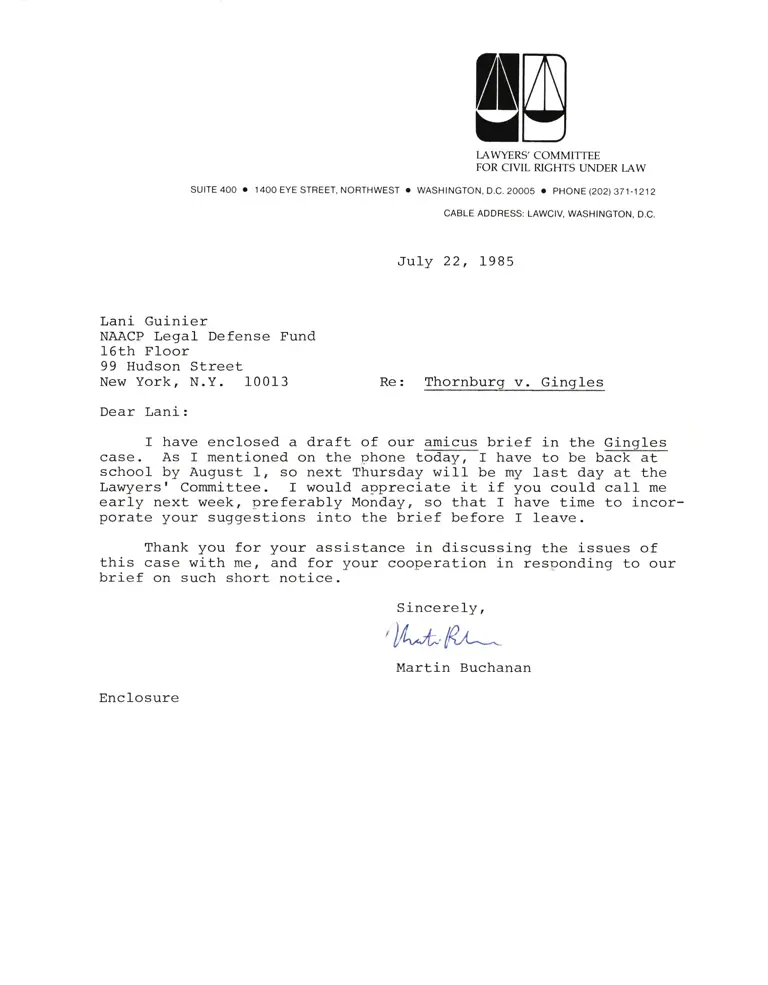

Correspondence from Buchanan to Guinier; Draft of Amicus Brief; Envelope

Working File

July 22, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Correspondence from Buchanan to Guinier; Draft of Amicus Brief; Envelope, 1985. 02938f00-e092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6f052b8c-1f83-44aa-86df-628a4ed1c205/correspondence-from-buchanan-to-guinier-draft-of-amicus-brief-envelope. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

T.AWYERS' COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

sulrE 4o0 . 14oo EYE srREET, NORTHWEST . WASHINGTON, D.c.2ooos . pHoNE (2o2,)sr1-1212

CABLE ADDRESS: LAWCIV, WASHINGTON, D.C.

July 22, 1985

Dear Lani:

f have enclosed a draft of our amicus brief in the Gingles

caSe.AsImentionedonthephonetod,ay,rhavetobebffi

school by August I, so next Thursday will be my last day at the

Lawyers' Committee. I would appreciate it if you could call me

early next week, preferably Mondayr so that I have time to incor-

porate your suggestions into the brief before I leave.

Thank you for your assistance in discussing the issues of

this case with me, and for your cooperation in responding to our

brief on such short notice.

Lani Guinier

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

16th F loor

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

Enclosure

Re: Thornburg v. Gingles

Sincerely,

'l/*b,R 4*.

Martin Buchanan

I

llr,

TABLE OF' CONTENTS

suMMARy op ARGUMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

r. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERTY CONCLUDED

THAT THE TOTALITY OF CIRCUMSTANCES

DEMONSTRATED AN IMPERMISSIBLE DILUTION

OF MINORITY VOTI}iG STREI{GTH, AND ITS

ANALYSIS OF EACH OF TEE RELEVANT FACTORS

WAS CONSISTENT WITH THE VOf ING RIGIITS

AcT AMENDMENTS OF 1982 . . . r . . . . . r . . .

A. Congress Did Not Intend that the

Election of a Few Black Candidates

Would Prevent a Finding of fmpermis-

sible Vote Dllution lvhere the Aggre-

gate of Circumstances Demonstrated

Inequal ity of Opportunity to

Participate in the PoIitical Process . . . . .

B. The District Court Properly Evaluated

the Uncontradicted Evidence of RaciaI

Bloc Voting to Determine the Extent

to which Voting was Racially Polarized . . . .

II. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT RQUIRE GUARAN-

TEED ELECTION OF BLACK LEGISLATORS IN

NUMBERS EQ UAL TO THE PROPORTION OF BLACKS

IN NORIII CAROLINAIS POPULATION . t . . .

CONCLUSION . . . r . . . . . . . . . . . . r . r . . . . .

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The contentions raised by apperrants in this case present

several questions concerning the standards mandated by Congress

for claims arising under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

Amendments of 1982. These contentions are basea on mischarac-

terizations of the district court,s legal analysis which are

identical to arguments explicitly rejected by Congress, and which

seriously misconstrue the object of the amended Voting Rights

Act. The district court properly conducted an exhaustive

investigation into the interaction of historical, political, and

sociological factors with the electoral structure at issue to

conclude that2 corlsidering the totality of circumstances, blacks

in the challenged multi-member districts in North Carolina did

not have an equal opportunity to participate in the political

process or. to elect candidates of their choice.

Appellantsr assertion that the success of a few black

candidates in 1982 precluded a conclusion of impermissible vote

dilution or a finding of racially polarized voting evinces a

fundamental misunderstanding of the structure of amended Section

2 and its requirements. The district court's determination that

these achievements h,ere unusual was not clearly erroneous given

the uncontradicted expert testimony at trial, and the court

properly weighed the 1982 elections as one relevant factor in the

totality of circumstances.

The district court also properly evaluated the extent to

which voting vras racially polarized in the challenged districts.

Appellantsr attempt to redefine the criteria for judicial

analysis of racial polarLzation effectively reintroduces an

intent requirement into Section 2 litigationr a result undeniably

contrary to the mandate of the 1982 amendments. Furthermore,

appellants confuse the issues of racial bloc voting and 6lack

electoral success, erroneously elevating each to ; status above

that of the other elements of a Section 2 claim.

Appellants mistakenly suggest that the district court

adopted a proportional representation standard for vote dilution

cases. There is nothing in the courtt s opinion to support such a

contention; nor is there any evidence to support the allegation

that, the court confused effective representation with representa-

tion by a member of one's o$rn race. The district court expl ic-

itly disavowed both of these mischaracterizations of its opinion.

fn sum, appellantsr claims represent an endeavor to revive

in this Court a debate which was resolved by Congress when it

passed the voting Rights Act Amendments of L982. Congress has

unequivocably rejected the argument that consideration of the

extent to which minority groups have been elected is necessarily

equivalent to a proportional representation requirement. It has

also unquestionably indicated its disapproval of any attempt to

read an intent requirement into its legislation. rinally,

Congress has expl icitly indicated that none of the elements of

Section 2 claims are necessarily to be accorded greater weight

than any of the others. Acceptance of appellants' arguments

would contravene the intent of Congress in enacting the Voting

Rights Act Amendments

abil ity of minorities

that Act.

L982, and would seriously erode the

enforce the rights granted them under

of

to

A RG UMENT

r. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY CONCLUDED THAT THE

TOTALITY OF CIRCUMSTANCES DEMONSTRATED AI{ I}F

PERMISSIBLE DILUTION OP MINORITY VOTING STRElilGTIT,

AND ITS ANALYSIS OF EACH OF THE RELEVAMT FACTORS

WAS CONSISTENT WITH THE VOTIIre RIGIITS ACT AMEUO-

MENTS OF 1982.

Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act Amendments of l-9B2

primarily in response to this courtrs ruling in citv of Mobite

v. Boldent 446 U.S. 55 (1ggo). rt is undisputed that the

principal objective of this legislation was to provide a private

remedy for electoral schemes which denied minorities an equal

opportunity to participate in the political process, but which

courd not be shown to have been motivated by aiscriminatory

intent. rn approving this legisration, congress made it plain

that it meant to return to the legal standards which governed

constitutional vote dilution claims prior to Mobile, with

specif ic ref erence to @, 412 U. S. 755 (1973),

and the federal appellate court cases which followed Ehi-@,

including zimmer v. McKeithen, 495 F.2d l2g7 (5th cir. 1973) (en

banc), aff'd sub nom. East carroll parish schoor Board v.

Marsha11r 424 U.S. 535 (1976). S. Rep. No. 4l-7t 97th Cong.r 2d

Sess. at 15 [hereinafter cited as S. Rep. ]. SpecificaIly,

congress mandated that the focus of inqui ry in section 2 vote

dilution craims be on the question of whether, ,'based on the

totality of circumstancssr it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or election in the State or

political subdivision are not equally open to participationn by

minority grouPs. 42 U.S.C. S 1973. The Senate Report on the

amen&nents specified seven factors on which plaintiffs typically

rely to estabLish such a vlolatioDr a list which Yas

nderived

from the analytical framework used by the Supreme Court in Eh;lls,

as articulated in Z;!gSSI. n S. Rep. aL 28 n.113.1

The district court in this case properly evaluated the

plaintiffs' claims under the lega1 standards promulgated by

Congress and followed by appellate courts in constitutional cases

bef ore Ug.b-LI-g. Since appellants do not contend that the courtrs

analysis of any of the individual factors specified in Ehose

cases was clearly erroneous under Fed. R. Civ. P.52(a), it is

unnecessary to review at Iength the courtr s extensive considera-

tion of the abundant evidence on each f actor.2 In sulllr the

district c6urt's factual findings amply support the ultimate

conclusion that blacks in North Carolina did not have an equal

Irh" list of f actors included in the Senate Report, *s

S. Rep. at 28r 29, can be found in the appellants' brief, and is

therefore not reproduced here. See Appellantsr Brief at 21 n.9.

2appellants do raise questions about several of the district

court's factual findings which they did not address in their

jurisdictional statement. See Appellants' Brief aE 25 (history

of official discrimination), 27 (minority vote requirement), 28

(socioeconomics), 30 (racial appeals) ' 32 (responsiveness), 34

(legitimate state policy). However, they do not seriously

contend that any of these findings are clearly erroneous.

Rather, the argument with respect to each of these factors seems

to be that they are all legally irrelevant in the face of minimal

minority electoral success. Since the same basic claim underlies

all of the appellantsr arguments, it would be unnecessarily

repetitive to consider each factor separately in this brief.

opportunity to participate in the political process in that

state.

A. Congress Did Not fntend That the Election

of a Few Black Candidates Would prevent a

Finding of Impermissible Vote Dilution

Where the Aggregate of Circumstances Demon-

strated Inequal ity of Opportunity to

Participate in the PoIitical Process.

Though appellants do not contest the sufficiencry of evidence

to support any of the district court's factual findings, they do

claim to dispute the legal standards under which the factors

specified in the Senate Report were analyzedr3 particularly

3rh" Department of Jus

with the district courtrs I

tice, also purporting to take issue

egal analysis, argues that it is

vested with othe primary responsibility for enforcing the Voting

Rights Act and thus has a substantial interest in ensuring that

the Act is construed in a manner that advances, rather than

impedes, its objectives." Br. {or U.S. at 1. While it is Erue

that nthis Court shows great deference to the interpretation

given the statute by the officers or agency charged with its

administration,r rtdall v. Tal IJllElIt, 380 U. S. I | 15 (1955) , it is

not in fact the case that the Attorney General has primary

responsibility for administering Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act, since that authoriEy is vested exclusively in the federal

courts, 42 U.S.C. S 1973j(f), and the bulk of Section 2 litiga-

tion is initiated by private plaintiffs. This Court has in the

past shown deference to the Attorney Generalrs determinations

under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, since the United States

is statutorily charged with administration of that Section. 42

U.S.C. S 1973c. See e.q., Nat'1 Assrn for the Advancement of

Colored People v. Hampton County Election Commr n,

-U.

S.

-,

53 U.S.L.W. 4207, 4210t n.29 (U.S. Feb. 27, 1985); Dougherty

County Bd. of Educ. v. White,439 U.S.32,39-40 (1978); United

States v. Sheffield Bd. of Comm'rs, 435 U.s.110,131-32 (1978)i

Perkins v. Matther.rs , 400 U. S. 379, 391 (1971) . These cases were

also premised on "the extensive role . . Attorney General

lKatzenbachl played in drafting the statute and explaining its

operation Eo Congr€sS. rr

Commrrsr 435 U.S. at 131; see also S. Rep. at L7 n.51. Since the

current Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights opposed

enactment of the 1982 amendrnents to Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, deference to his interpretation of those amendments

is inappropriate. See 1 Voting Riqhts Act: Hearings on S. 53 et

a'l Before the Srrheomm- on the Constitution of the Senate

minority electoral success and racial bloc voting. Appellants

contend first that the election of some blacks to office in the

challenged districts Proves that the use of multi-member dis-

tricts did not result in denial of equal opportunity for minori-

ties to participate in the political Process. APPellantsr Brief

at 24. This argument is contrary to gongress' clearly expressed

legislative intent and inconsistent with the objectives of the

Voting Rights Act Amendrnents of 1982. Since the appellants have

failed to raise any genuine legaI issues regarding the district

courtrs treatment of minority electoral success, its findings are

properly evaluated under Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a)rs clearly errone-

ous standard.

The text of the Senate Report itself expl icitly disavows the

proposition that the success of a few black candidates will

foreclose the possibility of

S. Rep. at 29 n.115 (quoting

a finding of racial vote dilution.

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297t

1307 (5th Cir. 1973)).4 This statement of legislative intent is

Comm. on the Judiciary, 97 th CoD9. r 2d Sess. 1655-1850 (1982)

tStatemenl of William gradford neynolds) [hereinafter cited as

Senate Hearings I .

4fh" Department of Justice argues in its brief that the

Senage Report ncannot be taken as determinative on all counts, n

and that tne statements of Senator DoIe must instead "be given

particular weight. " Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Supporting Appellants at 8 n.!2, 24 n.49 [hereinafter cited as

er.-for U.S.J. This is a curious argument to make given that the

first sentence of Senator DoIers Additional Views itself states:

oThe Committee Report is an accurate statement of the intent of

S. 1992r ds reported by the Committee. r S. Rep. at 193 (Addi-

tional Views of Senator DoIe). See also S. Rep. at 199 (Supp1e-

mental Views of Senator Grassleyr cosponsor of Dole compromise

amendment) (nI am wholly satisfied with the bill as reported by

the Committee and I concur with the interpretation of this action

consistent with the general language of the statute itself, which

addresses inequality of opportunity to participate in the

political process, and is not limited to absolute denial of

participation. Furthermore, the disclaimer in Section 2 explic-

itly states that "[t]he extent to which members of a protected

class have been elected to office is rone

"ir"u*"iance'

which may

be considered. . . . " 42 U.S.C. S 1973. This language

obrviously contemplates the possibility of successful vote

dilution claims nothwithstanding limited minority victories at

the polls. As the Zimmer court stated quite clearly: nwe shal1

continue to require an independent consideration of the record."

485 F.2d at 1307, quoted in S. Rep. at 29 n.115.

Appellantst insistence that the courtts analysis of minority

electoral Success is enough in itself to require reversal is

misguided. The question is whether the courtr s independent

consideration of the totality of circumstancesr including as one

in the Committee Report.n). It is hard to imagine why the Senate

Report should not be regarded as an authoritative pronouncement

of-Iegislative intent, since it has been endorsed by the supi

porteis of the original billr ds well as by the proponents of the

lompromise amendment. Furthermore, it is well-established that

"reports of committees of lthe ] Ilouse or Senate . . : maY be

regirded as an exposition of the legislative intent in a case

where otherwise the meaning of a statute is obscure. " DupIex

Printinq Press Co. v. Deeringt 254 U.S. 443t 474 (1920). In

fact, it is the governmentr s extensive reI iance on the statements

of witnesses before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary which

is misplaced. Sg3 Ernst & Ernst v. Ilochfelder, 425 U.S. 185, 203

n.24 (fgZe) ('Remarks of this kind made in the course of legisla-

tive debate or hearings other than by persons responsible for the

preparation or the drafting of a biI1, are entitled to litt1e

weiifrt.")i McCauqhn v. Hershey Chocolate Co.,283 U.S. 488,

493-94 (1930) (statements "made to committees of Congress

. . . are without weight in the interpretation of a statute.")

factor the recent success of some black candidates, was clearly

erroneous. The contention that an incorrect leqal standard was

emPloyed to analyze the Iink between minority electoral success

and the ultimate issue of unequal access is plainly at odds with

this court's decision in Roqers v. Lodqe , 458 U. S. 513 (1982) .

In Rogers, this court concluded that, under the constitutional

standard for vote dilution claims, the clearly erroneous test

applies to the ultimate finding of purposeful discriminationr Els

well as to each of the subsidiary findings of fact necessary to

support the conclusion of intentional discrimination.5 ft would

be odd indeed if the inference from the Zimmer factors to a

conclusion of discriminatory intent vrere governed by

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a), but the inference from those same factors

to a conclusion of discriminatory results was not.5 Thus, the

5rh" holding in Roqers lras consistent with pre-Mobile

federal appellate court cases on which Congress relied in

amending the Voting Rights Act in L982. S9-9, e.q., Nevett

v. Sidest 571 F.2d 209t 226, 228 (5th Cir. 1978) cert. denied,

446 U.S. 951 (1980) ("[T]he district court's determinations under

the zimmer criteria will stand, if supported by sufficient

evidence, unless clearly erroneous. E'ed.R.C.P. 52(a).n The

aggregate of Zimmer factors nis a factual issue that must be

resolved by the district court. . . n)i Paiqe v. Grayr 538 F.2d

1108, 11Ll (5th Cir. 1976) ('The weighing of Ithe Zimmer] factors

is ordinarily a trial court function which we wiIl not undertake

initially unless the record is so clear as to permit of only one

resolution."). See also, Cross v. Baxter, 604 F.2d 875t 879 (5th

Cir. L979)i Hendrix v. Joseph, 559 F.2d 1265,1268 (5th Cir.

1977)i David v. Garrison, 553 E.2d 923,930 (5th Cir. 1977)i

Gilbert v. Sterrett, 509 F.2d 1389' 1393 (5th Cir. 1975), cert.

denied 423 U.S. 951 (1975).

5rt would be particularly odd given the fact that, in some

equal protection cases, a stark pattern of discriminatory impact

can itself be determinative as to discriminatory intent. See,

e.g., Arlinqton Heights Metropolitan Hous. Dev. Corp. | 429

U.S. 252, 266 (1977) ('sometimes a clear pattern, unexplainable

fifth Circuit correctly concluded in Velasquez v. Abilenet 725

F.2d 1017, ].02l (5th Cir. 1984), that the ultimate finding

regardtng inequality of access under amended Section 2 is one of

pure fact, subject to the clearly erroneous standard.T

Cf. Pullman-standard v. Swintt 456 U.S. 273t 287-88 (1982)

(Inference of intentional discrimination from difierential impact

of seniority system under Tit1e VII nis a guestion of pure fact,

subject to RuIe 52(a) ts clearly erroneous standard.n) i Anderson

v. Bessemer,

-

[J.S.

-r

53 U,S.L.[.I. 4314 (1985) (fhe Fourth

Circuit nmisapprehended and misappliedn the cLearly erroneous

standard in reversing a district courtts finding of intentional

discrimination under TitIe VfI).

The guestion which remains, then, is whether the district

courtts independent consideration of the record was clearly

erroneous under Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a). It plainly was not. The

history of.black electoral success in the challenged districts in

North Caro1 ina bears out the conclusion that this f actor lreighs

in favor of a finding of unequal political opportunity. The

statewide figures reveal that there were never more than four

blacks in North Carolina's 120-member House of Representatives

on grounds other than race, emerges f rom the effect of the state

action . . .t).

Tlndeed, the Department of Justice itself has in the past

acknowledged the applicability of the clearly erroneous standard

to a final Section 2 conclusion. See Brief for the United States

at 26 n.10, 5, 739 F.2d 1529

(11th Cir. 1984) ('Discriminatory result is essentially a factual

issue and is therefore subject to review under Rule 52rs clearly

erroneous standard. n) .

10

between 1971 and 1982, and never more than two blacks in the

50-member State Senate from 1975 to 1983. 590 F. Supp. 345 at

3G5. In the period from l-gTO to 1982, black Democrats in general

elections within the chaLlenged districts Iost at three times the

rate of white Democrats. R. 114. These statistics undeniably

demonstrate racial inequalitY.

fhe district courtrs findings with respect to the 1982

elections erere also supported by considerable evidence. Signifi-

cantly, in 1982, not a single white Democrat lost in any of the

general elections in the challenged districts, though 28.5t of

black Democrats lost. R. LL4, 115. The evidence on which the

district court relied amply supported its conclusion that "there

were enough obviously aberrational aspects in the most recent

elections' to reject the contention that blacks were not stil1

disadvantaged by the multi-member districts. 590 F. Supp. at

357. fn House District 36, a black Democrat $ron one of the 8

seats in the district in 1982. Since there were only seven white

candidates for the 8 seats in the primary, it was a mathematical

certainty that a black would win. Id. at 359. In tlouse District

23, there vrere only 2 white candidates for 3 seats in the 1982

primary, and the black candidate who lron ran unopposed in the

general election, but stiIl received only 43S of the white vote.

Ld. at 370. In three other elections prior to 1982, the same

black candidate won in unopposed races, yet failed to receive a

maj or ity of white votes in each contest. f3]. In tlouse District

39, 2 b|acks won election in 1982 due to an atypical set of

11

circumstances unlikely to recur in the near future, including an

unusually Iarge number of white candidates who fragmented the

white vote. R. 87-88. These two candidates h,on despite the fact

that they were ranked seventh and eighth among white voters out

of eight candidates in the general election. 590 F. SupP. at

370. Though a black incumbent won the L982 election in House

District 21, expert testimony at the trial indicated that the

high levels of racial polarization in that district made is .very

problematicn for a black candidate to succeed a retiring black

incumbent. R. 102. rinally, in Senate DistticE 22, no black

Senator rras part of the 4 representative delegationr despite the

fact that the population of that district was 24.3t black. uone

of these elections contradict the district courtrs conclusion

that:

[T]he success that has been achieved by black

candidates to date is, standing alone, too

minimal in total numbers and too recent in

relation to the long history of complete

denial of any elective opportunities to

compel or even arguably to support an

ultimate finding that a black candidaters

race is no longer a significant adverse

factor in the pol itical processes of the

state -- either generally or specifically in

the areas of the challenged districts.

590 F. Supp. at 357.

fvo additional factors support the district courtrs finding

regarding minority electoral success. First, even in elections

where black candidates were victorious, h,itnesses for the

plaintiffs and defendants alike agreed that the victories were

Iargely due to extensive single-shot voting by blacks. R. 85,

L2

181, 182, 184, 1099. Even the defendantsr expert witness

conceded that, nas a general ru1e, n black voters had to

single-shot vote in the multi-member districts at issue in order

to elect black candidates. R. 1437. CIearly there is not equal

opportunity to participate in the political process if blacks are

compelLed to resort to tactics which are not reqrir"a of whites,

and which confine minority influence to one candidate out of a

whore srate of candidates.8 rhe suggestion that electoral

success through single-shot voting precludes a conclusion of

impermisslble vote dilution erroneously focuses on equality of

result instead of equality of opportunity, which is exactly the

error the appellants accuse the district court of committing !vhen

they mistakenly claim that the court required proportional

representation. Sgg infra. at _. Since equality of oppor-

tunity is the object of the Voting Rights Act, that Act is

clearly violated where electoral practices disproportionately

burden the ability of minorities to participate in the political

process' even if minorities have managed to achieve some benef i-

cial results under those onerous procedures.

The district court also acknowledged the evidence at trial

which indicated that, in some of the I982 elections, ',the

pendency of this very litigation worked a one-time advantage for

black candidates in the form of unusual politicar support by

Srhough single-member districts would also confine each

voterr s influence to one candidate, the critical difference isthat there would be true equality of opportunity, since

singre-shot voting would no longer be a technique required onlyof black voters.

13

white leaders concerned to forestall single-member districting.o

590 F. Supp. at 367 n.27. This is exactly the concern which led

the court in zimmer v. McKeithenr 435 F.2d 1297 (5th cir. 1973)t

to reject assertions identical to those advanced by the appel-

lants here. In a passage cited by the Senate Reportr see

S. Rep. at 29 n.1I5, the Zimmer court noted Ehat minority success

at the ballots can be attributed to a number of political reasons

consistent with the existence of racial vote dilution, including

attempts by the majority to nthwart successful challenges to

electoral schemes on dilution grounds." 485 F.2d aE 1307.

Congress obviously did not contemplate that nsuccessn of this

kind would in fact forestall the award of a remedy for minority

vote dilution.

Appellants' preoccupation with the district courtrs finding

on one factor out of many considered in the court's evaLuation of

the aggreghte of circumstances suggests a misconception of the

meaning of Section 2 of the voting Rights Act Amen&nents. The

Senate Report explicitly warns against undue emphasis on one

circumstance to the exclusion of the totality of circumstances.

S. Rep. at 29 n.118 (nThe failure of plaintiff to establish any

particular factor, is not rebuttal evidence of nondilution.

Rather, the provision requires the courtrs overall judEnent,

based on the totality of circumstances and guided by those

relevant factors in the particular case, of whether the voting

strength of minority voters is . . . trlinimized or canceled

out. I n). Section 2 itself contemplates only that minority

l4

electoral success "mayn be considered aS one relevant circum-

stance. 42 U.S.C. S 1973. Appellantsr endeavor to treat it as

the ascendant factor under Section 2 is manifestly at odds with

the language of the Voting Rights Act.9 Congress unmistakably

intended that other facets of electoral politics and procedures

as well as the local history of racial discrimination and

segregation would play equally important roles in courtsr

ultimate determinations under Section 2. The district court's

extensive analysis of those other factors is completely ignored

by the appellants. fheir attempt to persuade this Court to

consider recent North Carolina elections in a historical vacuum

is precisely what Congress intended to prevent in adopting a

results test for vote dilution claims. It is also precisely what

appellants accuse the district court of doing when they contend

that it employed a proportional representation standard. A fair

gRppellants' claims are also contrary Eo the weight of

opinion- in federal cases handed down subsequent t9 the 1982

amendrnents. Egg, e.q., Ketchum v. Bvrner 740 F.2d 1398 (7th

Cir.1984) cert. deniedr 53 U.S.L.W. 3852 (U.S. June 3t 1985)

(Section 2 violation found in Chicago's aldermanic ward p}?!

despite the fact that nin Chicago numerous black public offi-

ciais, including aldermen, state senators and representatives,

U.S. representatives and nOw the Mayor have been elected.n

Id. at 1405); Sierra v. EI Paso IndeB- School.Dist', 591

F. Supp. 802 (W.D. fex. 1984) (At-1arge election of school board

trustiis invalidated under Section 2 despite the fact that the

43t Mexican-American voting population had succeeded in electing

25* Mexican-American trustees since 1950, a difference termed by

the court nnot great enough to be significant in and of itself."

Ld., at 810); Po] itical Civil Voters Oro. v. Terrell, 555

F. Supp. 338 (N.D. Tex, 1983) (At-large election of city.council-

men iirlal idated under Section 2 despite the f act that, with a

33.5t black voting population, nsince the late I950's, black

representatives hive constituted approximately 20t of the city

council and 14t of the school board. n Ig. at 348) .

15

reading of the opinion below reveals that the district court

carefully and meticulously appraised the political and historical

context of recent electoral successes. It is the appellants who

nori, urge that political and historical context be disregarded.

fhis interpretation of Section 2 is undisputably erroneous and

should emphatlcally be rejected by this Court.

B. The District Court ProPerlY

Evaluated the Uncontradicted

Evidence of Racial Bloc Voting

to Determine the Extent to which

Voting was RaciaIly Polarized.

Based on evidence presented by expert witnesses and cor-

roborated by the direct testimony of lay witnessesr the district

court concluded that nwithin all the challenged districts

racially polarized voting exists in a persistent and severe .

degree. " 590 F. Supp. at 367. This determination tras f uIly

supported by the uncontroverted facts presented at trial. The

court below properly weighed the extent of racial pola rLzation as

one factor in the totality of circumstances indicating lack of

equal opportunity for minorities to participate in the political

process and elect representatives of their choice.

The district court relied in part on testimony by plain-

tiffst expert witness, DE. Bernard Grofman, whose comprehensive

study of racial voting patterns in 53 elections in the challenged

districts revealed consistently high correlations between the

number of voters of a specific race and the number of votes for

candidates of that race. These correlations rrrere so high in each

of the elections studied that the probability of occurrence by

15

chance was less than one in 1001000. 590 F. Supp. at 358. Ng

black candidate received a majority of white votes cast in any of

the 53 electionsr including those which were essentially uncon-

tested. rd. whttes consistently ranked black candidates at the

bottom of the field of candidates, even where those candidates

ranked at the top of bl.ack voterst preferences. Id. The

district court individually analyzed elections in each of the

challenged districts to conclude that, in each district, racial

polarLzation "operates to minimize the voting strength of black

voters. n Id. aE 372. fhis conclusion was buttressed by the

observations of numerous lay witnesses involved in North Caro1 ina

electoral pol itics. E€9, grS-r R. 431. Given the overwhelming

and unconLradicted facts of this case, there is no question but

that racial polarization in eech district was, as the district

court properly found, nsubstantial or seveE€. n 590 F. Supp. at

372.

Despite the unrebutted evidence of racial bloc voting,

appellants contend that the courtrs finding was incorrect as a

matter of 1aw. Specifically, appellants accuse the court of

adopting as a measure of racial bloc voting the standard of less

than 50t of white voters casting a baIlot for the black candi-

date. Appellantsr Brief at 36. This assertion lacks any support

in the opinion below. The court indicated that the purpose of

both methods of statistical evaluation relied upon by the

plaintiffs' expert witness $ras simply nto determine the extent to

which blacks and whites vote differently from each other in

t7

relation to the race of candidates.' 590 F. Supp. at 367 n.29.

These methods of analysis, approved by the court as accurate and

reliab1e, plainly have nothing to do with a 50t threshhold testr

as appellants cIaim. In fact, it was only after concluding that

substantively significant racial polacization existed in all but

two of the elections analyzed that the district court noted that

no black candidate had received a majority of the white votes

cast. The court specifically referred to this finding as one of

a number of n taldditional f actso which ngJ.Plgll the ultimate

finding that severe (substantively signiflcant) racial polatLza-

tion existed in the multi-member district elections considered as

a whole.n Ld. at 358 (emphasis supplied). Thus, it is obvious

that this observation, which appellants slngle out from a whole

paragraph of nadditional f acts, n !'ras not meant to state a

standard for racial polarization, but rather to indicate further

support for a conclusion already reached under a different

standa rd. I 0

In its brief as amicus curiae, the United States also

misconstrues the standard under which the district court analyzed

the evidence. fhe principal method for measurement of racial

polarization relied on by the court below $ras statistically

significant correlation between the number of voters of a

10th" Department of Justice has also conceded in its juris-

dictional brief that 'IaJppellants' restatement of the district

courtrs standard for racial bloc voting is impreciser" since "the

district court did not state that polacLzation exists unless

white voters support black candidates in numbers at or exceeding

50t.n Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae at 13 n.10.

18

specific race and the number of votes for candidates of that

race. g.E 590 F. Supp. at 367 | 358. Since the governmentr s

criticism focuses on the lower court's definition of substantive

significance grithout acknowledging the court's initial definition

of racial polacization as also requiring statistiqa'l signif i-

cance, its conclusion that a ominor degree of racial bloc voting

would be sufficient to make out a violation" is misleading.

Br. for U.S. at 29. A Iow correlation would on the contrary

properly result in a finding of a low extent of polarization,

which weighs against an ultimate conclusion of impermissible vote

dilution.1l

fhe government advocates an alternative standard for gauging

11rho", 'th" government's absurd hypothetical situation in

which a white candidate receives 51t of the white vote and 49t of

the black vote and an opposing black candidate gets the reverse

would clearly not constitute severe polarizationr ds the govern-

ment contends. See Br. for U.S. aE 29. In fact, since such a

disparity i.rould not be statistically significant, it would not

constitute racial polarization at all. The suggestion that the

district courtrs definition of racial polarization would invali-

date numerous electoraL schemes across the country, see i.d. at

30, conveniently ignores the fact that the courtrs correlation

analysis correctly focused on nthe extent to which voting

. . . is racially polarized.n S. Rep. at 29 (emphasis

supplied). Racial polarization is properly evaluated as a

question of degree, and not as a dichotomous characteristic which

is 1egalIy conclusive if substantively significant and irrelevant

in aII other cases. Furthermore, it is incorrect to suggest that

the existence of racial polarization alone is sufficient to

strike down any electoral district in the country. Congress

considered and rejected numerous similar contentions in its

debates on the proposed amendrnents in 1982 r f,€peatedly reaf-

firming that proof of a few of the Zimmer factors alone would not

satisfy the requirement that courts consider the totality of

circumstances. E, grS..r S. Rep. at 33r 34. Thus, the district

courtr s analysis does not, as the government asserts threaten the

Iegality of innumerable election districts throughout the

country.

19

the existence of substantively significant racial polarization

which would require only that nrminority candidates [do] not lose

elections solely because of their race.'n Br. for U.S' at 31

(quotlng Roqers v. Lodge, 458 U. S. 613 (1982) ). This standardr

they argue, would render racial bloc voting nlargely irrelevantrn

i-d., if a Losing black candidate receives some unspecif ied amount

of white support, since such support would demonstrate that

factors other than race play a role in the election. fhis

suggestion fails to appreciate the import of Congress' rejection

of the intent standard in racial vote dllution cases. There are

always factors other than race in an election, and it will never

be possible to prove that a black candidate lost osolely because

ofn race. Under a results test, lt is simply irrelevant whether

whites vote differently from blacks because of racer or because

of some other factor which may be closely associated with race.

fhe enactmbnt of amended Section 2 made the motivations of

legislators and voters irrelevant to such claims. Regardless of

the actual basis for the creation of multi-member districts, or

the reasons for the existence of racial bloc voting, Congress has

made it plain that such circumstances in combination can result

in a dilution of the minority vote, and that such a result is no

more tolerable under the Voting Rights Act than is intentional

discrimination. Thus, the district court properly declined to

focus on the question of whether blacks lost elections solely

because of racer dnd instead concentrated on the practical result

of white voters' unwillingness to vote for black candidates,

20

which was consistently to defeat the preferences of black voters

as expressed at the poL1s.

This point is also responsive to appellants' objections to

the statistical methodology relied upon by the district courE'12

It simply does not matter whether rrace is the only explanation

for the correspondence betweeen variabl€srn Appellantsr Brief at

42, or whether other factors account for differential voting

patterns. The fact is that where such differential voting along

racial lines exists, for whatever reasonsr the preferenceS of

black voters can consistently be defeated by the majority in the

context of at-Iarge or multi-member district elections. Race

itself does not have to be the motivating factor; the question is

what result racial polacization has on the opportunity for blacks

to elect representatives of their choice.

This court has already rejected the arguments of those who

would reintroduce an intent rqluirement into Section 2 Iitigation

by requiring that race be the sole motivation for racial polari-

zation. In MississioBi Republ ican Executive Committee v. Brooksr

U. S. , 83 L. Ed. 2d 343 (1984) , precisely the same

objections to a district court's analysis of racial bloc voting

$rere made as those advanced here:

The use of a regression analysis which

correlates only racial make-up of the

precinct with race of the candidate nignores

l2Significantly, appellants' o$rn expert witness agreed that

correlati5n analysiE wai-a standard methodology for measuring

voting polarization, R. 1445, and that all of the elections

analyiea by the appellees' expert witness demonstrated statisti-

ca1ly significant correlations. R. 1446.

2L

the real ity that race . . . may mask a host

of other explanatory variables. n IJones

v. City of r,ubbock, 730 F.2d 233, 235 (5th

Cir. fgAa) (Higginbotham concurring). l

Cf. Terrazas v. CIements, 581 F. Supp. L3291

f :St-S (ll. p. Tex. L984) (detailed discussion

of proof regarding polarized voting).

Jurisdictional Statement at 12-13. This Court summarlly affirmed

the district courtt s decision in that case. Since Summary

affirmances nreject the specific challenges presented in the

statement of jurisdicEion, n ttlandel v. gradley, 432 U. S. L73t 176

(Lg/7), the use of bivariate regression analysis has been

sanctioned by this Court as a measure of racial polarization.13

Appellantst proposed racial bloc voting standard is also

inconsistent with Congresst understanding of that concept when it

passed the 1982 amendments. In delineating the factors relevant

to a showing of unequal opportunity to participate in the

political process, Congress relied heavily on federal circuit

courtinterpretationsof@,412U.s.755(1973).

tiftcne of those appellate court cases which addressed the issue of

racial polarlzation adopted a definition which supports the

13thi" Court has also on several occasions affirmed a lower

courtr s rel ian"" on methods other than multivariate analysis t-o

measure bloc voting. SCSr 9.,S.l.r City of Port= 4Elfrur Yt= tlni!q!

ia;aea, St7 F. srp6. 987,1007 n.135- (D.D.C. 1981), affrd, 459

fr:frI59 (1982) (ir6mogeneous precinct analysis); _r'9dqq Y., Buxtonr

civir No. 176-55 ( s. D.- Ga. 19i8) , af f 'd, 639 F.2d 1358 (5th

gir. 1981) , af f 'd'sub nom. Rogers v. todget 45_8 _9. 9. 513 (1982)

t"oi"iitilli ,472-

i.Supp.22l|izZ,n.i6,44qU.s.}56(1980)

iipp.o,iing use-ot'.t"tisticaI correlation analysis.as'the surest

method of demonstrating racial bloc voting, n byt, il absence of

sufficient data base, ielying on nonstatistical evidence); Graves

v.-euin"", 343 F. Supp. l-Oq, 731 (W. D.

-

Tex. 1972) , af f I d sub

, 4L2 U. S. 755 (1973) (nonstatistical

proof).

22

standard urged here. In fact, most of them required no formal

proof of polarization whatsoever.l4 See e. s. r @iJu)

Parish policy .lurv, 528 F.2d 592 (5th cir. l-g75)i Robinson

v. Commissioners Court, 505 F.2d 674 (5th Cir. t974) i Moore

v. Leflore County Board of Election Commissionersr- 502 E.2d 621

(5th Cir. 1974) i Turner v. McKeithent 490 F.2d 19L (5th

Cir. 1973). Every affirmed district court decision which did

rely on formal proof did so on the basis of evidence and statis-

tical analysis comparable to that presented to the district court

below. Sgg, e.o., Bolden v. Citv of Mobile, 423 F. Supp. 384,

388-89 (s.D.AIa. 1976) (regression analysis)r affrdt 571 F.2d 338

(5th Cir. L978), revrd on other qrounds, 446 U.S. 55 (1980);

Parnell v. Rapides Parish Schoo1 Board, 425 F. Supp. 399, 405

(w.D. La. L976) (Pearson correlation analysis and retrogression

analysis), afffdr 563 F.2d 180 (5th Cir. 19771, qS-LE. deniedr 43S

U. S. 915 (1978) ; Kirksev v. Board of Supervisors of [Iinds Countv'

402 F. Supp. 658' 672-7 3 n.4 (S.D. Miss. 1975) (correlation

analysis), af f rd, 554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir. 1977) , ge-Lt. denied, 434

U.S. 958 (1977)i see also Nevett v. Sidest 571 F.2d 209, 223 n.18

(5th Cir. 1978) (approving nonstatistical means of proving racial

polacization and citing nolden district courtrs use of statisti-

caI analysis). fn none of these cases did the federal appellate

court object to the district court's failure to inquire whether

black candidates lost elections nsolely because of their race.n

14th" original z immer

include racially polarized

F.2d 1297, 1305 (5th Cir.

themselves did not evenf acto rs

voting.

1973).

23

See Z immer v. McKeithen, 485

In sum, Congress surely did not contemplate such a definition

when it resolved to eliminate the intent requirement and return

to the legal standards prevalent among the circuit courts prior

to ug!.i.Le. The district court below analyzed the extent of

racially polarized voting in the manner which best comports with

congressionar intent, and properly considered bloc voting as one

of the factors bearing on equal ity of opportunity to participate

in the pol itical Process.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT RQUIRE GUARANTEED

ELECTION OF BLACK TEGISLATORS IN NUMBERS PUAt

TO TEE PROPORTION OF BLACKS IN NORTH CAROLINAI S

POPULATTON.

Appellants charge that the district court below imposed a

standard for vote dilution under Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act which is expressly prohibited by the language of Section 2

itself, specifically that of guaranteed election of members of a

protected plass 'in numbers equal to their proporLion in the

population.nl5 42 U.S.C. S 1973. There is no evidence in the

district courtr s opinion to support this contention. It cannot

seriously be disputed that the court below properly evaluated the

evidence to conclude that, given the totality of relevant

circumstances, black voters in the challenged districts had less

opportunity than did other members of the electorate to partici-

lseppetlants make this argument despite the fact that the

district- iourt expressly repudiated the concept of guaranteed

proportional representation. The court below cited the dis-

Llaimer in amended Section 2 Lo conclude that nthe fact that

blacks have not been elected under a challenged districting plan

in numbers proportional to their percentage of the population

. . . does not alone establ ish that vote dilution has resulted

from the districting plan." 590 F. Supp. at 355.

24

pate in the political process and to elect representatives of

their choice. Appellantst insistence that a court which faith-

fully appl ied the judicial analysis mandated by Section 2 was in

fact imposing a requirement of proportional representation can

only be characterized as an attempt to resurrect q debate which

has unquestionably been considered and resolved by CongreSs.

fn City of Mobile v. Boldent 446 U.S. 55 (1980), a plurality

of this Court held that a successful claim of racially discrimi-

natory vote dilution required a showing of intentional discrimi-

nation, whether brought under the fifteenth Amendnent, the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendmentr or the former

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The plurality opinion

provoked a vigorous dissent by Justice Marshallr who argued that

vote dilution cases r,rere rooted in the "f undamental rights "

strand of equal protection jurisprudence, under which a discrimi-

natory impact is constitutionally objectionable regardless of

discriminatory intent. Marshall expressed the view that " Iu]n-

constitutional vote dilution occurs . . . when a discrete

political minority, whose voting strength is diminished by a

districting scheme proves that historical and social factors

render it largely incapable of effectively utilizing alternative

avenues of influencing public policy." 446 U.S. at 87 n.7

(MarshaIl dissenting) .

The Mobile plurality responded that Marshallrs impact test

amounted to a declaration that minority groups have a "federal

constitutional right to elect candidates in proportion to their

25

numbef,s.'t Ld. at 63 (citation omitted). fhe pluraI ity contended

that "gauzy sociological considerationsn could not 'exclude the

claims of any discrete political group that happens, for whatever

reason, to elect fewer of its candidates than arithmetic indi-

cates it might. n Ld. at 53 n.22. Such a result, -the Court

concluded, simply vras not required by the Egual Protection CIause

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Ld. at 55 n.4.

It is in this context that Congress enacted the amended

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act in 1982. In amending Section

2, Congress unequivocably resolved the proportional representa-

tion dispute between the pIurality and dissent in lllgbj-Ls. The

debate on the amen&nents repeatedly addressed the issue raised by

this Court in Mobile of whether an impact test could be

distinguishable from a proportional representation requirement.

Opponents of the changes echoed the plurality view in Ug-biIS,

claiming that there coul d be no intel l igible distinction. Sg9,

e.o., 1 Senate Hearinqs 3 (1982) (oPening Statement of Senator

Orrin tlatch) ('In short, what the rresults' test would do is to

establish the concept of 'proportional representationr by race as

the standard by which courts evaluate electoral and voting

decisions.n) Ho$rever, the Senate Report emphatically dismissed

this notion. See, grS-r S. Rep. at 33. As previously notedr the

Senate Report enumerated seven factors to govern a courtts

resolution of the ultimate issue: whether minority voters have

an equal opportunity to participate in the political processes

and to elect candidates of their choice. S. Rep. at 28. In

25

evaluating those factors and reaching a conclusion on the

question of equal opportunity, the court must comply with the

disclaimer in section 2, which reads as follows:

Theextenttowhichmembersofaprotected

class have been elected to office in the

State or political subdivision is one

tcircumstancet which may be consideredr'

provided that nothing in this section

establ ishes a right to have members of a

protected class elected in numbers equal to

their proportion in the population.

Thus, the proponents of the amen&nent to Section 2 tere

plainly unconvinced by the Mobile plurality's skepticism con-

cerning the posslbility of distinguishing a EiEg-Zimmer results

test from a proportional representation requirement. The Senate

Report makes it clear that the focus of inquiry is not on one of

the enumerated factors in isolation; rather, the factors are to

be evaluated in combination to determine whether they operate '

together to deny egual opportunity to participate in the politi-

cal process. For this reason, the contention that lack of

proportional representation alone, or even in combination with

one other factor, wiIl constitute a violation was expl icitly

rejected. S. Rep. at 34.

Given this background, appellants' claim that Ehe court

below employed a proportional representation standard is properly

viewed as an attempt to revive a view held by a plurality of this

Court, but subsequently repudiated by Congress acting within its

constitutional povrers. The district court duly examined each of

the zimmer factors specified in the Senate Report, and properly

concluded that the totality of those factors evidenced an

27

impermissible dilution of minority voting strength. appellantsr

effort to portray the lower courtrs standard Zimmer analysis as

an imPosition of proportional representation is best described as

evasion of an uneguivocable congressional pronouncement that the

Section 2 results test is not eguivalent to proportional repre-

senta tion.

As evidence of the proposition that the district court

erroneously applied a standard of guaranteed proportional

representatlon, appellants focus on one paragraph from the

courtrs opinion, which reads as follows:

The essence of racial vote dilution in the

@ sense is this: that

primarily because of the interaction of

substantial and persistent racial polarizaton

in voting patterns (racial bloc voting) with

a challenged electoral mechanism, a racial

minority with distinctive group interests

that are capable of aid or amelioration by

government is effectively denied the pol iti-

cal polrer to further those interests that

irubmers alone would presumptivelyr see q,Ililsil

Jewish organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144,

166 n.24 (1977) t give it in a voting constit-

uency not racially polarized in its voting

behavior. See Nevett v. Sides, 57 I F.2d 2091

223 & n.l5 (5th Cir. 1978).

590 F. Supp. at 355. Through misleading manipulation of this

single paragraph, appellants conclude that the decision below was

based exclusively on the failure of blacks 'to consistently

attain the number of seats that numbers alone would Dresumptivelv

qive them, (i.e. in proportion to their presence in the popula-

tion). " Appellants' Brief al 20 (emphasis in original). By

misinterpreting one phrase of the courtr s opinion without

reference to the citations which elucidate its meaning, and by

28

isregarding the ful1 text of the sentence and paragraph in which

hat phrase appears, appellants have misrepresented the legal

tandard applied by the court below'

When the paragraph at issue is read as a whole, rather than

solating six words out of context, it becomes plain that the

ristrict court !,ras addressing the issue of racially polar ized

oting, and not articulating a requirement of proportional

epresentation. Significantly, in their mischaracterization of

;he opinion below, appellants disregard most of the sentence on

,hich they so heavily rely. In fact, the district court referred

:o npol itical power . . . that numbers alone would Presumptively

tive [a racial minority] in a votinq constituencv not racial ly

plarized in its voting behavior. n 590 F. Supp. at 355.(citation

rmitted) (emphasis supplied). If this sentence was meant, to

itate a proportional representation standard, there is no

rxplanation for the.court's reference to racial polarization.

)ontrary to appellants' aSsertions, the Court also makes no

:eference at all to "the number of seats" to which minorities are

lntitled. Political power absent racially polarized voting

;imply has nothing to do with proportional representation, a

;tandard which would mandate that racial minorities be elected in

lroportion to their percentage of the population. If black and

vhite voters aI ike express exactly the same po1 itical prefer-

)nces, each race will necessarily be represented by the candi-

lates of their choice. These candidates may or may not be

?roportionally representative of the voting poputation; the point

29

ose rlts ttBuLL fo| 00nEsftc sxtPtEtfs ilto foi s,ttPilEtrs fnot PUEBfo nrco to rt E a.s.a

filL out PUBP,J AfiE^S. fon tssrsilxcf, cl Ll 8ln-2?8-5:r55 foLL faEE.

seE Stcx 0f t0ilt sEf fon conPlEle PFEPAn ft0ll nsfaucf,0ts.

ISENDER',S FEDERALEXPRESS ACCOUNTNUMBER I q

51868 C:On-,:)615-

.From ffour Name) Yo!r Phone Number (Very tmponant)

(ana ) itr

-t.tt

To lRsioient s Namel

i}t --a irlrlrr tha

Rerpgts Phom NUlfu Nery lmpor€nl)

( ,t r) tt a-t ot.t

CompZil- Department/Floor No

LA;Y[1S C.1TIU [:{IF TVIL TI6HTS

company Departnsl/Fl@r No

Strel Addres

l+O0 EYi ST'lh STi r.''t0

Exact Stret Addres luiol L0. ,otB u P.o.o 2:t, C&t l,iil l}/tt lhlifrt d ML l, Exfr. C,,t .)

City Slate

dAJH TNCTCT

City State

AnEtLt r?0L?791?a

ZrP @Zip Code Bequtred For Corst lnvorc ng

2 i', :') 3 'r

ZrP Stret Addr6 Zr p Rquted tb f,o. u @ 4 c*l

toott

rfottB BTLLNE BEFESEttCE nF0nnAf'Oll (FlBSr 24 CflAnACfEnS Y'LL APPEAn 0fl fivoloE.l

D

,t010 foe Ptcx-uP tf f,tts lE0E

Skel Addrs (Se Seryrce Gu'd, or Call 800-238-:1355)

,l

PAf ltEilIflu si'oo''

! c""n

-

Bll R(,mnr s ftEr Accr No

-LJ r tt ,n trne mtow u

FdEr Accl No or Malor Credn Card No

&ll 3ro Party FedE Bll Crdn CardNO tr

L. SEBU'CES

, c,tEct( otlr oilE Box

OEL'IENf A'ID SPECIAL

'TAIIOL'N8cflEc,( sEnvrcEs nEQwnEn

r6tr6fl I,Jclt o0r oe.cutto

JILUE

ZIP eZrp Code ol Strel Address Required

a PBlOBlff ,

-UJtrifrtaiil,t h6 o,.,"'sir o" *., 6 L) LEfTEfr

Us.g You, Pac@,.g (tur Pacbg'n9 9 rr2

0tEnttailf 0ELtlE8f

usno oun PAcxa6fi8

, J I Coune,.Pah Overn'ght Envelope_-12^t:,,

3!?J;qi]',:e,'3 An

4Egx?eiLT:T 8E

SfAII'ABO AIfr

< T-'l h'vPru not lars rhan

" U oono'o"s,nes oau

seBt,cE cott,/,tfttEilf

PROFTry r bvry s *du6 6ny rentuln* Mn'.g

h ruy bke tuo o. mqe turns @F I tu

(HM!d

'3

@@tur rycry sere a.*

STANDAAO ArR b vB ,s g€neraly .err hr.6s &y d nor

r.rerrM. Fond bus.essday hmsy6kethreq mo,eben6s

&ys I mGhnat6 'soubdeolr

g'naryseceaes

1 l'1 E0L0 IOA PrCl-UPGrve he Fdera Erprs

Ll *ors *re,e yo, *anl Fc\age held ,n

sdirtnryr

2 g oELnEn uEExDtr

32 oEt,wn sAfuBDAf ,enacevws

Emp. No. I Date

D Cash Recqved

E h,nsh,ryr

Strret Addres

re

"**y

re@

, f-1 rEsraErE0 tmELES sEBJtcE ,v.,a"a

- U ssu,o l, pacuF tr , E.!a crilF ry6

5 - c,,tsilu suite,tutcE SENIEE lcss)

-

lEnra charge apptr6 r

a]onlw

-

Lbs

tloneasrrctalsEnueE

-

8n

!,

{

"tl

-!.l

':

) .$

: ,l

E

ii

E

i;*

*E

;ii

rr

E

gs

iir

E

B

H

a

a;

ig

=

E

E

;

gg

E

E

E

;

;E

A

3E

gE

B

E

,E

F

E

E

i

E

3e

E

-

3i

J

I

af

fg

gi

g

E

g

*E

,i

ua

E

gi

ffE

gi

in

E

E

,g

B

gE

E

$i

S

lii

gs

ig

st

*

g

i i

ff;

ga

B

T

*l

S

iE

s

F

gi

CfJ""W FOA Cl VI

A~tNGTON

- -~

AIRBILL No.?AL 77D'I7c ,

YOUR BILLING REFERENCE INFORMATION (FIRST 24 CHARACTERS WILL APPEAR ON INVOICE.)

cct No. 0 ~~~ ~~;c:~~~Ex Accl No. 0 ~~~ ~r~~ ~~dw City State

FedEx Acct No. or Major Credit CBrd No.

SERVICES

CHECK ONLY ONE BOX

~ PRIORITY I OVERNIGHT

1 00 o.emlght o.'"""' 6 0 LETTER

Using Yovr Packaging (Our PacKag!og} 9" 1t 1Z'

OrERNIGHT OELirERY

USING OUR I'ACKAGINS

2 0 ~~ri~:~ Overnight Env8ope

3 0 ~~~~~~~~x3.. A 0

4 0 ~~if}~~!~t:,. B D

STANDARD AIR

5 D =;u~i~~ ~:yn

SERVICE COMMITMENT

PRIORITY 1 - DehYery IS 8CheOoled eerty neKt buainess rrtOmlng

1n most.~bons.lt may take two or more buslne6S da'fl, il the

dettinaliOn 11 outakle our primary &ervlc& ar&M

STANDARD AlA - Del1vety IS generally next buSiness day or no1

laterlhltn &ecortd htlsmesaday ttma.ytakelh!eeor more busii'MIM

.,. •- da~llhd-.li~'!ovtlide~primatylel"'ollcew_,s . ~ ....

DELIVERY AND SPECIAL HANDLING

CHECK SERVICES RE(}UIRED

NCKA6ES WEI6HT

YOUR DECLARED DrER ZIP " Zip Code of Street Address Required

rAtuE SIZE

2 ~ OELirER WEEKDAY 0 Retum Sh<pment

r-----r-----t--------r--i-~D~rh~~~·~·~~~ __ _jO~c~~~·~rn~~~·----J;~~~~~

3 0 OELirER SATURDAY I!"" ct<atge aP<'ieol Street Address :-------''-----

4 0 =~I!T=f!~~~=!J~t••

5 0 COIISTAIIT SURYEILLAIICE SERriCE (CSS}

(Extra charge apphes.) City State Zip

6 0 DRY ICE --- Lbs

7 0 OTHER SPECIAL SERVICE - --

sO ~~~~~~~~

!::-.:-::-=....,I("T.,.,....,..--=-...,-:.·""':" ....... ~ .... "'!' ...... ._....:.,I•~T® •• •

ecetved FedEx Employee Number FEC· S·?Sl\t'

Received By:

.1----j__ --

( Rt:V/SION OAT

~~~~TED !.I s=-

===:;;;-;:::::;;;::..._