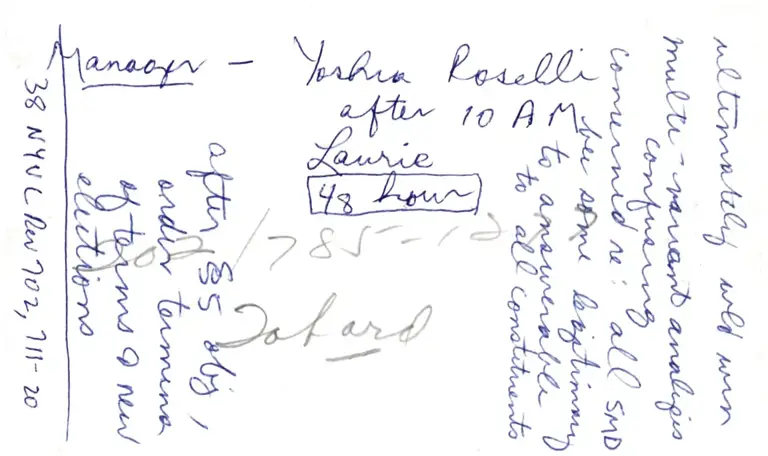

Attorney Notes, Memorandum from Moulton to Guinier

Working File

January 1, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Attorney Notes, Memorandum from Moulton to Guinier, 1984. 5bae4df8-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/77400f05-a33c-4a27-aa4c-f3bb37c6c581/attorney-notes-memorandum-from-moulton-to-guinier. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

[*"-A-l I L

;$L{l s

NS$ |

$Jt{

- i t I ,,$

+

$ q'x*

Y(cr

*ott

JF

C

\

)Ad

1".

J

5?-(

.N

S

)$t

s\.-\s{*\

s\\)

\'

S

o

*

I

\".-S

$.'--

.*.-

0i-1.

l

i8l

h-s

<

i

-9 trr J

- 6'tr)

srt 6

l{67 f.lY 7}s-a-,1,-

f -t {-rprr),-{a ,

ZZ- €z.q- A't , L*n l,qtl,.- .

lr

Q..- U'Dh'-J

f A C,ruu, I c-"r..,A'^r.,.-{

Iir:-t--l*"., {7Y

dul-,,, i-t )ir. q ssl, / o(

Pcrt ,,o-a) uL-

fls-pe. 7zs 4l 3'37

f<-l\-,L(aj/n fu- LDu,/

(""'- =-

-(t *)

\^-l c vv(

L 6-,^rL

'i*6 rcu,l . tr*<-e,tp. $-

4^L , fu,'1. T a.t),

f S,rr.

G-,1^ u

* )k /!Dl

E$in. Io - )

(-,..!- 6;, ,l,--t

T c-o-Ll)1-

it n*

(, gr) (rl rs..,-L Lt I T.--.+1)ce ) 6-r,.",

ft1,n.-h'tt.(*rl u€ pol6-l--\ Uc

$^ c,,-^,. l 'bb.y-Ly-?.!-@-

,fu ''

54 Y { eqp l/ z7-

o€ !1o\' r- -6. pr-cl,n,* *,

l,-' ,n , c - I b*L 6- r s' k/h's 4'-t

-_)

o € 6 e-L-,-4c-: / L[2?-**l I No o#*r" t" i so/n/<- ru;'[L-o

()(' l- ,1.^s,'r- o-"o(yscA, fu...L-k( W,-lr--r-- olgo un)-

.a,lt -O-),,a^nL*

*"rD,*

( Ga-,'!,,̂)

V

.L

A

I

"bl-r-^-.r,","-,,^oL*r^ n /,, ob *ur-,^-

,^-^,,(*+rj &b, 4 +,

l-\tt O -zt-(49aru4.

I li.,^-

'16( " eaJa)

aw.*-,,J<-/ -4UL<aL ".A {1L L

M ?*i#"W ,'l;*- l" tua-,*,) le.-L /a(h) r