Lani Guinier: The Civil Rights Litigator Who “Dared to Be Powerful”

By Carrie Hagen, Narrative Writer, Thurgood Marshall Institute

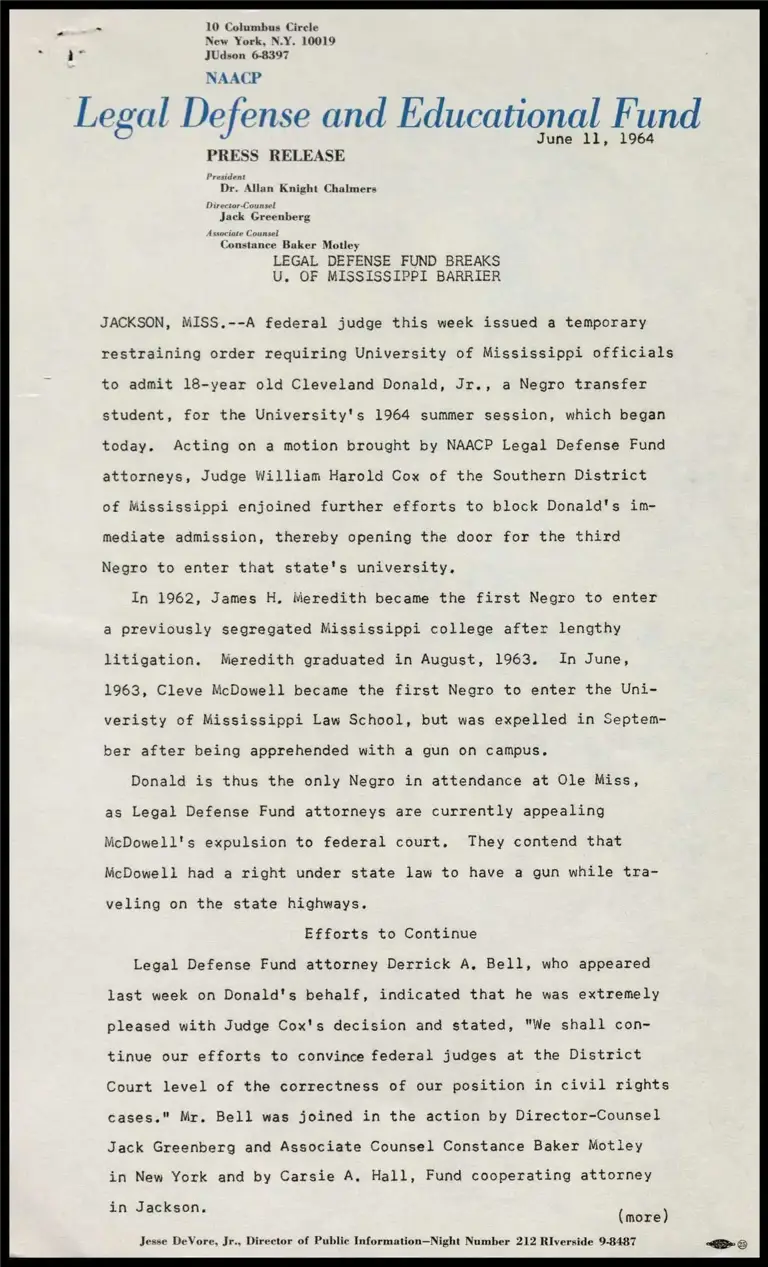

In early October 1962, 12-year-old Lani Guinier watched on her family’s black-and-white television as Legal Defense Fund (LDF) civil rights attorney Constance Baker Motley accompanied her client, Air Force veteran James Meredith, through angry protesters on the streets of Oxford, Mississippi. Meredith had filed a racial discrimination suit against the University of Mississippi, and on September 10, 1962, his lawyers at LDF won the suit on appeal to the nation’s highest court. Pursuant to the mandate of Brown v. Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the integration of “Ole Miss,” provoking an armed protest. Between September 30 and October 1, 1962, President John F. Kennedy deployed 30,000 U.S. Army troops to patrol Oxford as 29-year-old Meredith registered for classes. Federal marshals served as a personal protective detail for Meredith’s legal team, which included Motley and LDF Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg.

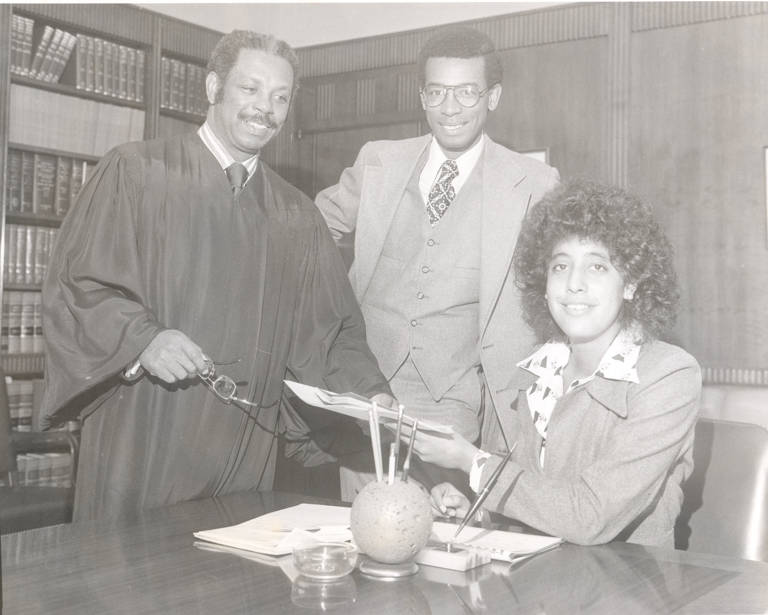

Lani Guinier (right) with the Honorable Damon J. Keith (far left) and James Coleman (middle). Guinier clerked for Judge Keith on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit from August 1974 to August 1976.

At home in Queens, New York, where she lived with her two sisters, her white Jewish mother, and her Black father, Guinier watched the news footage that captured scenes from the race riots in Oxford. Protesters threw rocks, bottles, and bricks at the marshals, and National Guardsmen released tear gas into the crowds. Juxtaposed with these violent images were scenes of Meredith, a slender Black man with a mustache, who wore a suit and hat as he calmly walked between Motley and Greenberg through the upheaval.

Legal Defense Fund Breaks U. Mississippi Barrier

“The town of Oxford is an armed camp, following riots that accompanied the registration of the first Negro in the university’s 118-year history,” said Universal-International News journalist Ed Herlihy in a newsreel. Reporting that rioters had attacked his cameraman and destroyed additional footage, Herlihy called the moment “the greatest crisis the South has faced since the Civil War.” In an appeal from the White House, President Kennedy asked students and state authorities to comply peacefully, saying, “Americans are free and sure to disagree with the law, but not to disobey it.” By the end of October 1, 1962, the rioting had killed two people, wounded more than 300, and led to the arrest of approximately 200 protesters.

The image of Motley so inspired Guinier that she decided to become a civil rights lawyer herself one day. Decades later, when Guinier accepted an honorary doctorate from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 2004, she recalled how impressed she was by the “tall, dignified Black woman” on her television: “I thought, ‘I believe I can do that, too.’ I believed I could do that, because I saw in Constance Motley’s erect stance a woman who dared to be powerful.”

Guinier’s honorary degree from the University of Illinois was just one of many accomplishments in her own long career as a civil rights lawyer and the first Black woman to gain tenure at Harvard Law School. In the 1990s, she too would stand before a bank of television cameras, but in a moment of stinging political defeat—after a U.S. president who had nominated her for a senior Justice Department post reversed course and branded her civil rights scholarship, written over the course of her academic career, as “antidemocratic.” The racism and sexism that were on full display during that episode underscored the continuing struggle for civil rights and equality.

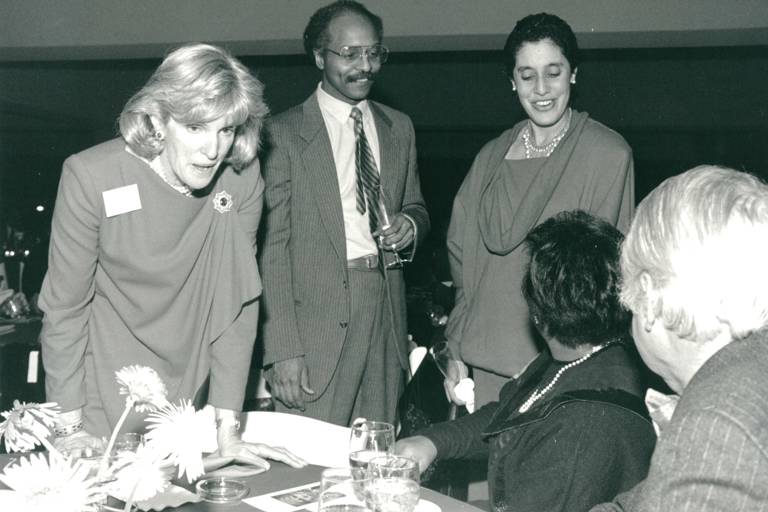

Lani Guinier, standing at right, speaks with colleagues at a dinner.

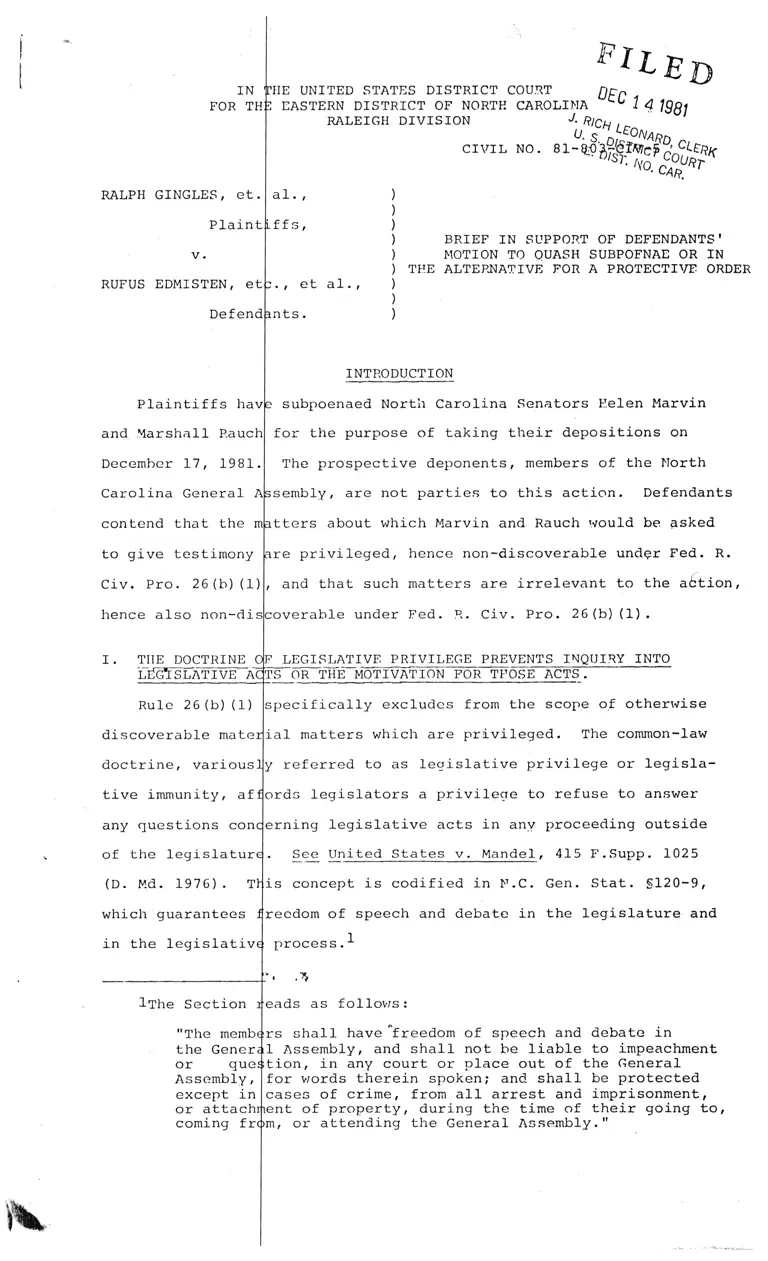

Walking in Motley’s footsteps, Guinier joined LDF as Assistant Counsel in April 1981. A graduate of Radcliffe College (1971) and Yale Law School (1974), she first served in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice (DOJ) in the Carter administration as Special Assistant to Assistant Attorney General Drew Days. During her seven years at LDF, Guinier became a top litigator and led the organization’s groundbreaking voting rights work. She litigated major voting rights cases throughout the South along with other important civil rights cases, winning 31 of 32 cases she argued. Among her many legal victories, Guinier and her teams successfully challenged: Louisiana’s racially biased redistricting plans that deprived Black voters of the right to participate in the electoral process (Major v. Treen, 1983); the voting fraud convictions of Black civil rights activists in Alabama (Bozeman v. Lambert and Wilder v. Lambert, 1984 and 1985); North Carolina’s redistricting plan that illegally diluted Black voting strength (Thornburg v. Gingles, 1986); and Alabama state laws that discriminated against Black voters and limited their voting access (Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 1986).

Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae; Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae

Guinier left LDF in 1988 to become a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and in 1998, she became the first tenured woman of color at Harvard Law School. An expert on voting rights and civil rights, an award-winning educator, and a prolific writer, Guinier died of complications of dementia at age 71 in January 2022.

Speaking with The New York Times after Guinier’s passing, Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s then-President and Director-Counsel, remarked on Guinier’s legacy: “She was easily one of the most innovative thinkers in the voting rights space.”

Becoming a Top Voting Rights Litigator

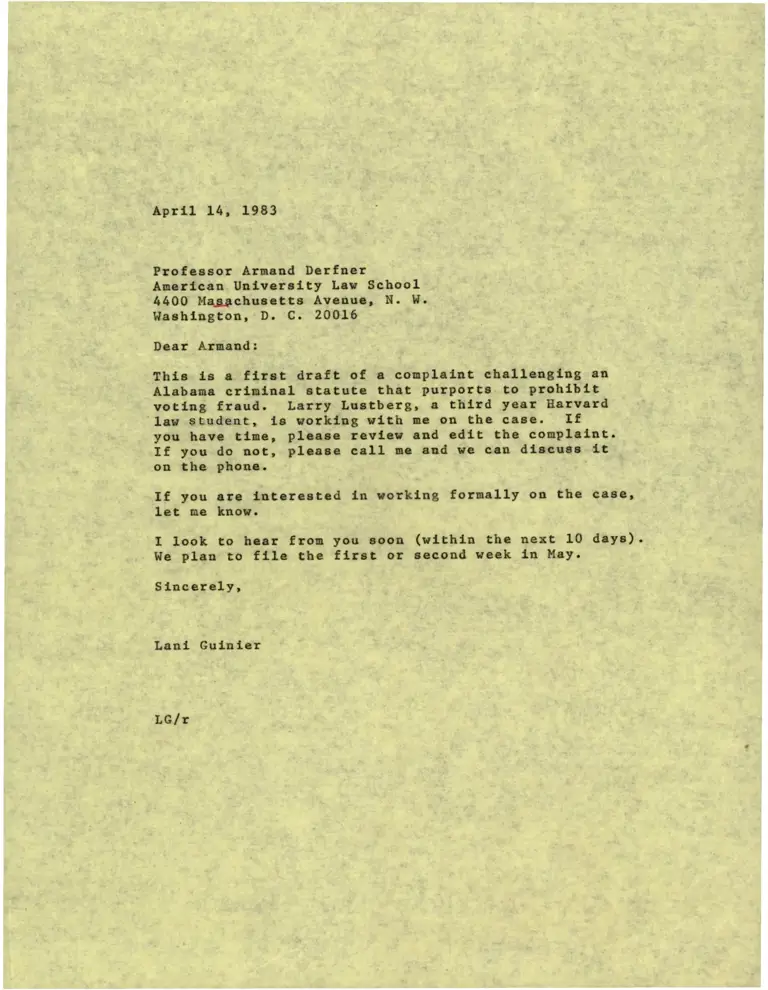

Correspondence from Guinier to Derfner

"I was doing the Lord’s work, I thought, when I became a voting rights lawyer." – Lani Guinier

Guinier’s vital work to defend voting rights in the United States began on her first day at LDF in April 1981. Her first assignment was to work with attorney (and LDF’s future President and Director-Counsel) Elaine Jones on the legislative battle to extend and amend the Voting Rights Act of 1965. If Congress did not pass an extension, key provisions of the act were set to expire.

“I was doing the Lord’s work, I thought, when I became a voting rights lawyer,” Guinier later wrote in her memoir, Lift Every Voice.

At the start of 1982, LDF Director-Counsel Greenberg approached Guinier regarding a recent story in The New York Times about a voter fraud case in Pickens County, Alabama, in which an all-white jury delivered a guilty verdict against two Black women. Greenberg suspected that the women—Maggie Bozeman, a 51-year-old teacher and president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and Julia Wilder, a 69-year-old officer of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference—had been falsely accused.

Pickens County’s population was 42% Black, yet voters there had never elected a Black person to county office. It also had a significant elderly population who struggled with voting laws that restricted access to polling places. Bozeman and Wilder facilitated Black elders’ voting participation through absentee ballots. Similar to civil rights activists in other rural Southern areas, they actively sought to empower Black voters to submit absentee ballots. Their organizing worked, and the increased political participation by Black voters in Pickens County helped secure improvements like paved roads and better wages for sanitation workers. White authorities took note.

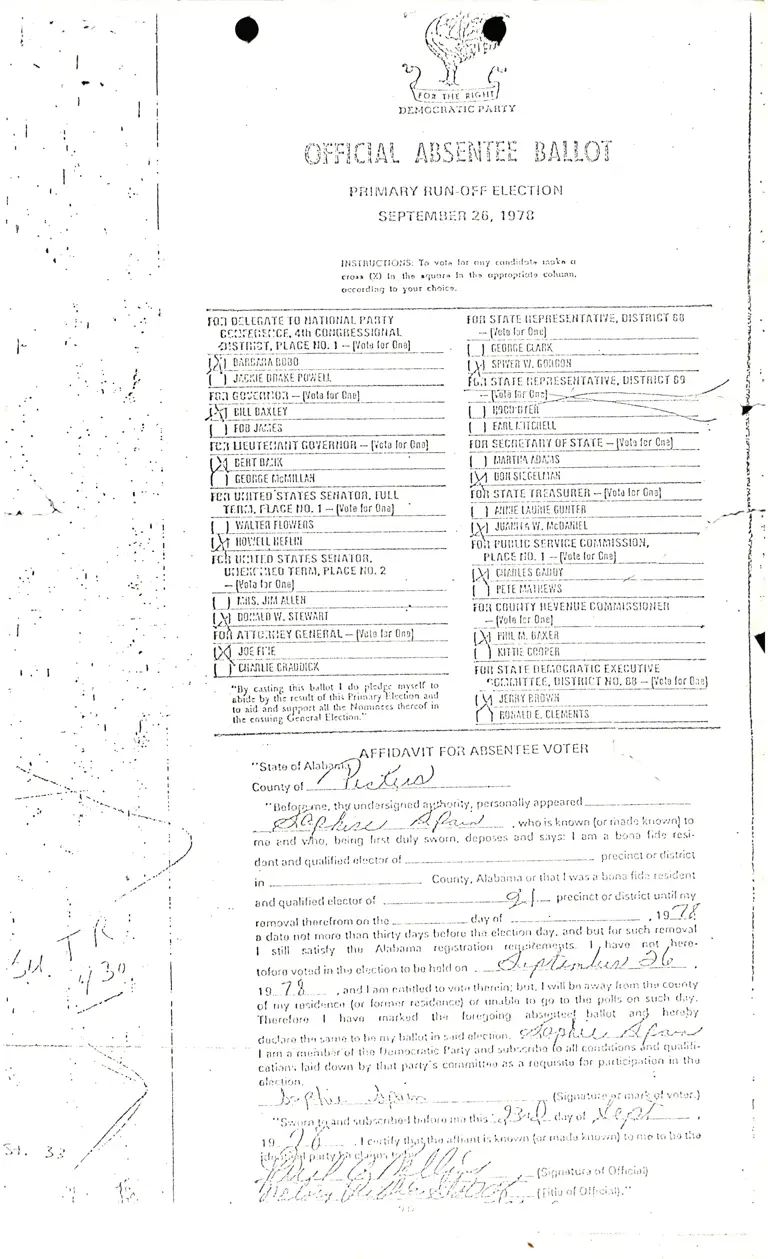

Official Absentee Ballot and Affidavit for Absentee Voter

For the 1978 county elections, Bozeman and Wilder assisted more than three dozen Black elders with their absentee ballots. They helped absentee voters complete, notarize, and mail their ballots to the County Election Commission. However, when one of the absentee voters also tried to cast her vote in person on Election Day, the local district attorney launched an investigation that led to convictions for Bozeman and Wilder on charges of voting fraud and forging absentee ballots. The prosecution’s case exploited the frail memories and vulnerabilities of Black elders who had lived through decades of voter intimidation. After an all-white jury convicted the women, the state court judge sentenced Bozeman to four years in prison and Wilder to five years, the maximum penalty.

“The sentences are believed to be the stiffest ever given in an Alabama voting fraud case,” wrote The Washington Post.

An Alabama appeals court panel upheld the verdict, even as it questioned the prosecution’s case and called the trial testimony “confusing and conflicting.” The Supreme Court of Alabama and the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear further appeals.

As Greenberg read in the Times, on January 12, 1982, the women appeared before an Alabama Circuit Court judge with a last-minute plea for leniency. Approximately 300 spectators, mostly Black, filled the courthouse in Carrollton, Alabama, to hear 15 character witnesses testify for the defense. When Judge Clatus Junkin rejected the plea, the courtroom burst into an uproar and spectators clung to Bozeman and Wilder. Joining arms, the crowd turned their cries into the singing of “We Shall Not Be Moved.” Alabama State Troopers, called to Carrollton to support local police, separated the women from supporters’ clenched hands and led them into custody.

“Just get these convictions overturned,” Greenberg told 31-year-old Guinier.

Having served in the Civil Rights Division of the DOJ during the Carter administration, Guinier knew that Black leaders had complained for years about white authorities abusing the rules of the electoral process. Finding no evidence that Bozeman or Wilder had engaged in fraudulent activity, LDF’s team filed habeas corpus petitions challenging the women’s incarceration and convictions.

Meanwhile, the civil rights community in Pickens County mobilized to make sure that the nation saw what was happening there. On February 7, 1982, more than 300 Southern civil rights workers and supporters started a 140-mile protest march from the courthouse in Carrollton to the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery. The 13-day march would be the longest in the South since 1965, when Black people mobilized to secure their constitutional right to vote by marching along the 54-mile highway between Selma and Montgomery. Just as the 1965 marches contributed to the passage of the Voting Rights Act, the march in February 1982 spurred not only the release of Bozeman and Wilder, but also the extension of the Voting Rights Act.

Over two weeks, in temperatures at times below freezing, marchers linked arms, chanted, and sang spirituals. Journalists and police estimated that between 3,500 and 5,000 people arrived in Montgomery on February 19, 1982, at least 50 of whom had marched the full 140 miles between Carrollton and Montgomery. The marchers were accompanied by five people who had marched in Selma in 1965, including recently elected Atlanta City Councilman John Lewis.

"I came back today with a sense of hope and determination that we are on the verge of building a new movement," John Lewis told reporters.

The historic 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery March.

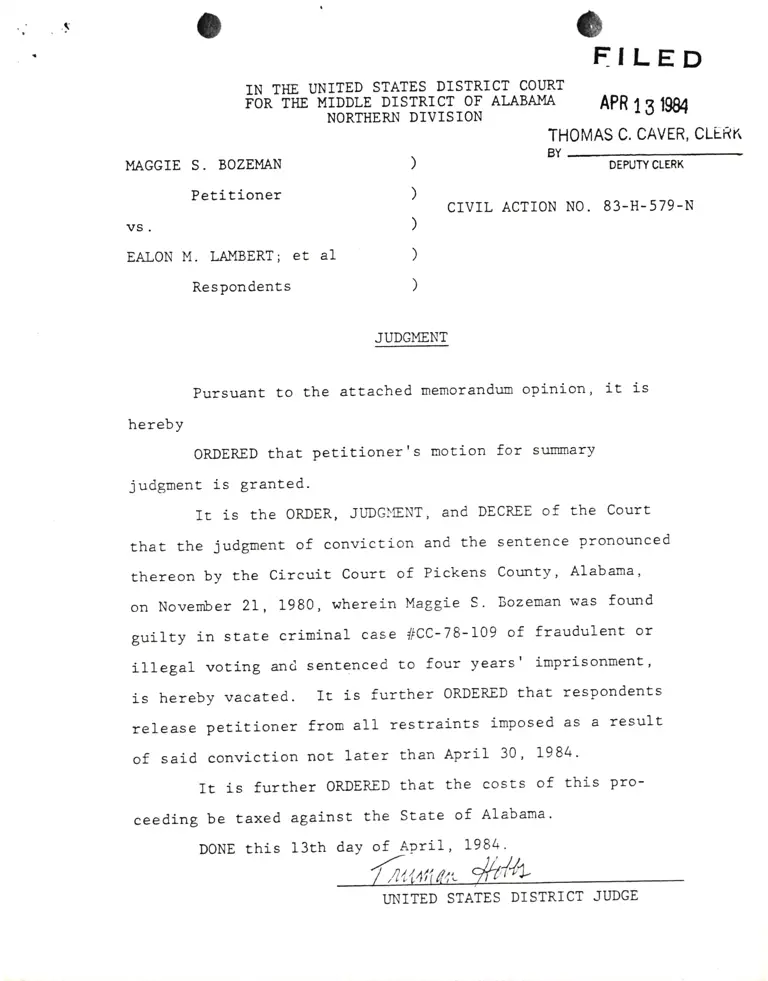

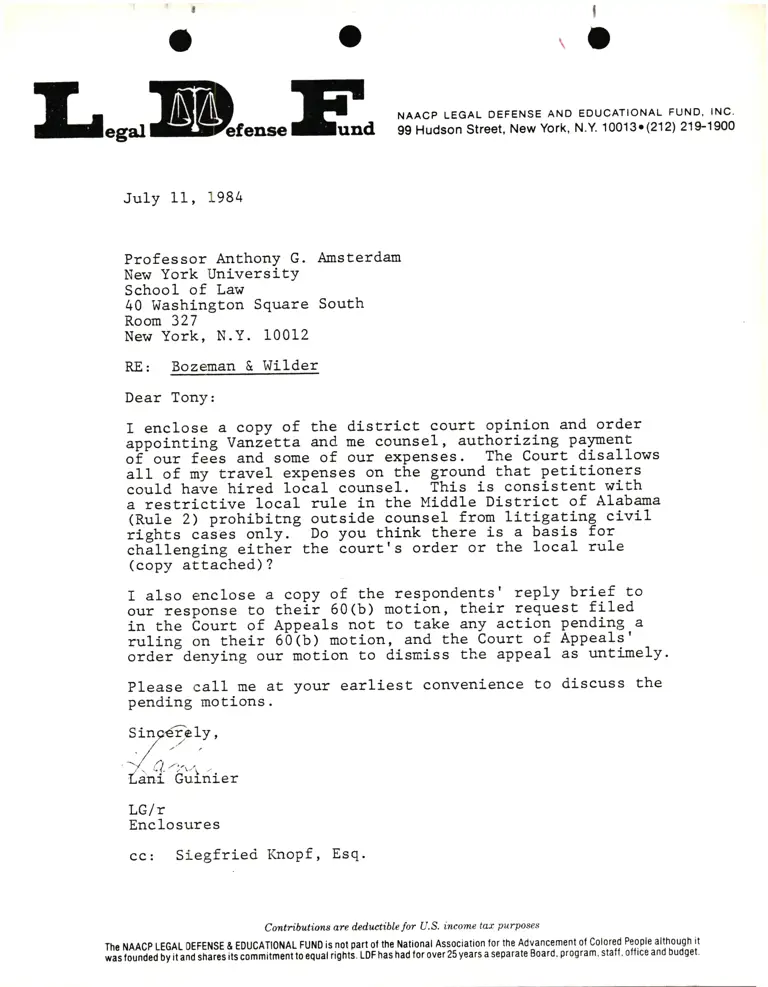

Six months after the 1982 march on Montgomery, Congress passed the extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, including provisions to protect key parts of the law abolishing discriminatory election practices. In November 1982, the Alabama State Board of Pardons and Paroles voted unanimously to grant parole to Bozeman and Wilder. Finally, in April 1984, Guinier and LDF secured a victory for the women in Bozeman v. Lambert and Wilder v. Lambert when a federal judge overturned their convictions, ruling that they were “improperly tried by the state” and that their Sixth Amendment rights had been violated because the accusations against them were not fully outlined until after the defense rested its case. Although the local district attorney appealed this decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit upheld the ruling in May 1985.

Judgment

Correspondence from Guinier to Amsterdam

The February 1982 march was an example of a mobilized civil rights constituency. Guinier later reflected that she did not have the same mobilized support for her failed 1993 nomination to become Assistant Attorney General of Civil Rights for the DOJ. In the latter fight, Guinier would experience the disillusionment of a political outsider unable to rally what she called “sympathetic insiders” to her cause.

A Political Outsider in the Clinton Years

In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated Guinier for the Civil Rights job because, he said, “There had never been a full-time practicing civil rights lawyer with a career in civil rights law heading the Civil Rights Division.” Almost immediately, conservative detractors began pressuring the president to withdraw her name, citing purportedly controversial theories she had explored in her legal scholarly writings. Guinier focused much of her scholarship as a professor on advocating for voter reform. During her time at the University of Pennsylvania, her publications in academic legal journals put forward progressive legal theories about the discriminatory nature of “winner take all majority rule.” She argued that single-winner elections honor the popular vote, but often disregard minority representation. Guinier’s scholarship considered how to create electoral laws and reform government systems to include greater minority representation.

Critics—who often admitted to have not read the entirety of her work—alleged that her ideas were too “radical” for government office. When libertarian Clint Bolick wrote an opinion piece for The Wall Street Journal on April 30, 1993, branding Guinier as a “quota queen,” the name stuck, at least among her critics. By selectively taking sentences from Guinier’s legal arguments out of context, conservative legislators and journalists spun an image of a radicalized, undemocratic woman.

Guinier wanted the opportunity to talk to her critics and to assure politicians that her legal writings would not translate into policy. Clinton’s aides, however, dissuaded her from privately meeting with legislators to garner support. The controversy over Guinier’s nomination would require the president to make a divisive political decision that would anger either leftist liberals or centrists and conservatives. As the administration prepared for budget and health care debates, it chose to invest its resources and time into lobbying for these issues instead of Guinier’s nomination. Not wanting Guinier’s self-advocacy to thwart their agenda, Clinton’s communications team asked her to refrain from making any comments. She watched as the president reassessed her candidacy while her public image became a composite of misrepresentations and buzzwords like “quota queen.”

"I was simply remade," Guinier reflected in her book Lift Every Voice. "An elite group of opinion molders depersonalized and demonized me."

Lani Guinier (left) and Bill Clinton (right)

In a press conference on June 3, 1993, President Clinton praised Guinier as a civil rights attorney but withdrew her nomination and referred to her legal thoughts as “antidemocratic.” This label drew the ire of the civil rights community. The following day, she was defended in The New York Times by William T. Coleman Jr., former president of LDF’s Board of Directors and the Secretary of Transportation under President Gerald Ford. “She is superbly qualified, mainstream, and pro-integrationist in the tradition of Thurgood Marshall,” Coleman, a Black Republican, wrote. “Guinier clearly believes in majority rule; she simply questions whether democracy and fairness are served when a racially defined majority monopolizes power.” Coleman questioned whether even Marshall himself could have been confirmed in such a hostile climate, writing, “Thurgood Marshall’s successors, such as Lani Guinier, should not be condemned for working through the system to reverse the lingering effects of 200 years of slavery and another 100 years of segregation.”

Initially devastated by President Clinton’s withdrawal of her nomination, Guinier later said the experience “freed” her to more fully embrace her progressive ideas as she returned to teaching and academic writing. In her memoir, she even assumed a degree of responsibility for her failed nomination because she had allowed political polarization, and political complacency, to keep her from forcing the conversations about democracy that she wanted to have with members of the Senate. As an LDF lawyer, she had repeatedly seen the power of conversations among “ordinary people” that started grassroots movements and “mobilized civil rights advocacy.” It was such a movement that helped her team overturn the convictions of Bozeman and Wilder.

“I momentarily lost the perspective I had had in 1981 and 1982, when I worked with a creative and contentious group of litigators and lobbyists to extend and amend the Voting Rights Act,” she wrote. “I forgot the strategic role outsiders played in creating synergy and holding insiders accountable.”

In a press conference covered by C-SPAN on June 4, 1993, one day after President Clinton’s decision to pull her nomination, 43-year-old Guinier said she was “greatly disappointed.” In front of a nation that had largely learned of her name through the critics who had disparaged it, she defended her candidacy with her husband and her son at her side. Viewers watching at home saw a Black civil rights activist standing with poise and grace during a chaotic moment. Looking into the cameras, Guinier “dared to be powerful” while responding to her critics, as she had observed Constance Baker Motley doing three decades before.

“I have always believed in democracy, and nothing I have ever written is inconsistent with that,” she said. She lamented what she perceived as a possible cultural shift in political debate, saying, “I hope that we are not witnessing the dawning of a new intellectual orthodoxy in which thoughtful people can no longer debate provocative ideas without denying the country their talents as public servants.”

Five years later, Guinier became Harvard Law School’s first tenured woman of color. At Harvard, as at the University of Pennsylvania, Guinier further developed and discussed the provocative ideas that now define her legacy as a legal scholar, including the need for “candid public discourse” over implicit bias, social constructs, and race and gender discrimination in politics, the classroom, the workplace, and the law.