Correspondence from Blacksher to Judge Thompson

Public Court Documents

March 19, 1986

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Correspondence from Blacksher to Judge Thompson, 1986. 4208707d-b8d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/80028de9-9a69-4fda-b7b5-d91a3b6fd4bf/correspondence-from-blacksher-to-judge-thompson. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Copied!

i # » } ov

Nee

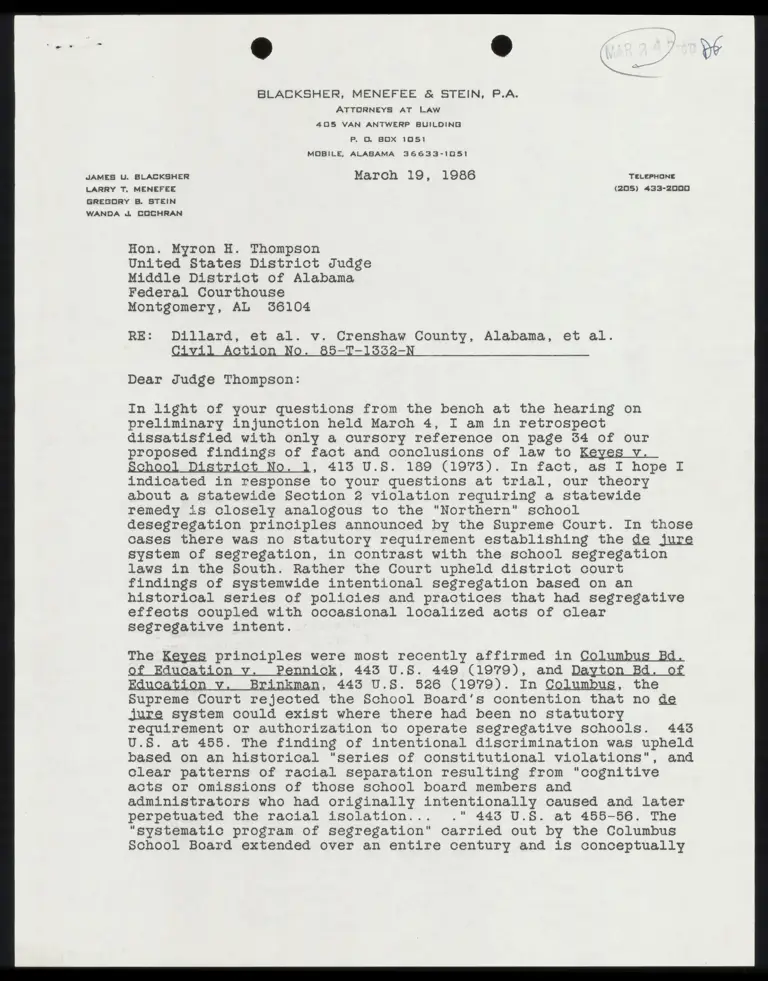

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

405 VAN ANTWERP BUILDING

PF. O. BOX 1051

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36633-10851

JAMES U. BLACKSHER March 19, 1986 TELEPHONE

LARRY T. MENEFEE (205) 433-2000

GREGORY B. STEIN

WANDA J. COCHRAN

Hon. Myron H. Thompson

United States District Judge

Middle District of Alabama

Federal Courthouse

Montgomery, AL 36104

RE: Dillard, et al. v. Crenshaw County, Alabama, et al.

Civil Action No. 85-T-1332—N

Dear Judge Thompson:

In light of your questions from the bench at the hearing on

preliminary injunction held March 4, I am in retrospect

dissatisfied with only a cursory reference on page 34 of our

proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law to

School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973). In fact, as I hope I

indicated in response to your questions at trial, our theory

about a statewide Section 2 violation requiring a statewide

remedy is closely analogous to the "Northern" school

desegregation principles announced by the Supreme Court. In those

cases there was no statutory requirement establishing the de Jjure

system of segregation, in contrast with the school segregation

laws in the South. Rather the Court upheld district court

findings of systemwide intentional segregation based on an

historical series of policies and practices that had segregative

effects coupled with occasional localized acts of clear

segregative intent.

The Keyes principles were most recently affirmed in Columbus Bd.

of Education v. Pennick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979), and t

Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979). In Columbus, the

Supreme Court rejected the School Board's contention that no de

Jure system could exist where there had been no statutory

requirement or authorization to operate segregative schools. 443

U.S. at 455. The finding of intentional discrimination was upheld

based on an historical "series of constitutional violations", and

clear patterns of racial separation resulting from "cognitive

acts or omissions of those school board members and

administrators who had originally intentionally caused and later

perpetuated the racial isolation... ." 443 U.S. at 455-586. The

“systematic program of segregation" carried out by the Columbus

School Board extended over an entire century and is conceptually

Hon. Myron H. Thompson

March 19, 1986

Page Two

indistinguishable from the systematic program of manipulation of

the at-large election systems for county commissions conducted

for over a century by the Alabama Legislature. See 443 U.S. at

456. The Court held that it was not necessary for the Columbus

plaintiffs to demonstrate that "all schools were wholly black or

wholly white in 1954... ." 443 U.S. at 456. Instead, "[plroof of

purposeful and effective maintenance of a body of separate black

schools in a gubstantial part of the system itself is prima facie

proof of a dual school system and supports a finding to this

effect absent sufficient contrary proof by the Board, which was

not forthcoming in this case." 443 U.S. at 458 (emphasis

added).

Equally significant were the findings in Dayton, where the

establishment of two or three one-race schools through the

history of the school system was found to be highly probative of

systemwide racial motives, particularly when coupled with the

weight of all the historical practices and policies. The Supreme

Court approved the district court’s conclusion that the School

Board’'s "intentional segregative practices cannot be confined in

one distinct area"; they "infected the entire Dayton public

school system." 443 U.S. at 536-37. Thus, the patterns of proof

of intentional racial discrimination in these northern school

desegregation cases parallel the proof in the instant case: a

series of policies and practices in particular historical

contexts that had clear racial impact throughout the jurisdiction

controlled by the decisionmakers whose motives were in question;

localized instances of clear racial intent that confirm the

inferences supplied by the historical patterns; and a strong

national mandate to dismantle the vestiges of historical

segregation. The case for systematic, historical, racially

discriminatory motives on the part of the Alabama Legislature is

even clearer in the instant case than in the northern school

desegregation cases, because we have produced "smoking gun”

statements connected with the 1953 anti-single shot law and the

1961 numbered post law.

An additional point from Keyes, Columbus and Dayton is the

requirement that the jurisdiction found guilty of intentional

segregation proceed immediately to dismantle the discriminatory

system root and branch. The duty to dismantle extends throughout

the system, even where no localized acts of discrimination have

been demonstrated. E.g., Dayton, supra, 443 U.S. at 537.

Hon. Myron H. Thompson

March 19, 1986

Page Three

In light of Congress’ purpose in 1982 amending the Voting Rights

Act, the national mandate for elimination of all vestiges of

discriminatory structures that dilute black voting strength is

just as strong as the national mandate to desegregate the

schools.

Best regards.

Very respectfully,

BLACKSHER, a

s

‘Japes U. Blacksher

: WP

CC All Counsel

STEIN, P. A.