Jackson v. Marvell School District Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 6, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Marvell School District Brief for Appellants, 1968. 40c990f8-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/723b77e7-1e96-4e35-af30-477c28a0f26b/jackson-v-marvell-school-district-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

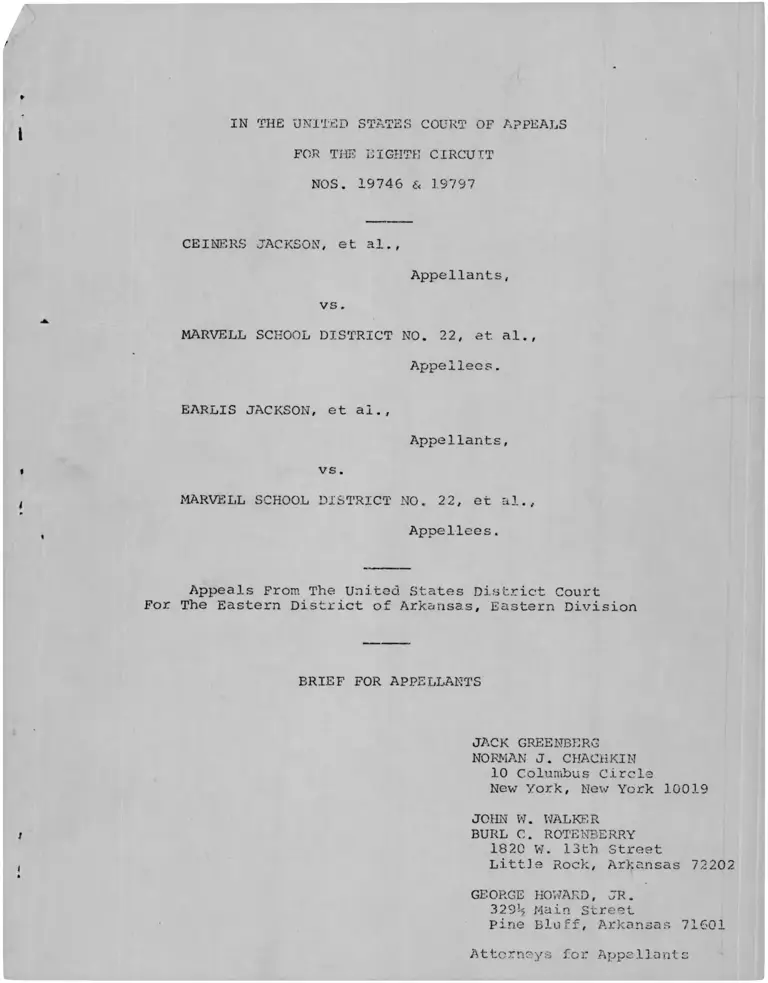

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 19746 £< 19797

CEINERS JACKSON, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.,

Appellees.

EARLIS JACKSON, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeals From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of Arkansas, Eastern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

BURL C. ROTENBERRY

18 20 W. 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

GEORGE HOWARD, JR.

329*5 Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 71601

Attorneys for Appellants

Pa^e

Table of Cases ...................................... ii

Preliminary Statement ................................ iv

Issue Presented for Review ............................ 1

Statement of the C a s e ................................ 2

Argument

The Court Below Erred In Permitting This School

District To Continue To Use Free Choice On The

Ground That Immediate Conversion To A Unitary

System Might Result in The Withdrawal of White

Students From The Public Schools . . 15

Conclusion............................................. 27

INDEX

x

Page

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958)............ 17

Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., No. 26432

(5th Cir., April 15, 1969).................... 18 :

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954)............ 2, 23

Cato v. Parham, 293 F. Supp. 1375 (E.D. Ark. 1968) . . . . 23

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F.2d 661

(8th Cir. 1966) .............................. 24

Coppedge v. Franklin County Bd. of Educ., 404 F.2d

1177 (4th Cir. 1968).......................... 26

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960)............ 5

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) ........................ 19

Felder v. Harnett County Bd. of Educ., No. 12,894

(4th Cir., April 22, 1969).................... 26

Gaston County, North Carolina v. United States,

___ U.S. ___, 23 L.ed. 2d 309 (1969) .......... 5

Gilbert v. Hoisting & Portable Engineers, 237 Ore.

139, 390 P. 2d 320 (1964)...................... 23

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) .......................... 3, 8, 19

Hall v. St. Helena parish School Bd., No. 26450

(5th Cir., May 28, 1969)...................... 20

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County,

No. 19404 (8th Cir., May 9, 1969) ............ 19, 20

Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, 389 F.2d

740 (8th Cir. 1968) .......................... 2, 3, 21,

23, 24

Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist. v. Evers,

357 F. 2d 653 (5th Cir. 1966).................. 5

Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas School Dist. No. 22,

378 F. 2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967).................. 3, 5

Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas School Dist. No. 22,

297 F. Supp. 753 (E.D. Ark. 1969) ............ 18, 19, 22

Table of Cases

ii

Page

McNeese v. Board of Educ., 373 U.S. 668 (1963).......... 15

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S.

450 (1968).................................... 3, 18

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Bd., Civ. No.

15556 (E.D. La., July 2, 1969)................ 19

Newman v. Piggie park Enterprises, Inc., 390

U.S. 400 (1968) .............................. 23, 25

Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) . . '3, 18

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R.R., 186 F.2d 473 (4th

Cir. 1951) .................................. 26

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968) ........ 25

Sprague v. Taconic Nat11 Bank, 307 U.S. 161 (1939) . . . . 23

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Bd. of Educ., 318 F.2d

425 (5th Cir. 1963), 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir.

1964), 387 F. 2d 486 (5th Cir. 1967) .......... 5

Thomas v. west Baton Rouge parish School Bd., civ.

No. 3208 (E.D. La., July 25, 1969)............ 19

Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 724 (S.D. Ga. 1965) . . . 9

United States v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer, 396

F.2d 44 (5th Cir. 1968) ...................... 20

United States v. Choctaw County Bd. of Educ., No.

27297 (5th Cir., June 26, 1969) .............. 20

United States v. Hinds County Bd. of Educ., No.

28030 (5th Cir., July 3, 1969)................ 18-19

United States v. Lincoln County Bd. of Educ., Civ.

No. 1400 (S.D. Ga., July 9, 1969) ............ 5

Vaughn v. Atkinson, 369 U.S. 567 (1962) ................ 23

Walker v. County School Bd. of Brunswick County, Va.,

No. 13,283 (4th Cir., July 11, 1969).......... 18

1

Preliminary Statement

These are appeals from the unreported orders of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas, Eastern Division, Hon. Oren Harris, United States

District Judge, entered April 15, 1969 and June 13, 1969.

iv

r>

H I

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 19746 & 19797

CEINERS JACKSON, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.,

Appellees.

EARLIS JACKSON, et al.,

vs.

Appellants,

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeals From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of Arkansas, Eastern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issue Presented For Review

Whether the District Court erred in rejecting a deseg

regation plan which would immediately convert the Marvell public

schools into a unitary nonracial school system, because of the

possibility that white students might thereupon withdraw from

the system.

Statement of the Case

This is not the first time that this Court has been

called upon to review the lack of progress of the Marvell School

District in eliminating its dual school system based on race. When

appellants commenced the first of these actions"^ August 17, 1966,

more than twelve years had passed since the decision in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) but the school district

had never voluntarily undertaken even the most minute step toward

2/converting to a unitary school system.— in 1968 this Court

declined to rule out freedom of choice on the basis of the limited

record before it but did require greater affirmative action by

appellees to eliminate their dual system. Jackson v. Marvell

School Dist. No. 22, 389 F.2d 740 (8th Cir. 1968).

During the pendency of the first appeal, the second

3/action was commenced. in that case, appellants sought to enjoin

additional construction on the site of the (all-Negro) Tate High

School by the district, on the grounds that such construction would

perpetuate the dual school system based on race (Complaint in No.

H-67-C-20, 55 II, XI-/)

1/ Ceiners Jackson, et al. v. Marvell School District No. 22, et al., civ. No. H-66-C-35 (E.D. Ark., E.D.).

2/ In 1965, the district agreed to allow free choice in grades 1-4

during the 1965-66 school year in accordance with then current

H.E.W. Guidelines in order to retain its federal funds. Jackson v

Marvell School Dist. No, 22, No. 18762 (8th Cir.), Record, pp. 5-6,* 8—9 .

3/ Earlis Jackson, et al., v. Marvell School District No. 22, et al., Civ. No. H-67-C-20 (E.D. Ark., E.D.).

4/ On July 14, 1969, this Court granted appellants' motion to proceed upon the original papers herein.

5/ The Complaint alternatively prayed, should construction be

-2-

/

Subsequent to the May 27, 1968 decisions of the United

States Supreme Court in Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430; Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391

U.S. 450; and Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443, and

after remand by this Court, Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22,

supra, plaintiffs in the original action filed a Motion for Further

Relief seeking to require that the district adopt and implement a

plan of desegregation other than a freedom of choice plan (Motion

for Further Relief, No. H-66-C-35). The two actions were consol

idated at the August 6, 1968 hearing (Tr. I 4;-^ Order entered

August 29, 1968, p. 2). This appeal is taken from the June 17

order of the district court approving continued free choice in

this school distict.

The district

Marvell School District No. 22 has operated under

freedom-of-choice plans for four school years. The following

table shows the results of the choice periods in those years:

permitted, for relief consistent with Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas

School Dist, No. 22, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967). The request for

injunction was subsequently withdrawn because construction had been

completed, and appellants stated that they would rely on their

prayer for alternative relief consistent with Kelley. (Letter from

undersigned counsel to Hon. Oren Harris, U.S. District Judge, dated

September 14, 1967, in No. H-67-C-20).

6/ Appellants have previously furnished the Court, at the time of

filing their Motion for Summary Reversal in No. 19746, certified

copies of the transcripts of the hearings below. The transcript of

the August 6, 1968 hearing is in two volumes and will be referred

to herein as Tr. I and Tr. II respectively; the one-volume trans

cript of the March 31, 1969 hearing will be referred to as Tr. III.

-3-

Year

Total

Negro

Stu

dents in

District

Number of

Negro Stu

dents in

"white"

Schools

% of

Negro Stu

dents in

"white"

Schools

Number of

white Stu

dents in

All-Negro Schools

% of

white stu

dents in

All-Negro Schools

7/1965-66- 1,700 17 1.0 % 0 0.0 %

8/1966-67- 1, 700 116 6.8 % 0 0.0 %

1967-68 1,566 207 13.2 % 0 0.0 %

1968-69 1,616 205 12.7 % 0 0.0 %

9/1969-70- 1,548 215 13.9 % 36 6.6%

The district presently operates the predominantly white Marvell

High School (opened in 1967-68) and Marvell Elementary School,

the all-Negro Tate High and Elementary Schools, and the Turner

School, a small, rural all-Negro elementary school

Marvell High and Marvell Elementary are about two blocks apart

and the Tate Schools are less than a mile away, also within the

town of Marvell (Tr. Ill 40).

7/ Grades 1-4 offered free choice.

8/ Grades 1-6, 11-12 offered free choice.

9/ Based on choices exercised to May 16, 1969.

10/According to the May 22, 1969 Report of the district, Tate

Elementary School will have thirty-six white students enrolled

during 1969-70; the Turner School will be closed and students who

chose it permitted to attend Tate or Marvell Elementary.

11/During the school year 1965-66, the district operated the white

Marvell Elementary and High schools on the present Marvell Elem

entary site (transfer of the predominantly white high school grades

to the newly constructed facility in 1967-68 left unused facilities

in Marvell Elementary; see Answers to Interrogatories in No. H-67-

C—20), the Negro Tate Elementary and High Schools on a single cam

pus at the present location, and three small Negro elementary

schools in rural locations. 389 F.2d at 742-43. One small all-

Negro school was closed prior to the 1966-67 school year and another

prior to the 1967-68 school year, leaving only Turner. (Answers to Interrogatories in No. H-67-C-20).

-4-

The Proceedings

Following the filing of the Motion for Further Relief

and consolidation of the two actions, an evidentiary hearing was

held on August 6, 1968. The district called its Superintendent

(Tr. I 6-107; Tr. II 3-24) and appellants called Dr. Myron Lieber-

12/man— as an expert witness. In general, the Superintendent

defended the district's record under freedom of choice, on the

grounds that every choice made had been honored, that in his

judgment the majority in both the white and Negro communities

favored free choice, that it was an educationally sound procedure,

that forced interracial association in the classroom was not

conducive to learning, that there was an achievement differential

between Negro and white students in the district— ^ that made any

plan but freedom of choice impossible, and that any plan other

than freedom of choice would result in the desertion of the dis

trict's white patrons and pupils.

12/ Dr. Lieberman testified as an expert witness for plaintiffs

in Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas School Dist. No. 22, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967).

13/ To the extent that this is an accurate statement of fact it

is the direct result of the inadequate segregated education

offered Negro children by this district. For example, the Answers

to Interrogatories in No. H-67-C-20 demonstrate that tie black

schools in the district had lower sq. ft./pupil ratios, higher

pupil/teacher ratios and higher pupil/bus route ratios than the

white schools. This was not the ground upon which the district

court sustained free choice, as he clearly could not have done.

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960); Jackson Municipal

Separate School Dist. v. Evers, 357 F.2d 653 (5th Cir. 1966);

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Bd. of Educ., 318 F.2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963),

333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964), 387 F.2d 486 (5th Cir. 1967); United

States v. Lincoln County Bd. of Educ., Civ. No. 1400 (S.D. Ga.,

July 9, 1969); cf. Gaston County, North Carolina v. United States,

___ U.S. ___, 23 L.ed.2d 309 (1969) . The separate and duplicative

bus routes serving Tate and Marvell schools were redrawn by the

district after a May, 1968 pretrial conference at which counsel

displayed a map of the overlapping segregated routes.

Dr. Lieberman stated that his analysis and study of

the district led him to conclude that the basic organization and

operation of the district were dictated by racial considerations,

that the duplication of facilities and inefficiency of operating

two separate twelve-grade schools in a district this size was so

devoid of educational purpose or justification that the rationale

could only be racial, that freedom of choice would never work to

eliminate the dual school system in this district, and that other

means of converting to a unitary school system were readily avail

able to the district. Specifically, Dr. Lieberman proposed pairing

and grade restructuring so that all students, Negro and white,

residing within the district, would attend the present Tate schools

for the elementary grades; Marvell Elementary would serve as a

junior high school; and the high school grades would be located

at the new Marvell High School. Dr. Lieberman felt that the

14/district could implement his plan in a few days— ■ and that it

promised immediate conversion to a unitary system offering better

education to all students of the district.

Although the district court agreed that freedom of

choice had shown itself worthless to break down the institutional

barriers of the segregated school system in Marvell, it rejected

Dr. Lieberman's estimate of the ease with which another plan

could be implemented, and announced that because so little time

15/remained before the opening of school for 19 68-69— ! free choice

14/ Tr. II 44-46.

15/ At the May 3, 1968 pre-trial conference, the district court

refused to set a trial date after appellants announced their intention to challenge the district's free choice plan, on the

ground that cases raising the issue were pending before the United

-6-

1

would be permitted for another year:

Here we have an important school program

in a transitional state at a time when

our circuit has suggested this Court

recognize that there should be some time

and opportunity in this transitional

period for the development of a consti

tutional desegregation program. The

thing that bothers me is just what the

court itself recognized, that there are

school boards and districts which simply

do not come to the reality of developing

the kind of a program that would be ac

cepted and approved and would provide the

objective which the Court said fourteen

years ago that we must come to ultimately

to do justice to all of those who are en

titled to an equal opportunity for public

education. So consequently the Circuit

Court of Appeals and this Court has given

an opportunity to this school district

for compliance, and I for one was hopeful

that the proposed plan for freedom-of-

choice would prove to be effective. . . .

. . . If you've got something that doesn't

work then we better look for something

else, and that is precisely what this Court

is going to do.

It is quite obvious to me that the freedom-

of-choice system is not working for this

district. It is clear from the testimony

and the record presented here that it will

not work, that you are not going to resolve

this problem with this kind of program. . . .

. . . I am therefore going to cancel and

disapprove your porposed desegregation

plan of freedom-of-choice. . . .

. . . This is the 6th of August. To leave

the school district in that kind of a sus

pended situation at this time would, in my

judgment, be cruel and certainly unjustified.

So the Court is going to permit the school

district to proceed with the school program

under the present arrangement beginning with

the school system.

States Supreme Court. Yet no hearing was held between May 27, 1968,

when those cases were decided adversely to free choice, and August

6, 1968.

-7-

Then I am going to ask that by February the

1st that you submit another type of plan be-

cause l_ am saying that for this school district

under the circumstances freedom-of-choice

is out the window. There is no need to

pursue a course that has already run out and is no good.

(Tr. II 110-11, 113, 114, 116 [emphasis supplied]). The district

court thereafter entered its written order August 29, 1968,

allowing the district until February, 1969 to submit a plan other

, 16/ than freedom of choice.—

At this point, appellants were disappointed by the

district court's failure to require a unitary school system in

1968-69 but fully expected that compliance with the Constitution

would be achieved by 1969-70. Except for the effective date of

17/the district court's order,— there was nothing to appeal,

although nothing concrete had been achieved, either.

16/ The order provided, inter alia:

2. The Plan of Desegregation of Marvell

School District No. 22 proposed on No

vember 25, 1966, and amended April 9, 1968,

is hereby disapproved as an unacceptable

method for the operation of this school

on a constitutional basis as interpreted

by the Supreme Court in Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County (No. 695

decided May 27, 1968).

3. The defendants are hereby ordered to

propose an alternate plan for the conver

sion of the school system to a unitary sys

tem in accordance with the decisions of

the Supreme Court made May 27, 1968, for

all students in attendance, and such plan

shall be presented to the Court on or be

fore E’ebruary 1, 19 69. Upon the filing

of said plan with the Court and after due

notice, a hearing will be held at a day

certain to be determined by the Court.

(Order entered August 29, 1968, p. 2) .

17/ Compare Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas School Dist. No. 22,

-8-

Appellees' "Report" filed February 1, 1969, however,

failed to comply with the district court's direction. it stated

that freedom of choice is the only feasible procedure in the

assignment of students in this system; there is no feasible al

ternative" (Report of Defendants dated January 31, 1969, p. 1).

Appellants filed a Motion February 21 opposing continued free

choice and praying that the district be given five days in which

to submit a new plan, failing which a receiver be appointed by

the court to operate the schools in accordance with the Constitu-

4. • Wtion. The district court scheduled a hearing March 31, 1969.

Appellees presented testimony by the Superintendent

(Tr. Ill 6-48), the Mayor of Marvell (Tr. ill 48-66) and two

Negro schoolteachers employed by the district (Tr. Ill 66-87). The

Superintendent testified that the District had rejected alter

natives other than freedom of choice because while in each instance

they would achieve total integration and conversion to a unitary

system, a withdrawal of white students from the Marvell public

schools was anticipated:

Q. But really, I just want to captalize [sic]

this, you are making your request for ad

ditional time, and your request for per

mission to continue with freedom of choice

primarily because of the disproportions of

blacks to whites in the school district,

is that correct. That is to say that you

have too many Negroes in the school system

and too few whites to make integration

8th Cir. No. 19419 (Motion for Summary Reversal denied September 16, 1968) .

18/ Cf. Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 724 (S.D. Ga. 1965).

-9-

/ !

attractive to white parents and their children.

A. in one immediate shot?

Q. Yes.

A. Yes. The school is based on acceptance

of the people in that community. if you

are going to destroy or chase people out

and cause them to abandon their school,

then the responsibility of the local

people is to keep their schools for the students.

(Tr. Ill 22-23). See also, Tr. Ill 19-20. 26-27, 30-31; cf. Tr

Ill 39. Both the Superintendent and the Mayor explained the "new

approach" to freedom of choice which they felt the district was

proposing, and in which the city government was apparently

cooperating efforts by the school district to encourage white

parents to choose . . 19/all-Negro schools. The new approach did not

promise immediate or speedy conversion to a unitary system;

Q. Is it fair to say that if you have not

been able to get white pupils to transfer

to the black schools under the freedom of

choice, in any numbers anyway, to transfer

to the black schools this next year?

A. That is something that I would be guessinq at.

Q. I understand that.

A. In any great numbers?

Q. Yes.

A. I do not believe that the first shot of

integrating a school is going to be

made with any great degree of enthusiasm.

19/ Apparently the district was satisfied with the rate of choice

of white schools by Negro students, even though that figure

̂ static at less than 14%. (The increases between 1965-66 and

967-68 are misleading. The first year students in all grades were offered free choice was 1967-68. See p. 4 supra.)

-10-

/ T! 1

Q. So if any white students accepted your

offer or invitation it would be token more

or less, would it not, a few white pupils?

A. I think the first step, yes, sir, would be

to get a few.

Q. How long do you propose, in case the court

grants your request, to operate under the

freedom-of-choice procedure, or the

solicitation procedure?

A. Well, of course, we feel like if the begin

ning is made that that foundation could

be built on.

(Tr. Ill 17-18).

The two Negro schoolteachers, employees of the district,

called by appellees, testified that from their knowledge and

experience as well as personal preference, freedom of choice was

a better method of desegregation than forced association through

pairing or zoning. They opined that the majority of the Negroes

in the Marvell school district favored free choice.

Appellants presented no testimony but took the position

that white reluctance or resistance was irrelevant and that the

district had not met its burden of demonstrating that free choice

was an effective means of converting to a unitary system. The

district court recognized that the situation in March was unchanged

from the situation in August:

. . . However, the school district is

still operating at this time a state-

imposed dual system. No progress has

been noted in the disestablishing of

the Negro school as such. . . .

(Tr. II 101).

-11-

But the court now reversed its earlier ruling to hold

that this new variant of freedom of choice should be given an

20/opportunity-- to prove itself:

There were many of us in the Congress

at the time [May 17, 1954] who felt

that the [Supreme] court arbitrarily

went way out in left field to change

the basic law which the Supreme Court

had enunciated in 1896. . . .

. . . I have made it very clear that

as long as those who have the respon

sibility will undertake to bring about

compliance, it may be the impact is

greater on some than on others, but as

long as there can be shown an effort

towards bringing about compliance with

the basic constitutional requirements,

I have great compassion and sympathy

and I am going to do what I can as the

court to assist the leadership and encouragement towards a constitutionally

operated system. . . . When it is

apparent that there is no real effort

being made to bring about better methods

and means of compliance, this court is

directed to act with this kind of

situation. . . .

. . . I want to compliment those who

have the responsibility in this diffi

cult problem. I can see a decidedly

changed attitude of the people through

out the school district who have children

and interested in their education . . . .

Of course, the best solution, if it could

be done, would be to have an all high

school where everyone would be assigned and

an all elementary school. . . .

From the testimony, it is apparent that

through efforts of the mayor, members of

the city council and other leaders in the

school district, the novel approach proposed

might provide a solution of this most

sensitive problem.

20/ Years?

-12-

So since there appears to be a good-faith

effort in the proposal and the court being

persuaded that with the proper guidance

and leadership and understanding, patience

and tolerance, real progress can be realized,

I am going to give the district an oppor

tunity. . . .

I am going to modify my previous ruling

in which I disapproved the continuation of

freedom of choice in the operation of the

schools of this district, at least for the

time being, in an effort to see just how

the proposal of the district will now work.

If, from the reports, no progress is indi

cated and there is no prospects of achieving

a constitutionally operated school system,

the court will have to take notice and act

accordingly. After the results are reported

about May 15 and should it become necessary

for the court to consider this problem in

a different light, the parties will be given

another opportunity to be heard. . . .

Now the court is going to approve this pro

cedure at the risk of being reversed by the

Circuit Court of Appeals. . . .

(Tr. Ill 99-101, 105-09)[emphasis supplied]. Accordingly, the

district court April 15, 1969 entered its order requiring the

district to hold a special choice period between April 15 and

May 15, 1969, and to report the results thereof to the district

court on or before May 22, 1969, after which time the court would

21/pass upon the continued use of freedom of choice.— 1

21/ April 24, 1969, appellants filed a Notice of Appeal from this

order, which was docketed as No. 19,746. Appellants filed a

Motion for Summary Reversal on May 17, 1969, which was denied June

6 "without prejudice to renew after the filing of any additional

order as contemplated in the District Court's order of April 15,

1969."

-13-

May 22, 1969, appellees filed a Report with the district

court which indicated the following results of the special choice

period:

School

Number

white stu-

dents choosing

Number

Negro stu-

dents choosing

Number faculty

bers of minority

race assigned

Marvell Elementary 251 117 0

Marvell High 261 98 1

Tate Elementary 36 660 4-2/3

Tate High 0 628 2-2/3

22/Turner Elementary-- 0 45 0

Total Number of Negro students choosing . . .

Total Number of white students choosing . . .

No. of Negro students choosing "white"

schools ..............................

No. of white students choosing all-

Negro schools ........................

% of Negro students in "white" schools . . .

% of white students in all-Negro schools . .

% of Negro students in all-Negro schools . .

1548

548

215

36

13.9 %

6.6 %

43.5 %

Without further hearing, the district court entered an order

approving the use of freedom of choice for 1969-70 because it

would "produce the maximum degree of desegregation possible at this

time when compared to the reasonably predictable results of other

alternatives." June 17, 1969, appellants filed Notice of Appeal.-^/

22/ The school district proposed to close Turner and offer its

Negro students a second choice between Tate Elementary and

Marvell Elementary Schools.

23/ The appeal was docketed as No. 19797. June 26, 1969, appel

lants filed a Motion to Consolidate Nos. 19746 and 19797, to

Proceed Upon the Original Papers, and for Summary Reversal. On

July 14, 1969, this Court denied summary reversal and remand, but

directed that the matter be set for oral argument and submission

at the September, 1969 session, and established an accelerated briefing schedule.

-14

ARGUMENT

The Court Below Erred In Permitting This

School District To Continue To Use Free

Choice On The Ground That Immediate

Conversion To A Unitary System Might

Result in The Withdrawal of White Students

From The Public Schools

Appellants' chagrin at the present status of the Marvell

School District No. 22 can hardly be described. Three years

after they first filed suit, the Marvell schools will be opening

under the same inefficient and discriminatory-^/ freedom of choice

plan in 1969-70, with the same racially identifiable black and

white schools staffed by racially identifiable faculties. Over a

year after the Supreme Court of the United States declared that

free choice plans were not constitutional means of pupil assignment

in New Kent County, Virginia, where only 15% of the Negro school-

children attended integrated schools, or in Gould, Arkansas, where

less than 15% attended integrated schools, the court below approved

continued free choice in the district despite the evidence that,

25/at best, 13.9% of the district's Negro students would attend

24/ It is habitual for school board counsel in these cases to main

tain that there has been honest and nondiscriminatory admini

stration of the free choice plan by the district. That is not the

sense in which we use the term here. We refer rather to that inher

ent characteristic of freedom of choice which places the burden

upon Negroes to bring about the conversion to a unitary nonracial

school system. Under free choice, Negro schoolchildren must

shoulder that burden despite the indignity of racially identifiable

schools. These children also find themselves isolated by the

district's failure to take steps now to create the unitary school

system which it would have established but for racial discrimination

To maintain that the school district's obligation ends with mechan

ical granting of all choices looks back to the concept of exhaustion

of administrative remedies, cf. McNeese v. Board of Educ., 373 U.S.

668 (1963), and ignores the close relationship between the dual

racial system of education and the "peculiar institution" outlawed by the Thirteenth Amendment. See, Blaustein, A. & Zangrando, R., ed

Civil Rights and the American Negro (1968) 180-322.

-15-

formerly all-white schools, and 6.6% of the district's white

students will attend a formerly all-Negro school. And finally,

appellants have seen their efforts of a year ago, which seemed

close to fruition when the district court required submission of

a new plan, stand for naught as the district court yielded to

the repeated entreaties of the school district not to upset the

whites in the district.

To make matters worse, there is not even the prospect

that the regime approved by the district court will result in a

unitary system in the foreseeable future. To the contrary,

appellees have never maintained that it will, and the district

court has no illusions:

Q. How long do you propose, in case

the court grants your request, to

operate under freedom-of-choice

procedure, or the solicitation

procedure ?

A. Well, of course, we feel like if

the beginning is made that that

foundation could be built on.

(Superintendent Cowsert)(Tr. Ill 18).

. . . of course, the best solution, if

it could be done, would be to have an

all [-district] high school where everyone

25/ The district's 1969-70 estimates are based on choice forms

returned as of May 15, 1969. The table attached to the May 22,

1969 Report shows some 48 Negro students, exclusive of graduating

seniors, who attended the all-Negro Tate and Turner Schools last

year, had not returned their forms. Since the percentage of Negro

children in formerly all-white schools has been stable (extrapola

ting from the figures for years when free choice did not extend to

all grades), it seems highly unlikely that the choices of these 48

will raise the percentage this year significantly, if at all. It

is of course unlikely that the Negro students who chose the Turner

School will on their second choice elect the predominantly white

Marvell Elementary School.

-16-

would be assigned and an all [-district]

elementary school. . . .

(Judge Harris)(Tr. Ill 105-06). Free choice was approved not

because it would work, much less because it could work most

effectively of any plan suggested, but because the district

raised the specter of "white flight" to delay realization of

appellants' constitutional rights.

Q. But really, I just want to captalize [sic]

this, you are making your request for ad

ditional time, and your request for per

mission to continue with freedom of choice

primarily because of the disproportions of

blacks to whites in the school district, is

that correct. That is to say that you have

too many Negroes in the school system and

too few whites to make integration attrac

tive to white parents and their children.

A. In one immediate shot?

Q. Yes.

A. Yes. The school is based on acceptance of

the people in the community. If you are

going to destroy or chase people out and

cause them to abandon their school, then

the responsibility of the local people is

to keep their schools for the students.

(Tr. Ill 22-23). See also, Tr. Ill 19-20, 26-27, 30-31; cf. Tr.

Ill 39; Response to Motion for Permission to Appeal Upon the

Original papers and to Consolidate Appeals, and in Opposition to

Motion for Summary Reversal, p . 5.

White hostility has never been accepted by the federal

courts as a ground for delaying the implementation of constitu

tional rights. This Court early held that such rights were para

mount. Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958). What is so

disheartening about the district court's action in this case is

that the same arguments, in the same context of free choice plans,

were made to and rejected by the Supreme Court of the United

-17-

States in Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, supra, and in Monroe

v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, supra, 391 U.S. at 459:

We are frankly told in the Brief that

without the transfer option it is

apprehended that white students will

flee the school system altogether.

"But it should go without saying that

the vitality of these constitutional

principles cannot be allowed to yield

simply because of disagreement with

them." Brown II at 300.

Accord, Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., No. 26432 (5th

Cir., April 15, 1969); Walker v. County School Bd. of Brunswick

County, Va., No. 13,283 (4th Cir., July 11, 1969); Kelley v.

Altheimer, Arkansas School Dist. No. 22, 297 F. Supp. 753, 758

(E.D. Ark. 1969). "White flight" is an insidious argument. Once

accepted, it can be used as a sort of perpetual procrastinator of

26/constitutional rights. If whites have not learned to accept

the idea of integration between 1954 and 1969, what prospect is

there that they will be any more receptive by 1984? (Instructive

in this regard is the failure of this district to act between

1954 and 1965). Furthermore, it is an extremely slippery concept,

difficult to either prove or disprove. It is baldly asserted by

school administrators who desire to maintain free choice, but it

remains a speculative fancy. It was recently rejected by the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit even when

sought to be supported by "impartial public opinion surveys."

United States v. Hinds County Bd. of Educ., No. 28030 (5th Cir.,

26/ The same argument was proffered by the El Dorado School District

and accepted by the same district judge, to excuse that system's

failure to eliminate its segregated elementary schools. See Kemp

v. Beasley, No. 19782, pending in this Court.

-18-

July 3, 1969), preliminary slip opinion at pp. 6-8. Finally, as

this Court has recently emphasized, the constitutional right to

equal protection of the laws is not subject to the vote. Haney

v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County, No. 19404 (8th Cir., May

9, 1969), slip opinion at pp. 9-10. This principle adheres whether

the vote is with the ballot or with the body, by a change of residence.

The decision below is equally unsupportable on any

other grounds. It is directly contrary to Green because it rejects

what even the court below recognized (Tr. Ill 105-06) to be the

most effective plan to eradicate the dual system based on race.

The appellees had more than sufficient opportunity to develop

their own plan to accomplish that purpose. When they did not,

the district court should have entered its own plan, or that

recommended by appellants' expert witness. See Moore v.

Tangipahoa Parish School Bd., Civ. No. 15556 (E.D. La., July 2,

1969); Thomas v. West Baton Rouge parish School Bd., Civ. No.

3208 (E.D. La., July 25, 1969); Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas

School Dist. No. 22, 297 F. Supp. 753 (E.D. Ark. 1969); cf,

Dowe11 v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971, 972 (W.D.

Okla. 1965).

Appellees are bound to argue that free choice is

resulting in acceptable progress towards a unitary system in

this district, pointing to the 1.2% increase in Negroes attending

white schools this year, and the 6.6% white students who chose

the Negro elementary school; and representing that all Negroes

at Tate Elementary will be attending an "integrated school" next

year. Even under this view of the facts, 43.5% of the Negro

19-

students in this district will continue to attend a segregated,

all-Negro school.

But this Court has recently said that "the time for

transition has now passed and that these problems should have

been worked out long ago." Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier

County, supra, slip opinion at p. 11. Another Circuit has held,

"As a matter of law, there must be student desegregation now,

not 10 per cent in 1968-69, 20 per cent in 1969-70, and so on

until desegregation eventually is effected," United States v.

Choctaw County Bd. of Educ., No. 27297 (5th Cir., June 26, 1969),

slip opinion at p. 9. The district court accepted such a schedule

because it erroneously concluded that good faith vel non satisfied

the Constitution:

. . . I have made it very clear that

as long as those who have the respon

sibility will undertake to bring about

compliance, it may be the impact is

greater on some than others, but as

long as there can be shown an effort

towards bringing about compliance with

the basic constitutional requirements

I have great compassion and sympathy

and I am going to do what I can as the

court to assist the leadership and

encouragement towards a constitutionally

operated system.

(Tr. Ill 100-01).

"At this very, very late date in the glacial movement

toward school racial integration, it should no longer be an

issue of good faith," United States v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer,

396 F.2d 44, 49 (5th Cir. 1968); accord, Hall v. St. Helena

Parish School Bd., No. 26450 (5th Cir., May 28, 1969), slip

-20-

opinion at p. 16. Cf. Kemp v. Beasley, 389 F.2d 178, 185 n.10

(8th Cir. 1968) and accompanying text. At any rate, the record

here completely belies any claim of good faith. Between 1954

and 1965 the district failed to make a single move to eliminate

segregation. It did so only when prodded by H.E.W. in 1965. It

then withdrew in 1966 rather than substantially dismantle its

dual system, and whatever further measures have been effected are

due to the pressure of appellants and court orders. The district

waited until nine days before the last hearing in this matter —

well after it proposed on February 1 to continue free choice —

to send out the letter to white parents soliciting choices of the

Tate Schools (Tr. Ill 9). Even then, as noted, the response was

uninspiring. Furthermore, the district very clearly has acted

in' bad faith with regard to faculty desegregation. Despite this

Court's instruction on February 9, 1968 that "the Board should

be required to take affirmative action to (1) encourage voluntary

transfers . . . (2) assign members of the faculty and staff from

one school to another," Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22,

supra at 745, no such teacher assignments have ever been made

"against their wishes" (Tr. Ill 13).

This Court should require the Marvell district to imple

ment a unitary system now. 27/ There is in this record a plan for

27/ Contrary to appellees' representations, appellants' complaint

is not the lack of racial balance in the Marvell public schools.

Our dissatisfaction lies with the continued operation of a dual

school system in Marvell, which freedom of choice shows no prospect

of eliminating in the foreseeable future. We do contend that the

lack of substantial integration in the classes of this district

demonstrates the futility of freedom of choice, and reflects the

continued existence of the dual system based on race. We seek the

-21-

the operation of the Marvell public schools on a unitary nonracial

basis which the district court recognized to be the optimal plan.

It consists of grade reorganization and pairing so that all of

the district's pupils in a particular grade are assigned to the

same attendance center. Under this plan, faculty desegregation

would take care of itself. So would desegregation of the other

aspects of the educational program. See Kelley v. Altheimer, Ark

ansas School Dist. No. 22, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967).

The district court should be specifically instructed to

require implementation of this plan on remand.

Attorneys' Fees

Appellants submit that this district's obstinacy as

manifested on this record makes an award of counsel fees neces

sary. We recognize that no statute explicitly authorizes fees

in a case of this nature. But it is well established that the

federal courts have equitable power to award attorneys' fees

institution of a unitary nonracial system of public education; what

that means can be very simply stated: The district should be

operated, within the limitation of its present physical facilities,

as nearly as possible as it would be operated had racial discrim

ination never been a factor. in this small district it is obvious

beyond any question that, but for race, two twelve-grade schools

within several blocks of each other in the district's largest

community would never have been established. This was the opinion

of appellants' expert witness. The best remedy is to convert to a

single school system, for it is also apparent that were all the

students in the district of the same race, there would be but one

school facility for each grade.

-22-

/ ?1

in appropriate cases. See Vaughn v. Atkinson, 369 U.S. 567

(1962); Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307 U.S. 161 (1939);

Newman v. Piggie park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 n.4

(1968). This power has been exercised in school desegregation

cases. E.g., Cato v. Parham, 293 F. Supp. 1375 (E.D. Ark. 1968).

The main purpose of the American rule generally

disallowing counsel fees is to avoid discouraging use of the

courts for the resolution of bona fide disputes; however, this

purpose is not served by a trial of the issues "where the law

is clear and the facts free from ambiguity." Comment, 77 Harv.

L. Rev. 1135, 1138 (1964). In a case like the instant one,

forcing the plaintiffs below to sue to enforce their rights under

"clear facts and strong recent precedent seems an abuse of the

remedial system." Ibid..

This proceeding is private in form only the plain

tiffs acted as "private attorneys general" in vindicating the

rights of the class and in furthering the public policy of the

nation of eliminating racial discrimination in the public schools

Cf. Newman v. piggie park Enterprises, Inc., supra.

This appeal would not have been required had the

district complied as directed by the district court on August

29, 1968. Neither the appeal nor the trial below should have

been necessary at all. The mandate of Brown and Green is all

too clear. Negro citizens should not be forced to resort to

the courts for protection, bearing the "constant and crushing

-23-

expense of enforcing their constitutionally accorded rights."

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F.2d 661, 671 (8th

Cir. 1966).

As early as Brown II and most recently in Green,

the Supreme Court reiterated that the burden is on the state

and indirectly the local boards to initiate, develop and

implement plans disestablishing prior state-imposed segregation.

In this case a dual school system has been maintained for some

15 years in flagrant violation of the Constitution. It should

not have been necessary for Negro plaintiffs to bring legal

action to obtain its dissolution. That burden should have been

assumed by the State through its agent, the School Board. Only

the award of substantial counsel fees, based upon the substantial

like sums expended from public funds in the attempt to preserve

the dual system, will prod unwilling state officials to assume,

at long last, their constitutional obligations by initiating,

without awaiting suit by Negroes, the requisite transitions to

unitary nonracial systems.

The time has come for this Court to make it clear to

recalcitrant school boards that their constitutional obligations

do not depend in each and every instance on specific orders

from the courts. The history of school desegregation in this

Circuit is a painful one. Again and again this Court has been

required to consider cases, such as this one, where the law and

the facts are perfectly clear but where the school board simply

will not budge without a court order. This situation is no

longer tolerable. it puts the burden of expensive litigation

-24-

on the Negro schoolchildren and their lawyers. The rights of

the schoolchildren are not vindicated unless attorneys or legal

service organizations are available to serve without fee and

subsidize the expenses of l i t i g a t i o n / There will inevitably

be many cases where there are no attorneys in a position to

exercise the diligence essential to protecting the rights of

the children. The only just solution is to impose the expense

of unnecessary desegregation litigation on the party causing the

expense — the recalcitrant school board — and to reward the

"private attorney general" (Newman, supra, 393 U.S. at 402) for

28/ Civil rights cases ordinarily do not generate legal fees,

contingent or otherwise. See generally, on problems of

representation in civil rights cases, Sanders v. Russell, 401

F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968). As to representation by legal service

organizations, Senator Hart made the following comments on the

counsel fees provision of the Fair Housing Act of 1968:

Frequently indigent plaintiffs are

represented by legal associations, acting

as "private attorneys general" in the

vindication of important constitutional

and statutorily created rights. it would

be most anomalous if courts were per

mitted to deny these costs, fees, and

damages to an obviously indigent plain

tiff, simply because he was represented

by a legal association. I think it

should be clearly understood that this

representation in no way limits a

plaintiff's right of recovery.

114 Cong. Rec. S2308 (daily ed., March 6, 1968).

See also, Sanders v. Russell, supra, at 244 n.5.

-25-

performing the public function of eradicating unconstitutional

discrimination in the public schools. This would also serve

the salutary purposes of inducing the school board to live up

to its clear obligations and of removing unnecessary litigation

from the courts. What is needed here is an added sanction

imposed against unnecessary litigation occasioned by clearly

unconstitutional conduct. What is needed is an effective deter—

to the recalcitrance and obstinate refusal to recognize that

court decrees mean what they say revealed by this record. We

believe that the imposition of attorneys' fees will go a long way

toward meeting those needs.

Finally, for the same reasons, this Court should award

counsel fees on the appeal. Cf. Gilbert v. Hoising & Portable

Engineers, 23[7 Ore. 139, 390 P.2d 320 (1964) ; Coppedge v. Franklin

County Bd. of Educ., 404 F.2d 1177 (4th Cir. 1968); but see,

Felder v. Harnett County Bd. of Educ., No. 12,894 (4th Cir.,

April 22, 1969).

29/ Awarding counsel fees to encourage "public" litigation by

private parties is an accepted device. For example, in Oregon,

union members who succeed in suing union officers guilty of wrong

doing are entitled to counsel fees both at the trial level and on

appeal, because they are protecting an interest of the general public

If those who wish to preserve the internal demo

cracy of the union are required to pay out of their own pockets the cost of employing counsel, they are

not apt to take legal action to correct the abuse.

. . . The allowance of attorneys' fees both in the

trial court and on appeal will tend to encourage

union members to bring into court their complaints

of union mis-management and thus the public interest

as well as the interest of the union will be served.

Gilbert v. Hoidinq & Portable Engineers, 237 Ore. 139, 390 P.2d

320 (1964) . See also Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R R . 186 F 2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951). ' --

-26-

CONCLUSION

For all of the above reasons, the order and judgment

of the district court should be reversed, and the cause remanded

with instructions to require thfe implementation at the earliest

possible moment of the desegregation plan proposed by appellants'

expert witness at the August 6, 1968 hearing of this cause, and

substantial attorneys' fees should be awarded to appellants as

part of their costs in this Court; the district court should be

further instructed to award plaintiffs-appellants reasonable

attorneys' fees. Appellants further pray that this Court award

them their costs, and for such other relief as to this Court may

appear appropriate and just.

Respectfully submitted

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

BURL C. ROTENBERRY

1820 W. 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

GEORGE HOWARD, JR.

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 71601

Attorneys for Appellants

-27-