Watson v. Fort Worth Bank and Trust Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 14, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Watson v. Fort Worth Bank and Trust Brief Amicus Curiae, 1987. 58a7e2b5-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/791e291c-725b-4f0c-b56f-07e667377416/watson-v-fort-worth-bank-and-trust-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

£ i~ L I S

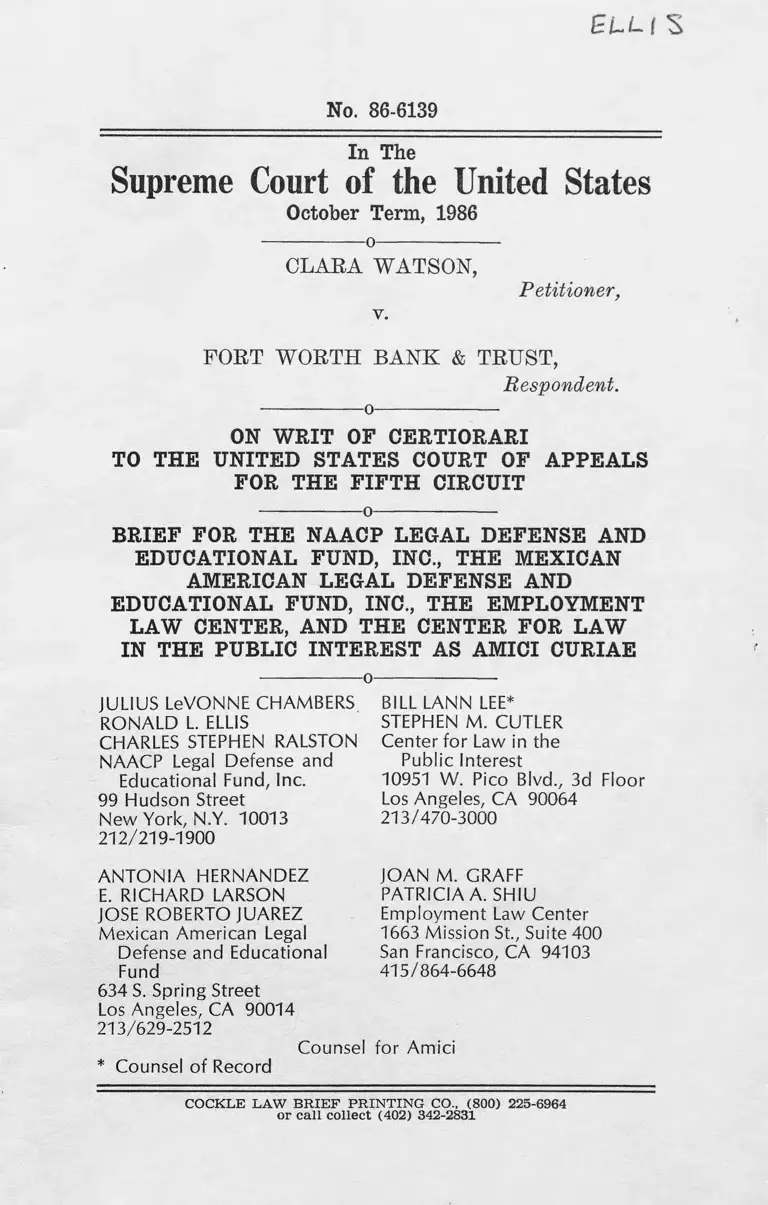

No. 86-6139

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1986

----------------- — o------------------------- -

CLARA WATSON,

Petitioner,

v.

FORT WORTH BANK & TRUST,

Respondent.

■--------- — ------------ o ---------------------------------

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

----------------o-------------------

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE MEXICAN

AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE EMPLOYMENT

LAW CENTER, AND THE CENTER FOR LAW

IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST AS AMICI CURIAE

•— — ------------------- o ---------------------------------------------

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS BILL LANN LEE*

RONALD L. ELLIS STEPHEN M. CUTLER

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON Center for Law in the

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

212/219-1900

ANTONIA HERNANDEZ

E. RICHARD LARSON

JOSE ROBERTO JUAREZ

Mexican American Legal

Defense and Educational

Fund

634 S. Spring Street

Los Angeles, CA 90014

213/629-2512

Counsel for Amici

* Counsel of Record

Public Interest

10951 W. Pico Blvd., 3d Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90064

213/470-3000

JOAN M. GRAFF

PATRICIA A. SHIU

Employment Law Center

1663 Mission St., Suite 400

San Francisco, CA 94103

415/864-6648

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO.. (800) 225-6964

or call collect (402) 342-2831

1

TABLE OF AU THORITIES.......................................... iii

INTEREST OF AMICI CU R IA E.................................. 1

INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUM ENT........................................ 5

ARGUMENT....................................................................... 6

I. THE LANGUAGE OF TITLE VII SUPPORTS

THE APPLICATION OF DISPARATE IM

PACT ANALYSIS TO SUBJECTIVE CRI

TERIA ....................................................................... 7

A. Section 703(a)(2) Is A Crucial Element of

Title V II ’s Comprehensive Enforcement

Scheme ................................................................. 7

B. Section 703(a)(2) Draws No Distinction

Among Different Employment Practices....... 8

C. The Asserted Exemption From § 703(a) (2) Is

Found Nowhere in the Language of Title VII,

and Must Be Rejected........................................ 9

II. THE COURT’S DECISIONS SUPPORT A P

PLICATION OF DISPARATE IMPACT

ANALYSIS TO SUBJECTIVE C R IT E R IA ..... 10

III. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY SANCTIONS AP

PLICATION OF THE DISPARATE IMPACT

ANALYSIS TO SUBJECTIVE PRACTICES... 13

IV. THE ADMINISTRATIVE INTERPRETA

TION OF TITLE VII SUPPORTS THE AP

PLICATION OF DISPARATE IMPACT

ANALYSIS TO SUBJECTIVE EMPLOY

MENT PRACTICES.................................... 20

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Page

Y. APPLICATION OF THE DISPARATE IM

PACT ANALYSIS TO SUBJECTIVE PRAC

TICES FURTHERS THE PRIMARY PRO

PHYLACTIC PURPOSE OF TITLE V I I ......... 23

A. Title VII “ Prohibits All Practices in What

ever Form Which Create Inequality in Em

ployment Opportunity” ...................................... 24

B. Title VII Requires That Employers “ Self-

Examine and Self-Evaluate Their Employ

ment Practices” .................................................. 25

CONCLUSION ............................................ 30

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Pages

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ..................................................6,10,13,14, 21, 25, 26

Atonio v. Wards Cove Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477

(9th Cir. 1987)............................................................. 3, 7, 26

Barnett v. W.T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d 543 (4th. Cir.

1975)................................................................................... 27

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457

F.2d 1377 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982

(1972) ......................... .............................. ..................... 10

California Federal Savings and Loan Association

v. Guerra,— U.S. —, 107 S.Ct. 683 (1987) ............... 2

Chance v. Bd. of Examiners, 330 F.Supp. 203

(S.D.N.Y. 1971), a ff ’d, 458 F.2d 1167 (2d Cir.

1972)................................................................. 24

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976) ................. 5, 8

Chicago Police Officer’s A ss’n v. Stover, 552 F.2d

918 (10th Cir. 1977) ...................................................... 11

City of Los Angeles v. Manhart, 435 U.S. 702 (1978) 8

Colby v. J.C. Penney Co., 811 F.2d 1119 (7th Cir.

1987)................................................................................... 8

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982) ...............5, 7, 8,10,

11,14, 25

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) ....... 6, 10,11,13

Espinoza v. Farah Mfg. Co., 414 U.S. 86 (1973) ........... 21

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) ....................................................................... 9,18

Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567

(1978)...............................................................................12,13

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125 (1976) 21

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Pages

General Tel. Co. of Southwest v. Falcon, 457 U.8.

147 (1982) ....................................................................... i i

Goodman v. Luhens Steel Co., — U.S. —, 107 S.Ct.

2617 (1987) ..................................................................... 4

Griffin v. Carlin, 755 F.2d 1516 (11th Cir. 1985) .........25, 26

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ......passim

Harrison v. Lewis, 559 F.Supp. 943 (D.D.C. 1983) ....... 29

Hawkins v. Bounds, 752 F.2d 500 (10th Cir. 1985) ....... 25

Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 319 F.Supp 314

(E.D. La. 1970) ............................................................. 11

Hishon v. King d Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984).....4, 5, 9,10

Int’l Bhd. of Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324 (1977) ............................................ 9,10,11,13,14

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454

(1975)................................................................................. 14

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara

County, Calif., — U.S. —, 107 S.Ct. 1442 (1987) ....... 23

Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers’ International

Association v. EEOC, — U.S. —, 106 S.Ct. 3019

(1986)...............................................................................18, 21

Local 53 of the International Association of Heat

d Frost Insulators v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th

Cir. 1969) ....................................................................... 18

Local No. 93, International Association of Fire

fighters v. City of Cleveland, — U.S. —, 106

S.Ct. 3063 (1986) .......... 21

Lynch v. Alworth-Stephens Co., 267 U.S. 364 (1925) ... 8

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973)........................................................................... 4, 12,13

V

Morton v. Mancri, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) ........................... 9

Muller v. United States Steel Corp., 509 F.2d 923

(10th Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 825 (1975) ............. 27

Nanty v. Barrows Co., 660 F.2d 1327 (9th Cir.

1981)....................................................... 27

Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S. 136 (1977)............. 8

Nation v. Winn-Dixie Stores, Inc., 567 F.Supp.

997 (N.D. Ga.), a ff ’d on reh’g, 570 F.Supp. 1473

(N.D .Ga. 1983) ............................................................... 3

New York City Transit Authority v. Beazer, 440

U.S. 568 (1979) ............................................................. 10,11

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542

(1971) ................................................................................. 8,9

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340

(8th Cir.), vacated on other grounds, 423 U.S.

809 (1975)......................................................................... 27

Rowe v. General Motors Co., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir.

1972)....................................................................... 20

Sears v. Bennett, 645 F.2d 1365 (10th Cir. 1981),

cert, denied, 456 U.S. 964 (1982) ............... 1................. 11

Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249 (D.C. Cir. 1984),

cert, denied, 471 U.S. 1115 (1985) ................................ 25

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d

652 (2d Cir. 1971) ............... 1........................... ............... 26

United States v. Dillon Supply Co., 429 F.2d 800

(4th Cir. 1970) ............................................................... 19

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 695 F.2d 890

(5th Cir. 1983)......... 11

United States v. N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354 (8th

Cir. 1973) ......................................................................... 6, 26

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Pages

VI

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers Interna

tional Association, Local Union No. 36, 416 F.2d

123 (8th Cir. 1969) .......................................................... 18

United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979) ...14, 26

Wallace v. City of New Orleans, 654 F.2d 1042 (5th

Cir. 1981) ......................................................................... 11

Wambheim v. J.C. Penney Co., 705 F.2d 1492 (9th

Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 467 U.S. 1255 (1984)............. 8

Wilmore v. City of Wilmington, 699 F.2d 667 (3d

Cir. 1983) ......................................................................... 24

S tatutes and E xecutive Orders

Title Y II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e.................................. 2, 3, 4, 7, 8

§ 701(b)......................................................................... 9

§ 702............................................................................... 9

§ 703(a)..................................................................... passim

§ 703(e) ............. 9

§ 703(h) ..........................................................................9,14

§ 703(i) ......................................................................... 9

§ 704............................................................................... 18

§ 706(a)......................................................................... 18

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub.

L. No. 92-261, 86 Stat, 103............................................. 14,16

Executive Order 11246 ................................................. 23

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Pages

V ll

R egulations

Employment Tests by Contractors and Subcon

tractors: Validation, 33 Fed. Reg. 14392 (1968)....... 23

Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, 35

Fed. Reg. 12333 (1970) .................................................. 22

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Proce

dures, 29 C.F.R. § 1607 (1986)

■§1607.1 ......................................................................... 21

§ 1607.6 ....................................................................... 21,22

§ 1607.13 ....................................................................... 23

§1607.16 ........................................................................5,20

§1607.2 ......................................................................... 23

§ 1607.3 ..................................................................... 20, 23

L egislative H istory

H.R. Rep. No. 238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ....... 15,17,

18.19

S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 14 (1971)...........14,15,

17.19

Equal Employment Opportunities Enforcement

Act of 1971, Hearings before the Subcommittee

on Labor of the Senate Committee on Labor and

Public Welfare on S.2515, S.2617, and H.R.

1746, Oct. 4, 6 and 7, 1971................................................ 16

Equal Employment Opportunity Enforcement

Procedures, Hearings before the General Sub

committee on Labor of the House Committee on

Education and Labor on H.R. 1746, March 3, 4,

and 18, 1971 ................................................................... 16

110 Cong. Rec. (1964)

6548 ....................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Pages

14

V l l l

117 Cong. Rec. (1971)

32103 ............................................................................. 14

118 Cong. Rec. (1972)

7166 ............................................................................... 18

7167 ............................................................................... 18

7564 ............................................................................... 18

Oter A uthorities

American Psychological Association, American

Education Research Association and National

Council on Measurements in Education, Stan

dards for Educational and Psychological Test

ing (1985) ........... 28

Arvey & Campion, The Employment Interview: A

Summary and Review of Recent Research, 35

Personnel Psychology 281 (1982) ................................ 28

D. Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical Proof of Discrim

ination (1980 & 1986 Snpp.) .............................. 6, 25, 26, 27

Bartholet, Application of Title VII to .lobs in

High Places, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 947 (1982) ........... 28

W. Cascio, Applied Psychology in Personnel Man

agement (2d ed. 1982) ................................................ 6, 28

Comment, Applying Disparate Impact Theory to

Subjective Employee Selection Procedures, 20

Loy. L.A.L. Rev. 375 (1987) ..........................................3, 22

Cooper & Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A General Approach to

Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82

Harv. L. Rev. 1598 (1969) ...................... 18

Federal Personnel Manual, Chap. 335, Supplement

335-1 (1980) ............................................................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Pages

29

IX

TABLE OP AUTHORITIES— Continued

Pages

Gui on, Recruiting, Selection and Job Placement,

in Handbook of Industrial and Organizational

Psychology 799 (M. Dunnette ed. 1983)....................... 28

Lamber, Discretionary Decisionmaking: The Ap

plication of Title V II ’s Disparate Impact

Theory, 1985 U. III. L. Rev. 869 .................................... 3

R. Plumbley, Recruitment and Selection (1981) _____ 24

(1981)................................................................................. 24

B. Schlei and P. Grossman, Employment Discrimi

nation Law (2nd ed. 1983) .......................................... 25, 29

Stacy, Subjective Criteria in Employment Deci

sions Under Title VII, 10 Ga. L. Rev. 737 (1976) ...... 24

United States Comm’n on Civil Rights, For All the

People . . . By All the People—A Report on

Equal Opportunity in State and Local Govern

ment Employment (1969), reprinted in 118

Cong. Rec. 1817 (1972) .................................................. 15

No. 86-6139

--------o--------

Supreme

In The

Court of the United States

October Term, 1986

--------------o-----------------

CLARA WATSON,

Petitioner,

v.

FORT WORTH BANK & TRUST,

Respondent.

———--- -o------------------

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

----------------o--------- -—------

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE MEXICAN

AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE EMPLOYMENT

LAW CENTER, AND THE CENTER FOR LAW

IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST AS AMICI CURIAE

----------------o---------—------- -

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amicus NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. is a New York nonprofit organization that has liti

gated numerous cases on behalf of black persons seeking

vindication of their civil rights, including Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971). Amicus Mexican Ameri

can Legal Defense and Educational Fund, headquartered

in Los Angeles, is a national civil rights organization that

has brought various lawsuits on behalf of Latinos subject

to discrimination in employment, public education, voting

rights and other areas of public life. Amicus Employment

Law Center, a project of the Legal Aid Society of San

Francisco, has represented women and minorities in nu-

1

merous employment discrimination eases, including Cali

fornia Federal Savings and Loan Association v. Guerra,

— U.8. —, 107 S.Ct. 683 (1987). Amicus Center for Law

in the Public Interest is a non-profit corporation located

in Los Angeles that for many years has prosecuted civil

rights and public interest lawsuits, including employment

discrimination class actions on behalf of women and minor

ities. Letters from the parties consenting to the filing of

this brief have been filed with the Court.

----------------o----------------

INTRODUCTION

The Court granted certiorari to consider whether an

employer’s selection or promotion practices may be in

sulated from disparate impact scrutiny under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. ■§§ 2000e to 2000e-

17 (1982 ed. & Supp. I l l ) , simply because they are subjec

tive. Amici will address the merits of the issue so as to

respond to the arguments made by the United States in its

amicus curiae brief supporting the petition for certiorari.

Preliminarily, however, we have grave doubts that this

important legal issue is properly presented by the case

now before the Court. The record reflects that the peti

tioner relied upon disparate treatment analysis in the trial

court, and could not prove a case of denial of promotions

based on disparate impact.1 Even if this Court were to

'The evidence presented at trial was typical of a disparate

treatment case. Petitioner testified as to her qualifications and

the fact that she had applied for three promotions; the defen

dant presented evidence that purported to establish legitimate,

non-discriminatory reasons for each promotion action. Those'

reasons focused on the relative qualifications of the persons

selected and the legitimacy of the employer's actions. Evidence

was also presented showing a low hire rate and slower promo

tion rate for blacks.

The district court found—and those findings are not chal

lenged here—that throughout the relevant time period, the re

spondent employed a total of only 15 blacks, and that at any

one time, the number of blacks employed never exceeded eight.

(Continued on following page)

3

hold that disparate impact analysis should be applied to

subjective employment practices, as we urge below, the

petitioner would be unable to establish a violation of Title

VII on that basis. Accordingly, it is appropriate to dis

miss certiorari as improvidently granted.

Should the Court reach the merits in this—or another

—case, amici urge the Court to reject the government’s

proposed exemption for subjective employment practices.* 2

(Continued from previous page)

The particular complaint of the plaintiff is that she was dis-

criminatorily denied promotions on three occasions. The dis

trict court further found that, in addition to plaintiff, only one

other black had applied for promotions given to whites. Thus,

blacks applied for and were denied a total of five promotions.

Memorandum Opinion of District Court at 13 (Nov. 21, 1984);

testimony of Sylvia Harden, Tr. Vol. ill, at 98-99. Such num

bers do not permit a showing of disparate impact, since they

cannot establish any pattern of the effect of an employment

practice. The government agrees. See Brief for the United States

as Amicus Curiae, at 20 n.16.

2The line between subjective and objective employment

practices is not as bright as the government suggests.

[Ajlmost all criteria necessarily have both subjective and

objective elements. For example, while the requirement

of a certain test score may appear "objective," the choice

of skills to be tested and of the testing instruments to

measure them involves "subjective" elements of judgment.

Such apparently "subjective" requirements as attractive ap

pearance in fact include "objective" factors. Thus the terms

represent extremes on a continuum . . . .

Atonio v. Wards Cove Packing Co,, 810 F.2d 1477, 1485 (9th

Cir. 1987) (en banc). In the words of one commentator, "[m ]ost

employment decisions contain some element of subjectivity."

Comment, Applying Disparate Impact Theory to Subjective Em

ployee Selection Procedures, 20 Loy. L.A.L. Rev. 375, 400 (1987).

See also Lamber, Discretionary Decisionmaking: The Applica

tion of Title VIl's Disparate Impact Theory, 1985 U. III. L. Rev.

869, 874 n.14 ("In a sense, all decisions—from the pure hunch

to the choice of using a dearly defined objective rule— involve

discretion."). Cf. Nation v. Winn-Dixie Stores, Inc., 567 F.Supp.

997, 1005 n.20 (N.D. Ga.) ( " [ ! ] t is especially difficult in the

context of promotions to formulate employer decisionmaking

criteria that are comoletelv free of subjectivity."), aff'd on reh'g,

570 F.Supp. 1473 (N.D. Ga. 1983).

4

Such an exemption is directly contrary to Title V II ’s plain

meaning, the prior decisions of this Court, specific legis

lative history, the Justice Department’s own guidelines on

employee selection, and the prophylactic purpose of the

statute.

The government would permit an employer to make

personnel decisions on the basis of “ subjective” criteria—

even if those criteria are “ unrelated to measuring job

capability,” Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 432

(1971), and result in the disproportionate exclusion of

minorities and/or women— so long as those decisions are

made in good faith. The alternative, it is argued, would

be to interfere with the employer’s management preroga

tives. See Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

at 14-17. Yet management prerogatives are necessarily cir

cumscribed by Title V II ’s essential purpose of “ achiev-

[ing] equality of employment opportunity].” Griggs,

401 U.S. at 429. They cannot be permitted to shield dis

crimination, “ subtle or otherwise.” McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 801 (1973). Accordingly, this

Court has consistently rejected arguments founded on the

notion of employer discretion where that discretion would

be exercised in a manner contrary to Title V II ’s prohibi

tory pronouncements. In Hishon v. King <& Spalding, 467

U.S. 69, 78 (1984), for example, the Court held that Title

VII applied to the partnership decisions of a law firm, not

withstanding the possible infringement on that firm ’s

rights of expression and association. Cf. id. at 80 n.4

(Powell, J., concurring) (“ [L]aws that ban discrimination

. . . may impede the exercise of personal judgment . . . , ” ).

And last term, the Court rejected government arguments

based on policy considerations relating to the prerogatives

of unions. Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., — U.S. — —,

107 S.Ct. 2617, 2624-25 (1987).3 Whether or not such pre

rogatives are diminished by the application of disparate

35ee Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae at 19-24,

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 107 S.Ct. 2617 (1987).

5

impact analysis to subjective employment practices, “ Con

gress has made the choice, and it is not for us to disturb

it.” Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840, 864 (1976) (re

jecting government’s proffered interpretation of Title YII

in face of plain meaning of statute and its legislative his

tory).

----------------o----------------

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

“ A disparate-impact claim reflects the language of

§ 703(a)(2),” Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 448 (1982).

The plain terms of the statute provide absolutely no basis

for exempting the entire category of subjective employ

ment practices from the scope of § 703(a) (2). Had Con

gress intended to exempt subjective criteria, it well knew

how to do so. See Iiishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S.

69, 77-78 (1984) (“ When Congress wanted to grant an

employer . . . immunity, it expressly did so.” ).

The legislative history of the 1972 amendments to

Title VII demonstrates that Congress ratified and en

dorsed the Court’s decision in Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971), and contemplated its application to

all employment practices, including subjective criteria, hav

ing a discriminatory impact on minorities and women. In

particular, Congress specifically indicated, with respect

to the federal government’s personnel system, that Griggs

applied to its subjective selection criteria. The adminis

trative regulations issued by the agencies charged with

enforcement responsibility confirm that Congress intended

the disparate impact analysis to apply to “ the full range

of assessment techniques from traditional paper and pen

cil tests . . . through informal or casual interviews and un

scored application forms.” 29 C.F.R. § 1607.16Q (1986).

Limiting § 703(a)(2) disparate impact analysis to ob

jective criteria would frustrate Title V II ’s primary goal

of “ achiev[ing] equality of employment opportunities.”

Griggs, 401 U.S. at 429. Moreover, the exclusion of sub

jective practices from dispai'ate impact analysis would

6

make employers less inclined to “ ‘ self-examine and self-

evaluate [their] employment practices,’ ” Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975) (quoting

United States v. N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354, 379 (8th

Cir. 1973)), as contemplated by Title VII.

----------------o----------------

ARGUMENT

The government would exempt from disparate impact

analysis all practices and procedures of a subjective nature

— i.e., discretionary selection devices such as evaluative

interviews, performance appraisals, and essay examina

tions. Application of the disparate impact analysis would

be limited to objective criteria—i.e., non-discretionary se

lection devices such as height and weight requirements,

see Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321, 324 (1977), me

chanically scored intelligence tests, Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424, 427-28 (1971), and diploma requirements,

id.4 Accordingly, the government would make intent the

sole focus of most Title VII litigation. See supra note 2.

But just like their non-discretionary counterparts, discre

tionary selection criteria can “ operate as ‘ built-in head

winds’ for minority groups [and women],” Griggs, 401

U.S. at 432, even in the absence of discriminatory intent.

See infra at 24-25.5 Whether an employment practice is ob

jective or subjective should not and cannot “ provide a line

4Cf. W. Cascio, Applied Psychology in Personnel Manage

ment 129 (2d ed. 1982) ("The method of scoring a test may be

objective or non-objective. In the former case, there are fixed,

impersonal standards for scoring . . . . On the other hand, the

process of scoring essay tests and certain types of personality

inventories . . . may be quite subjective . . . ." ) ; D. Baldus & J.

Cole, Statistical Proof of Discrimination § 1.23 (1980 & 1986

Supp.) (distinguishing between "nondiscretionary criteria" and

criteria that are "discretionarily . . . applied"). But see supra

note 2.

5Under the government's proposed exemption for subjec

tive criteria, a non-discretionary requirement of supervisory ex

perience might be shielded simply by taking that experience

into account through a discretionary requirement of "leadership"

ability. See infra at 26.

7

of demarcation to guide courts in choosing the appropriate

analytic tool in a Title VII discrimination case.” Atonio

v. Wards Cove Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477, 1485 (9th Cir.

1987) (en banc).

I. THE LANGUAGE OF TITLE VII SUPPORTS THE

APPLICATION OF DISPARATE IMPACT AN

ALYSIS TO SUBJECTIVE CRITERIA

As the Court noted in Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S.

440, 448 (1982): “ A disparate-impact claim reflects the

language of § 703(a) (2 ).” Nothing in the statute can be

read to exclude subjective employment practices from that

section’s reach.

A. Section 703(a)(2) Is a Crucial Element of Title

VII’s Comprehensive Enforcement Scheme

The two subparts of § 703(a) reflect the intent of Con

gress to proscribe “ not only overt discrimination but also

practices that are fair in form, but discriminatory in oper

ation.” Griggs, 401 U.S. at 431.

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any

individual with respect to his compensation, terms,

conditions, or privileges of employment, because of

such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees

or applicants for employment in any way which would

deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employ

ment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his

status as an employee, because of such individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

42 U.S.C. S 2000e-2(a). Section 703(a)(2) is concerned

with “ the consequences of employment practices,” Griggs,

401 U.S. at 432 (emphasis in original), for which disparate

impact analysis is appropriate.

The § 703(a) enforcement scheme evidences no intent

to restrict a plaintiff to subpart (1) as an exclusive remedy

8

for any category of employment practices. Section 703(a)

is a comprehensive framework, embracing all forms of

employment discrimination by providing overlapping guar

antees against both the overt discrimination to which § 703

(a) (1) is primarily directed,6 as well as the denial of equal

employment “ opportunities” with which § 703(a) (2) is

concerned, Teal, 457 U.S. at 449; Griggs, 402 U.S. at 431.

B. Section 703(a)(2) Draws No Distinctions Among

Different Employment Practices

Section 703(a)(2), by its terms, prohibits practices

that “ limit, segregate, or classify . . . employees or appli

cants . . . in any way” so as to deprive an individual of

employment opportunities on the basis of race, sex, or

some other protected characteristic. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2

(a)(2) (emphasis added). It nowhere suggests that sub

jective practices should be exempted, and indeed, draws

no distinction between objective and subjective employ

ment criteria. Accordingly, the government’s attempt to

draw such a distinction should be rejected: “ ‘ [T]he

plain, obvious and rational meaning of a statute is always

to be preferred to any curious, narrow, hidden sense that

nothing but the exigency of a hard case and the ingenuity

and study of an acute and powerful intellect would dis

cover.’ ” Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. at 848 (quoting

Lynch v. Alwortli-Stephens Co., 267 U.S. 364, 370 (1925)).

The most natural reading of § 703(a) (2) is that all em

ployment practices are covered by its broad prohibition

and may come under disparate impact scrutiny. As this

6A violation of § 703(a)(1) may also be established by show

ing that a practice is facially discriminatory. See City of Los

Angeles v. Manhart, 435 U.S. 702 (1978); Phillips v. Martin Mari

etta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971). Several lower courts have held

that disparate impact challenges may also be brought under

§ 703(a)(1). See, e.g., Colby v. J.C. Penney Co., 811 F.2d 1119,

1127 (7th Cir. 1987); Wambheim v. J.C. Penney Co., 705 F.2d

1492, 1494 (9th Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 467 U.S. 1255 (1984);

cf. Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S. 136, 144 (1977) (The

Court "need not decide whether . . . it is necessary to prove

intent to establish a prima facie violation of § 703(a)(1).").

9

Court noted in Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. 747, 763 (1976) (emphasis added): “ Congress in

tended to prohibit all practices in whatever form which

create inequality in employment opportunity due to dis

crimination on the basis of race, religion, sex, or national

origin.”

C. The Asserted Exemption From § 703(a) (2) Is

Found Nowhere in the Language of Title VII,

and Must Be Rejected

The government would exempt a whole category of

employment practices from § 703(a) (2) ’s coverage, though

no such exemption appears in the language of that section

or the other provisions of Title VII. That absence of text

ual support is telling: “ When Congress wanted to grant

an . . . immunity, it expressly did so. ’ ’ llishon v. King &

Spalding, 467 U.S. 69, 77-78 (1984) (rejecting assertion of

immunity for partnership decisions); Int’l Bhd. of Team

sters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 349 (1977) (“ Were it

not for § 703(h), the seniority system in this case would

seem to fall under the Griggs rationale.” ).

For example, Congress specifically exempted the use

of bona fide occupational qualifications based on religion,

sex or national origin, § 703(e)(1), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e)

(1), see Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542,

544 (1971); bona fide seniority or merit systems, § 703(h),

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h), see Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 350-56

(exemption applying to '§ 703(a) (2) cases only); ability

tests “ not designed, intended or used to discriminate,”

§ 703(h), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h), see Griggs, 401 U.S. at

433-36; and certain preferential treatment of Indians,

§ 703(i), 42 U.S.C. '§ 2000e~2(i), see Morton v. Mancari,

417 U.S. 535, 545 (1974). Congress also provided express

exemptions for the employment practices of Indian tribes

and certain agencies of the District of Columbia, § 701(b)

(1), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(b) (1 ); small businesses and bona

fide private membership clubs, !§ 701(b) (2), 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e(b) (2) ; certain religious organizations, § 702, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-l; and certain religious educational insti

tutions, <§ 703(e) (2), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e) (2).

10

Here, the government would have this Court create—

where Congress did not—-a § 703(a) (2) exemption for sub

jective employment practices and exclude them from dis

parate impact scrutiny. Because that asserted exemption

falls outside the express language of Title VII, however,

it must be rejected. See Hishon, 467 U.S. at 77-78.

II. THE COURT’S DECISIONS SUPPORT APPLICA

TION OF DISPARATE IMPACT ANALYSIS TO

SUBJECTIVE CRITERIA

This Court’s decisions are consistent with the above-

proffered construction of § 703(a) (2). In Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 432-33 (1975), the Court ac

knowledged difficulty in determining whether subjective

appraisals, executed as part of a validation study, had

measured job-related ability. The same concern exists

when such appraisals constitute the employment practice

being challenged. Implicit in the Court’s opinion is the

recognition that, notwithstanding a lack of discriminatory

intent, minorities and women might be adversely affected

by discretionary practices that do not closely relate to job

capability.

While the Court has not specifically discussed the ap

plication of disparate impact analysis to subjective employ

ment practices, it has never excluded any practice from

the scope of § 703(a)(2).7 Moreover, the Court has con

7Those practices "dearly fall[ing] within the literal lan

guage of § 703(a)(2)/' Teal, 457 U.S. at 448, include written

examinations, Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 425; Griggs, 401 U.S. at

433, educational requirements, id., height and weight require

ments, Dothard, 433 U.S. at 328-29, a policy against employing

persons who use narcotic drugs, New York City Transit Authority

v. Beazer, 440 U.S. 568, 584-87 (1979), and a residual category

of practices that perpetuate the effects of prior discrimination,

Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 349 ("One kind of practice 'fair in form,

but discriminatory in operation' is that which perpetuates the

effects of discrimination."). Of course, within such a residual

category, one would expect to find subjective, as well as ob

jective employment practices. See Brown v. Gaston County

Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377, 1382 (4th Cir.) ("[ejlusive

[and] purely subjective standards" may effectively perpetuate

past discrimination), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982 (1972).

11

sistently spoken in broad-brush terms such as “ practices,”

“ criteria,” and “ barriers” —terms that clearly encompass

both subjective and objective practices—in discussing and

applying the disparate impact theory.8

That subjective practices are susceptible to challenge

under the disparate treatment analysis of 703(a) (1) does

not mean that they are not susceptible to challenge under

the disparate impact analysis of § 703(a) (2). As the Court

acknowledged in Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 335 n.15, “ [ejither

theory may, of course, be applied to a particular set of

facts.” An objective selection criterion may be discrim

inatory either because its adoption is traceable to a dis

criminatory motive,9 or because the practice has an un

justified discriminatory effect. The same is true for a sub

jective selection criterion. The government, without men

tioning Teamsters, argues that this Court expressly de-

8See, e.g., Griggs, 401 U.S. at 430 ("practices, procedures,

or tests"); id. at 431 ("criteria for employment"); id. at 432

("any given requirement"); Dothard, 433 U.S. at 328 ("arbitrary

barrier to equal employment opportunity"); Beazer, 440 U.S.

at 584 ("an employment practice has the effect of denying . . .

equal access to employment opportunities"); Teal, 457 U.S. at

448 ("nonjob-related barrier"). Cf. General Tel. Co. of South

west v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147, 159 n.15 (1982) ("Title VII pro

hibits discriminatory employment practices," including "sub

jective decisionmaking processes.") (emphasis in original).

9See, e.g., United States v. Georgia Power Co., 695 F.2d

890, 893 (5th Clr. 1983) (non-discretionary seniority system

"maintained out of an unlawful purpose"); Sears v. Bennett,

645 F.2d 1365, 1374 (10th Cir. 1981) (seniority system "main

tained with the purpose of discriminating against black em

ployees"), cert, denied, 456 U.S. 964 (1982); Chicago Police

Officer's Ass'n v. Stover, 552 F.2d 918, 921-22 (10th Cir. 1977)

(case remanded for determination of whether employment test

having discriminatory impact was adopted with discriminatory

intent); cf. Wallace v. City of New Orleans, 654 F,2d 1042, 1047

(5th Cir. 1981) (police department's adoption of height/weight

requirement held not a product of intentional discrimination);

Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 319 F.Supp. 314, 318 (E.D.

La. 1970) ("There was no claim that defendants had adopted

the tests for the express purpose of capitalizing on these dif

ferential passing rates . . . .").

12

dined to apply § 703(a) (2) to discretionary employment

practices in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792 (1973), and Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438

U.S. 567 (1978). See Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae at 11-12. A close look at those cases, however, dem

onstrates otherwise.

In McDonnell Douglas, there was simply no assertion

of disparate impact. The plaintiff’s claims were limited

to disparate treatment and retaliation under §§ 703(a)(1)

and 704, see 411 U.S. at 796-98, 807; a § 703(a) (2) claim

was never made. Indeed, the plaintiff made no effort to

establish any group-wide effects of the practice at issue.

See id. at 805. Thus, the case neither holds nor implies

that § 703(a) (2) disparate impact analysis is inapplicable

to subjective practices.

Nor does Furnco support such a contention.10 The

Court granted certiorari “ to consider important questions

raised by th[e] case regarding the exact scope of the prima

facie case under [the] McDonnell Douglas [disparate treat

ment approach] and the nature of the evidence necessary

to rebut such a case.” Id. at 569. The Court agreed with

the court of appeals that the plaintiff had made out a

prima facie case of disparate treatment, but reversed on

the issue of the defendant’s burden of rebuttal. The gov

ernment’s assertion that the Court “ expressly refused to

apply disparate impact analysis,” Brief for the United

States as Amicus Curiae at 12, is incorrect: A disparate

impact claim was not before the Court. While the Court

10ln Furnco, several black applicants for employment chal

lenged, on both disparate impact and disparate treatment

grounds, an employer's practice of hiring only those applicants

who were known by the superintendent or who were otherwise

recommended. The district court rejected both claims, finding,

on the impact claim, that blacks as a group were not dispro

portionately excluded by the employer's selection process. 438

U.S. at 572. The court of appeals reversed on the disparate

treatment claim, id. at 573-74, and the employer sought and

petitioned for certiorari only on disparate treatment issues.

See id. at 574 n.6 (questions presented in petition for certiorari).

13

noted that the selection procedure at Lsue in F'urnco “ did

not involve employment tests which we [re] dealt with in

Griggs . . . and in Albemarle . . ., or particularized require

ments such as the height and weight specifications con

sidered in Dothard . . id. at 575 n.7, it cannot be con

cluded that the Court intended this bare listing to announce

a decisional rule restricting use of the disparate impact

analysis to objective criteria.11 Although the government

fails to mention it, the Court also noted, in the same dis

cussion, that Furnco “ was not a . . . case like Teamsters

. . id., in which the employment practices at issue wrere

discretionary in nature. See Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 338

n.19. There is, in short, nothing in Griggs or its progeny

that would limit use of the disparate impact analysis to

objective criteria.

III. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY SANCTIONS APPLICA

TION OF THE DISPARATE IMPACT ANALYSIS

TO SUBJECTIVE PRACTICES

While “ [undoubtedly disparate treatment was the

most obvious evil Congress had in mind when it enacted

Title V II” in 1964, Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 335 n.15, “ it

was clear to Congress that ‘ [t]he crux of the problem

[was] to open employment opportunities for Negroes in

occupations which have been traditionally closed to them,’

“ First, the complained-of practice in Furnco was itself non-

discretionary or objective in nature: The employer simply

"refus[ed] to consider . . . applications at the gate." Furnco,

438 U.S. at 576 n.8. Second, while the employment practices in

Griggs, Albemarle, and Dothard all might have been susceptible

to disparate treatment analysis, in none of those cases would

the McDonnell Douglas approach have been appropriate. To

make out a prima facie case under McDonnell Douglas, the

plaintiff must show "that he . . . was qualified for [the] job"

at issue. 411 U.S. at 802 (emphasis added). However, the

plaintiffs in Griggs, Albemarle, and Dothard brought suit be

cause discriminatory selection criteria had rendered them "un

qualified." Thus, perhaps the Court meant only to suggest that

the case before it was (unlike Griggs, Albemarle, and Dothard)

susceptible to the McDonnell Douglas approach, and not that

the plaintiff was foreclosed from making a disparate impact

challenge.

14

110 Cong. Rec. 6548 (1964) (remarks of Sen. Humphrey),

and it is to this problem that Title VIPs prohibition against

racial discrimination in employment was primarily ad

dressed.” United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193,

203 (1979). By 1972, when it enacted several major amend

ments to Title VII, Congress fully understood that the

opening of those opportunities could not be achieved by

the eradication of just intentional discrimination. See

S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong., 1st Seas. 14 (1971) [herein

after “ S. Rep. No. 415” ] (“ [W]here discrimination is in

stitutional, rather than merely a matter of bad faith, . . .

corrective measures appear to be urgently required.” ) ;

see also 117 Cong. Rec. 32103 (Sept. 16, 1971) (remarks of

Rep. Fraser) (“ Often the source of discriminatory pat

terns is inertia rather than deliberate intent. But that

does not lessen the injustice and economic damage done to

the recipients.” ).

The 1972 amendments, among them a broadening of

§ 703(a)(2) to include “ applicants for employment,” see

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. No.

92-261, 86 Stat. 103, 109, were the result of a thorough re

view by Congress of both the statute and the existing case

law, including this Court’s Griggs decision. Indeed, “ [t]he

legislative history . . . demonstrates that Congress recog

nized and endorsed the disparate-impact analysis employed

by the Court in Griggs,” Teal, 457 U.S. at 447 n.8, and

contemplated its application to all employment practices

having a discriminatory effect.12

In extending to state and municipal employees the

protections of Title VII—“ as interpreted by Griggs,” id.

12This Court has relied upon the 1972 legislative history

not only in Teal, 457 U.S. at 447 n.8, but also in Franks, 424 U.S.

at 764 n.21, 796 n.18 (Powell, J., concurring in part and dis

senting in part), Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 420-21, and Johnson

v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454, 459 (1975). Compare

Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 354 n.39 (little, if any, weight given to

1972 legislative history in light of clear language of § 703(h),

which was unaffected by 1972 amendments).

15

at 449—Congress was concerned with “ both institutional

and overt discriminatory practices,” and specifically iden

tified “ stereotyped misconceptions by supervisors regard

ing minority group capabilities” as having perpetuated

the effects of past discrimination. H.R. Rep. No. 238, 92d

Cong., 1st Sess. 17 (1971) [hereinafter “ H.R. Rep. No.

238” ] (emphasis added); see also S. Rep. No. 415, at 10.

Congress also relied upon a report authored by the United

States Commission on Civil Rights, which specifically iden

tified “ supervisory ratings” as a “ [b]arrier[] to equal

opportunity.” U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, For All

the People . . . By All the People—A Report on Equal

Opportunity in State and Local Government Employment

119 (1969), reprinted in 118 Cong. Rec. 1817 (1972). See

Teal, 457 U.S. at 449 n.10.

The extension of Title VII to federal employees was

grounded in similar concerns about both subjective and

objective practices. Quoting the presidential memorandum

accompanying Executive Order 11478, both Committee re

ports declared that “ discrimination of any kind based on

factors not relevant to job performance must be eradicated

completely from Federal employment.” H.R. Rep. No.

238, at 22-23; S. Rep. 92-415, at 13 (emphasis added).13

Indeed, legislative history is particularly instructive

with regard to the selection procedures of the federal gov

ernment. At the Senate hearings, Rep. Fauntroy of the

District of Columbia testified concerning the numerous

complaints received from his constituents regarding dis

crimination by federal agencies. He was particularly crit

ical of the Civil Service Commission’s focus on attempting

to find supervisors with malicious intent “ rather than

focusing on personnel policies that have the inherent ef-

13Congress was well aware of the widespread existence of

discretionary employment practices in the federal government.

See H.R. Rep. No. 238, at 24 (referring to employees' fears that

administrative complaints "will only result in antagonizing their

supervisors and impairing any hope of future advancement.");

S. Rep. No. 415, at 14 (same).

feet of discriminating against black, Spanish surname and

women employees.” 14

In the course of the hearings in the House of Rep

resentatives on what was to become the 1972 Act, there was

a specific focus on the question of whether the Civil Ser

vice Commission had validated all of its selection pro

cedures and instruments. Thus, the Chair of the House

Committee asked not only whether Civil Service tests and

written examinations had been validated, but also if other

selection techniques had been validated.15 The Civil Ser

vice Commission, in reply, identified selection techniques

other than tests as including the evaluation of the experi

ence and training of applicants or employees, and went on

to state: “ In a few instances interviews are a part of

the examination process. In other cases, and in the pro

motion program particularly, the appraisals of an indi

vidual’s job performance and potential are considered in

relation to the job to be filled.” 16 17 With regard to all these

qualification requirements, the Civil Service Commission

claimed that: “ The showing of direct relationships of job

demands to the qualification requirements . . . is fully in

conformity with the Supreme Court decision in Griggs v.

Duke Power Co.” 11

16

14Equal Employment Opportunities Enforcement Act of

1971, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate

Committee on Labor and Public Welfare on S.2515, S.2617, and

H.R. 1746, Oct. 4, 6 and 7,1971, p. 205.

15Letter to John H. Dent, Chairman, General Subcommittee

on Labor, Committee on Education, and Labor, U.S. House of

Representatives, from Irving Kator, Assistant Executive Director,

United States Civil Service Commission, April 23, 1971, repro

duced in Equal Employment Opportunity Enforcement Proced

ures, Hearings before the General Subcommittee on Labor of the

House Committee on Education and Labor on H.R 1746 March

3, 4, and 18, 1971, pp. 382-83.

16ld. at 383.

17/d. As part of its submission, the Civil Service Commis

sion introduced into the record the text of the 1969 Federal

Personnel Manual Supplement (FPM) 335-1. Evaluation of Em-

(Continued on following page)

17

Given the criticisms of the Commission it had heard,

Congress was understandably skeptical. Therefore, the

House and Senate reports echoed Representative Faun-

troy’s criticisms and instructed:

The Commission should be especially careful to en

sure that its directives issued to Federal Agencies

address themselves to the various forms of systematic

discrimination in the system. . . . It apparently has not

fully recognized that the general rules and procedures

that it his promulgated may in themselves constitute

systematic barriers to minorities and women.

Sen. Report No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., 1971, p. 14.

The Senate report goes on to state:

The Committee expects the Civil Service Commission

to undertake a thorough reexamination of its entire

testing and qualification program to ensure that the

standards enunciated in the Griggs case are fully met.

Id. at 14-15. See also H. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d Cong., 1st

Sess., 1971, pp. 24-25. In short, it is clear beyond any rea

sonable question that in 1972 Congress specifically man

dated that the Griggs rule apply to all forms of selection

and qualification requirements.

Finally, when Congress enacted the amendments to

Title VII, the courts had uniformly extended disparate im

(Continued from previous page)

ployees for Promotion and Internal Placement. Id. at 336-62.

The supplement required agencies to "give careful considera

tion" to which of the available evaluation instruments "are rele

vant to the job and are sound and dependable measures of the

qualifications needed." Id. at 337. The FPM went on to discuss

various evaluation instruments, including not only written and

other types of tests, but also interviews and procedures for ap

praisals and assessment of potential. Id. at 340-42. With regard

to all evaluation instruments, whether objective, subjective, or

mixed, the FPM required that an agency determine the effective

ness of the instrument through establishing its validity and dis

cussed and defined the three types of validity: content, construct

and criterion related. Id. at 342-43. Thus, the Civil Service Com

mission attempted to convince Congress that all of the methods

used in the federal service to select employees for jobs at all

levels had been fully validated.

18

pact scrutiny to subjective employment practices. And

“ in language that could hardly be more explicit,” Franks

v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. at 764 n.21, the

section-by-section analyses submitted to both Houses “ con-

firm[ed] Congress’ resolve to accept prevailing judicial

interpretations regarding the scope of Title V II,” Local

28 of Sheet Metal Workers’ International Association v.

EEOC, — U.S. —, —, 106 S.Ct. 3019, 3047 (1986) : “ In

any area where the new law does not address itself, or in

any areas where a specific contrary intention is not indi

cated, it was assumed that the present case law as devel

oped by the courts would continue to govern the applica

bility and construction of Title VII.” 118 Cong. Eec. 7166,

7564 (1972) (emphasis added).18

Congressional awareness of cases applying disparate

impact analysis to subjective employment practices ex

tended at least to United States v. Sheet Metal Workers

International Association, Local Union No. 36, 416 F.2d

123 (8th Cir. 1969), cited by the House Committee Report

as having “ contributed significantly to the federal effort

to combat employment discrimination,” H.R. Rep. No. 238,

at 13 n.14, and Local 53 of the International Association of

Heat & Frost Insulators v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir.

1969), cited by both the House and Senate Committee Re

ports as support for the “ complex and pervasive” nature

of employment discrimination, H.R. Rep. No. 238, at 8 n.2;

S. Rep. No. 415, at 5 n.l.19 Sheet Metal Workers involved

18Moreover, with respect to the new § 706(a), which gave

the EEOC more power to prevent persons from engaging in the

employment practices made unlawful by §§ 703 and 704, see

86 Stat. at 104, the section-by-section analyses expressly stated

that "the unlawful practices encompassed by [§§ ] 703 and 704,

which were enumerated in 1964 in the original Act, and as de

fined and expanded by the courts remain in effect." 118 Cong.

Rec. 7167, 7564 (1972) (emphasis added).

19!n explaining the "complex and pervasive" nature of em

ployment discrimination, the House and Senate Committee Re

ports also cited Cooper & Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under

(Continued on next page)

19

a union’s practice of administering an examination, “ par

tially subjective in nature,” with “ no established [pass/

fail] standard.” 416 F,2d at 136. The Eighth Circuit

thought “ it . . . essential that journeymen’s examinations

be objective in nature [and] that they be designed to test

the ability of the applicant to do that work usually re

quired of a journeyman.” Id.

In reaching this conclusion, we do not necessarily

accept the government’s contention that [the test ad

ministrator], as an individual, would, because of his

past participation in the exclusionary policies of the

Local, discriminate against Negroes in giving and

grading journeymen’s examinations. We are not here

concerned with the individual who gives and grades

the examination. We are concerned rather with the

system, the nature of the examination, its objectivity

and its susceptibility to review.

Id. (emphasis added). In Vogler, the Fifth Circuit also

focused on the effects of subjective criteria. A district

court order requiring a union to develop objective criteria

for membership “ based on industry need” was upheld be

cause subjective criteria—calling for applicants to obtain

recommendations from present members and to receive a

favorable vote of a majority of the membership—caused

the exclusion of blacks. See 407 F.2d at 1049-50, 1054-55.20

(Continued from previous page)

Fair Employment Laws: A General Approach to Objective

Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598 (1969).

See H.R. Rep. No. 238, at 8 n.2; S. Rep. No. 415, at 15 n.1. That

article argued that " [ i ] f any subjective procedure has a sys

tematic effect in disadvantaging blacks, the employer should

be required to show the same justification as for a test or

other objective procedure." 82 Harv. L. Rev. at 1677.

20The other courts that had considered the issue prior to

Congress' enactment of the amendments to Title VII agreed

that disparate impact analysis could be applied to subjective

practices. See United States v. Dillon Supply Co., 429 F.2d 800,

802, 804 (4th Cir. 1970) (district court committed reversible

error by failing to consider that "[p]ractices, policies or pat-

(Continued on next page)

20

Inasmuch as the contemporaneous case law included

not only Griggs, but also lower court decisions applying

§ 703(a) (2) disparate impact analysis to subjective prac

tices, Congress’ express intent in 1972 firmly compels that

application today.

IV. THE ADMINISTRATIVE INTERPRETATION OF

TITLE VII SUPPORTS THE APPLICATION OF

DISPARATE IMPACT ANALYSIS TO SUBJEC

TIVE EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES

Further support for the application of disparate im

pact analysis to subjective practies is found in the adminis

trative regulations concerning Title VII, which have con

sistently required the validation of all selection procedures.

The Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Proce

dures, 29 C.F.R. § 1607 (1986), “ based upon principles

which have been consistently upheld by the courts, the Con

gress, and the agencies,” 43 Fed. Reg. 38290 (1978), con

template application of disparate impact analysis to “ any

selection procedure,” id. at § 1607.3, including “ the full

range of assessment techniques from traditional paper and

pencil tests . . . through informal or casual interviews and

unscored application forms.” Id. at ’§ 1607.16Q. And as

the enforcing agencies’ “ administrative interpretation of

(Continued from previous page)

terns, even though neutral on their face, may operate to seg

regate and classify on the basis of race at least as effectively

as overt racial discrimination" where "the government offered

proof of a decentralized system of hiring and assignment which

vested broad authority on the supervisors of largely segregated

departments and which had no uniform or objective standards

for hiring or assignment"); United States v. Bethlehem Steel

Corp., 446 F.2d 652, 655 (2d Cir. 1971) (finding that "jobs were

made available to whites rather than to blacks" in part because

"[tjhere were no fixed or reasonably objective standards and

procedures for hiring"); Rowe v. General Motors Co., 457 F.2d

348, 355, 359 (5th Cir. 1972) (although employer had no "de

liberate purpose to maintain or continue practices which dis

criminate," court struck down "promotion/transfer procedures

which depend[ed] almost entirely upon the subjective evalua

tion and favorable recommendation of the immediate foreman").

21

the Act,” 21 the Guidelines are “ entitled to great defer

ence.” Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 431; Griggs, 401 U.S. at

433-34; see also Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers’ Interna

tional Association v. EEOC, — U.S. at —, 106 S.Ct. at

3044-45 (Court’s interpretation of Title VII “ confirmed by

the contemporaneous interpretations of . . . both the Jus

tice Department and the EEOC, the two federal agencies

charged with enforcement responsibility.]” ) ; Local No.

93, International Association of Firefighters v. City of

Cleveland, — U.S. —, —, 106 S.Ct, 3063, 3073 (1986) (prof

fered construction of Act supported by EEOC guidelines).

Compare General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125,

141-45 (1976) (EEOC regulations not followed because

they contradicted agency’s earlier positions and were in

consistent with Congress’ plain intent); Espinoza v. Farah

Mfg. Co., 414 U.S. 86, 93-94 (1973) (same).22

21The Guidelines were jointly adopted in 1978 by the De

partment of Justice, as well as the EEOC, the Civil Service Com

mission, and the Department of Labor. 29 C.F.R, § 1607.1A.

Section 713(a) of Title VII authorizes the EEOC "to issue, amend

or rescind suitable procedural regulations to carry out the pro

visions of [the statute]." 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-12(a).

22According to the Uniform Guidelines, a selection pro

cedure having an adverse impact must be validated unless the

employer "choose[s] to utilize alternative selection procedures

in order to eliminate adverse impact." 29 C.F.R. § 1607.6A.

No selection procedures are exempted from this requirement.

The government, however, points out that "[t]here are circum

stances in which a user cannot or need not utilize the valida

tion techniques contemplated by these guidelines," id. at

§1607.68, and asserts that one such circumstance is the use of

"informal or unscored selection procedure[s]." Id. at §1607.6B

(1). The government then concludes that an employer need only

"justify [the] continued use of [such] procedurefs] in accord

with Federal law," id., and that the articulation of a legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reason suffices as the requisite justification.

See Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae at 19-20. This

argument is a distortion of the Guidelines. First, the Guidelines

also include "formal and scored procedures" as circumstances

in which an employer cannot or need not utilize validation

techniques. See id. at §1607.6B(2). Second, the government

(Continued on next page)

22

In requiring applicaton of the disparate impact analy

sis to all selection procedures, the Guidelines track the

now superseded administrative regulations upon which

this Court relied in its affirmation of the disparate im

pact test in Griggs. The EEOC’s 1966 and 1970 Guide

lines,23 which the Court treated “ as [having] express[ed]

(Continued from previous page)

has neglected to mention the first two clauses of § 1607.6B(1),

which provide that an employer using an informal or unscored

procedure should (1) "eliminate the adverse impact," or (2)

"modify the procedure to one which is a formal, scored or

quantified measure." Finally, the government's "belief" that

the use of a selection procedure having a disparate impact may

be justified by the mere articulation of a legitimate, nondiscrim-

inatory reason is undermined by the questions and answers

provided to explain the Guidelines:

36. How can users justify continued use of a pro

cedure on a basis other than validity?

A. Normally, the method of justifying selection pro

cedures with an adverse impact and the method to which

the Guidelines are primarily addressed, is validation. The

method of justification of a procedure by means other than

validity is one to which the Guidelines are not addressed.

See Section 6B. In Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424,

3 FEP Cases 175, the Supreme Court indicated that the bur

den on the user was a heavy one, but that the selection

procedure could be used if there was a "business neces

sity" for its continued use; therefore, the Federal agencies

will consider evidence that a selection procedure is neces

sary for the safe and efficient operation of a business to

justify continued use of a selection procedure.

44 Fed. Reg. 11996, 12002 (1979). Cf. Comment, Applying Dis

parate Impact Theory to Subjective Employee Selection Pro

cedures, 20 Loy. L.A.L. Rev. 375, 389 (1987) ("How to 'other

wise justify' . . . selection procedures remains an open ques

tion."). The government's proposed standard of justification

would flout, rather than "accord" with, the federal law as an

nounced in Griggs.

23The Guidelines on Employment Testing Procedures, issued

in 1966, were not published in the Federal Register. They were

superseded in 1970 by the Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures, published at 35 Fed. Reg. 12333 (1970) (codified

at 29 C.F.R. § 1607, superseded in 1978).

23

the will of Congress,” Griggs, 401 U.S. at 434, interpreted

Title YII to prohibit the use of any “ test” that was dis

criminatory in operation and for which job-r elatedness

could not be established. 35 Fed. Reg. at 12334 (§ 1607.3).

They defined the term “ test” broadly, including within

its scope such subjective practices as “ scored interviews”

and “ interviewers’ rating scales.” Id. at 12334 (§ 1607.2).

Elsewhere, the EEOC Guidelines recognized that “ [s]elec

tion techniques other than tests,” such as unscored “ casual

interviews” and “ application forms,” might also “ have

the effect of discriminating against minority groups.” Id.

at 12336 (§ 1607.13). Under those circumstances, the em

ployer was required to validate the selection technique(s)

at issue or to eliminate the disparate impact. Id.24

V. APPLICATION OF THE DISPARATE IMPACT

ANALYSIS TO SUBJECTIVE PRACTICES FUR

THERS THE PRIMARY PROPHYLACTIC PUR

POSE OF TITLE VII

The application of § 703(a) (2) to subjective practices

is entirely consistent with Title V II ’s central aim of “ elim

inating the effects of discrimination in the workplace.”

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara County,

Calif., — U.S. —, —, 1.07 S.Ct. 1442, 1451 (1987); see also

Teal, 457 U.S. at 449 (“ Congress’ primary purpose was

the prophylactic one of achieving equality of employment

‘ opportunities’ and removing ‘ barriers’ to such equal

ity.” ). It is also consistent with the statute’s goal of en

24The Department of Labor, in its interpretation of Execu

tive Order 11246, 33 Fed. Reg. 14392 (1968) (Employment Tests

by Contractors and Subcontractors: Validation), similarly con

templated the validation of "any . . . performance measure used

to judge qualifications for hire, transfer or promotion," includ

ing measures of "intelligence," "ability," "aptitudes," "knowl

edge and proficiency," as well as measures of "personality or

temperament," id. at 14393 (§ 9). See id. at 14392 (§ 1(g)). Not

ing that "[sjelection techniques other than tests may also be im

properly used so as to have the effect of discriminating," the

Department required that such techniques as "unscorec! inter

views" and "unscored application forms" also be validated or

adjusted to eliminate any disparate impact. Id. at 14393 (§ 10).

24

couraging employers to engage in voluntary self-examina

tion of their employment practices, and will not unneces

sarily or unreasonably diminish management preroga

tives.

A. Title VII “ Prohibits All Pactices in Whatever

Form Which Create Inequality in Employment

Opportunity’ ’

While § 703(a) (2 ) ’s broad proscription of discrimina

tion in employment extends to all “ practices, procedures,

or tests neutral on their face, and even neutral in terms

of intent . . . that operate as ‘ built-in headwinds’ for mi

nority groups and are unrelated to measuring job capa

bility,” Griggs, 401 U.S. at 430, 432 (emphasis added),

the government would have plaintiffs prove intent in all

challenges to subjective employment practices.

However, irrespective of an employer’s good inten

tions, the use of subjective selection criteria may unfairly

restrict employment opportunities for minorities and wom

en. Subjective criteria leave substantial room for deeply

ingrained, unconscious biases. As one commentator has

written: “ A supervisor [who is] judging a subordinate

for promotion potential tends to look for traits [in the

subordinate] which the supervisor feels he himself has. It

is, of course, much easier for a Caucasian male to find such

traits in other Caucasian males than in minorities and

women.” Stacy, Subjective Criteria in Employment De

cisions Under Title VII, 10 Ga. L . Rev. 737, 739 (1976).

See also B. Plumbley, Recruitment and Selection 145-46

(1981) (When a candidate’s background and personality

“ appear to have been similar to his, the interviewer is

presupposed to be biased in favour of him. . . . Judgment

can be warped in this way without the interviewer being-

conscious of it.” ).25 Moreover, the criteria themselves may

25See, e.g., Wilmore v. City of Wilmington, 699 F.2d 667,

673-74 (3d Cir. 1983) (exclusion of blacks from administrative

jobs a result of both conscious and unconscious biases); Chance

v. Bd. of Examiners, 330 F.Supp. 203, 223 (S.D.N.Y. 1971) (white

interviewers may have unconsciously discriminated against

blacks and Flispanics), af'd 458 F,2d 1167 (2d Cir. 1972).

25

be “ unrelated to measuring job capability.” Griggs, 401

U.S. 432; see D. Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical Proof of Dis

crimination §1.23, at 27 (1986 Supp.) (“ [T]he defendant

[may be] unbiased in evaluating the candidates and . . .

the disparate impact [may be] caused by differences in

characteristics of the candidates which, if measured ob

jectively, would surely trigger a demand for proof of job

relatedness.” ).26 The Court has made precisely this point

with respect to subjective performance appraisals put

forth by the employer in Albemarle in an attempt to vali

date the objective test at issue there. The Court rejected

the proffered correlation, however, because the “ super

visors [had been] asked to rank employees by a ‘ standard’

that was extremely vague and fatally open to divergent

interpretations.” 422 U.S. at 433. The Court had no way

of knowing “ whether the criteria actually considered were

sufficiently related to the Company’s legitimate interest

in job-specific ability to justify [the] testing system.”

Id. (emphasis in original).27 Thus, the Court was rightly

concerned that the subjective performance appraisals may

not have measured job-related skills.

In order to achieve Congress’ primary purpose of

“ achieving equality of employment ‘ opportunities’ and

removing ‘ barriers’ to such equality,” Teal, 457 U.S. at

449, the disparate impact analysis must be applied to all

employment practices, both objective and subjective.

26See, e.g., Hawkins v. Bounds, 752 F.2d 500, 504 (10th Cir.

1985) ("The record in this case contains no evidence . . . that

the practice of totally discretionary detailing or its use in the

promotion procedure [was] required by business necessity.");

Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249, 1288 (D.C. Cir. 1984) (defendant

never even attempted to showing job-relatedness of subjective

experience requirement), cert, denied, 471 U.S. 1115 (1985);

Greenspan v Automobile Club, 495 F.Supp. 1021, 1033 (E.D.

Mich. 1980) (defendant failed to base evaluations on job analy

sis).

27Cf. B. Schlei & P. Grossman, Employment Discrimination

Law 203 (2d ed. 1983) (. . . [T]he evaluative devise [should have]

fixed content and calif] for discrete judgments.").

26

B. Title VII Requires That Employers “ Self-Exam-

ine and Self-Evaluate Their Employment Prac

tices”

The government’s apparent concern for management

prerogatives cannot obscure the fact that the exclusion of

subjective criteria from disparate impact analysis would

allow and even encourage employers to avoid the intro

spective assessment of their employment practices as con

templated by Title VII. Provided a convenient sanctuary

in subjective criteria, employers would be loathe “ ‘ to self

examine and to self-evaluate their employment practices

and to endeavor to eliminate . . . the last vestiges of an

unfortunate and ignominious page in this country’s his

tory.’ ” Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 418 (quoting United States

v. N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354, 379 (8th Cir. 1973)). Cf.

United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. at 204 (Title VII

“ intended as a spur or catalyst” for employer efforts to

eliminate effects of discrimination).

Rather than encourage self-examination, the govern

ment’s proposed exemption for subjective practices would

likely encourage blind adherence to those practices. See

Griffin v. Carlin, 755 F.2d 1516, 1525 (11th Cir. 1985)

(“ Exclusion of . . . subjective practices from the reach

of the disparate impact model of analysis is likely to en

courage employers to use subjective, rather than objec

tive, selection criteria.” ) ; D. Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical

Proof of Discrimination §1.23, at 27 (1986 Supp.) (“ ex

clusion of subjective criteria from review under the dispa

rate impact model may encourage employers to rely less

on objective criteria and more on general standards” ).

Indeed, to avoid the potential for disparate impact lia

bility, employers would be inclined simply to consider ob

jective criteria, such as a diploma requirement, within the

context of a subjective interview. Yet “ [i] t could not

have been the intent of Congress to provide employers

with an incentive to use such devices rather than validated

objective criteria.” Griffin v. Carlin, 755 F.2d at 1525;