Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

June 24, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner, 1988. 2771d3d0-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7268dac9-59ce-42cc-9b9b-2a58c07db68c/patterson-v-mclean-credit-union-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

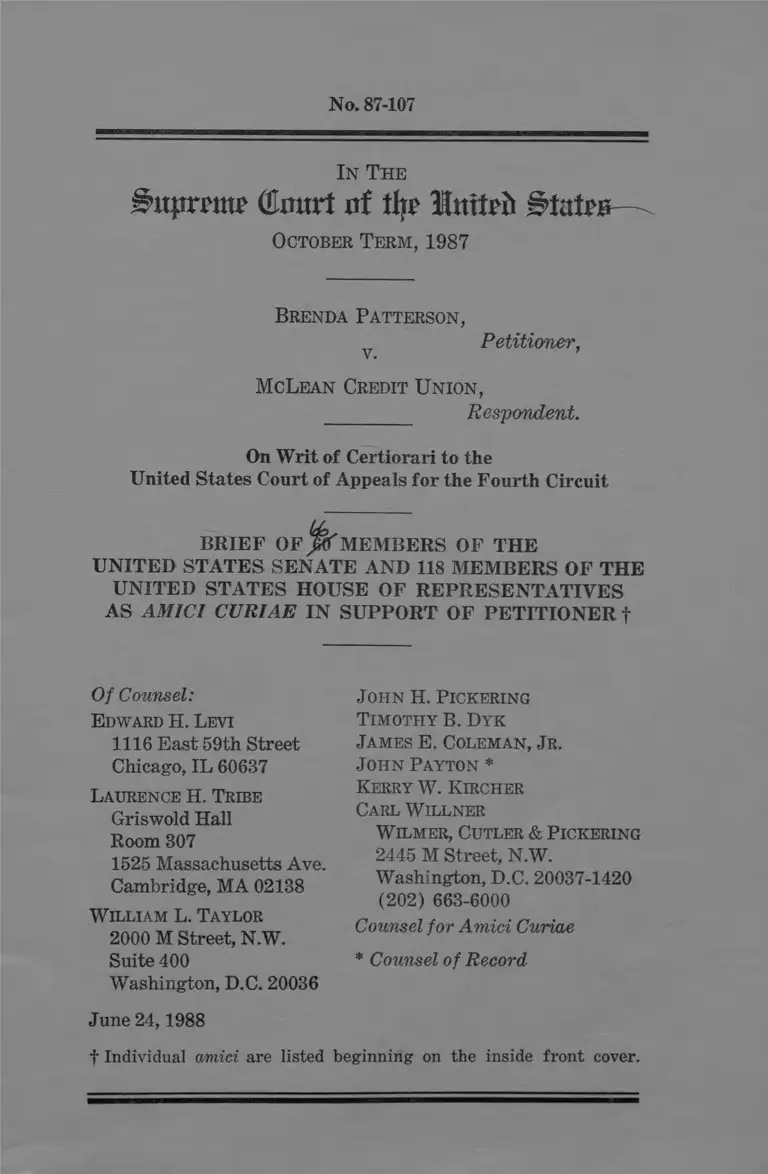

No. 87-107

In T he

(Emtrt uf tfyp United i>tatpa—

October Term , 1987

Brenda Patterson,

y Petitioner,

McLean Credit Union,

_________ Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF MEMBERS OF THE

UNITED STATES SENATE AND 118 MEMBERS OF THE

UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER f

Of Counsel:

Edward H. Levi

1116 East 59th Street

Chicago, IL 60637

L aurence H. Tribe

Griswold Hall

Room 307

1525 Massachusetts Ave.

Cambridge, MA 02138

W illiam L. Taylor

2000 M Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

June 24,1988

John H. P ickering

T im oth y B. Dyk

Jam es E. Colem an , Jr .

John P ayton *

K erry W. K ircher

Carl W illner

W ilmer, Cutler & P ickering

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037-1420

(202) 663-6000

Counsel for Amici Curiae

* Counsel of Record

f Individual amici are listed beginning on the inside front cover.

MEMBERS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE

Edward M. Kennedy, Alien Specter, Robert C. Byrd, Bill

Bradley, Alan Cranston, Daniel J. Evans, Ernest F. Hollings,

J. Bennett Johnston, Patrick J. Leahy, Howard M. Metzen-

baum, Barbara A. Mikulski, George J. Mitchell, Bob Pack-

wood, Paul Simon, Robert T. Stafford, Lowell P. Weicker, Jr.,

Brock Adams, Max Baucus, Lloyd Bentsen, Christopher Bond,

David L. Boren, Rudy Boschwitz, Dale Bumpers, Quentin N.

Burdick, John H. Chafee, Lawton Chiles, William S. Cohen,

Kent Conrad, AlfonseM. D’Amato, John C. Danforth, Thomas

Andrew Daschle, Dennis DeConcini, Alan J. Dixon, Christo

pher J. Dodd, David Durenberger, Wyche Fowler, Jr., John

Glenn, Albert Gore, Jr., Bob Graham, Tom Harkin, Mark

O. Hatfield, John Heinz, Daniel K. Inouye, John F. Kerry,

Frank R. Lautenberg, Carl Levin, Spark M. Matsunaga, John

Melcher, Daniel P. Moynihan, Sam Nunn, Claiborne Pell,

William Proxmire, David Pryor, Harry Reid, Donald W.

Riegle, Jr., John D. Rockefeller, IV, Terry Sanford, Paul S.

Sarbanes, Jim Sasser, Timothy E. Wirth

Don Edwards, Hamilton Fish, Jr., Augustus F. Hawkins,

James M. Jeffords, Patricia Schroeder, Tony Coelho, Peter

W. Rodino, Jr., Gary L. Ackerman, Daniel K. Akaka, Glenn

M. Anderson, Chester G. Atkins, Les AuCoin, Howard L.

Berman, Don Bonker, Robert A. Borski, Rick Boucher,

Barbara Boxer, Jack Brooks, George E. Brown, Jr., John

W . Bryant, Albert G. Bustamante, Benjamine L. Cardin,

Thomas Richard Carper, William L. Clay, Ronald D. Coleman,

Cardiss Collins, John Conyers, Jr., George W. Crockett, Jr.,

Ronald V. Dellums, Julian C. Dixon, Thomas J. Downey,

Mervyn M. Dymally, Mike Espy, Lane A. Evans, Dante B.

Fascell, Walter E. Fauntroy, Vic Fazio, Edward F. Feighan,

Floyd H. Flake, James J. Florio, Thomas M. Foglietta, Harold

E. Ford, William D. Ford, Barney Frank, Martin Frost,

Robert Garcia, Samuel Gejdenson, Richard A. Gephardt,

Benjamin A. Gilman, Dan Glickman, Kenneth J. Gray, Wil

liam H. Gray, III, Charles A. Hayes, George J. Hochbrueckner,

Steny H. Hoyer, Robert W. Kastenmeier, Joseph P. Kennedy,

II, Gerald D. Kleczka, Tom Lantos, Richard H. Lehman,

William Lehman, Mickey Leland, Sander M. Levin, Mel

Levine, John Lewis, Mike Lowry, Thomas A. Luken, Matthew

F. McHugh, Thomas J. Manton, Edward J. Markey, Mat

thew G. Martinez, Robert T. Matsui, Nicholas Mavroules,

Romano L. Mazzoli, Kweisi Mfume, George Miller, Norman

Y. Mineta, Jim Moody, Constance A. Morelia, Bruce A. Mor

rison, Austin J. Murphy, Stephen L. Neal, Solomon P. Ortiz,

Major R. Owens, Leon E. Panetta, Nancy Pelosi, Carl C.

Perkins, David E. Price, Charles B. Rangel, Bill Richardson,

Tommy F. Robinson, Robert A. Roe, Edward R. Roybal,

Martin Olav Sabo, Gus Savage, Thomas C. Sawyer, James

H. Scheuer, Claudine Schneider, Charles E. Schumer, Gerry

Sikorski, Jim Slattery, Louise M. Slaughter, Lawrence J.

Smith, Harley O. Staggers, Jr., Fortney H. Stark, Louis

Stokes, Mike Synar, Esteban Edward Torres, Robert G. Tor

ricelli, Edolphus Towns, Bob Traxler, Morris K. Udall, Bruce

F. Vento, Doug Walgren, Henry A. Waxman, Alan Wheat,

Charles Wilson, Robert E. Wise

MEMBERS OF THE UNITED STATES

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................................. iii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ....................................... 1

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT________ 2

ARGUMENT........................................................................ 4

I. SECTION 1981, AS INTERPRETED BY THIS

COURT, IS AN INTEGRAL COMPONENT OF

THIS NATION’S CIVIL RIGHTS LAWS - ..... 5

II. STARE DECISIS DICTATES CONTINUED

ADHERENCE TO THE INTERPRETATION

OF SECTION 1981 ADOPTED BY THIS

COURT IN RUNYON v. McCRARY............... 7

A. The Institutional Relationship Between the

Congress and the Court Makes Application of

Stare Decisis to a Statutory Interpretation

Such As Runyon v. McCrary Particularly

Appropriate........................................................ 10

B. There Are No Special Circumstances in This

Case That Justify Overruling Runyon v. Mc

Crary .................................................................. 12

1. The Interpretation of Section 1981

Adopted in Runyon v. McCrary Was Not

Based Upon an Incomplete Analysis....... 12

2. The Interpretation of Section 1981

Adopted in Runyon v. McCrary Has Not

Been Undercut by Subsequent Legal De

velopments ................................................... 14

3. The Interpretation of Section 1981

Adopted in Runyon v. McCrary Has Not

Proved Confusing or Unworkable in Prac

tice ................................................................ 16

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

11

4. Overruling the Interpretation of Section

1981 Adopted in Runyon v. McCrary

Would Frustrate Legitimate Reliance In

terests ............................................................ 17

5. There Has Been No Relevant Change in

Social, Economic or Other Factual Cir

cumstances Since Runyon v. McCrary....... 19

III. STARE DECISIS APPLIES WITH SPECIAL

FORCE BECAUSE THE CONGRESS HAS AF

FIRMATIVELY ENDORSED THIS COURT’S

INTERPRETATION OF SECTION 1981.......... 20

CONCLUSION .................................................................... 29

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society,

421 U.S. 240 (1975) ............................................... 26

Andrews v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co.,

406 U.S. 320 (1972) ................................................ 15

Arizona v. Rumsey, 467 U.S. 203 (1984)........ ........ 12

Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S.

574 (1983) .................. _..........................................2,15,19

Boys Markets, Inc. v. Retail Clerks Union, Local

770, 398 U.S. 235 (1970) ........... ......................10,11,15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).. 19

Brown v. Dade Christian Schools, Inc., 556 F.2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1063

(1978) ...... ....... ................ ...................................... 17

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677

(1979) ...................................................................... 22

City of Memphis v. Greene, 451 U.S. 100 (1981).— 15

Commissioner v. Fink, 107 S. Ct. 2729 (1987)........ 11

Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433

U.S. 36 (1977) ........................................................ 10

Cook v. Hudson, 429 U.S. 165 (1976)...................... 15

Copperweld Corp. v. Independence Tube Corp., 467

U.S. 752 (1984)...................................................... 12

Douglas v. Seacoast Products, Inc., 431 U.S. 265

(1977) ...................................................................... 21

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974)....... ........ 10

Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64

(1938) ...................................................................... 10

Ex Parte Bollman, 8 U.S. (4 Cranch) 75 (1807).... 8

Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1972) ....................... 21

Florida Department of Health v. Florida Nursing

Home Association, 450 U.S. 147 (1981) ....... ..... 8, 9

Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Au

thority, 469 U.S. 528 (1985) ......... 16

General Building Contractors Association v. Penn

sylvania, 458 U.S. 375 (1982).............................. 14,15

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 107 S. Ct. 2617

(1987) ...................................................................... 15

Great American Federal Savings & Loan Associa

tion v. Novotny, 442 U.S. 366 (1979) ................. 15

iii

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Grove City College v. Bell, 465 U.S. 555 (1984) .... 6,10

Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway Co. v. Moser,

275 U.S. 133 (1927) ................................................ 11

Gulf stream Aerospace Corp. v. Mayacamas Corp.,

108 S. Ct. 1133 (1988) ............................................ 16

Hall v. Pennsylvania State Police, 570 F.2d 86 (3d

Cir. 1978) ................................................................ 17

Hecht v. Malley, 265 U.S. 144 (1924) ...................... 21

Helvering v. Hallock, 309 U.S. 106 (1940)............. 8

Herman & MacLean v. Huddleston, 459 U.S. 375

(1983) ...................................................................... 22

Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984) ..... 15

Hollander v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 450 F. Supp.

496 (D. Conn. 1978) ....... ....................................... 17

Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U.S. 720 (1977).... 10

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S.

454 (1975) ....... passim

Joint Industry Board v. United States, 391 U.S.

224 (1968) ................................................................ 21

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409

(1968) ........................ passim

Lindahl v. OPM, 470 U.S. 768 (1985).................... 22,23

Local 28 of the Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC, 106

S. Ct. 3019 (1986) .......... 21

Manzanares v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 593 F.2d 968

(10th Cir. 1979) ......... 17

McDonald v. Sante Fe Trail Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976) ................................................ 15

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. v. Cur

ran, 456 U.S. 353 (1982) ....................................... 22, 28

Miller v. Hall’s Birmingham Wholesale Florist, 640

F. Supp. 948 (N.D. Ala. 1986) ........................ 17

Missouri v. Ross, 299 U.S. 72 (1936) ..................... 22

Mitchell v. W. T. Grant Co., 416 U.S. 600 (1974).... 19

Monell v. Department of Social Services, 436 U.S.

658 (1978) .................................................................... passim

Monessen Southwestern Railway Co. v. Morgan, 56

U.S.L.W. 4494 (June 6, 1988).......

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961)

22

15,17

V

Moragne v. State Marine Lines, Inc., 398 U.S. 375

(1970) .................... 9

Moye v. Chrysler Corp., 465 F. Supp. 1189 (E.D.

Mo.), aff’d, 615 F.2d 1365 (8th Cir. 1979)......... 17

NLRB v. International Longshoremen’s Associa

tion, 473 U.S. 61 (1985) ............................................ 10

National League of Cities v. Usery, 426 U.S. 833

(1976) .............................................................................. 16

Nieto v. UAW, Local 598, 672 F. Supp. 987 (E.D.

Mich. 1987) ..................................................................... 17

Patsy v. Board of Regents, 457 U.S. 496 (1982)..18, 21, 22

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).............. 19

Puerto Rico v. Branstad, 107 S. Ct. 2802 (1987)..... 15

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976).................. passim

Saint Francis College v. Al-Khazraji, 107 S. Ct.

2022 (1987) ...... 15

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91 (1945) .......... 20

Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb, 107 S. Ct. 2019

(1987) ............................................................................. 13

Shapiro v. United States, 335 U.S. 1 (1 94 8 )...... ...... 21

Square D. Co. v. Niagara Frontier Tariff Bureau,

Inc., 476 U.S. 409 (1986) ............ ........................... 10,22

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229

(1969) ......... ............... ................. -.................................. 13

Swift & Co. v. Wickham, 382 U.S. I l l (1965)........ 16

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975) ................ 19

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Association,

Inc., 410 U.S. 431 (1 97 3 ).......................................... 13

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299 (1941)......... 20

United States v. Embassy Restaurant, Inc., 359

U.S. 29 (1959) ............... ......................-........................ 21

Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U.S. 254 (1986).................... 9,12

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970) ................... 8

Wright v. Salisbury Club, Ltd., 632 F.2d 309 (4th

Cir. 1980)....................................................................... 17

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

VI

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, 42 U.S.C

§§ 2000e et seq. (1982)..........................-.......~~4, 5, 23

Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976,

Pub. L. No. 94-559, 90 Stat. 2641 (1976) ............ 4, 26

Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, Pub. L. No.

100-259, 102 Stat. 28 (1988)...................... -.......- 6,7

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub.

L. No. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103 (1972)......................- 23

Equal Pay Act of 1963, 29 U.S.C. § 206(d) (1982).. 23

42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1982) .............................................. passim

42 U.S.C. § 1982 (1982) ............................................ .passim

42 U.S.C. § 1983 (1982).... ..........................-.........----- 17

42 U.S.C. § 1988 (1982) ________ - .......- - ................. 26

Legislative Materials:

117 Cong. Rec. 31973 (1971).................... ................ 25

117 Cong. Rec. 31978 (1971)......................-............ 25

117 Cong. Rec. 31979 (1971)................................... 25

117 Cong. Rec. 32100 (1971).................................... 25

117 Cong. Rec. 32111 (1971).................... 25

118 Cong. Rec. 3173 (1972) .......................-............. 23

118 Cong. Rec. 3370 (1972)...... ..............................- 23

118 Cong. Rec. 3371 (1972) ....................................... 23, 24

118 Cong. Rec. 3372 (1972) ..................................... 24

118 Cong. Rec. 3373 (1972) ............. - ...........----- 24

121 Cong. Rec. 26806 (1975).................................... 28

130 Cong. Rec. 3661 (1984)...................................... 6

130 Cong. Rec. S4585 (daily ed. Apr. 12, 1984) ..... 6

131 Cong. Rec. 901 (1985)........................ ..............- 6

131 Cong. Rec. 2149 (1985)................................ -..... 6

131 Cong. Rec. 2151 (1985) ...........................-........... 6

133 Cong. Rec. S2249 (daily ed. Feb. 19,1987) ....... 7

134 Cong. Rec. S266 (daily ed. Jan. 28, 1988)..... 7

134 Cong. Rec. H597 (daily ed. Mar. 2, 1988)....... 7

134 Cong. Rec. H1071 (daily ed. Mar. 22, 1988)... 7

134 Cong. Rec. S2744 (daily ed. Mar. 22, 1988) .... 6

134 Cong. Rec. S2751 (daily ed. Mar. 22,1988)____ 7

134 Cong. Rec. S2765 (daily ed. Mar. 22, 1988).... 7

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 899, 92d Cong., 2d Sess.

(1972) ...................................................................... 25

H.R. Rep. No. 238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ..... 25, 27

Statutes: Page

Page

H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976) 26, 27

H.R. Rep. No. 963, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. (1986) 7

S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976)...... 28

S. Rep. No. 64, 100th Cong., 2d Sess. (1988) ......... 6, 7

Other Authorities:

Brief for the Secretary of Commerce, Fullilove v.

Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980) (No. 78-1007).. 16

Brief for the United States, Goldsboro Christian

Schools, Inc. v. United States, reported as Bob

Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574

(1983) (No. 81-1)................................................... 15

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae,

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976) (No. 75-260)........................ 16

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae,

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) (No.

75-62) ....................................................................... 14,16

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Supporting Petitioner, Patterson v. McLean

Credit Union (No. 87-107) ................................. 15

B. Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process

(1921) ....................................................................... 8

K. Llewellyn, The Bramble Bush (1951) ............... 8

Message to the Senate on Civil Rights Legislation,

24 Weekly Comp. Pres. Doc. 353 (Mar. 16,

1988) ......................................................................... 7

Monaghan, Stare Decisis and Constitutional Ad

judication, 88 Colum. L. Rev. 723 (1988)............. 9

R. Wasserstrom, The Judicial Decision: Toward a

Theory of Legal Justification (1961) ................... 8

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

In T he

(Emtrt of tip Itttfrft BUiUb

October Term, 1987

No. 87-107

Brenda Patterson,

Petitioner,

McLean Credit Union,

_________ Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF JKT MEMBERS OF THE

UNITED STATES SENATE AND 118 MEMBERS OF THE

UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE1

u Amici curiae are a bipartisan congressional group of

M members of the United States Senate and 118 members

of the United States House of Representatives.2 Amid

have a dual interest in this Court’s reconsideration of the

interpretation of Section 1981, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, adopted

in Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976). First,

amici have an institutional interest in the stability of

statutory precedents. That concern is particularly com

pelling here because this Court is calling into question

1 Both petitioner and respondent have consented to the filing of

this brief. Letters of consent are on file with the Clerk of the

Court.

2 Individual amici are listed beginning on the inside front cover.

2

the validity of its interpretation of Section 1981, long

after the Congress has accepted that interpretation and

acted affirmatively to build upon it.

Second, amici have a significant interest here because

of their role in enacting legislation to eradicate the evils

of racial discrimination. Such discrimination, as this

Court has recognized, is contrary to “ fundamental public

policy,” 8 and its elimination has become, particularly

over the past three decades, a paramount national goal.

Section 1981, as interpreted by this Court, furthers that

policy. It covers a range of conduct that other statutes

do not reach, such as the racial discrimination in private

school admissions at issue in Runyon.

The interests of amici would be adversely affected by

the overruling of Runyon. The legislative effort neces

sary to restore this Court’s original interpretation would

likely be fractious and divisive, since corrective legisla

tion would, in all likelihood, compel the Congress to ad

dress numerous peripheral questions concerning the scope

and application of Section 1981.

For these institutional reasons, amici urge this Court

not to overturn Runyon’s interpretation of Section 1981

as prohibiting intentional racial discrimination in the

making and enforcing of private contracts. Amici take

no position on whether Section 1981 should apply to the

particular facts of this case.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

This Court’s interpretation of Section 1981 in Runyon

v. McCrary as prohibiting private discrimination in the

making and enforcing of contracts should not be over

turned. Section 1981, as interpreted in Runyon, is an

essential component of the statutory framework barring

discrimination by private parties. It affords a broad-

based remedy for intentional racial discrimination that

8 Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 461 U.S. 574, 594 (1983).

3

complements other more specific statutes. Overturning

Runyon and forcing the Congress to revisit this area

would not only impose significant, unnecessary burdens

on the legislative process, but could threaten the repose

that the Nation has obtained on the issue of racial dis

crimination. Adherence to stare decisis is essential if the

unique interplay between the Congress and the Court

that has existed in the development of civil rights law is

to be maintained.

The Congress’ primary role in lawmaking under the

Constitution dictates that any change in the meaning

of a statute be effected legislatively rather than ju-

dically. In exercising its constitutional power to leg

islate, the Congress must be able to rely on the sta

bility of the Court’s interpretations of its statutes. For

this reason, stare decisis, as this Court has repeatedly

recognized, operates with its greatest strength where a

statutory interpretation, such as Runyon, is concerned.

There are no special circumstances present here that

would justify departing from stare decisis and this cus

tomary institutional relationship between the Congress

and the Court. First, Runyon was not based on an in

complete analysis. Rather, it was the culmination of a

series of decisions in which the Court thoroughly analyzed

the legislative history of Section 1981 and considered the

arguments for and against the applicability of Section

1981 to private conduct. Second, Runyon was not a sport

in the law, nor have subsequent legal developments un

dercut its vitality. Instead, Runyon has been accepted as

well-settled law by this Court, by the Executive, and by

the Congress. Third, Runyon’s interpretation of Section

1981 is a straightforward rule which has been readily

applied by the lower courts and has not proven confusing

or unworkable. Fourth, individuals have legitimately re

lied upon Section 1981’s prohibition of private contract-

related discrimination since Runyon, and that reliance

would be frustrated were Runyon to be overturned.

Fifth, and finally, no relevant factual circumstances,

4

whether social, economic or otherwise, have changed since

Runyon was decided.

The case against overturning Runyon is particularly

strong because the Congress has affirmatively endorsed

this Court’s construction of Section 1981 as reaching

private discrimination. The Court has found congres

sional approval of a judicial construction of a statute in

cases where the Congress has (1) rejected efforts to pass

legislation that would have overruled or limited the reach

of the judicial interpretation, or (2) failed to change the

judicial interpretation in the course of enacting or

amending related legislation which reflects the Congress’

awareness of that interpretation. Both these circum

stances are present here.

At two key junctures, the Congress has made its intent

plain. In 1972, when considering amendments to Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Congress ad

dressed and rejected proposals to eliminate recourse to

Section 1981 in the area of employment discrimination.

In 1976, the Congress enacted the Civil Rights Attorney’s

Fees Awards Act, which extended to prevailing parties

the right to recover attorney’s fees in actions brought

under Section 1981. The Congress recognized, in consid

ering this legislation, that Section 1981 provides reme

dies for discrimination by private parties. These actions,

explicitly predicated on Section 1981 continuing to have

the meaning given to it by this Court, give rise to a

virtually conclusive presumption that the Congress has

approved Runyon.

ARGUMENT

In Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976), this

Court held that Section 1981 prohibits racial discrimina

tion in the making and enforcement of private contracts.

The Court has now requested the parties to brief

“ [wjhether or not th [at] interpretation . . . should be

reconsidered.” Amici urge the Court not to overrule

Runyon.

5

I. SECTION 1981, AS INTERPRETED BY THIS

COURT, IS AN INTEGRAL COMPONENT OF THIS

NATION’S CIVIL RIGHTS LAWS.

Runyon is one of the essential civil rights precedents

established by this Court over the past twenty years. In

1968, the Court foreshadowed Runyon by holding in

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), that

Section 1982, 42 U.S.C. § 1982, a related statute, pro

hibits racial discrimination in private property transac

tions. Then, in 1975, the Court concluded in Johnson v.

Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454 (1975),

that Section 1981 reaches private discrimination in em

ployment. Runyon simply built upon these foundations.

As interpreted in Runyon, Section 1981 is an integral

component of the statutory framework that the Congress

has developed to bar private racial discrimination. Other

more detailed statutes afford comprehensive remedies for

acts of discrimination by specified private parties, e.g.,

employers of a certain size, restaurants, and hotels. These

statutes often have easier standards of proof and are

often enforceable by the Executive Branch.4 Section 1981

affords victims of discrimination a complementary, broad-

based remedy for many forms of contract-related inten

tional racial discrimination, including discrimination by

parties not covered by other statutes. It is not an exag

geration to say that overturning Runyon, and adopting

the view that Section 1981 addresses only state statutes

and other state actions that disable minorities from mak

ing or enforcing contracts, would effectively render Sec

tion 1981 a nullity. Under that reading, Section 1981

would bar only conduct that is already prohibited by the

Fourteenth Amendment by its own force.

Amici’s concern for the viability of Runyon’s interpre

tation of Section 1981 is not lessened by the fact that the

Congress may legislatively alter a statutory interpreta

4 See, e.g., Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e

et seq.

6

tion of the Court. Any congressional effort to change a

decision of this Court could prove divisive and time con

suming, could well be delayed by disagreement over col

lateral issues, and could confront grave difficulties in ad

dressing the nuances that have arisen from case-by-case

elaboration of the statute. But with regard to one of the

core civil rights statutes, the costs are far greater. To

require the Congress to revisit this issue could jeopardize

the closure and repose that we have obtained as a Nation

on the issue of racial discrimination. If the Court over

turns Runyon, intentional racial discrimination that is

now illegal could exist for years without remedy, while

the Congress debates the scope and details of new legis

lation.

The experience with this Court’s decision in Grove

City College v. Bell, 465 U.S. 555 (1984), is illustra

tive. The Court concluded in 1984 that the Congress

had intended that statutory provisions prohibiting dis

crimination in certain federally-funded programs be

narrowly construed. Despite overwhelming agreement

that Grove City should be overturned, it took the Con

gress a “ long and troubled” 0 four years— in significant

part because of disagreements over collateral issues— to

enact legislation to accomplish that result.'8 In the mean- * 6

® 134 Cong. Rec. S2744 (daily ed. Mar. 22, 1988) (statement of

Sen. Chafee).

6 See Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, Pub. L. No. 100-259,

102 Stat. 28 (1988). One bill to overturn this Court’s decision in

Grove City was introduced the same day the decision was handed

down. 130 Cong. Rec. 3661-62 (1984). Another bill, introduced

two months later, 130 Cong. Rec. S4585 (daily ed. Apr. 12, 1984),

actually passed in the House of Representatives, but failed in the

Senate due to an end-of-session filibuster. 131 Cong. Rec. 2149

(1985) (statement of Sen. Kennedy) ; S. Rep. No. 64, 100th Cong.,

2d Sess. 3 (1988). In the next session of the Congress, legislation

to overturn Grove City was introduced in both the House and Sen

ate. 131 Cong. Rec. 901 (1985) (House) ; 131 Cong. Rec. 2151

(1985) (Senate). The Senate bill was never reported out of the

7

time, institutions receiving federal funds were free to

discriminate on racial or other grounds as long as they

did not discriminate in particular federally-funded pro

grams.7

Amici wish to make clear that what is at stake here

is not legislative convenience, but the vital interaction

that has developed between the Congress and the Court

in protecting the Nation against the evils of racial dis

crimination. The doctrine of stare decisis is essential to

that interaction.

II. STARE DECISIS DICTATES CONTINUED ADHER

ENCE TO THE INTERPRETATION OF SECTION

1981 ADOPTED BY THIS COURT IN RUNYON v.

McCRARY.

The orderly functioning of our government requires

that the Congress be able to rely on the stability of stat

Committee on Labor and Human Resources. S. Rep. No. 64, 100th

Cong., 2d Sess. 3 (1988). In the House, the bill was favorably

reported by both the Judiciary and the Education and Labor Com

mittees, H.R. Rep. No. 963, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. Parts 1 and 2

(1986), but was never brought to the full House.

The Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 was introduced on

February 19, 1987, with 51 senators cosponsoring the bill. 133

Cong. Rec. S2249 (daily ed. Feb. 19, 1987). But it was not until

almost a year later that it passed in the Senate, 134 Cong. Rec.

S266 (daily ed. Jan. 28, 1988), and several weeks more before it

passed in the House. 134 Cong. Rec. H597-98 (daily ed. Mar. 2,

1988). The President vetoed the bill, principally because of con

cerns that it might impinge upon the affairs of religious institu

tions and small businesses. Message to the Senate on Civil Rights

Legislation, 24 Weekly Comp. Pres. Doc. 353 (Mar. 16, 1988).

The Congress overrode the veto and thus, more than four years

after Grove City was decided, overturned that decision. 134 Cong.

Rec. S2765 (daily ed. Mar. 22, 1988) (Senate override) ; 134 Cong.

Rec. H1071-72 (daily ed. Mar. 22, 1988) (House override).

7 See 134 Cong. Rec. S2751 (daily ed. Mar. 22, 1988) (statement

of Sen. Domenici) ( “ [F ]or the past 4 years, while legislation has

been drafted and redrafted and hearings have been held, dis

crimination against individuals on the basis of race, sex, age, and

physical handicap has occurred because of the Supreme Court’s

decision.” ).

8

utory interpretations. Once the Congress has enacted a

law, and this Court has interpreted it, the Congress re

lies on the Court to refine that precedent and apply it to

specific cases. But the Congress must be able to assume

that a construction of a statute, rendered by this Court

after full and fair consideration, is fixed so that the

Congress can build upon it if it chooses. Without the ex

ceptional vigor of stare decisis in the statutory arena,

this partnership between the Congress and the Court

would break down. If that happened, the Congress would

bear a continuing and onerous burden of having to signal

its agreement with each of the Court’s statutory inter

pretations, or face unexpected reversal of those interpre

tations.

The doctrine of stare decisis is a venerable principle

of judicial decisionmaking which has been recognized by

this Court since the earliest days of the Republic.6 * 8 It has

retained its importance because of the fundamental values

it protects and promotes. First, it furthers “ the stability

and predictability required for the ordering of human

affairs over the course of time.” 9 Second, it promotes

judicial efficiency by ensuring that today’s judges need

not rehear every past decision, but can instead “ lay

[their] own course of bricks on the secure foundation of

the courses laid by others who [have] gone before

[them].” 10 Finally, in the broadest and grandest sense,

6 See, e.g., Ex parte Bolivian, 8 U.S. (4 Cranch) 75, 100 (1807).

9 Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78, 127 (1970) (Harlan, J., con

curring in part and dissenting in part). See also Helvering v. Hal-

lock, 309 U.S. 106, 119 (1940) ( “ [S~\tare decisis embodies an im

portant social policy. It represents an element of continuity in

law, and is rooted in the psychologic need to satisfy reasonable

expectations.” ).

10 B. Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process 149 (1921).

See also Florida Dep’t of Health v. Florida Nursing Home Ass’n,

450 U.S. 147, 154 (1981) (Stevens, J., concurring) ; R. Wasser-

strom, The Judicial Decision: Toward a Theory of Legal Justifica

tion 72-73 (1961); K. Llewellyn, The Bramble Bush 64-65 (1951).

9

it legitimates our system of the rule of law, and the role

of the Supreme Court in that system.11 Justice Harlan

summed up these considerations for a unanimous Court

18 years ago:

Very weighty considerations underlie the principle

that courts should not lightly overrule past decisions.

Among these are the desirability that the law furnish

a clear guide for the conduct of individuals, to enable

them to plan their affairs with assurance against

untoward surprise; the importance of furthering fair

and expeditious adjudication by eliminating the need

to relitigate every relevant proposition in every case;

and the necessity of maintaining public faith in the

judiciary as a source of impersonal and reasoned

judgments.12

Thus, in reconsidering any established rule, this Court

must give great weight to these considerations. In this

case their proper application is clear. Runyon should not

be overruled.

11 See, e.g., Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U.S. 254, 265-66 (1986)

(Stare decisis “permits society to presume that bedrock principles

are founded in the law rather than in the proclivities of individ

uals, and thereby contributes to the integrity of our constitutional

system of government, both in appearance and in fact.” ) ; Florida

Dep’t of Health v. Florida Nursing Home Ass’n, 450 U.S. at 154

(Stevens, J., concurring) ( “ Citizens must have confidence that

the rules on which they rely in ordering their affairs . . . are

rules of law and not merely the opinions of a small group of men

who temporarily occupy high office.” ) ; Monaghan, Stare Decisis

and Constitutional Adjudication, 88 Colum. L. Rev. 723, 749, 752

(1988) ( “ [SJtare decisis operates to promote system-wide stability

and continuity by ensuring the survival of governmental norms

that have achieved unsurpassed importance in American society.

. . . A general judicial adherence to constitutional precedent sup

ports a consensus about the rule of law, specifically the belief that

all organs of government, including the Court, are bound by the

law.” ). ' :W -

12 Moragne v. State Marine Lines, Inc., 398 U.S. 375, 403 (1970).

10

A. The Institutional Relationship Between the Con

gress and the Court Makes Application of Stare

Decisis to a Statutory Interpretation Such As

Runyon v. McCrary Particularly Appropriate.

Runyon is a statutory rather than a constitutional

holding. This Court has repeatedly distinguished between

constitutional and statutory cases for purposes of stare

decisis, and has pronounced itself particularly loath to

ignore the doctrine of stare decisis where an earlier stat

utory interpretation is at issue, given that “ stare decisis

has more force in statutory analysis than in constitu

tional adjudication . . . .” 18 The Court has adhered to

that axiom in practice.

One reason for this distinction is that “ in the area of

statutory construction . . . Congress is free to change

this Court’s interpretation of its legislation.” 13 14 Another

13 Monell v. Department of Social Serv., 436 U.S. 658, 695

(1978). See also id. at 708 (Powell, J., concurring); id. at

714 (Rehnquist, J., dissenting) ( “ [C]onsiderations of stare decisis

are at their strongest when this Court confronts its previous

constructions of legislation.” ) ; Square D Co. v. Niagara Fron

tier Tariff Bureau, Inc., 476 U.S. 409, 424 (1986) (A “ strong

presumption of continued validity . . . adheres in the judicial in

terpretation of a statute.” ) ; NLRB v. International Longshore

men’s Ass’n, 473 U.S. 61, 84 (1985) ( “ [W ]e should follow the nor

mal presumption of stare decisis in cases of statutory interpreta

tion.” ) ; Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433 U.S. 36,

60 (1977) (White, J., concurring) ( “ [CJonsiderations of stare

decisis are to be given particularly strong weight in the area of

statutory construction.” ) ; Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U.S.

720, 736 (1977) ( “ [CJonsiderations of stare decisis weigh heavily

in the area of statutory construction. . . .” ) ; Runyon v. McCrary,

427 U.S. at 175; Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 671 n.14 (1974) ;

Boys Markets, Inc. v. Retail Clerks Union, Local 770, 398 U.S. 235,

257-58 (1970) (Black, J., dissenting) ; Erie R.R. v. Tompkins, 304

U.S. 64, 77 (1938) ( “ If only a question of statutory construction

were involved, we should not be prepared to abandon a doctrine

so widely applied throughout nearly a century.” ).

14 Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U.S. at 736. Of course, as

the Grove City experience illustrates, there are significant costs

involved in legislatively overruling a decision of this Court. See

supra Part I.

11

reason that “ this Court is surely not free to abandon

settled statutory interpretation at any time a new thought

seems appealing,” 15 is found in “ the deference that this

Court owes to the primary responsibility of the legisla

ture in the making of laws.” 16 The Congress is vested

by Article I of the Constitution with “ all legislative

powers.” The Court properly interprets statutes enacted

by the Congress because interpretation is required to de

cide cases brought before it. However, once rendered, a

statutory interpretation becomes “ an integral part of the

statute.” 17 While the Congress is free to overturn a stat

utory precedent for any reason it sees fit, the judicial

branch is not similarly free to reverse precedents when

ever judges have second thoughts. In Justice Black’s

words:

Altering the important provisions of a statute is a

legislative function. . . . Having given our view on

the meaning of a statute, [the Court’s] task is con

cluded, absent extraordinary circumstances. When

the Court changes its mind years later, simply be

cause the judges have changed, in my judgment, it

takes upon itself the function of the legislature.18

15 Monell v. Department of Social Serv., 436 U.S. at 718 (Rehn-

quist, J., dissenting).

16 Boys Markets, Inc. v. Retail Clerks Union, Local 770, 398 U.S.

at 257 (Black, J., dissenting).

17 Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Ry., 275 U.S. 133, 136 (1927).

18 Boys Markets, Inc. v. Retail Clerks Union, Local 770, 398 U.S.

at 258 (Black, J., dissenting). While the majority in Boys Markets

overturned a statutory interpretation, it did not disagree with

the principle articulated by Justice Black, but differed only on the

application of that principle to the facts of the case. See also Com

missioner v. Fink, 107 S. Ct. 2729, 2737 (1987) (Stevens, J.,

dissenting) ( “ The relationship between the courts or agencies, on

the one hand, and Congress, on the other, is a dynamic one. In

the process of legislating it is inevitable that Congress will leave

open spaces in the law that the courts are implicitly authorized

to fill. The judicial process of construing statutes must therefore

include an exercise of lawmaking power that has been delegated

to the courts by Congress. But after the gap has been filled,

regardless of whether it is filled exactly as Congress might have

12

B. There Are No Special Circumstances in This Case

That Justify Overruling Runyon v. McCrary.

Although the Court does, from time to time, overrule

earlier decisions, the mere fact that the Court might have

reached a different result had it decided the earlier case

has never been thought a sufficient justification for doing

so. Instead, “ [a]ny departure from the doctrine of stare

decisis demands special justification.” 19 And where a

prior statutory precedent is at issue, “ [o]nly the most

compelling circumstances can justify this Court’s aban

donment of such firmly established . . . precedents.” 20

In this case, the factors which the Court heretofore has

considered relevant in determining whether such “ com

pelling circumstances” exist do not support overruling

Runyon.

1. The Interpretation of Section 1981 Adopted in

Runyon v. McCrary Was Not Based Upon an

Incomplete Analysis.

In determining whether to overrule a prior decision,

the Court has sometimes taken into account whether the

decision fully considered competing arguments.21 Here,

consideration of this factor clearly counsels in favor

of leaving Runyon undisturbed.

intended or hoped, the purpose of the delegation has been achieved

and the responsibility for making any future change should rest

on the shoulders of Congress.” ).

10 Arizona v. Rumsey, 467 U.S. 203, 212 (1984).

20 Monell v. Department of Social Serv., 436 U.S. at 715 (Rehn-

quist, J., dissenting). See also Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U.S. at

266 ( “ [T]he careful observer will discern that any detours from

the straight path of stare decisis in our past have occurred for

articulable reasons. . . . [Ejvery successful proponent of over

ruling precedent has borne the heavy burden of persuading the

Court that changes in society or in the law dictate that the values

served by stare decisis yield in favor of a greater objective.” ).

21 See, e.g., Copperweld Corp. v. Independence Tube Corp., 467

U.S. 752, 766 (1984) (overruling previous decisions interpreting

Section 1 of the Sherman Act to reach “ intra-enterprise” con

spiracies: “ [Wjhile this Court has previously seemed to acquiesce

in the intra-enterprise conspiracy doctrine, it has never explored

or analyzed in detail the justifications for such a rule. . . .” ).

13

Runyon’s interpretation of Section 1981 as prohibiting

private contract-related racial discrimination in educa

tion was not an aberration. It evolved from the Court’s

earlier decisions in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392

U.S. 409 (1968), Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation

Association, Inc., 410 U.S. 431 (1973), and Johnson v.

Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454 (1975). In

both Runyon and these prior decisions, the Court fully

and carefully considered the competing arguments.

Jones held that Section 1982 reaches private racial

discrimination in property transactions. The Court an

alyzed in detail the Reconstruction-era legislative history,

which relates to both Sections 1981 and 1982, to deter

mine whether the statute was intended to reach private,

as well as governmental, conduct. 392 U.S. at 422-37.

The Court concluded that the Congress “plainly meant

to secure” the right to purchase or lease property “ against

interference from any source whatever, whether govern

mental or private.” Id. at 424.22 In Tillman, the Court

recognized that Section 1981 reached the conduct of a

private association that operated a neighborhood swim

ming pool. In making that determination, the Court

again recognized the interrelated legislative histories of

Sections 1981 and 1982. The Court concluded that there

was “no reason to construe these sections differently”

under the facts before it. 410 U.S. at 440. Two years

after Tillman, the Court unanimously stated in Johnson

that “ it is well settled among the Federal Courts of Ap

peals— and we now join them— that § 1981 affords a

federal remedy against discrimination in private employ

ment on the basis of race.” 421 U.S. at 459-60.23 * 2

22 This Court has subsequently affirmed Jones on numerous oc

casions. See, e.g., Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb, 107 S. Ct.

2019, 2021 (1987) ; Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Ass’n,

Inc., 410 U.S. at 435; Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396

U.S. 229, 235-38 (1969).

2S The Runyon Court described this statement as “ the square

holding” and the “ unequivocal[ ] ” holding of Johnson. 427 U.S. at

170 n.8, 172. And the United States characterized the statement

14

In 1976, the Runyon Court, citing Jones, Tillman, and

Johnson, concluded that “ [i]t is now well established

that . . . [Section] 1981 prohibits racial discrimination

in the making and enforcement of private contracts.” 427

U.S. at 168. Nevertheless, the Court again carefully re

viewed the legislative history of Section 1981. Id. at

168-71, 174-75. The Court considered and rejected, as

“wholly inconsistent” with its earlier precedents, the argu

ment that Section 1981 reached only state-sponsored dis

crimination. Id. at 178. The Court also rejected the

argument that Section 1981 prohibits only legal rules that

disable minorities from making and enforcing contracts.

See id. at 194 (White, J., dissenting).

Indeed, the Court has so fully and completely considered

the Reconstruction-era legislative history of Section 1981

that, following its decision in Runyon, the Court has

merely incorporated the prior analyses by reference,

rather than “ repeat the narrative again.” 24

Accordingly, Runyon cannot be said to be based upon

an incomplete analysis or less than full consideration of

competing arguments.

2. The Interpretation of Section 1981 Adopted in

Runyon v. McCrary Has Not Been Undercut by

Subsequent Legal Developments.

Another factor the Court has sometimes considered

in determining whether to overrule an earlier decision is

whether the reasoning of the earlier decision has been

undercut by subsequent legal developments. In such cases,

the Court is often making explicit what has been implicit

as the “ratio decidendi” of Johnson. Brief for the United States

as Amicus Curiae at 14, Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976)

(No. 75-62). Johnson was a Section 1981 action against a private

defendant. The actual issue before the Court concerned the ap

plicable statute of limitations. The Court would not have reached

that issue if Section 1981 did not provide a cause of action for

acts of racial discrimination by private parties.

24 General Bldg. Contractors Ass’n v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375,

384 (1982).

15

for some time. The overruling simply culminates a long

process of erosion.25 Similarly, the Court has sometimes

revisited a decision found to be wholly inconsistent with

prior decisions or inconsistent with a parallel line of

authority.26

Runyon's reasoning and holding have not been undercut

by subsequent legal developments. No decision rendered

by this Court has questioned the continuing vitality of the

interpretation of Section 1981 adopted there. On the con

trary, this Court has repeatedly and without exception

treated Runyon as well-settled law.27 28 The Executive

Branch has also consistently supported the interpreta

tion of Section 1981 adopted in Runyon,™ and no de

25 See, e.g., Andreivs v. Louisville & Nashville R.R., 406 U.S.

320, 322 (1972) ( “Later cases from this Court have repudiated

the reasoning' advanced in support of the result reached in [the

earlier decision].” ) ; Boys Markets, Inc. v. Retail Clerks Union,

Local 770, 398 U.S. at 238 ( “ [Subsequent events have undermined

[the] continuing validity [o f the earlier decision].” ). See also

Puerto Rico v. Branstad, 107 S. Ct. 2802, 2809 (1987) ( “ [The ear

lier decision] is the product of another time. The conception of

the relation between the States and the Federal Government there

announced is fundamentally incompatible with more than a century

of constitutional development.” ).

26 See, e.g., Monell v. Department of Social Serv., 436 U.S. at

695 (justifying overruling Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961),

in part on ground that Monroe “was a departure from prior

practice” and inconsistent with a subsequent line of cases “ holding

school boards liable in § 1983 actions. . . . ” ).

27 See, e.g., Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 107 S. Ct. 2617, 2620

(1987) ; Saint Francis College v. Al-Khazraji, 107 S. Ct. 2022,

2026 (1987) ; Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69, 78 (1984) ;

Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 461 U.S. at 596; General Bldg.

Contractors Ass’n v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. at 384; City of Mem

phis v. Greene, 451 U.S. 100, 125 n.38 (1981) ; Great Am. Fed.

Sav. & Loan Ass’n v. Novotny, 442 U.S. 366, 377 (1979) ; Cook

v. Hudson, 429 U.S. 165 (1976) ; McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail

Trans. Co., 427 U.S. 273, 285 (1976).

28 See, e.g., Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Sup

porting Petitioner at 10, Patterson v. McLean Credit Union (No.

87-107) ; Brief for the United States at 38, Goldsboro Christian

16

velopments in the Congress have eroded the reasoning of

Runyon. Indeed, as discussed in Part III, the Congress

has convincingly demonstrated that it fully agrees with

Runyon’s interpretation of Section 1981.

Nor is Runyon a sport in the law. It is neither out of

step with prior decisions, as discussed above, nor incon

sistent with any parallel line of authority in this Court.

3. The Interpretation of Section 1981 Adopted in

Runyon v. McCrary Has Not Proved Confusing

or Unworkable in Practice.

A third factor the Court has considered is whether

the earlier case has caused confusion or created practical

difficulties for the lower courts in applying the law.29

Clearly Runyon has not.

Runyon straightforwardly held that Section 1981

reaches private parties who intentionally discriminate on

Schools, Inc. v. United States, reported as Bob Jones Univ. v.

United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983) (No. 81-1) ; Brief for the

Secretary of Commerce at 20 n.6, Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S.

448 (1980) (No. 87-1007) ; Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae at 7, McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Trans. Co., 427 U.S. 273

(1976) (No. 75-260) ; Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae at 13, Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) (No. 75-62).

29 See, e.g., Swift & Co. v. Wickham, 382 U.S. I l l , 124 (1965)

(overruling earlier statutory decision that “ is in practice unwork

able . . . lower courts have . . . sought to avoid dealing with its

application or have interpreted it with uncertainty” ). See also

Garcia v. San Antonio Metro. Transit Auth., 469 U.S. 528, 546-47

(1985) (overruling National League of Cities v. Usery, 426 U.S.

833 (1976), in part because “ a rule of state immunity from fed

eral regulation that turns on a judicial appraisal of whether a

particular governmental function is ‘integral’ or ‘traditional’ ” had

proved “ unworkable in practice” ) ; Gulf stream Aerospace Co7-p.

v. Mayacamas Corp., 108 S. Ct. 1133, 1140-41 (1988) ( “A half

century’s experience has persuaded us . . . that the rule is . . .

unworkable and arbitrary in practice. . . . [T]he gulf between

the historical procedures underlying the rule and the modern proce

dures of federal courts renders the rule hopelessly unworkable in

operation.” ).

17

the basis of race in the making and enforcement of con

tracts. Since there has never been any question that

Section 1981 also reaches state-sponsored racial discrim

ination, Runyon simply made clear that Section 1981

applies across the board without regard to the identity

or position of the actor. Lower courts, following Runyon,

have not found this general principle to be confusing or

unworkable.30 Of course, this Court’s guidance may be

necessary in fine-tuning that principle and applying it to

specific cases such as this one. But that ongoing process

is not a reason to overrule a general principle already

established.

4. Overruling the Interpretation of Section 1981

Adopted in Runyon v. McCrary Would Frustrate

Legitimate Reliance Interests.

Another factor this Court has considered is whether

“ ‘individuals may have arranged their affairs in reliance

on the expected stability of the decision.’ ” 31 Where there

has been no legitimate reliance on the decision, the Court

may feel less hound by stare decisis.

In Monell v. Department o\f Social Services, 436 U.S.

658, 700 (1978), for example, the Court noted that its

earlier decision holding municipalities immune from suit

under Section 1983, 42 U.S.C. § 1983, could not he legiti

mately relied upon by municipalities because violations

30 See, e.g., Wright v. Salisbury Club, Ltd., 632 F.2d 309, 312

(4th Cir. 1980) ; Manzanares v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 593 F.2d 968

(10th Cir. 1979) ; Hall v. Pennsylvania State Police, 570 F.2d 86,

92 (3d Cir. 1978) ; Brown v. Dade Christian Schools, Inc., 556

F.2d 310, 312 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1063 (1978) ;

Nieto v. UAW, Local 598, 672 F. Supp. 987, 988-89 (E.D. Mich.

1987) ; Miller v. Hall’s Birmingham Wholesale Florist, 640 F. Supp.

948 (N.D. Ala. 1986) ; Moye v. Chrysler Corp., 465 F. Supp. 1189,

1190 (E.D. Mo.), aff’d, 615 F.2d 1365 (8th Cir. 1979); Hollander

v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 450 F. Supp. 496, 499-500 (D. Conn.

1978).

131 Monell v. Department of Social Serv., 436 U.S. at 700 (quoting

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. at 221-22 (Frankfurter, J., dissenting)).

18

of constitutional rights are “ completely wrong” and pub

lic bodies cannot arrange their affairs “ on an assump

tion that they can violate constitutional rights indefi

nitely . . . In contrast, Runyon is a decision which

protects against violations of the statute and provides

relief for them, rather than shielding violators, and reli

ance on it is unquestionably legitimate.

Clearly, individuals “ have arranged their affairs in

reliance on the expected stability of” Runyon’s ruling

that Section 1981 prohibits private racial discrimination

in the making and enforcing of contracts. For example,

parents have made arrangements to place their children

in private schools with the legitimate expectation that

Section 1981 ensures that those schools are not now segre

gated, and will not be segregated in the future. The Con

gress has also legitimately relied on Runyon by enacting

legislation predicated on Section 1981 continuing to have

the meaning given to it in Runyon. See infra Part III.

If Runyon is overruled, this reliance—by individuals

as well as by the Congress— would be frustrated at great

social and emotional cost. The very purpose of Section

1981, like all other civil rights laws, is to change be

havior and, therefore, expectations. The progress wrought

by these laws is considerable and undeniable. The sta

bility of decisions in this area is vital to the success of

the Nation’s effort to eliminate racial discrimination.

Those individuals whose rights are protected by anti-

discrimination statutes should be able to rely on settled

precedent in arranging their affairs, and those whose

conduct is governed by such laws should not be led to

expect that they can escape their legal obligations by

reversals in statutory interpretations.82 83

83 See Patsy v. Board of Regents, 457 U.S. 496, 501 n.3 (1982)

(refusing to overrule prior cases that had refused to read ex

haustion of administrative remedies requirements into Section

1983, in part because “ [o]verruling these decisions might injure

those § 1983 plaintiffs who had foregone or waived their state

administrative remedies in reliance on those decisions” ).

19

5. There Has Been No Relevant Change in Social,

Economic or Other Factual Circumstances Since

Runyon v. McCrary.

Finally, in the constitutional context, the Court has

sometimes overruled an earlier decision on the ground

that some underlying factual circumstance— social, eco

nomic, or otherwise— has changed.33 In Justice Stewart’s

words, “ [a] substantial departure from precedent can . . .

be justified . . . in the light of an altered historic environ

ment.” 34 So far as amici are aware, this factor has

rarely, if ever, been applied in the statutory context and,

in any event, does not apply to Runyon.

No relevant social or economic circumstance has

changed since 1976. If there was a “ factual circum

stance” that influenced the Court’s interpretation of Sec

tion 1981 in Runyon, it was the recognition that “ [t]he

policy of the Nation . . . in recent years has moved con

stantly in the direction of eliminating racial segregation

in all sectors of society.” 427 U.S. at 191 (Stevens, J.,

concurring). That policy has not changed. Today the

nation remains committed to “ the fundamental policy of

eliminating racial discrimination.” 35

* * *

In sum, the factors this Court considers in determin

ing whether to apply stare decisis overwhelmingly coun

sel that Runyon not be overruled. As the Court stated

33 See, e.g., Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522, 537 (1975) (over

ruling decision that had upheld the systematic exclusion of women

from jury service because “ [ i ] f it was ever the case that women

were unqualified to sit on juries or were so situated that none of

them should be required to perform jury service, that time has

long since passed” ) ; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483,

494-95 (1954) (overruling Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537

(1896), in part because the insidious psychological effects of seg

regation on school children “ is amply supported by modern

authority” ).

34 Mitchell v. W.T. Grant Co., 416 U.S. 600, 634-35 (1974)

(Stewart, J., dissenting).

35 Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 461 U.S. at 595.

20

more than 40 years ago in refusing to overrule the

interpretation of another Reconstruction-era civil rights

statute adopted in United, States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299

(1941) :

The construction given § 20 [18 U.S.C. § 242] in the

Classic case formulated a rule of law which has be

come the basis of federal enforcement in this im

portant field. The rule adopted in that case was

formulated after mature consideration. It should be

good for more than one day only. We do not have a

situation here comparable to Mahnich v. Southern

S.S. Co., 321 U.S. 96, where we overruled a decision

demonstrated to be a sport in the law and incon

sistent with what preceded and what followed. The

Classic case was not the product of hasty action or

inadvertence. It was not out of line with the cases

which preceded. It was designed to fashion the gov

erning rule of law in this important field. We are

not dealing with constitutional interpretations which

throughout the history of the Court have wisely re

mained flexible and subject to frequent re-examina

tion. The meaning which the Classic case gave to the

phrase “under color of any law” involved only a con

struction of the statute. Hence if it states a rule

undesirable in its consequences. Congress can change

it. We add only to the instability and uncertainty of

the law if we revise the meaning of § 20 to meet the

exigencies of each case coming before us.

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 112-13 (1945).

The reasoning in Screws applies fully here. It is made

more compelling by the fact, as amici show below, that

this Court’s interpretation of Section 1981 has been af

firmatively approved by the Congress.

III. STARE DECISIS APPLIES WITH SPECIAL FORCE

BECAUSE THE CONGRESS HAS AFFIRM A

TIVELY ENDORSED THIS COURT’S INTERPRE

TATION OF SECTION 1981.

This Court has recognized that the doctrine of stare

decisis has particular force where the Congress has taken

subsequent legislative action consistent with the Court’s

21

interpretation of a statute.86 87 88 Thus, where the Congress

has reenacted a statute, this Court’s prior construction of

the statute is presumed to have been adopted by the Con

gress.37 Likewise, the Court has found congressional ap

proval of a judicial interpretation of a statute in the

Congress’ rejection of legislation that would have over

ruled or limited the reach of the judicial interpretation,38

86 See, e.g., Patsy v. Board of Regents, 457 U.S. at 501 ( “whether

overruling [prior] decisions would be inconsistent with more re

cent expressions of congressional intent” is “particularly relevant”

in deciding “whether prior decisions should be overruled or recon

sidered” ) ; Monell v. Department of Social Serv., 436 U.S. at 696-99.

87 See, e.g., Douglas v. Seacoast Products, Inc., 431 U.S. 265, 279

(1977) (where the Congress has reenacted a statute “ in substan

tially the same form,” the Court “ can safely assume that Congress

was aware of the [interpretation given the statute by the Court

and] . . . that Congress has ratified th[at] statutory interpreta

tion. . . .” ) ; Shapiro v. United States, 335 U.S. 1, 16 (1948)

( “ [T]here is a presumption that Congress, in reenacting the [stat

ute] . . . was aware of the settled judicial construction of the

statut[e]. In adopting the language used in the earlier act, Con

gress ‘must be considered to have adopted also the construction

given by this Court to such language, and made it a part of the

enactment.’ ” ) (quoting Hecht v. Malley, 265 U.S. 144, 153

(1924)).

88 See. e.g., Local 28 of the Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC, 106

S. Ct. 3019, 3047 (1986) ( “Congress was aware that both the

Executive and Judicial Branches had used [race-conscious af

firmative action] as a remedy under [Title VII], and rejected

amendments that would have barred such remedies. . . . [This]

confirms Congress’ resolve to accept prevailing judicial interpreta

tions regarding the scope of Title VII . . . .” ) (opinion of Bren

nan, J.) ; Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258, 283-84 (1972) ( “ [Legisla

tion [that would have overturned judicial interpretation of statute]

has been introduced repeatedly in Congress but none has ever been

enacted. . . . We continue to be loath . . . to overturn those cases

judicially when Congress, by its positive inaction, has allowed

those decisions to stand for so long and, far beyond mere infer

ence and implication, has clearly evinced a desire not to disapprove

them legislatively.” ) ; Joint Indus. Bd. v. United States, 391 U.S.

224, 228 (1968) (refusing to override interpretation of Bankruptcy

Act adopted in United States v. Embassy Restaurant, Inc., 359 U.S.

29 (1959), because section of Act interpreted “was left unchanged

despite the fact that in every Congress since Embassy Restaurant

22

as well as in the Congress’ failure to change the judicial

interpretation in the course of enacting or amending re

lated legislation which reflects the Congress’ awareness

of the interpretation.39

Here, the Congress has both declined to enact legisla

tion that would have effectively repealed Section 1981 as

it relates to employment discrimination, and left Run

yon untouched in the course of enacting related legis-

bills have been introduced to overrule or modify the result reached

in that case” ).

30 See, e.g., Monessen S.W. Ry. v. Morgan, 56 U.S.L.W. 4494,

4496 (June 6, 1988) (where the Congress amended the Federal

Employers’ Liability Act several times, but never attempted to

amend it to provide for prejudgment interest, “ ‘Congress at least

acquiesces in, and apparently affirms’ ” the judicial interpretation

that prejudgment interest is not available under the Act) (quot

ing Cannon v. Univ. of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677, 703 (1979)) ; Square

D Co. v. Niagara Frontier Tariff Bureau, Inc., 476 U.S. at 419

( “ Particularly because the legislative history reveals clear congres

sional awareness of [an earlier interpretation of the statute by

the Court] . . . the fact that Congress specifically addressed this

area and left [the earlier decision] undisturbed lends powerful

support to [its] continued viability.” ) ; Patsy v. Board of Regents,

457 U.S. at 508-09 (Court declined to overturn its earlier decisions

holding that exhaustion of administrative remedies was not man

dated under Section 1983, in large part because the Congress,

in a subsequent enactment of a related statute, had “ clearly ex

pressed its belief” that “ the no-exhaustion rule should be left

standing.” ) ; Lindahl v. OPM, 470 U.S. 768, 782 (1985) ; Herman &

MacLean v. Huddleston, 459 U.S. 375, 385-86 (1983) (The Con

gress’ decision to leave intact one section of securities laws in the

course of revising other sections of securities laws “suggests that

Congress ratified” judicial interpretation given to that section.);

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. v. Curran, 456 U.S.

353, 381-82 (1982) ( “ [T]he fact that a comprehensive reexamina

tion and significant amendment of the [Commodity Exchange Act]

left intact the statutory provisions under which the federal courts

had implied a cause of action is itself evidence that Congress

affirmatively intended to preserve that remedy.” ) ; Missouri v. Ross,

299 U.S. 72, 75 (1936) (The Congress’ permitting a provision of

Bankruptcy Act interpreted by Court to “ stand for many years . . .

although amending . . . the Bankruptcy Act in other particulars . . .

is persuasive evidence of the adoption by that body of the judicial

construction.” ).

23

lation which clearly reflects the Congress’ awareness of

that interpretation. As this Court stated in Lindahl v.

OPM, 470 U.S. 768, 782 (1985), the Congress’ enact

ment of related legislation “without explicitly repealing

the established [case] doctrine itself gives rise to a pre

sumption that Congress intended to embody [the judicial

interpretation in the statute the courts had construed].”

That presumption becomes virtually conclusive where, as

here, the Congress’ actions were predicated on Section

1981 continuing to have the meaning attributed to it by

this Court.

Following this Court’s decision in Jones v. Alfred H.

Mayer & Co., the Congress passed the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972.40 In the course of enacting that

legislation, both the House and Senate considered pro

posals to make Title VII and the Equal Pay Act of 1963,

29 U.S.C. § 206(d), the exclusive federal remedies for

private discrimination in employment. These proposals,

which were ultimately rejected, would have repealed Sec

tion 1981 insofar as it prohibits private racial discrim

ination in employment.

The amendment proposed in the Senate41 generated sub

stantial objections from those who believed that Section

1981 served as a “valuable protection” for those who

might “ fall . . . in the interstices of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964.” 42 Senator Harrison Williams, the floor man

ager and one of the original sponsors of the pending bill,

objected that “ [i] t is not our purpose to repeal existing

civil rights laws,” and noted that to do so “would severely

weaken our overall effort to combat the presence of em

ployment discrimination.” 43 Specifically recognizing the

scope of Section 1981, Senator Williams stated:

40 Pub. L. No. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103 (1972). This Act amended

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq.

41 118 Cong. Rec. 3173 (1972) (Hruska amendment).

42 Id. at 3370 (statement of Sen. Javits).

43 Id. at 3371 (statement of Sen. Williams).

24

The law against employment discrimination did not

begin with title VII and the EEOC, nor is it

intended to end with it. The right of individuals

to bring suits in Federal courts to redress individual

acts of discrimination, including employment discrim

ination, was first provided by the Civil Rights Acts

of 1866 and 1871, 42 U.S.C. sections 1981, 1983. It

was recently stated by the Supreme Court in the

case of Jones v. Mayer, that these acts provide funda

mental constitutional guarantees. In any case, the

courts have specifically held that title VII and the

Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1871 are not mutually

exclusive, and must be read together to provide alter

native means to redress individual grievances.

Mr. President, the amendment of the Senator from

Nebraska [Sen. Hruska] will repeal the first major

piece of civil rights legislation in this Nation’s his

tory. We cannot do that. . . . I believe that to make

title VII the exclusive remedy for employment dis

crimination would be inconsistent with our entire

legislative history of the Civil Rights Act. It would

jeopardize the degree and scope of remedies available

to the workers of our country.44 * 46

Responding affirmatively to Senator Williams’ plea that

the Congress not “ strip from th [e] individual his rights

that have been established, going back to the first Civil

Rights Law of 1866,” 4,5 the Senate rejected the repeal

ing amendment.48

The House Education and Labor Committee similarly

rejected an exclusive remedies provision, explaining that

the Committee wishes to emphasize that the indi

vidual’s right to file a civil action in his own behalf,

pursuant to the Civil Rights Act of 1870 and 1871,

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983, is in no way affected.

. . . [It is] this Committee’s belief that the remedies

available to the individual under Title VII are co

extensive with the individual’s right to sue under the

44 Id. at 3371-72.

« Id. at 3372.

46 Id. at 3373.

25

provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981, and that the two procedures augment each

other and are not mutually exclusive.47

The Committee minority also recognized that “ charges

of discriminatory employment conditions may still be

brought under prior existing federal statutes such as . . .

the Civil Rights Act of 1866 . . . . [0]ur attempt to

amend the Committee bill to make title VII an exclusive

remedy (except for pattern or practice suits) was re

jected.” 48

A substitute bill containing an exclusive remedies pro

vision was proposed in the House during the floor de

bates.49 50 51 52 The sponsor of the substitute explained that

“ there would no longer be recourse to the old 1866 civil

rights act.” 60 Although vigorously opposed,61 the substi

tute bill was adopted by a slim majority in the House.®

In conference with the Senate, however, the House re

ceded and a compromise version of the bill which con

tained no exclusive remedy provision became law.63 The

Congress thus unequivocably manifested its intent to pre

serve the scope of Section 1981 by rejecting efforts to

eliminate the statute’s application to private employment

discrimination.

This legislative history played a significant role in

persuading this Court in Runyon to adhere to its earlier

interpretation of Section 1981:

47H.R. Rep. No. 238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 18-19 (1971).

43Id. at 66.

49 117 Cong. Rec. 31979-80 (1971) (Erlenborn substitute).

50 Id. at 31973 (statement of Rep. Erlenborn).

51 Members objected that the substitute bill would “repeal[]

the Civil Rights Act of 1866 where it touches upon this field,”

id. at 31978 (statement of Rep. Eckhardt), and would “nullify

the Civil Rights Act of 1866 . . . as far as employment discrimina

tion is concerned.” Id. at 32100 (statement of Rep. Hawkins).

52 Id. at 32111-12.

83 H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 899, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. 17 (1972).

26

It is noteworthy that Congress in enacting the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 . . . specifically

considered and rejected an amendment that would

have repealed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, as in

terpreted by this Court in Jones, insofar as it affords

private-sector employees a right of action based on

racial discrimination in employment. . . .

427 U.S. at 174.

In October 1976, after the Tillman, Johnson and Rum-

yon decisions, the Congress again signaled its approval

of this Court’s interpretation of Section 1981 in enacting

the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976.54 55

That Act permits the recovery of attorney’s fees in ac

tions against private parties under Section 1981.5'5 The

House Judiciary Committee summarized the reach of

Sections 1981 and 1982 as follows:

Section 1981 is frequently used to challenge employ

ment discrimination based on race or color. John

son v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454

(1975). Under that section the Supreme Court re

cently held that whites as well as blacks could bring

suit alleging racially discriminatory employment