Judgment

Public Court Documents

April 13, 1984

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman v. Lambert and Wilder v. Lambert Court Documents. Judgment, 1984. 5eb9a214-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/82916136-7bcb-4052-8e82-34cff7c48ea0/judgment. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

o

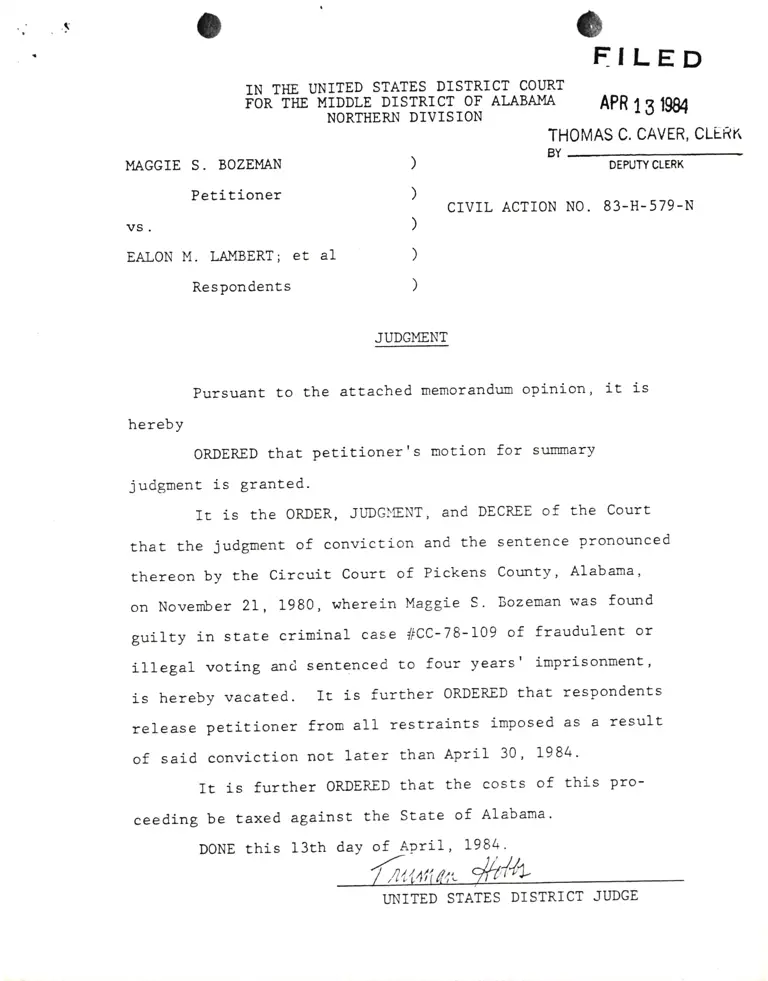

F ILED

MAGGIE S. BOZEMAN

Petitioner

vs.

EALON M. LAI'{BERT; et a1

Respondents

CIVIL ACTION

APR t g tS4

THOMAS C. CAVER, CLER/T

BY

DEPUTY CLERK

N0. 83-H-579-N

IN T}IE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Fon rrc MTDDLE DrsrRrcr oF AI-ABAUA

NORTHERN DIVISION

)

)

)

)

)

JUDGMENT

Pursuant to the attached memorandr:m opinion, it is

hereby

oRDERED that petitioner's rnotion for sumnary

judgment is granted.

II iS thc OR.DER, JIIDG}ENT, ANd DECREE Of thc COUTT

that the judgment of conviction and the sentence pronounced

thereon by the Circuit Court of Pickens Cor:nty, Alabama,

on November 2L,1980, wherein Maggie s. Bozeman was found

guilty in stat.e criminal case llCC-78-I09 of fraudulent or

illegal voting anci sentenced to four years' imprisonment,

is hereby vacated. It is further ORDERED that respondents

release petitioner from aII restraints inposed as a result

of said conviction not later than April 30, 1984.

It is further oRDERED that the costs of this Pro-

ceeding be taxed against the State of Alabama '

DONE this 13th daY of APriI, 1984'

4ourrr'. #/1t

I]NITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

o

E ILED

ApR 1g 1984

THOMAS C. CAVER, CLEH(

BY

DEPUTY CLERK

) crvrl AcTroN NO. 83-H-579-N

EALON M. LAI'IBERT; et al )

Respondents

JI]LIA P. WILDER )

Petitioner )

vs. ) crvrl ACrroN No. 83-H-580-N

EALON M. I-AMBERT; et aI )

Respondents )

MEI.{ORANDUM OPINION

This cause is before the Court on petitioners' motions

for summary judgrment. Although the court has not

consolidateC these cases, it will issue a joint opinion,

with separate judgirnents. Bozeman in her motion argues that,

under Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307 (1979), the evidence

was insufficient to suPport her conviction. She also

contends that she was deprived of her constitutional right

to notice of the charges against her. Wilder raises only

the latter claim in her motion. She raises the Jackson

claim in her petition, however, and the Court thus will

consider it now. For the reasons stated below, the Court

MAGGIE S. BOZEMAN

Petitioner

vs.

IN THE IJNITED STATES DISTRICT COI'RT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF AI.ABAMA

NORTTIERN DIVISION

)

)

finds for both

Bozeman on her

petitioners on their notice claims and for

Jackson claim.

FACTS

Both petitioners were convicted under a statute

proscribing voting more than once or voting when one is not

entitled to do so, in connection with their participation in

the casting of absentee ballots in the Democratic primary

runoff on September 26, 1978 in Pickens County. The

contention of the prosecution was, essentially, that

petitioners procured absentee ballots in the names of

registered voters and voted the ballots themselves.

Specifically, the prosecution contended that petitioners

would take applications for absentee ballots around to

elderly blacks and ask them if they wanted to be able to

vote without going to the poI1s. l"lost of these elderly

people were. illiterate, so petitioners ordinarily would help

them fill it out, and the voter would make an lrx* mark-

Sometimes the application would direct that the ballot be

mailed to the voter and sometimes to one of three addresses.

Wilder's address was among the three; Bozeman's was not.

Either petitioners or the voter would turn the applications

for an absentee baIlot in to the Pickens County Clerk's

office. According to the prosecution, Petitioners obtained

thirty-nine of these ballots, fil}ed them out, and signed

the registered voters' names to them. Wilder and Bozeman.

took the ballots to a notary public, who notarized them uPon

-2

petitioners' assurance that the signatures were va1id. The

ballots were subsequentlY voted.

When a court clerk noticed that all- of the absentee

ballot applications turned in by Wilder had one of three

addresses on them, she notified her superior, who contacted

the District Attorney. The District Attorney had the box

containing the absentee ballots inspected, and it was

discovered that thirty-nine ballots had been notarized by

Paul Ro11ins, a notary in Tuscaloosa. A11 thirty-nine

ballots were voted identically, and none was signed with an

"x, " even though many of the corresponding applications

were. Some of the corresPonding aPPlications had one of the

three addresses on them, and some did not. Wilder witnessed

some of the applications that were signed with an "x";

Bozeman did not witness any.

I. EVIDENCE OF WILDERIS GUILT

The Court has thoroughly reviewed the record of

Wilder's trial. Given that the Alabama Court of Criminal

Appeals set out the testimony at hrilder's trial in its

opinion, and given that this Court finds that the evidence

clearly was sufficient under Jackson to convict Wilder,

there is no need for this Court to go beyond the Court of

Criminal Appeals' review of the evidence.

II. EVIDENCE OF BOZEMANIS GUILT

The Court will detail the testimony at Bozeman's trial.

The witnesses included nine elderly blacks whose votes were

3

among those removed from the box. Not one of the elderly

voters testified that Bozeman ever came to See him or her

about voting in connection with the runoff. l{ost of their

testimony concerned Wilder's activities. Also, none of the

voters had any knowledge of Paul Rol1ins, the notary public

who notarized their baIlots.

Janice Ti]Iey, the court c]erk, t€stified that Bozeman

came in several times to pick up applications for absentee

ba]lots. This was entirely 1egaI. She also stated that one

time, just prior to the runof f , Bozeman and l^lj-Ider came

together in a car, although only Wilder came into the

office. upon objections by defense counsel, however, the

trial judge struck most of this testimony, including all

references to Wilder. The only testimony that was not

stricken was that Bozeman was in a car alone and did not

come inside.

The state also presented evidence gertaining to the

opening of the baIlot box and the removal of thirty-nine

ballots notar j-zed by Paul Rollins.

Paul Rollins testified that he notarized some ballots

for the runoff election in TuscaLoosa. He stated that

Wilder, Bozeman, and two or three other ladies brought the

ballots. He refused to say that Bozeman herself asked him

to notarize the ba]lots, testifying instead that the group

did, and that the grouP represented that the signatures were

genuine after he told them that the signators were supposed

to be present. He also stated that he received two ca1ls to

set up the meeting, but that he could not remember whether

-L

Bozeman made either caII. He later testified, however, that

Bozeman made one call pertaining to some baIlots, but he was

not sure which ballots. Fina}ly, he testified that he went

to Pickens County to notarize a second set of ballots, and

that he believed this occurred at the general election.

Maudine Latham testified that she signed an application

that was brought to her by Clemmie Grice and his wife, but

that she was not told what it was. she stated that she

never saw a baIIot, or Bozeman.

Annie Billups testified that wilder made an rtxrr on her

application, and also filIed out her ballot with her

consent. She was unsure whether Wilder read the names,

although she stated that viilder told her who the blacks were

voting for. Bozeman was not Present at either of these

times.

I"lattie Gipson testified that she made an rtxfl on an

application that hrilder brought her, but that she never got

a ballot. She then testified, however, that Minnie Hill

brought her a ba]Iot, and that she put her mark on it- Her

ballot bears no mark. She also stated that Wilder at some

point showed her a sample ballot indicating for whom the

blacks were voting. she stated that Bozeman had no

connection to any of these events '

Nat Dancey testified that he did not remember anything

about either the apPlication or the balIot. He stated that

he could not have signed the ballot because he could not

E

write. He denied ever telling Bozeman anything about

voting.

Janie Richey testified that she "sometimes" writes her

name and that she did not remember making the rrxrr that

appears on her aPPlication, although she remembered Wilder

bringing the application to her.. She testified first that a

ba1lot came in the maiI, and then that "they brought" one to

her. The prosecutor read her notes of an interview in which

she denied ever getting a ballot, but she still maintained

on the stand that she received a ba110t. The notes were not

admitted into evidence. on cross-examination, she testified

that hrilder told her who the blacks were voting for, and

that l,iilder marked her ba1lot with her consent. she stated

that she never spoke with Bozeman about voting.

Pronnie Rice testified that she fi11ed out and signed

both her application and her ballot. She stuck to this story

when the prosecutor read to her from a deposition in which

she denied ever receiving a baI1ot. Her application had her

own address on it. She also testified that Bozeman had

nothing to do with her voting activities'

Lou Sommerville testified that she was unsure whether

she had filled out an application. Her testimony as to irer

baIlot was simply incomprehensible. After the judge

declared her a hostile witness, the prosecution read to her

from a deposition in which she stated that Bozeman helped

her fill out an application. she stated in the deposition

that she never saw Bozeman after she fill-ec out the

-6

application, although she also stated that Bozeman may have

fil]ed in her ballot and that she never signed the ballot.

Her application bears her own address. on the stand, she

testified that Bozeman had never signed anything for her.

She also denied ever having named Bozeman at the deposition.

In fact, she denied ever giving a deposition. The deposition

was not admitted into evidence-

Sophia Spann testified that she did not sign an

application or a baI]ot. She also stated that when she went

to her usual polling pIace, she was told that her absentee

baIlot had been cast. She stated that Bozeman came at some

time prior to the runoff and asked if Spann wanted to vote

absentee, and Spann said she did not- Julia Wilder

witnessed Spann's aPPlication.

Lucille Harris testified that she signed an aPplication

that Wilder brought to her. She further testified that she

never signed or received a balIot, although her own address

appeared on the application. She stated that Bozeman had

nothing to do with her voting activities'

DISCUSSION

SufficiencY of the Evidence

Both petitioners assert that the evidence at their

trials was insufficient to suPPort their convj-ctions within

the meaning of Jackson v. virginia, 4A3 u.s. 307 (L979). In

-7

Jackson, the Supreme Court held that habeas corpus relief is

available where the evidence at trial is such that, viewed

in a light most favorable to the prosecutionr rro "rational

trier of fact could have found the essential elements of the

crime beyond a reasonable doubt." Id. 319. The Court

explicitly rejected a standard under which only a showing of

"no evidence" of guilt would establish a due process

violation. Id. at 320i see Thompson v. Lousiville, 352 U.S.

199 (1960). Thus, a mere "modicum" of evidence is

insufficient . 443 U. S. at 320.

In applying the Jackson standard, courts first examine

state law to determine the elements of the crime. Duncan v.

Stynchcombe, 704 F.2d 1213, \214-15 (11th Cir. 1983);

Holloway v. McEIroy, 632 F.2d 505, 640 (5th Cir. 1980),

cert. denied, 451 U.S. 1028 (1981). In determining whether

the evidence established those elements, the court may not

resol-ve issues of credibility. Duncan, 704 F.2d at 1215-

Thus, where the evidence conflicts the court must presume

that the jury accepted the prosecution's version, and must

defer to that result. 443 U.S. at 326.

Petitioners were convicted of violating S 17-23-1.

That section provides that "Ia]ny Person who'votes more than

once at any election held in this state, or deposits more

than one ba1Iot for the same office as his vote at such

election, or knowingly attempts to vote when he is not

entitled to do sor or is guilty of any kind of i11ega1 or

fraudulent voting" is guilty of a crime. Under Alabama case

-8

1aw, rr

of the

Wilder

the words' i1Iega1 or fraudulent' . . .are. . -descriptive

intent necessary for the commission of the offense."

v. State,401 So.2d 15I, 159 (AIa.Cr-App.), cert.

.is voting more than once,I' Wilson v. State, 52

303 (1875), or voting when the voter is not

to do so. Wilder, 40I So.2d at 160.

denied, 401 So.2d 167 (1981). "The offense denounced by the

statute. .

AIa. 299,

entitled

A. Viilder

The evidence was sufficient for a rational jury to find

Wilder guilty. A significant amount of evidence indicated

that ballots were cast in the names of people who denied

casting them, and sufficient evidence linked ldilder to those

ballots. Wilder picked up numerous applications, she took

them to the persons whose votes were purportedly "Sto]enr"

she had access to many of the ba}lots, and she was in the

group that took them to Rollins to be notarized. A jury

could reasonably find beyond a reasonable doubt that wilder

must have fi1Ied in the ballots herself and cast them with

the intent of voting more than once.

B. Bozeman

Bozeman's case iS quite different. The only evidence

against Bozeman was Rollins' testimony that she was one of

the ladies who brought the ballots to be notarized, that she

may have ca]led to arrange the meeting, and that the ladies

as a group represented the ballots to be genuine after he

told them that the signators were supposed to be present.

The only other possj.ble indications of guilt were either

-9

stricken or were ruled inad.missible. All of the court

clerk's testimony tending to show that Bozeman came with

Wilder to deposit !h. ballots was stricken, and Lou

Sommerville's deposition was never placed in evidence and

would not have been admissible as substantive evidence

an) da)r.

Although there was conrrincing evioence to show that the

ballots were i1leqaI1y cast, there was no evidence of intent

on Bozeman's part and no evidence that she forged or helped

to forge the baIlots. There is no evidence that she took

applications to any of the voters, or that she helped any of

the voters fill out an application or ballot, or that she

returned an aPplication or baIlot for any of the voters, and

no batlot was mailed to her residence. Thus, there was no

evidence that Bozemarr realj-zed when she accomPanied Wilder

and others to the office of Ro11i-ns that the ballots that

she helped to get notarized were fraudulent'

This case is somevrhat analogous to the cases holding

that " [m] ere Presence in an area where unlawful drugs are

discovered is insufficient to support a conviction for drug

possession." united states v. Rackley, No. 82-6020, slip

op. at 1502 (1lth Cir. Feb. 13, 1984) (citing United States

v. Rojas, 537 F.2d 216, 220 (5th Cir. 1976), cert denied,

42g v. s.1051 (1977))- The standard in such cases is

similar to that in Jackson. United States v' Sanders, 639

F.2d 268, 270 (5th Cir. 1981) (where "reasonable Persons

might find the evidence inconsistent with every reasonable

-10

hypothesis of innocence" ) . The only distinction between

this case and Rackley is that there was evidence that

Bozeman had at least constructive possession of the ballots.

Constructive Possession of narcotics will suPPort a

conviction. Rackley, slip op. at 1502; United States v.

Hernandez, 484 F.2d 85, 87 (5th Cir. 1973). This

oistinction is not decisive, however. It should be plain to

anybody possessing cocaine that the substance is illega],

but it would not necessarily be so with forged bal]ots.

Thus, the inference that Bozeman intentionally took part j-n

forging the ballots cannot be drawn from her constructive

possession of them when she was at the notary's office in

the company of Wilder and others-

Respondents' reliance on aiding and abetting also is

not justified. They asserted at oral argument that the

evidence showed Wilder to be gui1ty and Bozeman to have

aided her. Even under that theory, however, there still

was no evidence of intent. There was no evidence to negate

the inference that Bozeman was just going along with what

she believed to be an innocent effort to have absentee

ballots cast. The evidence did not show Bozeman to have

played any role in the process of ordering, co11ecting, or

filling out the ballots. The record also lacks any evidence

of any contact between Bozeman and l,lilder except at the

notary's. Thus, there is no evj-dence to indicate that

Bozeman knew the ballots to be fraudulent'

-II

II. NOTICE

Petitioners claim that the indictments were

constitutionally defective in that they failed to provide

the notice reguired by the Sixth Amendment. The indictments,

which hrere identical, charged that each petitioner--

COUNT ONE

did vote more than once, or did deposit

more than one ballot for the same office

as her vote, or did vote i11ega11Y or

fraudulently, in the Democratic Primary

Run-off Election of September 26,1978,

COUNT TWO

did vote more than once as an absentee

voter, or did dePosit more than one

absentee baI1ot for the same office

or offices as her vote, or did cast

illegal or fraudulent absentee ballots,

in the Democratic PrimarY Run-off

Electj-on of SePtember 26, 1978,

COUNT THREE

did cast illegaI or fraudulent absentee

ballots in the Democratic Primary Run-

off Election of SePtember 26, 1978,

in that she did deposit with the Pickens

County Circuit Clerk, absentee ballots

which were fraudulent and which she knew

to be fraudulent.

Petitioners raise three challenges to the indictment' They

contend that the trial judge instructed the jurj-es on

several Statutes not contained in the indictment, thus

allowing the juries to convict petitioners on charges of

which they had no notice. Petitioners also contend that the

indictments were constitutionally defective because the

factual allegations were inSufficient and because necessary

elements of the crime were omitted'

-L2

A. Habeas Review of Challenges to Indictments

As an initial matter, the Court rejects

respondents' argument that habeas petitioners may not

challenge the sufficiency of a state indictment. Respondents

rely on cases in which petitioners challenged the

sufficiency of indictments under state ]aw. Johnson v.

Estelle, 704 F.2d 232, 236 (5th Cir. 1983); Cramer v'

Fahner, 683 F.2d 1376, 1381-82 (7th Cir. 1982), cert'

denied, U. S. (1983) ; DeBenedictis v- Wainwright, 674

F.2d 841, 843 (lIth Cir. 1982); Branch v. Este11e, 631 F.2d

I22g, !233 (5th Cir. 1980). Where an indictment abridges a

constitutional guarantee, habeas is available. Cramer, 583

F.2d at 1381; cf. Hance v. Zant,696 F.2d 940,953 (lIth

Cir. 1983) ; Washington v- Vlatkins, 655 F' 2d 1346, 1359 (5th

Cir. 1981), cert. denied, 456 U-S. 949 (1982) ' Furthermore'

in Plunkett v. Estel]e, 709 F.2d 1OO4 (5th Cir. 1983), the

court considered a claim that the jury charge allowed a

conviction of a crime not charged, id. at 1009, a claim

petitioners raise here. Thus, petitioners here may challenge

the indictments insofar as their challenge constitutes an

+j,.

attack upon the notice provided by the indictments.

B. Instruction Upon Statutes not Charged in

the lndictmencs

The Court rejects respondents' contention that, because

petitioners failed to object to the jury instructions, they

waived any objection to the inclusion therein of offenses

not charged in the indictments. see l'iainwright v. sykes,

-13

433 U.S. 72 (1977); Brazell v. State,423 So.2d 323,326

(AIa.cr.App. 1982). First, wilder's attorneys did object to

the inclusion of the statutes on perjury and notarization.

Second, the Court believes that petitioners' claim is a

challenge to the lack of notice and not to the jury charges.

Had the indictments charged the offenses included in the

instructions, the latter would have been unobjectionable.

The Fifth Circuit, in Plunkett v. Este1le, 709 F.2d lO04,

1008 (5th Cir. 1984), rejected a construction similar to the

one respondents urge here. Furthermore, the Alabama courts

consider the right to notice as so fundamental that

objections to the lack of notice cannot be waived. 8.g.,

Barbee v. State, 417 So.2d 611, 513 (AIa.Cr.App .1982) ;

Edwards v. State, 379 So-2d 336, 338 (AIa.Cr.App.L979);

cert. denied, 379 So.2d 339 (1980). The Court does not

believe the Alabama courts would bar petitioners from

asserting this issue on "pp".fl/ Thus, the Court holds that

petitioners have not waived this cIaim.

Petitioners argue that the trial court's jury

instructions allowed them to be found guilty of charges upon

which they were not indicted. The indictments charged

petitioners with voting more than once or voting

"fraudulently or i1lega1Iy" or casting "fraudulent or

1 . The Alabana cor-nts would not, ho\,never, consider this claim on collateral

:ievievr, ard thus it presents no exhaustion problm. As the CoLrt stated in its

order denying respondents' rction to dismiss, this claim is not cognizable cn:r

collateral reviar il Alabana, &d habeas corpus reviss also is not available in

Alabana to parolees. Fr:::the:rpre, petitioners clai:red lack of notice on apoeal,

atthougfr they did not raise the specific issue they raise here.

-L4

iI1ega1" baIlots. The trial court defined "iIIegaI" by

instructing the jury on four statutes not contained in the

indictment. The trial judge first explained Ala. Code S

17-I0-3, which describes what persons are eligible to vote

absentee. He then read AIa. Code S 17-10-6, which requires

that absentee ballots be s\dorn to before a notary public,

with certain exceptions. The judge then instructed the

juries on AIa. Code S 17-10-7, which provides that absentee

voters must appear personally before the notary. Fina1ly,

the judge charged the jury that, under A1a. Code S 13-5-115,

any person who falsely and corruptly makes a sworn statement

in connection with an election is guilty of Perjury.

Petitioners argue that the instructions allowed them to be

conr"'icted of any violations of these statutes.

As a general rule, a conviction based upon a charge not

contained in the indictment violates due ProceSS. Jackson

v. Virginia, 443 U. S. 307, 314 (1979) ("ft is axiomatic

that a conviction upon a cha.rge not made or a charge not

tried constitutes a denial of due process-"); CoIe v.

Arkansas, 333 U.S. 195, zOL (1948) ("ft is as much a

violation of due Process to send an accused to prison

following conviction of a charge on which he was never tried

as it would be to convict him upon a charge that was never

made."); DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353, 362 (1937)

("Conviction upon a charge not m.ade would be sheer denial

due process."); see Dunn v. United States, 442 U.S. 100,

(1979). Furthermore, an indictment must a1Iege every

of

106

-15

(l

essential element of the violation charged therein. Hamling

v. United States,4!8 U.S.87, 117 (1974); Russell v. United

States, 359 U.S. 749, 771 (1962); United States v. Outler,

659 F.2d 1306, 1310 (5th Cir. Unit B 1981), cert. denied,

455 U.S. 950 (1982); United States v. varkonyi,645 F.2d

453, 455 (5th Cir. 19BI).

The Eighth Circuit has upheld a claim similar to

petitioners'. In Goodloe v. Parratt, 605 F.2d 1041 (8th Cir.

1979), petitioner was charged with "unlawfulIy operatIing] a

motor vehicle to flee in such vehicle in an effort to avoid

arrest for violating any 1aw of this State. " The State

originally claimed at trial that petitioner had fled to

avoid arrest for driving with a suspended license, although

he had earlier been acguitted of that charge. The trial

court ru}ed, however, that the State had to show an actual

violation, so the State altered its contentions to reckless

driving. Id. at 1044-45. The Eighth circuit ruled that,

" [o] nce prior violation of a specific statute became an

element of the offense by virtue of the trial court ruling,

Goodloe was entitled not only to notice of that general

fact, but also to specific notice of what 1aw he was alleged

to have violated." Id. at 1045. The information under

which petitioner was charged thus "failed to adequately

describe the offense charged because it did not aIlege an

essential substantive e1ement." Id. at 1046. The court

went on to note that, if petitioner had had actual notice of

the State's contentions, due process would have been met

-16

,'Q

despite the inadequacy of the information. The arrest

warrant had notified petitioner of the suspended license

charge, but the Staters switch in tactics deprived him of

due process. Id.; accord, l{atson v. Jago, 558 F.2d 330 (6th

Cir. 1977).

The Fifth circuit recently has followed the basic

approach of watson and Goocloe. In PlunkeLt, the Fifth

Circuit found a constitutional violation where petitioner

was charged with intentionally causing a death, and the

trial court added to its instructions a charge on causing

death by an act intended to cause serious bodily injury.

The trial court, in summing up its statements of abstract

1aw by applying the 1aw to the facts of the case, used only

the language of the correct statute. 709 F.2d at 1007' The

Fifth circuit reasoned that the charge must be considered in

light of the entire triaI, and examined the Prosecutor's

closing argument as well as the charge. The court found

that the prosecutor told the jury that petitioner could be

found guilty under the non-charged definition of murder'

rd. at 1008-09. The court found that, given the evidence

and theories presented by the parties, the jury could have

concluded that petitioner intended to injure but not ki11

the victim, and thus the jury could have convicted him of

the non-charged offense. Id. at 10I0-11; gf:cord, Tarpley v'

Estel1e, 703 F.2d L57, 159-6I (5th Cir' 1983) '

To summarize, the correct approach is to determine

whether the jury could reasonably have convicted either

-t7

petitioner of a crime not charged in the indictment. The

determination reguires an examination of the trial as a

who1e, including the charge, the arguments and theories of

the parties, and the evidence. The case Iaw further makes

clear that the fact that there may have been sufficient

evidence to convict on the crime that was charged is not

sufficient to sustain the convi-ction.

Respondents argue that the jurry instructions did not

al1ow i{i1der to be convicted under the non-charged statutes.

They point to pages 311 and 3L2 of the transcript, at which

the court instructed in essence that the State was charging

Wilder with voting more than once, and with marking the

absentee ballots without the voters' consent. The court

concluded that, "Such a ballot would be ilIegaI to cast a

bal1ot [sic] or participate in the scheme to cast that

ballot with knowledge of these facts and would faII within

the acts prohibited by Section 17-3-1 [sic] of the Alabama

Code of 1975." Thus, resPondents conclude, liilder must have

been convicted of violating the statute under which she was

charged.

Respondents' argument is patently wrong. Respondents

ignore the paragraph immediately following the one quoted

above:

Further, the State charges that the defendant

witnessed or had knowledge that a Notary

Public falsely notarized or attested to the

authenticity of the ballots by attesting the

persons before him and so forth as provided

in the affidavit. If the ballot was falsely

attested to, then such a ballot would be

itlegal and any Person who participated in

-18

a scheme to cast that ballot with knowledge

of that fact would commit the acts prohibited

by Section 17-3-1 [sic] of the Alabama Code

of 1975 if in fact that balIot was cast.

Tr. 312. Thus, the court's charge explicitly permitted the

jury to convict Wilder with casting an improperly notarized

ba}}ot, a crime with which she was not charged. Wilder went

into court expecting to face a charge that she voted more

than once, and yet the jury was told that it was enough for

the prosecution to show the ballots were improperly

notarized, even if they were otherwise valid.

The evidence in the case was such that the jury could

have convicted l^lilder on the charge of which she had no

notice. I^lilder testif ied that the voters either f ilIed out

their own ballots or authorized her to fill them out. Thus,

if the jury believed Wilder, it could have found that htilder

did not cast two or more ballots as her own vote but that

she did cast improperly notarized bal1ots, and hence was

guilty under the court's charge.

Bozeman has a slightly stronger claim on this issue

than l{i1der. The trial court did not.summarize the Staters

contentions as it did in hrilder's case. It simply

instructed the jury, ds in I'iilder' s case, that

"i1lega1...means an act that is not authorized by law or is

contrary to the ]awr" tr.2O!, and then charged on the four

statutes not contained in the indictment. As in Wilder's

case, this would lead a reasonable juror to believe that

Bozeman could be convicted of casting improperly notarized

ballots. This would have especially prejudiced Bozeman

-19

committed one or more statutory wrongs in the notarization

of the bal]ots.2/ There is a world of difference between

forging a person's baIlot and failing to fol1ow the proper

procedure in getting that Personrs ballot notarized. If

petitioners were facing the latter charge, they had a right

to be toId. They were not. To put it simply, petitioners

were tried upon charges that were never made and of which

they were never notified. Thus, their convictions cannot

stand.

2. Another source of potential prejudice to petitioners

was the conflicting ways in which the Alabama courts have

interpreted the term "iIlegal. " According to the Court of

Criminal Appeals, it simply describes the intent necessary

to a violation of S 17-23-L, Wilder, 401 So.2d at 160. Ttre

trial court, ho\nrever, gave the term a life of its own. That

cour! charged the juries that "illegal. . .means an act that

is not authorized by 1aw or is contrary to the law." Thus,

as petitioners point out, aIl laws pertaining to voting

becane incorporated into S 17-23-L. Under the interpre-

tation of the Court of Criminal Appeals, this would be

incorrect, and improper notarization would not be a crime

r:rrder S 17-23-L. Yet the trial court's instructions made it

one.

-2t

C. Insufficient Factual and Legal Alleoations

The Court rejects petitioners' claim that the

indictments failed adequately'to notify them of the charge

that they voted more than once. "The validity of an

indictment is determined from reading the indictment as a

wholer...and...must be determined by practical, not

technical, considerations." United States v. Markham, 537

F.2d 187, 192 (5th Cir. 1975), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 1041

(19771; see United gtates v. Outler, 659 F.2d 1305, 1310-11

(5th Cir. Unit B 1981), cert denied,455 U-S- 950 (1982);

United States v. Uni OiI, Inc., 545 F.2d 946, 954 (5th Cir.

1981), cert. denied, 455 u.s. 908 (1982)t United States v.

Decidue, 503 r.2d 535, 545 (5th Cir. 1979), cert. denied,

445 U.S. 945, 446 U.S. 912 (1980); United states v. c1ark,

546 F.2d 1130, 1132 (5th Cir. L977). rwo of the counts

accused petitioners of voting more than once, and two

specified absentee bal}ots. A11 three counts accused

petitioners of voting fraudulently or i11egally. Although

the indictments are flawed if read literaIly, they contained

sufficient information to notify petitioners of the charge

of voting more than once. Furthermore, petitionerS could

employ the entire records in pleading double jeopardy in a

later case. Russe1l, 359 U.S. at 764.

-22

The Court does, however, find that petitioners'

sixth Amendment rights were violated because they were tried

for offenses with which they were never charged, and that

Bozeman's conviction violated Jackson v. Virginia. Because

of the latter finding, the Double Jeopardy Clause prevents

the State from retrying Bozeman, Burks v. United States, 437

u.s. 1 (1978), and the writ as to her shaII issue at once.

The state frdy, however, retry wilder, Greene v.l"lassey, 437

U.S. 19 (1978), and the Court will al1ow it ninety days in

which to do so.

Separate judgments will be entered in accordance with

this memorandum oPinion.

DONE this t3th daY of APri1, 1984'

6*"'^ /

I]NITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

-23