Cosner v. Dalton Interlocutory Order; Elam v. Dalton, Common Cause v. Lustig, Gravely v. Dalton, Beville v. Dalton, Farraday v. Dalton, and Ely v. Anderson Opinion

Public Court Documents

August 25, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Cosner v. Dalton Interlocutory Order; Elam v. Dalton, Common Cause v. Lustig, Gravely v. Dalton, Beville v. Dalton, Farraday v. Dalton, and Ely v. Anderson Opinion, 1981. a5702af2-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/85f60ccf-c9b9-4f38-a610-0343a450f3ad/cosner-v-dalton-interlocutory-order-elam-v-dalton-common-cause-v-lustig-gravely-v-dalton-beville-v-dalton-farraday-v-dalton-and-ely-v-anderson-opinion. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

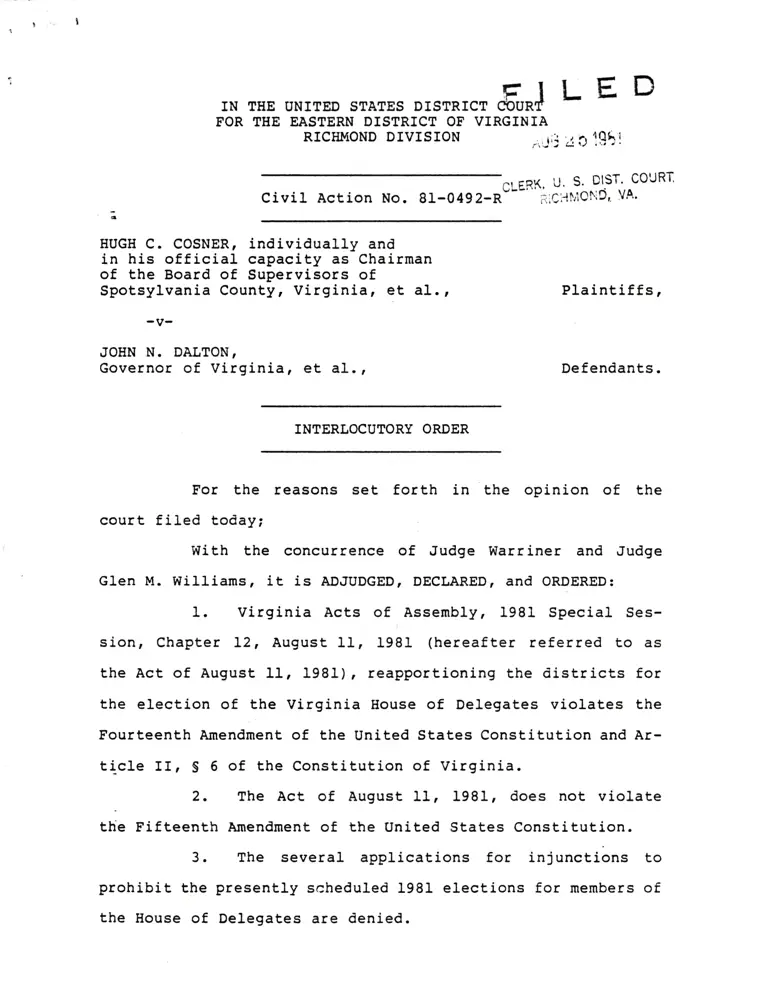

rN rHE uNrrED srArEs DrsrRrc, E *.1 L E D

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

RICH!{OND DMSION ;,,_t;j "j

l,: 1-af !

t t t * *i' j"'?;'?l]t'ol

o u Rr

4

HUGH C. COSNER, individually and

in his official capacity as Chairman

of the Board of Supervisors of

Spotsylvania County, Virginiar €t aI. r PJ.aintiffs,

-v-

JOHN N. DALTON,

Governor of Virginiar €t aI., Defendants.

INTERLOCUTORY ORDER

For the reasons set forth in the opinion of the

court filed today;

With the concurrence of Judge Warriner and Judge

Glen M. Willians, it is ADJUDGED, DECLARED, and ORDERED:

1. Virginia Acts of Assembly, 1981 Special Ses-

sion, Chapter L2, August 11, 1981 (hereafter referred to as

the Act of August 11, 1981), reapportioning the districts for

the election of the Virginia House of Delegates violates the

Pourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution and Ar-

ti-cle II, S 6 of the Constitution of Virginia.

. The Act of August 11, 1981, does not violate

the Fifteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution.

3. The several applications for injunctions to

prohibit the presently scheduled 1981 elections for members of

the House of Delegates are denied.

4. The defendants, Wayne Lustig, Chairman, State

Board of Elections; Willis 11[. Anderson, Vice-Chairman, State

Board of Elections; and Joan S. l'Iahan, Secretof,Y, State Board

of Elections (hereafter referred to as the Officers of the

Slate Board of Elections), and each of them, t,heir successors

in office, their agents and employees, and all persons in ac-

tive concert or participation with them who receive actual no-

tice of this order by personal service or otherwise are en-

joined and restrained from certifying candidates and conduct-

ing any election for the House of Delegates pursuant to the

Act of August 11, 198I, except as provided in the next Para-

graph of this order.

5. The Officers of the State Board of Elections

are authorized to certify candidates and conduct an election

for the House of Delegates pursuant to the Act of August 1I,

1981; provided, however, that each member of the House of Del-

egates elected in 1981 shalI serve for a term of one year.

This term shall beginr ES presently provided in Virginia Code

S 24.1-11 (1980), on the second Wednesday in January, L982.

The Officers of the State Board of Elections sha1l certify

that members of the House of Delegates elected in 1981 shal1

serve for a term of one year as provided in this order.

. Unless otherwise provided by further order of

this court, the Officers of the State Board of Elections are

directed to perform all acts required by 1aw, including but

not limited to holding prinary elections, for the elect.ion of

members to the House of Delegates at the regularly scheduled

general election in November, L982. The General Assenbly of

Virginia may provide by law on or before February 1, L9A2,

whether the members of the House of Delegates elected in 1982

shall serve for a term of one or two years. rf the General

Aqsembly does not exercise this option, the term of nembers of

the llouse of Deregates elected in L982 shalI be for one year

to begin as presently provided by Iaw.

7. Consideration of the requests of several par-

ties for this court to reapportion the districts for the House

of Delegates is deferred until after February I, 1982.

8. On or before February I, Lgg2, the General As-

sembly of Virginia may reapportion the districts for the House

of Delegates in conforrnity with the constitutions of the

united states and virginia. The reapportionment Act must be

forthwith submitted to the Attorney Generar of the united

States pursuant to the Voting Rights Act of 19G5 and a copy

filed with the court.

9. Within 30 days after the enactment of a nee, re-

apportionment plan, but not later than February 15, tgg2, each

party who requests reapportionment by the court sharr submit a

plan of reapportionment. Each submission must comply with the

following directions set forth in chapman v. Meier, 420 u.s.

L, _25-27 (1975) :

[U] nless there are persuasive justifications, a- court-ordered reapportionment plan of a state leg-' islature must avoid use of multimember districts,

and, as welI, must ordinarily achieve the goal ofpopulation equality with little more than de minimis

var iation.

Any party whose plan departs fron these standards must "artic-

ulate precisery why a plan of single-member districts with

3-

./

nlnlual populatlon varlance cannot be adoptcd.' {20 U.S. at

27.

10. Rccclpt of a copy of, this order by eounacl C,ot

the defcndantg ghall conrtltutc sufflclcnt servlcc on thc de-

fqndante and cach of thca.

For thc court:

/s/ John D. Butzncr, iIE.

John D. Butznsr, Jr.

Unltcd States Clrcult Judgc

Auguet 25, 198t

3 orclock P.t{.

4

,t

a

IN TEE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR TEE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

RICHMOND DIVISION

CiviL Action No. 81-0492-R

HUGH C. COSNER, individually and

in his official capacity as Chairnan

of the Board of Supervisors of

Spotsylvania County, Virginia;

EDDIE W. CHEWNING, individually

and in his official capacity as a

Supervisor of Spotsylvania

County, Virginia;

l{. E. HICKS, individually and

in his official capacity as a

Supervisor of Spotsylvania

County, Virginia;

EII{MITT B. MARSHALL, iNdiVidUAllY

and in his official capacity as

a Supervisor of Spotsylvania

County, Virginia;

ANDREW H. SEAY, individually and

in his official capacity as

Supervisor of Spotsylvania

County, Virginia, Plaintiffs.

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF

HANOVER COUNTY, VIRGINIA; Plaintiff-Intervenor.

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF

CIIESTERFIELD COUNTY, VIRGINIA; Plaintif f-fntervenor.

-v-

JOHN N. DALTON,

Governor of Virginia;

WAYNE LUSTIG, Chairman,

State Board of Elections;

WILLIS M. ANDERSON, Vice-Chairman, '

St,ate Board of Elections;

JOAN S. MAHAN, Secretdry,

State Board of Elections;

rt

JAII4ES B. SMITE, Chairman,

Spotsylvania County Electoral Board;

JAMES D. BLAKE, Secretdty,

Spotsylvania County Electoral Board;

EVELYN STRAUGHAN, Menber t .

Spotsylvania County Electoral Board t Defendants.

KATHLEEN K. SEEFELDT, individually

and in her official capacity as

Chairman of the Board of County

Supervisors of Prince William -

County, Virginia;

DONALD t. WHITE, individually

and in his official capacity as a

member of the Board of County

Supervisors of Prince Willian

County, Virginia;

JOSEPH D. READING, individually

and in his official capacity as

a menber of the Board of County

Supervisors of Prince William

County, Virginia;

RICHARD G. PFITZNER, individually

and in his official capacity as a

menber of the Board of County

Supervisors of Prince William

County, Virginia; and

JAI'{ES J. McCOART, individually

and in his official capacity as

a member of the Board of County

Supervisors of Prince William

County, Virginia;

JOHN F. HERRITY, individually

drrd in his official capacity as

Chairnan of the Board of

Supervisors of Fairfax

County, Virginia;

Uentne V. PENNINO, individually

and in her official capacity as

a member of the Board of

Supervisors of Fairfax

County, Virginia;

SANDRA DUCKWORTH, individually

and in her official capacity as

a member of the Board of

Supervisors of Fairfax

County, Virginia;

2

NANCY FALCK, individually

and in her official capacity

as a member of the Board of

Supervisors of Fairfax

County, Virginia;

THOMAS DAVIS, individually

and in his official capacity

aS a member of the Board of

Supervisors of Fairfax

County, Virginia;

JOSEPH ALEXANDER, individually

and in his official capacity as

a member of the Board of

Supervisors of Fairfax

County, Virginia;

AUDREY MOORE, individually

and in her official capacity

as a member of the Board of

Supervisors of Fairfax

County, Virginia;

MARIE B. TRAVESKY, individually

and in her official capacity as

a member of the Board of

Supervisors of Fairfax

County, Virginia; and

JA!{.ES !,[. SCOTT, individually

and in his official capacity

as a member of the Board of

Supervisors of Fairfax

County, Virginia;

J. HENRY Ir{cCOY, JR., individually

and in his official capacity as

Mayor of the City of Virginia

Beach, Virginia;

PATRICK L. STANDING, individually

and in his official capacity as a

nember of the City Council of the

Ci-ty of Virginia Beach, Virginia;

CLARENCE A. IIOLLAND, individually

and ln his official capacity as a

member of the City Council bf the

City of Virginia Beach, Virginia;

3-

JOEN A. BAUM, individually

and in his official capacity as a

member of the City Council of the

City of Virginia Beach, Virginia;

W. H. KIICBIN, lll, individually

and in his official capacity as a

member of the City Council of the

City of Virginia Beach, Virginia;

MEYERA OBERNDORF , individual.Iy

and in her official capacity as a

member of the City Council of the

City of Virginia Beach, Virginia;

REID ERVIN, individually

and in his official capacity as a

member of the City Council of the

City of Virginia Beach, Virginia;

REBA McCLANAN, individually

and in her official capacity as a

menber of t,he City Council of the

City of Virginia Beach, Virginia;

E. T. BUCHANAN, individually

and in his official capacity as a

member of the City Council of the

City of Virginia Beach, Virginia;

BARBARA M. HENLEY, individually

and in her official capacity as a

member of the City Council of the

City of Virginia Beach, Virginia; and

HAROLD HEISCEOBER, individually

and in his official capacity as

Vice Itlayor and a member of the

City Council of the City of

Virginia Beach, Virginia;

and

BOARD OF COUNTY SUPERVISORS

or EENRICO COUNTY, VIRGINIA,

CONSOLIDATED REPUBLICAN COMI.{ITTEE

OF. PRTNCE WII,&IAII{ COUNTY, THE CITY

OE MANASSAS, AND THE CITY OF

MANASSAS PARK;

LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OE'VIRGINIA,

Def endant- Inter venor s .

4

Amici Curiae.

civil Action No. 81-0516-R

JAIIIES H. ELAI{, JR., PATRICIA FORBES,

LILLIE MAE WILLIN,TS, LAYTON R.

FAIRCHILD, JR., BARBARA CUNNINGHAITI

II{ARY T. JONES, and LESIA ANNETTE DOBSON,

individually and on behalf

of others similarly situated t plaintiffs,

-v-

JOHN N. DAI.,TON,

Governor of Virginia;

WAYNE LUSTIG, Chairperson,

State Board of Elections;

WILLIS !I. ANDERSON,

Vice Chairperson,

State Board of Elections;

JOAN S. MAHAN, Secretdtyt

State Board of Elections,

CHARLES ROBB,

Lieutenant Governor of Virginia

and President of the Senate;

A. L. PHTLPOTT,

Speaker of the House of Delegates, Defendants.

Civil Action No. 81-0530-R

COl,ltt{ON CAUSE, a non-prof it

mernbership corporation suing

on behalf of its nembersi

J.. FRED BING}IAN;

CHARLES JANES, plainriffs,

HOWARD E. COPELAI{ID, plaintif f-Intervenor,

-v-

WAYNE LUSTIG, Chairnan,

State Board of Elections;

WILLIS M. ANDERSON,

Vice-Chairman, State

Board of Elections;

JOAN S. MAIIAN, Secretdf,y,

State Board of Elections;

JOHN N. DALTON, Governor,

State of Virginia;

J. MARSHALL COLEII{AN,

Attorney General,

State of Virginia,

Civil Action No. 81-0552-R

JACK tit. GRAVELY , AMANDA L. TEOMAS ,

THOMAS E. JARRATT, JOHN R. MASON,

LILLIE MAE POWELL, ROGER PERRY,

JUANITA PARKER, ALTON O. SNE.AD,

JAI-{ES F. GAY, MICHAEL A. BATTLE,

JOSEPHTNE E. JONES, JOSEPH E. ADAI4S,

and l,tARY SPEIGHT, individually and

on behalf of others sinilarly situated,

-v-

JOHN N. DAI.TON,

Governor of Virginia;

WAYNE LUSTIG, Member of

State Board of Elections;

WILLIS !{. ANDERSON, Member of

State Board of Elections;

JOAN S. MAHAN, Secretdty,

State Board of Elections,

Civil Action No. 81-591-A

NORBORNE P. BEVILLE, JR.,

G. RICHARD PE'ITZNER,

ODIS II{. PRICE,

CHARLES J. COLGAN 1 JE.1

-v-

Defendants.

Plaintiffs,

Defendants.

6

Plaintiffs,

JOHN N. DALTON,

Governor of Virginia;

WAYNE LUSTIG, Chairman,

State Board of Elections;

JOAN S. IVI,AHAN, SecretdTY,

State Board of Elections,

;

PAULA A. FARADAY,

ROBERT G. IIARSHALL,

CHARLES E. ORNDORTF,

ERVAN E. KUHNKE, JR.,

-V-

JOHN N. DAf,TON,

Governor of Virginia;

WAYNE LUSTIG, Chairman,

State Board of Elections;

JOAN S. MAHAN, Secretary,

State Board of Elections,

ELY, ALBERT L. , III,

-v-

WILLfS M. ANDERSON, Member,

State Board of Elections;

JOAN S. MAHAN, Secretdty,

State Board of Elections:

WA-YNE LUSTIG, Member ,

State Board of Elections;

JOHN N. DALTON,

Governor of Virginia;

J. MARSHALL COLEII{AN ,

Attorney General of Virginia;

Civil Action No. 81-0145-Roanoke

CiviL Action No. 81-0636-A

Defendants.

Plaintiffs,

Defendants.

Plainti ff ,

7

ALTON B. PRILLAMAN, Chairman,

Roanoke City Electoral Board;

DANIEL S. BROWN, Secretdty,

Roanoke City Electoral Board;

MELBA C. PIRKEY, Vice-Chairman,

August 13, 1981

Defendants.

:

Argued

BefOre BUTZNER,

States District

District Judge.

Decided

Unit,ed States Circuit

Judge, and GLEN M.

Judge, WARRINER, United

WILLIAIr,lS, United States

Robert F. Brooks (Robert W. Ackerman, Robert !1. Ro1fe, Hunton

& Willians on brief) for plaintiffs; Peter L. Trible, County

Attorney, for Board of Supervisors of Hanover County, plain-

tiff-intervenorsi Steven L. tlicas, County Attorney, for Board

of Supervisors of Chesterfield County, plaintiff-intervenorsi

David T. Stitt, County Attorney (Linda Eichelbaum Collier, As-

sistant County Attorney on brief) for Fairfax County defend-

ant-intervenorsi Anthony f. Troy (Carter G1ass, IV, Kenneth

F. Ledford, lrlays, Valentine, Davenport & lrloore, T. A. Emer-

son, Prince William County Attorney, Norborne P. Bevil1e,

Jr., Beville & Sakin, G. Richard Pf itzner, Pf itzner & t'lorley

on brief) for Virginia Beach, Prince Willian, and Manassas de-

fendant-intervenorsi William G. Broaddus, County Attorney

(Joseph P. Rapisarda, Jr. r l{ichael K. Jackson, Assistant

County Attorneys on brief) for Board of County Supervisors of

Henrico County defendant-intervenors; (Alvin J. Schilling on

brief) for amicus curiae Consolidated Republican Committee;

(Nancy A. McBride on brief) for amicus curiae League of Women

Voters of Virginia in Civil Action No. 81-0492-R; Frank R.

Parker (Stephen W. Bricker, Lawyersr Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law on brief) for plaintiffs in Civil Action No.

81-0516-R; WilLiam J. Kolasky, Jr. (Thomas Rawles Jones, Jr.i

Judith Barry Wish, Lynne E. Prymas, William D. Brighton, Fern

B. Kap1an, Wilner, Cutler & Pickering on brief) for plain-

tiffs; Eoward E. Copeland, pro s€r plaintiff intervenor in

Civil, Action No. 81-0530-R; Henry L. Marsh, IfI, S. W. Tucker

(Hill, Tucker & Marsh, Thomas I. Atkins, General Counsel,

It{ichael II. Sussman, Assistant General Counsel, NAACP Special

Contribution Fund on brief) for plaintiffs in Civil Action No.

8L-0552-R; (Norborne P. Beville, Jr., Beville & Eakin; G.

Ri-chard Pf itzner, Pfitzner & Morley on brief ) for plaintif fs

in Civil Action No. 81-591-A; (Ervan E. Kuhnke on brief) for

plaintiffs in Civil Action No. 81-0635-A; Robert R. Robrecht

for pJ.aintiff in Civil Action No. 81-0145-Roanoke; Robert H.

Patterson, Jr., Anne Marie Whittimore, James L. Sanderlin

(John S. Battler Jr., Joseph L. S. St. Amant, l,lcGuire, Woods e

Battle on brief) for defendants.

8

BUTZNER, Circuit Judge:

In these consolidated cases, several counties, organiza-

tions, and individuals challenge Virginia Acts of Assemb1y,

1981 Special Session, Chapter L2, August 11, 1981 (hereafter

referred to as the Act of August 11), which reapportioned the

electoral districts for the llouse of De1egat"".1

The defendants are a number of Virginia officials, in-

cluding those who have responsibility for conducting the

Staters elections. Various intervenors join the defendants in

supporting the entire Act or specific provisions pertaining to

their counties and cities.

The plaintiffs and their supporting intervenors attack

the Act on one or more of the following grounds:

It violates the Equa1 Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment because it does not provide for

substantial population equality in electoral dis-

tr icts;

It violates the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Anendments because it invidiously discrininates

against Virginia's black citizensi

It violates Article IV, S 4 of the United

StaEes Constitution by denying Virginians their

right to a republican form of governnent;

It violates the Equal Protection Clause of the

- Fourteenth Amendment because neither the Census

Bureau nor the General Assembly counted as residents

Challenges to the Senate redistricting plan were not

pressed before us r that plan having been rejected by the

Department of Justice on JuIy 17, 1981, during a review

required by the Voting Rights Act of 1955, 42 U.S.C.

S 1973c (1975). No new Senate redistricting plan has yet

been enacted by the General Assemb1y. No Senate elec-

tions are scheduled in 1981.

1.

q

of Norfolk, the home port of their fleet, approxi-

rnately 9r000 naval personnel deployed at sea.

It violates Article II, S 6 of the Virginia

Constitution which provides: nEvery electoral dis-

trict shall be composed of contiguous and compact

territory and shall be so congtituted as to give, qs

nearly as is practicable, representation in propor-

: tion to the population of the district.o

One or more of the plaintiffs and intervenors seek the

f olJ.owing relief :

A declaration that the Act of August 11, 1981,

is unconstitutional;

An injunction prohibiting the State Board of

Elections from conducting an election in 1981 for

members of the House of Delegates on the basis of

the August 11 Act;

An order requiring the 1981 elections to be

conducted on the basis of the 1971 apportionment

Act;

An order reapportioning the State into single-

member districts;

An injunction requiring the State to include in

the population of Norfolk approximately 9,000 naval

personnel deployed at sea.

Several parties have recommended alternative redistrict-

Because sre conclude that the Act violates the Equal Pro-

tection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and we have af-

fotded appropriate relief , ere f lnd it unnecessary to discuss

in' detail each specific conplaint.

ing plans. Several intervenors request

cific counties, leaving the remainder of

tact.

Article II, S

boundaries of its

redistricting of spe-

the August 11 Act in-

I

5 of the Virginia Constitution requires the

Senate and House of Delegates electoral

10

districts to be redrawn every ten years. The House Privileges

and Elections Comnittee had primary resPonsibility for the de-

velopment of a redistricting plan. After receipt of the 1980

census figures in February, 1981, the Committee scheduled a

sqries of public hearings on redistricting throughout the

state. Starting on March 20, the Conmittee considered at

least a dozen redlstricting p1ans, including some that Pro-

posed a more even distribution of population in each district

than the plan eventually enacted.

On april 7, 1981, the Committee reported a plan to the

Ilouse of Delegates. During the floor debate on april 8, ob-

jections were raised charging departures from the one-person,

one-vote ideal and dilut,ion of ninority voting strength.

Nonetheless, the bill was passed by the House. Following

Senate approval, the Governor signed the bill on April I0,

1gg1. 2

The Act then was submitted to the Attorney General of the

United States on April 30 for the preclearance required by S 5

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.3 On August L, the Attorney

General notified the State that the Act could not be given

clearance because some districts in Southside virginiar4

Session, ch.

1981).

2._

3.-

4.

Virginia Acts of Assembly, 1981 Special

5, codif ied at Va. Code S 24.L-L2.2 (SupP.

Codified at 42 U.S.C. S I973c (1976).

Southside includes the eastern part

Iying south of the James River.

of Virginia

11

nappear [ed] to dilute and fragment black voting strength un-

necessar iIy. "

5

The leadership of the House of Delegates and representa-

tives of various interested parties promptly held a series of

neetings with Justice Departrnent officials. Eventually, the

State and the Department reached an informal understanding of

the changes necessary for approval, and the Department agreed

to review expeditiously any new enactment of the General As-

sembly.

On August 11, the Comnittee held another public hearing

at which plans like1y to increase the black nembership of the

House of Delegates through the use of single-member districts

rrere presented. The Committee rejected these plans and ap-

proved one incorporating the changes discussed with Ehe De-

partnent of Justice. Later the same d"y, the House also re-

jected a single-member plan and adopted the Committee plan.

The Senate promptly approved the House bill and the Governor

signed it.5

The Act of August 11, 198I, was reviewed by the Depart-

ment of Justice on August L2. Late that aft,ernoon, the De-

partment notified the State that nthe Attorney General does

The Attorney General specifically mentioned

Brunswick, Greensville, Sussex, Surry, and Charles City

counties, and the cities of Petersburg and Colonial

Heights.

Virginia Acts of Assembly, 1981 Special Session, ch.

L2, August 1I, 1981, amending Va. Code S 24.L-L2.2.

5.

6.

L2

not interpose any objections to the changes [made on

August 11]." The Attorney General, however, reserved the

right to object within 60 days if new evidence cast matters in

a different light. .

: The August 11 Act provides foc 49 electoral districts em-

bracing Virginia's 95 counties and 41 incorporated cities with

an aggregate population of 5r346 1279. With a l0O-delegate

House, the ideal population for each single-member district is

therefore 53,453 citizens. The amount of deviation from the

ideal in any one district is typically neasured in percentage

terms.T The maximum statewide deviation is the sum of the

deviations of the two districts with the greatest deviations

above and below the ideal.

When the ratio of citizens to deJ.egates in two or more

adjacent districts varies greatly from the ideal, the devia-

tion can be corrected either by redrawing the district lines

or by establishing an additional "floater" district encompass-

ing the two or more underlying districts. Floater districts

The City of Richmond, for example, has four dele-

gates for its 2L9r2l4 population. Thus, Richmond has

54r804 citizens per delegate, conpared to the ideal of

53r453. The deviation is measured like this:

541804 531463 = +1341

+L34L/531453=+2.51t

Richmond--by this measure--is underrepresented by 2.51t.

When a district has fewer than 53,453 citizens, the per-

centage deviation is marked with a minus sign, and the

district is said to be overrepresented. The deviations

for each of the House districts are included in the ap-

pendix to this opinion.

7.

13

provide for one or more at-large delegates to repres_ent all of

the underlying districts.

By reducing the number of fLoater districts, the

August 11 Act virtually moots earlier disputes coDCerni:D9 the

pEoper method for calculating deviations from the ideal in

floater districts.S By the traditional House method, the

8. The Virginia General Assembly computes the devia-

tion for floaters by what it caIls the "traditional House

method.' By this nethod, one adds the population of the

underlying districts in the floater, then divides that

number by the total number of floater and non-fLoater

deJ.egates allotted to these districts. The result is

compared with the ideal ratio of citizens per delegate of

53r463r ES in the conputation illustrated in note 7,

supra.

-In

the August 11 Act, f or example, the cities of

Ilampton, Poquoson, and Williamsburg, and the counties of

James City, New Kent, and York aLl share in floater dis-

trict 47. Eampton by itself nakes up underlying district

45r the remaining areas make up underlying district 46.

District 45 has a population of L22r6L7 and two non-

floater delegates. District 46 has a population of

85r503 and one non-floater delegate. The floater dis-

trict provides one additional seat to both underlying

distr icts.

By the traditional House method, the deviation is

measured for all three districts as one:

L22r6L7 + 851603 = 208,220 total population

2081220 / 4 delegates - 521055 population per dele-

gate

52,055 53 ,463 = -1408

-1408/53,453=-2.63*

By the House method then, districts 45,46, and 47 would

have a combined deviation fron the ideal of -2.53t.

The "shared floater" method of computation works

differently. An underlying district is assumed- to be

represented by a floater delegate in proportion to that

districtrs share of the whole f loater districtrs triopula-

tion. Thus if 75t of the population of a floater

(continued)

14

August 11 Act has a maximum deviation of Zeleat, the total of

district 42 (-14.16t) and district 3 (+12.47t). By the shared

floater method, that total rises to 27.72\, the sum of the

deviations in districts 42 and 46 (14.16$ + 13.55t).

; Not counting the geographically isolated district 42, the

Eastern Shore counties, the plan has a total deviation of

22.L3* by the House nethod and 25.01t by the shared floater

8. (continued)

district live in underlying district A, district A is

said to be represented by 75t of the floater delegate.

Deviations are measured for each underlying district in-

dividually; t,he deviation f or the f loater distr ict as

such is not computed. For districts 45 and 46 then, the

deviation is computed like this:

District 45 (two non-floater delegates)

L22,6L7 population / 208,220 floater population a

.59 (share of floater delegates)

L22,6L7 / (2 + .59) E 47,342 population Per delegate

47,342 53,463 a -6L2L

-6L2L / 53,463 = -1I.45t deviation

District 45 (one non-floater delegate)

85r603 population / 208t220 floater population = .41

share of floater delegate

85,603 / (1 + .41) = 50,7L1 population per delegate

60,711 53,453 = +7248

+7248 / 53r463 = +13.56t deviation

By the shared floater nrethod, district 45 would deviate

by -11.45t and district 46 by +I3.56t from the ideal pop-

ulation per delegate. Plainly, the method of calculating

deviations in floater districts in some instances can

make a substantial difference in the result.

15

method.9 The average deviation is +4.90t, w.ith 20 districts

exceeding +5tr by the Eouse method. By the shared floater

method, the average is t5.26t, and 22 districts exceed +5t.

II

; g preliminary issue involves this courtrs authority to

decide the constitutionar controversy presented in these

cases. In McDaniel v. Sanchez, 10L S. Ct. 2224, Z23g (1981),

and connor v. waller, 42L u.s. 556 (1975), the court held that

a district court should defer consideration of an apportion-

ment pran drawn by a legislative body until after the plan has

been reviewed by the Attorney General pursuant to S 5 of the

Voting Rights Act.

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. S 1973c,

was amended in 1975 to enable expedited approval within the 60

days allowed for the Attorney Generalrs review. The Act per-

mits the Attorney General to indicate affirmatively that no

objection wiLl be made, reserving the right, nevertheless, to

reexamine the submission if additional infornation comes to

his attention before 60 days have elapsed. The Attorney Gen-

erar has irnplernented this statutory provision by adopting a

regulation to be codified as 28 C.F.R. S 51.42. See 46 Fed.

Reg. 878 (1981).

. The Attorney General's statement of August L2, 1981, that

he- "does not interpose any objections to the changes" in the

August 11 Act specifically noted that he was acting pursuant

to 28 C.F.R. S 51.42. Accordingly, he reserved the right to

By the House method, districts 3 and 48 have thegreatest variance, by the floater method, districts 43

and 46.

9.

16

reexamine the submission if additional information came to his

attention within the remainder of the 60 day period.

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act states that the pur-

pose of the procedure the Attorney General followed is !to fa-

cilitate an expedited approval within sixty days after lthe

staters] submission. . . ." Deferral of our consideration of

the constitutional questions presented by these cases until

the expiration of the remainder of the 50 day period allowed

the Attorney General would frustrate this salutary provision

of the Act. We therefore conclude that the Attorney General's

review, though subject to reexamination, lifts the restriction

that McDaniel and Connor, supra, would otherwise place on our

authority to decide these cases.

III

In Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 568 (1964), the Court

held that the trEqual Protection Clause requires that the seat,s

in both houses of a bicaneral state legislature must be appor-

tioned on a population basis." lo implement this constitu-

tional reguisite, the Court explained, a state must 'make an

honest and good faith effort to construct districts . . . as

nearly of equal population as is practicable.' 377 U.S. at

57J. This, too, is the command of Article II, S 6 of the

Vi:ginia Constitution. Recognizing that strict mathematical

equality is not imposed on state legislatures by the Constitu-

tion, the Court held that some deviations fron the ideal are

permissible if they oare based on legitimate considerations

L7

incident to the effectuation of a rational state policy

.' 377 U.S. at 579.

Virginia urges that the population deviations in the

August 11 Act are justified by the General Assembly,s consid-

eration of legitinate state interests. The state's principal

witness described the policies or guidelines considered by the

House corunittee in drafting a reapportionment plan as follows:

I think we should start with the Constitutional re-

quirement or nandate, that the district be as equal

as practicable in population.

The second guideline, and after population,

certainly I think the most important to the commit-tee, was the preservation of local subdivisions as

entities. That is, not violate the integrity of the

boundaries of the districts.

A third guideline, or a third aim of the com-

mittee within the f irst two iras to create as many

single-member districts as they could, where that

opportunity presented itself, and where the choices

were such, they would generally opt for the single-

member district.

The committee felt that they could seek to re-

tain existing legislative districtsr ES far as it

was consistent with the population standards.

The committee felt that incunbency concerns

could be taken into account. The whole area of com-

munities of interest, natural boundaries, and those

sort of factors that helped to define the district

could be considered.

The committeer ES it did its work, I believe,

applied a general rule that multi-rnember districts,

especially in the rural areas, should not be toobig. Too big is something that is hard to define,

but the committee was concerned about creating ex-

cessively large geographical districts, taking in a

Iarge number of localities in rural areas.

At one time or another, the Supreme Court has expressly

tacitly recognized that most of the policies considered byor

18

Virginia permit deviation from strict numerical equality.10

The Court has never held, however, that these state interests,

though legitimate r rn€ry be aggregated to justify population

variances as large as those disclosed by the Virginia Act.

: Indeed, dicta that we deem persuasive are to the contra-

ry. The Court dealt with Virginiafs 1971 reapportionment

statute in ttahan v. ItowelL, 410 U.S. 315 (1973). There, rec-

ognizing that Virginia had a rational interest in preserving

the integrity of political subdivisions, the Court held that a

deviation of 16.4t did not exceed constitutional limits.

Nevertheless, the Court cautioned that "this percentage may

well approach tolerable linits. . . .' 410 U.S. at 329.

Later the Court reviewed the principles that have evolved

fron its reapportionnent decisions. Referring to the upper

linits of permissible deviations, the Court said in Gaffney v.

Cummings, 412 U.S. 735, 744 (1973):

As these pronouncements have been worked out in

our cases, iE has become apparent that the larger

variations from substantial equality are too great

to be justified by any state interest so far sug-

gested. There were thus the enormous variations

struck down in the early cases beginning with

Revnolds v. Simsr BS well as the much smaller, but

nevEFEhEless nnacceptable deviations, appearing in

10. Reynolds v. Sins, 377 U.S. 533, 577 (1964) (main-

. taining equal district trrcpulations); Mahan v. Howe11,

410 U.S. 3L5, 32L-26, 328 n.9 (L973) (preserving politi-

cal subdivision and existing district boundaries); Chap-

. nan v. Meier, 42O U.S. 1, 15-15 (1975) (preferring sin-

gle- to nulti-member districts); Burns v. Richardsdn, 384

U.S. 73, 89 n.16 (1956) ("minimizing the number qf con-

tests between present incumbentsn); Swann v. Adams, 385

U.S. 440, 444 (1967) (adhering to "natural or historical

boundary lines" ) .

19

later cases such as Swann v. Adqgg, 385 U.S, 440

(1967); Kilsarlin v. E rge mrzo 11967); anlr

whitcombTE?rFis, ETiIi-u.s. L24, rGt-IG3 (1971) ."

The population variations that the Court deemed ntoo great to

be justified by any state interest so far suggestedn were

SEann v. Adams (25.65t), KilqarIin v. Hill (26.481), and

Whitcomb v. Chavis (24.78t). Virginiars deviation is compar-

able to these.

We cannot accept Virginiars argument that the Supreme

Court invalidated reapportionment plans with deviations in the

neighborhood of 25t simply because the states involved in

those cases did not articulate peculiar interests justifying

departure from practicable equality. It is true that in Swann

v. Adams, 385 U.S. 440 (L9671 , Florida presented no acceptable

reason for a deviation of 25.65t. In Kilgarlin v. HiII, 38G

U.S. 120 (19671 , where the deviation was 26.481 , Texas simi-

larly faiLed to articulate policies sufficient to justify the

variations among the populations of the legislative districts.

P1ainly the Court found it unnecessary in these cases to ad-

dress the question whether any policy courd justify such large

deviations.

In a subsequent case, however, the Court dealt with the

preservation of subdivision boundaries, the most important

policy Virginia presses. In Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S.

124 (1971), the Court referred to the following conclusion of

11. With respect to the lower end of the range of popu-

lat,ion variance, the Court has indicated that a deviation

of less than 10t is prima facie constitutional. White v.

Regester, 4L2 U.S. 755t 775 (1973) (9.9t); Gaffney v.

CunmiDgsr 412 U.S. 735, 751 (1973) (7.83t) .

20

the district court: 'It may not be possible for the Indiana

general assenbly to comply with the state constitutional re-

quirenent prohibiting crossing or dividing counties for sena-

torial apportionment, and still meet the requirements of the

Equal Protection Clause . . . .' 403 U.S. at 136. Without

rejecting the district courtrs conclusion, the Supreme Court,

nevertheless, affirmed an order requiring reapportionment.

There the deviations were 28.201 for the Senate districts and

24.781 for the House. The ratio of the largest to the smal-

lest Senate districts was L.327 to 1 and for the House, L.279

to 1. This evidence, the Court said, established a "convinc-

ing showing of malapportionnent . . . .' 403 U.S. at L62.

The deviations and ratios that the Court found unaccept-

able in Whitcgmb are comparable to those disclosed in the

Virginia reapportionment Act.

Guided by the precepts that the Supreme Court has ex-

plained in the cases we have citedr w€ conclude that the Act

of August 11 is facially unconstitutional because the devia-

tion among the populations of the districts that it creates

exceeds the limits toLerated by the Equal Protection C1ause.

Our decision does not hinge on which method is used to

calculate the deviation in the Actrs single floater district

or on whether the Eastern Shore counties should be excluded in

computing the deviation among the populations of the dis-

tricts. The deviations in the August 11 Act range from 22.L3*

to 27.72t, and the ratios of largest to smallest districts

range from L.24tL to 1.31:1, depending on the factors of the

2L

calculus. Even accepting the figures nost _favorable to the

Stater w€ believe that these variances are too J.arge. The

Suprene Court has not held a reaPPortionment statute with a

deviation of this magnitude to be constitutional.

:-

IV

Apart fron the facial unconstitutionality of the Virginia

Act, we find that the Statets announced policies do not neces-

sitate or justify the deviations among the PoPulations of the

legislative districts. This deficiency is a seParate and in-

dependent reason for holding the Act unconstitutional.

Kilgarlin v. Hill, 385 U.S. LzO, L23 (1967).-

The primary policy asserted by the state to justify the

population deviations is the preservation of the integrity of

political subdivision boundaries. Quite naturally the State

relies on l{ahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. 3I5 (1973) , which held

this policy to be a legitimate justification for a deviation

of 16.4t.

In Malfan, the Court relied on uncontradicted evidence

that it was inpossible to reduce population disparities and

stii.l maintain the integrity of county and city boundaries.

410 U.S. at 319-20 , 326. The significance of this fact was

ernphasized in Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407, 42L (1977).

There the Court rejected a district courtrs reapportionment

plan becauseT drlorg other reasonsr dn alternative plan-served

l,lississippi's policy against f ragmenting county boundar ies

and yet came closer "to achieving Cistricts that are ras

nearly of equal population as is practicable.'o 431 U.S. at

420. Distinguishing ttahan, the Connor Court said:

Under the less stringent standards governing

legislatively adopted apportionments, the goal of

maintaining political subdivisions as districts

sufficed to justify a 16.4t population deviation in- the plan for the Virginia House of Delegates. Mahan

v. Howel1, 410 U.S. 315. But in Mahan, therE-ffiE

uncfrE???icted evidence that rhe leffiture,s plan

" rproduces the minimum deviation above and below the

norm, keeping intact political boundaries.,' 431

U.S. at 420.

Here, in contrast to the situation the Court found deci-

sive in M4han, alternative plans presented to the Committee

and alternatives tendered by the litigant,s denonstrate that it

is now possibre to maintain the integrity of virginia,s polit-

ical subdivisions while substantially reducing the variations

in population among the legislative districts. we deem it be-

yond our province to press the General Assembly to adopt any

of these prans. They illustrate, however, our concLusion that

Mahan does not provide controlling precedent for the decision

of these consolidated cases.

Moreover, the 1971 Act approved in Uqhan differs signifi-

cantly from the August 11 Act. calculated by the state's

nethod, these differences may be sunmarized as follows:

197I ect Auqust 11, 1981, Act

1'.

2.--

3.

Maximum Population

Var iance

l.laximum Population

Variance (Excluding

Eastern Shore)

Average Deviation

fron Ideal Size

15.4t

16.4t

+3.89t

23

26.63r

22..L3*

+4.90t

4.

5.

a

Average Deviation

from Ideal Size

(Excluding Eastern

Shore)

Number of Districts

Exceeding 5t

Deviation

Shore )

9. Percent of

Population Able to

Elect a Majority

of Delegates

1971 Act

+3.49t

1.18 to I

49.2*

Auqust 11, 1981, Act

' 14.59t

20

L9

1.31 to 1

L.24 to I

48 .97t

15

6. Number of Districts

Exceeding 5t

Deviation (Excluding

Eastern Shore) fS

7. Ratio of Largest to

Smallest Districts 1.IB to I

8. Ratio of Largest to

Smallest Districts

(Excluding Eastern

Thus, tested by every measure, the August 1r Act departs to a

much greater degree than the 197r Act from the goal of fash-

ioning legislative districts of substantially equar popura-

tion.

The state arso announced a policy of creating singre-mem-

ber districts whenever the opportunity to do so presented it-

self. The Supreme Court has indicated on numerous occasions

that this is an appropriate consideration. rndeed, the court

has directed district courts that are obliged to draw their

owh reapportionnent plans to follow this policy in the absence

of exceptional circumstances. see chapman v. Meier , 4zo u.s.

1, 26-27 (1975).

24

Virginia appears to have given this policy a low priori-

ty, because the state departed from it frequently. Of the 31

urulti-member districts created by the Act, 10 are composed of

a single political subdivision.12 These 10 elect 30- dele-

gqtes. Thus, without transgressing the boundary of any

political subdivision, the General Assembly could have created

30 additional single-member districts. If the three-member

districts, 51 and 52, allocated to parts of Fairfax County

were also subdivided, the number of single-member districts

would increase to 35.

In view of this departure from the state's announced pol-

icy, we cannot accept the clairn that the aim of creating sin-

gIe-member districts "where that opportunity presented it-

se1f" justifies the excessive population deviations disclosed

by the Act.

The State argues that all the proposed plans that reduce

population variance while naintaining the integrity of subdi-

vision boundaries infringe the Staters other interests. This

argument may be true, but the other interests pressed by the

State cannot singly or in the aggregate justify sacrificing

population equality to the extent evidenced by the Virginia

Act.

Of the other policies considered by the legislature, the

:

record discloses that the State most assiduously pursued the

goils of retaining existing legislative districts, preserving

(2 delegat€s), 22

(2 delegatBs), 37

(2 delegat€s), 45

L2. Districts

delegates), 33

delegat€s) r 38

delegates) r and

6 (2 delegates), 2l

(4 delegates), 35

(5 delegates), 39

48 (3 delegates).

(3

(s

(2

?R

incumbents in office, and recognizing communities of, interest.

rndeed, the evidence persuades us that the state gave undue

priority to these soncerns.

Retention of existing legislative districts is u4objec-

tionable when achieved without creating significant popula-

tion variances. rt is, however, essentially a policy of

maintaining the status guo. It therefore inherently conflicts

with Virginiars Constitution and federal standards requiring

decennial reapportionment to alter the status quo by respond-

ing to shifts in the Statets population.

Preservation of incumbency interests is closely related

to retention of legislative districts and is subject to the

same limitations. It, too, ruaintains the status quo at the

expense of meeting constitutional mandates for a reapportion-

ment that reflects changes in population. The suprene court

has noted: "The fact that district boundaries may have been

drawn in a rray that minimizes the number of contests between

present incumbents does not in and of itsel,f establish invidi-

ousness.' Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73, 89 n.16

(1956).13 Thus' recognition of incumbency concerns is not in

itself unconstitutional. White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 793, 7gL

(1973). But the Court has never held that this policy

justifies large disparities in district populations.

- Virginia also relies on its policy of recognition of

coinnunities of interest as a justification for the- Act's

13. The Court made this observation in speaking of the

geographical area of districts and not with reference to

the populations of the districts.

26

population deviations. To support the allocation of dele-

gates, the staters principal witness prepared a map dividing

virginia into seven geographic regions. He then showed that

the regional allocations were substantially equar despite pop-

ulation inequalities between the several districts composing

each region.

We cannot accept this post hoc analysis as a justifica-

tion for the districtst population variances. The record

shows that the regional lines reflect only the judgment of the

witness and not that of the legislature. rt is difficult to

assume that each county on the border of a region fits pre-

cisely in the region to which it is assigned and not to a

neighboring region. Undoubtedly, the people in each large

region share a somewhat tenuous community of interest, but

their regional concerns have not been shown to eclipse either

locar or statewide concerns. l'loreover, delegates are elected

by district, not by region. The popuration of the districts,

not that of the regions, must therefore be apportioned to

achieve practicable equality.

Virginiars emphasis on community of interest also fails

to heed one of the most elementary principleS set forth in

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964). There the Court, after

recognizing that rational state policies--including the main-

te-nance of natural and historical boundaries--could warrant

soine population deviations, cautioned: "But neither h-istory

alone, nor economic or other sorts of group interests, are

permissible factors in attempting to justify disparities from

27

population-based representation. Citizensr_ not history or

economic interests, cast votes.o 377 U.S. at 579-80.

It may be that policies of retaining existing districts,

expressing concern for incumbents, and recognizing cenmuni-

ties of interest would not invalidate a plan with a deviation

slightly in excess of I0t.14 But we are not persuaded that

these policies, singly or in combinationr c6r1 justify the

deviations disclosed by the Act of August 1I.

In sum, in addition to its facial invalidity, the Act of

August 11, 1981, violates the Equal Protection Clause and the

Virginia Constitution because the Staters announced policies

either do not necessitate t ot are not adequate to justify, t,he

Actrs population variances.

v

Aligning themselves with the parties who challenge the

Act because it violates the Equa1 Protection Clause regardless

of race, several parties protest that the August 11 Act vio-

lates the rights of black citizens secured by the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments. They assail generally the Actrs

creation of numerous multi-member districts as establishing

both the purpose and effect of diluting black voting strength.

They specifically attack the composition of districts L2 and

13. 15

14.

15.

See note 11,

Changes made

earlier challenge

g.wE.

in the August 11 Act have mooted an

to districts 28 and 45.

28

In City of Mobile v. Bolden. 446 U.S. 55 (1980), the p1u-

rality opinion of the Court reviewed the linitations imposed

on the states by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments with

respect to the comPosition of legislative districts. At issue

wEs whether an at-large election of a city commission violated

the rights of black voters. with respect to the Fourteenth

Amendnent, the Court adverted to the basic principle that a

violation can be established only by showing purposeful dis-

crimination. Applying this principle, the Court said:

Despite repeated constitutionaL attacks upon

multimember legislative districts, the Court has

consistently held that they are not unconstitution-

al per se . . . We have recognized, however, that

such legislative apportionments could violate the

Fourteenth Amendment if their purpose were invidi-

ously to ninimize or cancel out the voting potential

of racial or ethnic minorities. . . . To prove such

a purpose it is not enough to show that the group

allegedly discrininated against has not elected

representatives in proportion to its numbers. . . .

A plaintiff nust prove that the disputed plan was

"conceived or operated as Ia] purposeful devic[e] to

further racial . discrimination.tr 446 U.S. at

66.

The Supreme Court has observed that criticism of multi-

member districts is based in part on "their tendency to sub-

merge minorities . . . ." Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. L24,

I59 (1971). Nevertheless, the Court has consistently held

that multi-member districts are not per se unconstitutional.

Wtritcomb, 403 U.S. at 159, 160; tlobiIe, 446 U.S. at G5. It may

well be, as the plaintiffs claim, that multi-member districts

will lirnit the number of black citizens elected to the-House

of DeJ.egates. Neither the Fourteenth nor Fifteenth Amendment,

howeverr ludrErntees a racial group the right to elect its

29

candidates in proportion to its voting potential. Eobile, 446

U.S. at 65; White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 766 (1973).

The Court has repeatedly declared that "official action

will not be held unconstitutional so1ely because it results in

a-racialIy disproportionment impact.n Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 264-65

(1977). Adverse racial effect often provides the initial step

to proving a violation of the Eourteenth Amendment, but it

must be accompanied by proof of purposeful discrinination.

Such proof is lacking when the use of multi-member districts

can be explained on grounds other than race. In the absence

of other evidence showing that black citizens are denied ac-

cess to the political process, a multi-nember reapportionment

plan is not unconstitutional. See Mobile, 446 U.S. at 70.

Here the evidence discloses that the General Assenbly in-

discrininately created many multi-member districts both in

areas containing a concentration ot, black citizens and in

those predominately composed of white residents. Multi-member

districts hrere created, the evidence reveals, to further the

announced policies of the State that we previously discussed.

Although, as we have mentioned, the State could have created

more single-member districts without crossing the boundaries

of political subdivisions, the allocation of delegates to

rnulti-member districts without regard to their racial composi-

tion negates the claim of purposeful discrimination. llore-

over, unlike the situation depicted in White v. Regester, 4L2

U.S. 755, 765-67 (1973), the evidence does not disclose that

30

black voters have less opportunity than other residents of

multi-member districts "to participate in the political proc-

esses and to elect legislators of their choice.o 412 U.S. at

766.

-- The complaints about districts L2 and 13 are best summa-

rized by guoting from the brief submitted by one of the

plaintiffs:

District 12. Old District 13, composed of

PatriEffi and Pittsylvania Counties and the

City of Martinsville, was 25.41t black (1980 Cen-

sus). This district was restructured in the 1981

plan, and Patrick and Eenry Counties and the City of

Martinsville vrere joined wit,h Floyd County, which is

only 3.32t black. This realignment dilutes black

voting strength in this area, and results in nev,

District L2, which is only 19.951 black.

aaaa

District 13. District 14 in the 1971 plan,

composed of Danville, was 29.74* black. In the 198I

plan Danville and Pittsylvania County, which also is

30t b1ack, are combined with Campbell County, which

is only 15.10t b1ack. This combination reduces the

black percentage of the Danville district from

29.74* to 25.71t.

The evidence discloses that debates in the Eouse expressly ad-

verted to the dilution of minority voting strength in both of

these districts.

Realignment of the counties, however, only mininally di-

lutes black voting strength in the districts. In neither dis-

trict was a black majority submerged by reapportionment.

Moreover, the evidence discloses that the populations of each

of the two districts deviates from the ideal by less than 21.

In'view of these factsr wB f ind no purposeful discrimi-nation

with respect to these districts that would violate the Four-

teenth Amendment.

21

The Fifteenth Amendment provides: nThe right o-f citizens

of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged

by the United States or by any State on account of race,

color, or previous condition of servitude." Reiterating prin-

ci-nIes drawn fron its apportionment cases, the Court held that

"action by a State that is racially neutral on its face vio-

lates the Fifteenth Amendment only if motivated by a discrini-

natory purpose.' uobiie, 446 u.S. at 62.

The evidence shows that black citizens have not been de-

nied the right to vote in Virginia since 1965. ContemPorary

practices and procedures do not abridge their right to regis-

ter and vote.

We therefore conclude that the August 11 Act does not

viol,ate either the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendment on the

basis of racial discrimination. See lIobile , 446 U.S. at 55,

66-7 4.

vr

Howard E. Copeland, a nember of the llouse of Delegates

from Norfolk, asserts that the General Assembly should not

have omitted approximately 9r000 Norfolk-based naval Person-

nel from Virginiars population. That figure represents the

nunber of personnel deployed overseas to the 5th or 7th fleet

on census day, April 1, 1980, and counted by the Census

Bureau as Arnericans abroad. These individuals were qot in-

cluded in any population apportionment figures provided to

Virginia. Copeland argues that the Census Bureau ought to

have required these sailors to fill out the same residency

32

forms used by nondeployed shipboard personnel. He urges that

the General Assenbly be directed to establish a Virginia

Beach-Norfolk floater district to make up for this alleged

undercount.

; Copeland offers no proof, however, of the voting resi-

dence of these 91000 citizens. Even the figure itself, based

on Navy Department records and not on an actual Census Bureau

enuneration, is suspect. Copelandrs exhibit No. I, a letter

fron the Census Bureau, notes that, based on the Bureaurs ex-

perience with nondeployed ships, nIt]he number of persons ac-

tually aboard ship can deviate considerably from Navy Depart-

ment figures . . . .' We find, in any event, that 91000 addi-

tional residents would have but slight effect on the Norfolk

and Virginia Beach populations and on the calculations of de-

viation from the ideal district populations.

Accordinglyr w€ decline to find that the General Assen-

blyrs reLiance on the 1980 census figures denied Copeland

equal protection of the laws.

VII

Having found the August 1I plan unconstitutional, vre must

consider the question of appropriate relief. Any remedy must,

of course, be considered in light of the imminence of the 1981

elections. The primary election is scheduled for September 8;

the general election for Novenber 3. The deadline for.candi-

dates to file for election has already passed. Certification

of candidates, ballot preparation, and a host of other

election mechanics must be undertaken promptly if the existing

schedule is to be folIowed.

A number of remedies have been suggested. First, the

court could inplement its own plan meeting the stringe-nt t€-

qgirements of Chaprnan v. Meier , 420 U.S. 1, 26-27 (1975), and

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407, 4L7-20 (L977'). Such a plan

might be based on one of the partiesr single-member p1ans.

Secondr w€ could perrnit the Virginia General Assembly to de-

vise a new pJ.an of its own. Third, we could direct the upcom-

ing elections to proceed under the August 11 Act as an interirn

remedy. In this eventr w€ could either allow the newly-

elected delegates to serve their usual two-year termsr 6s

urged by the state defendants, or reguire them to serve only

one year with new elections set for 1982r Ers suggested by one

of the intervenors. And fourthr w€ could order the elections

to be reorganized to follow the 197I district lines.

We find that devislng a court-ordered plan would be time-

consuming and would substantially delay the November elec-

tions. Adopting a partyrs plan would save sone tirne but would

require a drastic change in voting mechanics, also delaying

the elections. A legislatively redrawn plan would suffer from

the same drawbacks.

. The 1971 Act is substantially out of date because

Virginiars population has grown some 15t, with that growth un-

evenly spread throughout the Commonwealth. Allowing elections

to proceed under the LgTt Act would greatly disadvantage the

citizens in Virginia's rapidly growing areas and would effect

great harm to the principle of one-person, one-vote.

34

November 3 is already fixed as the date for a statewide

election for state officials including the Governor. Experi-

ence suggests that if the statewide election proceeds on

November 3 but the House of Delegates election is postponed,

vo-ter turnout for the latter will be significantly lower than

otherwise. We believe that a strong and representative turn-

out for the House election depends on holding it on

November 3.

Consequentlyr rr€ conclude that t,he August 11 Act should

be continued in effect for the November election. Interim re-

lief using an unconstitutional apportionment plan is permissi-

ble, when, as here, necessary election machinery is already in

progress for an election rapidly approaching. Reynolds v.

Sims, 317 U.S. 533, 585 (1964); see also Kilgarlin v. HiIl,

385 U.S. L20, LzL 11967); Toombs v. Fortson, 24L E. Supp. 65,

71 (N.D. Ga. 1965) , af f 'd per curiam, 384 U.S. 210 (1955) .

Whenever possible, of course, a state legislature should

have an opportunity to redraw a plan found by the courts to be

unconstitutional. Reynolds V. Sims, 377 U.S. at 586-87; Wise

v. Lipscomb, 437 U. S. 535 , 539-40 (1978 ) . Although $re have

found that it would be impractical for the General Assembly to

devise a plan that would accommodate an election on

November 3, ire believe that that body can constitutionally re-

i

apportion the State in the period of five months ending

February 1, 1982.15 If this is not doner w€ will be compelled

fn accordance with directives of the Supreme Court,

we refrain from giving specific guidelines or constraints

for the legislaturers redrafting. See Wise v. Lipscomb,

437 U.S. 535, 540 (1978); Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S.

73 , 83-85 , 89 (1966 ) .

15.

35

to consider drafting a court plan. We retain jurisdiction for

this purpose. The State nust forthwith submit any new Act to

the Attorney General pursuant to the Voting Rights Act of

1965. E McDaniel v. Sanchez, 101 S. Ct. 2224, 2238 n.35

(1981). We have selected the deadline of February I, L982,

because the history of this case shows that a later date will

interfere with the Staters general election schedule.

Because Virginiars citizens are entitled to vote as soon

as possible for their representatives under a constitutional

apportionment planr w€ will limit the terms of members of the

House of Delegates elected in 198L to one year. We also will

direct the state eLection officials to conduct a new election

in L982 for the House of Delegates under the General

Assemblyrs new Act or our own pIan. That election should be

held the same day as the November general election. See Va.

Code S 24.1-1(5)(a). Delegates elected then shall serve for

the remainder of the 1982-84 term unless the General Assembly

chooses to extend the term to a fuII two years.

VII I

At least six of the parties involved in this case have

requested that the court grant thern reasonable attorneyrs fees

incurred in this litigation pursuant to 42 U.S.C. SS 1973 1(e)

and 1988.

I Ordinarily, all claims for relief, including a party's

request for attorneyrs fees, must be decided by the district

35

court before a judgment becomes finar and ripe for appeal.

Liberty t'tutual Insurance , Co. v. Wetzel , 424 U. S. 737 , 7 42

(1975). rnterlocutory injunctions, however, present an excep-

tion to this rule because they are imrnediatery appealable. 2g

u-s.c. s 1253

rn this case the propriety of attorneyrs fees has not yet

been briefed nor have any affidavits or other supporting evi-

dence been submitted to this court to justify any award.

Therefore, given the proximity of the upcoming elections and

the importance of alrowing any aggrieved party an opportunity

for immediate appeal of t,he other issues in this caser w€ will

not defer the entry of our interlocutory order to address the

question of attorneyrs fees but will reserve consideration of

this question for a later tine.

37

ACTS OF

lSggIgtr

1981 HOUSE OF DELEGATES DISTRICTS

ASSEIIBLY, 1981 SPECTAI SESSION, CHAPTER

(August 11, 1981)

DTSTRTCT

L2

DELEGATES POPUI,ATION

Ig, g05

25 ,956

4,757

25, 05 g

43,853

119,450

DEVIATION

I. Dickenson

Lee

Norton

Scott

Wise

+11.71t

2. Bristol

Smyth

Washington

L9 ,042

33,365

46 ,487

2 __ gg,gg5 -7.51r

3. Buchanan

Russell

Tazewell

37,989

31, 751

50,511

L20 ,26L +L2 .472

4.. Bland

Grayson

Wythe

Galax

6 ,349

L6,579

25 ,522

6 ,524

34 9?4 +2.831

Carroll

Giles

Montgomery

Pulaski

Radford

27,270

17, 910

53,516

35 ,229

L3 ,225

-.--

L57 050 -2.088

5. Roanoke City L00 ,427

100 427 -6.08s

7 . Crai.g

Roanoke County

Salem

3,948

72,945

23 ,958

100,85r -5 . 6 8r

DELEGATES DISTRICT

8. Alleghany

Botetourt

Clifton Forge

Covi.ngton

POPULATIO}I

14,333

23 ,27 0

5 ,046

9,053

DEVIATION

-3.24t1 ; 5l ,712

9. Bedford Cor:nty

Franklin County

Rockbridge

Buena Vista

Lexington

tseCford City

34 ,927

35 ,7 10

17, 911

6 ,7L7

7,292

5,991

108,5782 +1.54t

10. Augusta

Bath

Highland

Staunton

lfaynesboro

53,732

5,460

2 ,937

?L,957

L5 ,329

gg,7L5 -5 .7 4*

11. ,l:nherst

Nelson

Lynchburg

29 ,122

L2 ,204

66 ,7 43

108,069 +1. C7B

L2. PJ-oyC

Henry

MartinsvilLe

Patrick

11,553

57,654

18,14 9

17,5E5

I04,951 -I.85ts

13. Campbell

Pittsylvania

Danville

45 ,424

66 , L47

45 ,642

r57 2t3 -1 .98r

14. Charlotte

Halifax

South Boston

12,266

30,418

7,093

49,777 -5.89r

a

DELEGATES DISTRTCTS

15. Greene

Rockingham

Shenandoah

Harrisonburg

POPULArION DEVIATION

7,525

57, 038

27,559

19,671

111,893 +4 .551

16. Frederick

Winchester

34,150

20 ,2L7

34 ,367 +1.69t

L7. Loudoun 57,427

57 ,4271 +7 .4Lt

18. Clarke 9,955

Page 19,40i

Rappahannock 5,093

Warren 21,200

1 56 ,659 +5.98t

19. Culpeper

Fauquier_.

22 ,520

35,899

58,509 +9 .44*

20. Stafford

Predericksburg

40 ,470

L5,322

55,792 +4.35t

2L. Alexandria 103,217

L03 ,217 -3.47*

22. Arlington 152,599

152,599 -4.85t

23. l'lanassas

Manassas Park

Prince william

15,439

6 '524144,703

155,555 +3.9It

DELEGATES DTSTRICT

24. Albemarle

Fluvanna

Charlottesville

POPULATION

50,589

10,244

45,010

105,943

DEVIATION

-0.92*2

25. Amelia

Appomattox

Buckingham

Cumberland

Prince Edward

8,405

11,971

11, 751

7,991

15,455

56 ,464 +5.51t1

26. Nottorvay

Lr.rnenburg

Mecklenburg

14 ,666

12,L24

29,444

56,234 +5.18t

27. Brunswick

Dinwiddie

Greensville

Empori a

Sussex

Petersburg

15 ,532

22 ,502

10,903

1 ,840

lo ,87 4

41, 055

10s | 9_q5 -0 . 9s*

29. Goochland

Louisa

Madison

Orange

11, 751

L7,825

L0,232

!7,827

57 ,645 +7.82*

I

30. Caroline

Spotsylvania

L7,904

34 ,435

52 ,339 -2. I0r

32. llenrico

Hanover

180,735

50, 3g g

-4-

231, 133 +8.08*

DELEGATES

4

DISTRICT

33. Richmond City

POPULATION

2L9,2L4

219 ,2L4

DEVIATION

+2. 51t

34. Chesterfield

Powhatan

ColoniaI Heights

LA]- ,372

13,062

15,509

I70,943 +6 .588

35. Prince George

Charles CitY

Hopewell

25,733

6 ,592

23 ,397

55 ,822 +4.418

35. Chesapeake L14,226

114,226 +5.83t

37. NorfoLk 266 ,979

266,979 -0.13r

38. Virginia Beach 252,199

262,L99 -1. 91?

39. Portsmouth L04 ,571

L04 ,577 -2.20*

41. Suffolk

Franklin CitY

Isle of wight

Southampton

Surry

47,621

7,308

2L ,603

18,731

5,046

101,309 -5.25t

42. Accomack

Northampton

31,25 g

L4 ,625

-5-

45,893 -14.15r

.lrr'

DELEGATES DISTRTC"

43. King George

Lancaster

Northcurnberland

Richmond County

WestmoreLand

POPULATTON

10,543

10,129

9 ,828

5,952

14 , oAL

DEVIATION

-3.58t

;

1 51,493

44. Essex

Gloucester

King and Queen

King William

Mathews

l,liddlesex

9,954

20 , L07

5,959

9 ,327

7,995

7 ,7Lg

59,980I +12. I9t

45. Hampton

46. James City

New Kent

York

Poquoson

williamsburg

47. Floater 45 and 45

122 ,617

22,763

8,781

35,453

8,726

9,870

85,503

208 ,220

-2 .63*

48. Newport News 144

144

,903

903 -9.66r

49. Fairfax

Pal1s'Church

14 7, 310

9,515

L56 ,825 -2.222

50. Fairfax

Fairfax City

137,783

19, 390

3 157,!73 -2.01r

155

155

,20451. Fairfax

204 -3.238

. DELEGATES DISTRICT POPULATION DEVIATION

155,504

r55,604 -2.35r

52 - Pairfax