Plaintiffs' Statement in Opposition to Government's Motion to Intervene Under Section 902

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

7 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Statement in Opposition to Government's Motion to Intervene Under Section 902, 1972. 3386ebed-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7373cca1-3c70-4927-be44-82e82430eaf0/plaintiffs-statement-in-opposition-to-governments-motion-to-intervene-under-section-902. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

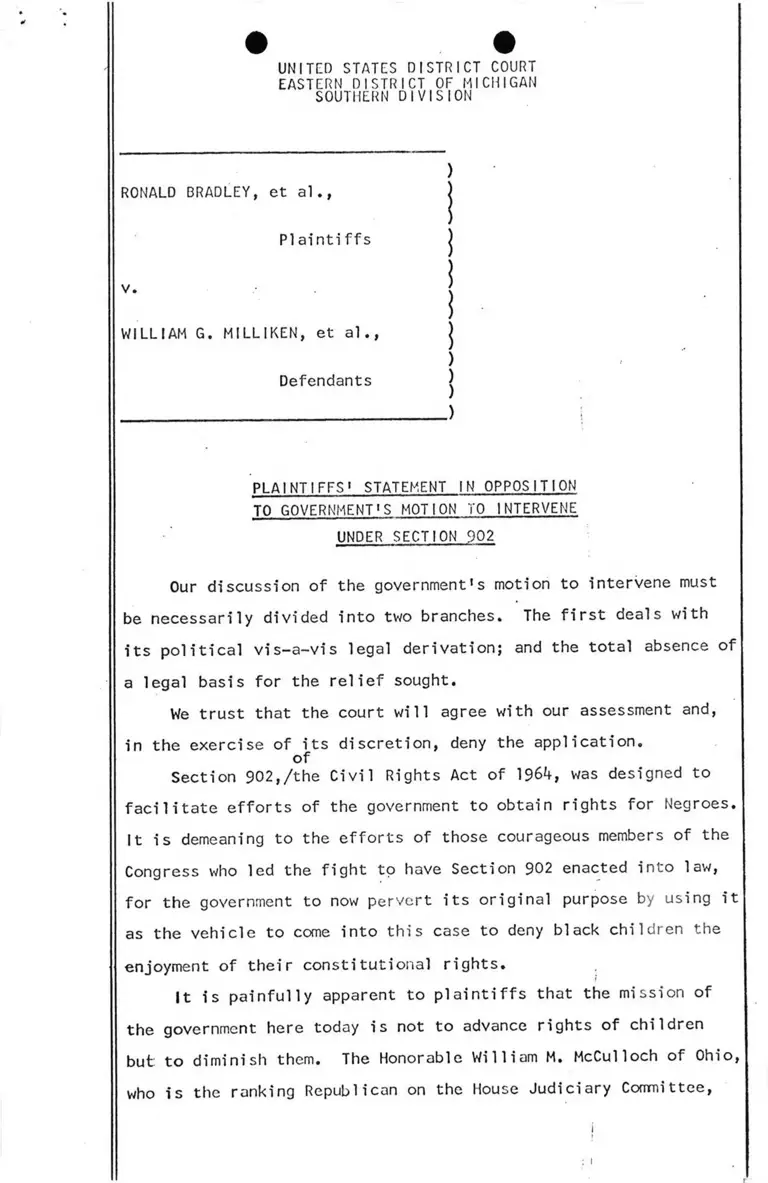

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

PIainti ffs

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

PLAINTIFFS1 STATEMENT IN OPPOSITION

TO GOVERNMENT'S MOTION TO INTERVENE

UNDER SECTION 902

Our discussion of the government's motion to intervene must

be necessarily divided into two branches. The first deals with

its political vis-a-vis legal derivation; and the total absence of

a legal basis for the relief sought.

We trust that the court will agree with our assessment and,

in the exercise of its discretion, deny the application.

of

Section 902,/the Civil Rights Act of 196A, was designed to

facilitate efforts of the government to obtain rights for Negroes.

It is demeaning to the efforts of those courageous members of the

Congress who led the fight to have Section 902 enacted into law,

for the government to now pervert its original purpose by using it

as the vehicle to come into this case to deny black children the

enjoyment of their constitutional rights. .

f

It is painfully apparent to plaintiffs that the mission of

the government here today is not to advance rights of children

but to diminish them. The Honorable William M. McCulloch of Ohio,

who is the ranking Republican on the House Judiciary Committee,

)

i

!

1

I

)

)

)

- 2-

an author of the 196^ Civil Rights Act, and one of the original

sponsors of the Nixon moratorium bill who has since withdrawn his

support, aptly characterized the efforts of the executive branch,

which has led to this motion, when he remonstrated to acting

Attorney General Richard Kleindeinst on April 11. He stated:

"It is with the deepest regret that I sit

here today to listen to a spokeman for a

• Republican administration asking the Con- .

qress to prostitute the courts by obliqat-

' inq them to suspend the equal protection

clause for a time so that Congress may

debate the merits of further slowing down

i and perhaps even rolling back desegregation

in public schools."

This is being done, said the respected Congressman, because,

"some prominent politicians have fueled false fears and raised

false hopes." -

The true basis of the intervention attempt is, as Congressman

McCulloch said, political. Reenforcing that contention are the

words of the President in his March 16th address announcing his

intention to seek a moratorium. The President said:

"I am opposed to busing for the purpose of

achieving racial balance in our schools. I

have spoken out against busing scores of

times over many years. And I believe most

Americans— white and black— share that view.

But what we need now is not just speaking out

against more busing, we need action to stop it,

"The reason action is so urgent is because of

a number of recent decisions of the lower

Federal courts. Those courts have gone too far;

. in some cases beyond the requirements laid down

by the Supreme Court, in ordering massive busing

to achieve racial balance.

- 3 -

"There's no escaping the fact that some

people do oppose busing because of racial

prejudi ce.

"If you agree with the goals I described

tonight to stop more busing now and pro

vide equality of education for all of our

children, 1 urge you to let your Congress

men and Senators know your views so that

Congress will act promptly to deal with

this problem."

This amounted to a call to arms— a call for an attack upon

the rights guaranteed to black people under the Fourteenth Amend

ment. It was a political call for people to force Congress to

browbeat Federal courts into submission. The President's ar.gu-

does

ment, asT ' the argument of the government here, asserts that Con

gress is merely being asked to affect remedies and not substantive

rights.

That brings me to the second branch of our discussion. Those

who argue that Congress has the power to curtail "remedies" as

distinguished from "rights" are engaging in the usual nitpicking

that has characterized statements and theories of the opponents

of school desegregation from 195^ to the present time. Section 1

of the Fourteenth Amendment commands the states to give equal pro

tection of the laws. It would require the most bizarre interpre

tation of that Amendment, as I suggested earlier, for the princi

ple of UBI, JUS, IBI Remedium to not be violated if Congress di

luted the Fourteenth Amendment by passing a law which would pre

vent black children from riding to school where they can enjoy

their rights to a desegregated education.

We assert that the government is asking the Congress to act

illegally. But of more direct concern to us here is that the

attempt at intervention is for the purpose of having this court

aid and abet the illegal scheme.

We maintain that neither the Thirteenth nor the Fourteenth

Amendment givesCongress the power to dilute rights protected by

those Amendments. In Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 86 S. Ct»

1717, 1724 N. 10, we find these words on Section 5 of the Fourteen--

th Amendment:

"Section 5 grants Congress no power to

. restrict, abrogate or dilute these guaran

tees. Thus, for example, an enactment

, authorizing the states to establish racial

ly segregated systems of education would

not be— as required by Section 5— a measure

to enforce the equal protection clause since

that clause of its own force prohibits such

state laws."

As this court so powerfully demonstrated in its ruling on

segregation, racial segregation in Detroit's housing patterns have

made some busing necessary to overcame the deprivation of educa

tional rights of black children. The proposed moratorium' and the

stay sought by the Executive Branch are but naked attempts to

sanction public school segregation by Federal law. It suggests .

the astounding thesis that although the Fourteenth Amendment pro

hibits states from depriving Negroes of their constitutional

rights, Congress is beyond the reach of any constraint and, ac

cordingly, may whittle away constitutional rights with impunity.

The Supreme Court, in Bol 1 ing v 0 Sharpe. 347 U.S. 497, 74 S.

Ct. 693; 98 L„ Ed. 884 (1954), held that: ..

"In view of our decision that the Consti

tution prohibits the states from maintaining

segregated public schools, it would be un

thinkable that the same Constitution would

impose a lesser duty on the federal government."

These and other authorities lead, we submit, to the ines

capable conclusion that Congress is not beyond the reach of the

Constitution; that it lacks power to diminish or curtail consti

tutional rights; and that any legislation, to be constitutionally

permissible, must be shown to be of a nature as will "enforce" •

not interfere with— the constitutional rights.

Webster's Dictionary of the English Language, 1968, offers

this definition of "enforce."

"To give strength to; to add force, emphasis,

or impressiveness to; to put in execution; to

cause to take effect,"

Does the government seriously contend that their aim is to

give strength to; to add force, emphasis, or impressiveness to;

to put in execution; to cause to take effect, the Fourteenth

Amendment rights of black children?

The words of former Associate Justice Arthur J. Goldberg,

spoken just last week to the House Judiciary Committee, are

extremely pertinent. He said that the moratorium bill is plainly

unconstitutional. Furthermore, he characterized the provisions

of the legislation aimed at authorizing stays of court orders,

such as is being sought here, as also being unconstitutional. The

Executive Branch is seeking, says Justice Goldberg, to unconsti

tutionally interfere with the power of the Federal court. That

is what is attempted 'by the legislation. What is even more

alarming is their attempt, without the support of law, to stay

proceedings in this and other District Courts. This brings

America's constitutional system perilously close to destruction.

The next step is a totalitarian state, where rights are

given and taken according to shifting winds and moods of hostile

majorities exercising unbridled power.

That brings me again to the question of the political

motivation that Congress McCulloch has described. The President

and others who seek or soy they seek to halt busing under the

- 6 -

legislative proposals often play the numbers game. In so doing

they cite the number of people who are opposed to busing. They

even have the audacity to quote so-called black spokesmen who are

opposed to busing as justification for enacting curbs. Plaintiffs

here include the NAACP, the largest and oldest and most broad-

based organization in that civil rights field. But even were the

NAACP not in this case, were the plaintiffs not backed by the

broad community support which they enjoy, that would have no

bearing on the constitutional principle here involved,. As long

as one black person wanted redress, he is entitled to it. That

question was settled as far back as 1938 when the Supreme Court,

in Missouri ex rel Gaine.̂ v, Canada, 305 U.S. 377> 59 S. Ct. 232,

83 L. Ed. 208, held that the right to equal protection is a

personal right.

And in considering the Executive Branch's political motiva

tion, let us also remember Cooper v. Aaron, the famous Little

Rock case, in which the court reminded us all that community

hostility or disagreements over court orders, are not legitimate

reasons for abandoning enforcement of constitutional rights.

Here we are eleven days short of eighteen years after Brown,

trying to keep the Executive Branch and the Congress from blocking

the school house door, to black children. That is precisely what

this motion to intervene seeks to do. It is part of the strategy

of nullifying the Fourteenth Amendment by assaulting the courts

and the rights of litigants who resort to courts for the vindi

cation of their rights.

Plaintiffs here, and all persons who feel that courts and

the law can be instruments for the enforcement of. rights, urge

this court to reject the move by the government to, in effect,

pervert Section 902, nullify the Fourteenth Amendment, and to

interfere with the power of courts to redress constitutional

violations. *

Nathaniel R. Jones, Esq.

Louis R. Lucas, Esq.

William E. Caldwell, Esq.

E. Winther McCroom, Esq.

Norman J. Chachkin, Esq.

J. Harold Flannery, Esq.

Paul Dimond, Esq.