Affidavit of Alex K. Brock

Public Court Documents

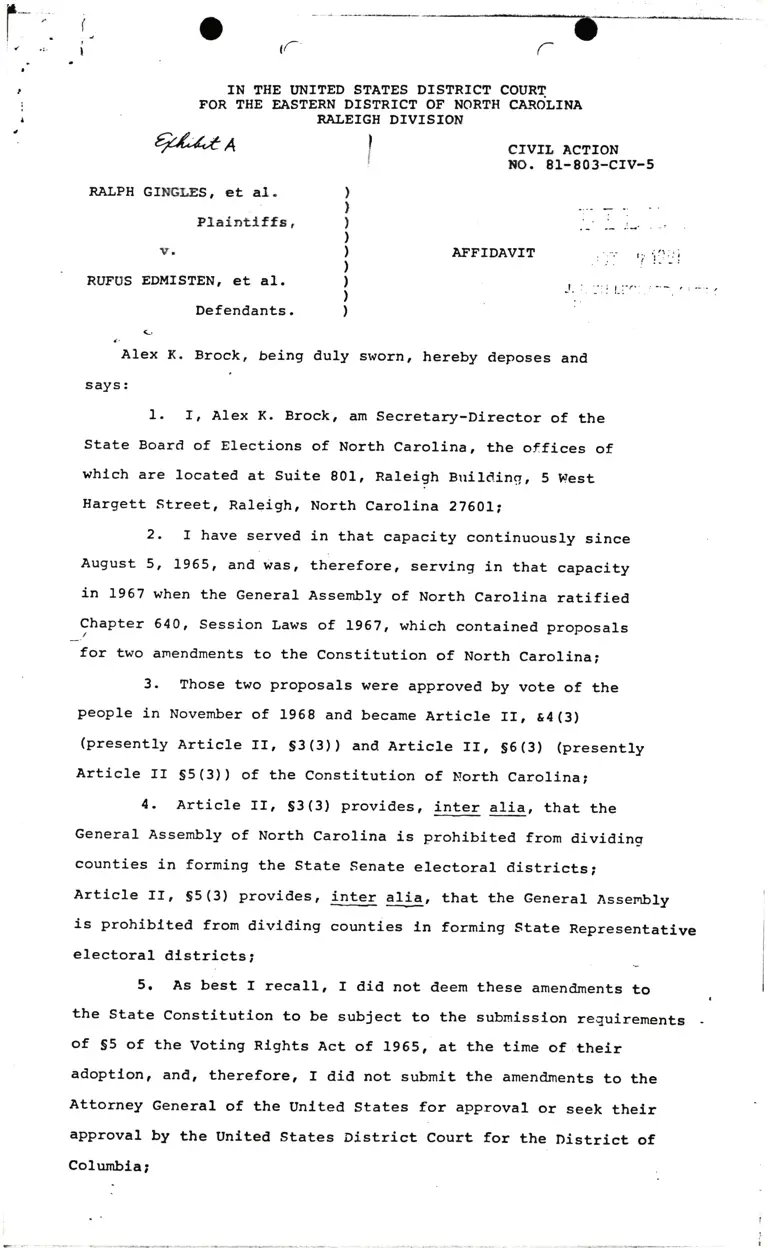

October 6, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Affidavit of Alex K. Brock, 1981. 7126252e-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/71bcb289-eb8a-4250-8b66-6a24ab365609/affidavit-of-alex-k-brock. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

ta

(

,

I

r

,

,

a

qr&,t* e

RALEIGH DIVISION

I

I

)

)

CTVTL AETION

no. 81-803-crv-5

RALPH GINGI.PS, et aI. )

Plaintlffs, I

v.

rN THE T'NITED STATES DISTRICT COURq

POR THE EASTERN DTSTRICT OF NORTH CAROLTNA

)

RUFUS EDMISTEN, et al. )

)

Defendants. )

Alex X. Brock, being duly srdorn, hereby deposes and

says:

1. l, Alex K. Brockr Brn Secretary-Dlrector of the

state Boarcl of Elections of North carolina, the offices of

whlch are located at suite Bo1, Raleigh Brrild.inq, 5 west

Hargett Street, Raleigh, North Caroll-na 276Oli

2- r have served in that capacity continuously since

August 5, L965, and was, therefore, servlng in that capacity

in 1967 when the General Assembly of North Carolina ratified

chapter 640, Session Laws of L967, which contained proposals

for two amendments to the constitution of North carolina;

3. Those two proposals hrere approved by vote of the

peopre in November of 1968 and became Article rr, s4(3)

(presently Article ff, 53(3)) and Article ff, SG(3) (presently

Article rf 55 (3) ) of the ConstitutLon of Dlorth Carolina;

4. ArticLe ff, 53(3) provides, inter alia, that the

General Assembly of North Carolina is prohibited from dividing

counties in forming the state senate electoral districts;

Artlcle ff , 55(3) provides, iptgr a1la, that the General Asserqbly

is prohibtted from dividing counties ln forming State Representative

electoral dLstricts ?

5. As best f recalI, f did not deem these amendments to

the State ConstitutLon to be subject to the submissl.on requirements

of 55 of the voting Rtghts Act of 1965, at the time of.their

adoptLon, and, therefore, r did not submit the amend.ments to the

Attorney General of the Unlted States for approval or seek thelr

approval by the Unlted States District Court for the District of

Columbla i

.

of

on

:

r

I

k

l6

!!tbs".

t ""orn*issLon ExpLres 1* qfo

-2-

6. I have, however, now advl.sed the Attorney General

the 1g5g co'rstLtutional alrendments, by way of correspondence

the dates of Septerober 22, 23, 24 and 28, 1981;

7. A copy of all of my corresPondence to the Attorney

General, regardlng J.n part the 1958 amendments Ls attached'

hereto, along with pertlnent attachments to the corresPondenee,

excluding copLes of sessLon laws, the eorresPondence and attach-

ments belng incorporated herein by reference:

8. I have subnLtted all information to the Attorney General

whl-ch f deerc to be of any Lrlportance or significance to a determina-

tion by him as to whether the amendments satisfy the reggirements

of s5 of the ltoting Rights Act of 1965 and have requested that the

determLnation be made as expedltiously as possible;

g. f have also submitted to the Attorney General, for his

approval, copies of chapter 8oo, chapter 82L, and Chapter 87,

Session Laws of 1981, these constituting, resPectively, North

Carolina's apportionment plans for the state House and Senate'

and state Congressional electoral districts ?

l0.Ihavesubrnittedallotherinformationdeemedbyrne

to be pertinent to the apportionment plans, includinq aII

supplernental information requested by the Attorney General'

01,*H tsr,^L

Alex K. Brock

Secretary-Dl-rector

North Carolina State

Board of Elections

AFFIANT

Sworn to and subscribed before me

this *" 6fu daY of october, 1981.