Draft Memorandum by Alfieri

Working File

January 1, 1982 - January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Draft Memorandum by Alfieri, 1982. ebb43893-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7c6c2d59-f5af-4a0c-9f43-0f335898f3d3/draft-memorandum-by-alfieri. Accessed February 02, 2026.

Copied!

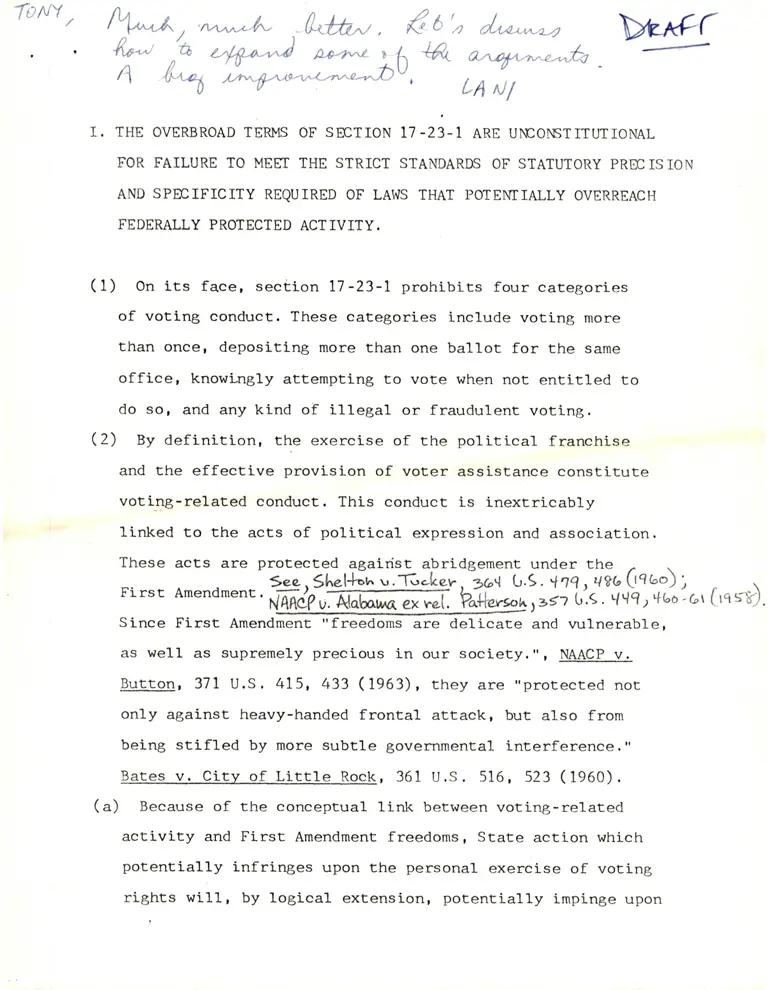

TttNY,,/ h-^^,1', 'wrn^,"/n- Ca&, , & 6',, ,/.*,*o,

l\o.*' "e ""/f*^) ,--,r^, 1 A 1A" aan/-a-.u-t,-,nfc

_A ha ;f^*-^ ',"'.bU, LA A//

Dkjdc(

I. THE OVERBROAD TERI'IS OF SECTION L7.23-I ARE UI\COIISTITUTIONAL

FOR FAILURE TO },IEE[ THE STRICT STANDARDS OF STATUTORY PRECISION

AND SPECIFICITY REQUIRED OF LAWS THAT POTENIIALLY OVERREACH

FEDERALLY PROTECTED ACT]VITY.

(1) On its face, seciion 77-23-7 prohibits four earegories

of vottng conduct. These categories include voting more

than once, depositlng more than one ba11ot for the same

office, knowi-ngly attempting to vote when not entitled to

do sor and any kind of i1lega1 or fraudulent voting.

(Z) By definition, t!" exercise of the political franchise

and the effective provision of voter assistance constitute

voting-related conduct. This conduct is inext.ricably

linked to the acts of political expression and association.

These acts are protecced agalrist abridgernent under the ? \

Firsr Amen )ee,Shel-l-u. r.,.Tr.Lev , gGq L.9. { ,t1 ,\t9.gq(r:) ;dment -rr)'

Lig' {qh ,4uolc'r (rqs$'

Since First Amendment "freedoms are delicate and vulnerable,

as well as supremely precious in our socieEy.", NAACP v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415, 433 ( 1963), they are ',prorecred nor

only against heavy-handed frontal attackr but also from

being stifled by more subtle governmental interferenee."

Bates v. City of Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516, 523 (tq0O).

(a) Because of the conceptual link between voting-related

activity and First Arnendment f reedorns, State aetion which

potentially infringes upon the personal exercise of voting

rights wi11, by logical extension, potentially impinge upon

2

the individuar enjoyrnent of First Amendment freedoms. This

potential incursion violates the fundamental axiorn that

"regulatory measures ... no matter how sophisticated,

cannot be employed in purpose or in effect to stifle,

penallze, or curb the exercise of First Arnendment rights."

Loutsiana ex re1. Grenilliql_y_,__MAg!, 366 U.S. 293, 297 (1961)

(U) Because "(b)road prophylactic n:1es" in the First Amendment

area are "suspect", "government may regulate in the area

only with narrow specificity.'r Button, 371 U.S. at 438,

433 (citrations omirted) ,/dfua-lx ef YedLq,-#Eta

*leYtse.,

A@n#*ffit&ile^ t b*'l,,statutes abuttin8 upon Firs t Arnendrnent

freedoms 'rtntJst be drawn with 'precision' and m.rst be narrowly

'tailored' to serve their legitimate obJectives." D:nn v.

Blgmsrein, 405 U.S. 330, 343.,.(lgl2)(cirations omitred) .

. precision of ree,rhti." *h&*#f,3..,r"" srarures AM,*u

borderrhq oh

^Y.oeGfuBr protected spheres of First Arnendment libercy "evoke

constitutional doubts of the utrnost gravity. " ShuttlesworEh

y. Citv of Birmineha8, 382 U.S. 87, 91 (1965). These doubts

largely coneerrr the constitutional vice of statutory over-

breadth. This vice is "inherent in a penal statute

which does not aim speciflcally at evils within the allorvable

area of State control,but, on the contrary, sweeps within

its ambit other activities that in ordinary circurnstances

constitute an exercise of ..." First Amendment liberty.

Thorrlh:lll v. Alabama, 310 U.S , 88, 97 -98 ( 1939) .

(3) Section l7-23-L is a penal statute directed at rhe "evil',

of voter fraud. It is settled that "the prevention of such

fraud is a legitimate and compelling government goaI." Dunn,

405 U.S. at 345. The legitimacy of this goal derives from

the importance of preserving the "integrity" of the State

elecroral process.'Cousins v. Wigod_a, 419 u.s. 477 , 491 ( 197 5)

Arguably, the State of Alabama, in prorm:lgating section 17 -

23-1, ft&y have undertaken to serf/e this valid sovereign

interesE. If.so, it has failed decisively.

(a) Section 17 -23-L fails properly to advance Alabarna's

legitimate State interest because its literal terms are

instinct with tfre d.,botent,iaI-{,r for reaching and punishing

protected First AmednmenE conduct. Courts will condemn a

statute as "impermissibly overbroad if it permits punish-

ment of activity fairly within the protection of the United

States Constitution." Florida Businessmen for Free Enterprise

v. State of Florida, 499 F. Supp, 346, 353 (lt.p. F1a. 1980),

aff 'd 673 F.2d 1213 ( lltfr Cir. 1982).

(u) Section Ll -23-l is insrincr with rhe ,porenrial*'for

overreaching beeause its general language is neither precise

nor speelfic. This dual structural flaw is best illustrated

by the phrase "i1lega1 or fraudulent voting". On its face,

this phrase contains two operative termsr i11ega1 and fraudu-

1ent. Although these terms represent core statutory eoncepts,

section 17 -23-l fails to infuse them with meaningful substan-

tive content. Their undefined quality gives rise to the

prciblem of overbreadth. -

4

(c) section 17-23-l suffers from real and substantial over-

breadth. This overbreadth is demonstrated in two distinct

ways' First, the statute is substantially overbroad because

basic First Amendment activities are open to eonstmction

as "i11ega1 or' fraudulent" voting-related conduct. Since

these aetrvities encompass an infinite variety of private

as well as public forms of expression and association, the

statute's potential for impermissible application is virtually

Ltnbounded. Second, the statute is substantially overbroad

because its criminal "penalty,, is significant in regard to

severity of punishmenr ("q,i^pr-igon*nnt ir. a- parnitot^*igr1 &r -^rt

New york v. Ferber, 50 r'*:rl*i^#;,T6#?;y:#",)fr:;)..

(d) Furthermore, section 17 -23-1 is fatally overbroad because

less drastic alternative means of promoting Alabama,s State

interest exist. "rf the state has open to it a less drastic

way of satisfying its legitimate interests, it may not choose

a legislative scheme that broadly stifles the exerclse of

fundarnental personal liberties.', @ , 4!4

u's' 51 ' 59 (1973). Accordr Aladdin's_cast1e, rnc. v. city

of }"lesquire, 630 F.2d lOZg, 1038 n. 13 ( Stfr C ir. 19g0) r Reeves

v. l"tcConn, 631 F.2d 377, 3g3 (5th Cir. 1980); @

of opel0usas, 659 F.2d 1065, 1071 (5trr cir. 1gg1). A less

drastic alternative means is available in a more artfullv

speci{-r'caily r-,nlo,*^{\, Idrawn statute aimed at a narrow range of sb6btf*a{voting_ -

related conduct exclusive of essentially innocent expression

and association.

(4) Section t7 -23-1's 4potentiaL&. impact on protected spheres

of expression and association creates the danger of First

Amendment chilling effect. Appreciation of the "chi11,' on

primary conduct caused by "toleratirg, in the area of First

Arnendment freedoms, the existence of a penal statute suscep-

tible of sweeping and improper application.", Button, 371

U.S. at 433, lies at the heart of the overbreadth doctrine.

Hobbs v. Thompson, 448 F.2d 456, 460 (5th Cir. 1971). See

also, leFlorq v. Robinson, 434 F.2d 933, 936 (5th Cir. 1970).

Courts have long recognized that "1avJS which are overbroad

tend to 'chi1l' the exercise of important First Amendment

rights". Purple Onion, I!g. v. Jaekson, 511 F. Supp , 1207,

L219 (N.D. Ga. 1982).

(a) Sect,ion t7 -23-l Benerates a chilling effect because it

hangs , like .the Sword of Darnocles, over the heads of voters

as well as individuals engaged in voter assistance, threaten-

ing them with prosection and punishment if they participate

in 1awfu1 Ffrst Amendment aetivities. Since the mere threat

of statute-based sanctions may deter the exercise of First

Amendment rights "almost as potently as the actual applica-

tion of sanctions.", Button, 377 U.S. at 433, the chilling

effect generated by the threat of prosecution and punishment

,r.ro"r{ao"tube cannot be gainsaid.

o{^t) A.Vd Si€aCY?$odEb A?t*ye}.dglr1r1(ax(-,Plqf. eges'ttrod sffiL-sn

oycrtlh:eedcls.

( 5) The State courts of Alabama have not constn:ed section

17 -23-t so as ro cure g.t^:!"J.til|f,-o""r. inrirmiry or

overbreadth. In fact, the Alabama courts have left the

stacuters key provision wholly intact (i.e. "illegal or

fraudulent, voting"). The full extent of their constrLrction

amounts to .the facile observation that courts, where inter-

preting the phrase "i11ega1 or fraudulent voting", "rnay rely

on the remainder of the statute to provide a clear statement

of what condqct is proscribed." tr{ilder_v. State, 401 So.2d

151 , 160 (efa. Crim.App.), cert. depr.ed,401-So.2d L67

(eta. legl) , cerE. denied , 4s4 u.s . ,*z1lllJ,lJ""., rhe

remainder of the statute does not provide a "cLear statement'r

of prohibited eonducE. The absence of such a statement is

attributable to the uncertain mens rea element embedded in

the statute. This scienter-based uncertainty stems both

from the inconsistent use of language in the body of the

the statute and from the ambiguous results'of the Alabama

Supreme Court's historical efforts to constnre the statute.

See, e.B. , I,lilson v. $tate, 52 A1a. 299 ( 1aZ S;; Gordon v.

State, 52 Ala. 308 ( 1AZ S; . This uncertainty persists because

recent Alabama courE decisions have failed to determine

whether or not a scienter requirement may be generally

implied under the circumstances of voting. See, €.A. r

Bozeman v. State, 401 So.2d 167 (Rta. Crim. App.), cert.

denied, 401 So.2d 171 (ara. 1981), cerr._denied, 454 U.S.

1058 (1982); lrlilder v. State, 401 So.2d 151 (efa. Crim. App.),

cerc. denied, 401 So.2d t67 (efa. 1981), cert. d-enied, 454

u.s . 1057 ( 1982) .

(6) Because the First Amendment rightd of political expression

and association are intimately tied to the exercise of the

political franchise and to the extension of voter, assistance'

fivs+ O-erdr,er.t

secgion l7 -23-L is susceptibl! of application to fituWv&,

freedoms. This susceptibility is a form of statutory authori-

zatlon enabllng the State of Alabama to punish, by criminaL

sanction, eonstitutionally protected activity. The potential

for punishrnent under section L7--23-l poses' a real and sub-

stantial threat to the free exercise of political expression

and association. Since the threat of punishment fflA cause,

individuals to refrain from engaging in politieal acts of

expression and association, section t7'23-l e@ operate,

to chil1 the exercise of vital First Amendment rights.*

of frr/.iowt?-??- |

Because^this statute-induced chilling effect, twd*Wt@

is impermissibly overbroad and therefore invalid on its face.

v. l,l/ilsoh , 4os U'S ' {tstszr (rz) '