Draft Order; Ruling on Issue of Segregation

Working File

September 27, 1971

31 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Draft Order; Ruling on Issue of Segregation, 1971. 0ee08e9e-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/868d34fb-0a42-4926-807b-1a1e49af1fca/draft-order-ruling-on-issue-of-segregation. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

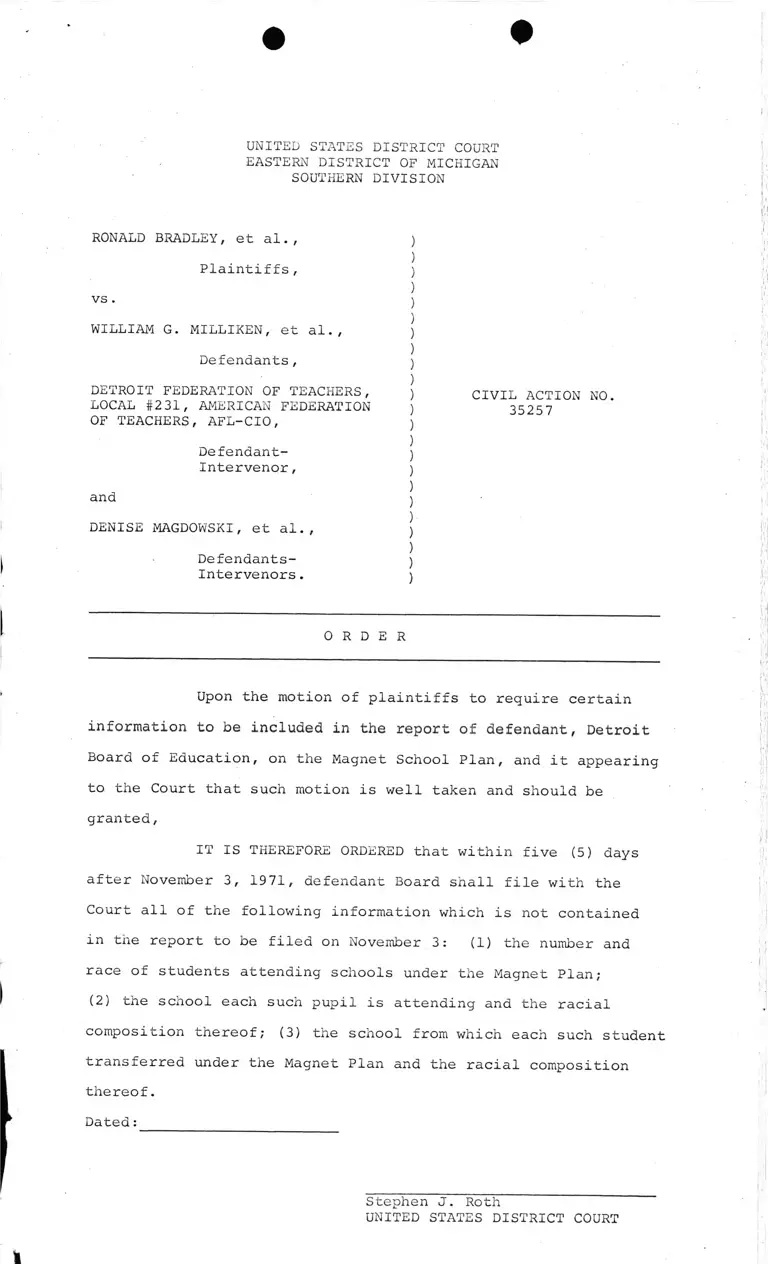

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs .

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants,

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-

Intervenor,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al. ,

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)Defendants- )

Intervenors. \

CIVIL ACTION NO.

35257

O R D E R

Upon the motion of plaintiffs to require certain

information to be included in the report of defendant, Detroit

Board of Education, on the Magnet School Plan, and it appearing

to the Court that such motion is well taken and should be

granted,

IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED that within five (5) days

after November 3, 1971, defendant Board shall file with the

Court all of the following information which is not contained

in the report to be filed on November 3: (1) the number and

race of students attending schools under the Magnet Plan;

(2) the school each such pupil is attending and the racial

composition thereof; (3) the school from which each such student

transferred under the Magnet Plan and the racial composition

thereof.

Dated:

Stephen J. Roth

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

P H O N E ( 9 0 1 ) S 2 5 - 0 6 O IRATNER, SUGARMON & LUCAS

A T T O R N E Y S A T L A W

S U I T E 5 2 5

C O M M E R C E T I T L E B U I L D I N G

M A R V I N L. R A T N E R

R . B . S U G A R M O N , J R .

L O U I S R. L U C A S

W A L T E R L. B A I L E Y , J R .

I R V I N M. S A L K Y

M I C H A E L B. K A Y

W I L L I A M E. C A L D W E L L

MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE 38103

October 25, 1971

B E N L. H O O K S

OF COUNSEL

George E. Bushnell, Jr., Esq.

2500 Detroit Bank and Trust Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

RE: Bradley v. Milliken

NO. 35-257

Dear Mr. Bushnell:

The deadline for filing the report and evaluation of

the Magnet Plan is coming up soon, and as plaintiffs will

have only ten days to respond to such report and evaluation,

we wish to request that certain information be included in

the report. Past reports on the Magnet Plan have shown

the number of pupils who have chosen schools under the Magnet

and the race of the pupils involved, but the reports

have not shown the schools from which the pupils transferred.

We, therefore, request that the report to be filed pursuant

to the court1s last order include with regard to pupils

selecting schools under the Magnet Plan the school from which

each pupil transferred, as well as the race of said pupil.

LRL:pw

cc: Honorable Stephen J. Roth, Judge

Theodore Sachs, Esq.Eugene Krasicky, Esq.

Alexander B. Ritchie, Esq.

Norman J. Chachkin, Esq.\^

Paul Diamond, Esq.

E. Winthrop McCroom, Esq.

Very truly yours

•>

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs A 1 h’ U t C O P Y

V.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

FREDERICK W. JOHN^pN, Clerk

BY ..--i— i- • ^

Y CLERK

Defendants

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-

Intervenor

CIVIL ACTION NO:

35257

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Def endants-

Intervenor

RULING ON ISSUE OF SEGREGATION

This action was corrunenced August 18, 1970, by

plaintiffs, the Detroit Branch of the National Association for

*the Advancement of Colored People and individual parents ana

students, on behalf of a class later defined by order of the

Court dated February 15, 1971, to include "all school children

of the City of Detroit and all Detroit resident parents who

have children of school age." Defendants are the Board of

Education of the City of Detroit, its members and its former

suoerintendent of schools, Dr. Norman A. Drachler, the Governor,

Attorney General, State Board of Education and State Superin

tendent of Public Instruction of the State of Michigan. In

their complaint, plaintiffs attacked a statute of the State

of Michigan known as Act 48 of the 1970 Legislature on the

The standing of the NAACP as a proper party plaintiff was

not contested by the original defendants and the Court expresse.1

no opinion on the matter.

ground that it put the State of Michigan in the position of

unconstitutionally interfering with the execution and operation

of a voluntary plan of partial high school desegregation

(known as the April 7, 1970 Plan) which had been adopted by

the Detroit Board of Education to be effective beginning with

the fall 1970 semester. Plaintiffs also alleged that the

Detroit Public School System was and is segregated on the

basis of race as a result of the official policies and actions

of the defendants and their predecessors in office.

Additional parties have intervened in the litigation

since it was commenced. The Detroit Federation of Teachers

(DFT) which represents a majority of Detroit Public school

teachers in collective bargaining negotiations with the defendant

Board of Education, has intervened as a defendant, and a group

of parents has intervened as defendants.

Initially the matter was tried on plaintiffs' motion

for preliminary injunction to restrain the enforcement of

Act 48 so as to permit the April 7 Plan to be implemented. On

that issue, this Court ruled that plaintiffs were not entitled

to a preliminary injunction since there had been no proof that

Detroit has a segregated school system. The Court of Appeals

found that the "implementation of the April 7 Plan was thwarted

by State action in the form of the Act of the Legislature of

Michigan," (433 F.2d 897, 902), and that such action could not

be interposed to delay, obstruct or nullify steps lawfully

taken for the purpose of protecting rights guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment.

The plaintiffs then sought to have this Court direct

the defendant Detroit Board to implement the April 7 Plan by

the start of the second semester (February, 1971) in order to

remedy the deprivation of constitutional rights wrought by the

unconstitutional statute. In response to an order of the Court,

defendant Board suggested two other plans, along with the

April 7 Plan, and noted priorities, with top priority assigned

to the so-called "Magnet Plan." The Court acceded to the

wishes of the Board and approved the Magnet Plan. Again,

plaintiffs appealed but the appellate court refused to pass

on the merits of the plan. Instead, the case was remanded

with instructions to proceed immediately to a trial on the

merits of plaintiffs' substantive allegations about the Detroit

School System. 438 F .2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971).

Trial, limited to the issue of segregation, began

April 6, 1971 and concluded on July 22, 1971, consuming 41

trial days, interspersed by several brief recesses necessitated

by other demands upon the time of Court and counsel. Plaintiffs

introduced substantial evidence in support of their contentions,

including expert and factual testimony, demonstrative exhibits

and school board documents. At the close of plaintiffs' case,

in chief, the Court ruled that they had presented a prima facie

case of state imposed segregation in the Detroit Public Schools;

accordingly, the Court enjoined (with certain exceptions) all

further school construction in Detroit pending the outcome

of the litigation.

The State defendants urged motions to dismiss as to

them. These were denied by the Court.

At the close of proofs intervening parent defendants

(Denise Magdowski, et al.) filed a motion to join, as parties 85

«contiguous "suburban" school districts - all within the so-

"... .......' ' " ■ • ■ 1 " V - ' - ' U1 “ - - • • - -■ ■ ~ ~ - - P Y- ; .V. . .. 1- " " P .

called Larger Detroit Metropolitan area. This motion was

taken under advisement pending the determination of the issue

of segregation.

It should be noted that, in accordance with earlier

rulings of the Court, proofs submitted at previous hearings

in the cause, were to be and are considered as part of the

proofs of the hearing on the merits.

In considering the present racial complexion of the

City of Detroit and its public school system we must first look

to the past and view in perspective what has happened in the

last half century. In 1920 Detroit was a predominantly white

city - 91% - and its population younger than in more recent

times. By the year 1960 the largest segment of the city's

white population was in the age range of 35 to 50 years, while

its black population was younc • o r * ro vj-i. l. XiiHi i v - j C iv- j c ; • i u c

population of 0-15 years of age constituted 30% of the total

population of which 60% were white and 40% were black. In

1970 the white population was principally aging— 45 years—

while the black population was younger and of childbearing age.

Childbearing blacks equaled or exceeded the total white

population. As older white families without children of

school age leave the city they are replaced by younger black

families with school age children, resulting in a doubling

of enrollment in the local neighborhood school and a complete

change in student population from white to black. As black

inner city residents move out of the core city they "leap-frog"

the residential areas nearest their former homes and move to

areas recently occupied by whites.

The population of the City of Detroit reached its

-4-

-

highest point in 1950 and has been declining by approximately

169,500 per decade since then. In 1950, the city population

constituted 61% of the total population of the standard

metropolitan area and in 1970 it was but 36% of the metro

politan area population. The suburban population has

increased by 1,978,000 since 1940. There has been a steady

out-migration of the Detroit population since 1940. Detroit

today is principally a conglomerate of poor black and white

plus the aged. Of the aged, 80% are white.

If the population trends evidenced in the federal

decennial census for the years 1940 through 1970 continue,

the total black population in the City of Detroit in 1980

will be approximately 840,000, or 53.6% of the total. The

total population of the city in 1970 is 1,511,000 and, if

past trends continue, will be 1,338,000 in 1980. In school

year 1960-61, there were 285,512 students in the Detroit

Public Schools of which 130,765 were black. In school year

1966-67, there were 297,035 students, of which 168,299 were

black. In school year 1970-71 there were 289,743 students of

which 184,194 were black. The percentage of black students

in the Detroit Public Schools in 1975-76 will be 72.0%,

in 1980-81 will be 80.7% and in 1992 it will be virtually

100% if the present trends continue. In 1960, the non-white

population, ages 0 years to 19 years, was as follows:

0 - 4 years 4 2%

5 - 9 years 36%

10 - 14 years 28%

15 - 19 years 18%

5-

iSAv?.'- • • its. iT . •... z

In 1970 the non-white population, ages 0 years to 19 years,

was as follows:

0 - 4 years 48%

5 - 9 years 50%

10 - 14 years 50%

15 - 19 years 40%

The black population as a percentage of the total population

in the City of Detroit was:

(a) 1900 1.4%

(b) 1910 1.2%

(c) 1920 4.1%

(d) 1930 7.7%

(e) 1940 9.2%

(f) 1950 16.2%

(g) 1960 28.9%

(h) 1970 43.9%

The black population as a percentage of total student

population of the Detroit Public Schools was as follows:

(a) 1961 45.8%

(b) 1963 51.3%

(c) 1964 53.0%

(d) 1965 54.8%

(e) 1966 56.7%

(f) 1967 58.2%

(g) 1968 59.4%

(h) 1969 61.5%

(i) 197 0 63.8%

-6-

S' 'T* * * 4SRT ~+r ■*

For the years indicated the housing characteristics in the

City of Detroit were as follows:

(a) 1960 total supply of housing

units was 553,000

(b) 1970 total supply of housing

units was 530,770

The percentage decline in the white students in the

Detroit Public Schools during the period 1961-1970 (53.6%

in 1960; 34.8% in 1970) has been greater than the percentage

decline in the white population in the City of Detroit during

the same period (70.8% in 1960; 55.21% in 1970), and

correlatively, the percentage increase in black students in

the Detroit Public Schools during the nine-year period 1961-

1970 (45.8% in 1961; 63.8% in 1970) has been greater than the

percentage increase in the black population of the City of

Detroit during the ten-year period 196G-IS7G (28.3% in.

1960; 43.9% in 1970). In 1961 there were eight schools in

the system without white pupils and 73 schools with no

Negro pupils. In 1970 there were 30 schools with no

white pupils and 11 schools with no Negro pupils, an

increase in the number of schools without white pupils of

22 and a decrease in the number of schools without

Negro pupils of 62 in this ten-year period. Between

1968 and 1970 Detroit experienced the largest increase in

percentage of black students in the student population of any

major northern school district. The percentage increase in

Detroit was 4.7% as contrasted with —

New York 2.0%

Los Angeles 1.5%

Chicago 1.9%

-7-

Philadelphia 1.7%

Cleveland 1.7%

Milwaukee 2.6%

St. Louis 2.6%

Columbus 1.4%

Indianapolis 2.6%

Denver 1.1%

Boston 3.2%

San Francisco 1.5%

Seattle 2.4%

In 1960, there were 266 schools in the Detroit

School System. In 1970, there were 319 schools in the

Detroit School System.

In the Western, Northwestern, Northern, Murray,

Northeastern, Kettering, King and Southeastern high school

service areas, the following conditions exist at a level

significantly higher than the city average:

(a) Poverty in children

(b) Family income below poverty level

(c) Rate of homicides per population

(d) Number of households headed by females

(e) Infant mortality rate

(f) Surviving infants with neurological

defects

(g) Tuberculosis cases per 1,000 population

(h) High pupil turnover in schools

The City of Detroit is a community generally divided

by racial lines. Residential segregation within the city and

throughout the larger metropolitan area is substantial, per

vasive and of long standing. Black citizens are located in

-8-

separate and distinct areas within the city and are not

generally to be found in the suburbs. While the racially

unrestricted choice of black persons and economic factors

may have played some part in the development of this pattern

of residential segregation, it is, in the main, the result

of past and present practices and customs of racial discrimina

tion, both public and private, which have and do restrict the

housing opportunities of black people. On the record there

can be no other finding.

Governmental actions and inaction at all levels,

federal, state and local, have combined, with those of

private organizations, such as loaning institutions and real

estate associations and brokerage firms, to establish and

to maintain the pattern of residential segregation throughout

the Detroit metropolitan area. It is no answer to say that

restricted practices grew gradually (as the black population

in the area increased between 1920 and 1970), or that since

1948 racial restrictions on the ownership of real property

have been removed. The policies pursued by both government

and private persons and agencies have a continuing and present

effect upon the complexion of the community - as we know,

the choice of a residence is a relatively infrequent affair.

For many years FHA and VA openly advised and advocated the

maintenance of "harmonious" neighborhoods, î .e., racially

and economically harmonious. The conditions created

continue. While it would be unfair to charge the present

defendants with what other governmental officers or agencies

have done, it can be said that the actions or the failure to

act by the responsible school authorities, both city and

state, were linked to that of these other governmental units.

-9-

When we speak of governmental action we should not view the

different agencies as a collection of unrelated units.

Perhaps the most that can be said is that all of them,

including the school authorities, are, in part, responsible

for the segregated condition which exists. And we note that

just as there is an interaction between residential patterns

and the racial composition of the schools, so there is a

corresponding effect on the residential pattern by the racial

composition of the schools.

Turning now to the specific and pertinent (for our

purposes) history of the Detroit school system so far as it

involves both the local school authorities and the state

school authorities, we find the following:

During the decade beginning in 1950 the Board

created and maintained optional attendance zones in neighbor

hoods undergoing racial transition and between high school

attendance areas of opposite predominant racial compositions.

In 1959 there were eight basic optional attendance areas

affecting 21 schools. Optional attendance areas provided

pupils living within certain elementary areas a choice of

attendance at one of two high schools. In addition there

was at least one optional area either created or existing in

1960 between two junior high schools of opposite predominant

racial components. All of the high school optional areas,

except two, were in neighborhoods undergoing racial

transition (from white to black) during the 1950s. The two

exceptions were: (1) the option between Southwestern

(61.6% black in 1960) and Western (15.3% black); (2) the

option between Denby (0% black) and Southeastern (30.9% black).

With the exception of the Denby-Southeastern option (just

. ' f t r s s w w w t m - y & y . y & - ™ iiiiiiTiT‘rriiiiir iTm^in T T r" ~~^7''"":~ ■

noted) all of the options were between high schools of

opposite predominant racial compositions. The Southwestern-

Western and Denby-Southeastern optional areas are all white

on the 1950, 1960 and 1970 census maps. Both Southwestern

and Southeastern, however, had substantial white pupil

populations, and the option allowed whites to escape integra

tion. The natural, probable, forseeable and actual effect of

these optional zones was to allow white youngsters to escape

identifiably "black" schools. There had also been an optional

zone (eliminated between 1956 and 1959) created in "an

attempt . . . to separate Jews and Gentiles within the

system," the effect of which was that Jewish youngsters

went to Mumford High School and Gentile youngsters went to

Cooley. Although many of these optional areas had served

their purpose by 1960 due to the fact that most of the areas

had become predominantly “black, one optional area (Southwestern-

Western affecting Wilson Junior High graduates) continued until

the present school year (and will continue to effect 11th and

12th grade white youngsters who elected to escape from

predominantly black Southwestern to predominantly white Western

High School). Mr. Henrickson, the Board's general fact witness,

who was employed in 1959 to, inter alia, eliminate optional

areas, noted in 1967 that: "In operation Western appears to

be still the school to which white students escape from

predominantly Negro surrounding schools." The effect of

eliminating this optional area (which affected only 10th

graders for the 1970-71 school year) was to decrease

Southwestern from 86.7% black in 1969 to 74.3% black in 1970.

The Board, in the operation of its transportation

to relieve overcrowding policy, has admittedly bused black

-11-

• •

pupils past or away from closer white schools with available

space to black schools. This practice has continued in

several instances in recent years despite the Board's avowed

policy, adopted in 1967, to utilize transportation to

increase integration.

With one exception (necessitated by the burning of

a white school), defendant Board has never bused white

children to predominantly black schools. The Board has not

bused white pupils to black schools despite the enormous

amount of space available in inner-city schools. There were

22,961 vacant seats in schools 90% or more black.

The Board has created and altered attendance zones,

maintained and altered grade structures and created and

altered feeder school patterns in a manner which has had the

natural, probcible and actual effect of continuing black and

white pupils in racially segregated schools. The Board admits

at least one instance where it purposefully and intentionally

built and maintained a school and its attendance zone to

contain black students. Throughout the last decade (and

presently) school attendance zones of opposite racial

compositions have been separated by north-south boundary lines,

despite the Board's awareness (since at least 1962) that

drawing boundary lines in an east-west direction would result

in significant integration. The natural and actual effect of

these acts and failures to act has been the creation and

perpetuation of school segregation. There has never been a

feeder pattern or zoning change which placed a predominantly

white residential area into a predominantly black school zone

or feeder pattern. Every school which was 90% or more black

in 1960, and which is still in use today, remains 90% or more

-12-

#

black. Whereas 65.8% of Detroit's black students attended

90% or more black schools in I960, 74.9% of the black students

attended 90% or more black schools during the 1970-71 school

year.

The public schools operated by defendant Board are

thus segregated on a racial basis. This racial segregation

is in part the result of the discriminatory acts and omissions

of defendant Board.

In 1966 the defendant State Board of Education and

Michigan Civil Rights Commission issued a Joint Policy State

ment on Equality of Educational Opportunity, requiring that

"Local school boards must consider the factor of

racial balance along with other educational

considerations in making decisions about selection

of new school sites, expansion of present

facilities . . . . Each of these situations

presents an opportunity for integration."

Defendant State Board's "School Plant Planning Handbook" requires

that

"Care in site location must be taken if a serious

transportation problem exists or if housing

patterns in an area would result in a school

largely segregated on racial, ethnic, or socio

economic lines."

The defendant City Board has paid little heed to these statements

and guidelines. The State defendants have similarly failed to

take any action to effectuate these policies. Exhibit NN

reflects construction (new or additional) at 14 schools which

opened for use in 1970—71; of these 14 schools, 11 opened over

90% black and one opened less than 10% black. School con

struction costing $9,222,000 is opening at Northwestern High

School which is 99.9% black, and new construction opens at

Brooks Junior High, which is 1.5% black, at a cost of $2,500,000.

13

The construction at Brooks Junior High plays a dual segregatory

role: not only is the construction segregated, it will result

in a feeder pattern change which will remove the last majority

white school from the already almost all-black Mackenzie High

School attendance area.

Since 1959 the Board has constructed at least 13

small primary schools with capacities of from 300 to 400 pupils.

This practice negates opportunities to integrate, "contains"

the black population and perpetuates and compounds school

segregation.

The State and its agencies, in addition to their

general responsibility for and supervision of public education,

have acted directly to control and maintain the pattern of

segregation in the Detroit schools. The State refused, until

this session of the legislature, to provide authorization or

funds for the transportation of pupils within Detroit regardless

of their poverty or distance from the school to which they

were assigned, while providing in many neighboring, mostly

white, suburban districts the full range of state supported

transportation. This and other financial limitations, such

as those on bonding and the working of the state aid formula

whereby suburban districts were able to make far larger per

pupil expenditures despite less tax effort, have created and

perpetuated systematic educational inequalities.

The State, exercising what Michigan courts have held

to be is "plenary power" which includes power "to use a

statutory scheme, to create, alter, reorganize or even dissolve

a school district, despite any desire of the school district,

«its board, or the inhabitants thereof," acted to reorganize

-14-

• •

the school district of the City of Detroit.

The State acted through Act 48 to impede, delay

and minimize racial integration in Detroit schools. The

first sentence of Sec. 12 of the Act was directly related to

the April 7, 1970 desegregation plan. The remainder of the

section sought to prescribe for each school in the eight

districts criterion of "free choice" (open enrollment) and

"neighborhood schools" ("nearest school priority acceptance"),

which had as their purpose and effect the maintenance of

segregation.

In view of our findings of fact already noted we

think it unnecessary to parse in detail the activities of the

local board and the state authorities in the area of school

construction and the furnishing of school facilities. It is

our conclusion that these activities were in keeping, generally,

with the discriminatory practices which advanced or perpetuated

racial segregation in these schools.

It would be unfair for us not to recognize the

many fine steps the Board has taken to advance the cause of

quality education for all in terms of racial integration and

human relations. The most obvious of these is in the field

of faculty integration.

Plaintiffs urge the Court to consider allegedly

discriminatory practices of the Board with respect to the

hiring, assignment and transfer of teachers and school

administrators during a period reaching back more than 15

years. The short answer to that must be that black teachers

and school administrative personnel were not readily available

in that period. The Board and the intervening defendant union

-15-

have followed a most advanced and exemplary course in adopting

and carrying out what is called the "balanced staff concept" -

which seeks to balance faculties in each school with respect

to race, sex and experience, with primary emphasis on race.

More particularly, we find:

1. With the exception of affirmative policies

designed to achieve racial balance in instructional staff, no

teacher in the Detroit Public Schools is hired, promoted or

assigned to any school by reason of his race.

2. In 1956, the Detroit Board of Education adopted

the rules and regulations of the Fair Employment Practices

Act as its hiring and promotion policy and has adhered to

this policy to date.

3. The Board has actively and affirmatively sought

out and hired minority employees, particularly teachers and

administrators, during the past decade.

4. Between 1960 and 1970, the Detroit Board of

Education has increased black representation among its

teachers from 23.3% to 42.1%, and among its administrators

from 4.5% to 37.8%.

5. Detroit has a higher proportion of black

administrators than any other city in the country.

6. Detroit ranked second to Cleveland in 1968

among the 20 largest northern city school districts in the

percentage of blacks among the teaching faculty and in 1970

surpassed Cleveland by several percentage points.

-16-

7. The Detroit Board of Education currently

employs black teachers in a greater percentage than the

percentage of adult black persons in the City of Detroit.

8. Since 1967, more blacks than whites have been

placed in high administrative posts with the Detroit Board

of Education.

9. The allegation that the Board assigns black

teachers to black schools is not supported by the record.

10. Teacher transfers are not granted in the Detroit

Public Schools unless they conform with the balanced staff

concept.

11. Between 1960 and 1970, the Detroit Board of

Education reduced the percentage of schools without black

faculty from 36.3% to 1.2%, and of the four schools currently

without black faculty, three are specialized trade schools

where minority faculty cannot easily be secured.

12. In 1968, of the 20 largest northern city

school districts, Detroit ranked fourth in the percentage

of schools having one or more black teachers and third in

the percentage of schools having three or more black teachers.

13. In 1970, the Board held open 240 positions in

schools with less than 25% black, rejecting white applicants

for these positions until qualified black applicants could

be found and assigned.

14. In recent years, the Board has come under pressure

from large segments of the black community to assign male

black administrators to predominantly black schools to serve

-17

as male role models for students, but such assignments have

been made only where consistent with the balanced staff

concept.

15. The numbers and percentages of black teachers

in Detroit increased from 2,275 and 21.6%, respectively,

in February, 1961, to 5,106 and 41.6%, respectively, in

October, 1970.

16. The number of schools by percent black of

staffs changed from October, 1963 to October, 1970 as

follows:

Number of schools without black teachers—

decreased from 41, to 4.

Number of schools with more than 0%, but less

than 10% black teachers— decreased from 58, to 8.

Total number of schools with less than 10% black

teachers— decreased from 99, to 12.

Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers—

increased from 72, to 124.

17. The number of schools by percent black of staffs

changed from October, 1969 to October, 1970, as follows:

Number of schools without black teachers— decreased

from 6, to 4.

Number of schools with more than 0%, but less than

10% black teachers— decreased from 41, to 8.

Total number of schools with less than 10% black

teachers— decreased from 47, to 12.

Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers—

increased from 120, to 124.

18. The total number of transfers necessary to

achieve a faculty racial quota in each school corresponding to

the system-wide ratio, and ignoring all other elements is,

as of 1970, 1,826.

-18

19. If account is taken of other elements necessary

to assure quality integrated education, including qualifica

tions to teach the subject area and grade level, balance of

experience, and balance of sex, and further account is taken

of the uneven distribution of black teachers by subject

taught and sex, the total number of transfers which would be

necessary to achieve a faculty racial quota in each school

corresponding to the system-wide ratio, if attainable at all,

would be infinitely greater.

20. Balancing of staff by qualifications for subject,

and grade level, then by race, experience and sex, is educationally

desirable and important.

21. It is important for students to have a success

ful role model, especially black students in certain schools,

and at certain grade levels.

22. A quota of racial balance for faculty in each

school which is equivalent to the system-wide ratio and

without more is educationally undesirable and arbitrary.

23. A severe teacher shortage in the 1950s and

1960s impeded integration-of-facuity opportunities.

24. Disadvantageous teaching conditions in Detroit

in the 1960s— salaries, pupil mobility and transiency, class

size, building conditions, distance from teacher residence,

shortage of teacher substitutes, etc.— made teacher recruitment

and placement difficult.

25. The Board did not segregate faculty by race, but

rather attempted to fill vacancies with certified and qualified

-19-

teachers who would take offered assignments.

26. Teacher seniority in the Detroit system,

although measured by system-wide service, has been applied

consistently to protect against involuntary transfers and

"bumping" in given schools.

27. Involuntary transfers of teachers have occurred

only because of unsatisfactory ratings or because of decrease

of teacher services in a school, and then only in accordance

with balanced staff concept.

28. There is no evidence in the record that Detroit

teacher seniority rights had other than equitable purpose

or effect.

29. Substantial racial integration of staff can be

achieved, without disruption of seniority and stable teaching

relationships, by application of the balanced staff concept

to naturally occurring vacancies and increases and reductions

of teacher services.

30. The Detroit Board of Education has entered into

successive collective bargaining contracts with the Detroit

Federation of Teachers, which contracts have included provisions

promoting integration of staff and students.

The Detroit School Board has, in many other instances

and in many other respects, undertaken to lessen the impact

of the forces of segregation and attempted to advance the

cause of integration. Perhaps the most obvious one was the

adoption of the April 7 Plan. Among other things, it has

«

denied the use of its facilities to groups which practice racial

discrimination; it does not permit the use of its facilities

-20

for discriminatory apprentice training programs; it has opposed

state legislation which would have the effect of segregating

the district; it has worked to placed black students in craft

positions in industry and the building trades; it has brought

about a substantial increase in the percentage of black

students in manufacturing and construction trade apprentice

ship classes; it became the first public agency in Michigan

to adopt and implement a policy requiring affirmative act of

contractors with which it deals to insure equal employment

opportunities in their work forces; it has been a leader in

pioneering the use of multi-ethnic instructional material,

and in so doing has had an impact on publishers specializing

in producing school texts and instructional materials; and

it has taken other noteworthy pioneering steps to advance

relations between the white and black races.

In conclusion, however, we find that both the State

of Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education hav^ committed

acts which have been causal factors in the segregated condition

of the public schools of the City of Detroit. As we assay

the principles essential to a finding of de jure segregation,

as outlined in rulings of the United States Supreme Court,

they are:

1. The State, through its officers and agencies,

and usually, the school administration, must have taken some

action or actions with a purpose of segregation.

2. This action or these actions must have created

or aggravated segregation in the schools in question.

3. A current condition of segregation exists.

-21-

We find these tests to have been met in this case. We

recognize that causation in the case before us is both

several and comparative. The principal causes undeniably

have been popoulation movement and housing patterns, but

state and local governmental actions, including school board

actions, have played a substantial role in promoting

segregation. It is, the Court believes, unfortunate that we

cannot deal with public school segregation on a no-fault

basis, for if racial segregation in our public schools is an

evil, then it should make no difference whether we classify

it de jure or de facto. Our objective, logically, it seems

to us, should be to remedy a condition which we believe needs

correction. In the most realistic sense, if fault or blame

must be found it is that of the community as a whole,

including, of course, the black components. We need not

minimize the effect of the- actions of federal, state and local

governmental officers and agencies, and the actions of loaning

institutions and real estate firms, in the establishment and

maintenance of segregated residential patterns - which lead to

school segregation - to observe that blacks, like ethnic groups

in the past, have tended to separate from the larger group and

associate together. The ghetto is at once both a place of

confinement and a refuge. There is enough blame for everyone

to share.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. This Court has jurisdiction of the parties and

the subject matter of this action under 28 U.S.C. 1331(a),

1343 (3) and (4), 2201 and 2202; 42 U.S.C. 1983, 1988, and

2000d.

22-

2. In considering the evidence and in applying

legal standards it is not necessary that the Court find that

the policies and practices, which it has found to be dis

criminatory, have as their motivating forces any evil intent

or motive. Keyes v. Sch. Dist. #1, Denver, 383 F. Supp. 279.

Motive, ill will and bad faith have long ago been rejected

as a requirement to invoke the protection of the Fourteenth

Amendment against racial discrimination. Sims v. Georgia,

389 U.S. 404, 407-8.

3. School districts are accountable for the natural,

probable and forseeable consequences of their policies and

practices, and where racially identifiable schools are the

result of such policies, the school authorities bear the

burden of showing that such policies are based on educationally

required, non-racial considerations. Keyes v. Sch. Dist.,

supra, and Davis v. Sch. Dist. of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp. 734,

and 443 F .2d 573.

4. In determining whether a constitutional violation

has occurred, proof that a pattern of racially segregated

schools has existed for a considerable period of time amounts

to a showing of racial classification by the state and its

agencies, which must be justified by clear and convincing

evidence. State of Alabama v. U.S., 304 F .2d 583.

5. The Board's practice of shaping school attendance

zones on a north-south rather than an east-west orientation,

with the result that zone boundaries conformed to racial

residential dividing lines, violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

Northcross v. Bd. of Ed., Memphis, 333 F.2d 661.

-23-

6. Pupil racial segregation in the Detroit Public

School System and the residential racial segregation result

ing primarily from public and private racial discrimination

are interdependent phenomena. The affirmative obligation of

the defendant Board has been and is to adopt and implement

pupil assignment practices and policies that compensate

for and avoid incorporation into the school system the

effects of residential racial segregation. The Board's

building upon housing segregation violates the Fourteenth

Amendment. See, Davis v. Sch. Dist. of Pontiac, supra, and

authorities there noted.

7. The Board's policy of selective optional

attendance zones, to the extent that it facilitated the

separation of pupils on the basis of race, was in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp.

401, aff'd sub nom., Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F .2d 175.

8. The practice of the Board of transporting black

students from overcrowded black schools to other identifiably

black schools, while passing closer identifiably white schools,

which could have accepted these pupils, amounted to an act

of segregation by the school authorities. Spangler v. Pasadena

City Bd, of Ed., 311 F. Supp. 501.

9. The manner in which the Board formulated and

modified attendance zones for elementary schools had the

natural and predictable effect of perpetuating racial

segregation of students. Such conduct is an act of de jure

discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

U.S. v. School District 151, 286 F. Supp. 786; Brewer v. City

of Norfolk, 397 F .2d 37.

-24-

10. A school board may not, consistent with the

Fourteenth Amendment, maintain segregated elementary schools

or permit educational choices to be influenced by community

sentiment or the wishes of a majority of voters. Cooper v .

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 12-13, 15-16.

"A citizen's constitutional rights can hardly be

infringed simply because a majority of the people

choose that it be." Lucas v. 44th Gen'l Assembly

of Colorado, 377 U.S. 713, 736-737.

11. Under the Constitution of the United States

and the constitution and laws of the State of Michigan, the

responsibility for providing educational opportunity to all

children on constitutional terms is ultimately that of the

state. Turner v. Warren County Board of Education, 313 F. Supp.

380; Art. VIII, §§ 1 and 2, Mich. Constitution; Dasiewicz v .

Bd. of Ed. of the City of Detroit, 3 N.W.2d 71.

12. That a state's form of government may delegate

the power of daily administration of public schools to officials

with less than state-wide jurisdiction does not dispel the

obligation of those who have broader control to use the

authority they have consistently with the constitution. In

such instances the constitutional obligation toward the

individual school children is a shared one. Bradley v. Sch.

Bd., City of Richmond, 51 F.R.D. 139, 143.

13. Leadership and general supervision over all

public education is vested in the State Board of Education.

Art. VIII, § 3, Mich. Constitution of 1963. The duties of the

State Board and superintendent include, but are not limited to,

specifying the number of hours necessary to constitute a school

day; approval until 1962 of school sites; approval of school

construction plans; accreditation of schools; approval of loans

-25-

based on state aid funds; review of suspensions and expulsions

of individual students for misconduct [Op. Atty. Gen.,

July 7, 1970, No. 4705]; authority over transportation routes

and disbursement of transportation funds; teacher certification

and the like. M.S.A. 15.1023 (1). State law provides review

procedures from actions of local or intermediate districts

(See M.S.A. 15.3442), with authority in the State Board to

ratify, reject, amend or modify the actions of these inferior

state agencies. See M.S.A. 15.3467; 15.1919(61); 15.1919 (68b);

15.2299(1); 15.1961; 15.3402; Bridqehampton School District

No. 2 Fractional of Carsonville, Mich, v. Supt. of Public

Instruction, 323 Mich. 615. In general, the state

superintendent is given the duty " [t]o do all things necessary

to promote the welfare of the public schools and public

educational instructions and provide proper educational

facilities for the youth of the state." M.S.A. 15.3252.

See also M.S.A. 15.2299(57), providing in certain instances

for reorganization of school districts.

14. State officials, including all of the defendants,

are charged under the Michigan constitution with the duty of

providing pupils an education without discrimination with

respect to race. Art. VIII, § 2, Mich. Constitution of 1963.

Art. I, § 2, of the constitution provides:

"No person shall be denied the equal protection

of the laws; nor shall any person be denied the

enjoyment of his civil or political rights or be

discriminated against in the exercise thereof

because of religion, race, color or national

origin. The legislature shall implement this

section by appropriate legislation."

15. The State Department of Education has recently

established an Equal Educational Opportunities section having

responsibility to identify racially imbalanced school districts'

and develop desegregation plans. M.S.A. 15.3355 provides

that no school or department shall be kept for any person or

persons on account of race or color.

16. The state further provides special funds to

local districts for compensatory education which are administered

on a per school basis under direct review of the State Board.

All other state aid is subject to fiscal review and accounting

by the state. M.S.A. 15.1919. See also M.S.A. 15.1919 (68b),

providing for special supplements to merged districts "for the

purpose of bringing about uniformity of educational opportunity

for all pupils of the district." The general consolidation law

M.S.A. 15.3401 authorizes annexation for even noncontiguous

school districts upon approval of the superintendent of public

instruction and electors, as provided by law. Op. Atty. Gen.,

Feb. 5, 1964, No. 4193. Consolidation with respect to so-

called "first class" districts, i.e., Detroit, is generally

treated as an annexation with the first class district being

the surviving entity. The law provides procedures covering

all necessary considerations. M.S.A. 15.3184, 15.3186.

17. Where a pattern of violation of constitutional

rights is established the affirmative obligation under the

Fourteenth Amendment is imposed on not only individual school

districts, but upon the State defendants in this case.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358, U.S. 1; Griffin v. County School Board

of Prince Edward County, 337 U.S. 218; U.S, v. State of Georgia,

Civ. No. 12972 (N.D. Ga., December 17, 1970), rev1d on other

grounds, 428 F .2d 377; Godwin v. Johnston County Board of

Education, 301 F. Supp. 1337; Lee v. Macon County Board o_f

Education, 267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala.), aff’d sub nom.,

27-

Wallace v. U.S., 389 U.S. 215; Franklin v. Quitman County-

Board of Education, 288 F. Supp. 509; Smith v. North Carolina

State Board of Education, No. 15,072 (4th Cir., June 14, 1971).

The foregoing constitutes our findings of fact and

conclusions of law on the issue of segregation in the public

schools of the City of Detroit.

Having found a de jure segregated public school

system in operation in the City of Detroit, our first step,

in considering what judicial remedial steps must be taken,

is the consideration of intervening parent defendants'

motion to add as parties defendant a great number of Michigan

school districts located out county in Wayne County, and in

Macomb and Oakland Counties, on the principal premise or

ground that effective relief cannot be achieved or ordered in

their absence. Plaintiffs have opposed the motion to join

the additional school districts, arguing that the presence

of the State defendants is sufficient and all that is required,

even if, in shaping a remedy, the affairs of these other

districts will be affected.

In considering the motion to add the listed school

districts we pause to note that the proposed action has to

do with relief. Having determined that the circumstances of

the case require judicial intervention and equitable relief,

it would be improper for us to act on this motion until the

other parties to the action have had an opportunity to submit

their proposals for desegregation. Accordingly, we shall not

rule on the motion to add parties at this time. Considered

as a plan for desegregation the motion is lacking in specifity

-28-

and is framed in the broadest general terms. The moving party-

may wish to amend its proposal and resubmit it as a com

prehensive plan of desegregation.

In order that the further proceedings in this cause

may be conducted on a reasonable time schedule, and because

the views of counsel respecting further proceedings cannot but

be of assistance to them and to the Court, this cause will be

set down for pre-trial conference on the matter of relief.

The conference will be held in our Courtroom in the City of

Detroit at ten o'clock in the morning, October 4, 1971.

DATED: September 27 , 1971.

-2 9-