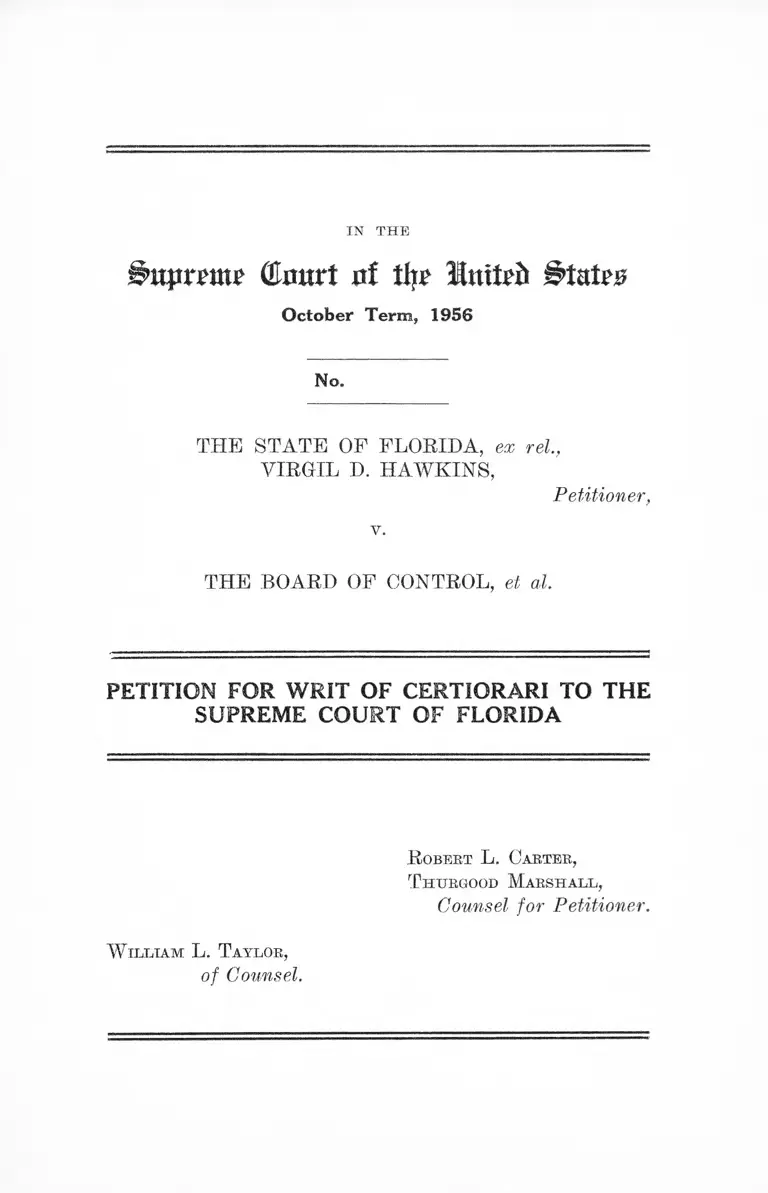

Florida v. Board of Control Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Florida

Public Court Documents

March 8, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Florida v. Board of Control Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Florida, 1957. 3be37a03-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/87e6d5c8-b991-4bed-9736-7aee5db5dbf8/florida-v-board-of-control-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-florida. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

§>upr£uu> ( to r t rtf % Hnitrft Stairs

O ctober Term , 1956

IN T H E

No.

THE STATE OF FLORIDA, ea; rel.,

VIRGIL I). HAWKINS,

Petitioner,

THE BOARD OF CONTROL, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

R obert L. Carter ,

T hurgood M a rshall ,

Counsel for Petitioner.

W illia m L. T aylor,

of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Petition for Writ of Certiorari ..............................

Opinion Below...................................................

Jurisdiction.........................................................

Questions Presented...........................................

Statement ...........................................................

Reasons for Allowance of the Writ ..................

Conclusion..................................................................

A p p e n d ix — Opinion of the Supreme Court of Florida

1

1

2

3

6

8

9

Table of Cases Cited

Betts v. Brady, 316 U. S. 455 .................................. 2

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 .............. 6

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ............................. 6

Cole v. Arkansas, 338 U. S. 345 .............................. 2

Department of Banking v. Pink, 317 U. S. 264 ....... 2

Ex parte Endo, 323 IT. S. 283 .................................... 7

Jones National Bank v. Yates, 240 TJ. S. 541............ 2

Magwire v. Tyler, 17 Wall. 253 .................................. 2, 7

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304 .................. 2, 7

McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316....................... 2

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 IT. S.

637 ........................................................................... 5, 6

Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 328 TJ. S.

373 ........................................................................... 7

Osborn v. The Bank of the United States, 9 Wheat.

738 ......................................................... ; ............... 6

11

PA G E

Parker v. Illinois, 333 U. S. 570 ................................ 2

Poindexter v. Greenhow, 114 U. S. 270 .................... 2

Republic Natural Gas Co. v. Oklahoma, 334 U. S.

62 ............................................................................. 2

Richfield Oil Corp. v. State Board of Equalization,

329 U. S. 6 9 ........................................... ................. 2

Sipuel v. University of Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631 . . . . . 5, 6

Stanley v. Schwalby, 162 U. S. 255 ......................... 2

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ............................. 5, 6

Urie v. Thompson, 337 U. S. 163............................... 2

Williams v. Bruffy, 102 U. S. 248 ............................. 2, 7

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 ......................... 6

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 ......................... 7

Statutes Cited

Title 28, United States Code:

Section 1257(3) .................................................. 2

Section 1651(a) ....... .......................................... 1, 2, 8

Section 2106 ........................................................ 1, 2, 8

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment .................................... 2

O ther A uthorities C ited

Hart and Wechsler, The Federal Courts and the

Federal System 240 (1st ed. 1953) ...................... 2

1 Warren, The Supreme Court in United States

History 433 (1922) ...................... 7

IN ' T H E

© m t r t u f t i p I n t t e f c

O ctober Term , 1956

No.

-----------— -------------- - o ---------------------------------

T h e S tate of F lorida , ex rel.,

V ir g il D . H a w k in s ,

Petitioner,

v.

T h e B oard of C o ntrol , et al.

------------------------- o----- ------ --------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Florida entered in

the above-entitled cause on March 8, 1957.

Further, petitioner prays that pursuant to Title 28,

United States Code, Sections 1651(a) and 2106, this Court

enter the judgment that the Supreme Court of Florida

should have entered after this Court vacated and remanded

a prior judgment of the Supreme Court of Florida on

March 12, 1956.

Opinion Relow

The opinion of the court below last entered in this cause

and now before this Court on this petition for writ of

certiorari was entered on March 8, 1957, and is reported

at 93 So. 2d 354. It is printed in the Appendix hereto

at pp. 9-33.

9

Jurisd iction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1257 (3). Petitioner asserted

rights and privileges guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States and through

out the long history of this litigation, those rights have

been repeatedly asserted and preserved. This Court will

issue a writ of certiorari to resolve doubts about whether

its mandate in an earlier decision has been obeyed by the

state court. Cole v. Arkansas, 338 U. S. 345, 347.

The judgment below was final, Betts v. Brady, 316 U. S.

455; cf. Republic Natural Gas Co. v. Oklahoma, 334 U. S.

62, 68; Parker v. Illinois, 333 U. S. 570, 576-577; and is

reviewable by this Court notwithstanding any designation

given it by the state court, Department of Banking v. Pink,

317 U. S. 264, 268; Richfield. Oil Corp. v. State Board of

Equalization, 329 U. 8. 69, 72.

This Court has jurisdiction under Title 28, United States

Code, Sections 1651(a) and 2106 to enter its own judgments,

and in the past has issued such judgments, especially in

situations where a state court has failed to act in con

formity with a prior mandate of this Court. Martin v.

Hunter's Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304; McCulloch v. Maryland,

4 Wheat. 316, 437; Mag-wire v. Tyler, 17 Wall. 253, 289-

290; Williams v. Bruffy, 102 U. 8. 248; cf. Stanley v.

Schwalby, 162 U. S. 255, 280-282. See Hart and Wechsler,

The Federal Courts and the Federal System 240 (1st ed.

1953).1

1 Similarly, in a number of cases which did not involve any viola

tion of a prior mandate, this Court has acted in aid of jurisdiction

by remanding the case to the state court with orders to enter a spe

cific judgment for one of the parties. Stanley v. Schwalby, 162 U. S.

255; Poindexter v. Greenhow, 114 U. S. 270, 306; Jones National

Bank v. Yates, 240 U. S. 541, 563; Urie v. Thompson, 337 U. S.

163, 196.

3

Questions Presented

May the court below refuse to issue a writ of mandamus

ordering petitioner’s admission to the University of Florida

Law School on the ground that to do so at this time ‘1 would

tend to work a serious public mischief?”

Did the court below, in refusing to issue the writ for

the reasons stated, act in violation of the mandate issued

by this Court on March 12, 1956?

Should this Court enter its own judgment ordering the

immediate admission of petitioner to the University of

Florida in order to secure compliance with its mandate of

March 12, 1956?

Statem ent

The cause originated in April, 1949. Petitioner was

one of four applicants who sought admission to the pro

fessional and graduate schools of the University of Florida.

Petitioner seeks entrance to the school of law. On May 13,

1949, petitioner was advised that his admission to the

University of Florida was prohibited because he was a

Negro, and the Board of Control offered to pay his tuition

to an institution of his choice outside the state. Petitions

for alternative writs of mandamus were filed in the Supreme

Court of the State of Florida and were granted (R. 8).

On August 1, 1950, the court below entered its first

judgment and ruled that the Board of Control, in ordering

the establishment of a school of law and other graduate

courses at Florida A. and M. College for Negroes, and in

offering to provide out-of-state scholarship aid to peti

tioner pending establishment of these segregated educa

tional facilities, had fully satisfied the state’s constitutional

obligation to furnish equal educational opportunities to

petitioner and other Negroes similarly situated. The court

4

refused to enter a final order but retained jurisdiction in

order to permit tlie parties to seek further relief at some

later date (R. 69-70). The opinion is reported at 47 So.

2d 608. On May 16, 1951, petitioner filed a motion for

peremptory writ of mandamus (R. 72). On June 15, 1951,

the court below denied the peremptory writ (R. 75). This

opinion is reported at 53 So. 2d 116. Petitioner filed a

petition for writ of certiorari in this Court. This Court

refused to grant certiorari on the ground that no final

judgment had been entered, 342 U. S. 877.

On June 7,1952, petitioner filed a motion for peremptory

writ and for final judgment in the court below (R. 83).

On August 1, 1952, the Supreme Court of Florida entered

final judgment in this case denying petitioner’s motion for

peremptory writ, quashing the alternative writs of man

damus previously issued and dismissing the cause (R. 96).

This opinion is reported at 67 So. 2d 162. When the cause

was brought here a second time, this Court granted the

petition for writ of certiorari, vacated the judgment below,

and remanded the cause for ‘ ‘ consideration in the light of

the Segregation Cases decided May 17, 1954 . . . and con

ditions that now prevail.” 347 U. S'. 971.

On July 31, 1954, the Supreme Court of Florida ordered

the petitioner to amend his petition so as to place before

the court the issues raised by the original petition in the

light of the School Segregation Cases, decided May 17,

1954, and conditions that now prevail (R. 105). On Sep

tember 30, 1954, an amended petition for alternative writ

of mandamus was filed in the court below (R. 108), and

thereafter, an amended answer was filed by respondents

(R. 97)—all pursuant to the court’s instruction. On Octo

ber 19, 1955, a new judgment was entered, declaring the

exclusion of petitioner from the University of Florida

solely because of his race unconstitutional, but appointing

a commissioner to take evidence pursuant to which the

5

court below would determine when and under what cir

cumstances petitioner might be admitted to the University

of Florida in the indeterminate future (R. 142). This, the

fourth opinion, is reported at 83 So. 2d 20.

Although the judgment below was not final, petitioner

sought in this Court the issuance of a writ of certiorari or

one of the common law writs. This petition was denied,

but at the same time this Court recalled and vacated its

prior order of May 24, 1954, and entered a new order, re

manding the cause. Citing McLaurm v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 U. S. 637; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629;

and Sipuel v. University of Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631, this

Court stated that there was no reason for delay and that

petitioner was entitled to prompt admission to the law

school under the rules and regulations applicable to other

qualified candidates, 350 U. S. 413, reh. denied 351 U. S.

915.

On May 25, 1956 the Commissioner, appointed by the

court below on October 19, 1955 to report when conditions

would warrant petitioner’s admission, submitted his report

(R. 169).

On June 20, 1956, petitioner again sought in the court

below the issuance of a peremptory writ of mandamus

ordering his admission to law school (R. 134). Hearing

was held in the court below on petitioner’s motion on Sep

tember 4, 1956. On March 5, 1957, the court below denied

a motion made by respondent to refer the cause to a com

missioner (R. 674). On March 8, 1957, nearly a year after

this Court entered its last order, the court below entered

the present judgment, denying petitioner’s motion for a

peremptory writ (R. 676).

To support its decision, the court reiterated the ground

stated in its opinion of October 19, 1955, that mandamus

was a discretionary writ which the court could refuse to

issue where to do so “ would tend to work a serious public

mischief.” In concluding that this was the case here, the

6

court relied upon evidence adduced by respondent in hear

ings held by the commissioner appointed by the court in

its decision of October 19, 1955. The court held that it

was not precluded by this Court’s order of March 12, 1956,

from, denying petitioner’s motion on the grounds stated.

Finally, the court below ruled that petitioner might renew

his motion “ when he is prepared to present testimony

showing that his admission can be accomplished without

doing great public mischief.” This opinion is reported at

93 So. 2d 354.

Reasons for A llow ance of the W rit

1. Petitioner is entitled to an order which will effectu

ally secure his immediate admission to the University of

Florida law school. More than 7 years have elapsed since

petitioner first sought relief in the court below to obtain

admission to law school and that relief has yet to be

granted. The nature and extent of petitioner’s consti

tutional right to an unsegregated legal education has been

clear since this Court decided SweaM v. Painter, 339 U. S.

629, and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. 8.

637 in 1950. Petitioner’s right is “ personal and present,”

and he is entitled to prompt admission under the rules and

regulations applicable to other qualified candidates. Sweatt

v. Parnter, supra; Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631, 633; cf. McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents, supra. A court may not refuse

to give effect to rights protected by the Constitution on the

ground that it is simply exercising its discretion to decline

to afford relief. See e.g., Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S.

375, 383; Osborn v. The Bank of the United States, 9 Wheat.

738, 866. Neither community opposition, nor threats of

violence and hostility can excuse a denial of constitutional

rights or a delay in vindicating them. Buchanan v. Warley,

245 U. S. 60, 80; Brown v. Board of Education, 349 IT. S.

294, 300; cf. Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 328

U. S. 373, 380; Ex parte Endo, 323 U. 8. 283, 302; Tick Wo

v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 374. Yet the court below persists

in its refusal to afford relief to petitioner for the very

reasons declared judicially non-cognizable by this Court

in an unbroken line of decisions.

2. The judgment of the court below is in direct conflict

with the order issued by this Court on March 12, 1956, in

this case. Even if it be assumed, arguendo, that a state

court is free to seek new independent grounds for decision

after the issuance of a mandate by this Court, that is not

the case here. By the court’s own admission (R. 680) all

of the grounds now advanced by it for denying the writ

sought by petitioner were contained in its opinion of Octo

ber 19, 1955, and thus were necessarily before this Court

when the order of March 12, 1956, was issued. In that

order, this Court said, “ As this case involves the admis

sion of a Negro to a graduate professional school, there is

no reason for delay. He is entitled to prompt admission

under the rules and regulations applicable to other quali

fied candidates,” 350 U. S. 413. In the face of this, the

court below continues to insist that the reasons for delay

that it urged prior to March 12, 1956, are still valid.

3. Not since the early days of the Republic has the

authority of this Court to interpret the Constitution been

challenged in so flagrant a manner by a court of inferior

jurisdiction. In those early tests, this Court met challenges

to its authority patiently yet firmly by entering judgments

to effectuate its opinions. See Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee,

supra; Magwire v. Tyler, supra; Williams v. Bruffy, supra.

Authorities attribute the durability of the Union in large

part to the firm manner in which this Court met these

threats. See e.g., 1 Warren, The Supreme Court in United

States History, 433, 450-451 (1922). Petitioner seeks only to

exercise rights guaranteed by the Constitution and declared

8

in unmistakable terms by this Court. All efforts by peti

tioner to secure protection of these rights in the court

below have failed, and there is no indication that such pro

tection is forthcoming in the foreseeable future. Thus, peti

tioner’s only recourse is an appeal to this Court to grant

this petition and to exercise its authority under Title 28,

United States Code, Sections 1651(a) and 2106 and enter

its own order directly to the Board of Control ordering

petitioner’s admission to the University of Florida.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the reasons hereinabove stated , it is

respectfully subm itted th a t this petition for w rit of cer

tio rari should be g ranted and th a t this Court should

en ter its own judgm ent ordering petitioner’s adm ission

w ithout fu rther delay to the U niversity of F lorida Law

School.

Respectfully submitted,

W il l ia m L. T aylor,

of Counsel.

R obeet L. Ca etee ,

T hurgood M a rsh a ll ,

Counsel for Petitioner.

9

A PPEND IX

(O pinion of th e Suprem e Court of Florida

Filed M arch 8, 1957)

R oberts, J .:

This litigation is concerned with the rights of the Rela

tor, a Negro, to be admitted to the University of Florida

Law School, provided he meets the entrance requirements

applicable to all students. The history of the litigation is

set forth in State ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control

(Fla. 1955) 83 So. 2d 20, our latest decision in the contro

versy, referred to hereafter as the “ 1955 decision.”

Our 1955 decision was entered in response to the

mandate of the United States Supreme Court in State

ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control (May 1954) 347

U. S. 971, directing this court to reconsider its decision

in State ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control (Fla.

1952) 60 So. 2d 162 (the “ 1952 decision” hereafter),

“ in the light of the Segregation Cases decided May

17, 1954, Brown v. Board, of Education, etc. [347 U. S. 483]

and conditions that now prevail.” Since this court has

held in a long line of decisions that it is bound by the

decisions of the United States Supreme Court “ construing

the meaning and effect of acts of Congress and those pro

visions of the national Constitution which restrict the

powers of the states,” Miami Home Milk Producers Ass’n

v. Milk Control Board (1936) 169 So. 541, 124 Fla. 797, we

held in our 1955 decision, under the authority of Brown v.

Board of Education, etc., supra, 347 U. S. 483, that the

Relator could not be denied admission to the University of

Florida Law School solely because of his race. In the

exercise of our discretion, however, we decided to withhold

the issuance of a peremptory writ of mandamus in the

cause, pending a subsequent determination of law and fact

as to the time when the Relator should be admitted to that

institution; and the Honorable John A. H. Murphree, Resi

10

dent Circuit Judge of the circuit in which the University is

located, was appointed as the commissioner of this court to

take testimony on behalf of the Relator and the Respond

ents, members of the Board of Control, relating to the

factual issue. Our decision in this respect was based on

two considerations, one a federal and the other a state

ground: (1) the application to the controversy of the for

mula set out in the so-called “ implementation decision,”

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 295;

and (2) the exercise of our traditional power as a state

court to decline to issue the extraordinary writ of man

damus if to do so would tend to work a serious public

mischief. City of Safety Harbor v. State (1939) 136 Fla.

636, 187 So. 173; State ex rel. Carson v. Bateman, 131 Fla.

625, 180 So. 22; State ex rel. Gibson v. City of Lakeland,

126 Fla. 342, 171 So. 227; State ex rel. Bottome v. City of

St. Petersburg, 126 Fla. 233, 170 So. 730.

The Relator then filed a petition for certiorari in the

United States Supreme Court to review our 1955 decision

on the ground that the decision in the Brown case, 347 U. S.

483, did not apply to ‘ ‘ State junior colleges, colleges, gradu

ate and professional schools.” The court disposed of this

petition by a short but not entirely unambiguous opinion,

dated March 12, 1956, reading as follows:

“ P er C u r ia m .

“ The Petition for certiorari is denied.

“ On May 24, 1954, we issued a mandate in this

case to the Supreme Court of Florida. 347 U. S. 971.

We directed that the case be reconsidered in light of

our decision in the Segregation Cases decided May

17, 1954, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483. In doing so, we did not imply that decrees

involving graduate study present the problems of

public elementary and secondary schools. We had

theretofore, in three cases, ordered the admission of

Negro applicants to graduate schools without dis

11

crimination because of color. Sweatt v. Painter, 339

II. 8. 629; Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the TJni-

versity of Oklahoma, 332 IJ. S. 631; cf. McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, 339

U. S. 637. Thus, our second decision in the Brown

case, 349 IJ. 8. 294, which implemented the earlier

one, had no application to a case involving a Negro

applying for admission to a state law school. Ac

cordingly, the mandate of May 24, 1954, is recalled

and is vacated. In lieu thereof, the following order

is entered:

“ P e e C u e ia m : The petition for writ of certiorari

is granted. The judgment is vacated and the case

is remanded on the authority of the Segregation

Cases decided May 17, 1954, Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483. As this case involves the

admission of a Negro to a graduate professional

school, there is no reason for delay. He is entitled

to prompt admission under the rules and regulations

applicable to other qualified candidates. Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U. 8. 629; Sipuel v. Board of Regents

of the University of Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631; cf.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher

Education, 339 IT. S. 637.”

The cause is now before this court on the Relator’s

motion for a peremptory writ of mandamus to compel the

Respondents to admit him to the University of Florida Law

School, his contention being that the above-quoted opinion

entitles him to immediate admission, provided he is other

wise qualified, without regard to the outcome of the factual

study which was in progress at the time of the filing of his

motion and which has now been concluded.

There can be no doubt that, by revising its May 1954

mandate directed to our 1952 decision in the manner above

noted, the Supreme Court of the United States neatly, albeit

laconically, cut off the federal prop that supported, in part,

our 1955 decision. But it will have been noted that the

12

opinion stated that “ [t]he petition for certiorari is de

nied” , presumably referring to our 1955 decision; and,

this being so, our 1955 decision still stands, nonetheless

firmly, on the state ground mentioned therein and referred

to above.

Indeed, it is unthinkable that the Supreme Court of the

United States would attempt to convert into a writ of right

that which has for centuries at common law and in this

state been considered a discretionary writ; nor can we

conceive that that court would hold that the highest court

of a sovereign state does not have the right to control the

effective date of its own discretionary process. Yet, this

would be the effect of the court’s order, under the interpre

tation contended for by the Relator. We will not assume

that the court intended such a result.

In what appears to be a progressive disappearance of

State sovereignty, it is interesting to read certain decisions

(among others) which the United States Supreme Court

has handed down in recent months. See: Railway Em

ployees Dept., etc. et al. v. Hanson, et al. (May 1956) —

U. S. — , 100 L. Ed. (advance) p. 638, holding that a

union shop agreement negotiated between certain railroads

and certain organizations of employees of such railroads

which had been authorized by an act of the Congress super

seded the right-to-work provisions of the Constitution of

the State of Nebraska and the state statutes enacted pur

suant thereto; Dantan George Rea v. United States of

America (January 1956) 350 U. S. 214, 100 L. Ed. (ad

vance) p. 213, holding that it was within the power of the

federal courts to enjoin an officer of the executive depart

ment of the federal government from testifying in a state

court in a case involving a violation of a criminal statute

of that state; Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Steve

Nelson (April 1956) 350 U. S. 497, 100 L. Ed. (advance)

p. 415, outlawing antisedition laws in 42 states, Alaska

and Hawaii; Griffin et al v. People of the State of Illinois

(April 1956) — U. S. — , 100 L. Ed. (advance) p. 483,

requiring the states to finance appeals by penniless per

sons convicted of crimes; Slochower v. Board of Higher

13

Education of the City of New York (April 1956) 350 U. S.

551, 100 L. Ed. (advance) p. 449, limiting the power of

states and cities to discharge public employees when they

plead the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination in

duly authorized inquiries affecting the general welfare;

Broivder et al. v. Gayle et als., 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D.

Ala. 1956), affirmed by the Supreme Court, 77 S. Ct. 145,

holding invalid statutes and ordinances requiring the segre

gation of the white and colored races in motor buses oper

ating in the City of Montgomery, Alabama.

It is a “ consummation devoutly to be wished” that the

concept of “ states’ rights” will not come to be of interest

only to writers and students of history. Such concept is

vital to the preservation of human liberties now. And

whatever one’s ideology may be—whether one is a strong

defender of state sovereignty or an equally fervent advo

cate of centralized government—we think the great major

ity of persons would agree that if the death knell of this

fundamental principle of Jeffersonian democracy is to be

tolled, the bell should be rung by the people themselves as

the Constitution contemplates. President Lincoln’s words

of warning are just as true today as they were almost a

century ago, when he said in his first inaugural address

on March 4, 1861:

“ If the policy of the government upon vital ques

tions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably

fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court . . . the

people will have ceased to be their own rulers, hav

ing to that extent practically resigned their govern

ment into the hands of that eminent tribunal.”

And we do not feel it is amiss to refer to the following

remarks made by George Washington in his “ Farewell

Address” :

“ If, in the opinion of the people, the distribution

or modification of the constitutional powers be in

14

any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an

amendment in the way which the Constitution desig

nates. But let there be no change by usurpation;

for though this, in one instance, may be the instru

ment of good, it is the customary weapon by which

free governments are destroyed.”

But we repeat that, despite these recent decisions, we

cannot attribute to the Supreme Court an intention to abro

gate the rule which denies to federal courts the right to

regulate or control long-established rules of practice and

procedure adopted by state courts for the administration

of justice therein. Cf. Naim v. Naim (Va. 1956) 90 S. E.

2d 849, in which the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

declined to remand a cause to a lower court, as directed by

mandate of the United States Supreme Court, because to

do so “ would be contrary to [the] fixed rules of practice

and procedure” of the Virginia courts, as well as the

statute law of that state. A motion to recall the mandate

and to set the case down for oral argument upon the merits,

or in the alternative, to recall and amend the mandate was

denied by the United States Supreme Court for the reason

that the decision above referred to, 90 S. E. 2d 849, “ leaves

the case devoid of a properly presented federal question.”

Naim v. Naim (March 12, 1956) — U. S. — , 100 L. Ed.

(advance) p. 352. A fortiori, we cannot assume that the

Supreme Court intended to deprive the highest court of

an independent sovereign state of one of its traditional

powers, that is, the right to exercise a sound judicial discre

tion as to the date of the issuance of its process in order

to prevent a serious public mischief. As recently as June

4, 1956, in United Automobile, Aircraft and Agricultural

Implement Workers of America, et al. v. Wisconsin Em

ployment Relations Board et al., — U. S. — , the Supreme

Court recognized the “ dominant interest” of a state in

preventing violence. It there said: “ The States are the

natural guardians of the public against violence. It is the

15

local communities that suffer most from the fear and loss

occasioned by coercion and destruction. We would not in

terpret an act of Congress to leave them powerless to avert

such emergencies without compelling directions to that

effect.” We are cognizant of our duty to compel Relator’s

admission to the University of Florida Law School “ with

out delay” , if it is feasible to do so at this time; but we

have an equally compelling duty to perform in respect to

the public peace and a long-established state judicial pro

cedure by which to perform it. We point out, additionally,

that the Relator, having a choice between a federal and a

state court, selected this court as the forum in which to try

his cause; he thereby selected the rules of practice and

procedure long established in this jurisdiction. We have no

doubt that the Supreme Court intended that we should ad

here to such procedure in the instant controversy. The

Relator’s contention in this respect cannot, therefore, be

sustained.

We come now to the question of whether the facts, as

developed under the guidance of this court’s commissioner,

require the immediate admission of the Relator to the

University of Florida Law School, provided he meets the

entrance requirements, i t might be noted that the Relator

had due notice and an opportunity to be heard at the hear

ings scheduled by the commissioner. He did not appear

nor did he present any testimony in support of his right to

immediate admission. Moreover, the history of this con

troversy leads us to believe that the Relator does not, in

fact, have a genuine interest in obtaining a legal education.

He was given an opportunity to secure a legal education

outside this state under the Regional Education Plan, but

declined; he was given an opportunity to attend the Uni

versity of Florida Law School, temporarily, if law facilities

were not available at the Florida Agricultural & Mechani

cal University, but declined; he was then given an oppor

tunity to attend the law school at the Florida Agricultural

& Mechanical University, but declined. And, as noted, ho

1 6

was given an opportunity to appear before the court’s com

missioner and offer evidence in support of his right to im

mediate admission to the University of Florida Law School,

but declined.

It should be noted that the Law School at the University

of Florida is an integral part of that institution. A law

student is not in a class separate and apart from all other

University students—he is a University student just as

much as those entering the engineering school or the edu

cational school or the architectural school, and entitled to

participate in all campus activities.

Against this background, we have considered the evi

dence adduced by the Respondents which, in the state of the

record here, must constitute the basis for the exercise of

our discretion in the matter. The factual material on file

in this court reflects a prodigious amount of work by the

commissioner and the Respondents or those acting in their

behalf. It is not contended—nor could it be—that there

was even a modicum of bias on the part of any person

involved in the work of assembling the data here presented

nor in the formulation of the questionnaires which were

the basic media by which much of the information was

obtained. The survey is completely objective and as accu

rate and comprehensive as the time available for the study

would permit. The testimony of the witnesses shows no

bias and reflects only a sincere desire to do whatever is

best for all concerned.

The survey conducted under the guidance of the court’s

commissioner shows, among others, that a substantial num

ber of students and a substantial number of the parents of

students state that they expect to take action—which appar

ently is positive action—to persuade Negro students to

leave the University or make it so unpleasant for them that

they will move out of a dormitory room or out of a class

or out of a cafeteria or otherwise stop using the facilities

of the University of Florida, should integration occur. It

was also shown that 41 percent of the parents of students

17

now in our white universities would cause them to drop out

of those schools or transfer to another school; and that

62 percent of the parents of white 1956 high school gradu

ates would send their children elsewhere than to our white

state institutions, if we have enforced integration. There

would be loss of revenue to our white institutions from

grants, from activities on the part of the alumni of those

institutions in support of their financial affairs, and from

students moving out of dormitories (many of which are

being paid for out of revenue certificates), if we have in

tegration. Those institutions would lose the support of

52 percent of their alumni, if integration occurs, which

would seriously impair the financial support to be expected

from our state legislature. Integration would unques

tionably result in the abandonment of substantially all of

the graduate work now being offered at the Florida Agri

cultural & Mechanical University because it would be an

unnecessary duplication of the same courses offered at the

University of Florida or at Florida State University.

Our study of the results of the survey material to the

question here, and other material evidence, leads inevi

tably to the conclusion that violence in university com

munities and a critical disruption of the university system

would occur if Negro students are permitted to enter the

state white universities at this time, including the Law

School of the University of Florida, of which it is an inte

gral part. This court has an opportunity to prevent the

incidents of violence which are, even now, occurring in

various parts of this country as a result of the states’

efforts to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision in the

Brown case. We quote with approval that part of the

language of Mr. Justice Hobson in his special concurring

opinion in which he said “ the testimony which was taken

at the direction of this court by the Honorable John A. H.

Murphree, and which is now before us for consideration,

was not in the record when the Supreme Court of the United

States said ‘there is no reason for delay’. This testimony,

18

as well as the revealing incidents (of which we may take

judicial notice) which have occurred since the repudiation

of the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine, convinces me that the

immediate admission of relator to the University of Flor

ida College of Law would result in great public mischief.”

The homely expression, “ An ounce of prevention is worth

a pound of cure,” is especially applicable to the situation

here—involving, as it does, the public welfare of all our

people.

In the exercise of what we sincerely believe to be sound

judicial discretion, we have decided that the relator’s mo

tion for a peremptory writ should be denied, but without

prejudice to the right of relator to renew his motion when

he is prepared to present testimony showing that his ad

mission can be accomplished without doing great public

mischief. For the reasons stated, the entry of a final judg

ment is deferred until further order of the court.

It is so ordered.

T h o bn a l and O’C o n n e l l , Concur.

T eb b ell , G.J., a n d H obson , Concurs sp e c ia lly .

T hom as and D r e w , J J Dissent.

T er r ell , C.J., Concurring:

I concur in the opinion of Mr. Justice Eoberts, particu

larly with that part relating to the power of this and other

states to control their process when public mischief is im

minent. This doctrine is all the more compelling when long

settled rules relating to the administration of justice and

the prevention of violence are brought in question. His

torically, individuals, as well as states, have interposed

action to thwart the inroads of Federal authority not so

much for delay as to preserve what was deemed to be the

most precious of American ideals. In a free democracy

the decisions of courts, even the Supreme Court of the

19

United States, have never been considered sacrosanct or

free from challenge.

In 1798 Jefferson and Madison on behalf of Virginia

and Kentucky challenged the constitutional validity of the

Federal sedition law. They contended that the law was not

only unconstitutional, that it was in violation of the com

pact with the states and would continue so until effectuated

by constitutional amendment. No attempt was made to

force obedience on the part of Kentucky and Virginia but

in 1801 Jefferson, author of the Kentucky resolution, was

elected president of the United States.

In 1832, South Carolina nullified the Federal tariff act

passed that year and nothing was done to force obedience

but a new tariff act was passed forthwith. In 1838, the

State of Georgia was ordered by the Supreme Court of the

United States not to remove the Cherokee Indians beyond

the state. This was the famous case in which President

Andrew Jackson injected himself into the picture and issued

his famous pronouncement, “ John Marshall has made his

decision, now let him enforce it.” The order was not

obeyed. The State of Wisconsin refused to follow the

order of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision

promulgated prior to the Civil War. Georgia and Virginia

have recently but respectfully declined to follow orders of

the Supreme Court relying on control of their own process

and the fact that there was still a modicum of sovereignty

in the states that they had a right to invoke. In none of

the foregoing incidents was any attempt made to coerce

the states.

Some anthropologists and historians much better in

formed than I am point out that segregation is as old as

the hills. The Egyptians practiced it on the Israelites; the

Greeks did likewise for the barbarians; the Romans segre

gated the Syrians; the Chinese segregated all foreigners;

segregation is said to have produced the caste system in

India and Hitler practiced it in his Germany, but no one

ever discovered that it was in violation of due process until

20

recently and to do so some of the same historians point out

that the Supreme Court abandoned the Constitution, prece

dent and common sense and fortified its decision solely with

the writings of Gunner Myrdal, a Scandinavian sociologist.

What he knew about constitutional law we are not told nor

have we been able to learn.

Such is in part the predicate on which the states are

resisting integration. They contend that since the Supreme

Court has tortured the Constitution, particularly the wel

fare clause, the interstate commerce clause, the Ninth and

Tenth Amendments, the provisions relating to separation

of state and federal powers, and the powers not specifically

granted to the Federal government being reserved to states,

they have a right to torture the court’s decision. Whatever

substance there may be to this contention, it is certain that

forced integration is not the answer to the question. It is

a challenge to freedom of action that is contrary to every

democratic precept. It is certain that attempts at integra

tion by court order have engendered more strife, tension,

hatred and disorder than can be compensated for in gen

erations of attempt on the part of those who are forward

looking and want to do so. They have done more to break

down progress and destroy good feeling and understand

ing between the races than anything that has taken place

since emancipation. Social progress in any time is not

measured by legislative acts and decree; it is measured by

qualitative citizenship.

The seventeen states committed to segregation have the

material stake in this question. They have spent billions on

separate schools, hospitals and other institutions in the

attempt to provide “ separate but equal” facilities and

opportunities for both races in reliance on what they under

stood to be the law. Violence has arisen everywhere and

continues to arise account of attempts to comply with the

Federal Courts’ orders and the end is not yet. These

“ states are the natural guardians of the public against

violence” ; they know the reasons for it; they are fully

21

aware that such tensions are grounded in the attempt of

the Federal Courts at a form of enforced integration that

is contrary to every precept that activates the need for law

in this country.

Human nature may not be what it should be but such

as it is, we are compelled to take it into account. The prob

lem presented is more social than legal. In fact law is not

the conclusive answer. Social advancement has never been

measured by legal formulas and human nature has not

reached the point where human ingenuity will not find a

road to bypass laws and regulations which attempt to abro

gate long settled social standards. To be enforced in a

democracy law must always follow and never precede a

felt necessity for it. This was never better illustrated than

by what is now being done to bypass Federal integration

orders and what happened to national prohibition in the

thirties. Surveys made in Washington City schools where

integration has been attempted for at least two years also

fortify this premise. If, as pointed out in the opinion of

Mr. Justice Roberts, the Supreme Court of the United

States recognizes that the “ dominant interest” of the state

is to prevent violence and the record here points the road

to violence, that in itself is enough for this court to with

hold the issuance of its mandate. The record is best forti

fied by what is or has been taking place in more than a

half dozen states.

Then it has been revealed that these riots and outbreaks

were not activated by local people but by interlopers from

other places, in other words, social boll weevils, fruit flies,

potato bugs, bean beetles, cane borers and other pests that

we institute quarantines or other rigid measures against to

get rid of. It takes time to do this and then it must be

done by legal processes, otherwise we invoke that which is

at least in the nature of the communist manifesto to enforce

democratic processes. The problem is a different one in

every state and in this state the governor and the educa

tional authorities are pursuing legal methods to solve the

22

problem. After all is said the big question is not one of

defying constituted authority, it is one of finding a way of

solving a serious problem recently thrust upon the states

with segregated schools and at the same time preserve

their traditions, their moral, social, cultural and educa

tional standards.

For the purpose of fortifying the premises discussed

in the preceding paragraphs, it is pertinent to point out

that the legislature on recommendation of the Fabisinski

Committee, appointed by the governor, to recommend a

method to best handle the segregation question in a legal

way, has enacted Chapter 31380, Chapter 31389, Chapter

31390, and Chapter 31391, Acts of 1956. The first of this

series of acts became effective July 26, 1956, and the other

three became effective August 1, 1956. These acts, includ

ing those they amended, defined a complete scheme to

administer the public school system. They were enacted

under the police powers to promote the safety, health, order,

welfare and education of the people within the State of

Florida.

They also confer additional powers on the governor in

that they authorize him to promulgate and enforce rules

and regulations to protect the public against violence and

property damages. They recognize that the state has the

dominant interest in and is the natural guardian of the

public against violence. It is perfectly evident that these

acts had in view recent Federal decisions affecting segrega

tion in that they authorized county boards of public in

struction to choose personnel from all available sources, to

consolidate school programs at any school center and to

dismiss any teacher or teachers not essential to carry on

the consolidated school program.

Another purpose of these acts was to preserve the wel

fare of all classes and by a system of uniform tests classify

all school entrants according to intellectual ability and

scholastic proficiency to the end that there will be estab

lished in each school within the county an environment of

23

equality among those of like qualification and academic

attainments. What effect, if any, the system so created will

have on the case before us, I do not discuss. The point is

that it expresses the public policy of the state as to the

question. Those administering our educational program

are moving as fast as consistent with wise judgment to set

it up and other systems not materially different to protect

the public from violence have been approved though thej'-

had little, if any, educational aspect, United A. A. & A. I. W.

vs. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, — U. S. — ,

100 L. Ed. (Advance p. 666); Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. 8.

78, 72 L. Ed. 172.

These acts were passed since we last considered this

case, they offer a sound and sensible basis to handle the

school problem in Florida which was thrown into confusion

overnight by Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, 347

U. 8. 483, 68 L. Ed. 873, which in turn overthrew and kicked

out the window the recognized school policy approved by

all courts in the country for generations. The change has

precipitated school problems peculiar to every state in the

country. If Florida is not authorized to meet and solve

the problem by which it is confronted in a sane and sensible

manner, then all the law I have been taught governing state

and Federal power has been pitched down the drain.

For these reasons I concur in the opinion of Mr. Justice

Roberts.

H obson , J Concurring specially:

I concur in the conclusion reached by the majority be

cause the testimony which was taken at the direction of this

court by the Honorable John A. H. Murphree, and which is

now before us for consideration, was not in the record when

the Supreme Court of the United States said “ there is no

reason for delay” . This testimony, as well as the revealing

incidents (of which we may take judicial notice) which have

24

occurred since the repudiation of the ‘ ‘ separate but equal ’ ’

doctrine, convinces me that the immediate admission of

relator to the University of Florida College of Law would

result in great public mischief.

In the interest of both races, that is to say, the common

weal, the writ, of mandamus should, in the exercise of

sound judicial discretion, be withheld until the Supreme

Court of the United States in this case, after consideration

of those matters which it has not heretofore had an oppor

tunity to weigh and evaluate, unequivocally directs that

relator be admitted to the College of Law at the University

of Florida. In such event the onus will rest, as it should,

with the tribunal responsible for the initial departure from

a constitutional interpretation which had served us for so

many years. And since I am bound by the paramount

federal law, if such ruling should be made by a fully in

formed Supreme Court, I could not fail to comply without

stultifying my oath of office.

T hom as , J. Dissenting:

After a careful examination of the opinion prepared

for a majority of the court, I come to the conclusion that

I must dissent.

It seems fitting, before recording* my reasons for dis

agreement, to set out a chronology of the important steps

in this protracted litigation.

On 30' May 1949 the relator filed in this court a petition

for a writ of mandamus to command the respondents,

members of the Board of Control and the president and.

the registrar of the University of Florida, to admit the

petitioner, a Negro, to the college of law of the University.

Adams, C. J., and Terrell, Sebring, Barns and Hobson, J.J.,

voted to issue an alternative writ of mandamus while

Chapman, J., and the writer dissented on the ground that

the petitioner had not first applied to the State Board of

Education. The alternative writ, issued1 10 June 1949,

was in the usual form and! commanded the respondents to

admit the relator to the college of law or show cause 11

July 1949 why a peremptory writ should not follow.

From the answers, filed in response to the alternative

writ of mandamus, it appeared that at the time of relator ’s

application the college of law at the University of Florida

was the only law school maintained in the state by taxes,

and that relator had been informed that because there was

no law school then functioning within the State where Negro

students could be enrolled, the Board of Control was pre

pared to provide him, at a college or university acceptable

to him in another state, courses of study as valuable as

any offered in an institution of higher learning in Florida.

At this time and for many years before the Florida Agri

cultural and Mechanical College staffed exclusively by

Negroes and maintained exclusively for members of the

Negro race, supported by State taxation, had been function

ing in Tallahassee.

Attention was drawn to the laws of the state restricting

courses at the University of Florida to members of the

white race and the respondents asserted that in denying

the relator’s application they had not acted arbitrarily but

had only obeyed the statute and the Constitution. It was

provided in Section 228.09, Florida Statutes, that “ schools

for white children and the schools for negro children shall

be conducted' separately.” Section 12 of Art. XII, of the

Consitution follows: “ White and colored children, shall

not be taught in the same school, but impartial provision

shall be made for both.”

To repeat, it was in obedience to the statutory and con

stitutional inhibitions that the respondents declined to ad

mit the relator to the college' of law at the University of

Florida, and in order to afford him the training he desired

they offered to secure him an education of equal quality

at an institution outside the state where Negroes were not

barred.

It was further represented that all state institutions

of higher learning, including the University of Florida,

and Florida Agricultural and. Mechanical College— the

name was changed to Florida Agricultural and Mechanical

University by Chapter 27995, Laws of Florida, Acts of

1953—were managed and controlled, by the Board of Con

trol under the supervision of the State Board of Education

and that from time to time, as the need arose, courses were

added to the curricula of the institutions. Carrying out

this policy, according to the answer, the Board of Control

had, prior to the demand of relator, included in its budget

requests for funds to be used in the establishment of a

law school at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College.

As a conclusion the respondents stated that if the relator

still refused ‘ ‘ to accept out-of-state scholarship or other pro

vision which may be made for his instruction in the courses

he has requested, elsewhere than at a State institution

established for white students exclusively, and it should be

held that said arrangement is insufficient to satisfy the

relator’s lawful demands, the respondent, Board of Con

trol, has made provision for relator’s immediate admission

and enrollment” at the law school established at Florida

Agricultural and Mechanical College. In the event the-

“ necessary fanilities, equipment and personnel for said

course of study should not be immediately available” at

Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College, continued

respondents, the respondents had “ made provision for

[relator’s] instruction # # * at the only other institution

of higher learning in the State of Florida offering such

course, until such time as adequate and comparable facili

ties and personnel * * * [could] be obtained and physi

cally set up at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College

for Negroes, in Tallahassee, Florida.”

The relator moved for a peremptory writ notwithstand

ing the answer.

The members of this court were in unanimous agree

ment that the entry of a final order should be withheld,

27

and jurisdiction meanwhile retained, until the court should

be satisfied either that the Board of Control had furnished,

or failed to furnish, to the relator the opportunity, to

pursue his desired course of study, substantially equal to

the opportunity given students at other institutions sup

ported by taxation. State ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of

Control of Florida et al., Fla., 47 So. 2d 608.

The relator moved again for a peremptory writ, 16 May

1951. State ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control et al.,

Fla., 53 So. 2d 116. This writ was denied, 15 June 1951,

on the ground that the relator had not shown that he had

exhausted all reasonable means of gaining admittance to

the University of Florida. The order was entered without

prejudice to the right to renew the motion for a peremptory

writ when the relator could show that he had “ brought

himself within the principles enunciated in State ex rel.

Hawkins v. Board of Control # * Fla., 47 So. 2d 608.

The relator petitioned the Supreme Court of the United

States to review the last order by certiorari but on 13

November 1951, that court declined because the judgment

was not final. Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control

of Florida, 342 U. S. 877, 72 S. Ct. 166, 96 L. Ed. 659.

On 7 June 1952 the relator presented his third motion

for a peremptory writ. In an opinion of this court filed

1 August 1952, it was written that by making this motion

the relator was taking the position that he would only

enjoy the full political rights guaranteed by the Federal

Constitution by being admitted to the University of Florida

Law School, a school maintained exclusively for white per

sons, even though a law school, exclusively for Negroes,

supported by taxation was available to him. The court

held, unanimously, that the motion should be denied and the

alternative writ quashed. State ex rel. Hawkins v. Board

of Control et al., Fla., 60 So. 2d 162.

The Supreme Court of the United States granted cer

tiorari to review this judgment, ordered the judgment

vacated and remanded the cause to this court “ for consid

28

eration in the light of the Segregation Cases decided May

17, 1954, Brown v. Board of Education, etc., and conditions

that now prevail.” The mandate was dated 24 May 1954.

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control of Florida,

347 U. S. 971, 74 S. Ct. 783, 98 L. Ed. 1112.

It should be remarked here that the case of Brown v.

Board of Education, cited in the mandate, was one dealing

with elementary schools while the present litigation involved

a graduate school, and the direction that this court recon

sider its judgment not only in the light of the cited case

but also of “conditions that now prevail” was quite con

fusing as will be emphasized when we advert to the de

cision in Brown v. Board of Education and allied decisions

of the Supreme Court of the United States, and to a later

mandate affecting the present litigation. (Italics supplied.)

In response to the mandate, this court entered its order

31, July 1954, directing the relator to amend his petition

within 60 days so as to present the issues raised by the

original petition “ ‘in the light of the Segregation Cases

* * * and conditions that now prevail’ ” and directing re

spondents within 30 days afterward to amend their return

so that this court would be enabled to abide by the man

date.

In obedience to the order both petition and return were

amended resulting in presentation of the single question

“ whether or not the relator [was] entitled to be admitted

to the University of Florida Law School upon showing that

he [had] met the routine entrance requirements.” State

of Florida, ex rel. Virgil D. Hawkins, Relator v. Board of

Control, Fla., 83 So. 2d 20. This opinion was filed 19 Oc

tober 1955. So the issue was then narrowed to the one

whether or not the relator’s petition should be rejected

because he was a member of the Negro race.

Meanwhile, between the time the pleadings were

amended and the last cited decision was rendered, the Su

preme Court of the United States entered its opinion,

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294, 75

S. Ct. 753, implementing the decision in the case of Brown

29

v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct.

686, 98 L. Ed. 873, 38 A. L. R. 2d 1180. In the ‘implemen

tation decision’ that court recognized that varied problems

would exist locally the solution of which might require

time and that school authorities should bear the burden of

showing what delay was necessary “ in the public interest

and # * consistent with good faith compliance at the

earliest practicable date.” Brown v. Board of Education

of Topeka, 349 U. 8. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753.

So when the opinion of 19 October 1955 was filed by

this court it was the majority view that, inasmuch as the

mandate had referred to a case dealing with elementary

schools, and the decision in that case had been implemented

to permit some delay in meeting and solving problems, and

this court had been directed to re-examine the decision in the

present case in the light not only of that case but also in the

light of “ conditions that now prevail,” a commissioner

should be appointed to take testimony about local problems,

and adjustments that would be necessary under conditions

that prevailed, in order to admit the relator, and that upon

such testimony the court would decide when a peremptory

writ should issue. Four months from the date of the deci

sion, 19 October 1955, was the period fixed for taking the

testimony, and before that time expired the period was

extended to 31 May 1956.

A petition for certiorari to review the decision of 19

October 1955 was presented to the Supreme Court of the

United States and that court, 12 March 1956, while the

testimony being taken under the decision of 19 October 1955

was incomplete, entered a decision per curiam. Some con

fusion resulted because the order began with the statement

“ The petition for certiorari is denied” and the concluding

paragraph began with the statement “ The petition for

writ of certiorari is granted. ’ ’ The issuance of the mandate

of 24 May 1954 was recited, then the court observed that it

directed “ the case be reconsidered in light of our decision

30

in the Segregation Cases,” but any reference to considera

tion of the matter ‘ ‘ in the light of * # * conditions that now

prevail” was omitted. Then the court explained that in

directing this court to reconsider there was no implication

that decrees affecting graduate students present the “ prob

lems of public elementary and secondary schools.” To

stress the point it was announced that in three cases: Sweatt

v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the

University of Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631, Cf. McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, 339 U. S.

637, the court had “ ordered the admission of Negro appli

cants to graduate schools without discrimination because

of color” and it was expressly stated that the ‘implementa

tion decision’ “had no application to a case involving a,

Negro applying for admission to a state law school.” (Ital

ics supplied.)

So the mandate of 24 May 1954 was recalled and the

case remanded, ‘ ‘ on the authority of the Segregation Cases

decided May 17, 1954, Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483.” This is the now familiar decision dealing with

elementary schools. The judgment concluded with this

significant language: ‘ ‘ As this case involves the admission

of a Negro to a graduate professional school, there is no

reason for delay. He is entitled to prompt admission under

the rules and regulations applicable to other qualified can

didates.” State of Florida ex rel. Virgil D. Hawkins v.

The Board of Control, opinion filed March 12, 1956.

Despite the ambiguities which I have pointed out, I

think, and I thought as early as 19 October 1955, when the

decision of this court directing the taking of testimony was

rendered, that the Supreme Court of the United States

had, in effect, declared invalid the provision of the Consti

tution of the State of Florida in conflict with the interpreta

tion that court had given the Constitution of the United

States.

From the time of the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 IT. S. 537, 16 S. Ct. 1138, 41 L. Ed. 256, rendered in

1896, decisions by this court that white and colored students

31

should be segregated but that the opportunities should be

equal enabled members of this court to observe their per

sonal oaths to support, protect and defend the Constitution

of this state and do so in perfect harmony with rulings of

the Supreme Court of the United States on the subject.

The inhibition in the State Constitution is stated in clear,

unambiguous language. Construing it verbatim brought no

inconsistency with construction of the Constitution of the

United States which contains no express language prohibit

ing segregation. In the recent decision overturning a prece

dent of 60 years, nobody seems ever to have bothered to

consider the effect upon the oath of members of this court

to support an absolute state constitutional inhibition of

integration in schools in this state.

At the time of the rendition of the decision of 19 October

1955 I thought, despite the apparent ambiguity in the order

on the first petition of certiorari, that no further testimony

with reference to prevailing conditions had been contem

plated. Because of this view and the thought that no testi

mony was needed to dispose of the case, the issue having

been reduced to the one whether a Negro could be barred

simply by reason of his race, I thought the decision was

wrong, so I dissented. And my conviction was buttressed

by the understanding that the respondents had not re

quested the procedure, anyway.

My conclusion was confirmed by the entry of the second

judgment. Even though there was a repeated reference

to the Brown case, the language already quoted and then

repeated dissipated any impression that there was occasion

for further delay.

I cannot agree that when a decision denying a petition

for mandamus is, in effect, reversed, the subordinate court

retains the power to issue the writ at some later date. It is

my view that in such case the discretion, held to have been

abused, has been exhausted and the time has arrived to

obey the mandate of the higher court.

It seems to me that if this court expects obedience to

its mandates, it must he prepared immediately to obey

32

mandates from a higher court. In this case when the Fed

eral question was presented and determined by the Su

preme Court of the United States, the ruling became bind

ing upon this court at once regardless of our lack of

sympathy with the holding.

Inasmuch as, to repeat, the Supreme Court of the

United States has ruled that “ there is no reason for delay”

and that the ‘ ‘ relator is entitled to prompt admission under

the rules and regulations applicable to other qualified can

didates” I think this litigation has ended and that the

matter is now one purely of administration.

.Dr ew , J., Dissenting:

It is a fundamental truth that justice delayed is justice

denied. This case has now reached the point where further

delay will be tantamount to a denial of a constitutional

right of relator.

Mr. Justice Sebring pointed out the course in his dis

senting opinion in State ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control,

83 So. 2d 20 (Fla. 1955) with which I must now agree.

The Constitution of the United States of America, Article

VI, provides that, “ This Constitution * * # shall be the

supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State

shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or

Laws of Any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” The

oath of office I have taken requires that I “ support, protect

and defend” it. The Supreme Court of the United States

has been established by long tradition as the final interpreter

of the Constitution of the United States. Such an interpreta

tion has been made in this case.

I cannot conclude that- any discretion remains in this

Court to lawfully postpone the issuance of a peremptory

writ. This mandamus is a discretionary writ is academic,

but that this broad principle is applicable in those cases

where an authoritatively declared constitutional right is

being denied—I cannot agree. See State ex rel. Beacham

33

v. Wynn, 158 Fla. 182, 28 So. 2d 253, 254 (1946), in which

this Court said “ Where the right is indisputable there is

no room for the exercise of discretion other than in keep

ing with the law.” Also see Osborn v. The Bank of the

United States, 22 U. S. 738, 866, 6 Law Ed. 204, 234 (1824).

Courts are the mere instruments of the law and can

will nothing. Judicial discretion is a legal discretion. It

is a discretion to be exercised in discerning the course

prescribed by law. When, as here, that course has been

discerned and a determination has been reached that relator

is being denied his constitutional right, it is the clear duty

of this Court to enforce the right. The power vested in

the judiciary should never be exercised for the sole pur

pose of giving effect to the will of the judge. The power we

possess is for the purpose of giving effect to the will of

the law. I conceive it to be my plain duly to give effect

to the law which has been established by the United States

Supreme Court.

I, therefore, respectfully dissent.

S u pr em e P r in t in g C o., I n c ., 114 W orth S treet, N . Y . 13, B E e k m a n 3 -2320

*^§!!^d49