The Good News Club v. Milford Central School Brief of Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 12, 2001

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The Good News Club v. Milford Central School Brief of Amici Curiae, 2001. e64896ad-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7d785b8b-8ceb-4f41-87b6-1d14c8a7d36b/the-good-news-club-v-milford-central-school-brief-of-amici-curiae. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

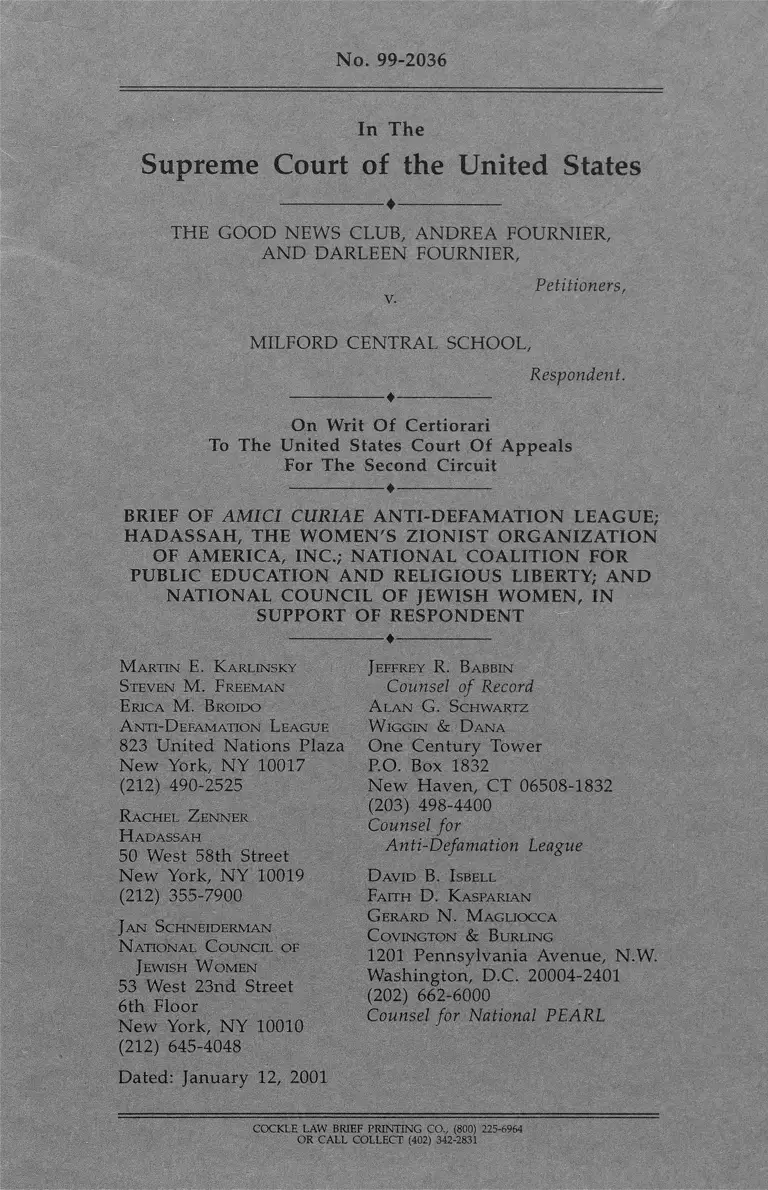

No. 99-2036

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

---------------- ♦ - — — ------- -

THE GOOD NEWS CLUB, ANDREA FOURNIER,

AND DARLEEN FOURNIER,

Petitioners,

v.

MILFORD CENTRAL SCHOOL,

Respondent.

----- -— - — - ♦ -------------—

On Writ O f Certiorari

To The United States Court O f Appeals

For The Second Circuit

-----------------♦ -----------------

BRIEF OF A M ICI CURIAE ANTI-DEFAM ATION LEAGUE;

HADASSAH, THE W O M EN 'S Z IO N IST ORGANIZATION

OF AM ERICA, INC.; NATIONAL COALITION FOR

PUBLIC EDUCATION AND RELIG IO U S LIBERTY; AND

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF JEW ISH WOMEN, IN

SUPPORT OF RESPO N D EN T

— ♦ -----------------

J effrey R. B abbin

Counsel o f Record

A lan G. S chwartz

W iggin & D ana

One Century Tower

P.O. Box 1832

New Haven, CT 06508-1832

(203) 498-4400

Counsel fo r

Anti-Defamation League

D avid B . Isbell

Faith D. K asparian

G erard N. M agliocca

C ovington & B urling

1201 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004-2401

(202) 662-6000

Counsel fo r National PEARL

M artin E. K arlinsky

S teven M . F reeman

E rica M . B roido

A nti-D efamation L eague

823 United Nations Plaza

New York, NY 10017

(212) 490-2525

R achel Z enner

H adassah

50 West 58th Street

New York, NY 10019

(212) 355-7900

J an S chneiderman

N ational C ouncil of

J ewish W omen

53 West 23nd Street

6th Floor

New York, NY 10010

(212) 645-4048

Dated: January 12, 2001

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................................... ii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE....................................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT........................................... 2

ARGUMENT........................................................................ 4

I. RESPONDENT DID NOT VIOLATE PETI

TIONERS' FREE SPEECH RIGHTS....................... 4

A. Respondent's Policy Is Reasonable................ 5

B. Respondent's Policy Is Viewpoint Neutral. . 9

II. THE ESTA BLISH M EN T CLAUSE BARS

RESPONDENT FROM ALLOWING PETI

TIO N ERS' PROPOSED USE OF PUBLIC

SCHOOL FACILITIES.................................. 17

A. A Reasonable Elementary School Student

Would Not Understand the Distinction

Between Government Speech and Private

Speech ..................... 19

B. The Good News Club's Meetings Would

Have the Appearance of a School-Spon

sored, After-School Program........................... 24

C. The Good News Club Would Be One of Only

a Few Private Groups Meeting on Public

School Premises..................................... 27

D. To Allow the Good News Club to Meet at

the Milford Central School Would Consti

tute an Unprecedented Erosion of Establish

ment Clause Values........................................... 29

CONCLUSION.................................................................... 30

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

11

C a se s

Ambach v. Norwick, 441 U.S. 68 (1979)............... 2, 11, 30

Bell v. Little Axe Indep. Sch. Dist. No. 70, 766 F.2d

1391 (10th Cir. 1985).................................................. 21, 22

Board of Educ. of the Westside Community Schs.

(Dist. 66) v. Mergens, 496 U.S. 226 (1990)..........passim

Bronx Household of Faith v. Community Sch. Dist.

No. 10, 127 F.3d 207 (2d Cir. 1997)^..................... 10, 11

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954)................. 2

Brown v. Woodland Joint Unified Sch. Dist., 27 F.3d

1373 (9th Cir. 1994).......................................................... 22

Campbell v. St. Tammany's Sch. Bd., 206 F.3d 482

(5th Cir. 2000), reh'g denied, 231 F.3d 937 (5th

Cir. 2 0 0 0 )...................................... ............................. 11

Capitol Square Review & Advisory Bd. v. Pinette, 515

U.S. 753 (1995)............................... 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 28

Cornelius v. NAACP Legal Defense & Educ. Fund,

Inc., 473 U.S. 788 (1985)............................. 5, 6, 7, 9, 14

County of Allegheny v. ACLU Greater Pittsburgh

Chapter, 492 U.S. 573 (1989)............................. 12, 18, 19

Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578 (1987)

................................................................ 6, 11, 19, 20, 22, 25

Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962)................................. 10

Good News/Good Sports Club v. School Dist. of Ladue,

28 F.3d 1501 (8th Cir. 1994)...................................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

22

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Educ., 333 U.S.

203 (1948)....................................................6, 8, 11, 25, 27

Lamb's Chapel v. Center Moriches Union Free Sch.

Dist., 508 U.S. 384 (1993).......................................passim

Lamb's Chapel v. Center Moriches Union Free Sch.

Dist., 959 F.2d 381 (2d Cir. 1992). . ........................20, 26

Lee v. Weisman, 505 U.S. 577 (1992) .. 10, 11, 19, 25, 26, 29

Lubbock Civil Liberties Union v. Lubbock Indep. Sch.

Dist., 669 F.2d 1038 (5th Cir. 1982)................. ........... 26

Lynch v. Donnelly, 465 U.S. 668 (1984) ......................12, 18

Marsh v. Chambers, 463 U.S. 783 (1983)......................... 19

Peck v. Upshur County Bd. of Educ., 155 F.3d 274

(4th Cir. 1998)................................................................... 22

Perry Education Ass'n v. Perry Local Educators'

Ass'n, 460 U.S. 37 (1983)................................................. .6

Quappe v. Endry, 772 F. Supp. 1004 (S.D. Ohio

1991), aff'd, 979 F.2d 851 (6th Cir. 1992)................... 28

Rosenberger v. Rector & Visitors of Univ. of Va., 515

U.S. 819 (1995)........................................................... passim

Santa Fe Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Doe, 120 S. Ct. 2266

(2000).................................................................... 18, 26, 29

School Dist. of Abington Township v. Schempp, 374

U.S. 203 (1963).................................................... 11, 20, 25

School Dist. of Grand Rapids v. Ball, 473 U.S. 373

(1985), overruled in part on other grounds by

Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203 (1997)............... passim

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Stone v. Graham, 449 U.S. 39 (1980)................................ 12

Tilton v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 672 (1971)....................... 20

Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38 (1985)................. 10, 19, 25

Widmar v. Vincent, 454 U.S. 263 (1981)

12, 15, 18, 20, 23, 28

S ta tu tes

20 U.S.C. § 1011k(c)............................................................ 12

20 U.S.C. § 1062(c)(1).......................................................... 12

20 U.S.C. § 1066c(c)............................................................ 12

20 U.S.C. § 1068e..................................................................12

20 U.S.C. § 1103e..................................................................12

20 U.S.C. §§ 4071-4074........................................................ 22

20 U.S.C. § 8897................................................................. 12

25 U.S.C. § 1803(b)............................................................. 12

25 U.S.C. § 1813(e)............................................................. 12

25 U.S.C. § 2503(b)(2)......................................................... 12

25 U.S.C. § 3306(a)............................................................. 12

29 U.S.C. § 2938(a)(3)..........................................................12

42 U.S.C. § 604a(j)............................................................... 13

42 U.S.C. § 2753(b)(1)(C)....................................................13

42 U.S.C. § 3027(a)(14)(A)(iv).......................................... 13

42 U.S.C. § 5001(a)(2)......................... 13

V

42 U.S.C. § 9807(a)(9).......................................................... .13

42 U.S.C. § 9858k(a).............................................................. 13

42 U.S.C. § 9920(c)..................................... 13

42 U.S.C. § 13791(b)(B)(iv)................................................... 13

L eg isla tiv e H ist o r y

130 Cong. Rec. S19231 (daily ed. June 27, 1984)........ 23

130 Cong. Rec. H20934 (daily ed. July 25, 1984)........ 23

S. Rep. No. 98-357 (1984), reprinted in 1984

U.S.C.C.A.N. 2348 ........................................................... 23

M isc e l l a n e o u s

Patricia A. Adler & Peter Adler, Peer Power: Pre

adolescent Culture and Identity (1998).......................... 21

Allisonville Christian Church Website (visited Jan

uary 8, 2001) <http://home.att.net/~allisoncc/

children.htm>....................................... ..........................10

First Union Methodist Church Website (visited

January 8, 2001) <http://www.gbgm-umc.org/

Schenectady/Children%20and%20 Worship.

htm> .............................................. 10

Fowler V. Harper, Fleming James, Jr. & Oscar S.

Gray, The Law of Torts (2d ed. 1986).......................... 22

Wayne R. LaFave & Austin W. Scott, Jr., Criminal

Law (2d ed. 1986)....................................................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

22

http://www.gbgm-umc.org/Schenectady/Children%20and%20_Worship.htm

http://www.gbgm-umc.org/Schenectady/Children%20and%20_Worship.htm

http://www.gbgm-umc.org/Schenectady/Children%20and%20_Worship.htm

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

National Center for Education Statistics, Schools

Serving Family Needs: Extended-Day Programs in

Public and Private Schools (U.S. Dep't of Educ.

Feb. 1997)..................................................................... 26, 27

Jean Piaget & Barbel Inhelder, The Psychology of the

Child (1969)................................................................. 20

Jean Piaget, The Stages of the Intellectual Develop

ment of the Child, in Readings in Child Develop

ment and Personality 291 (Paul Henery Mussen

et al. eds., 4th ed. 1997)................................................ 20

Restatement (Second) of Torts § 464 (1965)..................... 22

Patricia S. Seppanen et al., National Study of Before

and After School Programs (U.S. Dep't of Educ.

1993).................................................................................... 26

Williston on Contracts (4th ed. 1993).................... 22

1

INTEREST OF AM ICI CURIAE1

The Anti-Defamation League ("ADL") was organized

in 1913 to advance good will and mutual understanding

among Americans of all creeds and races and to combat

racial and religious prejudice in the United States. ADL

has always adhered to the principle that these goals and

the general stability of our democracy are best served

through the separation of church and state and the right

to free exercise of religion. To that end, ADL has filed

amicus curiae briefs in many cases before this Court. ADL

is able to bring to the issues raised in this case the

perspective of a national organization dedicated to safe

guarding all persons' religious freedoms.

Hadassah, the Women's Zionist Organization of

America, Inc. ("Hadassah"), is the largest women's and

the largest Jewish membership organization in the United

States with over 300,000 members nationwide. Founded

in 1912, Hadassah is known for funding and maintaining

health care institutions in Israel and has a proud history

of protecting the rights of the Jewish community in the

United States. Hadassah has long been committed to the

principle of strict separation between church and state

that has served as a guarantee for religious freedom and

diversity. In an effort to uphold this fundamental princi

ple, Hadassah has participated as amicus curiae in many

cases before this Court.

The National Coalition for Public Education and Reli

gious Liberty ("National PEARL") is a diverse coalition of

grassroots and national religious, educational and civic

organizations that seeks to preserve religious freedom

and the separation of church and state in public educa

tion. National PEARL has participated in an amicus capac

ity in many cases before this Court.

1 No counsel for any party authored this brief in whole or

in part. No person or entity, other than amici curiae, their

members or their counsel made a monetary contribution to the

preparation and submission of this brief.

2

The National Council of Jewish Women, Inc.

("NCJW") is a volunteer organization, inspired by Jewish

values, that works to improve the quality of life for

women, children and families and strives to ensure indi

vidual rights and freedoms for all. Founded in 1893, the

NCJW has long adhered to the view that religious liberty

and separation of church and state are constitutional

principles that must be protected and preserved in our

democratic society. The NCJW has 90,000 members in

over 500 communities nationwide.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. This Court has long recognized "[t]he importance

of public schools in the preparation of individuals for

participation as citizens, and in the preservation of the

values on which our society rests." Ambach v. Norwick, 441

U.S. 68, 76 (1979); see Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483,

493 (1954). Petitioners question whether a public elemen

tary school may open itself as a forum to certain specified

types of speech and still exclude from that limited forum

religious worship, instruction and indoctrination targeted

at the school's children.2 Amici support respondent's cate

gorical exclusion of that speech as both a reasonable,

viewpoint-neutral limitation, consistent with the Free

Speech Clause of the First Amendment, and as a limita

tion mandated by the Establishment Clause of the First

Amendment.

2. a. Respondent's policy is a reasonable limitation

on use of a public school. Just as the government may

2 Although respondent's policy provides broadly that

school premises may not be used by any organization for

"religious purposes," school officials have interpreted the

policy to exclude only religious worship, instruction and

indoctrination. See J.A. at N4 ("I would interpret [the policy to

exclude] conducting religious services, providing religious

instruction or to an extreme, religious indoctrination into a

philosophy or a belief.").

3

exclude potentially divisive political speech from the

workplace to avoid controversy and the appearance of

political favoritism, a public school may choose to open

itself only to those categories of speech that will further

the interests of the community and the school and to

exclude those categories of speech - whether religious,

political, commercial or other - that may divide the com

munity. While the public school is designed to promote

cohesion among a heterogeneous democratic people, the

Good News Club is designed to do quite the opposite: to

label people as "saved" or "unsaved" and, thus, to pro

mote religious belief in general and Christian belief in

particular.

b. In addition to being reasonable, respondent's

policy is viewpoint neutral because it excludes an entire

category of speech - namely, religion as it is expressed

through religious worship, instruction and indoctrination

- from a limited public forum. The Good News Club's

speech in its evangelizing meetings is distinct from the

kinds of speech permitted under the school's policy. The

Club's meetings are overt religious exercises, equivalent

in all but name and locale to conventional children's

services at churches and synagogues across the country.

The distinction between religion as supplying an editorial

viewpoint and religious worship, instruction and indoc

trination as a subject matter is well recognized in both

case law and federal statutory law. While excluding this

subject matter may in some instances also exclude a point

of view, this Court's precedents are clear that the First

Amendment is violated only if speech is excluded from

the limited public forum solely to suppress the point of

view.

3. The Establishment Clause stands as an indepen

dent bar to the Good News Club's proposed after-school

program for elementary school students because it pro

hibits the public school from appearing to take a position

on questions of religious belief. Here, in light of (1) the

young age and cognitive limitations of the Good News

Club's target audience; (2) the Club's proposed use of a

4

classroom setting immediately after school, very likely

side by side with school-sponsored programs that extend

the day for so many of the nation's elementary school

students; and (3) the nature of the elementary school

forum and the relatively small number of other private

groups meeting there, it would have appeared to a rea

sonable observer that the public school was "sponsoring"

or "endorsing" the Good News Club's meetings.

4. To affirm the Court of Appeals' judgment, this

Court need only agree with - and address - one of these

two propositions, either that the Free Speech Clause per

mits respondent's limitation on outside use of the school

or that the Establishment Clause mandates the limitation.

On the other hand, to reject both, and thereby reverse the

Court of Appeals' judgment, would undermine the ability

of a public school to determine for itself what subjects are

appropriate for inclusion in the educational forum and

would weaken the well-recognized distinction, central to

the concept of public education, between secular learning

on the one hand and religious worship, instruction and

indoctrination on the other. Petitioners' constitutional

views, if adopted by the Court, would thus constitute an

unprecedented erosion of Establishment Clause values

that - because of the age of the students involved here

and the role of public schools in imparting democratic

values to young students - would reverberate well

beyond this particular case. A new generation of children

would grow to maturity associating public schools with

religious worship and religious learning. This should not

be a price that public schools, or the children they edu

cate, must pay for simply accommodating secular groups

like the Girl Scouts and the 4-H Club.

A R G U M E N T

I. R E S P O N D E N T D ID N O T V IO L A T E P E T IT IO N E R S '

FR E E SP E E C H R IG H T S

It is well established that "[t]he necessities of confin

ing a forum to the limited and legitimate purposes for

5

which it was created may justify the State in reserving it

for certain groups or for the discussion of certain topics."

Rosenberger v. Rector & Visitors ofUniv. ofVa., 515 U.S. 819,

829 (1995). Where the State has reserved a forum for

discussion of only certain topics - as even petitioners

acknowledge is the case here, see Pet. Br. 15-17; see also

Pet. App. C12 (District Court opinion) - a restriction on

speech is permissible so long as it is "reasonable in light

of the purpose served by the forum" and viewpoint neu

tral. Rosenberger, 515 U.S. at 829 (internal quotation marks

omitted); accord Lamb's Chapel v. Center Moriches Union

Free Sch. Dist., 508 U.S. 384, 392-93 (1993); Cornelius v.

NAACP Legal Defense & Educ. Fund, Inc., 473 U.S. 788, 806

(1985).

A . R e s p o n d e n t's P o licy Is R e a s o n a b le

Respondent's exclusion of religious worship, instruc

tion and indoctrination,3 both in general and as applied

to the Good News Club specifically, is plainly reasonable.

In Cornelius, this Court held that a federal policy exclud

ing legal defense and political advocacy organizations

from participating in a charity drive aimed at federal

employees was reasonable in light of the forum's purpose

and the surrounding circumstances. See 473 U.S. at

808-10. Observing that a government's decision to restrict

access to a limited public forum need only be reasonable -

not "the most reasonable or the only reasonable limita

tion," id. at 808 - the Court ruled that "avoiding the

appearance of political favoritism" and "avoiding contro

versy" were reasonable bases to exclude such organiza

tions from participation in the drive, id. at 809. As the

Court concluded, "The First Amendment does not forbid

a viewpoint-neutral exclusion of speakers who would

disrupt a [limited public] forum and hinder its effective

ness for its intended purpose." Id. at 811.

3 See supra note 2.

6

Excluding religious worship, instruction and indoc

trination from public school premises similarly avoids

unwarranted controversy and the appearance of favori

tism. Just as the government may exclude categories of

speech so as to " 'insure[ ] peace' in the federal work

place," id. at 810, a public school is surely entitled to open

itself only to those categories of speech that will further

the interests of the school and the community in cohe

siveness and to exclude those categories of speech -

whether religious, political, commercial or other - that

may divide that community. See Perry Education Ass'n v.

Perry Local Educators' Ass'n, 460 U.S. 37, 52 (1983)

("[Exclusion of the rival union may reasonably be con

sidered a means of insuring labor-peace within the

schools."); see also Cornelius, 473 U.S. at 810 ("[T]he Gov

ernment need not wait until havoc is wreaked to restrict

access to a [limited public] forum." (emphasis added)).

That this case involves a forum created by, and iden

tified with, a public school makes the policy of excluding

religious worship, instruction and indoctrination all the

more reasonable. First, state and local school boards are

"afforded considerable discretion" in the operation of

public schools. Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578, 583

(1987). Second, religion is a particularly divisive matter in

the public school context. In the oft-quoted words of

Justice Frankfurter, "[t]he public school is at once the

symbol of our democracy and the most pervasive means

for promoting our common destiny. In no activity of the

State is it more vital to keep out divisive forces than in its

schools . " Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Educ., 333

U.S. 203, 231 (1948) (opinion of Frankfurter, J.) (emphasis

added); see id. at 216-17 ("[T]he public school must keep

scrupulously free from entanglement in the strife of

sects."). "[J]ust as religion throughout history has pro

vided spiritual comfort, guidance, and inspiration to

many, it can also serve powerfully to divide societies and

to exclude those whose beliefs are not in accord with

particular religions or sects . . . . " School Dist. of Grand

7

Rapids v. Ball, 473 U.S. 373, 382 (1985), overruled in part on

other grounds by Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203 (1997).4

Respondent had good reason to believe that the Good

News Club's activities in particular would be contrary to

the mission of a public elementary school, and therefore

would "disrupt [the] forum and hinder its effectiveness."

Cornelius, 473 U.S. at 811. The core purpose of the Good

News Club is to persuade impressionable elementary

school children - that is, "children of tender years, whose

experience is limited and whose beliefs consequently are

the function of environment as much as of free and

voluntary choice," Ball, 473 U.S. at 390 - to follow "the

Word of God" and to accept Jesus Christ as their "per

sonal Savior." E.g., Lodging at BB4 ("How to Lead a Child

to Christ").5 To this end, the Good News Club teaches

that some children are "saved" (those who accept Jesus

Christ as their Savior) and others "unsaved" (those who

do not); and that some children - the "saved" - are going

to go to Heaven while the rest are not. See, e.g., J.A. at

P25, P64-65; Lodging at S12, S17, BB5, BB8, BB10.

Thus, for example, the Good News Club's teacher

"challenges" the "saved" children to "[s]top and ask God

4 There is a particular risk of appearance of favoritism if

only members of a locally dominant faith have the numbers and

resources to maintain an after-school religion club. If there were

only one or two Jewish, Hindu, or Buddhist children in a school,

they could not realistically join clubs analogous to the Good

News Club. These children would feel isolated from their

classmates - and feel less welcome on school property - solely

because of their religions.

5 The Good News Club is one of the "prim ary m inistries" of

the Child Evangelism Fellow ship, Inc. That organization 's

statement of interest in its amicus curiae brief here, at App. 1,

makes clear that its "w hole purpose is to evangelize boys and

girls with the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ and to establish

(discipline) them in the local church for Christian living." See

also Lodging at DD1 (advocating "H elping You Evangelize

Children").

8

for the strength and the 'want' . . . to obey Him" and

"invites" the "unsaved" children "to trust the Lord Jesus

to be your Savior from sin" and to "receive Him as your

Savior." Lodging at BB18, BB24; see also J.A. at P64-65,

P67-68, P70-71, P75. Club materials teach young and

impressionable children that while believers in Jesus

Christ "will also be raised [to Heaven], . . . [i]f a person

does not receive the Lord Jesus as Saviour, he will not be

able to go to Heaven." Lodging at S12, S17. And during

meetings, the children pray to "receive Jesus as their

personal Savior"; listen to "missionary stories" that

"spread[ ] the gospel" and encourage acceptance of Jesus

Christ as the Savior; and sing songs with references to

God and Jesus Christ. E.g., J.A. at P16-17, P22-23, P25,

P28, P66-67, P109; Lodging at BB11, BB47.

In short, while the public school is "[d]esigned to

serve as perhaps the most powerful agency for promoting

cohesion among a heterogeneous democratic people,"

McCollum, 333 U.S. at 216 (opinion of Frankfurter, J.), the

Good News Club is designed to do quite the opposite: to

label children as either "saved" or "unsaved" and, thus,

to promote religious belief in general and Christian belief

in particular. Indeed, the Good News Club expressly

teaches that adherence to a particular faith is essential to

one's standing in the community - that those who "have

received the Lord Jesus as [their] Savior from sin

. . . belong to God's special group - His family." Lodging

at S6. Thus, whether or not the Good News Club is

nominally open to anyone, see J.A. at C2, and whether or

not the Club teaches or promotes "any particular Chris

tian sect's doctrine or theology," id. (emphasis added),

respondent's officials were well justified in believing that

the Good News Club's meetings would be inconsistent

with the purpose of the public school forum. Respon

dent's limitation on the use of its school building was

9

reasonable, and so long as that limitation was also view

point neutral, the Constitution requires no more.6

B. Respondent's Policy Is Viewpoint Neutral

In addition to being reasonable, respondent's policy

is viewpoint neutral because it excludes a distinct cate

gory of speech from a limited public forum. An exclusion

of speech on the basis of content is permissible in a limited

public forum. See Lamb's Chapel, 508 U.S. at 392-93. Lamb's

Chapel simply does not hold that any and all bans on

religious activities in a limited public forum violate the

First Amendment. Respondent's limitation on use of its

forum is an exclusion of content - of an entire subject

matter - and not an exclusion solely of particular view

points bearing on a secular subject matter. The exclusion

is not arbitrary, as shown in the discussion of "rea

sonableness," above. It is also not discriminatory, as it

applies to all speech - that is, to all viewpoints (including

differing sectarian viewpoints) - on the excluded subject

matter of religion as it is expressed through religious

worship, instruction and indoctrination.

Petitioners self-servingly characterize their speech as

"instruction of morals from a religious perspective." E.g.,

Pet. Br. 22. Notwithstanding this effort, however, the

record clearly demonstrates that the Good News Club's

speech at its meetings is different in kind from the speech

permitted under the Milford Central School policy -

including, for example, meetings of the Boy Scouts, the

6 Respondent's policy is of course animated by some of the

considerations underlying the Establishment Clause. See infra

P a rt II (a rg u in g th a t re sp o n d e n t w as req u ir ed by the

E stab lishm en t C lause to exclu d e the Good N ew s C lu b 's

activities from school premises). Nevertheless, for purposes of

the reasonableness inquiry, the school need only show that its

policy is reasonable in light of the forum 's purposes, see

Cornelius, 473 U.S. at 809, without regard to Establishm ent

Clause principles.

10

Girl Scouts and the 4-H Club. The Good News Club's

meetings include vocal group prayers, memorization and

recital of Bible verses and Scripture, religious songs and

discussions based on Bible readings. See, e.g., J.A. at

P16-18, P22-23, P25-26. These are "overt religious exer

cise^]." Lee v. Weisman, 505 U.S. 577, 588 (1992); see

Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38, 72 (1985) (O'Connor, }.,

concurring in the judgment) (calling group vocal prayer

and Bible readings "manifestly religious exercisers]");

Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421, 424-25 (1962) (discussing the

"religious activity" of prayer). They are equivalent in all

but name and locale to conventional church or synagogue

services. Cf. Bronx Household of Faith v. Community Sch.

Dist. No. 10, 127 F.3d 207, 215 (2d Cir. 1997) (describing

"church worship services" as "including] hymn singing,

communion, Bible reading, Bible preaching and teaching"

(internal quotation marks omitted)).

To the extent the Good News Club's meetings differ

from conventional religious services - the meetings

involve, for example, prizes, candy and games - this is

simply because the Club tailors its evangelizing meetings

to its young and impressionable audience. Indeed, the

Good News Club's meetings are virtually indistinguish

able from children's services commonly held at churches

and synagogues across the country, which often involve

singing, puzzles, art, stories and prayer.7

Nor does it matter that the Good News Club's meet

ings contain an "instructional" element. First, that ele

ment of petitioners' meetings does nothing to change the

7 See, e.g., First Union Methodist Church Website (visited

January 8, 2001) <h ttp ://w w w .gbgm -u m c.org /sch en ectad y/

Children%20and%20W orship.htm> (describing "Children and

W orship," a "service that is designed for [children] to be age

appropriate scripture (story telling) and w orship"); Allisonville

Christian Church Website (visited January 8, 2001) <h ttp :/ /

hom e.att.net/~allisoncc/children.htm > (describing "Children's

Worship: Godly Play," a service for children including singing,

story telling, art and food).

http://www.gbgm-umc.org/schenectady/Children%20and%20Worship.htm

http://www.gbgm-umc.org/schenectady/Children%20and%20Worship.htm

http://home.att.net/~allisoncc/children.htm

http://home.att.net/~allisoncc/children.htm

11

essential or overall nature of their speech. Second, the

distinction between religious instruction and secular

instruction is not one merely of perspective. To the con

trary, religious and secular instruction serve fundamen

tally different purposes. See, e.g., School Dist. of Abington

Township v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 223-25 (1963) (distin

guishing religious instruction from "nonreligious moral

inspiration" and "teaching of secular subjects");

McCollum, 333 U.S. at 226 (opinion of Frankfurter, J.)

(distinguishing between "secular instruction in subjects

concerning religion" and "sectarian teaching"). Religious

instruction is designed first and foremost to train adher

ents of a particular religion in the tenets of that religion's

faith and practice. It is not designed, as secular education

is, to "prepar[e] . . . individuals for participation as

citizens." Ambach v. Norwich, 441 U.S. 68, 76 (1979).

Petitioners' suggestion that no line can be drawn

between religion as a viewpoint and religious worship,

instruction and indoctrination as a subject matter is with

out merit. First, although the distinction between content

and viewpoint is not always a precise one, see Rosenberger,

515 U.S. at 831, there is no reason to believe that officials

would not usually be able to draw the requisite distinc

tions, see, e.g., Campbell v. St. Tammany's Sch. Bd., 206 F.3d

482, 487 (5th Cir. 2000), reh'g denied, 231 F.3d 937 (5th Cir.

2000) (per curiam); Bronx Household, 127 F.3d at 215. In

fact, in the present case - as in Campbell and Bronx House

hold - public officials were able to determine from the

face of petitioners' application that their proposed use

was for an excluded subject matter.

Moreover, the task of distinguishing between "overt

religious exercise[s]," Lee, 505 U.S. at 588, and other

forms of speech is hardly foreign to the law. Indeed, the

lines that respondent's officials must draw in implement

ing their policy are no different from, or more difficult to

draw than, the lines that courts and public officials are

required to draw under current law - for example,

between teaching the Bible as a religious text and teach

ing it as literature, see, e.g., Edwards, 482 U.S. at 606-08

12

(Powell, ]., concurring); Stone v. Graham, 449 U.S. 39, 42

(1980) (per curiam), or between "religious" Christmas

displays and "secular" Christmas displays, see, e.g.,

County of Allegheny v. ACLU Greater Pittsburgh Chapter,

492 U.S. 573, 611-13 (1989); Lynch v. Donnelly, 465 U.S.

668, 679-86 (1984). See generally Widmar v. Vincent, 454

U.S. 263, 271 n.9 (1981) (noting that "the Establishment

Clause requires the State to distinguish between 'religious'

speech . . . and 'nonreligious' speech" (emphasis added)).

Any number of federal statutes contemplate the same sort

of line-drawing without constitutional infirmity.8

8 See, e.g., 20 U.S.C. § 1011k(c) ("[N ]o project assisted with

funds under subchapter VII of this chapter . . . shall ever be used

for religious worship or a sectarian activity . . . . "); 20 U.S.C.

§ 1062(c)(1) ("N o grant may be made under this chapter for any

educational program, activity, or service related to sectarian

instruction or religious worship, or provided by a school or

department of divinity."); 20 U.S.C. § 1066c(c) ("No loan may be

made under this part for any educational program, activity or

service related to sectarian instruction or religious worship . . . . ");

20 U.S.C. § 1068e ("The funds appropriated under section 1069f

of this title may not be used . . . for . . . any religious worship or

sectarian activity . . . . " ) ; 20 U .S.C. § 1103e ("The funds

appropriated under section 1103g of this title may not be

used . . . for . . . any religious worship or sectarian activity . . . . ");

20 U.S.C. § 8897 ("N othing contained in this chapter shall be

construed to authorize the making of any payment under this

chapter for religious worship or instruction."); 25 U.S.C. § 1803(b)

("Funds provided pursuant to this subchapter shall not be used

in connection with religious worship or sectarian instruction.”); 25

U.S.C. § 1813(e) ("No construction assisted with funds under

this section shall be used for religious zoorship or a sectarian

activity . . . . "); 25 U.S.C. § 2503(b)(2) ("Funds provided under

any grant made under this chapter m ay not be used in

connection with religious zoorship or sectarian instruction."); 25

U.S.C. § 3306(a) ("None of the funds made available under this

subchapter may be used . . . for any religious zoorship or sectarian

activity."); 29 U.S.C. § 2938(a)(3) ("Participants shall not be

employed under this chapter to carry out the construction,

13

Petitioners seek to blur the line between subject mat

ter and viewpoint by trying to place themselves simul

taneously on both sides of it. They propose a seemingly

simple truth: religion is both the subject matter and the

viewpoint of their speech. See Pet. Br. 22-24. But even

accepting this premise, the conclusion does not follow

operation, or maintenance of any part of any facility that is used

or to be used for sectarian instruction or as a place for religious

worship . . . . "); 42 U.S.C. § 604a(j) (''No funds provided directly

to in stitu tio n s or organ ization s to provid e serv ices and

administer programs under subsection (a)(1)(A) of this section

sh a ll be exp en d ed for sectarian worship, instruction, or

proselytization."); 42 U.S.C. § 2753(b)(1)(C) (allow ing federal

grants to be used for student work-study that "does not involve

the construction, operation, or maintenance of so much of any

facility as is used or is to be used for sectarian instruction or as a

place for religious worship"); 42 U .S.C. § 3027(a)(14)(A )(iv)

(requiring a state seeking federal aid for construction of a center

for the elderly to promise that "the facility will not be used and

is not intended to be used for sectarian instruction or as a place

for religious zoorship"); 42 U.S.C. § 5001(a)(2) (providing federal

grants to support volunteer pro jects for the elderly, but

excluding "projects involving the construction, operation, or

maintenance of so much of any facility used or to be used for

sectarian instruction or as a place for religious zoorship"); 42 U.S.C.

§ 9807(a)(9) ("[N ]o participant will be employed on projects

involving . . . the construction, operation, or maintenance of so

much of any facility as is used or to be used for sectarian

instruction or as a place for religious worship."); 42 U .S.C .

§ 9858k(a) ("N o financial assistance provided under this

subchapter . . . shall be expended for any sectarian purpose or

activity, including sectarian worship or instruction.''); 42 U.S.C.

§ 9 9 2 0 (c ) ("N o fund s p ro v id ed d ire c tly to a re lig io u s

o rg an iza tio n to p ro v id e a ss is ta n ce u nd er any p rogram

described in subsection (a) shall be expended for sectarian

zoorship, instruction, or proselytization."); 42 U .S .C .

§ 13791(b)(B)(iv) ("Religious organizations . . . shall not provide

any sectarian instruction or sectarian zoorship in connection with

an activity funded under this subchapter . . . . " ) (emphases

added to all).

14

that respondent's exclusion of their meetings violates the

Constitution. This Court has made clear that the Free

Speech Clause is violated only if the government

excludes speech from a limited public forum "solely

because [it deals] with [an otherwise includible] subject

from a religious standpoint." Lamb's Chapel, 508 U.S. at

394 (emphasis added); accord Cornelius, 473 U.S. at 806

("[T]he government violates the First Amendment when

it denies access to a speaker solely to suppress the point of

view he espouses . " (emphasis added)). Thus, where

- as here - there is evidence that the government has

excluded speech at least in part for a reason "other

than . . . that the presentation would have been from a

religious perspective," Lamb's Chapel, 508 U.S. at 393-94,

the mere fact that a religious perspective is also excluded

does not give rise to a constitutional violation.9

Were the test otherwise, the government's authority

to limit the use of a limited public forum to certain

subject matters would become meaningless, because pri

vate speakers could always evade the limitations by com

bining speech on an excluded subject matter with a

modicum of speech on an otherwise included subject

matter. On petitioners' view of the law, for example, a

religious group could require a public school to open

itself to religious worship merely by including in the

religious service a sermon on a secular subject like child

rearing. This cannot be the law, for the government

would then have lost its ability to "confin[e] a forum to

the limited and legitimate purposes for which it was

created." Rosenberger, 515 U.S. at 829.

9 By referring to the Good News Club's speech as having an

"ad d itio n al lay er," the C ourt of A ppeals recognized that

religion can be both a subject m atter and a viewpoint - and that

the Constitution is violated only when religion is excluded solely

on the basis of viewpoint. Pet. App. A15; see also id. at A16 ("We

conclude . . . that the Good News Club is doing something other

than simply teaching moral values." (emphasis added)).

15

Petitioners incorrectly rely on Rosenberger to argue

that the First Amendment does not distinguish between a

religious subject matter and a religious perspective. See

Pet. Br. 20-21.10 The speech in Rosenberger was a news

paper - what the Court called "a pure forum for the

expression of ideas," 515 U.S. at 844 - and its exclusion

by the public university from a Student Activities Fund

("SAF") was based on "editorial viewpoint ]," Id. at 831;

see also id. at 844 ("[T]he student publication is not a

religious institution, at least in the usual sense of that

term as used in our case law . . . . "). Here, by contrast,

the Good News Club did not seek meeting space for a

journalistic venture, but rather meeting space in which to

engage in an evangelizing religious activity involving

religious worship, instruction and indoctrination.

Respondent's limitation on its forum excluded speech

that was inherently part of the religious activity, and not

an editorial viewpoint in an exchange of ideas.

Nothing in Rosenberger precludes the drawing of an

intelligible distinction between religion as a viewpoint

and religious worship, instruction and indoctrination as a

subject matter, and then constitutionally excluding the

latter from a limited public forum. To the contrary, the

Rosenberger Court merely held that the university had not

drawn this distinction in excluding the student news

paper from the SAF:

10 Reliance on Widmar for this point is even more plainly

misplaced. See, e.g., Amicus Curiae Brief of Douglas Laycock

15-16. Widmar held that a state university's prohibition on use of

its buildings "for purposes of religious worship or religious

teaching" was an impermissible content-based restriction. 454

U.S. at 267-75. The forum in Widmar, however, was an open

public forum. Accordingly, the Court did not consider a subject-

based exclusion of religious worship and teaching in a more

limited public forum, and the Court did not conduct a limited

public forum analysis.

16

[T]he University does not exclude religion as a

subject matter but selects for disfavored treat

ment those student journalistic efforts with reli

gious editorial viewpoints. Religion may be a

vast area of inquiry, but it also provides, as it did

here, a specific premise, a perspective, a stand

point from which a variety of subjects may be

discussed and considered. The prohibited per

spective, not the general subject matter, resulted in

the refusal [to fund the student newspaper], for

the subjects discussed were otherwise within the

approved category of publications.

Id. at 831 (emphasis added); see id. at 832 ("[T]he Univer

sity justifies its denial of SAF participation to [the student

newspaper] on the ground that the contents . . . reveal an

avowed religious perspective.").11 In the present case,

however, Milford Central School did not exclude the

Good News Club's speech because - let alone "solely

because," Lamb's Chapel, 508 U.S. at 394 - religion pro

vided its "specific premise," "perspective," or "stand

point"; instead, the school excluded the Good News

Club's speech because religious worship, instruction and

indoctrination constituted its subject matter.

Finally, petitioners raise the specter of excessive

entanglement between church and state, apparently argu

ing that allowing a school to make the distinction

11 In arguing that Rosenberger rejected any legal distinction

between religion as a subject matter and religion as a viewpoint,

petitioners rely heavily on the fact that the dissent in Rosenberger

characterized the university 's guidelines as excluding "the

entire subject matter of religious apologetics." 515 U.S. at 896

(Souter, d issen tin g ); see Pet. Br. 20-21. H ow ever, the

d isag reem en t b etw een the m a jo rity and th e d isse n t in

R osen berger w as not over w hether the govern m en t m ay

constitutionally exclude speech from a limited public forum on

the ground that religion constitutes its subject matter, but rather

over whether the university had done so. See 515 U.S. at 896

(Souter, J ., d issenting) ("T h e C ourt, of cou rse, reads the

Guidelines differently . . . . ").

17

between religious worship, instruction and indoctrination

and speech from a religious perspective is itself constitu

tionally impermissible. See Pet. Br, 24-26. This argument

is without merit. Indeed, petitioners' supposed concern is

contrary to their own stated position that one cannot

draw a subject matter distinction between their speech

and that of others. That is, petitioners' entanglement

argument presupposes that the school district can legit

imately distinguish between the subject matter of peti

tioners' religious speech and the subject matters of other

groups' secular speech. Moreover, a broad and categorical

exclusion of religious worship, instruction and indoc

trination - even when such speech includes a sermon or

other expression of religious views on an otherwise

includible subject - minimizes the entanglement between

church and state, because then the state need not monitor

each individual service or lesson plan.

In sum, unlike the school in Lamb's Chapel and the

university in Rosenberger, respondent did not exclude

speech on the basis of a religious viewpoint. To the con

trary, private individuals and groups were expressly per

mitted to discuss those subjects otherwise permitted

under the school's policy from a religious perspective.

See, e.g., J.A. at G6, N14-15. Instead, respondent excluded

an entire category of speech from school premises. This

limitation was reasonable and was applied without dis

crimination against any particular viewpoint. Nothing in

the Constitution, or in this Court's jurisprudence, forbids

that policy. II.

I I . T H E E S T A B L IS H M E N T C L A U SE B A R S R E S P O N

D E N T F R O M A L L O W IN G P E T IT IO N E R S ' P R O

P O S E D U S E O F P U B L IC S C H O O L F A C IL IT IE S

Had the Milford Central School embraced the Good

News Club as an after-school program for its elementary

school students, it would have violated the Establishment

Clause. Stated otherwise, the Establishment Clause

stands as an independent bar to petitioners' proposed

activities on school premises, regardless of the presence

18

or absence of valid limitations on the use of the forum

under the Free Speech Clause. Indeed, the Milford Cen

tral School could have justified its exclusion of the Good

News Club's meetings solely by reference to the compel

ling state interest in complying with the Establishment

Clause. See, e.g., Capitol Square Review & Advisory Bd. v.

Pinette, 515 U.S. 753, 761-62 (1995) ("There is no doubt

that compliance with the Establishment Clause is a state

interest sufficiently compelling to justify content-based

restrictions on speech."); accord Lamb's Chapel, 508 U.S. at

394-95; Widmar, 454 U.S. at 271.

Whatever else it may mean, the Establishment

Clause, "at the very least, prohibits government from

appearing to take a position on questions of religious

belief or from 'making adherence to a religion relevant in

any way to a person's standing in the political commu

nity.' " County of Allegheny, 492 U.S. at 594 (quoting Lynch,

465 U.S. at 687 (O'Connor, J., concurring)) (emphasis

added). Allowing impressionable elementary school stu

dents to join with petitioners for religious worship,

instruction and indoctrination in a school classroom,

immediately after school, would violate these prohibi

tions.

In arguing to the contrary, petitioners emphasize

their view that the Good News Club would be meeting on

public school premises pursuant to a formally neutral

access policy. See Pet. Br. 30-39. However, this Court

stated only last Term that "the Establishment Clause for

bids a State to hide behind the application of formally

neutral criteria and remain studiously oblivious to the

effects of its actions." Santa Fe Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Doe, 120

S. Ct. 2266, 2278 n.21 (2000) (internal quotation marks

omitted). In Justice O'Connor's words, "[N]ot all state

policies are permissible under the Religion Clauses sim

ply because they are neutral in form." Capitol Square, 515

U.S. at 777 (O'Connor, J., concurring in part and concur

ring in the judgment).

Thus, the crucial question for Establishment Clause

purposes is whether, notwithstanding Milford Central

19

School's formally neutral access policy, a reasonable

observer would conclude from the Good News Club's

meeting on school premises that the government was

"lending its support to the communication of a religious

organization's religious message." County of Allegheny,

492 U.S. at 601; see also Capitol Square, 515 U.S. at 777

(O'Connor, concurring in part and concurring in the

judgment) ("[Wjhen the reasonable observer would view

a government practice as endorsing religion, . . . it is our

duty to hold the practice invalid."). In light of (1) the

young age and cognitive limitations of the Good News

Club's targeted audience; (2) the fact that the Good News

Club's meetings would take place in a classroom setting

immediately after school, when many students attend

school-sponsored, after-school programs; and (3) the

small number of other outside groups meeting on school

premises at the same time, amici submit that the answer

to this question is plainly yes.

A. A Reasonable Elementary School Student

Would Not U nderstand the D istin ctio n

Between Government Speech and Private

Speech

First and foremost, the age of the students involved

in this case - six to twelve year olds - compels the

conclusion that the Milford Central School was required

to deny the Good News Club's application to conduct

religious worship, instruction and indoctrination on

school premises. Indeed, to hold otherwise would repre

sent a marked departure from existing law.

In analyzing whether government action would be

perceived as an endorsement of religion, this Court has

long placed great emphasis on the age and cognitive

maturity of the likely audience. See, e.g., Lee, 505 U.S. at

593-94; Board of Educ. of the Westside Community Schs.

(Dist. 66) v. Mergens, 496 U.S. 226, 250-51 (1990) (plurality

opinion); Edwards, 482 U.S. at 583-84; Ball, 473 U.S. at 390;

Wallace, 472 U.S. at 81 (O'Connor, concurring in the

judgment); Marsh v. Chambers, 463 U.S. 783, 792 (1983);

20

Widmar, 454 U.S. at 274 n.14; Tilton v. Richardson, 403 U.S.

672, 685-86 (1971); Schempp, 374 U.S. at 252-53 (Brennan,

J., concurring). In Widmar, for example, the Court explic

itly relied on the cognitive maturity of university stu

dents in concluding that they would be able to

distinguish between private speech and government

speech. See 454 U.S. at 274 n.14. And in Mergens, a plu

rality of the Court extended the reasoning of Widmar to

high school students: "We think that secondary school

students are mature enough and are likely to understand

that a school does not endorse or support student speech

that it merely permits on a nondiscriminatory basis . . . .

[Tjhe few years difference in age between high school

and college students [does not] justif[y] departing from

Widmar." 496 U.S. at 250 (plurality opinion) (internal

quotation marks omitted).12

The many years of difference in age between elemen

tary school students and college students, however, do

justify departing from Widmar in this case. See, e.g.,

Edwards, 482 U.S. at 584 n.5 (acknowledging the distinc

tion between university students and younger students

and stating that " '[t]his distinction warrants a difference

in constitutional results' " (quoting Schempp, 374 U.S. at

252-53 (Brennan, J., concurring)). Research in psychology

indicates that six- to twelve-year-old children are sub

stantially less cognitively mature than adolescents, and

less likely to understand abstract concepts like justice or

diversity. See, e.g., Jean Piaget & Barbel Inhelder, The

Psychology of the Child passim (1969); Jean Piaget, The

Stages of the Intellectual Development of the Child, in Read

ings in Child Development and Personality 291 (Paul Henry

12 Lamb's Chapel, like Mergens, involved a high school. See

Lamb's Chapel v. Center M oriches Union Free School Dist., 959 F.2d

381, 383-84 (2d Cir. 1992). Moreover, student age was not an

issue in that case because the film series on child rearing was

directed toward an adult audience. See id. at 384.

21

Mussert et al. eds., 4th ed. 1997).13 Similarly, psychologi

cal research reveals that elementary school students are

highly susceptible to peer pressure. See, e.g., Patricia A.

Adler & Peter Adler, Peer Power: Preadolescent Culture and

Identity passim (1998).

This research supports the common-sense assump

tion that, in the context of programs held immediately

after the "formal" school day on school premises, a rea

sonable elementary school student would not understand

the "crucial difference between government speech

endorsing religion, which the Establishment Clause for

bids, and private speech endorsing religion, which the

Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses protect." Mergens,

496 U.S. at 250 (plurality opinion). Instead, the objective

observer in the position of an elementary school student

at the Milford Central School would mistakenly believe

that the Good News Club's meetings were sponsored or

endorsed by his or her school.14 Similarly, an elementary

13 See also Bell v. Little Axe Indep. Sch. Dist. No. 70, 766 F.2d

1391, 1404 & n . l l (10th Cir. 1985) (discussing expert testimony

that "a child between the ages of 6 and 11 does not have the

cognitive ability to 'appreciate the difference between his point

of view and that of som ebody else. It 's as if he sim ply

assim ilates and takes, unthinkingly, what other people have

taught to him ' ").

14 The fact that there is no evidence in the record that

students were confused during the time the Good News Club

met on school prem ises pursuant to the D istrict C ourt's

preliminary injunction is immaterial. See Pet. Br. 38. As Justice

O'Connor explained in Capitol Square, the endorsem ent test does

not focus "on the actual perception of individual observers, who

naturally have differing degrees of know ledge," but on "the

perspective of a hypothetical observer." 515 U.S. at 779-80

(O 'C onnor, ]., con cu rrin g in part and con cu rrin g in the

judgment).

22

school student faced with his or her peers attending the

Good News Club's meetings would very well feel coerced

by peer pressure to attend and to "receive [Jesus Christ]

as [his or her] Savior." Lodging at BB24. Those students

forbidden to attend by their parents would correspon

dingly feel excluded, different and diminished within

their own school.

These conclusions are further reinforced by the near

uniform judgments of courts - including this Court - and

of Congress. In the Establishment Clause context alone,

courts have routinely taken note of the cognitive limita

tions of young children. See, e.g., Edwards, 482 U.S. at

583-84; Ball, 473 U.S. at 390; Peck v. Upshur County Bd. of

Educ., 155 F.3d 274, 287 n * (4th Cir. 1998); Good News/

Good Sports Club v. School Dist. ofLadue, 28 F.3d 1501, 1509

& n.18 (8th Cir. 1994); Brown v. Woodland Joint Unified Sch.

Dist., 27 F.3d 1373, 1378-79 (9th Cir. 1994); Bell, 766 F.2d at

1404-05 & n .ll. Courts have noted the same cognitive

limitations in other legal contexts as well. See, e.g., 3

Fowler V. Harper, Fleming James, Jr. & Oscar S. Gray, The

Law of Torts § 16.8 & n.18 (2d ed. 1986) (discussing courts'

treatment of children in the tort law context); Wayne R.

LaFave & Austin W. Scott, Jr., Criminal Law § 4.11 (2d ed.

1986) (same in the criminal law context); 5 Williston on

Contracts ch. 9 (4th ed. 1993) (same in the contract law

context).15

Similarly, Congress specifically dropped elementary

schools from coverage under the Equal Access Act, 20

U.S.C. §§ 4071-4074, in the wake of vociferous objections

15 This case law undermines the argument of some amici

that the "reasonable child" is "a creature unknown to the law."

Amicus Curiae Brief of Child Evangelism Fellowship, Inc. et al. at

9. Indeed, the "reasonable child" is a creature well known in tort

law. See, e.g., Restatement (Second) o f Torts § 464, at 507 (1965); see

also Capitol Square, 515 U.S. at 779-80 (O'Connor, J., concurring

in part and concurring in the judgm ent) (noting that "the

applicable observer [for Establishm ent Clause purposes] is

similar to the 'reasonable person' in tort law ").

23

from legislators that elementary school students would be

unable to distinguish private speech from school-spon

sored speech. See, e.g., S. Rep. No. 98-357, at 43-49 (1984),

reprinted in 1984 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2348, 2389-94; see also 130

Cong. Rec. S19231 (daily ed. June 27, 1984) (statements of

Sen. Metzenbaum and Sen. Hatfield); id. at H20934 (daily

ed. July 25, 1984) (statement of Rep. Schumer); cf. Mergens,

496 U.S. at 251 (plurality opinion) (noting that the Court

does "not lightly second-guess such legislative judgments,

particularly where the judgments are based in part on

empirical determinations"). A failure to recognize a dis

tinction between this case and Widmar and Mergens would

mark a significant retreat from these considered judgments

about the cognitive limitations of young children.

Petitioners' assertion that elementary school students'

impressionability is a "two way street" is wholly without

merit. See Pet. Br. 35; see also Laycock Br. 26-27. First and

foremost, it finds no support in the jurisprudence of this

Court. To the contrary, as the cases cited above demon

strate, this Court has long recognized that the "union

between church and state is most likely to influence chil

dren of tender years, whose experience is limited and

whose beliefs consequently are the function of environ

ment as much as of free and voluntary choice." Ball, 473

U.S. at 390. Second, it simply defies common sense to

argue that elementary school children would infer from

the fact that the Good News Club meets away from school

- as the Club once did, in a local church, see Pet. App. H2,

1 12 - that the Milford Central School is hostile toward

religion. To draw this conclusion, a student would have to

be aware, at a minimum, that the Good News Club sought

to meet at the school; that the school did not permit the

Good News Club to do so; that this decision was made

because the Good News Club is religious; and that the

school allows other, nonreligious groups and groups

merely with a religious perspective to meet at school. Only

a truly remarkable elementary school student - not the

benchmark reasonable student - would be aware of these

facts, let alone draw the insupportable inference from

24

these facts that the Milford Central School is hostile

toward religion. Such a remarkable student would no

doubt also be aware that the Establishment Clause manda

ted the school's decision, and thus that any such inference

was without foundation.

The age of the students in this case also undermines

petitioners' argument that the Milford Central School

could counteract any misimpression of endorsement

through some sort of disclaimer. See Pet. Br, 35-36. To be

sure, a plurality of this Court reasoned in Mergens that the

school board's "fear of a mistaken inference of endorse

ment is largely self-imposed, because the school itself has

control over any impressions it gives its students." 496

U.S. at 251 (plurality opinion). However, the plurality's

reasoning explicitly rested on the assumption that students

would "reasonably understand" a statement from the

school that its official recognition of the club "evinces

neutrality toward, rather than endorsement of, religious

speech." Id..; see also Capitol Square, 515 U.S. at 782 (O'Con

nor, J., concurring in part and concurring in the judgment)

(noting that "the reasonable observer . . . would certainly

be able to read and understand an adequate disclaimer"

(emphasis added)). Where, as here, the audience is incapa

ble even of reasonably understanding such a statement -

indeed, where such a statement would likely cause addi

tional confusion among the young children targeted - the

"fear of a mistaken inference of endorsement" is not self-

imposed, but rather unavoidable.

B. The Good News Club's Meetings Would Have

the Appearance of a School-Sponsored, After-

School Program

The probability that a reasonable elementary school

student would believe that the Good News Club meetings

were sponsored by the Milford Central School would be

greatly enhanced by the fact that those meetings would

take place in a classroom setting immediately after the end

of the formal school day. This factor is particularly salient

in today's world because many elementary school students

25

are effectively, if not actually, required to "attend" school

immediately after the "formal" school day. Accordingly,

allowing the Good News Club to meet at that time and in

that setting would be, for Establishment Clause purposes,

tantamount to allowing a religious group to conduct reli

gious worship, instruction and indoctrination during school

hours.

This Court has long been "particularly vigilant in

monitoring compliance with the Establishment Clause in

elementary and secondary schools." Edwards, 482 U.S. at

583-84; see id. at 584-85 (citing cases in which the Court has

invalidated statutes "which advance religion in public ele

mentary and secondary schools"); see also Lee, 505 U.S. at

592. Public schools hold a unique place among govern

ment institutions in Establishment Clause jurisprudence.

"Families entrust public schools with the education of

their children, but condition their trust on the understand

ing that the classroom will not purposely be used to

advance religious views that may conflict with the private

beliefs of the student and his or her family. Students in

such institutions are impressionable and their attendance

is involuntary." Edwards, 482 U.S. at 584.

The Court's vigilance has been particularly pro

nounced with respect to religious activities that take place

during the school day because such activities raise two

related, but distinct, concerns. First, as a result of manda

tory attendance requirements, the emulation of teachers

and peer pressure, such activities pose a high "risk of

compulsion." Lee, 505 U.S. at 596; see Edwards, 482 U.S. at

584; Wallace, 472 U.S. at 60 n.51; Schempp, 374 U.S. at 252-53

(Brennan, J., concurring); McCollum, 333 U.S. at 209-10.

Second, because such activities blur the line between pub

licly sponsored school activities and privately sponsored

religious activities, they heighten the probability that a

reasonable observer in the position of a student will

believe that the government is endorsing religion. As the

Court explained in Ball, "In this environment, the students

would be unlikely to discern the crucial difference

between the religious school classes and the 'public school'

26

classes, even if the latter were successfully kept free of

religious indoctrination." Ball, 473 U.S. at 391.

This case implicates both of these important concerns.

The Good News Club proposes to meet in a public school

classroom immediately after the end of the formal school

day, when students remain on school grounds by virtue of

the state's "compulsory education machinery." Lubbock

Civil Liberties Union v. Lubbock Indep. Sch. Dist., 669 F.2d

1038, 1046 (5th Cir. 1982). Thus, this case is a far cry from

Lamb's Chapel, in which a religious group sought to use a

public school auditorium or gymnasium between the

hours of 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. for the purpose of showing a

film series to adults. See Lamb's Chapel, 959 F.2d at 384; see

also Lamb's Chapel, 508 U.S. at 395 (relying in part on the

fact that the film series would not have been shown "dur

ing school hours" in concluding that the Establishment

Clause was not violated). Flere, unlike in Lamb's Chapel, an

objective elementary school student would have felt peer

pressure to attend the religious group's meetings - to join

his or her classmates as one of the "saved" by receiving

Jesus Christ as the Savior, not to mention also wanting to

receive candy and prizes - and would reasonably have

believed that the meetings were sponsored by the school

in which they were held.

To hold that the school day's ending bell alone makes

a difference for Establishment Clause purposes would, in

today's world, be "formalistic in the extreme." Lee, 505

U.S. at 595; see id. ("Law reaches past formalism."); see also

Santa Fe, 120 S. Ct. at 2280. Recent studies reveal that

almost 30% of public elementary schools and combined

primary-secondary schools now sponsor school-based,

extended-day programs. See, e.g., National Center for Edu

cation Statistics, Schools Serving Family Needs: Extended-Day

Programs in Public and Private Schools (U.S. Dep't of Educ.

Feb. 1997). See generally Patricia S. Seppanen et al., National

Study of Before & After School Programs (U.S. Dep't of Educ.

1993). Moreover, with the increasing labor force participa

tion of mothers with young children and the increasing

numbers of single-parent families, the need for - and,

27

consequently, the availability of - such programs is only

likely to grow. See, e.g., National Center for Education

Statistics, supra. Since the elementary school students who

attend these programs are incapable of leaving the school

premises on their own, many public school students are

effectively - if not actually - required to "attend" school

following the end of the "formal" school day.16 The Good

News Club in all likelihood wants to meet immediately

after the final bell sounds in order to include as many of

these young students as possible in its evangelical meet

ings. For these students, the Good News Club meetings in

public school classrooms would be no different than reli

gious classes in public school classrooms during (i.e., in

the final period of) the "formal" school day. Just as this

Court held the latter unconstitutional in 1948, see

McCollum, 333 U.S. at 209-10, it should leave no doubt that

the Good News Club meetings would be unconstitutional

today.

C. The Good News Club Would Be One of Only a

Few Private Groups Meeting on Public School

Premises

The presence or absence of a broad spectrum of pri

vate groups in a government forum is another important

factor in measuring a religious group's access to the forum

against the principles of the Establishment Clause. Thus,

for example, in Rosenberger, the religious student

newspaper "compete[dJ with 15 other magazines and

16 In M erg en s , the p lu ra lity fou nd c o n s titu tio n a lly

significant the Equal Access A ct's application only to student

meetings during what is clearly "noninstructional tim e." 496

U.S. at 251 (plurality opinion) (citing 20 U.S.C. § 4071(b)). For

high school students, who not only can organize their own

meetings but also are always able on their own accord to leave

sch o o l p re m ises a fte r sch o o l, the d is tin c tio n b e tw een

" in s tr u c t io n a l tim e " and "n o n in s tru c tio n a l tim e " is a

meaningful one. The same cannot be said for elementary school

students.

28

newspapers for advertising and readership/' 515 U.S. at

850 (O'Connor, J., concurring); in Capitol Square, the public

square was a "space in which a multiplicity of groups,

both secular and religious, engage[d] in expressive con

duct," 515 U.S. at 782 (O'Connor, J., concurring in part and

concurring in the judgment); in Lamb's Chapel, the school

property at issue was "heavily used by a wide variety of

private organizations," 508 U.S. at 392; in Mergens, there

was a "broad spectrum of officially recognized student

clubs" and "students [were] free to initiate and organize

additional student clubs," 496 U.S. at 252 (plurality opin

ion); and in Widmar, "the forum [was] available to a broad

class of nonreligious as well as religious speakers" - over

100 recognized student groups in all, 454 U.S. at 274.

In each of these cases, the vibrant nature of the gov

ernment forum weighed heavily against any appearance of

government endorsement. As justice O'Connor explained

in Rosenberger, "The widely divergent viewpoints of these

many purveyors of opinion, all supported on an equal

basis by the University, significantly diminishes the dan

ger that the message of any one publication is perceived as

endorsed by the University. . . . Given this wide array

of . . . viewpoints . . . , any perception that the University

endorses one particular viewpoint would be illogical." 515

U.S. at 850 (O'Connor, J., concurring); see Mergens, 496 U.S.

at 252 (plurality opinion) ("To the extent that a religious

club is merely one of many different student-initiated

voluntary clubs, students should perceive no message of

government endorsement of religion."); Widmar, 454 U.S.

at 274 ("The provision of benefits to so broad a spectrum

of groups is an important index of secular effect.").

In the present case, by contrast, any perception that

respondent endorses one particular group meeting on

school premises after school would be not only logical, but

well-nigh inescapable. An elementary school is not, like a

university or a public square, a forum designed for robust

intellectual debate and inquiry. Rather, it is "by . . . nature

and historical mandate a protected enclave for the regu

lated nurture of its students." Quappe v. Endry, 772 F. Supp.

29

1004, 1011 (S.D. Ohio 1991), aff’d, 979 F.2d 851 (6th Cir.

1992) (table). Consistent with this, only three private groups

apart from the Good News Club have met on respondent's

premises. See Pet. App. E4, % 21; Lodging at Yl-2, Zl,

AA3-4.17 Thus, there is no "broad spectrum" of officially

sanctioned private groups meeting at the Milford Central

School immediately after the end of the "formal" school

day. Mergens, 496 U.S. at 252 (plurality opinion). Instead,

the Good News Club would be one of only a few such

groups, and the danger that its message would be per

ceived as sponsored or endorsed by the school would be

grave indeed.

D. To Allow the Good News Club to Meet at the

Milford Central School Would Constitute an

Unprecedented Erosion of Establishment Clause

Values

This Court has repeatedly emphasized, in both word

and example, that "[e]very government practice must be

judged in its unique circumstances" to determine whether

it constitutes an endorsement of religion. Santa Fe, 120

S. Ct. at 2282 (internal quotation marks omitted); accord

Lee, 505 U.S. at 597. Only last Term, the Court cautioned

that in making such determinations, it is important to

"keep in mind the myriad, subtle ways in which Establish

ment Clause values can be eroded." Santa Fe, 120 S. Ct. at

2281 (internal quotation marks omitted). In light of the

17 Moreover, it is not clear from the record when these other

private groups meet on school grounds - that is, whether they

m eet im m ed iate ly after sch ool, as the Good N ew s Club

proposes to do, or whether they meet in the evening or on

weekends. Thus, it may be that the Good News Club would be

the only outside group meeting on school grounds immediately

after the "form al" school day. Cf. M ergens, 496 U.S. at 252

(plurality opinion) ("To the extent that a religious club is merely

one o f many different . . . clubs, students should perceive no

message of government endorsement of religion." (emphasis

added)).

30

unique circumstances discussed above, and the fundamen