Lockett v. Board of Education, Muscogee County School District, Georgia Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 29, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lockett v. Board of Education, Muscogee County School District, Georgia Brief of Appellants, 1967. 9d233473-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/74f1db9a-0cdb-4b5f-8c36-fdca9858a91f/lockett-v-board-of-education-muscogee-county-school-district-georgia-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

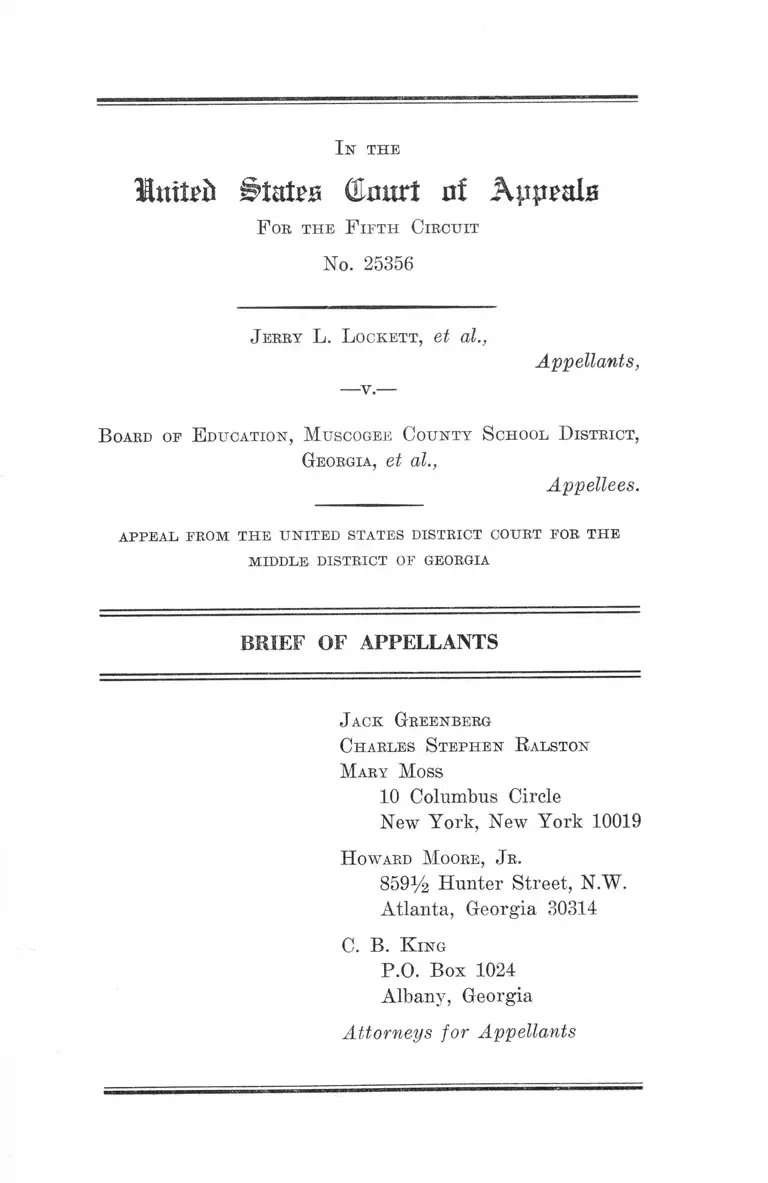

1 ixxUb States (Emtrt of Appeals

F ob th e F if t h C ircuit

No. 25356

I n th e

J erby L . L ockett , et al.,

Appellants,

B oard of E ducation , M uscogee C ou nty S chool D istrict,

Georgia, et al.,

Appellees.

A PPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

M IDDLE D ISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

C harles S teph en R alston

M ary M oss

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H oward M oore, J r .

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

C. B. K ing

P.O. Box 1024

Albany, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of the Case ....................................................... 1

1. History of this litigation .................................. 1

2. Present status of school desegregation ........... 3

A. Pupil desegregation—the choice period .... 3

B. Faculty desegregation ........................ 6

C. Other aspects of the school system .............. 8

3. The District Court’s Order .................................. 9

Specification of Error .................................................. 10

A k g u m e n t :—

I. The Requirements of Jefferson County Ap

ply to All School Districts in This Circuit

Against Which School Desegregation Suits

Are Pending ........................................................ 10

II. The Present Plan for Desegregation Is Not

in Compliance With the Jefferson County

Decree .................................................................... 12

III. The Grounds set Forth by the District Court

for Denying Belief Were Inadequate ............. 16

C onclusion ......................................................................................... 19

Certificate of Service 20

11

T able of C ases

PAGE

Acree, et al. v. County Board of Education of Rich

mond County, Ga. (No. 25136, August 31, 1967) ..... 11

Banks v. St. James Parish School Board (No. 25375,

Nov. 20, 1967) .................................................................. 11

Bivins v. Board of Education and Orphanage for Bibb

County, Ga. (No. 24753, May 24, 1967) ..................... 11

Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage

for Bibb County (M.D. Ga,, CA No. 1926, Oct. 20,

1967) ................................................................................ 13,14

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board (No.

24861, July 24, 1967) ...................................................... 11

George v. Davis, Pres, of East Feliciana Parish School

Board (No. 24860, July 24, 1967) .............................. 11

Hall, et al. v. St. Helena Parish School Board; James

Williams, Jr., et al. v. Iberville Parish School

Board; Boyd, et al. v. The Pointe Coupee Parish

School Board; Terry Lynn Dunn, et al. v. Livingston

Parish School Board; Welton J. Charles v. Ascen

sion Parish School Board, et al.; Thomas, et al. v.

West Baton Rouge Parish School Board, et al. (Nos.

25092 consolidated, August 4, 1967) ........................... 11

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F. Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala. 1967), aff’d sub nom, Wallace v.

United States,------ U.S. —— (Dec. 4, 1967) ............. 17

Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County

School District, Ga., 342 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1965) ..._2,11,

17,18

Ill

PAGE

Thomie v. Houston County Board of Education, Ga.

(No. 24754, May 24, 1967) ...................... ....... ............. 11

United States of America and Linda Stout, et al. v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, et al., 372 F.2d

836 (5th Cir. 1966) ...................................... 2,10,11,15,16

United States of America and Linda Stout, et al. v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, et al., 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir. 1967) .............. ............ 1,3,4,5 ,6,8,9,10,12,

13,14,15,17,18

I n th e

United States (Hour! of Appeals

F ob th e F if t h C ircuit

No. 25356

J ebby L . L ockett, et al.,

Appellants,

B oard of E ducation , M uscogee County S chool D istrict,

Georgia, et al.,

Appellees.

A PPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

M IDDLE D ISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of Honorable J. Robert

Elliott, Judge of the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Georgia, denying appellants’ motions

for an order entering a decree pursuant to the decision in

United States of America and Linda Stout v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, et al. with regard to the

Board of Education of the Muscogee County School Dis

trict, Georgia.

1. History of this litigation

In 1963, the Board of Education of Muscogee County

instituted a desegregation plan for its schools (R. 1-4).

2

Subsequently, this action against the Board and school

officials was filed on January 13th, 1964, by Negro students

and parents in the City of Columbus and Muscogee County.

The suit sought to enjoin the continued operation of a

bi-racial school system and challenged the appellees’ de

segregation plan as inadequate on a number of grounds.

On April 22, 1964, the district court denied plaintiffs-

appellants’ motion for a preliminary injunction and ap

proved the school board’s plan. An appeal was taken to

this Court and the case was affirmed as to the denial of

an injunction, but was reversed as to the approval of the

plan. Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County

School District, Ga., 342 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1965). This

Court held that it was not error to refuse to enjoin the

school board because of its “ intention to effectuate the

law,” 342 F.2d at 229. The plan for desegregation, how

ever, could be approved only if it conformed with the then

current minimal standards enunciated in other decisions

of the Court. Those standards included the giving of ade

quate notice of the plan and the abolition of any dual or

bi-racial school attendance system. 342 F.2d at 228-229.

Desegregation of the teaching and administrative per

sonnel would not be immediately required, but might be

more appropriately considered by the school board, and

the court, if necessary, after the desegregation plan as to

pupils had progressed to some extent. Subsequently, the

appellee school board amended its plan from time to time,

the most recent amendment being on January 31, 1967

(R. 5-6).

In January and February, 1967, subsequent to the first

decision in United States of America and Linda Stout v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (1966),

appellants filed motions for summary judgment and for

3

further relief asking that a Jefferson County decree be

entered (R. 7-30).1 In May, 1967, after the en banc affirm

ance of Jefferson (380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967)), appel

lants filed a supplementary motion renewing their earlier

motions and asking that either a Jefferson County decree

be entered or that an immediate hearing- be granted (R.

32-33). The appellees filed a response in which they ques

tioned the necessity and desirability of ordering the

Muscogee County school system to conform to all of the

Jefferson County requirements (R. 35-38).

2. Present status of school desegregation

The District Court held a hearing on appellants’ motions

on June 15,1967. At the hearing, the school board accepted

appellants’ position that the burden was on it to show why

a Jefferson County decree should not be entered (R. 40).

This section of the statement will set out the evidence

developed by testimony and exhibits relating to the present

plan and the extent of desegregation under it.

A. Pupil desegregation— the choice period

The Muscogee County school system has 49,384 pupils,

27.5 percent of whom, or about 13,000, are Negroes (R. 41,

60). As of November, 1966, there were 316 Negro students

attending previously all-white schools in regular classes

(R. 61). Fifteen of these students graduated in June, 1967,

and 550 more made choices to go to white schools in

1967-68. Thus, the superintendent estimated that there

would be 851 attending regular elementary, junior, and

1 The motion for summary judgment was an attempt to have entered

immediately those portions of the Jefferson County decree dealing with

the choice period in time for the school year 1967-68. The motion for

further relief requested the entering of the rest o f the Jefferson County

decree.

4

senior high school classes in the 1967-68 school year (R. 65).

In addition, there were 112 in the adult school and man

power program and 275 in the Columbus Area Vocational

Technical Schools with whites (Ibid).2 Thus, only 9.7%

of the total Negro enrollment was attending desegregated

schools, with a smaller percentage in desegregated regular

classes. To the superintendent’s knowledge, only one white

pupil was attending a Negro school (R. 75).

The choice period for the 1967-68 school year was made

pursuant to the resolution of January 31, 1967, amending

the desegregation plan (R. 5-6). Although the resolution

provided for a period from March 1 through March 31,

1967, it was extended through April 3 (R. 43). An ex

planatory letter, copy of the resolution and choice form

were sent home to parents by pupils (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2).

Choice forms were returned to the principals of the indi

vidual schools; only those requesting a change of school

were sent to the superintendent’s office for processing.

Seven thousand seven hundred fifty three (7,753) such

forms were processed by the central office (R. 45).3 Of

these, 550 were requests by Negro pupils to be trans

ferred to formerly all-white schools.

A central question was whether the plan involved the

mandatory exercise of choice by all pupils as required by

Jefferson. The language of the January 31 resolution and

the explanatory letter does not require that every pupil

make a choice (see, Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2; R. 5) as does

2 In his opinion, the district judge stated that there would be 1250

Negro pupils attending formerly all-white schools in September, 1967

(R. 124). However, it is clear that this figure is the total of regular

and special pupils.

3 All choices had been acted upon at the time of the hearing except for

those of 16 white students requesting transfer to other white schools (R.

125).

5

the Jefferson County decree. 380 F.2d 385, 391, 395.

Bather, it only says that they may choose to attend any

school if they so wish.4 Pupils who did not make a choice,

according to the resolution, “ shall register and enroll at

the school the pupil is now attending or at a school in

the area in which said pupil’s residence is located” (R. 5).

The procedure used for assignment of pupils who made

choices supports the conclusion that there was no manda

tory choice. There was no central processing of all choice

forms; only those requesting a different school than that

attended were sent to the main office (R. 67). In fact, the

superintendent did not know whether every student had

filled out a choice form, or even whether any pupils who

wished to stay in the same school did so. It was simply

assumed that students who did not bring in a choice form

chose the school they already attended (R. 65-67). The

superintendent admitted, in essence, that students who

wished to stay where they were were not required to make

a choice (R. 68).

The absence of mandatory choice and a lack of central

processing of all choices was further shown by the testi

mony of a Negro parent. He had sent in a form choosing

a white school which was denied for overcrowding. He

made a second choice which was similarly denied.5 Upon

a third application his child was assigned to a white school

(R. 105-112; Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 3, 4, and 5). The superin

tendent’s office could not have known whether all the pupils

already in the first two schools had made choices within

4 In contrast, the resolution and explanatory letter state that new

pupils must make a choice of school at the time of enrollment (R. 5-6;

plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2).

5 There was a conflict in the testimony of the parent and the super

intendent over whether or not the parent was informed of a school that

was not overcrowded after his first choice was denied (R. 107; 113).

6

the choice period, since it received only the forms request

ing changes (E. 86-88). Thus, preference in assignment

was given to pupils already attending the school whether

or not they had made choices, a practice not in conformity

with the Jefferson County decree.

B. Faculty desegregation

The evidence was clear that there was to he no desegre

gation of regular classroom teachers for the year 1967-68

(E. 76-77). No Negro teachers were teaching in regular

white classes or vice versa (E. 74). The only faculty de

segregation was in special classes6 and in summer pro

grams funded by the Federal Government where receipt

of funds was conditioned on such desegregation7 (E, 76-

77). Since 1966, general and group faculty meetings have

been integrated (E. 49). Plans were under way to inte

grate the white and Negro teachers’ professional associa

tions (E. 49-50).

There were no plans, however, for the integration of

the regular classroom faculties. There are 1828 teachers

in the system, 500 of whom are Negro (E. 45). It was

claimed that all teacher contracts and assignments had

been made for 1967-68 and it could create difficulties to

comply with the Jefferson County requirement for this

6 There is one Negro teacher at the Reading Center, one Negro con

sultant in English, one part-time Negro teacher in the Adulx Education

Program, one Negro guidance counsellor at the vocational technical school,

one Negro teacher in audio-visual aids, and two white teachers in Radio

and TV at the Negro trade school (R. 47).

7 There were 8 white and 3 Negro teachers, 4 wnite and 1 Negro

examiners, 4 white and 2 Negro bus drivers, and 3 white and 1 Negro

clerks in the integrated summer diagnostic center. In the summer remedial

program there were 3 white and 2 Negro principals and 38 white and

34 Negro teachers. In the tutoring program there were 28 white and 27

Negro teachers; however, only three of the twelve schools in the program

had integrated faculties (R. 48-49).

7

year (R. 52-53, 58). However, it was admitted that the

system had 88 vacancies, evenly distributed between the

65 schools in the system, but there was no plan to fill the

vacancies in the white schools with Negro teachers or vice

versa (R. 77-79).

The superintendent testified that he had not asked any

teachers to integrate faculties, even though he knew of

some that would be willing to do so ; he had not talked

with even 100 of the more than 1800 teachers in the system

to find out who would be willing to integrate faculties; no

attempt had been made to explain what would have to be

done or to otherwise prepare the way for such desegrega

tion (R. 82-83). Teachers applying for positions were

not informed that they might be assigned to schools with

faculties and student bodies of the opposite race (R. 77-

78); nor were white student teachers assigned to Negro

schools or Negro to white (R. 78).

It was clear that neither the superintendent nor the

school board had any plans or intended to make any plans

for faculty desegregation until some indefinite time in the

future when pupil desegregation would be completed (R.

83-84; 97-98; 104-05).8

8 The superintendent, the president of the Board of Education, and the

chairman of the committee of the Board entrusted with desegregation

testified, respectively, as follows:

1. Superintendent:

Q. So, in fact, you have not really done much of anything of

much substance to prepare the way for desegregation of the regular

classroom teachers in your system? A. No, the emphasis has been

on pupils up to this point, which we tried to do without confusion

and chaos in our schools.

Q. Do you have any plans now to do any o f these things that I ’ve

mentioned? A. No, I have none to announce at this time (R. 83) ;

2. President:

Q. Mr. Kinnett, as President of the Board of Education, have you

and other members of the Board informally or formally in meeting

8

C. Other aspects of the school system

Additional evidence bearing on other Jefferson County

requirements was introduced. The superintendent testi-

discussed the question of faculty desegregation? A. Oh naturally,

we discussed it.

Q. And have you discussed making plans? A. We have not dis

cussed making any plans yet because the Fifth Circuit Court in

dicated to us, when our case was before them, which was the Lockett

case, that the faculty would come later. In fact, as I recall, hearing

one of the Judges make the statement that they weren’t interested

in faculty at this time. I believe that’s possibly the exact words.

# » #

Q. But you regarded the Fifth Circuit opinion as allowing you

not to discuss or make future plans for faculty desegregation? A.

Well, we didn’t feel that until such time as we completed the integra

tion of the children, the pupils, that we had an obligation to go into

that.

# # #

Q. In view of those motions and in view of Jefferson County

opinion, did you or the members of the Board generally feel that

you should make any plans for faculty desegregation? A. No, very

frankly, we or I felt personally that the time had not arrived when

we were obligated to do it.

Q. What, sir, specifically is your personal attitude toward integra

tion of the faculties in the School System? A. I think when the

time comes and we can do it and maintain the quality of education,

I think that will be the time.

Q. Well, how far in the future do you see this time coming?

A. Well, I ’m not an educator but I would say not any sooner than

we can do it and still maintain quality education for all children

(R. 97-98);

3. Chairman:

Q. What is your specific attitude toward racial integration of

faculty? A. I am not against it at the proper time.

Q. And when is that, sir? A. It’s the next step.

Q. And when is the next step, as you envision it? A. I would say

that we will begin thinking about that very seriously— we finish the

pupil integration this year and I think that will be one of the next

steps for consideration probably in 1968.

Q. I see. And how long do you envision you will have to think

about it, after you commence thinking about it in 1968? A. I ’m

one member of the committee, I think when we begin to think about it,

we’ll come up with some plan.

Q. In the how distant future, sir? A. In ’68, next year.

Q. Next year you think you will? A. Yes.

Q. You will start thinking about that at that time and you’ll

up with something? A. Sure, I think we will (R. 104-05).

come

9

fled that teacher-pupil ratios in the schools were the same

(R. 46); that all classes would be desegregated in Sep

tember of 1967 {Ibid) ; that athletic and band activities in

desegregated schools were integrated (R. 50-51); parent-

teacher meetings and commencement exercises were inte

grated (55-56); and all schools were accredited (R. 41-42).

On cross-examination he testified that at one Negro school

an old wooden building had been and might still be used

as a classroom (R. 91-92); that segregated social clubs

were allowed to use school facilities (R. 92-94). Evidence

was also adduced as to the routing of school buses within

the system (R. 89-91).

3. The District Court’s Order

On August 15, 1967, the district court handed dawn its

order denying appellants any injunctive relief, on the

ground that the school board was “ earnestly striving to

comply with constitutional requirements in the operation

of its school and is successfully doing so” (R. 130-131).

The only requirement as to pupil desegregation imposed

by the court was that “ the choice period in 1968 and the

manner and means of conducting it shall be in compliance

with the rules prescribed in Jefferson” (R. 129). The

court also stated that the school board should continue

to extend the desegregation of faculties in the coming

school year, and that “ if the action taken by the Board

in this regard is not consistent with that required by

Jefferson and other cases of the Court of Appeals, it

will be necessary for this Court to enter such other orders

as are required to bring about such compliance.” How

ever, the court felt “ that it is not necessary at this time

to enter an order requiring specific action in addition to

that which has already been accomplished by the Board”

(R. 130).

10

A notice of appeal to this Court was filed on Septem

ber 7, 1967 (E. 132). Subsequently, a motion for summary

reversal was filed by appellants, but was, in effect, denied

by a panel of this Court which rather ordered an ex

pedited appeal.

Specification of Error

The court below erred in refusing to enter an order

requiring the Muscogee County School , Board to comply

in all respects with the decision and decree in Jefferson

County.

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Requirements of Jefferson County Apply to All

School Districts in This Circuit Against Which School

Desegregation Suits Are Pending.

In the first opinion in United States of America and

Linda Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372

F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), adopted by the Court en banc,

380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), this Court stated:

[T]he provisions of the decree are intended, as far

as possible, to apply uniformly throughout this circuit

in cases involving plans based on free choice of

schools. School boards, private plaintiffs, and the

United States may, of course, come into court to

prove that exceptional circumstances compel modifi

cation of the decree. . . . Other schools have earlier

court-approved plans which fall short of the decree.

On motion by proper parties to re-open these cases,

11

we expect these plans to be modified to conform with

our decree. 372 F.2d at 894, 895.

In at least 12 instances this Court has enforced this

language by granting summary reversals of refusals of

district courts to enter Jefferson County decrees. Bivins

v. Board of Education and Orphanage for Bibb County,

Ga., Thomie v. Houston County Board of Education, Ga.

(Nos. 24753 and 24754, May 24, 1967); George v. Davis,

Pres, of East Feliciana Parish School Board, Carter v.

West Feliciana Parish School Board (Nos. 24860 and

24861, July 24, 1967); Hall, et al. v. St. Helena Parish

School Board; James Williams, Jr., et al. v. Iberville Parish

School Board; Boyd, et al. v. The Pointe Coupee Parish

School Board; Terry Lynn Dunn, et al. v. Livingston

Parish School Board; Welton J. Charles v. Ascension

Parish School Board, et al.; Thomas, et al. v. West Baton

Rouge Parish School Board, et al. (No. 25092 consolidated,

August 4, 1967); Acree, et al. v. County Board of Educa

tion of Richmond County, Ga. (No. 25136, August 31,

1967); Banks v. St. James Parish School Board (No. 25375,

Nov. 20, 1967). The purpose of the rule thus enunciated

and enforced is clear: to bring about substantial uni

formity between court-ordered and HEW-directed school

desegregation throughout this Circuit.

The present case comes squarely within the language

of Jefferson County. The Muscogee County school system

has been operating under a court-approved freedom of

choice plan. See Lockett, et al. v. Board of Education of

Muscogee County School District, Georgia, et al., 342

F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1965). Appellants contend that: (1) the

plan for desegregation involved herein does not comply

in any substantial way with the Jefferson County decree;

and (2) there has been no showing of any circumstances,

12

exceptional or otherwise, to justify the school system not

being required to bring its plan into full confirmity with

that decree.

II.

The Present Plan for Desegregation Is Not in Com

pliance With the Jefferson County Decree.

Initially, it is clear from the evidence in this case that

the present plan deals only with pupil desegregation. The

resolutions of the school board speak only to that question,

and the testimony of the superintendent and school board

members show conclusively that there is no plan for faculty

desegregation.

The desegregation plan under which the Muscogee County

school system is now operating differs from the Jefferson

decree and is deficient in the following respects:

(1) The provisions for the exercise of choice have not

been made specific by the district court’s order, partic

ularly with regard to mandatory exercise of choice and

the question of priority given because of prior attendance

(see, corrected decree, sections 11(b) and (d), 380 F.2d

at 391). Indeed, the testimony of the superintendent (R.

65, 85-86) demonstrates the necessity for entering the

detailed provisions of Jefferson so there will be no mis

understanding on the part of school officials as to the

procedure they must follow.

(2) The plan does not have the provisions contained in

Section IV of the Jefferson decree (380 F.2d at 393)’

setting restrictions on the permitting of transfers.

(3) The provisions prohibiting the segregation of or

discrimination against students on account of race in all

13

services, facilities, activities and programs are absent

(Section Y, 380 F.2d at 393).

(4) Section VI (380 F.2d at 393-94), requiring that

Negro schools be equalized, that reports be made to the

district court of pupil-teacher ratios, pupil-classroom

ratios, and per-pupil expenditures, and remedial programs

be provided, is absent. In Jefferson I, the Court put spe

cial emphasis on the need to equalize school facilities in

order to make desegregation under freedom of choice plans

a reality (372 F.2d at 891-92). Of particular importance

are the reporting provisions which will provide the court

and parties with information essential to the continuing

supervision of the progress of the plan.

(5) Section II(n ) (380 F.2d at 392), requiring the re

routing of bus lines where necessary, is absent.

(6) Section VII (380 F.2d at 394), placing an affirma

tive obligation on the school board to locate new schools

and expand existing schools “with the objective of erad

icating the vestiges of the dual system” is absent. The

importance of this provision being entered, with its im

position of a present and continuing obligation on the

school board in planning school construction, cannot be

stressed too much. It is best illustrated by the recent

order of the district court in Bivins v. Board of Public

Education and Orphanage for Bibb County (M.D. Ga.,

C.A. No. 1926, Oct. 20, 1967). In Bivins, District Judge

Bootle had similarly refused initially to enter the entire

Jefferson County decree. After a summary reversal by

this Court on May 24, 1967, the decree was entered, in

cluding the school construction provision. Subsequently,

in September, 1967, the plaintiffs in that case tiled sup

14

plementary pleadings to enjoin the construction of a high

school just prior to the contracts for construction being

let. Plaintiffs alleged, and proved, inter alia, that the

school was to be constructed in a Negro neighborhood,

would have an all-Negro student body and would, there

fore, have the effect of promoting segregation, rather than

integration as required by the Jefferson County decree.

The district court enjoined the construction in the planned

location. In his order, the judge stressed that the order

entering the Jefferson County decree was applicable to

the proposed construction, that it imposed an affirmative

obligation on the school board, and that by enjoining the

construction the court was, by supplementary order, en

forcing the obligation thus imposed. In other words, Sec

tion VII is of vital importance in making explicit and

binding a present and future requirement to plan all school

construction so as to bring about maximum integration.

(7) Section VIII (380 F.2d at 394), the provision re

quiring immediate specific steps toward the desegregation

of faculties so that the faculty and staff of each school is

not composed exclusively of members of one race, is absent.

To date there has been very little done to effect faculty

desegregation. The testimony of the superintendent re

vealed that there are no teachers teaching or assigned to

schools to teach in a classroom situation where they are

in racial minority (R. 74). Progress in faculty desegrega

tion has been limited to integrated staffs in special classes

and in summer programs heavily funded by the Federal

Government which requires such programs to be inte

grated as a prerequisite to the receipt of funds (R. 76-77).

Eighty-eight teacher vacancies exist in the system about

evenly distributed between predominantly Negro and

predominantly white schools but there are no plans to

15

fill vacancies in predominantly white schools with Negro

teachers or to fill vacancies in predominantly Negro schools

with white teachers (R. 77-79). There has been no con

certed attempt on the part of the school administration

to find out whether there are teachers in the system who

would be willing to teach in a school predominantly not of

their color if they were asked (R. 82-83). There are, in

fact, no plans to bring about regular classroom desegrega

tion (R. 81-84).

The district court’s order relating to faculty desegrega

tion is clearly insufficient. It approves the wholly inade

quate steps taken to date and only indicates that if future

action is not consistent with Jefferson then further orders

may be entered (R. 129-30). This is in sharp contrast to

the detailed requirements of Jefferson which order a

significant beginning to regular classroom desegregation

immediately.

(8) Finally, the provisions of Section IX (380 F.2d at

395), requiring periodic reports to the opposing party and

the district court on the choice period, the progress of

the desegregation plan and faculty desegregation, is absent.

The importance of this provision was stressed by this

Court in Jefferson I :

Scheduled compliance reports to the court on the

progress of freedom of choice plans are a necessity

and of benefit to all the parties (372 F.2d at 892).

And, it continued:

What the decree contemplates, then, is continuing

judicial evaluation of compliance by measuring the

performance—not merely the promised performance—

of school boards in carrying out their constitutional

16

obligation “to disestablish dual, racially segregated

school systems and to achieve substantial integration

within such systems.” 372 F.2d at 895.

III.

The Grounds set Forth by the District Court for

Denying Relief Were Inadequate.

At the hearing below appellee school board accepted

appellants’ position that the burden was on it to show

why the Jefferson County decree should not be entered

(R. 40). The language of Jefferson I quoted above (372

F.2d at 894, 895) clearly required the board to make such

a showing. Appellants contend that this burden was not

carried, but that the evidence, as set out above, clearly

required the entrance of a Jefferson County decree in its

terms.

The importance of the omitted portions of that decree

has been pointed out above. More generally, appellants

urge that the standard intended to be applied by this

Court in all school cases is:

The only school desegregation plan that meets con

stitutional standards is one that works. # * * The

question to be resolved in each case is : How far have

formerly de jure segregated schools progressed in

performing their affirmative constitutional duty to

furnish equal educational opportunities to all public

school children! 372 F.2d at 847, 896.

Under any standard of measurement the plan in this

case has not worked in any substantial way. Only 851 out

of 13,000 Negro pupils are attending regular classes with

white children. There is no desegregation of regular class

17

room teachers. White schools remain white schools and

Negro school remain Negro schools.

No reason was given by appellees or by the district court

why the Muscogee County schools should not conform to

the same standards and requirements as other systems

in Georgia and, indeed, every school system in the neigh

boring state of Alabama (see, Lee v. Macon County Board

of Education, 267 F.Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1967), aff’d

sub nom., Wallace v. United States,------U .S .------- (Dec. 4,

1967)).

The stated reason for the district court’s action was that

the school board had been acting in good faith and had

amended its plan to keep ahead of the schedule for deseg

regation set by the courts (E. 130). The presence or

absence of good faith on the part of the school board is,

appellants urge, irrelevant to the question of whether the

school board’s plan is adequate and whether the board

should be required to upgrade it to Jefferson County

standards. The district court relied heavily on this Court’s

decision in the earlier appeal in this case, Lockett v. Board

of Education of Muscogee County School District, 342 F.2d

225 (5th Cir. 1965). However, at that time all that deseg

regation plans involved was the initiation and implemen

tation of free choice provisions. This Court was not re

quiring the carrying out of a detailed plan for overall

integration and dissolution of the dual school system.

Given the relative simplicity of plans, reliance then on a

demonstrated good faith rather than the granting of an

injunction was appropriate.

The Jefferson decree requires something more. Eequire-

ments for school construction, equalization of facilities,

faculty desegregation, and reporting must be imposed

so that they may be enforced if necessary. The only

18

effective way for ensuring the elimination of all vestiges

of segregation is to give Negro plaintiffs and the courts

the proper tools—the specific and detailed provisions of

the Jefferson County decree.

Further, even assuming that good faith efforts by the

school board justified the denial of injunctive relief, the

district court’s reliance on this Court’s earlier decision

to deny appellants’ request that the current plan be

amended in all respects to meet Jefferson County stan

dards was clearly misplaced. In that decision, this Court

affirmed the district court’s denial of appellants’ motion

for an injunction but reversed and remanded insofar as

the school board’s plan did not comply with the then cur

rent standards for school desegregation established by

decisions of the Court (342 F.2d 225, 228-29). Here, again,

appellants are seeking the upgrading of the school board’s

plan, and again, the district court should be instructed to

require such an upgrading. This should be done by the

entering of the specific Jefferson County decree, the cur

rent standard established by this Court as the minimum

requirement for all freedom of choice plans in this Circuit.

19

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the court

below should be reversed and the cause remanded with

instructions to enter a plan in conformance with this

Court’s opinion and decree in Jefferson County.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Charles S teph en R alston

M ary M oss

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H oward M oore, J r .

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

C. B. K ing

P.O. Box 1024

Albany, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

20

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that the undersigned, one of the attor

neys for appellants, served copies of the foregoing Brief

for Appellants on the attorneys for appellees, J, Madden

Hatcher, Esq., and A. J. Land, Esq., P.O. Box 469, Colum

bus, Georgia, by depositing the same in the United States

mail, air mail, postage prepaid.

Done this ----------day of December, 1967.

Attorney for Appellants

M EIIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C • ?g§^> 21?