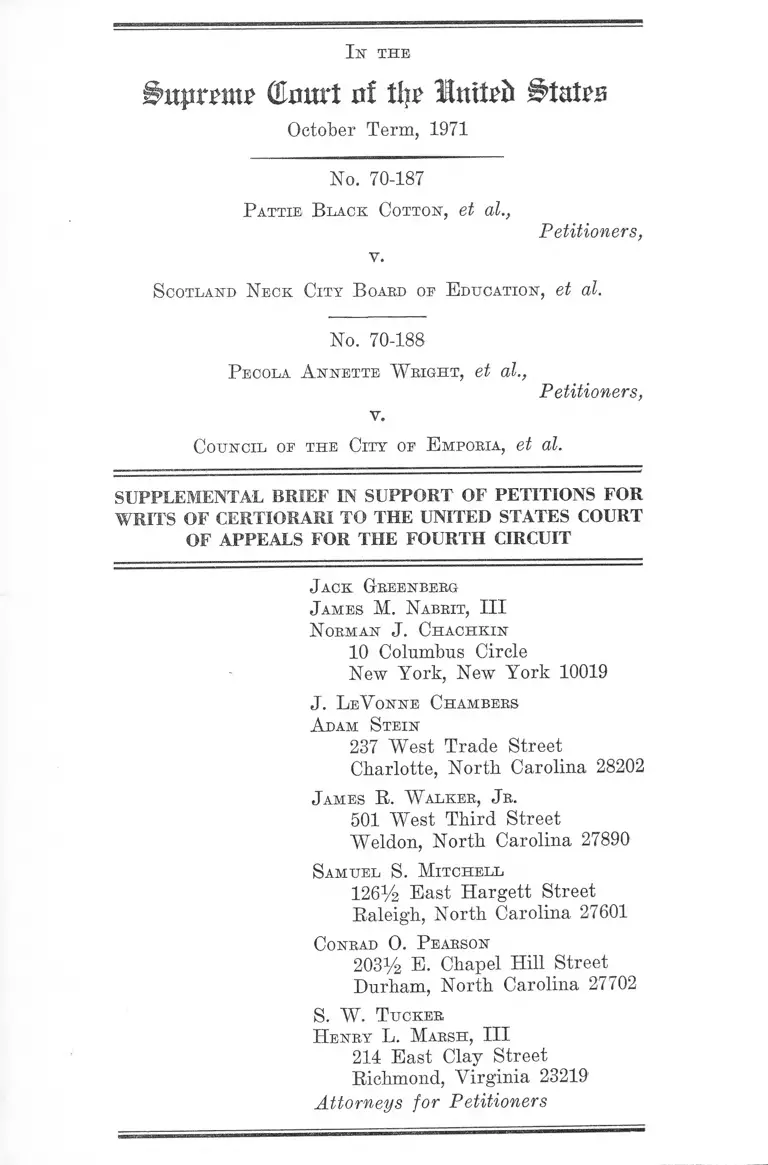

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia Supplemental Brief in Support of Petitions for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia Supplemental Brief in Support of Petitions for Writ of Certiorari, 1971. c48a0e91-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/762d613e-8258-469e-a927-75dc27febcdb/wright-v-council-of-the-city-of-emporia-supplemental-brief-in-support-of-petitions-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

&npvnm GImtrt itf IV States

October Term, 1971

No. 70-187

P attie B lack C otton-, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

S cotland Neck City B oard oe E ducation, et al.

No. 70-188

P ecola A nnette W right, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Council of the City of E mporia, et al.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONS FOR

WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

N orman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. L eV onne Chambers

A dam Stein

237 West Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ames B. W alker, Jr.

501 West Third Street

Weldon, North Carolina 27890

Samuel S. M itchell

126% East Hargett Street

Raleigh, North Carolina 27601

Conrad O. P earson

203% E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

S. W. T ucker

H enry L. M arsh, III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Petitioners

I n th e

Supreme Qhmtl of % Itutpfc BUUb

October Term, 1971

No. 70-187

P attie B lack Cotton, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

S cotland Neck City B oard op E ducation, et al.

No. 70-188

P ecola A nnette W right, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

Council op the City op E mporia, et al.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONS FOR

WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Counsel for petitioners in each of these cases, presently

pending upon petitions for writs of certiorari, file this joint

Supplemental Brief pursuant to Rule 24(5) of this Court.

Significant decisions of federal and state courts have been

rendered since the filing of the petitions for writs of certio

rari, each of which underscores the importance and desir

ability of granting review in these cases.

The three pending matters referred to in footnote 10 at

page 17 of the petition in No. 70-188 have been decided.

In each instance, a rule contrary to that announced by the

2

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in

these cases has been applied, to reach results opposite to

those permitted by the decisions of which review is sought.

In Lee v. Macon Coimty Board of Education, No. 30154

(5th Cir. June 29, 1971) (reprinted as Appendix A, pp.

la-21a), the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit re

quired that a newly established separate city school dis

trict in Oxford, Alabama be treated, for purposes of relief

in the pending school desegregation case, as part of the

county system from which it was excised. The court ex

plicitly eschewed deciding the matter on the basis of sub

jective intent, but instead emphasized the effect upon de

segregation of the entire area if the new system had to be

treated as a separate entity:

The city cannot secede from the county where the

effect—to say nothing of the purpose—of the secession

has a substantial adverse effect on desegregation of

the county school district.(((la)

Prior to the re-creation of a separate city school district

in Oxford, white students from the county had crossed city

boundaries to attend white schools in Oxford while black

students from Oxford had attended the county training

school outside the City limits (3a)—just as was true of

Emporia and Greensville County (Petition in No. 70-188,

p. 64a) and Scotland Neck and Halifax County (Petition

in No. 70-187, p. 3). The Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit adopted a simple, clear and effective rule to ensure

that the constitutional rights sought to be enforced by

plaintiffs in school desegregation actions would not be

frustrated by mid-litigation creation o f , new entities; at

the same time, the Court of Appeals was solicitous of the

State’s interest in maintaining its control over its political

organization:

3

It is unnecessary to decide whether long established

and racially untainted boundaries may be disregarded

in dismantling school segregation. New boundaries can

not be drawn where they would result in less desegre

gation when formerly the lack of a boundary was in

strumental in promoting segregation. Cf. Henry v.

Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District, 5 Cir.

1969, 409 F.2d 683, 688, n. 10 [cert, denied, 396 U.S.

940 (1969)]. (lla-12a) (emphasis in original)

Similarly, in Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, Nos. 29886 and 30387 (5th Cir., July 16, 1971) (re

printed as Appendix B, pp. 22a-24a), another Fifth Circuit

panel, citing the Lee v. Macon County decision and this

Court’s ruling in North Carolina Stale Board of Education

v. Swann,----- U.S. ------- , 28 L.Ed.2d 588, 589 (1971), di

rected that newly formed school districts be ignored in the

development and implementation of an adequate desegre

gation plan on remand (24a):

Likewise, where the formulation of splinter school

districts, albeit validly created under state law, have

the effect2 of thwarting the implementation of a uni

tary school system, the district court may not, con

sistent with the teachings of Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg, supra, recognize their creation.3

2 The process of desegregation shall not be swayed by inno

cent action which results in prolonging an unconstitutional

dual school system. The existence of unconstitutional discrim

ination is not to be determined solely by intent. Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958); Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, 190 F. Supp. 861 (E.D. La. 1960), aff’d sub nom.,

City of New Orleans v. Bush, 333 U.S. 212 (1961) ; United

States v. Texas,------ F. Supp.------- , Part II (E.D. Tex. 1971),

aff’d as modified, United States v. Texas, —— F .2d ------ (5th

Cir., No. 71-1061, July 9, 1971).

3 See, Lee, et al. v. Macon County Board of Education,------

F .2 d ------ (5th Cir. 1971) [No. 30154, June 29, 1971, Part

II].

4

Jenkins v. Township of Morris School District, No. A-117

(Sup. Ct. N.J., June 25, 1971) (reprinted as Appendix C

pp. 25a-53a) dealt with the power of the State Commis

sioner of Education, in carrying out the federal and state

policies guaranteeing equal educational opportunity, to pro

hibit the withdrawal by a township of its high school stu

dents from the town educational system. The commissioner

found that creation of a separate township high school sys

tem and withdrawal of its students, largely white, from the

town high school, whose student body was becoming increas

ingly black, would have “adverse educational impact . . .

in the light of the growing racial imbalance between the

entire student populations of the town and the township”

but concluded that state law did not give him the power to

cross district lines. The Supreme Court of New Jersey re

jected that view and ordered the commissioner not only to

prevent withdrawal, but to consider merger on a 12-grade

basis, because of the effect which could be anticipated even

if separate elementary systems only were maintained:

The projections leave little room for doubt as to the

unfortunate future if suitable action is not taken in

timely fashion. The commissioner explicitly referred

to the growing racial imbalance between the town and

the township and to its long range harmful effects on

the school systems of both; and he recognized that un

less forestalled there would be another urban-sub

urban split between black and white students. (50a)

(emphasis supplied)

The New Jersey court emphasized (in connection with its

discussion of the vote against consolidation in a nonbind

ing township referendum) that intent was not the standard

upon which judgment was to be based:

It has been suggested that it was motivated by consti

tutionally impermissible racial opposition to merger

5

(cf. Lee v. Nyquist, supra, 318 F. Supp. 710; West Mor

ris Regional Board of Education v. Sills,------N. J .------

(1971)), but we pass that by since the commissioner

made no finding to that effect and his powers were, of

course, in no wise dependent on any such finding.

(53a) (emphasis supplied)

Petitioners submit that these rulings by another United

States Court of Appeals and a State Supreme Court apply

to the resolution of problems identical to those presented

in these two cases, standards which are directly contradic

tory to the standards announced by the Fourth Circuit.

These new rulings, however, are completely consonant with

the Eighth Circuit’s decision in the Burleson case, 432 F.2d

1356 (8th Cir. 1970), aff’g per curiam 308 F. Supp. 352

(E.D. Ark. 1970). The sharpened conflict of decision between

the Fourth, Fifth and Eighth Circuits compels resolution

by this Court.

Finally, petitioners noted (Petition in No. 70-188, p. 17)

that the device sanctioned below would prove an increas

ingly popular means of avoiding desegregation. The Fifth

Circuit suggested the same thing in Lee v, Macon County,

supra (f/~a):

If this were legally permissible, there could be incorpo

rated towns for every white neighborhood in every

city.

This is borne out by the experience in Jefferson County,

Alabama, where prior to the July 16 Stout decision, four

new white school districts had been excised from the county.

See the district court’s order on remand, reprinted as Ap

pendix D, pp. 54a-55a.

6

W herefore, petitioners respectfully pray that writs of

certiorari be granted and that the decisions below be re

versed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

N orman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. L eV onne Chambers

A dam S tein

237 West Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ames R. W alker, J r.

501 West Third Street

Weldon, North Carolina 27890

Samuel S. M itchell

126% East Hargett Street

Raleigh, North Carolina 27601

Conrad O. P earson

203% E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

S. W. T ucker

H enry L. Marsh, III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Petitioners

A P P E N D I C E S

Appendix A

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 3 0 1 5 4

ANTHONY T. LEE, et a!.,

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Piaintiff-Intervenor-Appellants,

NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, INC.,

Plalntiff-Intervenor,

■verasis

MACON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et a!.,

and

CALHOUN COUNTY SCHOOL SYSTEM,

Defendant-Appellee,

and

CITY OF OXFORD SCHOOL SYSTEM,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Alabama

(June 29, 1971)

la

2a

Before WISDOM, COLEMAN, and SIMPSON,

Circuit Judges.

WISDOM, Circuit Judge: This school desegrega

tion case5 involves the student assignment provisions

of the plan for desegregating the public schools in Cal

houn County, Alabama. The United States, plaintiff-in-

tervenor, appeals from that portion of the court’s order

which would have the effect of leaving approximately

45 percent of this small district’s Negro students in

two virtually all-black schools; pairing alternatives

would fully segregate both schools.2 We feel compelled

to reverse the district court on this issue.

I.

Calhoun County, in northeastern Alabama, has

a county school system serving rural areas and incor

porated municipalities not having their own separate

>A three-judge court consisting of Circuit Judge Richard T. Rives

and District Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. and H. H. Grooms

was convened in 1964 to hear a constitutional challenge to

an Alabama tuition grant law. See Lee et als v. Macon County

Board of Education, et als, M.D. Ala., 1964, 231 F. Supp. 743.

Ninety-nine local school systems, including Calhoun County’s

were involved in the suit. See Lee v. Macon County Board

of Education, 1967, 267 F. Supp. 458, aff’d sub nom. Wallace v.

United States, 1967, 389 U. S. 215. The court continued to sit

in the school desegregation cases. By its order of June 12,

1970, the three-judge court transferred this case to the Northern

District of Alabama under 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a). The matter

giving rise to the June 12 order was not “required” to be

heard by a three-judge court. The appeal therefore properly

lies to this court. 28 U.S.C. 1253, 1291.

zAlthough the exact figures are not available to show the result

of the district court’s order, approximately 730 black students

will be in the two all-black schools.

Appendix A

3a

systems. There are five school systems in the county,

the Calhoun County system and four city systems. In

1969-70, the county board operated 24 schools, of which

two were all-black and ten all-white. The system had

about 11,322 white and 1573 black students (12 percent).

Over 1000 of the blacks were in the two all-black

schools.3 At issue here is the assignment of the stu

dents in these two schools, the Calhoun County Train

ing School and the Thankful School. Necessarily in

volved in any desegregation plan are the formerly all-

white schools in Oxford and Mechanicsville School,

v/hich is in a rural area. These schools lie closest to.

the all-black schools and present the most feasible op

portunity for achieving desegregation by pairing.

Calhoun County Training School is located in all-

black Hobson City, an incorporated town on the edge

of Oxford City. Hobson City had a population of 770

in 1960; today it is thought to have double that popula

tion. County Training has served the black students

not only of Hobson City but also of Oxford and other

areas. Oxford Elementary School and Oxford High

School, located on a common site, have served whites

from Oxford and outlying areas. County Training and

the Oxford schools are 1.6 miles apart by road.

Because of the school district’s rural character and

the board’s previous maintenance of a segregated

school system, the county has provided extensive

Appendix A

sThere were more Negroes in all-black schools last year than under

the court’s order for this coming year. This is because some

of the black students at Calhoun County Training last year

were assigned to other schools under the board’s zoning plan.

4a

school bus transportation for students. Of the almost

13,000 students in the county system 10,000 or 77.6 per

cent were bussed to school in 1969-70. Approximately

the same percentage of students were bussed to the

Oxford schools as in the system as a whole. Some of

these students were picked up within the city boun

daries.

Past de jure segregation and residential patterns

have shaped the context of this case. In 1899' Hobson

City, which had been part of Oxford, was separately

incorporated after the area’s black residents were

gerrymandered out of Oxford, according to undisputed

testimony in the record. Custom continued the residen

tial segregation: Hobson City has remained all-black

and in Oxford blacks (five percent of the population)

live only in the section closest to the Oxford-Hobson

border.

Oxford had an independent school system until 1932

when its schools became part of the county system.

During this past school year, while the county system

was under court order to submit plans for county-wide

desegregation, Oxford established a city school system

under a City Board of Education. This board requested

the Calhoun County Board to transfer control of the

two Oxford schools to the new board. The takeover

became effective July 1, 1970. The city school board

has urged that its status as an independent entity is

relevant to desegregation proposals.

The other all-black school, Thankful School, is to the

north of County Training. Thankful served 278 black

Appendix A

5a

children in grades 1-6 in the 1969-70 school year. Thank

ful is approximately one mile from Mechanicsville

School, which has been serving 595 white children. Dur

ing the 1969-70 school year, 510 of these were bussed

to school. There are several other formerly all-white

county elementary schools within a radius of about

three miles of Thankful.

The issues in this case can best be considered by

describing the plans submitted to the three-judge court

by the various parties.

Under orders of the Court, the Calhoun County Board

of Education, January 12, 1970, submitted a plan pro

posing the closing of the two black schools,4 County

Training and Thankful, and distributing the students

from these schools among a number of the other coun

ty schools.5 The Oxford schools would have received

Appendix A

4The county had previously closed several black schools and assigned the pupils

to formerly white schools. This included the closing of grades 7-9 at Thank

ful.

sThe projection for the effect of the county’s plan is as follows:

Projected

Enrollment Formerly W

School Capacity Gr. W N T or N Schools

Calhoun Co. Training 1020 (closed) N

Thankful 450 (closed) N

Blue Mountain 180 1-6 151 29 180 W

Eulation 390-420 1-6 400 20 420 w

Mechanicsville 720 1-6 590 130 720 w

Saks El. 870-1010 1-6 950 62 1012 w

Saks High 1200 7-12 980 126 1106 w

Oxford El. 810-1035 1-6 820 250 1070 w

Oxford High 1840-1860* 7-12 1375 220 1595 w

Welborn 1380 7-12 1200 200 1400 w

*“On extended day school schedule”

6 a

a number of the black students from County Training.

The Oxford Board of Education, which asserts its sep

arate identity with respect to sending its students to

County Training, concurred in the plan. The school

closing plan would result in an extended day-school

schedule at Oxford High to house 1595 pupils in grades

7 to 12. While the plan indicated a capacity of 1840-1860

at Oxford High based upon the extended day sched

uling, the Building Information Form for that school

for the 1969-70 school year, stated that the maximum

capacity was 1230. The plan would assign 1070 children

to Oxford Elementary, with a regular capacity of 810,

1035 including 7 portable and 2 temporary rooms.

The plaintiffs and the United States objected to clos

ing Calhoun County and Thankful on the ground that

it was racially motivated and would impose an uncon

stitutional burden on the Negroes. The conclusion that

the proposed closing was racially motivated was based

on the fact that the facilities to be closed were physical

ly adequate and that the county board’s justifications

included the argument that whites would resist going

to school in facilities formerly used by blacks. As an

alternative, the plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenors sug

gested various pairing plans that would link County

Training with the Oxford Elementary and High

Schools, and link Thankful School with Mechanicsville

School.6 On February 10, 1970, the court ordered the

Appendix A

eSeveral pairing proposals were put forward. For County Train

ing and the Oxford schools, the plaintiffs at one point proposed,

without attendance projections, the following division: Oxford

Elementary 1-5; County Training 6-9, Oxford High 10-12. The

7a

system to show cause why this alternative should not

be implemented, noting that “ [t]he school system’s

plan appears to impose an unnecessary burden on the

children of both races solely to avoid assigning white

students to a formerly black school. The imposition

of such a burden, when based on racial factors, vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Appendix A

According to the county superintendent of schools,

the Thankful School, built in 1953, is “in good condi

tion,” has a “good” site and its “landscaping is fine” .

The Mechanicsville School, which would absorb more

than 100 students if Thankful were closed, is located

about one mile from Thankful. Its site is not as attrac

tive as the one at Thankful. A portion of the Calhoun

plaintiffs later put forward the following pairing plan with

projections:

Grades White Negro Total Capacity

Oxford Elementary 1-4 575 175 750 810

Oxford High 5-9 860 249 1109 1230

County Training 10-12 694 233 927 1020

Additionally, the United States proposed the following pairing

suggestion for these

Enrollment

School Gr. W N T

County Training 1-4 575 175 750

Oxford El. 5-8 625 175 800

Oxford High 9-12 1050 150 1200

There is some dispute as to the capacity of County Training.

County records, before the issue of pairing was raised, showed

it as 1020; countering the pairing proposals the county urged

that in fact the capacity was only 750.

As to the pairing of Thankful and Mechanicsville, no grade

structure was proposed by the parties. The following figures

were presented:

Mechanicsville

Capacity

720

Wh. N. Total

Thankful 360 610 260 870

8a

Appendix A

County Training School was built in 1945 and the re

mainder in the 1950’s and 1960’s. It might cost a mil

lion dollars to build a structure like Calhoun County

Training at present. The system does not presently

have available money for new construction. The court

stated in the terminal order of June 12, 1970, that Coun

ty Training had “an excellent physical plant. . . .”

The County System gave three reasons for opposing

the pairing. (1) Whites would flee from the public

schools.7 (2) It would be expensive to convert the

Training School to an elementary school. (3) Hobson

City’s two percent license tax, covering teachers,

would make it difficult to acquire suitable teachers.

The Oxford system opposed the pairing for a number

of reasons. (1) It agreed with the county board that

whites would flee the public schools.8 (2) Hobson City

is a separate town with its own government. (3) The

7The board stated: “These Defendants believe, and, if given an

oonortunity to do so, will undertake to present oral testimony

to show that if the Court adopts the proposed modification it

will bring about extensive efforts to operate private school

systems to accommodate any white students who might be

assigned to the facilities now housing Calhoun County Training

School. It would further be likely to bring about extensive re

location of families in an effort to avoid such assignment.

Adoption of the proposed alternative is certain to . . . create

avoidable new problems” .

sThe defendants strongly urge to the court that the closing of the

Oxford Elementary School would not effect a racial balance

and would do more toward resegregating the races according

to color than ever before; that the parents of children living

in Oxford would not send their young children unescorted into

an all colored municipality; that private schools have been

established and are being established in Oxford and Anniston

and their enrollments for the next school year have already

reached their capacity.

9a

Appendix A

Oxford System would not have elementary grades,

thereby making it difficult to attract industry. (4) Pair

ing would require bussing; some students live 3 or 4

miles from County Training; the Oxford system did

not intend to operate buses.

The county board then proposed a new plan that

would keep both County Training and Thankful open

for grades 1-6. Under this plan, student assignments

would be based on geographic attendance zones. Since

the zone boundaries followed historic neighborhood

boundaries, their projected effect was to make County

Training all-black and Thankful virtually so.9 Children

in grades 7 to 12 formerly attending these schools

would be distributed to the formerly white schools ac

cording to the original county proposal.

After a hearing the district court entered a single

order for the Calhoun County and Oxford systems ac

cepting the county board’s plan except for an amend

ment providing that the board operate County Training

for grades 1 to 12 instead of 1 to 6. The order stated

that “the evidence . .. reflects that [County Training]

sThe figures for the county board’s revised plan are as follows:

Enrollment

Gr. W N Capacity

Thankful 1-6 20 230 360

Mechanicsville 1-6 590 30 720

Blue Mountain 1-6 175 5 180

Saks El. 1-6 950 5 1012

Eulation 1-6 390 6 420

Oxford El. 1-7 960 95 1070

County Training 1-6 — 250 750

Children 7-12 grades in the Thankful zone would attend Saks

and Wellborn High schools, and those in the County Training

zone would attend Oxford High.

10a

is an excellent physical plant”. The effect of the order

is to continue the school’s all-black character serving

grades 1 to 12 and to deprive approximately 200 black

students of the integration provided by the county

plan.'0 Under the plan, approximately 45 percent of

the black students in the system will be assigned to

Thankful and County Training, 29.4 percent to all-black

County Training for their entire school careers.

II.

The first issue we discuss is whether Oxford’s seces

sion from the Calhoun County school system requires

that its schools be treated as an independent system.

Oxford asserts its freedom to keep its pupils in schools

within the city limits; the board had no objection to

receiving black students in its schools from outside

the city, as was proposed by the county in its original

plan. But the city’s claim to be treated as a separate

system has little merit. In its power as a court of equity

overseeing within this Circuit the implementation of

Brown v. Board of Education, 1955, 349 U.S. 294, 300,

this Court must overcome “a variety of obstacles in

making the transition to school systems operated in

accordance with the constitutional principles set forth

in (Brown I).” Brown II, supra.

Appendix A

toFigures are not available on the exact number of students that

County Training would have under the plan. The Oxford board

has submitted information showing that under the plan it

would have only 157 Negro students out of an enrollment of

2441 in grade 1-12.

11a

For purposes of relief, the district court treated the

Calhoun County and Oxford City systems as one. We

hold that the district court’s approach was fully within

its judicial discretion and was the proper way to handle

the problem raised by Oxford’s reinstitution of a sep

arate city school system. The City’s action removing

its schools from the county system took place while

the city schools, through the county board, were under

court order to establish a unitary school system. The

city cannot secede from the county where the effect

— to say nothing of the purpose — of the secession

has a substantial adverse effect on desegregation of

the county school district. If this were legally permis

sible, there could be incorporated towns for every

white neighborhood in every city. See Burleson v. Jack-

son County Board of Election Commissioners, E.D.

Ark. 1970, 308 F. Supp. 352 (proposed re-establishment

of a discontinued district); Wright v. Greenville Coun

ty Board, E.D. Va. 1970, 309 F. Supp. 671; United States

v. Halifax County Board of Education, E.D.N.C., May

23, 1970, C.A. No. 1128; Turner v. Warren County Board

of Education, E.D.N.C., May 23, 1970, C.A. No.

1482-RE. Even historically separate school districts,

where shown to be created as part of a state-wide dual

school system or to have cooperated together in the

maintenance of such a system, have been treated as

one for purposes of desegregation. See Haney v. County

Board of Education of Sevier County, 8 Cir. 1970, 410

F.2d 920; United States v. Crockett County Board of

Education, W.D, Term. May 15, 1967, C.A. 1663.

School district lines within a state are matters of

political convenience. It is unnecessary to decide

Appendix A

12a

whether long-established and racially untainted boun

daries may be disregarded in dismantling school seg

regation. New boundaries cannot be drawn where they

would result in less desegregation when formerly the

lack of a boundary was instrumental in promoting seg

regation. Cf. Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate

School District, 5 Cir. 1969, 409 F.2d 683, 688, n. 10.

Oxford in the past sent its black students to County

Training. It cannot by drawing new boundaries dis

sociate itself from that school or the county system.

The Oxford schools, under the court-adopted plan, sup

ported by the city, would serve an area beyond the

city limit of Oxford. Thus, the schools of Oxford would

continue to be an integral part of the county school

system. The students and schools of Oxford, there

fore, must be considered for the purpose of this case

as a part of the Calhoun County school system.

III.

The second question is whether the plan approved

by the district court is sufficient to satisfy the school

board’s affirmative duty to disestablish the dual sys

tem. A geographical zoning plan for student assign

ments will sometimes satisfy this duty, depending on

its practical effects and the feasible alternatives. But

it will not satisfy the board’s duty to dismantle the

dual system when it does not work. Henry v. Clarks

dale Municipal Separate School District. To be satis

factory, a zoning plan must effectively achieve deseg

regation. When historic residential segregation creates

housing patterns that militate against desegregation

Appendix A

13a

based on zoning, alternative methods must be ex

plored, including pairing of schools. See Green v. Coun

ty School Board, 1968, 391 U.S. 430, 442, n. 6. Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 1971,

U.S. , 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554.

An analysis of the plan adopted by the district court

shows that it does not satisfy the board’s obligation

to desegregate. While the plan does put some black

students in formerly all white schools, it leaves over

45 percent of the district’s Negro students in all-black

or virtually all-black schools. This continued segrega

tion results from extensive residential segregation and

boundary drawing to retain “the comfortable security

of the old, established discriminatory pattern.” Mon

roe v. Board of Commissioners of Jackson, 1968, 391

U.S. 20. For instance, the zone boundaries adopt the

dividing line between Oxford and Hobson, a boundary

tainted by racial gerrymandering.

The appellees contend with respect to County Train

ing that Hobson takes pride in its school and wants

it to continue as it has been. Although this seems a

misinterpretation of the testimony of Mayor Striplin

of Hobson,” even if it were accurate it would not sup-

*'Mayor Striplin seemed from the record to be saying only that if

the schools were not to be paired the black community would

prefer to have the facility used by 12 grades than have it

partially abandoned, But there was other language that would

support an interpretation that the community desired to have

a twelve grade all-black school. In a letter dated January 7,

1970, addressed to the Director of the Health, Education, and

Welfare Department, Mayor Striplin wrote, in part:

“ it would bring hardship to this 1,500 populated com

munity to be without a school. We are not trying to

Appendix A

14a

port a defective plan. The district court should require

the School Board forthwith to constitute and implement

a student assignment plan that complies with the prin

ciples established in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education.

Appendix A

IV.

The county board’s original plan proposed to close

the formerly black schools and disperse the students

among formerly white schools. Although this plan

would bring about student body desegregation, plain

tiffs objected that the plan was unconstitutional be

cause the closing of the two schools was racially mo

tivated and placed an unequal burden on Negro stu

dents.

Closing schools for racial reasons would be unconsti

tutional. The equal protection clause of the fourteenth

amendment prevents any invidious discrimination on

the basis of race. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 1886, 118 U.S.

356. A governmental unit bears a “very heavy burden

of justification” to support any use of racial distinc

tions. Loving v. Virginia, 1967, 388 U.S. 1, 9. Under

general equal protection doctrine, therefore, it would

be impermissible for the school board to close formerly

black schools for racial reasons. More particularly,

such action is prohibited by the school desegregation

buck the guide lines, we are only asking you to spare

our school in some way. f We have Whites living all

around us. Some in walking distance, some on the bus

lines, can they be brought in? They are welcome. . . .”

15a

A ppendix A

cases. Brown II, supra, calling for “a racially non-

diseriminatory school system,” and its progeny re

quire not only that past discriminatory practices be

overcome by affirmative actions but also that new

forms of discrimination not be set up in their place.

Closing formerly black school facilities for racial rea

sons would be such a prohibited form of discrimina

tion. “Such a plan places the burden of desegregation

upon one racial group.” ’2 Brice v. Landis, N.D. Cal.

1969, 314 F. Supp. 947. See Quarles v. Oxford Municipal

Separate School District, N.D. Miss. January 7, 1970,

C.A. W.C. 6962-K.

We are frankly told in the County Board’s brief that

without this action it is apprehended that white stu

dents will flee the school system altogether. “But it

should go without saying that the vitality of these con

stitutional principles canot be allowed to yield simply

because of disagreement with them.” Brown II, at 300.

See Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of Jackson,

at 459.

i^In Brice v. Landis, N.D. Cal., August 8, 1969, No. 51805, the court

discussed the discriminatory closing of formerly black schools:

“The minority children are placed in the position of

what may be described as second-class pupils. White

pupils, realizing that they are permitted to attend

their own neighborhood schools as usual, may come to

regard themselves as ‘natives’ and to resent the negro

children bussed into the white schools every school

day as intruding ‘foreigners.’ It is in this respect that

such a plan, when not reasonably required under the

circumstances, becomes substantially discriminating

in itself. This undesirable result will not be nearly

so likely if the white children themselves realize that

some of their number are also required to play the

same role at negro neighborhood schools.”

16a

In Gordon v. Jefferson Davis Parish School Board.,

5 Cir. July , 1971, F.2d [No. 30,075], this

Court, relying on Quarles, Brice, and Haney v. County

Board of Education of Sevier County, 8 Cir. 1970, 429

F.2d 364, recently remanded the case to the district

court with directions that the court “promptly conduct

hearings, and thereon makes findings and conclusions

as to whether or not the closing [of two schools] v/as

in fact racially motivated”. Here, however, it is clear

from the record and briefs that the primary reason

for closing the schools was the county board’s conclu

sion that the use of the black facilities would lead

whites to withdraw from the public system. And there

is little evidence of any legitimate reasons for the clos

ings. Although arguing below that the black facilities

were inferior, appellees asserted on appeal that the

facilities of County Training “are excellent.” Also, the

district court found County Training to have an “ex

cellent physical plant” in assigning twelve grades of

black students there. Thus the action is not supported

by the inferiority of the physical facilities. Moreover,

the county’s plan would have required an extended

day at Oxford High because of the crowding caused

by closing County Training. On the record before us,

the county’s original proposal is unacceptable.

V.

In contrast to the defects of the plan adopted by the

court and the county’s original plan to close County

Training and Thankful Schools, the school system

seems suitable for pairing several schools to achieve

desegregakn. County Training and the Oxford Ele

Appendix A

17a

mentary and High School complex are only 1.6 miles

apart by road. Thankful and Mechanicsville are only

one mile apart. These figures compare favorably with

distances between elementary schools this court has

ordered paired in the past. See, e.g., Bradley v. Public

Instruction of Pinellas County, 5 Cir. July 28, 1970 (ele

mentary schools one and two miles apart paired).

In addition, a great number of the students attend

ing these schools in the past have been transported

to school by the county school bus system. In its orig

inal proposal the county planned to provide the neces

sary transportation for the black students to be dis

persed to the formerly white schools, demonstrating

the ability of the county to use its transportation sys

tem to accomplish desegregation. The bussing neces

sary to handle the pairing might involve a moderate

increase over that provided by the County in the past.

Where transportation facilities exist, a requirement of

a moderate increase in transportation is a proper tool

in the elimination of the dual system. Tillman, Jr. v.

Volusia County, 5 Cir. July 21, 1970, F.2d [No.

, July 21, 1970],

The appellees overstate the case as to the alleged

difficulties in pairing. The first assertion is that physi

cal barriers exist between County Training and the

Oxford School complex, i.e. railroad tracks and high

ways. But a view of the maps of Oxford and Hobson

show that these barriers not only separate the two

schools but also separate a large number of white stu

dents from the Oxford school complex. The result is

that some white students live on the County Training

Appendix A

18a

side of the tracks and highways, and therefore crossed

these to attend the Oxford schools. Barriers that in

the past have yielded to segregation should not now

prevent pairing to achieve integration. Also, the dif

ficulty of physical barriers is decreased by the avail

ability of transportation.

The appellees also assert that the road that school

busses must use in traveling to County Training is un

safe for such buses. Considering that this road has

been used by school busses going to County Training

in the past in order to maintain segregation, such dif

ficulties cannot now be found insurmountable.

The City of Oxford argues that pairing cannot pro

ceed on the assumption that pupils will be transported.

In the past it has been the practice of the county school

system not to transport children living within a sep

arate municipal school district to schools run by the

municipality. But application of the rule to the situa

tion involved here is predicated on the idea that Oxford

has become a separate school district. Since we have

concluded that for purposes of this case the Oxford

schools should not be considered a separate entity, the

county must continue to treat Oxford as an integral

part of the county system for purposes of providing

school bus transportation. Last school year the county

did provide transportation to Oxford Elementary and

High Schools for some students living within the Oxford

city limits. The county board must now reconstitute

its transportation system to provide transportation

necessary for the pairing ordered by this decision.

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

Appendix A

Appendix A

trict, 5 Cir. 1969, 419 F.2d 1211, 1217, n. 1 (en banc),

rev’d other grounds, sub nom. Carter v. West Feliciana

Parish School Board, 1970, 396 U.S. 290, 90 S.Ct. 24

L.Ed.2d 477.

The appellees also argue that none of the pairing

proposals suggested by the plaintiffs are practicable

because the capacity of County Training is too small

to accommodate the number of pupils that would be

assigned to it under them. We note that until the ques

tion of pairing arose the official records of the county

system showed County Training’s capacity to be 1020,

as opposed to the 750 now said to be its capacity. Even

if the capacity is 750, pairing is feasible. See the pro

posal by the United States, note 6 supra.

We do not prescribe the grade structure to be used

in pairing these tw7o sets of schools. The county system

(including the Oxford City board), after consulting

with the plaintiffs and the plaintiff-intervenors, should

assign grades to these schools for the 1970-71 school

year, using each school to the same fraction of its ca

pacity as far as practical.

The judgment of the district court as it relates to

student assignment is vacated and the cause is

remanded with directions that the district court re

quire the School Board forwith to institute and imple

ment a student assignment plan that complies with

the principles established in Swann v. Charlotte-Meck

lenburg Board of Education and reflects any changes

in conditions relating to school desegregation in Cal

houn County since the Court’s decree of June 12, 1970.

20a

The district court shall require the School Board to

file semi-annual reports during the school year simi

lar to those required in United States v. Hinds County

School Board, 5 Cir. 1970, 433 F.2d 611, 618-19.’3

VACATED AND REMANDED WITH DIRECTIONS.

The Clerk is directed to issue the mandate forthwith.

COLEMAN, Circuit Judge, concurring in part and

dissenting in part.

I regret that I cannot fully agree with the majority

opinion in this case. Of course, I agree that all reason

able means must be exercised to dismantle dual school

systems and to establish unitary ones. My disagree

ments, now and in the past, have been founded upon

my opposition to unrealistic plans, doomed to failure

from the beginning, whereas a discretionary approach

by the District Judge would more likely have been

crowned with better results, rather than destroying

public schools, so badly needed by white and black

alike.

Admittedly the problem in Calhoun County, Ala

bama, is not acute. There appears to be no real ob

stacle to the speedy accomplishment of a unitary

school system in this area.

Appendix A

’ a This decision is based on a state record, in part because this Court

(en banc) determined to withhold all decisions in school

desegregation cases pending the Supreme Court’s issuance of

its judgment in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

21a

I agree that school systems in the process of deseg

regation may not escape their obligations by changing

their operational status, as Oxford has attempted to

do.

From such knowledge of history as I have I am not

convinced, that the incorporation of Hobson City in

1899, when Plessy v. Ferguson was on the books, had

any racial connotations, unless it may have been that

the black citizens desired a municipality of their own,

as, for instance, Mound Bayou, Mississippi.

For the reasons stated in my dissenting opinion in

Marcus Gordon v. Jefferson Davis School Board [No.

30,075, slip opinion dated _____________________, 1971]

------F.2d------- , I disagree with Part IV of the majority

opinion. As I said there, race is, of necessity, at the

bottom of all school desegregation orders; otherwise

there would be no Fourteenth Amendment jurisdiction.

I shall not repeat here that which I have already put

of record in Gordon. I simply adhere to the point.

I shall only add a reference to what the Supreme

Court said in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education:

“Just as the race of the students must be

considered in determining whether a violation

has occurred, so also must race be considered

in formulating a remedy”. [39 U.S.L.W. at

4449],

Appendix A

Appendix 8

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOE THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 2 9 8 8 6 *

N o . 3 0 3 8 7

LINDA STOUT, by her father and

next friend, BLEVIM STOUT,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervener,

•versus

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellees,

BOARD OF EDUCATION FOR THE

CITY OF PLEASANT GROVE,

Defendant-Intervenor.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Alabama

(July 16, 1971)

Before THORNBERRY, CLARK and INGRAHAM,

Circuit Judges.

*No. 29886 is included in this order because of the inter-relation of

the issues raised therein and in order that the district court

on remand will have the opportunity to assure compliance

with the uniform provisions relating to faculty and other staff

22a

23a

BY THE COURT: The order of the district court

under review is vacated and the cause is remanded

with direction that the district court require the school

board5 forthwith to implement a student assignment

plan for the 1971-72 school term which complies with

the principles established in Swann v. Charlotte-Meek-

lenburg Board of Education, _ _ U.S. ____ 91 S.Ct.

1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554 (1971), insofar as it relates to the

issues in this case, and which encompasses the entire

Jefferson County School District as it stood at the time

of the original filing of this desegregation suit.

In North Carolina State Board of Education v.

Swann, __ _ U .S.____ , 28 L.Ed. 2d 588, 589 (1971), the

Supreme Court said:

". . . [I]f a state-imposed l i m i t a t i o n on

a school authority’s discretion operates to in

hibit or obstruct the operation of a unitary

school system or impede the disestablishing of

a dual school system, it must fall; state policy

must give way when it operates to hinder vin

dication of federal constitutional guarantees.”

Likewise, where the formulation of splinter school dis

tricts, albeit validly created under state law, have the

Appendix B

in Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

419 F.2d 1211; Id. 425 F.2d 1211.

’The district court shall include within its order a direction to

any school boards created since the filing of the original action

in this cause to submit to the plan to be approved by the dis

trict court.

Appendix B

effect2 of thwarting the implementation of a unitary

school system, the district court may not, consistent

with the teachings of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg,

supra, recognize their creation.3

The district court is also directed to implement fully

the uniform provisions of our decision in Singleton v.

Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 419 F.2d

1211; Id. 425 F.2d 1211, insofar as said uniform provi

sions relate to desegregation of faculty and other staff,

majority to minority transfer policy, transportation,

school construction and site selection, and attendance

outside system of residence. See also Carter v. West

Feliciana Parish School Board, 432 F.2d 875 (5th Cir.,

1970).

The district court shall require the school board to

file semi-annual reports during the school year simi

lar to those required in United States v. Hinds County

School Board, 433 F,2d 611, 618-19 (5th Cir., 1970).

The mandate shall issue forthwith.

VACATED and REMANDED with directions.

2The process of desegregation shall not be swayed by innocent ac

tion which results in prolonging an unconstitutional dual school

system. The existence of unconstitutional discrimination is not

to be determined solely by intent. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S.

1 (1958); Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 190 F.Supp.

881 (E.D. La., 1960); aff’d sub nom, City of New Orleans v.

Bush, 333 U.S. 212 (1961); United States v. Texas,_____F.Supp.

--------, Part II (E.D.Tex., 1971); aff’d as modified, United States

v. Texas, _____ F.2d _____ (5th Cir., No. 71-1061, July 9,

1971).

sSee, Lee, et al., v. Macon County Board of Education, _____ F.2d

-------- (5th Cir., 1971) [No. 30154, June 29, 1971, Part II],

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts—Scofields’ Quality Printers, Inc., N. O., La.

25a

SUPREME COURT OF NEW JERSEY

No. A-117—September Term 1970

Appendix C

B eatrice M. J e n k in s , et al.,

Y.

Petitioners-Appellants,

T h e T o w n sh ip op M orris S chool D istrict

and B oakd oe E ducation ,

Defendant-Respondent,

and

T h e T ow n oe M obbistow' n S chool and

B oard oe E ducation,

Defendant and

Cross-Petitioner-Appellant,

and

T h e B orough of M obbis P lain s B oard of E ducation ,

Defendant.

Argued April 6 and 26, 1971. Decided June 25, 1971.

On certification to the Appellate Division.

Mr. Frank F. Harding and Mr. Stephen B. Wiley argued

the cause for the appellants (Messrs. MacKenzie & Hard

ing, attorneys for the appellants Beatrice M. Jenkins, et al.;

Mr. Stephen B. Wiley, attorney for the appellant Morris

town Board of Education; Mr. Donald M. Malehorn and

Mr. Frank F. Harding, on the brief).

26a

Mr. Victor H. Miles argued the cause for the respondent.

Mr. Paul Bangiola argued the cause for the defendant

Borough of Morris Plains Board of Education.

The opinion of the Court was delivered by Jacobs, J.

The appellants sought to have the Commissioner of

Education take suitable steps towards preventing Morris

Township from withdrawing its students from Morristown

High School and towards effectuating a merger of the

Morris Township and Morristown school systems. The

Commissioner was of the opinion that, even though such

steps were highly desirable from an educational standpoint

and to avoid racial imbalance, he lacked legal authority to

take them and accordingly he dismissed the individual ap

pellants’ petition and the appellant Morristown’s cross

petition. The appellants filed notice of appeal to the Ap

pellate Division and we certified before argument there.

58 N.J. 1 (1971).

Prior to 1865 Morristown and Morris Township were a

single municipal unit. In that year Morristown received

permission to incorporate as a separate entity and arbitrary

boundary lines were drawn between the Township (Morris)

and the Town (Morristown). Despite their official separa

tion, the Town and the Township have remained so inter

related that they may realistically be viewed as a single

community, probably a unique one in our State. The Town

is a compact urban municipality of 2.9 square miles and is

completely encircled by the Township of 15.7 square miles.

The boundary lines between the Town and the Township

do not adhere to any natural or physical features but cut

indiscriminately across streets and neighborhoods. All of

the main roads radiate into the Township from the Green

located in the center of the Town and it is impracticable to

Appendix C

27a

go from most Township areas to other Township areas

without going through the Town itself.

The Town is the social and commercial center of the

community whereas the Township is primarily residential

with considerable undeveloped area for further residential

development. The Town has many retail stores and other

commercial establishments surrounding* its Green while the

Township has only a few retail outlets located on its main

roads. The Township has no business center or so-called

“downtown” area hut the Town’s substantial shopping cen

ter serves in that aspect for both the Township and the

Town. Most of the associations, clubs, social services and

welfare organizations serving the residents of both the

Town and the Township are located within the Town and,

as members of the aforementioned organizations, the Town

and Township residents are routinely together at both work

and play. The Morristown Green is a common meeting

place for young people from both the Town and the Town

ship; day care centers and park and playground facilities

in the Town are used by the residents of both the Town and

the Township; and little leagues and the like generally in

volve Town and Township teammates who play on both

Town and Township fields.

There is also considerable interdependency in municipal

public services. Thus the Town’s Water Department sup

plies water to most of the Township residents; sewer ser

vice is rendered by the Town to some parts of the Town

ship; Town and Township Fire and Police Departments

regularly assist each other; and the Town and Township

jointly operate the Public Library located within the Town.

There are socio-economic and population differences be

tween the Town and the Township but despite these dif

ferences the record before us clearly establishes that, as set

Appendix G

28a

forth in the Candeub report, the Town and Township “are

integrally and uniquely related to one another” and “con

stitute a single community.” The Candeub report was pre

pared for the Town by an established consulting community

planning firm. The hearing examiner, whose findings were

adopted and incorporated by the Commissioner of Educa

tion in his decision, found that the Morristown-Morris com

munity was essentially as described in the Candeub report;

he noted further that the Township did “not dispute the

interrelatedness between itself and the Town” though it

contended that statutorily and technically the Town and

Township are “separate entities for school purposes.”

The Township has a population of about 20,000 including

less than 5% blacks. The Town has a population of almost

18,000 including about 25% blacks. There was testimony

that within this decade the Town’s population of blacks

would probably increase to between 44% and 48%. Because

of employment considerations and other economic factors,

black families generally locate in the Town rather than the

Township. Town sales of single family homes average be

tween $22,000 and $24,000 whereas the homes in the Town

ship average between $40,000 and $60,000. Though the

Town’s school population is leveling off, its black school

population is increasing steadily. As of 1969 when the hear

ings were held below, the Town’s school enrollment was

2,823 and is not expected to exceed 3,200 by 1980 though

its black school population is expected to increase from

39% to over 65% by that time. Its elementary schools are

43% black but are expected to be 70% black by 1980. On

the other hand, the Township’s public school enrollment of

4,172 will probably reach 6,700 by 1980 and is expected to

remain overwhelmingly white. About 5% of the Township

students are black and there was testimony that this per

centage is likely to decrease rather than increase by 1980.

Appendix C

29a

Most of the Town and Township schools are located near

the Town boundary line and the hearing examiner made

pointed references and findings to their gross disparities

in racial composition. Thus he noted that the Town’s

Thomas Jefferson School with its 48% black enrollment

was “very close to the Township’s Woodland School with

zero percent black enrollment” ; that “geographic proximity”

also invited attention to George Washington School (Town,

45%) and Normandy Park School (Township, 9%) and to

Lafayette Junior High School (Town, 42%) and Alfred

Yail School (Township, 10%); and he pointed out that the

Alexander Hamilton School (Town, 35%) was “equidistant”

between Sussex Avenue School (Township, 5%) and Hill-

crest School (Township, less than 1%).

So far as Morristown High School is concerned, the

present black student population is about 14%. But its

student body now includes residents of Morris Township

and the neighboring municipalities, Borough of Morris

Plains and Harding Township. The projections introduced

by the Town indicate that if the Morris Township students

are withdrawn, the percentage of blacks in Morristown

High School will double immediately, and will probably

reach 35% by 1980; they indicate further that if the Morris

Plains and Harding students are also withdrawn the black

enrollment at Morristown High School will probably reach

56% by 1980. The hearing examiner accepted the Town’s

projections since they appeared to him “essentially reason

able” and no “real projections in contradiction” had been

offered.

For over a hundred years the Town and Township have

had a sending-receiving relationship under which the Town

ship sends Township students to Morristown High School.

There was a short interruption which continued only

Appendix G

30a

through 1958 and 1959. As of 1962 the Town and Township

executed a formal 10-year sending-receiving contract and

the Township has since been regularly sending its 10th,

11th, and 12th grade students to Morristown High School.

The contract contains a provision to the effect that after the

ten-year term the parties shall be free to make whatever

arrangements they mutually agree upon “subject to the

provisions of law and the approval of the Commissioner of

Education.” Incidentally, the residents of Morris Plains

and Harding now at Morristown High School include grade

9' through 12 students who attend under designation with

out formal contract.*

Morristown High School is an excellent educational in

stitution and offers diversified and comprehensive courses

of instruction including seven full vocational programs

and an equal number of advanced college placement courses

in English, social studies, science and language. It has a

total of 150 courses in contrast to the State median of 80-89

courses. It operates with an eight-period day, staggering

arrival and departure times. It accommodates 1950 students

and by using a nine-period day can accommodate 2450 stu

dents ; it is anticipated that the High School population will

not reach this latter figure until 1974. If the Township is

permitted to withdraw its students, Morristown High School

will have remaining about 1300 students as of 1974 and if,

* Harding Township was originally a party to the proceedings

but was permitted to withdraw by consent. Before the Commis

sioner, the Borough of Morris Plains sought a regionalization of

schools at the high school level and joined in the request to prevent

the withdrawal of Morris Township students from Morristown

High School. The Borough took no appeal from the Commissioner’s

determination and before us its counsel simply filed a statement in

lieu of brief which joined in the relief sought by the appellants

“ except that his demands for regionalization would be that of a

limited public regional high school for grades nine through twelve.”

Appendix C

31a

in addition, Morris Plains and Harding are permitted to

change their designation, the High School will then have

only about 800 students. The hearing examiner found that

“ to be left with only Harding and Morris Plains—and

especially to be left alone—would impose the following

disadvantages:

“1. By dint of reduced size alone Morristown High

School could not continue to provide the same scope

and variety of courses.

2. Withdrawal of Township students would mean with

drawal of a significant number of educationally

highly-motivated, capable students, and this is

likely to have an adverse affect upon the perform

ance and motivation of the remaining Town stu

dents.

3. The remaining students would be, as a group, from

lower socio-economic backgrounds and be less

oriented toward academic achievement, with the

result that the program structure will have to be

drastically re-oriented.

4. The percentage of black students in the High School

will be approximately as stated above: with Hard

ing and Morris Plains, 27% in 1974 and 35% in

1980; without Harding and Morris Plains, 44% in

1974 and 56% in 1980.

5. Morristown High School will not be able to main

tain its place in the scale of excellence in terms of

breadth and quality of program.

6. It is probable that, as a consequence, it will have

more difficulty in keeping and attracting the same

high quality faculty.

' Appendix C

32a

7. With the change in program and reputation and

the loss in tuition revenue, it is possible that the

Town will not be as able or as willing to support

financially its school system as it currently is.

8 . The Township students will be denied the privilege

of an integrated education.

9. The sudden alteration in the racial composition of

the High School might aggravate the tendency of

potential white buyers to avoid purchasing houses

in Morristown.”

On the issue of total K-12 merger between the Town and

Township, the examiner received considerable testimony

during the hearings before him. In the main it most per

suasively supported the high educational desirability and

economic feasibility of such a merger. The examiner, after

pointing to the sharp contrast between the Town’s K-12

black enrollment of 39% (projected to over 65% by 1980)

and the Township’s white enrollment of 95%, stressed that

“the close proximity of the Town and Township elementary

schools makes the disparity easily visible to and easily felt

by the students of the two districts” and that “the commu

nity with which Morristown residents, including students,

identify extends beyond the bounds of the Town and en

compasses the Township.” He firmly set forth his view

that if there is a failure to merge “the black student popu

lation of Morristown—particularly at the elementary school

level—will suffer the same harmful effects that the Commis

sioner of Education has worked so hard to eliminate within

single school districts throughout the State.” And though

he did not deal with it in explicit terms there is little doubt

that he subscribed to the Town’s testimony as to the ad

vantages of total merger, set forth as follows in the report

Appendix C

33a

submitted to the Town by the Engelhardt educational con

sulting firm and introduced in evidence at the hearings

below:

“The advantages to both Morristown and to Morris

Township of a K-12 merger may be summarized this

way:

1. Establishment of a racial balance which represents

the racial composition of the community. Bi-racial

experience will be available in the early grades

where it has important benefits for both white and

Negro students in terms of interracial attitudes

and preferences and at the later years where it

appears to have important benefits to members of

minority groups.

2 . Representation of the socio-economic spectrum of

the community at all levels of schooling.

3. Equal educational opportunity available to all stu

dents without regard to background, race, or resi

dence.

4. Avoidance of invidious comparison between the

Morristown High School and a Township school, a

comparison ultimately based on race.

5. Avoidance of the deterioration and pejoration of

Morristown High School because of racial con

centration, loss of reputation, curtailment of pro

gram, and ultimate reduction in per-pupil expendi

ture.

6 . Development of a district which represents a

natural community and avoidance of the creation

and perpetuation of racial imbalance.

Appendix C

34a

7. Development of a climate of education which, repre

sents the society in which the students live.

8. Development of a school district and a high school

large enough to allow the maximum return on the

funds invested and to permit a program broad

enough to meet a wide range of pupil needs.

9. Development of an educational pattern related to

and serving the single Morristown-Township com

munity.

10 . Deduction in the number of school districts in the

area from four to three.

11. Development of greater vertical coordination of

program and greater flexibility in facilities, cur

riculum, and organization.”

In January 1968 the Township Board of Education con

ducted a non-binding referendum among the Morris Town

ship residents. The voters were asked whether they favored

a separate K-12 school system for Morris Township or a

K-12 merger with Morristown. The vote was 2164 to 1899

in favor of a separate K-12 system. The examiner found

that prior to the vote six of the eight members of the Town

ship Board of Education had been on record in favor of some

sort of merger; that Board members agreed beforehand to

be bound by the results of the referendum; that since the

referendum the Board has conducted itself as if the decision

were irrevocably made to have a separate school system

including a separate high school; and that the Board de

clined to participate “in a study of regionalization with the

other school districts upon the invitation of the County

Appendix C

35a

Superintendent of Schools in accordance with the Com

missioner’s urgent recommendation.”

Following the referendum the Township Board of Educa

tion set upon a program for the construction of a separate

Township high school for Township residents in lieu of

the Morristown High School. A bond referendum in con

nection with the proposed construction wras scheduled but

was restrained, originally by the Commissioner of Educa

tion and later by this Court. In this proceeding the Town

ship Board has pressed for vacation of the restraint and

has apparently concentrated all of its efforts towards the

building of a new high school in pursuance of the vote at

the non-binding referendum. In his decision the Commis

sioner was highly critical of that referendum and the

Board’s conduct in connection therewith. Citing Hackensack

Bd. of Education v. Hackensack, 63 N.J. Super. 560 (App.

Div. 1960), and Botkin v. Westwood, 52 N.J. Super. 416

(App.Div.), appeal dismissed, 28 N.J. 218 (1958), he de

scribed the non-binding referendum as “illegal and an im

proper abdication of the Township Board’s responsibility

to perform its function.” And he flatly condemned the pre

vote “pledge of all but one” of the Board members to abide

by the results of the non-binding referendum, noting that

it “improperly delegates the responsibility for ultimate

decision.”

The Commissioner was also critical of the Township

Board’s refusal, since the vote, to consider any alternative

to a new high school and its failure to participate in the

regionalization study which he had urgently recommended.

He expressed his particular concern with “the adverse edu

cational impact of the proposed withdrawal of the Morris

Township students from Morristown High School” and

with “the long-range harmful effects to the two school sys-

Appendix C

36a

terns” in the light of “the growing racial imbalance between

the entire student populations of the Town and the Town

ship.” And he further expressed his desire to act, within

his powers, “so as to forestall the development of what may

be another urban-suburban split between black and white

students.” But having* pointedly made that clear, he then

proceeded to determine that he had no power, either to pro

hibit the withdrawal of Township students from Morris

town High School, or to direct any steps on the part of the

respective Boards towards merger of their school systems,

or to grant any other relief towards avoidance of the bane

ful effects he so soundly envisions. Accordingly he lifted

the restraint he had originally granted and dismissed the

petition and cross-petition which had been duly filed by the

appellants now before us.

The Commissioner’s flat disavowal of power despite the

compelling circumstances may be sharply contrasted with

the sweep of our pertinent constitutional and statutory

provisions and the tenor of our earlier judicial holdings.

See N.J. Const., art. 1, para. 5; art. 8, sec. 4, para. 1 (1947);

N.J.S.A. 18A.-4-23, 24; N.J.S.A. 18A:6-9; Bd. of Ed. of

Elisabeth v. City Coun. of Elisabeth, 55 N.J. 501 (1970);

Bd. of Ed., E. Brunswick Tp. v. Tp. Council, E. Brunswick,

48 N.J. 94 (1966); Booker v. Board of Education, Plain-

field, 45 N.J. 161 (1965); Morean v. Bd. of Ed. of Mont

clair, 42 N.J. 237 (1964); see also In re Masiello, 25 N.J.

590 (1958); Laba v. Newark Board of Education, 23 N.J.

364 (1957); Schults v. Bd. of Ed. of Teaneck, 86 N.J. Super.

29 (App.Div. 1964), aff’d, 45 N.J. 2 (1965).

Our Constitution contains an explicit mandate for legis

lative “maintenance and support of a thorough and effi

cient system of free public schools.” Art. 8, sec. 4, para. 1.

In fulfillment of the mandate the Legislature has adopted

Appendix C

37a

comprehensive enactments which, inter alia, delegate the

“general supervision and control of public education” in

the State to the State Board of Education in the Depart

ment of Education. N.J.S.A. 18A:4-10. As the chief ex

ecutive and administrative officer of the Department, the

State Commissioner of Education is vested with broad

powers including the “supervision of all schools of the

state receiving support or aid from, state appropriations”

and the enforcement of “all rules prescribed by the state

board.” N.J.8.A. 18A:4-23. The Commissioner is author

ized to “inquire into and ascertain the thoroughness and

efficiency of operation of any of the schools of the public

school system of the state” (N.J.8.A. 18A:4-24), is di

rected to instruct county superintendents and superin

tendents of schools as to “the performance of their duties,

the conduct of the schools and the construction and fur

nishing of schoolhouses” (N.J.8.A. 18A:4-29), and is em

powered to hear and determine “all controversies and dis

putes” arising under the school laws or under the rules

of the State Board or the Commissioner. N.J.8.A. 18A:6-9.

We have from time to time been called upon to reaffirm

the breadth of the Commissioner’s powers under the State

Constitution and the implementing legislation. Thus in

Laba, supra, 23 N.J. 364, we held that the Commissioner’s

“primary responsibility is to make certain that the terms

and policies of the School Laws are being faithfully ef

fectuated” (23 N.J. at 382) and he is empowered to remand

controversies and disputes “for further inquiry” at the

local board level when such course appears appropriate.

23 N.J. at 383. In Masiello, supra, 25 N.J. 590, we rejected

a narrow interpretation by the Commissioner as to his

powers on review of determinations by the State Board of

Examiners and held that his responsibilities entailed in

Appendix C

38a

dependent factual findings and independent interpreta

tions of State Board rules. 25 N.J. at 606-07.

In East Brunswick, supra, 48 N.J. 94, the voters twice

rejected the Township Board of Education’s school budget

and the Township Council thereupon cut the budget. The

Board filed a petition with the Commissioner of Educa

tion and we were asked to decide whether the Commis

sioner had power to determine the controversy between

the Board and the Council and power to order restoration

of the cut in the budget. We found that he did, pointing

out that since as early as 1846 the Legislature had charged

the State Commissioner with the duty of obtaining faith

ful execution of the school laws and that at no time had

his “comprehensive statutory responsibility” for deciding

all controversies or disputes under the school laws or the

State Board’s regulations ever been “withdrawn or nar

rowed.” 48 N.J. at 101. Referring to the constitutional

mandate for the maintenance and support of a thorough

and efficient school system (art. 8 , sec. 4, para. 1), we

noted that the Legislature had directed the local school

districts to provide “ suitable school facilities and accom

modations” (R.S. 18:11-1; N.J.8.A. 18A:33-1, 2 ) and had

vested the State supervisory agencies “with far reaching

powers and duties designed to insure that the facilities

and accommodations are being provided and that the con

stitutional mandate is being discharged.” 48 N.J. at 103-04.

We held that where the Commissioner finds that the budget

fixed by the local governing body is insufficient to satisfy

educational requirements and standards he should direct

local corrective action or fix the budget “on his own.”

48 N.J. at 107. See also Bd. of Ed. of Elizabeth v. City

Coun. of Elisabeth, supra, 55 N.J. 501.

The history and vigor of our State’s policy in favor of

a thorough and efficient public school system are matched

Appendix C

Appendix C