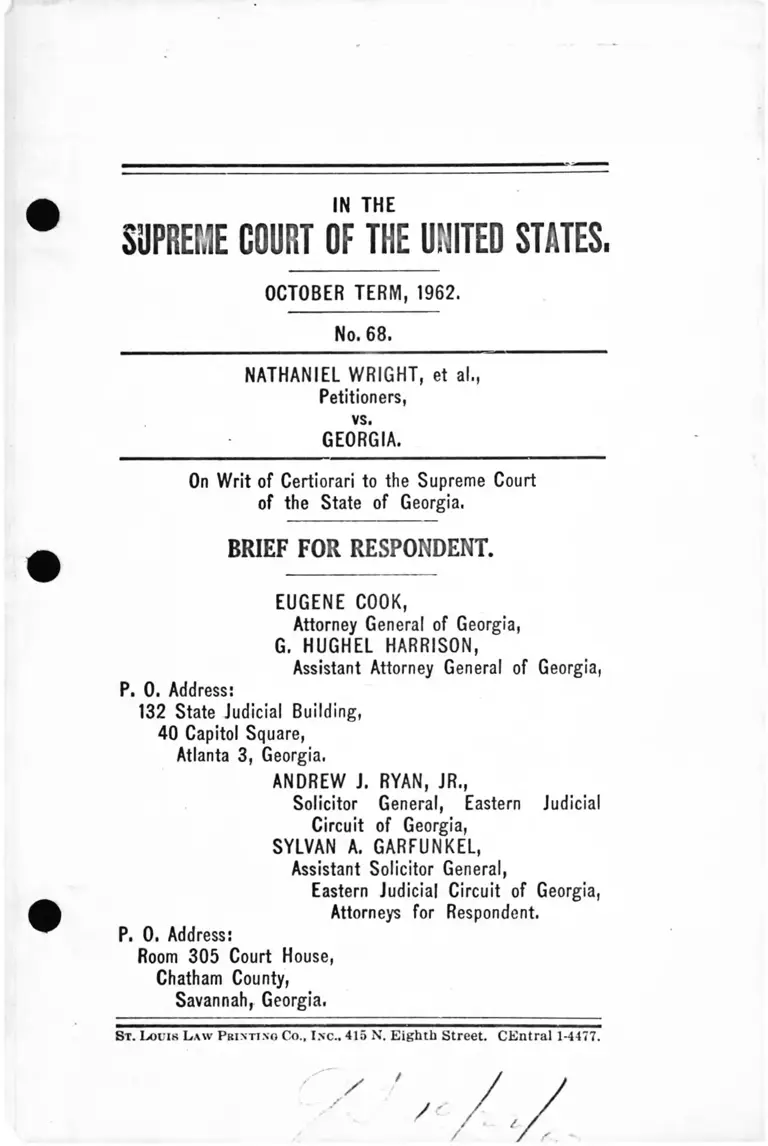

Wright v. Georgia Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. Georgia Brief for Respondents, 1962. 868ae68a-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6f357d3a-81eb-429e-a4fb-8bbe7eaac8d8/wright-v-georgia-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES,

OCTOBER TERM, 1962.

No. 68.

NATHANIEL WRIGHT, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs,

GEORGIA.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Georgia.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT.

EUGENE COOK,

Attorney General of Georgia,

G. HUGHEL HARRISON,

Assistant Attorney General of Georgia,

P. 0. Address:

132 State Judicial Building,

40 Capitol Square,

Atlanta 3, Georgia.

ANDREW J. RYAN, JR.,

Solicitor General, Eastern Judicial

Circuit of Georgia,

SYLVAN A. GARFUNKEL,

Assistant Solicitor General,

Eastern Judicial Circuit of Georgia,

Attorneys for Respondent.

P. 0. Address:

Room 305 Court House,

Chatham County,

Savannah, Georgia,

S t . L o u is L aw P r in tin g Co., I n c .. 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Pago

Questions presented ........................................................ 1

Statement ......................................................................... 2

Argument I ................................................................... 7

Petitioners argue that the statute under which they

were convicted was too vague and indefinite to

provide an ascertainable standard of guilt........... 7

Argument IT ..................................................................... 14

Petitioners further argue that the judgment below

does not rest upon adequate non-federal grounds

for decision............................................................... 14

Conclusion ........................................................................ 18

Cases Cited.

Chaplinskv v. New Hampshire, 315 IT. S. 568, 86 L. ed.

1031 ............................................................................... 9

Edelman v. California, 344 U. S. 357. . . . 1..................... 17

Fox v. The State of Washington, 236 U. S. 273, 59 L.

ed. 573 (1914) .............................................................. 9

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157, 7 L. Ed. (2) 207.. .8, 11

Glasser v. United States, 315 IT. S. 60, 70..................... 15

Henderson v. Lott, 163 Ga. 326 (136 S. E. 403) ......... 15

Herdon v. Georgia, 295 IT. S. 441..................................... 17

Lawrence et al. v. State Tax Commission of Missis

sippi, 286 IT. S. 276...................................................... 17

Michel v. Louisiana, 350 U. S. 91........................ 17

11

National Labor Relations Board v. Fanstoel Metal

Corporation, 306 U. S. 240, 83 L. ed. 027................... 11

Parker v. Illinois, 333 U. S. 571.................................... 17

People v. Galpern, 259 N. Y. 279, 181 N. E. 572........... 9,13

Samuels v. State, 103 Ga. Appeals 60, 118 S. E. 2nd

231 (1901) ..................................................................... 7

Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U. S. 313...................15,10,17

Terre Haute I. R. Co. v. Indiana, 194 U. S. 579, 589. .10, 17

Union P. R. Co. v. Publie Serviee Commission, 248

U. S. 07........................................................................... 10

IN TH E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1962.

No. 68.

NATHANIEL WRIGHT, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

GEORGIA.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Georgia.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.

i

I.

Whether the conviction of petitioners for unlawful as

sembly denied them due process of law under the Four

teenth Amendment, when they were convicted on evidence

which showed that they were grown Negro men who took

over a playground in a predominantly white neighbor

hood at a time when the playground was reserved for

and was to be used by school children and they refused

to leave when requested by the police.

IT.

Whether the decision below asserts any adequate non-

federal grounds for limiting consideration of an aspect

of an important constitutional right where the court

below determined that such right had been abandoned.

STATEMENT.

Petitioners were convicted of violating Section 26-5301,

Georgia Code Annotated in that they did assemble in the

County of Chatham on January 23, 1961 at Daffin Park

for the purpose of disturbing the public peace and refus

ing to disburse (sic) on being commanded to do so by

Sheriff, Constable ai.d Peace Officer, to wit: W. H. Thomp

son and G. W. Hillis . . . (R. 8).

The State of Georgia introduced four witnesses, the first

witness, Officer G. H. Thompson stated:

When we arrived at this Basket Ball Court we

found around seven colored hoys playing basket hall

there . . . (R. 39).

They were pretty well dressed at that time; some

of them had on dress shirts, some of them had on

coats—not a dress coat, hut a jacket. I didn’t notice

what particular type shoes they had on, as far as I

know they didn’t have “ Tennis shoes” on. I am

familiar with the type of shoes that people wear

when they play basket hall, they didn’t have that

type of shoes on as well as I remember . . . (R. 39).

I think that these defendants ranged in age from

23 to 32 . . . (R. 39).

There is a school nearby this Basket Ball Court, it

is located at Washington Avenue and Bee Road, T

mean, at Washington Avenue and Waters. There is

another school on 44th Street—there are two schools

nearby; T believe that they are both “ grammar”

schools. T patrol that area and the children from

these schools play there, they come there every day

T believe, I believe they come there every afternoon

when they get out of school, and T believe they come

there during recess. The school, I believe, gets out

about 2:30 in the afternoon, and this was around 2:00

o ’clock . . . (R. 40).

— 3

When I came up to those defendants I asked them

to leave; I spoke to all of them as a group when I

drove up there, and I asked them to leave twice, but

they did not leave at that time. I gave them an op

portunity to leave. One of them, I don’t know which

one it was, came up and asked me who gave me orders

to come out there and by what authority I came

out there, and I told him that I didn’t need any

orders to come out there. The children from the

schools, would have been out there shortly after that.

The purpose of asking them to leave was to keep

down trouble, which looked like to me might start—

there were five or six cars driving around the park

at the time, white people. They left only after they

were put under arrest, they were put under arrest ap

proximately 5 to 10 minutes after I told them to

leave. It seemed like to me that they were welcom

ing the arrests, because all of them piled into tin*

car, Officer Hillis’s car, at the time, and he had to

stop them . . . (R. 4fi).

On cross-examination Officer Thompson further testi

fied:

Under ordinary circumstances I would not arrest

hoys for playing basketball in a public park. I have

never made previous arrests in Baffin Park because

people played basketball there . . . (R. 41).

On redirect he stated:

There have been colored children in Daffin Park,

hut I did not arrest those children, but I arrested

these people because we were afraid of what was

going to happen. Colored children have played in

Baffin Park, and they have fished there . . . (R. 4*2).

The next witness the State put up was Carl Hager,

Superintendent of the Recreational Department of the

City of Savannah. He stated:

— 4 —

As Superintendent I am over all of the playgrounds

in the City of Savannah, Chatham County, Georgia;

that includes Daffin Park and all the other parks that

have playgrounds. These playgrounds are mostly in

neighborhood areas. There are neighborhood areas

where colored families live, and neighborhood areas

where white people live, we try to establish them in

that manner, and, then there are certain areas where

they are mixed to a certain extent. We have a play

ground in the Park Extension, and that is a mixed

area for white and colored—a white ~ection and a

colored section—it is mostly white, but there are

several colored sections within several blocks. The

Daffin Park area, mostly around that area is mostly

white. It has occurred, from time to time, that colored

children would play in the Daffin Park area and in

the Park Extension area, but no action had been

taken, because it is legal, it is allowed, and nobody

has said anything about it. The playground areas

are basically for young children, say 15 to 16 and

under, along that age group, we give priority to the

playground to the younger children over the grown

ups, it made no difference as to whether they were

white or colored. Anytime that we requested anyone

to do something and they refused we would ask the

police to stop in, if we would ask them to leave and

they did not we would ask the police to step in. We

have had reports that colored children have played

in the Park Extension, but they were never arrested

or told to leave . . . (R. 42-43).

On cross-examination, Mr. Hager stated in answer to

questions:

I testified that if there was a conflict between the

younger people and the older people using the park

facilities the preference would be for the younger

o ---

people to use them, hut we have no objection to older

people using the facilities if there are no younger

people present or if they are not scheduled to be used

by the younger people . . . (R. 44).

It has been the custom to use the parks separately

for the different races. I couldn’t say whether or not

a permit would or would not be issued to a person

of color if that person came to the office the Recre

ational Department and requested a permit to play

on the courts, hut I am of the opinion that it would

have been, we have never refused one, the request

never has been made . . . (R. 45).

There is no minimum or maximum age limit for the

use of basket ball courts, however, at the present time

we have established a minimum-—a maximum age

limit of 16 years for any playground area.

On redirect Mr. Hager further explained:

On school days these courts and the playground

area at Daffin Park are available for only certain age

groups and they are only used at that time of day

by the schools in that vicinity, it is, more or less,

left available for them, that is the way we have our

recreation setup' . . . (R. 46).

I would like to say that normally we would not

schedule anything for that time of the day because

of the schools using the total area there. The schools

use the area during school hours. The Parochial

School uses it during recess and lunch periods and

also for sport, as also the Lutheran School, and the

public schools bring their students out there by bus

and at various times during school hours all day

long, we never know when they are coming, and they

use Cann Park the same way, I might add . . . (R. 47).

If it was compatible to our program we would

grant a permit for the use of the basketball court in

6 —

Daffin Park to anyone regardless of race, creed or

color, however, at that time of day it would not be

compatible to our program . . . (R. 47-48).

Officer Hillis, the next witness for the State, stated as

follows:

My name is G. W. Hillis. I am a police officer

of the Savannah Police Department, and I was a

member of and on duty with the Savannah Police

Department on or about the 23rd day of January of

this year; I was on duty then and I had on my police

uniform. When I arrived there I saw the defend

ants, they were playing basketball. Officer Thompson

talked to them first, and then I talked to them. I asked

them to leave, Officer Thompson had already asked

them, I heard him ask them. They did not leave, and

they did not stop playing until I told them they were

under arrest. We called the wagon (cruiser). Officer

Thompson told them that they would have to leave, he

told them that at first, and they did have an oppor

tunity to leave after he told them that. He asked

them to leave, and then T asked them to leave after

I saw they wasn’t going to stop playing, and when 1

asked them to 'eave one of them made a sarcastic

remark, saying: “ What did he say, I didn’t hear

him’ ’, he was trying to be sarcastic. When I told

them to leave there was one of them who was writing

with a pencil and looking at our badge numbers.

They all had an opportunity to leave before I arrested

them, plenty of time to have left, but I told them to

leave, they wouldn’t leave and T put them under arrest

. . . (R. 49-50).

I am familiar with the fact that there are schools

in that area, and that children would be out there

in about 15 minutes to play in that area . . . (R. 50).

ARGUMENT I.

Petitioners Argue That the Statute Under Which They

Were Convicted Was Too Vague and Indefinite to

Provide an Ascertainable Standard of Guilt.

In their argument on this point, Petitioners seek to lead

the court to believe that this statute is a statute that has

rarely been used and they base this on the fact that there

is a paucity of appellate decisions involving its construc

tion. As pointed out in the opinion of the Georgia Su

preme Court (R. page 52 at page 56) the crime of un

lawful assembly is itself of common law origin.

To determine whether breach of the peace statutes are

seldom used, I refer the court to the Uniform Crime Re

ports of 1961 printed by the United States Department of

Justice which on page 30 carries Breach of the Peace a>

disorderly conduct in their records. On page 93 the chart

shows that there were 468,071 arrests for disorderly con

duct (Breach of the Peace) made in the United States din

ing 1961. Other than the amount of people arrested for

drunkenness this was by far the most common charge1

placed against individuals. As to whether such a charge

was too vague and indefinite to warrant a conviction,

page 86 of the report shows that there were 62.6% find

ings of guilty against all people arrested for disorderly

conduct and 15.4% acquittals or dismissals. What is

most probably true is that due to the antiquity of the

crime “ Breach of the Peace” , it has rarely been chal

lenged in the Appellate Courts.

In their brief petitioners refer to the case of Samuels v.

State, 103 Ga. Appeals 66, 118 S. E. 2nd 231 (1961), as

being the only Georgia case in which there has been a

construction of this statute. In giving the court the facts

in the Samuels case in order to try and place it within

— 8 —

the bounds of Gamer v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 7 L. Ed.

(2) 207, Petitioners left out what was said on page 66

which came after the fact was shown that they had sat

down at the lunch counter that had been customarily re

served for white people only. “ The personnel of the

store informed the defendants that the lunch counter was

closed, the lights over the counter were extinguished and

the defendants were refused service. This action was

taken because they were Negroes.’ ’ In their opinion the

court said (page 66), “ Several witnesses testified that in

their opinion the presence of the defendants at the lunch

counter would tend to create a disturbance.’ ’ A reading

of the record in the Georgia Court of Appeals (Transcript

of Record, page 19) showed that the witnesses referred to

were the employees of the store, one of whom was a Mr.

Tyson, who stated, “ We had closed the counter and were

no longer serving at that lunch counter. Ordinarily we

would not have closed it up at that time of day. It would

have remained opened normally until 10:00 that night and

it was a result of the defendants being at the counter that

we closed it.’ ’ It was this witness’s opinion that the de

fendants were creating a disturbance. Mr. Kline, the

Manager, also stated that he wanted to keep the counter

closed as long as there was any disturbance and he con

sidered this a disturbance (Ga. Court of Appeals, Tran

script of Record, page 20).

It is significant that Samuels was represented by the

same attorneys who represent the Petitioners in this ac

tion and that they did not make any suggestion that the

statute was unconstitutional.

As the respondent understands the argument of the

petitioners, they are not arguing that the statute was un

constitutionally applied to them but that the statute itself

is unconstitutional as being too vague and indefinite.

— 9 —

We, therefore, cite to the court the case of Chaplinsky

v. New Hampshire, 315 IT. S. 568, 86 L. ed. 1031, which

involved a statute whose stated purpose was to preserve

the public peace. The court on page 573 stated “ The

statute, as construed, does no more than prohibit the face

to face words plainly likely to cause a breach of the peace

by the addressee.” The Petitioner in that case was claim

ing that the statute was limiting his freedom of speech.

This court held that such a statute was not so vague *>nd

indefinite as to contravene the Fourteenth Amendment.

The case of Fox v. The State of Washington, 236 lT. S.

273, 59 L. ed. 573 (1914), involved a violation of a Breach

of the Peace statute. The highest court in the state of

Washington held that the statute was not bad for uncer

tainty. This court, page 277, said, “ We understand the*

State Court by implication, at least, to have read the

statute as confined to encouraging an actual breach of

law. Therefore, the argument that this act is both an

unjustifiable restriction of liberty and too vague for a

criminal law must fail.”

We cite to the court a decision of the Court of Appeals

of New York, People v. Galpern, 259 X. Y. 279, 181 X. E.

572, in which that court held: “ The record shows that

the arrest arose out of a dispute, conducted on each side

quietly and without disorder, between a citizen, in this

ease a member of the bar, who asserted a right to stand

upon the sidewalk of a street in quiet orderly conversation

with a group of friends, and a police officer, who assorted

a right to direct, those who use the sidewalk to ‘ move on'

when in his opinion they were obstructing the sidewalk.”

The defendant was convicted of a Breach of the Peace for

failing to move on. The question involved is very much

similar to the question involved here. On page 573 the

court held “ Even if we should find that the police officer’s

interference was unnecessary, and, in the circumstances.

— 10 —

ill-advised, wo could not find that it was unauthorized.

The defendant, knowing the character and standing of

his group of friends and that they would not willingly

annoy or offend others, might conclude that ‘ he inter

ference was officious; the police officer without such knowl

edge might conclude that it was a useful precaution to

avoid possible disturbance. The law authorized the officer

to use his judgment. Friends may congregate on tin-

sidewalk in an orderly group for a short conversation,

without creating disorder or unduly offending or obstruct

ing others, but they must ‘ move on’ when a police officer

so directs for the purpose of avoiding possible disorder

which otherwise might ensue. The Legislature has pro

vided that failure to obey such direction in itself is dis

orderly conduct. That provision tends to preserve public-

order on the streets of a great city.”

Petitioners’ brief argues that the determination of a

purpose to disturb the public peace is left entirely to tin-

discretion of the police, the courts and the jury (Brief of

Petitioner, page 13). The question is now asked Peti

tioners: To whom would they suggest such a question

should be left if not to the police, the courts and the jury?

There are many cases where a jury and the courts must

determine questions of this character as, for instance,

“ intent” and “ malice” .

The Petitioners in their brief, page 14, further state.

“ If the statute is considered without the benefit of tin-

construction given it in the Samuels case, supra, it could

not be known whether the law covered peaceful and

orderly acts or merely outwardly disorderly conduct.”

This statement answers itself in that the petitioners recog

nize that the Samuels case had previously been decided

and had construed the act so that they are unable to state

that they were not aware of its construction.

— 11 —

This court has again recently held in the case of Gamer

v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 7 L. id. (2) 207, at 216, “ We

are aware that the Louisiana courts have the final au

thority to interpret and where they see fit, to reinterpret

that state’s legislation.” That case also involved the in

terpretation of a breach of the peace statute. This court

on page 215 said, “ WTe, of course, are bound by a state’s

interpretation of its own statute and will not substitute

our judgment for that of the state’s when it becomes

necessary to analyze the evidence for the purpose of

determining whether that evidence supports the findings

of a state court.”

The Petitioners have widened their argument from that

stated in its original heading to the further point that

the petitioners say that they were arrested solely because

they were Negroes. During the trial of the case and on

appeal below, petitioners consistently argued that they had

gone there merely to play basket ball; whereas, the State

of Georgia attacked the bona tides of this statement. At

last on page 15 of Petitioners’ Brief they admit that it

may be regarded as “ a profound, nonverbal expression

of the impropriety of racial segregation in public parks” .

They then argue that this demonstration was within the

range of freedom of speech as assured bv the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Surely taking over the playground does more than ex

press their views and is similar to the sit-down strikes.

The reasoning employed by the court in National Labor

Relations Board v. Fansteel Metal Corporation, 306 U. S.

240, 83 L. ed. 627, expresses the feeling that is applicable

to this case. At page 253 this Court said, “ The em

ployees had the right to strike but they had no license to

commit acts of violence or to seize their employer’s

plant.”

— 12 —

The State of Georgia is not denying the right of Peti

tioners to play upon public playgrounds. There is no

evidence to support a finding that if the children weren’t

assigned the playground, the Petitioners could not have

played. What Petitioners want this court to do is to over

look any and all other evidence in this case except that

they were Negroes and that they were arrested.

There is no evidence to support such a statement as a

“ white basket hall court’ ’. That would mean a basket

ball court reserved exclusively for whites. What the

testimony does show (R. page 44) is that there are play

grounds in white areas and playgrounds in colored areas

(R. page 44). Mr. Hager, Superintendent of the Recrea

tional Department, testified that they tried to establish

them in that manner, that there are two playgrounds that

are in mixed areas. One of them being in Park Exten

sion and the other in Wells Park (R. page 42). Mr.

Hager further testified, “ It has occurred, from time to

time, that colored children would play in the Baffin Park

area and in the Park Extension area, hut no action had

been taken because it is legal, it is allowed, and nobody

has said anything about it’ ’ (emphasis ours) (R. page 43).

I

Officer Hillis stated, “ There have been colored children

in Daffin Park, hut I did not arrest those children, hut I

arrested these people because we were afraid of what

was going to happen. Colored children have played in

Daffin Park and they have fished there” (R. page 42).

The Petitioners on cross-examination sought to develop

that one of the reasons the Petitioners were arrested was

because they were Negroes. This fact, in the policeman’s

eyes, added an additional reason for asking the Petition

ers to leave since they had taken over the childrens’

playground in an area surrounded by whites and there

was, therefore, more cause to recognize a possible dis-

turbanee. The Petitioners themselves now admit that

maybe they weren’t there to play basket ball but that

they were there to put on what they called a demonstra

tion.

The fault in the Petitioner’s reasoning is that they have

not shown that the park was segregated but the state on

its own volition went out of its way to show that it was

not segregated, as witnessed by the testimony of Mr.

Hager, the Superintendent of Playgrounds. In trying to

demonstrate their right to play, the Petitioners took away

the rights of those for whom the playground had been set

aside at that time.

The Petitioners have not shown that the exclusion of

adults from the playground during these hours was an

unreasonable exercise of discretion by the playground

authorities. Petitioners by their precipitate action which

they classify as a protest (Brief of Petitioners, page 22)

could easily have inflamed the public. This court has held

that park segregation is unlawful and rights of minorities

are to be protected but with a right goes a corresponding:

duty that is to obey all reasonable requests of a police

officer. As was said by Judge Lehman writing for the

New York Court of Appeals in People v. Galpern, 2.19

X. Y. 279, 181 N. E. 572, “ Failure, even though consci

entious, to obey directions of a police officer, not exceed

ing his authority, may interfere with the public order

and lead to a breach of the peace.”

- 1 4 -

ARGUMENT n .

Petitioners Further Argue That the Judgment Below

Does ITot Rest Upon Adequate Non-Federal

Grounds for Decision.

In their argument, Petitioners apparently expand this

point to include the same point that is included in and

argued under Argument I above. This is indicated by

their first statement under Argument II, in which they

state: “ Initially it should be emphasized that the court

below indisputably 1 consider and reject petitioners'

due process claim v. the Fourteenth Amendment . . .

by asserting: ‘ However, by applying the well-recognized

principles and applicable tests above-stated, we find no

deprivation of the defendants’ constitutional rights under

the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Consti

tution’. ’ ’ A careful reading of the decision below shows

the statement attributed to the court below was in con

junction with their discussion relating to whether the

statute, under which the Petitioners were convicted, was

so vague the Defendants were not placed on notice as to

what criminal act they committed. As was stated above,

this point was covered in Argument I and for that reason

will not here be gone into again.

The Petitioners here present the question of whether

the court below followed its set rule in treating as aban

doned any assignments of error not insisted upon by

counsel in their briefs or otherwise. Here the discussion

deals with the two assignments of error treated by the

court below as abandoned. In the Petitioner’s bill of

exceptions to the court below these two assignments of

error were on the judgment sentencing each petitioner

(fourth ground) and on the denial of their motion for a

new trial (third ground). In reference to these two

— 13 —

grounds in the court below the Petitioners cited no au

thority, made no argument or even a statement that such

grounds were still relied upon. In view of the foregoing,

the court below applied the applicable rule as laid down

in Henderson v. Lott, 163 Ga. 326 (136 S. E. 403), and

other cases cited in their decision and therefore correctly

treated the questions as abandoned (R. 54).

We recognize that this Court will inquire into the ade

quacy of a decision on state procedural grounds to deter

mine whether the procedural application involved was

inconsistent with prior decided cases. Staub v. City of

Baxley, 355 U. S. 313. Even in the face of the above clear

rule the Petitioners have not cited to this Court one

Georgia case to show that the rule laid down in Henderson

V. Lott, supra, has been inconsistently applied.

Petitioners have apparently conceded that the above

Georgia procedural rule has been consistently followed

and therefore have attempted to show that the court be

low should he reversed for two reasons as follows:

1. “ The court below did not exercise due regard for

the general doctrine that every reasonable presumption

is to be indulged against the waiver of a constitutional

right.”

2. In certain cases this Court has found refusals to pass

upon federal issues to be unreasonable for reasons other

than inconsistent procedural application.

The only case Petitioners cite as supporting the first of

the above two reasons is Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S.

60, 70. The Glasser case in no way deals with the deter

mination of a procedural question by a state court, but

rather concerns itself in the referenced part with the ap

pointment of specific counsel to assist Defendant in U. S.

- 1 6 -

District Court over his objection to the appointment. The

holding of the case on this point is clearly stated on page

70. “ To preserve the protection of the Bill of Rights for

hard pressed defendants, we indulge every reasonable pre

sumption against the waiver of fundamental rights.’ ’

We again reiterate that such is not the case here as the

Petitioners had representation by counsel in the court

below, to which representation they had expressed no

objection.

The Petitioners next base their claim for reversal on

what they allege to be an unreasonable refusal to pass

upon federal issues.

We ask, is it unreasonable to be consistent? To ask the

question is to answer it in that inconsistency would lead

to uncertainty and to a lack of knowledge on how to pro

tect one’s rights.

Under the procedural rule involved all that is required

is an insistence on the position taken, that is, let the court

know what position is taken by argument on the question

or by covering the question in the brief or by stating the

assignment of error is insisted upon by counsel.

Petitioners say the above requirement is unreasonable

under the decisions of this court in Staub v. Baxley, 357)

IT. S. 313; Terre Haute I. R. Co. v. Indiana, 104 U. S. 570,

580; Union P. R. Co. v Public Service Commission, 248

IT. S. 67.

These cases are clearly distinguishable from the prin

ciple presented in this case. The Union Pacific Railroad

Company case dealt with the question of whether a consti

tutional right had been waived by complying with the un

constitutional statute. This court in taking jurisdiction

— 17

predicated its action in doing so on duress by the State,

which we submit is not an issue in the current case for

Petitioners w ere afforded every opportunity to present and

argue their case.

Terre Haute Railroad Co. also concerns a point not at

issue here, i. e., untenable construction of a charter granted

by the State and thus evading the Federal question.

In the Staub v. City of Baxley case this court found the

lion-federal grounds to be without any fair or substantial

support and plainly untenable in that the Georgia court did

not follow a long line of its own decisions in determining

the procedural matter. The converse is true in the present

case (R. 54).

Lawrence et al. v. State Tax Commission of Mississippi,

286 U. S. 276, cited by the Petitioners, simply held that

the purported noil-federal ground put forward by the state

court for its refusal to decide the constitutional question

was unsubstantial and illusory. Which is clearly not the

same as the case now before this court.

The decision in the court below does not impede the

assertion of federal rights, nor is it burdensome to require

insistence upon the grounds of appeal. Furthermore, it is

clearly shown that the rule of the court below to treat as

abandoned points not insisted upon has b^en consistently

applied.

It has been held many times by this court that a State

Court has the power to decide the proper method of pre

serving Federal questions and such determination will bind

this Court. Herdon v. Georgia, 295 U. S. 441; Parker v.

Illinois, 333 IT. S. 571; Edelman v. California, 344 U. S.

357; Michel v. Louisiana, 350 lT. S. 91. In all of these cases

this Court deferred to a state court’s determination of its

own procedural rules.

— 1 8 -

CONCLUSION.

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be affirmed.

G. HUGHEL HARRISON,

Assistant Attorney General of Georgia.

P. O. Address:

132 State Judicial Building,

40 Capitol Square,

Atlanta 3, Georgia.

Respectfully submitted.

EUGENE COOK,

Attorney General of Georgia.

ANDREW ,J. RYAN, JR.,

Solicitor General, Eastern Judicial Cir

cuit of Georgia,

SYLVAN A. GARFUNKEL,

Assistant Solicitor General, Eastern

Judicial Circuit of Georgia,

Attorneys for Respondent.

I*. O. Address:

Room 305 Court House,

Chatham County,

Savannah, Georgia.