but remembers

25/

the entire interrogation by Phillips.

The state has not proven by any means that appellant

made the statement and if the state assumed that the state

ment was made, this Court must look to the "totality of the

circumstances" surrounding the confession. Spano v. New York,

360 U.S. 315, 79 S. Ct. 1202, Tikes v. Alabama, 352 U.S. 191,

77 S. Ct. 281. Under these tests, Beecher's conviction

cannot stand.

Appellant contends that a review of the totality of the

24/ Tr. 1083-86.

2_y Tr. 1083-86.

- 32 -

circumstances surrounding the "alleged confession" and of

the previous Beecher cases would mandate that it was

reversible error for the trial court to rule it admissible.

V>

33

IV

THIS COURT'S FINDING THAT THE RECORD

DOES NOT SHOW THE CONTEXT OF THE

DISTRICT ATTORNEY'S STATEMENT THAT

"NO ONE TOOK THE STAND TO DENY IT"

WAS ERRONEOUS.

On the motion for a mistrial, the trial court stated

that it would give each counsel an opportunity to make a

statement concerning the district attorney's alleged comment

26/on the failure of the defendant to take the stand. (Tr.

1201).

That the comment "No one took the stand to deny it"

was made by the district attorney in referring to the

testimony of Ken Phillips is uncontradicted and undenied.

(Tr. 1201, 1202). Neither does appellee's brief contend

otherwise (Brief for Appellees, pp. 18, 19). For this Court

to conclude under these circumstances that there is no basis

on which to make a finding as to the context of the admitted

statement is to utterly disregard the statement of counsel who

is a sworn officer of the court. Moreover, the trial court's

direct statement that it would accept statements from counsel

on the hearing of the motion, placed such statements on a par

with the testimony of a witness. Hence, it could be concluded

that the context of the prosecutor's comment was shown to be

in reference to the testimony of Phillips.

26/ It must be noted that appellant's counsel were under the

impression that the reporter was taking down all argument. It

was only on the hearing of the motion for a mistrial that they

were made aware that the argument was not being recorded

(Tr. 1199-1201).

34

A balancing of the equities and fairness would suggest

that where the vital interests of a defendant are concerned,

doubts should be resolved in the defendant's favor and a

new trial granted.

It is clear from this record that appellant was the only

one who could take the stand to deny Phillips' testimony;

and a finding that the remark was in reference to Phillips'

testimony requires that appellant's conviction be reversed

and a new trial ordered. Street v. State, 266 Ala. 289,

96 So.2d 686 (1957).

W

35

V.

IT WAS REVERSIBLE ERROR FOR THE TRIAL COURT

TO ADMIT INTO EVIDENCE TESTIMONY ON "TRACKING"

WHICH DID NOT COMPLY WITH THE PROPER STANDARD

FOR ADMISSIBILITY.

Wilson, the parolee who testified at appellant's trial

did not train the dogs, which he testified he trailed.

Instead, they were trained by someone else (Tr. 911). He

only walked behind the dogs and did not know how the dogs

were trained. On occasion, he would take a man out into the

woods and later take the dogs there and begin tracking the

person. In order for the dogs to track someone, the dogs

must first be given something that contains the scent of

the person they are tracking. Gallant v. State, 167 Ala.

60, 52 So. 739 (1910); Allen v. 5 Late, Ala. App. 22S; 62

So. 971 (1913).

In the instant case, at no time were the dogs given the

scent of Beecher (Tr. 975-77). The dogs tracked from a shoe

print which was supposed to have been that of appellant.

Later during the day of the escape, William Wilson brought

dogs in from Atmore Prison (R. 818) and began tracking from

the area from which appellant escaped — never receiving the

27/

scent of appellant and never catching appellant.

27/ Claude Sisk, the highway convict guard during the time

that Beecher escaped, emphatically stated that there was no

way by which Beecher could have firrived at the Chisenall house

by the time he arrived at the house after discovering Beecher's

escape (Tr. 854-855). Further, at the time when he arrived at

the Chisenall house, shortly after Beecher's escape and before

which time Beecher could not have arrived at the house, no one

was present at the Chisenall home (R. 852-853).

36

Consequently, some time later, after the dogs left

the barn, they went up the side of a mountain, stopping at

a deserted log cabin where they discovered a man's white

undershirt. This was not Beecher’s shirt, because the record

shows he had his undershirt on when he was shot three days

later in another state (R. 268-69). The evidence has yet

to establish that the dogs were tracking appellant. The

state offered no evidence as to whose "undershirt" was found

nor was it offered in evidence. It is not possible for the

tracks to have been appellant's if the dogs were trained to

trail the scent or track of the prints shown them behind the

barn. The dogs went to a cabin where they, in effect, "treed"

an undershirt. The undershirt was not appellant's. There

fore it is not possible for the dogs to have been trailing

appellant.

Thereafter, at no point in time, did the dogs ever show

any signs of following the same trail. The dogs just picked

up a trail and began following it into a sage field (R. 980).

At this point, the dogs were scattered by a helicopter and

thereafter not only did the dogs lose the trail they were

following, but lost all sense of perspective because it took

approximately an hour to gather the dogs (R. 980). Thereafter,

the dogs picked up an anonymous trail which the dogs followed

to a strip mining pit area where, approximately 75 people

were gathered (R. 980-81). Wilson clearly testified that:

"After having lost the original scent for

a period of time, oh, thirty minutes to an

hour, they would if they ran across a fresh

scent of another person, they would probably

run it." (R. 983) .

After the dogs had been gathered, a new scent was picked up.

37

5

Clearly, this evidence should have been ruled inadmissible

because there was nothing which survives even a cursory

analysis. The entire testimony simply has no probative

value and should have been held inadmissible. Richardson

v. State, 41 So. 82, 145 Ala. 46 (1906). This would hold

true even if Wilson had trained the dogs himself. There is

no evidence that the alleged dogs were trained to track human

beings; there is evidence that Mr. Wilson did not train them.

A fundamental bases required for such testimony simply was

not established and it was prejudicial error to admit it.

Little v. State, 39 So. 674, 145 Ala. 662 (1905).

Finally, the dogs were placed on a truck and taken to a

nearby river where a person was supposed to have been seen

(R. 981-82). At this point, the dogs definitely had no scent

28/which resulted in one dog swimming into the river to a stump.

Again this is evidence that the dogs were not trailing

appellant from the outset. Hereafter, the dogs never picked

up another scent even after crossing the river which clearly

shows that at no point and time can appellant be placed at

or near the scene of the crime as the state would have this

29/Court be1ieve.

23/ R. 983.

?g/ Interestingly enough, appellant brings to the Court's

attention that this "evidence" of tracking was presented by

the State for the first time in this, appellant's third trial.

38

The state would have this honorable Court believe

that Mr. Sisk who was the highway guard did not have the

ability to judge distance and time. Sisk emphatically stated

that Beecher did not have time to reach the chisenall home

from the time of his escape to the time of the Sisk arrival,

and that Mrs. Chisenall was not at home, when he, Sisk,

arrived (R. 852-53).

Yet, the state would have this Court believe the wild

goose chase of five dogs that are not of a particular pedigree

over that of a person who at the outset was in extreme

proximity to appellant. Dogs may be able to trail a track,

but they cannot judge distances and equate that distance

with time and determine the amount of time it would take one

to travel that distance on foot. Mi.. Sj.sk could cuiu he

unqualifiedly stated that there was no way in which appellant

30/could have arrived at the victim's home before Sisk did.

Under the law of the State of Alabama for such testimony

as Mr. Wilson's to be admissible, he must be qualified to track

humans with the dogs, and must have trained the dogs.

Richardson, supra. Or, at a minimum, the dogs must have been

used by the witness for two years and that the witness must

have at least ten years experience in handling bloodhounds

and that will carry the burden of qualification. Burks v.

State, 200 So. 418, 240 Ala. 587. Wilson had only worked

with the dogs for approximately one year (Tr. 910-11).

Therefore, it is respectfully submitted that any evidence

presented by the state from the tracking of the bloodhounds

to try and place appellant at the scene or in the vicinity

30/ R. 854-55. 39

of the crime is not only inadmissible, but does not and

cannot carry the burden of proof that is so necessary to

make the state's case. Hence, appellant contends the

admissibility of Wilson's testimony at trial was prejudicial

error and requires that appellant's conviction be overruled.

to

40

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated throughout this petition for

Rehearing and Brief in support thereof, appellant Johnny Daniel

Beecher prays that this Court will reverse his unlawful

conviction; and remand this cause for a new trial.

Respectfully submitted,

U. W. demon

ADAMS, BAKER, & CLEMON

Suite 1600 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

ELAINE R. JONES

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

W

-41-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 15th day of October,

1974, I have served copies of the foregoing Brief in Support

of Petition for Rehearing upon the following persons by

mailing to each, postage prepaid, a copy of same:

John T. Black, District Attorney

Ninth Judicial circuit

Centre, Alabama

William Baxley, Attorney General

State of Alabama

Montgomery, Alabama

V Attorney for Appellant

APPENDIX A

I

i .

1

V j1 ■' r'

7

J iL jli2 j

"M y country, may she ever be right, but, right or wrong, my country." - ccm m oo oreStephendecatur

DECATUR, ALABAMA, 35301, FRID aY, JUNE 22,1973 U

!>hdndM2O

HX

>

I T

i g e e e m e E 3

By TOMMY STEVENSON

MOULTON — A member of the jury

which sentenced Johnny Daniel Beecher

to life imprisonment for the 1964 murder

of Mrs. Martha Jane Chisenall said today

the disputed testimony of a Cherokee

■ County deputy sheriff was a key, but not

all-important, factor in the jury’s

decision.Ken Phillips, who was guarding

, Beecher while the jury was deliberating

in Beecher’s second trial in the case,

testified Beecher told him “I’m scared of

the electric chair because I’m guilty.”

Lawrence County juryman Rayford

W. Green, a Town Creek industrial

worker, said the defense did nothmg to

convincingly disprove Phillips testimony

and that “was what lacked in the opinion

that Beecher was guilty.

“We had some questions when we

j went back to deliberate and felt like the

state should have presented some mare

witnesses,” Green said, but the

testimony of Phillips was definite/ a

factor in our decision.

“We wondered why the defense did

not do much to try and disprove what he

said. Wre also wondered why the defense

did not call any witnesses when it ct me

their turn.”What Green did not know was tiat,

while Phillips was being questioned oi t of

the .presence of the seven-man, five-

woman jury on a defense motion to

disallow his testimony, it had been argued

that the alleged confession was in

violation of several U.S. Supreme Court

decisions on the rights of defendants,

including decisions in two previous

Beecher trials.

The three-member defense team, led

by Birmingham Attorney U. W. Clemon,

argued that the confession Phillips said

Beecher made was similar to the

confessions entered into the first two

trials, in 1S64 and 1969, which caused the

overturning of the guilty decisions in both

trials on the grounds of “gross coercion.”

Clemon contended that any

confession made by the defendant without

the presence of a lawyer or without prior

warnings as to the defendant’s rights, was

inadmissable under guidelines set by the

courts in such landmark decisions as the

Miranda and Escobedo cases.

The prosecution handled by 9th .

Judicial Circuit Court Dist. Atty. John T.

Black of Ft. Payne, claimed that since the

alleged confession was completely

voluntary and came as a result of no

prodding by Phillips, it should be allowed.

Tbe defense also contested Phillips’s'

claim that the confession was voluntary

and put Beecher on the stand during the

See BEECHER On Page A-5

)

[NOTE:

Article in support of Motion

for New Trial]

Beecher

(Continued from Page 1)

hearing to contradict Phillips’s

testimony.

Beecher said that what he had really

said was “if the people of Cherokee

County have the same opinions about me

as the people of .Jackson County (where

the crime took place and where the first

trial was), then they’ll find me guilty.”

Beecher further testified that his

statement came in reply to direct

questioning by Phillips. The testimony by

Beecher was his second appearance on

the stand in the trial, but both

appearances came during voire dire

hearings out of the presence of the jury.Wh'CI'l AA at' rr o n

County and associated with the case from

its beginning, ruled that Phillips could

testify before the jury on the alleged

confession, defense lawyer Thomas

Divens,of New Orleans, said, of Powell,

“I can’t believe it; he’s just asking for

! another trial. The courts will never let it

stand. It’s like he wants to try it again.”

Immediately after the jury

announced its decision shortly before 3

p.m. Thursday, demon served notice of

another appeal. And that appeal will

likely center around Powell’s decision to

allow Phillips’s testimony as well an

numerous exceptions taken to Powell’s

rulings throughout the trial.

Thursday’s concluding proceedings in

the case were taken up largely by the

summations of both the defense and the

prosecution after Clemon announced the

defense would call no witnesses.

Black, in making the case for the

prosecution, emphasized the confession

allegedly made to Phillips and the

i material evidence in the case. He said

I that state bloodhounds had traced

Beecher from the point where he escaped*

from a prison work gang, to the Chisenall

home, and into the mountains behind the

home where Mrs. Chisenall’s body was

found.

Black said the bindings around Mrs.

1 Chisenall’s hands and feet were made of

material similar to that of Beecher’s

prison shirt, and that the belt around her

neck, with which she was strangled was of

---------!---------- -----------

the type issued to inmates.

The defense countered with the

argument that the trail the dogs traced

was not necessarily that of Beecher and

that the testimony of Phillips was

politically motivated because he had a lot

to gain in his profession by contributing to

the conviction of a “famous man” like

Beecher.

The defense also pointed to the

testimony of Beecher’s work gang guard.

Claude Sisk, who said there was not

enough time for Beecher to get to the

Chisenalt home and ahdnot Mrs Chisenall

before Sisk arrived in his truck.

The summations and the charge by

Judge Powell occupied all of the

morning’s proceedings and it was not

until lunch that the jury began

deliberations on the second floor of the 1

Lawrence County courthouse.

Green said that the deliberations

were relaxed and that he felt “we all

entered into the deliberations with open

minds.

“Everybody had a hand in the

discussions and there was no pressure on

anyone to go along with the crowd,”

Green said.

“First of all we went over all the

evidence very carefully and if there was

any doubt on the part of anyone, we would

stop and talk over whatever they were

wondering about.”

Green said that the testimony of Sisk,

considered the most convincing evidence

for the defense, was dismissed because of

the time element.

“Nine years is a long time and we

didn’t think Sisk’s memory of just how

long it took him to get to the house would

be that good,” Green said.

The jury took less than two hours in’

arriving at its devision and sentencing

Beecher to the maximum sentence.

Beecher’s two previous conviction;

resulted in death sentences, but due to the "|"

recent Supreme Court decision- life

imprisonment is now the most severe

penalty possible.

APPENDIX B

v

APPENDIX

r V / \ A A / V ' :i : i 7 r ^ . ^ ^ r V > T / :'f | : i j j f ; \ >

Ay' /-V V' V V /N/ r ^

Hanwvffle, i b t a , Tuesday, March 13, 1973

❖ i f f t

,.V

The T ire s Sccltsboro Bureau

CENTRE — Circuit Judge

Newton 15. Powell of Decatur

was expected to grant ̂ a

change of venue this morning

in the third murder trial ot

Johnny D. Beecher.

rowel! yesterday released

SO jurors who were challenged

by the defense, but last night

ordered t'ne remaining jurors

on the panel of 53 to return

and directed Sheriff Mac Gar

rett to deliver summonses to

additional potential jurors.

Cherokee County Circuit

Court Clerk Fred Green said

todav that Powell told him

last night that after the jurors

reported today, he was going

to grant the defense’s request

for a change of venue. Ac

cording to one unverified re

port, the trial will he moved

to adjoining DeKaib County.

Beecher has been convicted

twice of the June, 1361 rape-

slaving of Mrs. Martha Jane

Chisenhali. a young white

woman who resided near Ste

ven on in Jack.cn County. In

;• \ \ I- aether was given

The TJ. S. Supreme Court

reversed both convictions, and

in so doing, threw out sepa

rate confessions attributed to

Beecher, who was a 32-year-

old' convicted rapist with a

record of four escapes when

he fled a Camp Scottsboro

work detail on the day Mrs.

Chisenhali was abducted.

U. W. demon of Birming

ham, a member of a team of

attorneys hired by the

Turn To Page 4

4

Beecher

Continued From Page One

NAACP's Legal Defense Fund

tc represent Beecher in his

third murder trial, yesterday

questioned individually and at

length the 56 persons who

reported as prospective jurors

i:i the trial.

Under interrogation by de

mon, the 30 jurors who were

excused by the court gave an

extensive range of answers.

Vhe jurors offered these opin

ions under questioning:

— Since Beecher has twice

been found guilty of the min

der, he is “either guilty or

probably guilty” of that of-

icnsc.1 _ “He must have had

something to do with case or

he wouldn’t have been tried

twice.” . .— “Those two convictions

would he in the back of my

mind during the trial of the

C3S6.’*_ “The grand jury would

not have indicted him again if

they didn’t have some evi

dence.” ._ “I think it is up tc the

defense to present evidence

that he is not guilty.”

_ “I go along with the 21

jurors (in the two piev.ous

trials) who have said he is

guilty.”

_ “I believe he is guilty