Hillegas v. Sams Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hillegas v. Sams Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1965. eee0833c-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7d1521da-44f1-4548-884d-fffee4298877/hillegas-v-sams-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

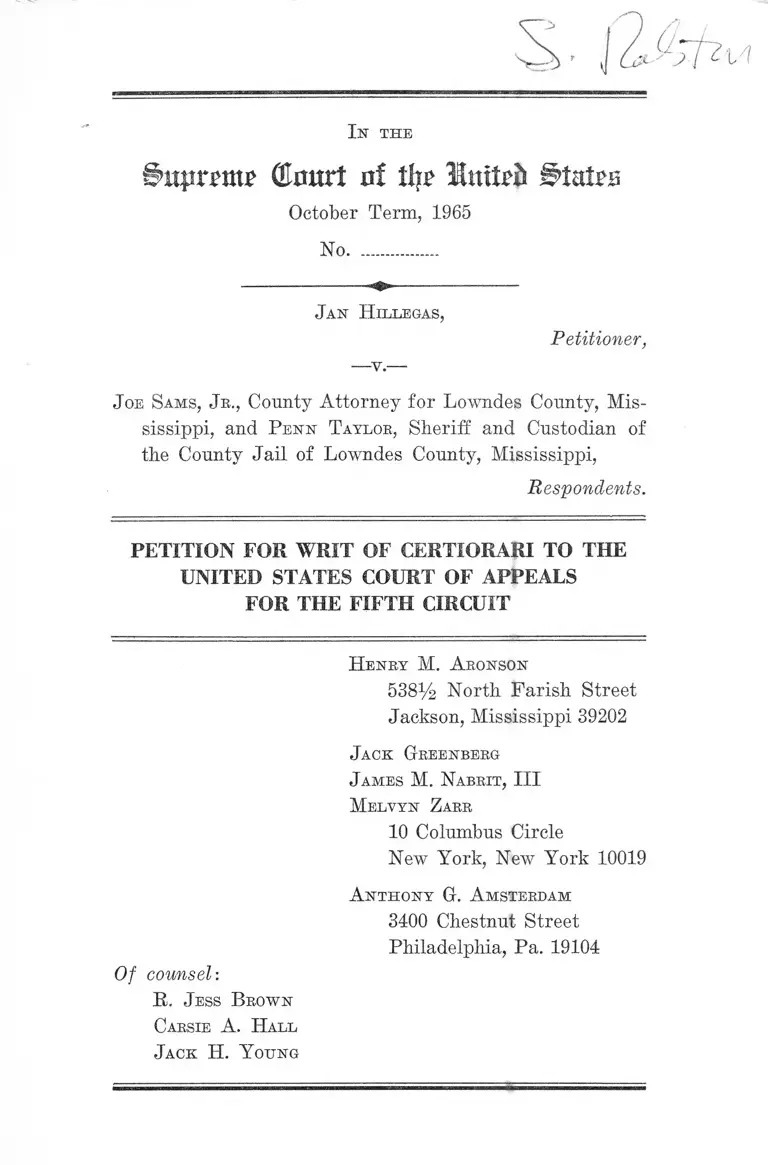

I n t h e

§>ujirm£ CUnurt of tlu Inttofu

October Term, 1965

No................

J an H illegas,

—v.—

Petitioner,

J oe Sams, J b., County Attorney for Lowndes County, Mis

sissippi, and P enn Taylor, Sheriff and Custodian of

the County Jail of Lowndes County, Mississippi,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

H enry M. A ronson

538^2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabbit, III

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Anthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Of counsel:

R. J ess Brown

Carsie A. H all

J ack H. Y oung

I N D E X

Citations to Opinions Below ....................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................. ..................................... . 2

Question Presented ....................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved...... 3

Statement ......................... 5

Reasons for Granting the Writ ..................... 9

I. The Case Presents an Important Issue Respect

ing the Federal Judicial Power and Obligation

to Protect Civil Rights, Not Heretofore Decided

by This Court .................................... 9

II. The Decision Below Is Wrong and Seriously Im

pairs Federal Judicial Power to Protect Na

tional Civil Rights .............................................. 14

A. Federal Habeas Corpus Courts Are Empow

ered to Discharge From Mesne Restraints

Petitioners Held to Answer Unconstitutional

State Prosecutions ........................................ 14

B. Petitioner’s Prosecution Is Unconstitutional 14

PAGE

n

C. A Federal Habeas Corpus Applicant in Peti

tioner’s Situation Is Not Required to Ex

haust State Judicial Remedies ..................... 17

(1) Wyckoff, Brown v. Bayfield and 28

U. S. C. §2254 ................... 18

(2) Legislative History ................................ 23

(3) Judicial Development of the Exhaustion

Doctrine .................................................. 40

(4) Application of the Exhaustion Doctrine

to Civil Rights Cases ...... ........ 45

(5) Application of the Exhaustion Doctrine

to Cases Involving Federal Voting

Rights ..................................................... 53

Conclusion................................................................................. 58

Appendices ................................................................................ l a

A ppendix I—

Order of the District Court................................... la

Appendix II—

Opinion and Judgment of the Court of Appeals .... 2a

Appendix III—

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus...... ............... 15a

PAGE

H I

Table of Cases

page

Anderson v. Elliott, 101 Fed. 609 (4th Cir. 1900),

dism’d 22 S. Ct. 930 (1902) ............. .......................... 55

Application of Wyckoff, 196 F. Snpp. 515 (S. D. Miss.

1961), 6 Race Rel. L. Rep. 786 ..........8, 9,17,18, 20, 22, 44

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964) ..............11, 48, 51

Baker v. Grice, 169 U. S. 284 (1898) ....... .................... 14, 43

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963) .... 50

Barr v. Columbia, 378 U. S. 146 (1964) ..................... 16

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516 (1960) ................. 15

Birsch v. Tumbleson, 31 F. 2d 811 (4th Cir. 1929) ___ 55

Bouie v. Columbia, 378 IT. S. 347 (1964) .................. 17

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel.

Virginia State Bar, 377 U. S. 1 (1964) ..................... 15

Brown v. Cain, 56 F. Supp. 56 (E. D. Pa. 1944) .......... 55

Brown v. Rayfield, 320 F. 2d 96 (5th Cir. 1963), cert.

denied, 375 TJ. S. 902 (1963) ........ 8, 9,17,18,19, 21, 22, 44

Bushell’s Case, Vaughan, 6 How. St. Tr. 999, 124 Eng.

Rep. 1006 (1670) .................................... .................... 24

Castle v. Lewis, 254 Fed. 917 (8th Cir. 1918) .......... 55

Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 IT. S. 445 (1927) .......... 16

Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheat. 264 (1821) ..................37, 46

Cook v. Hart, 146 U. S. 183 (1892) ......................... 14, 22

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1 (1958) ................... ...... . 49

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 IT. S. 536 ........... ....................... 15

Cox v. Louisiana, 348 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1965) ....10, 48, 50

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 IT. S. 278

(1961) .............. ...................... ................................ . 50

Cunningham v. Skiriotes, 101 F. 2d 635 (5th Cir. 1939) 43

i y

Darr v. Burford, 339 U. S. 200 (1950) ........................ 22

IJi[worth v. Riner, 343 F. 2d 226 (5th Cir, 1965) ....—10, 50

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965) ...... 10,12,16,

48, 50

PAGE

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943) —11,12

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) —15,51

England v. Louisiana State Board of Medical Exam

iners, 375 U. S. 411 (1964) ....................................... 52

Ex parte Ah Lit, 26 Fed. 512 (D. Ore. 1886) .............. 42

Ex parte Bartlett, 197 Fed. 98 (E. D. Wise. 1912) ...... 43

Ex parte Bollman, 4 Cranch 75 (1807) ....... ................. 24

Ex parte Bridges, 4 Fed. Cas. 98, No. 1,862 (C. C. N. D.

Ga. 1875) .................................................................... 41

Ex parte Conway, 48 Fed. 77 (C. C. D. S. C. 1891) .... 56

Ex parte Hawk, 321 U. S. 114 (1944) ........................ 22,44

Ex parte Lange, 18 Wall. 163 (1873) ............................ 24

Ex parte McCardle, 6 Wall. 318 (1867) ........................ 41

Ex parte McCready, 15 Fed. Cas. 1345, No. 8,732

(C. C. E. D. Va. 1874) .......... ............................. ...... 41

Ex parte Royall, 117 IJ. S. 241 (1886) ...... 11,14, 22, 42, 43,

44, 45, 46, 49, 53

Ex parte Tatem, 23 Fed. Cas. 708, No. 13,759 (E. D.

Va. 1887) ..... .............................................................. 41

Ex parte Tilden, 218 Fed. 920 (D. Ida. 1914) .............. 55

Ex parte United States ex rel. Anderson, 67 F. Supp.

374 (S. D. Fla. 1946) .............................................. 55

Ex parte Warner, 21 F. 2d 542 (N. D. Okla. 1927) ...... 55

Ex parte Watkins, 3 Pet. 193 (1830) ............................ 24

Ex parte Wood, 155 Fed. 190 (C. C. W. D. N. C. 1907) .. 56

y

Farmer v. State, 161 So. 2d 159 (Miss. 1964) ______ 51

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 (1963) .....12,13, 25, 26, 28, 40, 48

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951) ................. 52

Fields v. Fairfield, 375 U. S. 248 (1963) ..................... 16

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963) ........ ..15, 51

Flynn v. Fuellhart, 106 Fed. 911 (C. C. W. D. Pa. 1901) 55

Garner v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 157 (1963) ...... ......... 16

Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 64 (1964) .............. 50

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigating Committee,

372 U. S. 539 (1963) .................................................. 15

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U. S. 218 (1964) ................................... 49

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 (1939) ........................ 15, 45

Henry v. Eock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964) ................ 15,51

Hunter v. Wood, 209 IT. S. 205 (1908) ..................... 14, 56

In re Alexander, 84 Fed. 633 (W. D. N. C. 1898) ..... 43

In re Fair, 100 Fed. 149 (C. C. D. Neb. 1900) ............ 54

In re Lee Sing, 43 Fed. 359 (C. C. N. D. Cal. 1890) .... 44

In re Lee Tong, 18 Fed. 253 (D. Ore. 1883) ........... 42

In re Loney, 134 U. S. 372 (1890) .....................14, 55, 56, 57

In re Matthews, 122 Fed. 248 (E. D. Ky. 1902) .... 55

In re Miller, 42 Fed. 307 (E. D. S. C. 1890) ........... 55

In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1 (1890) .............. .......14, 25, 27, 53,

54, 55, 56, 57

In re Parrott, 1 Fed. 481 (C. C. D. Cal. 1880) ....... 42

In re Quong Woo, 13 Fed. 229 (C. C. L>. Cal. 1882) ..... 42

In re Sam Kee, 31 Fed. 680 (C. C. N. D. Cal. 1887) .... 44

In re Tie Loy, 26 Fed. 611 (C. C. D. Cal. 1886) ... 42

In re Wan Yin, 22 Fed. 701 (D. Ore. 1885) .......... 42

PAGE

VI

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458 (1938) ..................... 24

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906) ..................... 11

Knight v. State, 161 So, 2d 521 (Miss. 1964) .......... 51

Lima v. Lawler, 63 F. Supp. 446 (E. D. Va. 1945) ...... 55

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 (1963) .............. 16

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 (1963)

39, 48

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 TJ. S. 501 (1946) ..................... 50

Minnesota v. Brundage, 180 U. S. 499 (1901) ______ 43

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961) .........................39, 48

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U. S. 103 (1935) ..................... 44

Moss v. Glenn, 189 U. S. 506 (1903) ...... ..................... 22

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958) .............. 15

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) .......... 15,17, 50

New York v. Eno, 155 U. S. 89 (1894) ...................... . 22

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254 (1964) .. 50

Ohio v. Thomas, 173 U. S. 276 (1899) ........................ 54

Peacock v. City of Greenwood, 347 F. 2d 679 (5th Cir.

1965) ........................................................................... 48

People v. McLeod, 25 Wend. 482 (Sup. Ct. N. Y.

1841) ........ ................................................... ............. 26,27

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 (1963) .......... . 16

Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U. S. 158 (1944) ...... 50

Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F. 2d 336 (5th Cir. 1965), cert.

granted, 34 U. S. L. W. 3101 (10/11/65) ..............12,48

Eeed v. Madden, 87 F. 2d 846 (8th Cir. 1937) .............. 54

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153 (1964) ................ . 16

PAGE

V ll

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 (1948) ........ 50

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 (1960) ..................... 15

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 (1959) ................. 50

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 (1958) .......... .............. 15

Thomas v. Collins, 323 IT. S. 516 (1945) ................... 15

Thomas v. Mississippi, 380 IT. S. 524 (1965) ......... ...... 51

Thomas v. State, 160 So. 2d 657 (Miss. 1964) ........... 51

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 (1960) ..... ........ 16

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963) ..................48,53

PAGE

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 (1941) .......... 15

United States v. Hamilton, 3 Dali. 17 (U. S. 1795) .... 24

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 IT. S. 81

(1921) .................. 16,17

United States ex rel. Drury v. Lewis, 200 U. S. 1

(1906) ...... - ........................... ........................13,14, 22, 55

United States ex rel. Kennedy v. Tyler, 269 U. S. 13

(1925) ........ 55

United States v. Lipsett, 156 Fed. 65 (W. D. Mich.

1907) ............................................................ 55

United States v. Mississippi, 229 F. Supp. 925 (S. D.

Miss. 1964), rev’d, 380 U, S. 128 (1965) ................. 5

United States v. National Dairy Products Co., 372 U. S.

29 (1963) ..................... 17

United States v. Haines, 362 U. S. 17 (1960) .............. 15

United States ex rel. Silverman v. Fiscus, 42 Fed. 395

(W. D. Pa. 1890) ......................................................... 43

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961),

cert, denied, 369 U. S. 850 (1962) ............................ 57

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 (1880) 11

V1U

West Virginia v. Laing, 133 Fed. 887 (4th Cir. 1904) .... 55

Whitten v. Tomlinson, 160 U. S. 231 (1895) ..............14,22

Wildenhus’s Case, 120 U. S. 1 (1887) .................— 14,55

Wo Lee v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ..... 44

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) ................... 17

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ..................... 44

Statutes

Act of September 24, 1789, ch. 20, §14, 1 Stat. 73 ....23, 25, 37

Act of February 13, 1801, ch. 4, §11, 2 Stat. 89 .... 37

Act of March 8, 1802, ch. 8, 2 Stat. 132......................... 37

Act of February 4,1815, ch. 21, §8, 3 Stat. 195.............. 37

Act of March 3, 1815, ch. 43, §6, 3 Stat. 231................. 37

Act of March 2,1833, ch. 57, 4 Stat. 632 ................. 23, 25, 37

Act of August 29, 1842, eh. 257, 5 Stat. 539 ................. 23, 26

Act of March 3,1863, ch. 81, §5, 12 Stat. 755 ................. 38

Act of March 7, 1864, ch. 20, §9, 13 Stat. 14 .................. 38

Act of June 30, 1864, ch. 173, §50, 13 Stat. 223 ......,....... 38

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §3, 14 Stat. 27 .......30, 38, 39, 47

Act of May 11, 1866, ch. 80, 14 Stat. 46 ................. 33, 34, 38

Act of July 13,1866, ch. 184,14 Stat. 98........................ 38

Act of July 16, 1866, ch. 200, 14 Stat. 173..................... 29

Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 28, 14 Stat. 385 ....23, 27, 30, 33

Act of March 27, 1868, ch. 34, §2, 15 Stat. 4 4 .............. 41

PAGE

PAGE

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§8, 18, 16 Stat. 140, 142,

144 ....................................................................... ........

Act of February 28, 1871, ch. 99, §16, 16 Stat. 438 ....38,

Act of April 20, 1871, ch. 22, §1, 17 Stat. 13 ..............

Act of March 1, 1875, ch. 114, §3, 18 Stat, 335 ..........

Act of March 3, 1875, ch. 137, 18 Stat. 470 ................. 37,

28 IT. S. C. §1343 (1958) .......................... .......... 11, 38,

28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958) .................................... 11, 30,

28 U. S. C. §2241 (1958) .......................................... 23,

28 IT. S. C. §2241(c)(2) (1958) .................................

28 IT. S. C. §2241(c) (3) (1958) ................. 9,14,27,40,

28 IT. S. C. §2251 (1958) ....... .... ............................... .

28 IT. S. C. §2253 (1958) ............................ ...............

28 U. S. C. §2254 (1958) ............. ........................19, 20,

42 IT. S. C. §1983 (1958) .............................. 5,16,

42 U. S. C. §1985 (1958) ............................................ 5,

42 IT. S. C. A. §1971 (1964) ............................ 5,16, 56,

Miss. Const, art. 8, §§201, 205, 207 .................. .............

Miss. Const, art. 10, §225 ...... .......... .......... ..................

Miss. Const, art. 12, §§241-A, 244 .................................

Miss. Code Ann. §2666(c) ................................... 4,14,16,

Miss. Code Ann. §§2056(7), 2339, 4065.3 .....................

Miss. Laws, 1st Extra. Sess. 1962, chs. 4, 9, 16, 20

39

39

38

39

39

45

47

54

54

54

28

21

22

38

16

57

16

16

16

17

16

16

X

Other A uthorities

page

Amsterdam, Criminal Prosecutions Affecting Federally

Guaranteed Civil Eights: Federal Bemoval and

Habeas Corpus Jurisdiction to Abort State Court

Trial, 113 U. Pa. L. Bev. 793 (1965) .....................10, 21

IY Bacon’s Abridgment (Philadelphia 1844) .............. 24

3 Blackstone, Commentaries (6th ed., Dublin, 1775) ....24, 25

Brennan, Federal Habeas Corpus and State Prisoners:

An Exercise in Federalism, 7 Utah L. Bev. 423

(1961) ....................................................................... 25,40

Chafee, How Human Bights Got Into the Constitution

(1952) ...... 25

3 Comyns, Digest of the Laws of England (1785) ___ 23

Cong. Debates, vol. 9, Pt. 1 ....................................... 26

Cong. Globe, 27th Cong., 2d Sess.t ................................... 27

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.......................29, 34, 38, 39

Dunning, Essays on the Civil War and Beconstruc-

tion (1898) .................................................................. 38

Frankfurter & Landis, The Business of the Supreme

Court (1928) ......................................................... 39

2 Hale, Pleas of the Crown (1st American ed. Phila

delphia, 1847) .......................................................... 23

Hart, Foreword, The Supreme Court, 1958 Term, 73

Harv. L. Bev. 84 (1959) ............................................ 25

Hart & Wechsler, The Federal Courts and the Federal

System (1954) .......................................................... 37

XL

PAGE

9 Holdsworth, A History of English Law (1926) ....24,25

H. E. 3214, 80th Cong., 2d Sess. (1948) .......... .......... 21

1 Morison & Commager, Growth of the American Re

public (4th ed. 1950) ................................................26, 37

Note, Federal Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners:

The Isolation Principle, 39 N. Y. U. L. Eev. 78

(1964) ......................................................................... 25

Note, The Freedom Writ—The Expanding Use of Fed

eral Habeas Corpus, 61 Harv. L. Rev. 657 (1948) .... 25

Note, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) ......................... . 16

Oaks, Habeas Corpus in the States, 32 U. Chi. L. Rev.

243 (1965) .................................................................... 24

Reitz, Federal Habeas Corpus: Impact of an Abortive

State Proceeding, 74 Harv. L. Rev. 1315 (1961) ...... 25

Reitz, Federal Habeas Corpus: Postconviction Remedy

for State Prisoners, 108 U. Pa. L. Rev. 461 (1960) .... 25

Report of the Seventh Annual Meeting of the American

Bar Association (1884) ................................. ........... . 42

Sen. Rep. No. 1559, 80th Cong. 2d Sess. (1948) .......... 21

Thompson, Abuses of the Writ of Habeas Corpus, 18

Am. L. Rev. 1 (1884) ............................................... . 24

1 Warren, The Supreme Court in United States His

tory (Rev. ed. 1932) .................................................... 37

Wechsler, Federal Jurisdiction and the Revision of

the Judicial Code, 13 Law & Contemp. Prob. 216

(1948) ....... 48

I n t h e

( t o r t o f % Bitmtrfr S ta irs

October Term, 1965

No................

J an H illegas,

Petitioner,

J oe Sams, J r., County Attorney for Lowndes County, Mis

sissippi, and P enn T aylor, Sheriff and Custodian of

the County Jail of Lowndes County, Mississippi,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit entered August 16, 1965, rehearing of

which was denied September 27, 1965.

Citations to Opinions Below

The order of the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Mississippi denying petitioner’s ap

plication for a writ of habeas corpus is unreported and is

set forth in Appendix I hereto, p. la infra. The opinion

of the majority of the Court of Appeals, affirming the order

2

of the district court, and the special concurring opinion of

Circuit Judge Brown are reported at 349 F. 2d 859, and are

set forth in Appendix II hereto, pp. 2a-lla infra. No

opinion was written on denial of petition for rehearing.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered Au

gust 16, 1965, p. 2a infra. Timely petition for rehearing

was denied September 27, 1965, p. 14a infra. The juris

diction of this Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. § 1254(1)

(1958).

Question Presented

Petitioner, a civil rights worker, was arrested in the

Lowndes County, Mississippi courthouse, where she was

assisting Negroes to register to vote. She was thereafter

charged with vagrancy. Prior to her state trial, she peti

tioned the United States District Court for a writ of habeas

corpus, alleging that the Mississippi vagrancy statute was

void on its face for vagueness; that the conduct for which

she was prosecuted was conduct protected by the First

Amendment, the Privileges and Immunities, Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment and the Fifteenth Amendment; that her prosecution

was utterly groundless in fact and was a device designed

to harass and punish her and thus to intimidate prospec

tive Negro voter registration applicants, denying them, on

racial grounds, the franchise in federal, state and local elec

tions. The district court denied the petition without hearing

3

On this record, did the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit err in sustaining the ruling of the district court

that petitioner was required to exhaust her Mississippi

remedies ?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. The case involves 28 U. S. C. §§2241, 2251 (1958),

in pertinent part as follows:

§ 2241. Power to grant writ.

(a) Writs of habeas corpus may be granted by the

Supreme Court, any justice thereof, the district courts

and any circuit judge within their respective jurisdic

tions.

(c) The writ of habeas corpus shall not extend to

a prisoner unless—

# # # * #

(3) He is in custody in violation of the Constitu

tion or laws . . . of the United States; . . .

§ 2251. Stay of State court proceedings.

A justice or judge of the United States before whom

a habeas corpus proceeding is pending, may, before

final judgment or after final judgment of discharge, or

pending appeal, stay any proceeding against the per

son detained in any State court or by or under the

authority of any State for any matter involved in the

habeas corpus proceeding.

on the ground of failure to exhaust Mississippi state judi

cial remedies.

4

After the granting of such a stay, any such proceed

ing in any State court or by or under the authority of

any State shall be void. If no stay is granted, any

such proceeding shall be as valid as if no habeas corpus

proceedings or appeal were pending.

2. The case involves Miss. Code Aw .. 1942, § 2666(c)

(Recomp. Vol. 1956):

§ 2666. Vagrants, who are.

The following persons are and shall be punished as

vagrants, viz.:

-at. jx,w •7T w w

(c) All persons able to work, having no property

to support them, and who have no visible or known

means of a fair, honest and reputable livelihood. The

term “visible and known means of a fair, honest and

reputable livelihood,” as used in this section, shall be

construed to mean reasonably continuous employment

at some lawful occupation for reasonable compensation,

or a fixed and regular income from property or other

investment, which income is sufficient for the support

and maintenance of such person.

3. The case also involves the First, Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States.

5

Statement

This petition brings for review a judgment below deny

ing federal habeas corpus. Petitioner seeks release from

the custody of respondents, the County Attorney and

Sheriff-Jailer of Lowndes County, Mississippi, who hold

petitioner pursuant to Mississippi state vagrancy charges

under Miss. Code A nn . § 2666(c) (Recomp. Vol. 1956),

set forth at p. 4 supra. The district court having denied

the petition without return or hearing, the following alle

gations must be taken as true for purposes of review.1

The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) is an

association of civil rights and local citizenship groups

working in Mississippi to achieve, by peaceful and lawful

means, the equal civil rights of Negroes and all persons and,

particularly, to educate, assist and encourage Negroes to

register and vote in local, state and national elections free

of racial discrimination (Petition, Appendix II infra, 16a).

Now and during many years past, the county registrar of

Lowndes County, Mississippi, has denied and is denying

Negroes the right to register to vote by reason of race, in

violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and

42 U. S. C. A. § 1971 (1964); 42 U. S. C. §§ 1983, 1985 (1958).

In 1961, the voting age population of Lowndes County was

16,460 white and 8362 Negro; there were 5869 registered

white voters and 63 registered Negro voters; these figures

have not substantially changed (21a).2 One of COFO’s pur-

1 The petition is set out in its entirety in Appendix III hereto,

pp. 15a-26a infra.

2 The Government has brought suit against the registrar of

Lowndes County and others to enjoin these discriminatory prac

tices. United States v. Mississippi, 229 F, Supp. 925 (S. D. Miss.

1964), rev’d, 380 U. S. 128 (1965).

6

Petitioner is a 21-year-old white girl, a New York domi

ciliary and a college graduate, employed full-time by COFO

as a voter registration worker (16a). Her duties for COFO

include: interviewing Negro citizens of Mississippi for the

purpose of educating, encouraging and assisting them to

register to vote; accompanying such Negroes to the place of

voting registration for the purpose of supporting their ef

forts to register free of racial discrimination; observing

conduct by state officials or other persons calculated to

racially disfranchise Negroes in violation of the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments; and participating in the ad

ministrative activities of COFO’s voter registration pro

gram (16a-17a). In return for her services, COFO supplies

her decent lodgings (in the home of a well-known, respected

retired Negro minister in Columbus, Mississippi), meals,

support, maintenance, and reasonable livelihood, including

all things necessary to sustain her as a reputable member

of the community (17a). In addition, petitioner receives

from her mother in New York sufficient money to meet all

her needs (18a).

December 28, 1964, in the course of her COFO employ

ment, petitioner, with two COFO co-workers, was present

in the county courthouse for Lowndes County, assisting

Negro voter registration applicants by: (1) directing them

to the voter registration office; (2) supporting them, by

her presence as an observer, against intimidation and

harassment; and (3) interviewing them after their attempts

to register, for the purpose of ascertaining whether the

registrar was obstructing their attempts to register (18a).

While conducting themselves in these activities in a peace

poses is to educate, assist and encourage Negro citizens and

residents of Lowndes County to register to vote (16a).

7

ful and orderly manner, the three workers were arrested

by a deputy sheriff who had been informed that they were

COFO workers (18a-19a). Charged with vagrancy, peti

tioner offered to show the arresting officer money and a

“vagrancy form” prepared by COFO against such a con

tingency, which stated that petitioner was a COFO em

ployee. The officer refused to look at the form and held

them for vagrancy (19a-20a). The following day an au

thorized COFO agent went to the County Attorney and

informed him: that petitioner was a New York domiciliary,

a college graduate, a COFO employee; that by arrange

ment of COFO she lived without expense to herself in

the home of a well-known and respected retired Negro

minister in the same town where she was arrested and

held; that COFO supplied petitioner all her meals and

necessaries. The COFO agent also showed the County

Attorney a telegram dated that morning from petitioner’s

mother in New York, stating that the mother had assumed

and would continue to assume full responsibility for pro

viding her daughter all her decent needs as a respectable

member of the community in Mississippi or elsewhere. Re

spondent County Attorney nevertheless persisted in holding

and prosecuting petitioner on the entirely unfounded charge

of vagrancy (20a-21a).

Consequently, on January 5, 1965, in advance of her state

trial, petitioner filed by counsel a petition for writ of

habeas corpus, challenging the Mississippi vagrancy stat

ute on its face and as applied to her, as violative of her

federal rights of free speech, association and assembly, her

federal privilege to assist Negroes to register to vote in

federal elections, and her federal guarantee against harass

ment designed and effective to deter Negro voting regis

tration. She alleged that the prosecution was in further

ance of an official state-wide policy of discrimination against

8

Negroes and disfranchisement of Negroes by reason of

race (22a-24a). She further asserted that she had been ar

rested without probable cause and that she was being de

tained in a jail segregated by force of Mississippi statute

(23a). The United States District Court for the Northern

District of Mississippi denied the petition on its face on the

ground that petitioner had not exhausted her Mississippi

state remedies as required by Application of Wyckoff, 196 F.

Supp. 515 (S. D. Miss. 1961), 6 R ace Relations L. Rpte.

786, petition for immediate hearing and for leave to pro

ceed on original papers denied, id. at 793 (5th Cir. 1961),

petition for habeas corpus denied, id. at 794 (Circuit Jus

tice Black, with whom Mr. Justice Clark concurs, 1961);

and Brown v. Bayfield, 320 F. 2d 96 (5th Cir. 1963), cert,

denied, 375 U. S. 902 (1963) (la). In so holding, the court

rejected petitioner’s contention—the principal issue in this

case—that exhaustion of state remedies is not required

in petitioner’s circumstances.

January 5, 1965, the order denying the petition was

entered; District Judge Clayton granted petitioner’s appli

cation for a certificate of probable cause under 28 U. S. C.

§2253 (1958), and petitioner’s notice of appeal was filed.

January 22,1965 the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

granted petitioner’s motion for leave to docket the appeal

and proceed on verified copies of the papers comprising the

record below, and set the case specially for expedited hear

ing on typwritten briefs. Such briefs were filed and the case

was argued February 2,1965.3 August 16,1965, the order of

the District Court was affirmed by a panel of the Circuit

3 For the information of the Court, District Judge Clayton made

informal arrangements with the appellees for petitioner Hillegas’

release from physical confinement, and for the stay of her state

trial, pending the appellate proceedings in this ease. Nothing

of this appears in the record.

9

Court. The majority opinion, by Judge Jones joined by

District Judge Sheehy, held that the decisions in Wyckoff

and Brown v. Bayfield, supra, controlled this case (Opinion,

Appendix II infra, 2a). Judge Brown, concurring under

the compulsion of Brown v. Bayfield, pointed out that

Wyckoff was inapposite both to Brown v. Bayfield and to

the present case (6a-7a), noted that Brown v. Bayfield,

“the victim of inadequate presentation” (4a), incorrectly

followed Wyckoff, and, upon careful examination of statu

tory and judicial history first presented to a federal ap

pellate court in petitioner’s brief in the present ease (6a)

and upon analysis of decisions of this Court subsequent

to Brown v. B ay field (9a-lla), concluded that the latter

decision was wrong and should be overruled (4a, 11a).

Petitioner thereupon applied for rehearing en banc. Sep

tember 27, 1965, pursuant to Fifth Circuit practice, the

application was denied by the panel which had heard the

appeal.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I.

The Case Presents an Important Issue Respecting the

Federal Judicial Power and Obligation to Protect Civil

Rights, Not Heretofore Decided by This Court.

This case raises a question of cardinal importance in

volving the relation of state and federal courts under the

Supremacy Clause of the Constitution and the national

habeas corpus jurisdiction created by Congress in 1867 and

now codified in 28 U. S. C. § 2241(c) (3) (1958). That ques

tion is whether a federal district court empowered to dis

charge state prisoners “in custody in violation of the Con

stitution or laws . . . of the United States,” ibid., can and

1 0

should decline to entertain, pending state court trials and

appeals, a factually detailed application for habeas corpus

by a prisoner who alleges that she is confined under mesne

process of a state criminal court in a prosecution which is

groundless because aimed at punishing conduct protected

by the First and Fourteenth Amendments, a prosecution

whose design and effect are to harass and intimidate the

prisoner and others similarly situated so as to repress their

exercise of federal freedoms of expression to encourage

Negro voter registration in a state which has unconstitu

tionally disfranchised the Negro.

A more important question can hardly be imagined. Upon

its correct disposition depends in large measure the power

and obligation of the federal district courts throughout the

country to protect individuals from state prosecutions which

are used as instruments to repress them and deprive them

of their federally guaranteed freedoms. Surely, as this

Court has recently recognized, “The assumption that de

fense of a criminal prosecution will generally assure ample

vindication of constitutional rights is unfounded in such

cases,” Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479, 486 (1965);

prosecution is itself a potent weapon for the destruction of

constitutional liberties, cf. Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F. 2d 226,

231-232 (5th Cir. 1965); thus, reversal of a state criminal

conviction by the Supreme Court of the United States or a

post-conviction federal habeas corpus court comes after the

damage has been done. See Cox v. Louisiana, 348 F. 2d

750 (5th Cir. 1965). Amsterdam, Criminal Prosecutions

Affecting Federally Guaranteed Civil Rights: Federal

Removal and Habeas Corpus Jurisdiction to Abort State

Court Trial, 113 U. Pa. L. Eev. 793, 794-805, 828-842 (1965).

Due implementation of the Supremacy Clause requires

1 1

federal judicial intervention to terminate such state prose

cutions in their inception.

It is petitioner-appellant’s contention that the Congress

of the United States recognized this truth following the

Civil War, and, between 1866 and 1875, gave the federal

courts of first instance ample jurisdiction to do the job.

The three essential jurisdictional grants were the habeas

corpus statute of 1867 involved in the present case; the

civil rights removal statute of 1866, extended in 1875, now

28 U. S. C. § 1443 (1958), see Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F. 2d

336 (5th Cir. 1965) cert, granted October 11, 1965; and the

grant of civil rights equitable jurisdiction in 1871, now

28 U. S. C. § 1343 (1958).

Post-Reconstruction judicial decisions treated the three

jurisdictional grants with scant hospitality. Heedless of the

congressional design to employ federal judicial power for

the effective vindication of civil rights, this Court in Doug

las v. City of Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943), disallowed

federal injunction of state prosecutions which infringed

First Amendment freedoms. The Court had already given

a narrow reading to the civil rights removal statute in a

line of decisions from Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. 8. 313

(1880), to Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906); and,

in the same spirit, had shackled the imperative process

of the federal writ of habeas corpus by the doctrine of

exhaustion of state remedies, invented out of whole cloth in

Ex parte Roy all, 117 U. S. 241 (1886). But these constrain

ing judicial inventions could withstand neither the scrutiny

of historical study directed to the purposes of the Recon

struction legislation nor the demands of a federalism char

acterized by national commitment to the protection of indi

vidual liberties. In Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964),

1 2

and Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965), the Court

substantially repudiated the bases of Douglas v. City of

Jeannette; in Georgia v. Rachel, No. 147, it has granted

certiorari to reexamine the scope of the civil rights re

moval jurisdiction; and in Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 416

(1963), it explicitly recognized the inconsistency of the

exhaustion doctrine, in at least some of its latter-day exten

sions, with the congressional intendment of the habeas

corpus jurisdiction.

The present proceeding was brought to test the applica

tion of the exhaustion doctrine to civil rights cases in light

of the historical insight of Fay v. Noia. No better case

for the purpose could be found. Under the allegations of

the petition, which the courts below accepted as true, peti

tioner is being prosecuted in a Mississippi state court for

conduct plainly protected by the First Amendment, the

design and effect of the prosecution being to harass and

intimidate her and others similarly situated so as to coerce

them to forego exercise of vital federal freedoms. Never

theless, the District Court and the Court of Appeals (one

judge disagreeing) denied relief on the sole ground of

failure to exhaust state remedies. An informal arrangement

by the District Judge stayed the state prosecution pending

appellate proceedings and thus guaranteed the appeal

against mootness4—a constant danger to federal appellate

review in this sort of pretrial habeas corpus proceeding.

(Needless to say, such arrangements will not likely be

made in the future should the Court decline to review the

present case.) Petitioner has presented to the Court of

Appeals, and will present to this Court, historical materials

not previously available and which are indispensable to a

See note 3 supra.

1 3

just appreciation of the congressionally intended scope and

function of federal habeas corpus. Moreover, the time is

now especially propitious for disposition of the exhaustion

question by this Court. The Court now has before it on

certiorari questions concerning the scope of the civil rights

removal jurisdiction; the removal legislation of 1866 and

the habeas corpus legislation of 1867 have a common history

and are intimately related parts of a federal judicial re

medial scheme. Full canvass of the issues concerning an

ticipatory federal jurisdiction in state criminal prosecutions

affecting civil rights, and an appropriate disposition of

those issues in view of the full range of alternative forms

of federal process, can be assured only if certiorari is

granted here and this case heard in conjunction with the

civil rights removal cases.

This Court has not discussed the application of the

doctrine of exhaustion of state remedies to a case in which

petition for federal habeas corpus was made prior to state

trial for almost sixty years, see United States ex rel. Drury

v. Lewis, 200 U. S. 1 (1906), and has never discussed the

application of the doctrine to a harassment prosecution

threatening First Amendment freedoms and the equal civil

rights of Negroes—prime concern of the Reconstruction

Congress which enacted the habeas corpus legislation. The

questions are pressing ones today; the implication of Fay

v. Noia for those questions is unclear; these considerations,

petitioner submits, make the present case an appropriate

one for the exercise of the Court’s certiorari jurisdiction.

1 4

II.

The Decision Below Is Wrong and Seriously Impairs

Federal Judicial Power to Protect National Civil Rights.

A.

Federal Habeas Corpus Courts Are Empowered to

Discharge From Mesne Restraints Petitioners Held to

Answer Unconstitutional State Prosecutions.

The national habeas corpus statute, 28 U. S. C. § 2241

(c)(3) (1958), authorizes federal courts to discharge on

habeas corpus state prisoners “in custody in violation of

the Constitution or laws . . . of the United States.” It is

well settled that the section empowers release before trial

of persons detained on state criminal charges which the

State cannot constitutionally apply to their conduct. Wild-

enhus’s Case, 120 U. S. 1 (1887); In re Loney, 134 U. S. 372

(1890); In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1 (1890); Hunter v. Wood,

209 U. S. 205 (1908); Ex parte Boy all, 117 U. S. 241, 245-

250 (1886) (dictum); Cook v. Hart, 146 U. S. 183, 194-195

(1892) (dictum); Whitten v. Tomlinson, 160 U. S. 231, 241-

242 (1895) (dictum); Baker v. Grice, 169 U. S. 284, 290

(1898) (dictum); United States ex rel. Drury v. Lewis, 200

U. S. 1, 6-8 (1906) (dictum).

B.

Petitioner’s Prosecution Is Unconstitutional.

The state statute under which this petitioner is charged

cannot constitutionally be applied to petitioner’s conduct

for several reasons:

(1) If Miss. Code A n n . § 2666(c) (Recomp. Vol. 1956),

set out at p. 4 supra, makes it criminal to work in a

1 5

courthouse for COFO as a voter registration worker, receiv

ing from COFO adequate lodging and food and from peti

tioner’s parents all additional money required to meet peti

tioner’s needs (with assurance of further funds both from

COFO and from petitioner’s mother should they be needed),

then the statute abridges petitioner’s freedom of speech (see

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 (1945); Staub v. Baxley,

355 U. S. 313 (1958); N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415

(1963); Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex

rel. Virginia State Bar, 377 U. S. 1 (1964), holding that or

ganizational activity like petitioner’s is protected speech),

freedom to associate with COFO (see, e.g., N. A. A. C. P.

v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958); Bates v. Little RocJc, 361

U. S. 516 (1960); Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 (1960);

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigating Committee, 372

U. S. 539 (1963), striking down lesser impediments than

absolute prohibition with respect to associations like

COFO), and freedom to assemble in the courthouse with

Negro voting registration applicants and other COFO

workers for the purpose of giving the applicants support

(this is a fortiori from Edivards v. South Carolina, 372

U. S. 229 (1963); Fields v. South Carolina, 375 TJ. S. 44

(1963); Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 IT. S. 776 (1964); Cox v.

Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965) ). It also abridges peti

tioner’s Fourteenth Amendment privilege to assist, en

courage and educate Negro citizens to register to vote in

federal elections (see Hague v. C. I. 0. 307 U. S. 496 (1939)

(opinion of Mr. Justice Eoberts)) and the Fourteenth

Amendment privilege of those Negroes to register to vote

in federal elections (cf. United States v. Classic, 313 U. S.

299 (1941)), as well as their Fifteenth Amendment free

dom to register to vote in all elections free of racial dis

crimination (cf. United States v. Raines, 362 U. S. 17

(I960)). If the statute does not apply to the state of facts

1 6

described in the first paragraph, then there is no factual

basis whatever for the charge against petitioner, and her

punishment under the statute deprives her of due process

of law for that reason. Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S.

199 (1960); Garner v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 157 (1961);

Fields v. Fairfield, 375 U. S. 248 (1963); Barr v. Columbia,

378 U. S. 146 (1964).

(2) Application of the statute to petitioner is also pre

cluded because the design and effect of this prosecution is

to enforce a policy of racial discrimination by public of

ficials of the State of Mississippi in violation of the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments and 42 U. S. C. A. § 1971

(1964); 42 U. S. C. §§ 1983, 1985 (1958). See Dombrow-

ski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965). It is immaterial

that the policy is not expressed in Miss. Code Auk. § 2666

(c) (Recomp. Vol. 1956) itself. See Peterson v. Greenville,

373 U. S. 244 (1963); Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267

(1963); Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153 (1964). The

policy pervades Mississippi’s statute books as well as its

public life. See, e.g., Miss. Const., art. 8, §§ 201, 205, 207;

art. 10, §225; art. 12, §§ 241-A, 244; Miss. Code An n .

§§ 2056(7), 2339, 4065.3 (Recomp. Vols. 1956); Miss. Laws,

1st Extra. Sess. 1962, chs. 4, 9, 16, 20.

(3) Finally, Miss. Code An n . § 2666(c) (Recomp. Vol.

1956) is on its face void for vagueness in that it makes

criminality of a salaried person turn on whether the salary

amounts to “reasonable compensation.” See cases cited in

Note, 109 U. Pa. L. R ev. 67, 92-93 (1960), particularly

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81 (1921),

and Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U. S. 445 (1927). Such

indefiniteness in a criminal statute is unallowable under

1 7

the Fourteenth Amendment, at least where greater defi

niteness is practicable (as it obviously is here: compare

the provision of § 2666(c) applicable to persons having an

income from property or investment, which requires that

the income be “sufficient for . . . support and maintenance”).

The limited inroad into Cohen made by United States v.

National Dairy Prods. Co., 372 U. S. 29 (1963), expressly

distinguishing Cohen, 372 U. S. at 36, does not save the

statute, since it operates in the First Amendment area,

see, e.g., N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 IJ. S. 415 (1963);

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963); Bouie v. Columbia,

378 U. S. 347 (1964).

C.

A Federal Habeas Corpus Applicant in Petitioner’s

Situation Is Not Required to Exhaust State Judicial

Remedies.

Since petitioner is thus in custody in violation of the Con

stitution, the only obstacle to her release on habeas corpus

in advance of state trial is the doctrine of exhaustion of

state remedies. Petitioner has not, and contends she need

not, exhaust Mississippi state remedies on the facts of this

case; the District Court and the Fifth Circuit held that

Application of Wyckoff and Brown v. Ray field5 6 obliged her

to do so. Plainly, the evolution of the exhaustion doctrine

5 Application of Wyckoff, 196 F. Supp. 515 (S. D. Miss. 1961),

6 Race Relations L. Rptr. 786, petition for immediate hearing

and for leave to proceed on original papers denied, id. at 793 (5th

Cir. 1961), petition for habeas corpus denied, id. at 794 (Circuit

Justice Black, with whom Mr. Justice Clark concurs); Brown v.

Rayfield, 320 F. 2d 96 (5th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 375 U. S. 902

(1963).

18

by the Fifth Circuit, from Wychoff to Brown v. Bayfield

to the present case,6 carries the doctrine far beyond any

of this Court’s decisions, and abuts at a result which en

tirely perverts the habeas corpus legislation enacted by

Congress.

(1) Wychoff, Brown v. Bayfield and 28 U. S. C. § 2254.

In Wychoff the petitioner, a freedom rider, was convicted

by an Ex Officio Justice of the Peace of Hinds County, Mis

sissippi, of breach of the peace (congregating with others

with intent to provoke a breach of the peace and refusing

to move on at the lawful order of a peace officer), arising

out of her attempt, with other freedom riders, to integrate

the bus terminal waiting room in Jackson. She was sen

tenced to $200 fine and two months imprisonment, the im

prisonment sentence suspended. Under Mississippi law,

her conviction could be appealed for trial de novo before a

jury in the County Court, and from conviction by the

County Court an appeal lay to the Circuit Court, thence

to the Supreme Court of Mississippi. Mississippi statutes

allowed the appeals without cost or bond on proper filing of

a pauper’s oath. Petitioner, who was represented by re

tained counsel at the justice’s trial, did not appeal. Within

the period for appeal she filed a federal habeas corpus peti

tion, asserting that the conduct for which she had been

convicted was protected, inter alia, by the First and Four

teenth Amendments, that the prosecution was brought to

enforce racial segregation in violation of the Equal Protec- 6

6 The present ease involves an extension of the exhaustion re

quirement beyond that imposed in Wychoff and Brown v. Bayfield,

for the reasons set out at pp. 53-57 infra.

1 9

tion Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and that she had

been denied a federally guaranteed right of jury trial in

the justice court. She further alleged that she was unable to

bear the cost of taking state appeals. The respondent’s

return denied that the purpose of the prosecution was to

enforce racial segregation, alleged that the trial and con

viction were fair and regular, and asserted that state rem

edies were not exhausted as required by 28 U. S. C. § 2254

(1958). After hearing, the district court denied the petition

on the ground of failure to exhaust state remedies, holding

that the record in the justice court showed that petitioner

had waived jury trial, pointing out that petitioner still had

an available appeal for trial de novo in the County Court,

and noting that Mississippi provided a pauper’s procedure

for taking the appeal and that petitioner was represented by

able counsel. Because the respondent’s return had denied

that the prosecution was designed to enforce unconstitu

tional segregation and petitioner had offered no evidence in

support of her allegations to this effect, the district court

took petitioner’s claims in this respect as unproved. Peti

tioner noted an appeal and asked the Fifth Circuit for

leave to proceed on the original papers and for an imme

diate hearing. The court denied both motions, agreeing

with the district court that petitioner had failed to exhaust

state remedies under 28 U. 8. C. § 2254.

In Brown v. Bayfield, the two habeas petitioners were

arrested while walking in tandem, in an orderly fashion,

with four other individuals, on a street in Jackson, Missis

sippi, carrying an American flag and a placard protesting

racial discrimination. Charged with violation of a Jackson

ordinance prohibiting parading without a license, they were

entitled to trial in a justice court and thereafter to appeals

2 0

as in Wyckoff. Apparently prior to their justice trial,7

they petitioned for federal habeas corpus, asserting that

the conduct for which they were charged could not con

sistently with the First and Fourteenth Amendments be

punished by the State. Petitioners undertook to state a case

of “circumstances rendering [state remedies] . . . ineffec

tive to protect [their] . . . rights” within 28 U. S. C. § 2254

by allegations (a) that all Mississippi public officials were

committed to a policy of racial discrimination, as demon

strated by Mississippi’s massive resistance legislation; (b)

that judges of the various state courts (all elected officials)

gave tacit if not open support to the discriminatory policy

in their election campaigns, and that the policy was reflected

in their judicial decisions and opinions; and (c) that, by

reason of the congestion of civil rights cases in the Missis

sippi courts, and delays compelled by Mississippi trial and

appellate procedures, the June 1961 freedom rider cases

had not yet been disposed of by the Mississippi Supreme

Court in the summer of 1963, and a like or greater delay

was in prospect for the petitioners. The return denied that

the Mississippi courts would not fairly protect petitioners’

federal rights, and asserted that § 2254 precluded enter

taining the petitions. The district court denied relief on

this ground; pending appeal the petitioners posted bond

and were released from ja il; the Fifth Circuit, relying on the

Wychoff decision, dismissed the appeals for insubstantiality

on the merits.

7 The Fifth Circuit opinion in Brown v. Bayfield does not make

clear whether the federal habeas corpus application in that case

was filed prior to or after the justice tria l; language in the opinion

suggests the latter. However, Judge Brown’s concurring opinion

in the present case, based upon examination of the Brown v.

Bayfield record, indicates that Brown was a pretrial habeas case.

2 1

Any evaluation of Brown v. Bayfield must begin with the

observation that the court there quite erroneously supposed

the case was governed by 28 U. S. C. § 2254. That statute

has no application whatever to federal habeas corpus pe

titions filed in advance of a state court trial. The section

applies only to “a person in custody pursuant to the judg

ment of a State court,” and the legislative history makes

clear what in any event would be apparent (e.g., by com

parison of this language with that of 28 U. S. C. § 2253

(1958)): that the phrase “judgment of a State court” was

chosen to cover post-conviction habeas cases and to exclude

cases in which federal habeas corpus was sought prior to

state trial. The original section in the House bill which

became the 1948 Judicial Code required exhaustion of avail

able state remedies by a habeas petitioner who was “in

custody pursuant to the judgment of a State court or au

thority of a State officer.” See H. E. 3214, 80th Cong.,

§ 2254. The Senate Committee on the Judiciary rewrote the

section to make several changes, among them omission of

the phrase “or authority of a State officer.” The committee

report explains the purpose of the change to “ . . . eliminate

from the prohibition of the section applications on behalf

of prisoners in custody under authority of a State officer

but whose custody has not been directed by the judgment

of a State court. If the section were applied to applica

tions by persons detained solely under authority of a State

officer it would unduly hamper Federal courts in the pro

tection of Federal officers prosecuted for acts committed

in the course of official duty.” Sen. Eep. No. 1559, 80th

Cong., 2d Sess. 9 (1948). Moreover, the origins of this 1948

statute, disclosing the concerns to which it responded,

make patent that § 2254 has not even analogical significance

in pretrial habeas cases. See Amsterdam, Criminal Prose

2 2

cutions Affecting Federally Guaranteed Civil Rights: Fed

eral Removal and Habeas Corpus Jurisdiction to Abort

State Court Trial, 113 U. Pa. L. Rev. 793, 890 n. 415, 902-

903 (1965). Accepting arguendo the decision in Wyckoff

that § 2254 applies to a prisoner confined under a justice

court conviction notwithstanding state law gives him a

right of trial de novo in a court of record, the statute

plainly had no application to the pre-justice-trial petition

filed in Brown v. Rayfield and the present case.

Of course, § 2254 is merely a partial codification of the

doctrine of exhaustion of state remedies, which was judi

cially developed in and following Ex parte Roy all, 117 U. S.

241 (1886), and which, as a flexible judicial doctrine of

comity, does apply to pretrial federal habeas petitions. See

in addition to Royall, e.g., Cook v. Hart, 146 U. S. 183

(1892); New Tori v. Eno, 155 U. S. 89 (1894); Whitten v.

Tomlinson, 160 U. S. 231 (1895); Moss v. Glenn, 189 U. S.

506 (1903); United States ex rel. Drury v. Lewis, 200 U. S.

1 (1906). The origin and scope of that judicially developed

doctrine in relation to the function of federal habeas corpus

in civil rights cases is considered in the ensuing sections

of this petition; for present purposes it is sufficient to

note that the doctrine is a judicial creature, unfettered

by statute against judicial evolution, and which “prescribes

only what should ‘ordinarily’ be the proper procedure; all

the cited cases from Ex parte Royall to [Ex parte] Hawk

[321 U. S. 114 (1944)] recognize that much cannot be fore

seen, and that ‘special circumstances’ justify departure

from rules designed to regulate the usual case. The excep

tions are few but they exist. Other situations may de

velop. . . . ” Darr v. Bur ford, 339 U. S. 200, 210 (1950)

(dictum). See, e.g., the authorities cited at p. 14, supra.

23

To determine the appropriate application of the judicial

doctrine to such cases as the present one and Brown v.

Bayfield, it will be necessary to canvass the statutory his

tory of federal habeas corpus jurisdiction and the evolu

tion of the court-made exhaustion requirement in relation

to it. From such a survey the conclusion clearly emerges

that federal habeas corpus is immediately available to one

in petitioner’s circumstances.

(2) Legislative history.

Habits of thought generated by three quarters of a cen

tury of application of the exhaustion doctrine tend to make

American courts and lawyers today think of federal habeas

corpus almost exclusively as a post-conviction remedy. But

the nineteenth century Congresses which expanded the

habeas corpus jurisdiction to its present scope8 thought in

no such terms. Prior to the twentieth century, post-convic

tion use of the writ was rare though not unknown;9 the

English courts had more frequently used the writ in its

various forms “for removing prisoners from one court

8 The present federal habeas corpus jurisdiction described in

28 U. S. C. § 2241 (1958), is the product of statutes of 1789,

1833, 1842 and 1867. Act of September 24, 1789, ch. 20, § 14,

1 Stat. 73, 81-82; Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, 4 Stat. 632; Act

of August 29, 1842, ch. 257, 5 Stat. 539-540; Act of February 5,

1867, ch. 28, 14 Stat. 385. Each succeeding statute added to the

previously given grant of habeas power. The four grants were

consolidated without substantial change in Rev. Stat. §§ 751-753,

which remained in force without significant modification until the

1948 revision of Title 28, U. S. C. That revision produced present

§ 2241, whose “changes in phraseology” were not designed to affect

substantive change. See Revisor’s Note to 28 U. S. C. § 2241 (1958).

9 Examination of the texts clearly indicates that in England

the writ was most commonly used, and thought of, as pretrial,

not post-conviction, process. E.g., 3 Comyns. Digest of the Laws

of England 454-455 (1785); 2 Hale, Pleas of the Crown 143-

2 4

into another, for the more easy administration of justice” ;* 4 * * * * * 10 11

common-law habeas corpus ad subjiciendum developed

principally as a remedy against executive detention with

out, or prior to, judicial trial ;1] and the great Habeas Corpus

Act of 1679, 31 Charles II, ch. 2, as Blackstone noted, ex

tended by its terms “only to the case of commitments for

such criminal charge, as can produce no inconvenience to

public justice by a temporary enlargement of the prisoner;

all other cases of unjust imprisonment being left to the

148, 210-211 (1st American ed., Philadelphia, 1847); IV Bacon’s

Abridgment 563-605, Habeas Corpus (Philadelphia 1844). One

of the relatively infrequent instances of its post-conviction use

is the celebrated Bushell’s case, Vaughan, 135, 6 How. St. Tr. 999,

124 Eng. Rep. 1006 (1670), discharging petitioners from a con

tempt commitment. Several of the precedents cited in Bushell’s

case involve similar summary commitment. In this country, the

Supreme Court of the United States early employed the federal

writ in behalf of persons committed for trial, to release them

on bail, United States v. Hamilton, 3 Dali. 17 (U. S. 1795), or

to discharge them for want of probable cause, Ex parte Bollman,

4 Cranch 75 (1807) ; but in Ex parte Watkins, 3 Pet. 193 (1830),

the Court held that where the respondent’s return to the writ

showed that the petitioner was held by virtue of the judgment

of a court having jurisdiction, the inquiry on habeas corpus ended

and no reexamination would be made of the lawfulness of the

judgment. Watkins thus restricted post-conviction use of habeas

corpus to a very narrow compass; it was only with Ex parte Lange,

18 Wall. 163 (1873), that expansion began via the “jurisdictional”

fiction, and only with Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458 (1938)

that federal habeas emerged from the fiction in its modern role

as a post-conviction remedy. See note 14 infra. The state courts,

too, generally disallowed postconviction use of the writ prior to

the twentieth century. See cases collected in Thompson, Abuses

of the Writ of Habeas Corpus, 18 A m . L. Rev. 1, 17-18 n. 1 (1884).

See also Oaks, Habeas Corpus in the States, 32 U. Ch i L R ev 243

258-264 (1965).

10 3 Blackstone Commentaries 129 (6th ed., Dublin 1775).

Blackstone here refers to forms of the writ other than habeas

corpus ad subjiciendum.

11 See 9 Holdswoeth, A History of English Law 111-119

(1926).

25

habeas corpus at common law.” 12 Consistently with this

background, the several congressional statutes extending

federal habeas corpus to state prisoners13 were clearly de

signed, in the classes of cases with which each was princi

pally concerned, to give prisoners held by state authorities

in advance of state court proceedings an immediate federal

judicial proceeding to secure their release.14 The history of

the first two of these enactments, in 1833 and 1842, was

carefully examined in In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1, 70-75

(1890), and the conclusion drawn that their whole purpose

was to allow federal judicial intervention into the state

criminal process before state court trial. Indeed, no other

conclusion is possible. The Force Act of March 2, 1833,

ch. 57, 4 Stat. 632, was Congress’ response to John C. Cal

houn and his threat to take South Carolina out of the Union

12 3 Blackstone, supra note 10, at 137. For the history of the act

see 9 Holdswokth, supra note 11, at 115-119; Chafee, How Hu

man Eights Got Into the Constitution 51-64 (1952).

18 The habeas corpus jurisdiction given by the First Judiciary Act

by its express terms did not extend to state prisoners except where

they were “necessary to be brought into court to testify.” Act of

September 24, 1789, ch. 20, § 14, 1 Stat. 73, 81-82.

14 The conclusion in note 9 supra that development of federal

habeas corpus as a post-conviction remedy may be dated at the

earliest from 1873 and is largely a twentieth century phenomenon

is supported by all commentators. See, e.g., Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S.

391 (1963) ; Note, The Freedom Writ—The Expanding Use of

Federal Habeas Corpus, 61 Habv. L. Eev. 657 (1948); Hart,

Foreword, The Supreme Court, 1958 Term, 73 Habv. L. Eev. 84,

101-121 (1959); Reitz, Federal Habeas Corpus: Postconviction

Remedy for State Prisoners, 108 U. Pa. L. Eev. 461 (1960) ; Reitz,

Federal Habeas Corpus: Impact of an Abortive Stale Proceeding,

74 Harv. L. Eev. 1315 (1961) ; Brennan, Federal Habeas Corpus

and State Prisoners: An Exercise in Federalism, 7 Utah L. Eev.

423 (1961) ; Bator, Finality in Criminal Law and Federal Habeas

Corpus for State Prisoners, 76 Harv. L. Eev. 441 (1963) ; Note,

Federal Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners: The Isolation Prin

ciple, 39 N. Y. U. L. Rev. 78 (1964).

2 6

in resistance to the Tariff. See 1 Morison & Commager,

Growth of the A merican R epublic 475-485 (4th ed. 1950);

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 401 n. 9 (1963). The Nullifica

tion Ordinance was an open denial of federal supremacy,

and it was “apparent that the constitution of the courts in

South Carolina makes it necessary to give the revenue offi

cers the right to sue in the federal courts.” Cong. Debates,

vol. 9, pt. 1, 260 (Mr. Wilkins, who reported the bill and

was its floor manager in the Senate, id. at 150 (1/21/33),

246 (1/28/33, 1/29/33)); see also Mr. Frelinghuysen’s re

marks, id. at 329-332 (2/2/33). Hence Congress responded

by extending the civil jurisdiction of the federal courts to

all cases arising under the revenue laws (§ 2), by authoriz

ing removal of civil and criminal cases against federal

revenue officers (§ 3), and by giving the federal courts and

judges habeas corpus power to discharge from state custody

all persons “in jail or confinement, where he or they shall

be committed or confined on, or by any authority or law,

for any act done, or omitted to be done, in pursuance of a

law of the United States, or any order, process, or decree,

of any judge or court thereof. . . . ” (§ 7, 4 Stat. 634). The

clear purpose of these provisions as a lot was wdiolly to

supersede state court jurisdiction in cases affecting the

tariff and to give the federal courts power immediately and

effectively to enforce the tariff against concerted state re

sistance, including state judicial resistance. Similarly, the

Act of August 29, 1842, ch. 257, 5 Stat. 539-540, was de

signed to cope with the problem of the famous McLeod

case, in which the New York courts nearly touched off a

major international incident by refusing to relinquish juris

diction over a British subject held for murder, who claimed

that the acts with which he was charged were done under

27

authority of the British government. People v. McLeod,

25 Wend. 482 (Sup. Ct. N. Y. 1841). McLeod was acquitted

at his trial, but the need for an expeditious federal remedy

to abort the state court process in such eases was strongly

felt, and the 1842 statute was its product. See the speech

of Mr. Berrien, who introduced the Senate bill, Cong.,

Globe, 27th Cong., 2d Sess. 444 (4/26/42), quoted in Neagle,

135 II. S. at 71-72.

Thus the thirty-ninth Congress, which in 1867 further

extended the federal habeas corpus jurisdiction to “all cases

where any person may be restrained of his or her liberty

in violation of the constitution, or of any treaty or law of

the United States,” acted against a background of legisla

tive practice which had previously employed the federal

writ to discharge individuals held for state trial, in advance

of that trial, in cases where their detention for subjection

to the state criminal process was itself destructive of fed

eral interests that the state judicial proceedings could not

be expected to vindicate. The Act of February 5, 1867, ch.

28, 14 Stat. 385, predecessor of the present 28 U. S. C.

§ 2241(c) (3) (1958), was Reconstruction legislation. Its

first section granted new habeas corpus power in the lan

guage quoted above, made elaborate provision for sum

mary hearing and summary disposition by the federal

judges, and provided that :

“ . . . pending such proceedings or appeal, and until

final judgment be rendered therein, and after final

judgment of discharge in the same, any proceeding

against such person so alleged to be restrained of his

or her liberty in any State court, or by or under the

authority of any State, for any matter or thing so

heard and determined, under and by virtue of such

2 8

writ of habeas corpus, shall be deemed null and void/’

§ 1, 14 Stat. 386.15 16

Its second section gave another and different remedy to

state criminal defendants having federal constitutional de

fenses : review of the highest state court judgment by the

Supreme Court of the United States on writ of error. 14

Stat. 386-387. In view of the juxtaposition of these reme

dies, the provisions expressly recognizing that federal

habeas corpus courts would anticipate and forestall state

judicial processes, and the pre-1867 usage with the writ,

one need hardly plumb the legislative debates to conclude,

as this Court recently has concluded, that: “Congress

seems to have had no thought . . . that a state prisoner

should abide state court determination of his constitutional

defense—the neeessary predicate of direct review by [the

Supreme Court] . . .—before resorting to federal habeas

corpus. Rather, a remedy almost in the nature of removal

from the state to the federal courts of state prisoners’ con

stitutional contentions seems to have been envisaged.” Fay

v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 416 (1963). The legislative materials,

moreover, are eloquent on the point.

The genesis of the statute was a resolution offered by

Representative Shellabarger shortly after the convening

of the Congress in December, 1865 and immediately agreed

to by the House, Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 87

(12/19/65): “Resolved, That the Committee on the Judi

ciary be directed to inquire and report to this House, as

soon as practicable, by bill or otherwise, what legislation

is necessary to enable the courts of the United States to en

15 The successor of this provision is present 28 U. S. C. § 2251

(1958), under which petitioner herein has moved for a stay of

state proceedings.

2 9

force the freedom of the wives and soldiers of the United

States under the joint resolution of Congress of March 3,

1865, and also to enforce the liberty of all persons under

the operation of the constitutional amendment abolishing

slavery.” There is no pertinent “joint resolution” of “March

3, 1865,” and the evidence is persuasive that the “March 3”

action intended by the reference is the Act of March 3,

1863, ch. 81, 12 Stat. 755, a statute protecting Union offi

cers and other persons from civil or criminal liability

for acts or omissions during the rebellion under Presiden

tial order or law of Congress, and authorizing removal

from the state to federal courts of civil or criminal actions

against such persons.16 That this was Shellabarger’s refer

ence appears from the House Judiciary Committee’s sub

sequent reporting of a bill17 which became the Act of May

11, 1866, eh. 80, 14 Stat. 46, substantially amending the

16 Bator, Finality in Criminal Law and Federal Habeas Corpus

for State Prisoners, 76 Harv. L. Rev. 441, 476 n. 80 (1963), reaches

this conclusion. March 3, 1865 was the date of House concurrence

in a Senate concurrent resolution requesting the President to

transmit the proposed Thirteenth Amendment to the state execu

tives, Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 2d Sess. 1416 (3/3/65), but Shella-

barger could not have meant to refer to this resolution, which had

no substantive import. March 3, 1865 was also the date of enact

ment of the Preedmen’s Bureau Act, ch. 90, 13 Stat. 507, but

matters involving implementation of that act would doubtless have

been referred to the House Select Committee on Freedmen, estab

lished by resolution, Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 14

(12/6/65), and which reported, for example, the Amendatory

Freedmen’s Bureau Act of July 16, 1866, ch. 200, 14 Stat. 173.

See Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess, 2743 (5/22/66).

17 The bill was apparently numbered II. K. 238 of the 39th Con

gress, although some pages of the Globe refer to it as H. E. 298.

It was the product of a House Judiciary Committee amendment in

the nature of a substitute to a bill introduced by Representative

Welker. Introduced at Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 196

(1/11/66) ; reported, id. at 1368 (3/13/66); taken up, id. at 1387

(3/14/66).

3 0

removal procedures of the 1863 act to prevent their obstruc

tion by the state courts,18 an act which in turn was amended

by the Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 27, 14 Stat. 385, au

thorizing the issuance of writs of habeas corpus cum causa

by the federal courts to bring before them the bodies of

defendants whose cases had been removed from the state

courts under the 1863 removal provisions.19 On March 15,

1866, in debate on the bill which became the May 11 act,

Shellabarger returned to what appears the theme first

sounded in his resolution of the preceding December:

“Mr. Shellabaegek. I wish to inquire of some mem

ber of the Judiciary Committee whether they intend

by this bill, or any other which they may have in

18 See id. at 1387-1388 (Cook, who reported the bill, id. at 1368

(3/13/66), and was its floor manager, id. at 1387 (3/14/66), in

the House, 3/14/66) ; 2054 (Clark, who reported the bill, id. at

1753 (4/4/66), and was its floor manager, id. at 1880 (4/11/66)

in the Senate, 4/20/66).

19 The act was reported by the Judiciary Committee in each

house. Id. at 4096 (7/24/66) (House), 4116 (7/24/66) (Senate).

Its purpose was to take from state custody defendants whose cases

had been removed into the federal courts, id. at 4096 (7/24/66)

(Wilson, who reported the bill and was its floor manager, Hid.,

in the House); Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 2d Sess. 729 (1/25/67)

(Trumbull, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, who reported

the bill, Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 2d Sess. 729 (1/25/67) in the

Senate), and thereby to permit the federal court to determine the

validity of the defendant’s detention under the arrest, ibid.

(Johnson, in the Senate). Together with the Act of May 11, see

supra, text at note 18, and the habeas corpus statute, this enact

ment evidences congressional concern to provide speedy and effi

cient federal judicial remedies for state court defendants. Con

temporaneously with these three bills, the bill which was to

become the First Civil Rights Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, 14 Stat.

27, -was being processed through Congress. Section 3 of the act as

enacted created the civil rights removal jurisdiction now found in

28 U. S. C. § 1443(2) (1958), and adopted the procedures of the

1863 removal sections with “all acts amendatory thereof.” 14 Stat.

27.

31

preparation, to provide for such eases as one which I

am about to describe, a case which came to my bn owl -

edge about the time of the convening of this Congress,

and which I now state in order to attract to it the at