Letter from Lani Guinier to Solomon Seay re Bozeman

Correspondence

July 15, 1982

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Letter from Lani Guinier to Solomon Seay re Bozeman, 1982. 0a653fff-e392-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/89288066-7fce-4857-808b-588458ee2760/letter-from-lani-guinier-to-solomon-seay-re-bozeman. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

L*,EerenseH.

Solomon Seay, Esq.

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 3610/,

a .,. . .-.>.iiL:L ,

NAACP LEGAL OEFENSE ANO EDUCATIONAL FUNO, INC.

10 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019. (212) 586-8397

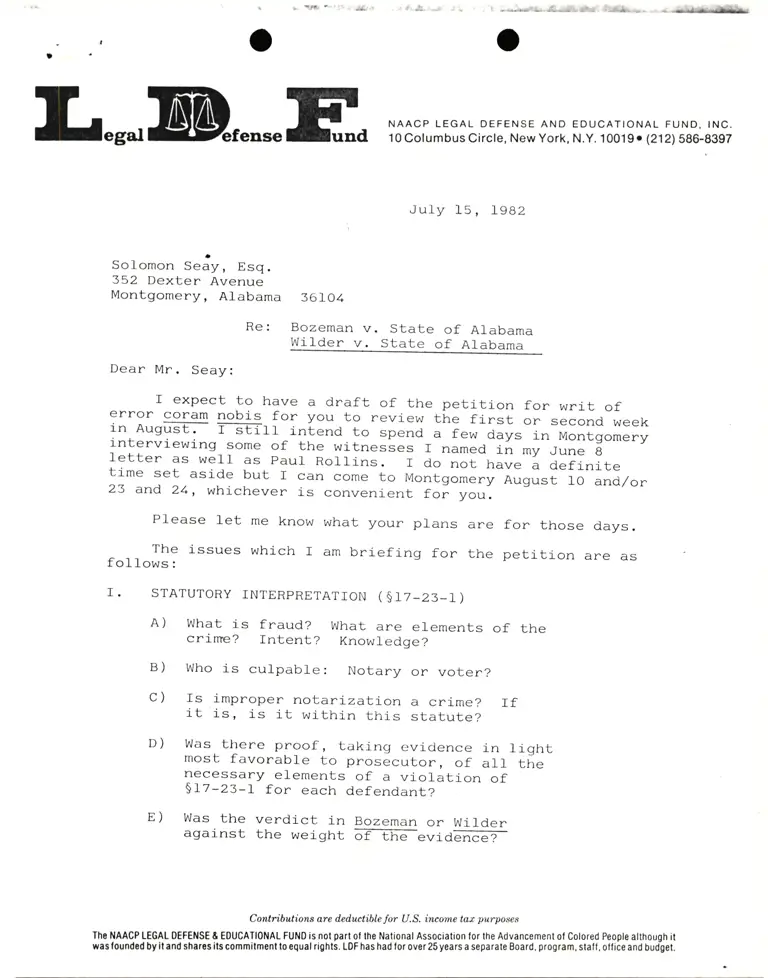

July 15, 1982

Re: Bozeman v. State of

Wilder v. State of

Al-abama

Al-abama

Dear Mr. Seay:

r expect to have a draft of the peti-tion for writ oferror coram ,-,obl?_ for you to review the f irst or second weekin euguEE.-- T-GETrr intend to spend a few days in Montgomeryinterviewing some of the witne=ses r named in my June Bl-etter as wefr as paur Rorrlns. r do not have a defini_tetime set aside but r can come to Montgomery August 10 and/or23 and 24, whichever is convenient for you.

Please Iet me know what your plans are for those days.

The i-ssues which r am briefing for the petition are asfoI lows :

I. STATUTORY INTERPRETATTON ( $17-23-I )

A) What is fraud? What are elements of thecrinre? Intent? Knowledge?

B) Who is culpable: Notary or voter?

C) Is improper notarization a crime? Ifit is, is it within this statute?

D) Was there proof, taking evidence in lightmost favorable to prosecutor, of all thenecessary elements of a violation of

S17-23-1 for each defendant?

E) Was the verdict in Bozeman or Wi1deragainst the weight oFtEe eviderrcET-

Contributions are d.eductible tor U.S. income tar purposes

Tho NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND is not parl ol the National Association ,or lhe Advancement ol Colored People although it

was lounded by it and shares its commilmenl to equal rights. LDF has had lor over 25 years a separate Board, pro0ram, slal,, olfice and budget.

Solomon Seay, Esg.

JuIy 15, L9B2

Page 2

II. DID THE COURT ERR TN TTS INSTRUCTIONS TO THE JURY?

A) Did court instructions exceed charges in

J-). Perjury with regard to Wilder

2) Conspi.racy with regard to Bozeman.

B) Where no exception taken by counsel. (Fed.

RuIe 51, CRIM RuIe 52(b) ).

C) Was failure to provide Iimiting instructions

' regarding use of depositions plain error, in

Iight of age and vul-nerability of the witnesses?

III. WAS STATUTE CHARGED IN IND]CTMENT UNCONSTITUTIONAL

AS APPLIED IN LIGHT OF THREE QUESTIONS?

A) Chilling effect on the exercise of the right to

vote.

B) Does the change of Alabama law with respect to

absentee ballots make the convi-ctions no

Ionger valid?

(See Abatement Cases and analysis re:

application to pending cases BelI, Griffin,

Hamm) .

C) Is there a constitutional right to a secret

baI Iot?

IV. PROSECUTIONIS USE OF DEPOS]TION TESTIMONY

A) Defense counsel not present.

B) Depositions used as impeachment evidence with-

out Iimiting i-nstructions, and over objections

by defense counsel.

C ) Was there a sufficient basis for declaning

witnesses hostile?

I ) What are the rules governing impeach-

ment of own witnesses.

2) What about rules for inconsistent testi-

mony in this regard.

SoLomon Seay, Esq.

July 15, LgB2

Page 3

D) Must the prosecution turn over aII exculpa-

tory evj-dence? See Brady v. Maryland.

E) Was the jury decision affected by the use

of the deposition testimony?

a

1 ) In the Bozeman trial, there was no

evidencS-to convict except if deposi-

tions used as substantive evidence.

2) Since the evidence was so confusing,

bhe jury had no way to distinguish

between credibility and substantive

evidence.

3) The prosecutor relied on the deposition

testj-mony to prove his case in chief .

F.) Even in the absence of a request from defense

counsel for a limiti_ng instpuction, it was plain

error for the court to allow the use of deposi-

tion testimony for impeachment purposes without

advising the jury of the limited use of such

testimony. I

In addition, we are researching two other issues: (I)

were the sentences excessive with respect to the crime charged?

and (2) what are the standards for relief in a petition for

Writ of Error?

Pl-ease call- me to let me know whether you see additional

issues that we have missed. Al-so l-et me know your August

schedule.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

Lani Guinier

18 53

18 54

18 55