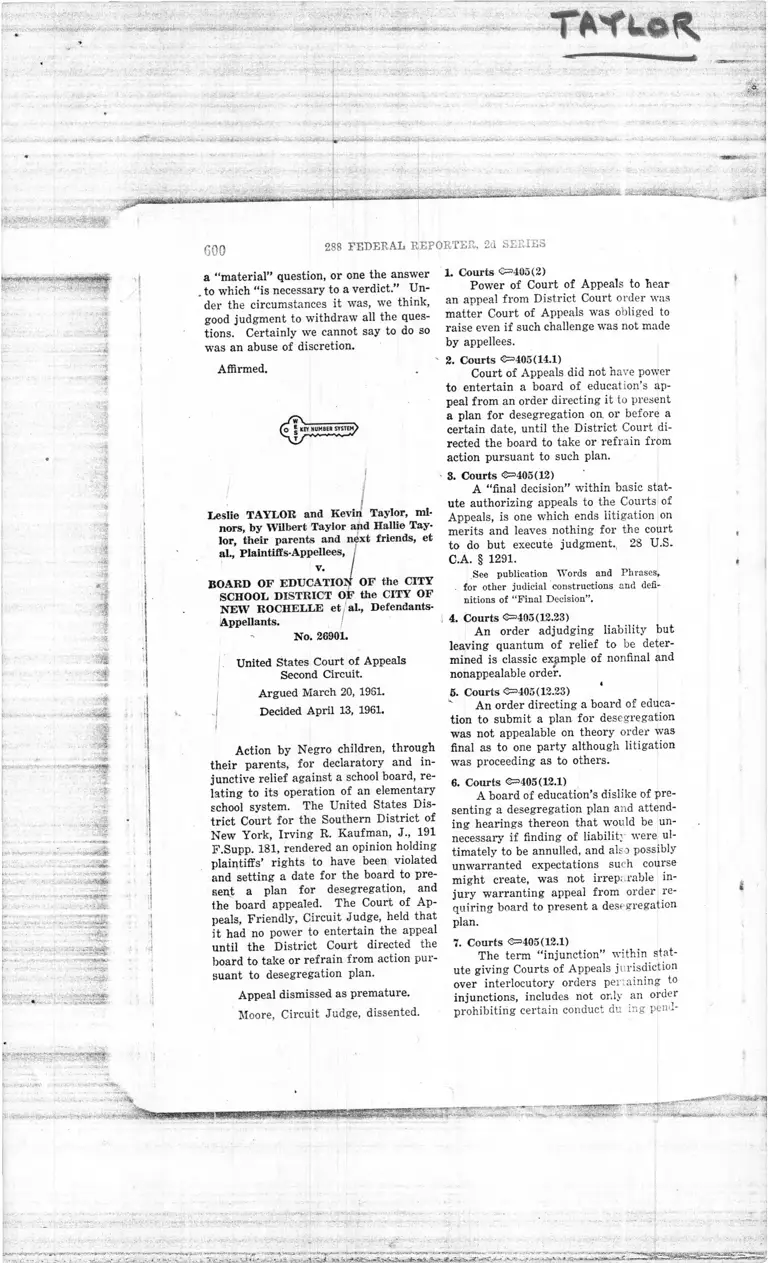

Taylor v. New Rochelle Board of Education Court Opinion

Unannotated Secondary Research

April 13, 1961

8 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Taylor v. New Rochelle Board of Education Court Opinion, 1961. 18f5e1b1-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/881a0496-5b90-4249-b29c-e2aa2da025b7/taylor-v-new-rochelle-board-of-education-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

- H

- .

"4 * >?»• *» ir A-ifcji *i * w ■■<? j .*< £$« £ -«•<*.» ,-t , v & « s?

..v:.j t'mr.mm, . .::.., . - ̂ - - - - -

GOO 288 F E D E R A L REPORTER,

a “ material” question, or one the answer

to which “ is necessary to a verdict.” Un

der the circumstances it was, we think,

good judgment to withdraw all the ques

tions. Certainly we cannot say to do so

was an abuse of discretion.

Affirmed.

(o | KEY NUMBER SYSTEM^

1. Courts 0=405(2)

Power of Court of Appeals to hear

an appeal from District Court order was

matter Court of Appeals was obliged to

raise even if such challenge was not made

by appellees.

2. Courts 0=405(14.1)

Court of Appeals did not have power

to entertain a board of education’s ap

peal from an order directing it to present

a plan for desegregation on. or before a

certain date, until the District Court di

rected the board to take or refrain from

action pursuant to such plan.

:7

Leslie TAYLOR and Kevin Taylor, mi

nors, by Wilbert Taylor and Hallie Tay

lor, their parents and next friends, et

al., Plaintiffs-Appellees,

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF the CITY

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF the CITY OF

NEW ROCHELLE et al., Defendants-

Appellants.

- No. 26901.

United States Court of Appeals

Second Circuit.

Argued March 20, 1961.

Decided April 13, 1961.

Appeal dismissed as premature.

Moore, Circuit Judge, dissented.

3. Courts €=405(12)

A “ final decision” within basic stat

ute authorizing appeals to the Courts of

Appeals, is one which ends litigation on

merits and leaves nothing for the court

to do but execute judgment, 28 U.S.

C.A. § 1291.

See publication Words and Phrases,

- for other judicial constructions and defi

nitions of “ Final Decision” .

Action by Negro children, through

their parents, for declaratory and in

junctive relief against a school board, re

lating to its operation of an elementary

school system. The United States Dis

trict Court for the Southern District of

New York, Irving R. Kaufman, J„ 191

F.Supp. 181, rendered an opinion holding

plaintiffs’ rights to have been violated

and setting a date for the board to pre

sent a plan for desegregation, and

the board appealed. The Court of Ap

peals, Friendly, Circuit Judge, held that

it had no power to entertain the appeal

until the District Court directed the

board to take or refrain from action pur

suant to desegregation plan.

4. Courts €=405(12.23)

An order adjudging liability but

leaving quantum of relief to be deter

mined is classic example of nonfinal and #

nonappealable order.

5. Courts <3=405(12.23)

' An order directing a board of educa

tion to submit a plan for desegregation

was not appealable on theory order was

final as to one party although litigation

was proceeding as to others.

6. Courts €=405(12.1)

A board of education’s dislike of pre

senting a desegregation plan and attend

ing hearings thereon that would be un

necessary if finding of liability were ul

timately to be annulled, and also possibly

unwarranted expectations such course

might create, was not irreparable in

jury warranting appeal from order re

quiring board to present a desegregation

plan.

7. Courts €=405(12.1)

The term “ injunction” within stat

ute giving Courts of Appeals jurisdiction

over interlocutory orders pertaining to

injunctions, includes not only an order

prohibiting certain conduct du mg pend-

'

••• .vm»—’■ ■■ • ■'*+*-* -Tj

ofr***** ^ , . . .*•• ; ,

• -ft l « '* y s -s - --. . ~ >, V '5*» t ; »',■■•);» «= V ss> . -S J -!■« 4 j-v .'- i / if/y ’v-'

TAYLOR v. BOARD (

Cite as -S S 1

•encv of litigation, but also one that com

mands it. 28 U.S.C.A. § 1292(a) (1).

See publication Words and Phrases,

for other judicial constructions and defi

nitions of “ Injunction”.

8. Injunction ©=5

A judicial command that relates

merely to taking of a step in a judicial

proceeding is not generally regarded as

a mandatory injunction.

9. Courts <3=405(12.1)

Not every order containing words of

restraint is a negative injunction within

statute authorizing appeals from certain

injunctive orders, and not every order

containing words of command is a man

datory injunction within that section.

28 U.S.C.A. § 1292(a) (1).

10. Courts ©=405(12.1)

An order directing a board of educa

tion to submit a desegregation plan on

or before a certain date was not appeal

able under interlocutory appeals statute

as an order granting a mandatory in

junction. 28 U.S.C.A. § 1292(a) (1).

Thurgood Marshall, New York City

(Paul B. Zuber, Constance Baker Motley

and Jack Greenberg, New York City, on

the brief), for plaintiffs-appellees. .

Murray C. Fuerst, New Rochelle, N. Y.

(Julius Weiss, New York City, on the

brief), for defendants-appellants.

Before MOORE, FRIENDLY and

SMITH, Circuit Judges.

FRIENDLY, Circuit Judge.

In this action, eleven Negro children,

proceeding through their parents, seek

)F EDUCATION, ETC. 601

r,2d U0O (I'JOl)

declaratory and injunctive relief against

the Board of Education of New Rochelle,

New York, and the Superintendent of

Schools. On January 24, 1961, Judge

Kaufman signed an opinion, 191 F.Supp.

181, stated to constitute the District

Court’s findings of fact and conclusions

of law, which held that various acts of

the defendants violated plaintiffs’ con

stitutional rights as defined in Brown v.

Board of Education, 1954, 347 U.S. 483,

74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed. 873, and later de

cisions of the Supreme Court. The opin

ion ended with two paragraphs, quoted

in the margin,1 in which the District

Judge stated, among other things, that

he deemed it “ unnecessary at this time

to determine the extent to which each of

the items of the relief requested by plain

tiffs will be afforded,” [191 F.Supp. 198]

but would defer such determination until

the Board had presented, on or before

April 14, 1961, “ a plan for desegregation

in accordance with this Opinion, said de

segregation to begin no later than the

start of the 1961-62 school year.”

[1, 2] Pursuant to authorization by a

5-3 vote at a meeting of the Board of

February 7, 1961, defendants appealed to

this Court on February 20, 1961. On

March 7, 1961, the District Judge denied

an application by them to extend the

date for filing a plan pending determina

tion of the appeal, as well as a motion by

plaintiffs for an order directing defend

ants immediately to assign plaintiffs to

elementary schools other than the Lincoln

' School. Thereupon, defendants moved

this Court for a stay of the direction to

file a plan, pending the appeal. At the

hearing on that motion, the Court ques-

I. “The Decree

“ In determining the manner in which

the Negro children residing within the

Lincoln district are to be afforded the op-

opportunities guaranteed by the Constitu

tion, I will follow the procedure author

ized by the Supreme Court in Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 [75 S.

Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1083] (1955), and

utilized by many district courts in im

plementing the Brown principles. Thus,

I deem it unnecessary at this time to

determine the extent to which each of

the items of relief requested by plaintiffs

28S F .2d— 38V2

will be afforded. Instead, the Board is

hereby ordered to present to this Court,

on or before April 14, 1901, a plan for

desegregation in accordance with this

Opinion, said desegregation to begin no

later than the start of the 1961-02 school

year. This court will retain jurisdiction

of this action until such plan has been

presented, approved by the court, and

then implemented.

“The foregoing Opinion will constitute

the court’s findings of fact and conclu

sions of law.”

' ■ ’ ..... . - - . - -I.-,- —», . ~ ' - . --. ■ , .... . V ' - ....1 ........ ■■ ■ -

A\: L.' ■■' .—-e- V-*' . - c-„ ,m - h ■■ ■ ■

' . —..of r A"'

•,:... < i:p > fi&H&a -;<h

- - i^ M

602 288 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

tioned whether the appeal had not been

prematurely taken and was not, there

fore, beyond the appellate jurisdiction

conferred upon the Court by Congress.

Later we directed the filing of briefs on

this issue and extended the Board’s time

to file the plan pending the Court’s de

cision on the question of jurisdiction and

in any event to May 3, 1961. Appellees

now challenge our power to hear an ap

peal at this stage, but the question is

one this Court was obliged to raise in

any event, Mitchell v. Maurer, 1934, 293

U.S. 237, 244, 55 S.Ct. 162, 79 L.Ed. 338,

and it is better that this be determined

, now rather than after further time has

elapsed. Upon full consideration, we

conclude that we have no power to en

tertain the Board’s appeal until the Dis

trict Court has finished its work by di

recting the Board to take or refrain

from action. /

Familiar decisions of the) Supreme

Court establish the controlling principles.

“ Finality as a condition of review is an

historic characteristic of federal appel

late procedure. It was written into the

first Judiciary Act and has been departed

from only when observance of it would

practically defeat the right to any review

at all." Cobbledick v. United States,

1940, 309 U.S. 323, 324-325, 60 S.Ct.

540, 541, 84 L.Ed. 783. “ The foundation

of this policy is not in merely technical

conceptions of ‘finality.’ It is one against

piecemeal litigation. ‘The case is not to

be sent up in fragments * * * ’ Lux-

ton v. North River Bridge Co., 147 U.S.

337, 341 [13 S.Ct. 356, 358, 37 L.Ed.

194]. Reasons other than conservation

of judicial energy sustain the limitation.

One is elimination of delays caused by

interlocutorv appeals.’’ Catlin v. United

States, 1945, 324 U.S. 229, 233-234,

65 S.Ct. 631, 634, 89 L.Ed. 911.

[3 ,4 ] A “ final decision” within 28

U.S.C. § 1291, the basic statute authoriz

ing appeals to the courts of appeals, and

its predecessors going back to §§ 21 and

22 of the Act of Sept. 24, 1789, c. 20, 1

Stat, 73, 83-84, “ is one which ends the

litigation on the merits and leaves noth

ing for the court to do but execute the

judgment.” Catlin V. United States,

supra, 324 U.S. at page 233, 65 S.Ct. at

page 633. Plainly Judge Kaufman’s de

cision of January 24, 1961 does not fit

that description. It constituted only a

determination that plaintiffs were en

titled to relief, the nature and extent of

which would be the subject of subsequent

judicial consideration by him. What re

mained to be done was far more than

those ministerial duties the pendency of

which is not fatal to finality and conse

quent appealability, Ray v. Law, 1805,

3 Cranch 179, 180, 2 L.Ed. 404. An

order adjudging liability but leaving the

quantum of relief still to be determined

has been a classic example of non-finality

and non-appealability from the time of

Chief Justice Marshall to our own, The

Palmyra, 1825, 10 Wheat. 502, 6 L.Ed.

375; Barnard v. Gibson, 1849, 7 How.

650, 12 L.Ed. 857; Leonidakis v. Inter

national Telecoin Corp., 2 Cir., 1953, 208

F.2d 934; 6 Moore, Federal Practice

(1953 ed.), p. 125 and fn. 5, although in

all such cases, as here, this subjects the

defendant to further proceedings in the

court of first instance that will have been

uncalled for if that court’s determination

of liability is ultimately found to be

wrong. Recognizing that this may create

hardship, Congress has removed two

types of cases from the general rule that

appeals may not be taken from decisions

that establish liability without decreeing

a remedy— namely, decrees “ determining

the rights and liabilities of the parties to

admiralty cases in which appeals from

final decrees are allowed,” 28 U.S.C. §

1292(a) (3), added by the Act of April 3,

1926, c. 102, 44 Stat. 233, and “ judgments

in civil actions for patent infringement

which are final except for accounting .

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a) (4), added by the

Act of Feb 28, 1927, c. 228, 44 Stat.

1261. Congress’ specification of these

exceptions, manifestly inapplicable here,

underscores the general rule.

This salutary Federal rule requiring

finality as a condition of appealability

has become subject, over the year . to

exceptions other than those just men

tioned, some fashioned by the com —

ot

31

ti

P

X

n

d.

tl

ei

w

R

F

I.

tl

P

si

ii

a

ii

P

r.

ti

r

ti

h

ti

H

5

ii

e

t

<QK.

g

t

g

c

s

u

5

u

v

i

t

i

r,

l

c

TAYLOR v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, E1]

Cite as 288 F.2d 600 (1061)

!C.

others enacted by Congress. The instant

appeal does not come within any,

[5,6] Of the judicially created excep

tions, the one referred to in Dickinson v.

Petroleum Conversion Corporation, 1950,

338 U.S. 507, 70 S.Ct. 322, 94 L.Ed. 299,

namely, that under some circumstances a

decree may be final as to one party al

though the litigation proceeds as to oth

ers, is so manifestly inapplicable that we

would not mention it if appellants had

not. Similarly inapplicable is the rule in

Forgay v. Conrad, 1848, 6 How. 201, 12

L.Ed. 404, that a judgment directing a

defendant to make immediate delivery of

property to a plaintiff is appealable de

spite a further provision for an account

ing. The scope of this doctrine is narrow

and rests upon “ the potential factor of

irreparable injury,” 6 Moore, Federal

Practice (1953 ed.), p. 129—just how

narrow is shown by decisions refusing

to apply it to a decree that adjudged

rights in property but made no disposi

tion of the property pending a further

hearing relating to its precise identifica

tion, Rexford v. Brunswick-Balke-Col-

lender Co., 1913, 228 U.S. 339, 33 S.Ct.

515, 57 L.Ed. 864, or to a decree award

ing possession to the United States under

eminent domain but reserving the ques

tion of compensation, Catlin v. United

States, supra, 324 U.S. at page 232, 65

S.Ct. at page 633, overruling our con

trary decision in United States v. 243.22

Acres of Land, 2 Cir., 1942,129 F.2d 678.

See Republic Natural Gas Co. v. State of

Oklahoma, 1948, 334 U.S. 62, 68 S.Ct.

972, 92 L.Ed. 1212. Here, while we

J i f it o M ^ e fe n d a n ts

at' woutcHoetending hearings thereon

w m m m

were ultimately to be annulled

the DoIsihlY um ^ dVI'Wr*»J»eRniWB

may create/ this is scardety

injury a t .

not an irre y map-

rirtem Cohen v. Benefi

cial Industrial Loan Corp., 1949, 337 U.S.

541, 545-547, 69 S.Ct. 1221, 1225, 93 L.

Ed. 1528, also advanced by appellants,

permitting review of orders “ which final

ly determine claims of right separable

from, and collateral to, rights asserted in

the action, too important to be denied re

view and too independent of the cause it

self to require that appellate considera

tion be deferred until the whole case is

adjudicated.” Here the issue sought to

be reviewed, far from being collateral to

the main litigation, represents the very

findings and conclusions upon which any

final judgment against the defendants

must rest.

[7] Turning to statutory exceptions,

the only one that could be, and is, claimed

to be applicable is 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)

(1). That gives us jurisdiction over

“ Interlocutory orders of the district

courts * * * granting, continuing,

modifying, refusing or dissolving injunc

tions, or refusing to dissolve or modify

injunctions, except where a direct review

may be had in the Supreme Court.” The

term “ injunction” includes not only an

order prohibiting certain conduct during

the pendency of litigation but also one

that commands it. Societe Interna

tionale, etc. v. McGrath, 1950, 86 U.S.

App.D.C. 157, 180 F.2d 406.

Appellants contend Judge Kaufman’s

decision granted both a prohibitory and

a mandatory injunction. They say the

order “ in effect” prohibited them from

proceeding with their plans to recon

struct the Lincoln School and commanded

them to submit a plan. If the former

were so, the order would clearly be ap

pealable; we have searched the opinion

for substantiation but in vain. To be

sure, the opinion says the proposed re

construction alone might aggravate the

problem rather than ameliorate it; and

we fully appreciate why the Board may

hesitate to proceed in the light of this,

as, indeed, it might have if the opinion

had not yet been rendered. But as yet

we can only conjecture whether the Dis

trict Court will enjoin the rebuilding or

permit this if accompanied by other acts;

and a defendant’s apprehension that con

duct on his part may ultimately be re

strained is not an “ injunction” within §

1292(a) (1).

/ 1 „ '.-•-•-i;^ ;^^.r^ ..,s i.'/^r# ---*«-v'ri-^- - w v v v ^ M t ^ & r - y ' ' ' . - sso f̂e

*. i, -r.'̂ -fc, -:

f -1 - fi'i'vr -tiiiaiaYi,t.-

288 F E D E R A L R E P O R T E R , 2d S E R IE S60 i

[8, 9] Whether Judge Kaufman’s di

rection for the submission of a plan on

April 14 is a mandatory injunction re

quires, in the first instance, interpreta

tion of what was said. It is common

practice for an equity judge first to reach

a conclusion as to liability and to deter

mine the appropriate relief later in the

event of an affirmative finding. If the

District Judge had said in his opinion

only that a further hearing would be held

at which the parties would have an op

portunity to express themselves as to re

lief, by testimony, argument, or both, it

would be entirely plain that he had not

granted a mandatory injunction, and this

would be so even if he had also stated

that, in the interest of orderly procedure,

he would expect the defendants to take

the lead at the hearing. In substance

this is what Judge Kaufman did.. Al

though the penultimate paragraph pf his

opinion is headed “ The Decree,” the con

text makes clear that the few sentences

that follow were not, themselves/ decre

tal, but simply explained how he planned

to fashion his decree. To be sure, the

opinion used the word “ ordered” with re

spect to the filing of a plan, just as courts

often “ order” or “ direct” parties to file

briefs, findings and other papers. Nor

mally this does not mean that the court

will hold in contempt a party that does

not do this, but rather that if he fails to

file by the date specified, the court may

refuse to receive his submission later

and may proceed without it. That this

was what Judge Kaufman intended is

confirmed by his later opinion denying an

extension of the April 14 date, in which

he spoke of having “ specifically requested

the Board to submit its plan for desegre

gation of the Lincoln School” and of hav

ing given the Board “ an opportunity to

submit” such a plan. Moreover, even if

2. For clarity we note what ought he ob

vious, namely, that the Board s submis

sion of a plan of desegregation implies no

acceptance of the District Judge's deter

minations of fact and law and no waiver

of a right to appeal— any more than does

the action of a losing party in any suit,

either at the request of the court or of

the order was intended to carry contempt

sanctions, which we do not believe, a

command that relates merely to the tak

ing of a step in a judicial proceeding is

not generally regarded as a mandatory

injunction, even when its effect on the

outcome is far greater than here, 6

Moore, Federal Practice (1953 ed.) pp.

4G-47.2 For just as not every order con

taining words of restraint is a negative

injunction within 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)

(1), Baltimore Contractors, Inc. v. Bod-

inger, 1955, 348 U.S. 176, 75 S.Ct. 249,

99 L.Ed. 233; Fleischer v. Phillips, 2

Cir., 1959, 264 F.2d 515, 516, certiorari

denied 1959, 359 U.S. 1002, 79 S.Ct. 1139,

3 L.Ed.2d 1030; Grant v. United States,

2 Cir., 1960, 282 F.2d 165, 170, so not

every order containing words of com

mand is a mandatory injunction within

that section.

[10] Our review of the cases that

have reached appellate courts in the wake

of Brown v. Board of Education, supra,

and its supplement, 1955, 349 U.S. 294,

75 S.Ct. 753, has revealed only one in

which jurisdiction may have been taken

under such circumstances as here. In

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hills

boro, 6 Cir., 1956, 228 F.2d 853; Brown

v. Rippy, 5 Cir., 1956, 233 F.2d 796;

Booker v. State of Tennessee Board of

Education, 6 Cir., 1957, 240 F.2d 689,

and Holland v. Board of Public Instruc

tion, 5 Cir., 1958, 258 F.2d 730, the ap

peals were from final orders denying in

junctive relief. In Aaron v. Cooper, 8

Cir., 1957, 243 F.2d 361, an injunction

was denied because of a voluntary plan

offered by the Little Rock School District

which the District Court found satis

factory, but jurisdiction was retained;

since the order denied an injunction is

was therefore appealable whether it was

deemed final or interlocutory.3 In Boarc

his own volition, in submitting a form of

judgment conforming with findings and

conclusions from which he dissents.

3. Later cases involving the Little Rock

situation, Thomason v. Cooper, 8 Cir.,

3958, 254 F.2d S08; Aaron v. Cooper,

8 Cir., 1958, 257 F.2d S3, affirmed

Cooper v. Aaron, 195S, 358 U.S. 1, ‘ 8

TAYLOR v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, ETC.

Cite as 288 F.2d COO (1961)

605

of Supervisors of L. S, U., etc. v. Dudley,

5 Cir., 1958, 252 F.2d 372, certiorari de

nied, 1958, 358 U.S. 819, 79 S.Ct. 31, 3

L.Ed.2d 61; Board of Supervisors of L.

S. U., etc. v. Wilson, 1951, 340 U.S. 909,

71 S.Ct. 294, 95 L.Ed. 657, and Evans v.

Buchanan, 3 Cir., 1958, 256 F.2d 688,«

the District Court had issued mandatory

injunctions directing the admission of

Negro students. In Boson v. Rippy, 5

Cir., 1960, 275 F.2d 850, the appeal was

from a refusal to modify an injunction

so as to advance the dates of desegrega

tion, this falling within another provi

sion of § 1292(a) (1). The single case

that may support appealability here is

an unreported memorandum in Mapp v.

Board of Education of Chattanooga, in

which the Sixth Circuit denied a motion

to dismiss an appeal, without discussion

save for a reference to 28 U.S.C. § 1291

and § 1292(a) (1) and a “ cf.” to Boson

v. Rippy, supra. We doubt that appellees’

attempt to distinguish the Mapp case is

successful, but we do not find the memo

randum persuasive. Boson v. Rippy does

not support the decision, for the reason

indicated, as the manner of its citation

perhaps recognized; and we do not know

what it was that the judges found in the

statutes to support their conclusion of

appealability. Moreover, the subsequent

proceedings in the Mapp case, where the

District Court has already rejected the

plan directed to be filed and required the

submission of a new one, with a second

appeal taken from that order although

the first appeal has not yet been heard,

indicate to us the unwisdom of following

that decision even if we deemed ourselves

free to do so.

There is a natural reluctance to dis

miss an appeal in a case involving issues

so important and so evocative of emotion

as this, since such action is likely to be

regarded as technical or procrastinating.

Although we do not regard the policy

question as to the timing of appellate

review to be fairly open, we think more

informed consideration would show that

the balance of advantage lies in withhold

ing such review until the proceedings i

the District Court are completed. To

stay the hearing in regard to the remedy,

as appellants seek, would produce a delay

that would be unfortunate unless we

should find complete absence of basis for

any relief— the only issue that would

now be open to us no matter how many

others might be presented, since we do

not know what the District Judge will

order— and if we should so decide, that

would hardly be the end of the matter.

On the other hand, to permit a hearing

on relief to go forward in the District

Court at the very time we are entertain

ing an appeal, with the likelihood, if not

indeed the certainty, of a second appeal

when a final decree is entered by the Dis

trict Court, would not be conducive to

the informed appellate deliberation and

the conclusion of this controversy with

istent with order, which the

S rrp re fflrtS ^ ought

to be the objective of all concerned. In

contrast, prompt dismissal of the appeal

as premature should permit an early con

clusion of the proceedings in the District

Court and result in a decree from which

defendants have a clear right of appeal,

and as to which they may then seek a

stay pending appeal if so advised. We—

and the Supreme Court, if the case should

go there—can then consider the decision

of the District Court, not in pieces but

as a whole, not as an abstract declaration

inviting the contest of one theory against

another, but in the concrete. We state

all this, not primarily as the reason for

our decision not to hear an appeal at this

stage, but rather to demonstrate what

S.Ct. 1401, 3 L.Ed.2d 5 ; Aaron v. Coop

er, 8 Cir., 1958, 261 F.2d 97, concerned

attempts to frustrate or delay effectua

tion of the plan previously approved.

4- The Court of Appeals noted in the

Evans opinion, 256 F.2d at page 691,

that in one of the seven cases the D is

trict Court had earlier made an order

directing the submission of a plan from

■which “ an appeal * * * was taken to

this court hut was not prosecuted and ac

cordingly the record was returned to the

court below.” The later appeal. Evans v.

Ennis, 3 Cir., 1960, 281 F.2d 383, was

from a final order approving a plan which

plaintiffs deemed inadequate.

.. jga : . ' - V.. o- .. . ~ V. v "./ft-*: \ • . ( V .->■ O „o Mg £ VO" ' g' • O•- .. ■ - o' ' ■ , O. O' ' ' -- •-.* ';W O

{g p ^ f I

.̂; ,*/=̂?y> . C ; ' ̂-. f i-v;:.- - -i- i;̂ ■?:'---̂ > .-̂-; i.-̂-%' 0̂-f̂-ŝ.s.w i;-,

m *

»sU’;̂ C &£i£*? .

_ »■!.•-•- W .' ' -’ fyp*' -■ > ■^•--r- y •*■

.... ............ -a**— fe*f!3;'.;iX;: . ; -

':1Ww !

- # i

#8>m

■ a

- ■ a .

a

st

'•If

.'-31

, ' f

- 4

f

c f

%#

'■tf-

I

5*5 * - - • •

: ■ ■■ ;

‘ ‘f- §

■■

. ■#***&> :■ *

VV -VxSii'

: . ' ;:2 sSlfc ;

. ..

. . . . . . . . . . '

̂ "■ -

r- -sa ]

’iy .. i

%-■. -n

■■■ : a

* 1

& it !}-- -

608 288 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

we consider the wisdom embodied in the

statutes limiting- our jurisdiction, which

we would be bound to apply whether we

considered them wise or not^y

Accordingly, the appeal is dismissed

for want of appellate jurisdiction at this

time. Although it should not be neces

sary to do so, we add, from abundant

caution, that this dismissal involves no

intimation on our part with respect to

the propriety or impropriety of the de

termination of the District Court. If

defendants feel that the time that has

been required for the disposition of this

issue compels them to request a further

extension of the date for presenting a

plan, they should make their application

to the District Judge.

MOORE, Circuit Judge (dissenting).

This case comes before us on a motion

for a stay of that portion of a decree

wherein the Board of Education of New

Rochelle is “ ordered to present to this

Court [Irving R. Kaufman, D./J.], on or

before April 14, 1961, a plan for deseg

regation 1 in accordance with/ this [his]

Opinion * * * . ” An appeal “ from

the judgment entered in this action on

January 24, 1961” (the date judgment

was entered by the Clerk upon the trial

court’s opinion which was to constitute

the court’s findings of fact and conclu

sions of law) is now pending in this court

and representations have been made that

it can lie heard at a comparatively early

date. Upon oral argument of the motion,

the court on its own motion raised the

question of appealability; the parties

themselves initially did not present this

issue either by motion or on argument.

How the panel of this court which might

have heard the appeal would have ruled

on the question of appealability is aca

demic because by the decision of the ma

jority of this panel, they will not have

that opportunity. I would have deferred

to them and let them have the privilege

The schools of New Rochelle have never

been on a segregated basis in the sense

that :my Negro pupil has been denied ad

mission to any school by reason of being

a member of the Negro race and as the

of deciding whether they should hear and

decide on the merits. However, havinir

to face this question now, I am of the

opinion that an appeal may properly be

taken from the judgment as entered.

The complaint, charging maintenance

of “ a racially segregated public elementa

ry school,” “ ghettos,” “ minority racial

groups,” and denial of “ due process” and

“ equal protection,” seeks injunctive re

lief, both affirmative and negative,

against the Board:

A. Declaring illegal and unconstitu

tional the City’s “ neighborhood school”

policy (whereby children attend the

school in the area of their residence);

B. Enjoining attendance in a “ racial

ly segregated” school;

C. Requiring registration in a “ ra

cially integrated” school;

D. Enjoining the construction of a

public school approved for construction;

and

E. Enjoining prosecution of an action

commenced by the defendants.

The character of the action as an in

junction proceeding was clearly establish

ed by the allegations and the relief

sought. A trial was held and a judgment

was entered. The trial court throughout

its opinion referred to the injunctive re

lief sought, which was granted in both

mandatory and prohibitory form.

Section 1292(a) (1) gives this court

appellate jurisdiction over interlocutory

orders “ granting * * * injunctions.”

As the majority concedes, the term “ in

junction” embraces an order command-,

ing as well as prohibiting conduct. The

decree (entered as a judgment) in my

opinion definitely is within this category.

The words are “ the Board is hereby or

dered to present to this Court * * *

a plan for desegregation in accordance

with this Opinion.” The majority .-ay

that if the order in effect prohibited the

Board from reconstructing the Lincoln

term is used in Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. GSG, and re

lated cases. All the schools had Negro

pupils in their student bodies.

; ;V. i- . ' v , i ts.*- fJsjs„yi. f.fflf;;

;rnmm

,V -V '• >-v-v- ; v-. •- - . •' -4!

- - « ■ * . ,v„, . -- - - 1

w p ? • .

. ■ ■ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ■ - ... . . ■ f '

, "v v ̂ - < _ •• ■ - .

■' .; - : ;

e"!c

' - U • ■ :• - - - - - - ■■4 - ..... ■--

':A <

. ’ ’<& I

■ ■ ' • ; ■ ̂ i ' :" " - - •

§ - "•.4rSS$

i t*<.U*r-P .» ..?.?. ;•.—‘K" '•'• r, .»:;;• •i.'.'s<1.; .i*-.-.;V:i....'.X •?. ■- fews .'•■>; • * ..yj ,-* ŝ a- - - . - . ^ • * *s i& 6V

* * -

& ^aa&>: iiSiatai .sas^® w «

•<

,......,■ ., .,&*&•,=* -4f'■-*•̂ twS1' <,. D*£toŵsui-' ?«

TA1 .uCXl v. iiOxiiwD Ox

Cite as 288 F.2tl

School, the order would be “ clearly ap

pealable.” Yet in the “ Opinion” which is

to serve as a guide for a Plan, the trial

court has said, “ this [the rebuilding]

seems the one sure way to render certain

continued segregation at Lincoln.” How

can this statement, together with the

finding that “ it is most difficult to con

ceive of the rebuilding of the Lincoln

School as good-faith compliance with an

obligation to desegregate,” be reconciled

with the thought that no injunction is in

tended. Here is virtually a pre-hearing

judgment that any Plan which incorpo

rates a rebuilding of the school on its

present site will be inconsistent with the

court’s conception of desegregation. My

colleagues cannot seriously believe that

these words are not words of restraint

and should not be regarded as an injunc

tive deterrent from building a new

school. No Board would spend thousands

of dollars for a new school only to be

directed eventually to tear it down and

build it elsewhere.

The mandatory provisions of the judg

ment are both direct and implied. If

“ the presence of some 29 white children

certainly does not afford the 454 Negro

children in the school the education and

social contacts and interaction envisioned

by Brown,” how many additional white

children will be required to accomplish

this result ? 2 And where will they come

from? The trial court does not “con

ceive it to be the court’s function to in

terfere with the mechanics of the opera

tion of the New Rochelle school system,”

and “ did not strike down the neighbor

hood school policy,” but found it to be

“ valid only insofar as it is operated with

in the coniines established by the Con

stitution.” Yet the Board must submit

2. How can any court be sure that mere

numbers can effect these assumed ad

vantages?

3. Here the word is used to indicate a

predominant percentage of any race—

quite a different meaning from that in

tended in the true “ desegregation” cases.

EDUCATION, ETC. 607

(300 (1961)

an acceptable Plan in the light of the

Court’s Opinion to “ avoid that very even

tuality,” namely, “ the Court’s taking over

the running of the New Rochelle school

system.”

Reference to these situations is made

only because I believe that they relate to

the injunctive character of the judgment.

It is this character which determines ap

pealability— the only question now being

considered. The merits must be con

sidered later upon hearings in which it

would appear that the Lincoln School and

the Negro pupils will not be alone. Al

ready notice has been served that “ the

Ward School is predominently [sic]

Jewish and the Columbus School pre

dominently [sic] Italian in the composi

tion of the student bodies.” The parents

of the children “ desire that action be

brought to desegregate 3 both schools.”

Warning is given that “ if plans are made

to correct the situation existing in the

Lincoln School, brought about by the

neighborhood school concept, that such

plans also bear in mind the religious and

other inbalances [sic] also existing.”

When all the racial, religious and “ other

inbalances” have been thoroughly aired,

although, premature at this time, the

hope is expressed that somehow the

American philosophy that constitutional

rights are the vested heritage of all our

citizens and are not the exclusive prop

erty of any racial or religious group to be

used for their own particular interests

may find its way into the Plan— even if

only in a footnote.4

Because I believe that the statute per

mits an appeal from this injunctive judg

ment, I would grant the stay, and I dis

sent from the dismissal of the appeal.

4. Every assurance of this approach is giv

en in the two well-reasoned opinions be

low. My dissent is based solely upon the

belief that under the law the judgment

entered in this ease granting the relief

specified therein is appealable.

1

■

r r ■ rr - •r.wrgj

• ■: -ni

■ 1 - .*j

■ "4

, K i . . . . .