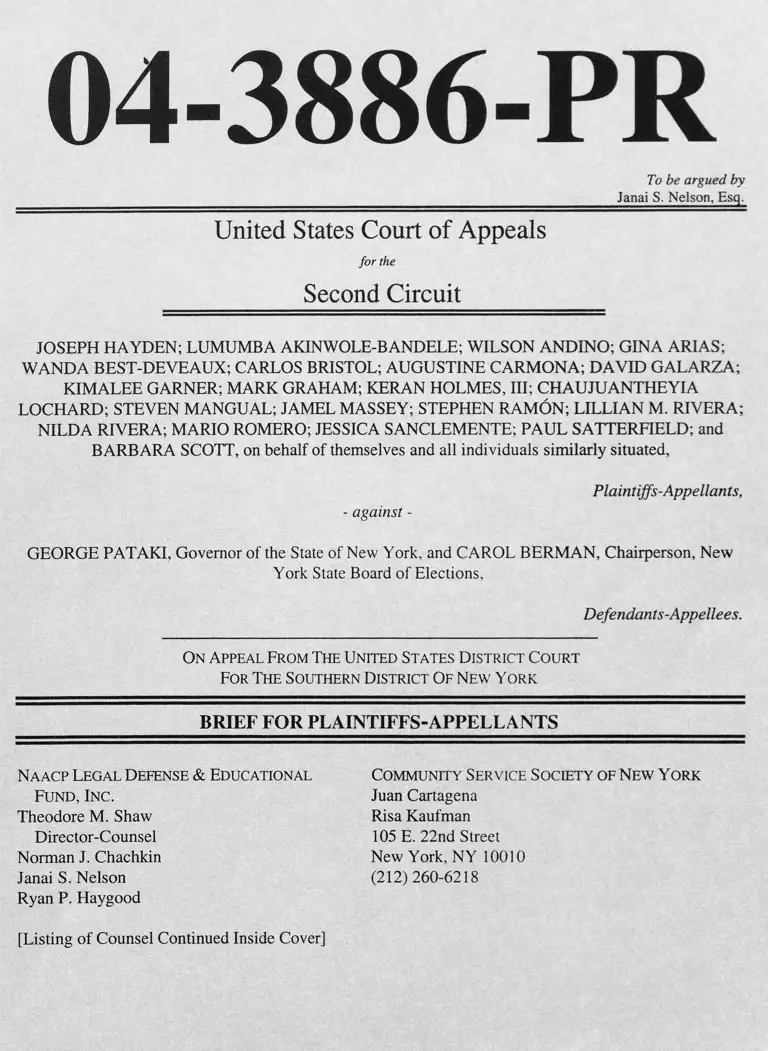

Hayden v. Pataki Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

September 27, 2004

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hayden v. Pataki Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 2004. 700608d5-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8949fb0b-d2d9-4d15-bb1d-6396ecd9c62f/hayden-v-pataki-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

04-3886-PR

To be argued by

__________ ____________________________________________________________________ Janai S. Nelson, Esq.

United States Court of Appeals

for the

Second Circuit

JOSEPH HAYDEN; LUMUMBA AKINWOLE-BANDELE; WILSON ANDINO; GINA ARIAS;

WANDA BEST-DEVEAUX; CARLOS BRISTOL; AUGUSTINE CARMONA; DAVID GALARZA;

KIMALEE GARNER; MARK GRAHAM; RERAN HOLMES, III; CHAUJUANTHEYIA

LOCHARD; STEVEN MANGUAL; JAMEL MASSEY; STEPHEN RAMON; LILLIAN M. RIVERA;

NILDA RIVERA; MARIO ROMERO; JESSICA SANCLEMENTE; PAUL SATTERFIELD; and

BARBARA SCOTT, on behalf of themselves and all individuals similarly situated,

- against -

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

GEORGE PATAKI, Governor of the State of New York, and CAROL BERMAN, Chairperson, New

York State Board of Elections,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of New York

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Naacp Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc .

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Janai S. Nelson

Ryan P. Haygood

Community Service Society of New York

Juan Cartagena

Risa Kaufman

105 E. 22nd Street

New York, NY 10010

(212) 260-6218

[Listing of Counsel Continued Inside Cover]

Naacp Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc. (cont’d)

Debo P. Adegbile

Alaina C. Beverly

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Center for Law and Social Justice

at Medgar Evers College

Joan P. Gibbs

Esmeralda Simmons

1150 Carroll Street

Brooklyn, NY 11225

(718) 270-6296

Attorneys fo r Appellants

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society of

New York, and the Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College, by

and through the undersigned counsel, make the following disclosures:

Counsel for plaintiffs-appellants, all not-for-profit corporations of the State

of New York, are neither subsidiaries nor affiliates of a publicly owned

corporation.

Janai S. Nelson, Esq.

Director of Political Participation

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

inelson@naacpldf.org

i

mailto:inelson@naacpldf.org

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT........................................................... i

TABLE OF CONTENTS............................................................................................... ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES......... ............................. iv

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT.............................................................. 1

STATEMENT OF SUBJECT MATTER AND JURISDICTION ............................2

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW....................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE......................................................................................3

STATEMENT OF FACTS................................................................................. 5

A. New York’s Felon Disfranchisement Laws.............................. 5

B. The Amended Complaint....................................................... 6

C. The Public Record......................................................................................... 10

D. The District Court’s Opinion Regarding the Claims on Appeal..............14

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT..........................................................................16

STANDARD OF REVIEW............... 16

ARGUMENT......................................................................................................... 17

I. The District Court Substantially Misapplied the Standard for

Dismissal Under Rule 12(c)............. 17

A. The District Court’s Premature Dismissal of Plaintiffs’

Amended Complaint is Contrary to the Law of this Circuit

and Supreme Court Precedent...........................................................19

ii

II. Plaintiffs Met the Pleading Requirements of Rule 8(a) by Alleging

Facts that Put Defendants on Notice of Their Claims, and of

Rule 12(c) by Setting Forth Sufficient Facts to State Legally

Cognizable Causes of Action................................................................ 23

A. Intentional Discrimination Claim................................ 26

1. Elements of an Intentional Discrimination Claim............. 26

2. The District Court Incorrectly Applied the Pleading

Standard and Mischaracterized the Allegations in the

Amended Complaint............................. 28

B. Applying Rational Basis Review in a Wholly Deferential

Manner, the District Court Dismissed Plaintiffs’ Claim that New

York State’s Non-uniform Felon Disfranchisement Scheme

Violates Equal Protection Guarantees prior to Affording Plaintiffs

the Opportunity to Develop and Present Evidence Regarding

Defendants’ Justifications for the L aw ...........................................35

1. The district court erred in dismissing Plaintiffs’

equal protection claims without subjecting §5-106

to strict scrutiny......................................................................37

2. Even if rational basis is the appropriate level of review

for Plaintiffs’ equal protection claims, the district court erred

in applying the standard in a wholly deferential manner

and finding a rational basis for New York’s felon

disfranchisement regime.......................................................40

C. Voting Rights Acts Claims...................................... 42

CONCLUSION 43

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Pages

Beniamin v. Jacobson,

124 F.3d 162 (2d Cir. 1997), vacated on other grounds,

172 F.3d 144 (2d Cir. 1999)........................................................................37

Burdick v. Takushi,

504U.S.428 (1992)...................................................................... .......38, 39

City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc.,

473 U.S. 432 (1985).....................................................................................37

Conley v. Gibson,

355 U.S. 41, 47 (1957)...........................................................................21,22

Davis v. Beason,

133 U.S. 333 (1890).............................................................................. 42n.9

De Jesus v. Sears, Roebuck & Co.,

87 F.3d 65 (2d Cir. 1995)......................................................................17n.5

DeMuria v. Hawkes,

328 F.3d 704 (2d Cir. 2003).....................................................19, 20, 24, 36

Dioguardi v. Duming,

139 F.2d 774 (2d Cir. 1944)........................................................................20

Dunn v. Blumstein,

405 U.S. 330 (1972)..................................................................... 38,41 n.10

Dwyer v. Regan,

777 F.2d 825 (2d Cir. 1985), modified on other grounds,

793 F.2d 457 (2d Cir. 1986)....................................................................... 20

Farrakhan v. Washington,

359 F.3d 1116 (9th Cir. 2004), petition for cert, filed,

72 U.S.L.W. 3741 (U.S. May 24, 2004)................................... ............... .42

Friedlander v. Cimino,

520 F.2d 318 (2d Cir. 1975)....................................................................... 22

IV

Cases (cont’d) Pages

Geisler v. Petrocelli,

616 F.2d 636 (2d Cir. 1980)....................... ......................................... 20, 24

Hayden v. Pataki,

No. 00 Civ. 8586, 2004 WL. 1335921 (S.D.N.Y. June 14, 2004).... 17, 39

Heller v. Doe, ex rel. Doe,

509 U.S. 312 (1993)............................. ............... ............ .......................... 42

Hunter v. Underwood,

471 U.S. 222 (1985)................ ................................................ 27, 32, 33, 34

Irish Lesbian & Gay Organization v. Giuliani,

143 F.3d 638 (2d Cir. 1998)................................................................. 18, 20

Kramer v. Union Free School District No. 15,

395 U.S. 621 (1969)..................................... ........... ...................................37

McDonnell Douglas Com, v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973).............. ......................................................... 21, 21 n.6

Muntaqim v. Coombe,

366 F.3d 102 (2d Cir. 2004), petition for cert, filed,

73 U.S.L.W. 3113 (U.S. July 21, 2004)............................... 4, 5, 16, 42, 43

Nagler v. Admiral Corp.,

248 F.2d 319 (2d Cir. 1957)....................................... ............................... 21

Norman v. Reed,

502 U.S. 279 (1992)..................................................................... ..............38

Patel v. Contemporary Classics of Beverly Hills,

259 F.3d 123 (2d Cir. 2001)................................................. ...............18, 19

Phillip v. University of Rochester,

316 F.3d 291 (2d Cir. 2003)..... 22

Cases (cont’d) Pages

Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533 (1964)................................................................................... 38

Romer v. Evans,

517 U.S. 620(1996)............ ........................ ................................... ....40,41

Ryder Energy Distributing Corn, v. Merrill Lynch Commodities, Inc.,

748 F.2d 774 (2d Cir. 1984).......................................................................20

Salahuddin v. Cuomo,

861 F.2d 40 (2d Cir. 1988).................................................................. 22, 23

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974),

overruled on other grounds. Davis v. Scherer,

468 U.S. 183 (1984).............. ....................................................................29

Scutti Enterprises. LLC v. Park Place Entertainment Com.,

322 F.3d 211 (2d Cir. 2003).......................................................................19

Shechter v. Comptroller of the City of New York,

79 F.3d 265 (2d Cir. 1996).........................................................................20

Swierkiewicz v. Sorema, N.A.,

534 U.S. 506 (2002)..................................................................... 21, 22, 29, 34

Underwood v. Hunter,

730 F.2d 614 (11th Cir. 1984), aff, 471 U.S. 222 (1985)....................... 33

Vargas v. City of New York,

377 F.3d 200 (2d Cir. 2004).......................................................................16

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development

Com., 429 U.S. 252 (1977).............................................. 24, 27, 28, 30, 31

Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229(1976)................................................................................... 28

vi

Cases (cont’d) Pages

Williams v. Apfel,

204 F.3d 48 (2dCir. 1999).......................................................................... 19

Williams v. Taylor,

677 F.2d 510 (5th Cir. 1982)............... ....................................................... 39

Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 356 (1886)....... .............................................................................38

Ziemba v. Wezner,

336 F.3d 161 (2d Cir. 2004))].....................................................................17

Constitutions, Statutes & Rules

U.S. Const, amend. XIV, § 1.......... ......... .................................. .................. 27

N.Y. Const. (1821), art. II, § 1 (repealed 1870)........................... 12

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 ........................................................................................ 9

N.Y. Const. (1821), art. II, § 2 ...........................................................................7

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 (amended 1894).......................................................... 8,9

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 3 ....................................................................... 5

28 U.S.C. §§ 1331............................................................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §§ 1343...................................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. §§ 1973........................................................................ 1,2

42 U.S.C. §§ 1983....................................................................... 2

Fed.R.Civ.P. 8 ............................................................................................passim

Fed.R.Civ.P. 12..........................................................................................passim

N.Y.Elec. Law § 5-106.........................................................................3, 5, 9, 16

vii

Miscellaneous

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess...................................................................14

Constitutional Convention of 1846, Debates of 1846............. ..................... 12

Documents of the Convention of the State of New York,1867-1868,

No. 16, 3, Vol. One (Albany: Weed, Pearsons & Co. 1868 ) ............13, 14

Nathaniel Carter, William Stone, & Marcus Gould,

Reports of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1821,

(Albany: E. & E. Hosford, 1821)......... .............................................10, 11

New York State Constitutional Convention Committee,

Problems Relating to Home Rule and Local Government,

(Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Co., 1938)..........................................................12

viii

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

Plaintiffs-Appellants (hereinafter, “Plaintiffs”) seek to challenge the New

York State laws that deny the franchise to voting-age citizens incarcerated or on

parole for a felony conviction on the grounds that such laws (1) were enacted with

the intent to discriminate against African Americans, (2) have the present-day

effect of disfranchising African Americans and Latinos on account of race at a rate

vastly disproportionate to Whites, and (3) are applied unequally among persons

convicted of a felony in New York State. Plaintiffs appeal from those portions of

the final judgment and order of the United States District Court for the Southern

District of New York (Hon. Lawrence M. McKenna, J.) dated and entered on June

14, 2004, dismissing Plaintiffs’ claims for relief under the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution, the Fifteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution, and Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1973, et seq, (“Voting Rights Act” or

“VRA”). The premature dismissal of Plaintiffs’ claims is directly contrary to

controlling precedent of the Supreme Court and this Court concerning pleading

requirements generally and the elements of equal protection claims in particular

and, therefore, should be reversed.

1

STATEMENT OF SUBJECT MATTER

AND APPELLATE JURISDICTION

Plaintiffs’ claims for declaratory and injunctive relief arise under the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution and under

§ 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Thus, the district court had subject matter

jurisdiction over Plaintiffs’ claims pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343, and 42

U.S.C. §§ 1973(f) and §1983. The final judgment and order dismissing Plaintiffs’

claims was entered on June 14, 2004. On July 13, 2004, Plaintiffs filed their notice

of appeal in the district court.

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

I. Whether the district court improperly and against the weight of relevant case law

heightened the pleading requirements for Plaintiffs’ amended complaint in

dismissing their claims under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(c).

II. Whether Plaintiffs’ amended complaint, which alleges that New York’s felon

disfranchisement laws were originally enacted with the intent to exclude Blacks

from the franchise, states a claim under the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment and under the Fifteenth Amendment.

III. Whether Plaintiffs’ amended complaint, which alleges that, without adequate

justification, New York law disfranchises only those persons with felony

convictions who are incarcerated or on parole, but not persons receiving other

2

sentences for felony convictions, states a claim under the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

IY.Whether the district court erred in applying a wholly deferential standard of

rational basis review to Plaintiffs’ equal protection claim against New York’s non-

uniform practices of disfranchising only those persons with felony convictions who

are incarcerated or on parole and in finding a rational basis for such practices.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case was originally filed pro se by plaintiff Joseph Hayden on

November 9, 2000, in the Southern District of New York, alleging that New York

Election Law § 5-106, which prohibited him from voting in New York solely

because of his felony conviction and incarceration, violated his rights under the

Voting Rights Act and under the U.S. Constitution. Defendant Carol Berman,

Chairperson of the New York State Board of Elections (“Berman”), and

Defendants George Pataki (“Pataki”), Governor of the State of New York, and

Glenn Goord, Commissioner of New York State Department of Correctional

Services (“Goord”), filed answers on January 5, 2001 and on February 28, 2001,

respectively.

On January 15, 2003, Hayden, on parole, but, nonetheless disfranchised by

operation of New York’s felon disfranchisement laws, moved (by and through the

undersigned attorneys) for leave to file an amended complaint for declaratory and

3

injunctive relief. Judge McKenna granted this motion on February 21, 2003. The

amended complaint added new plaintiffs1 2 and expanded the claims in this action

against defendants Pataki and Berman in their official capacities. The Amended

Complaint includes detailed allegations in support of the Constitutional and Voting

Rights Act claim of intentional discrimination in the original enactment of New

York’s felon disfranchisement laws, as well as claims under the First Amendment,

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Civil Rights Acts of

1957 and 1960, and customary international law. Defendants Berman and Pataki

answered this amended pleading on April 8, 2003, and April 14, 2003,

respectively.

On April 10, 2003, Judge McKenna denied Defendants’ motion to stay

discovery until this Court adjudicated Muntaaim v. Coombe, 366 F.3d 102 (2d Cir.

2004), pet, for cert, filed, 73 U.S.L.W. 3113 (U.S. July 21, 2004) (No. 04-175), a

pro se case challenging New York’s felon disfranchisement laws under the Voting

1 The additional Plaintiffs may be grouped within three separate subclasses: a)

Blacks and Latinos eligible to vote but for their incarceration for a felony

conviction; b) Blacks and Latinos eligible to vote but for their parole for a felony

conviction; c) Black and Latino voters who reside in specific communities in New

York City and whose collective voting strength is unlawfully diluted because of

New York’s disfranchisement laws. Plaintiffs filed a motion to certify these

subclasses on November 3, 2004, which the district court denied as moot in its

June 14, 2004 judgment and order granting Defendants’ Motion for Judgment on

the Pleadings.

2 Goord was not named as a defendant in the amended complaint and is no longer a

party to this action.

4

Rights Act. Discovery by all parties commenced pursuant to a scheduling order

issued by Magistrate Judge Henry Pitman on May 19, 2003. Defendants filed a

motion for judgment on the pleadings in July 10, 2003 and Plaintiffs filed a brief in

opposition in September 9, 2003.

All parties actively engaged in discovery through June 14, 2004, at which

time Judge McKenna issued a final Memorandum and Order granting Defendants’

Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings in its entirety. The district court held that

Plaintiffs’ Voting Rights Act claims must be dismissed in light of the ruling by a

panel of this Court earlier this year in Muntaqim v. Coombe, which held that the

VRA does not apply to felon disfranchisement laws. The court below further held

as a matter of law that Plaintiffs had not alleged facts sufficient to state claims

against Defendants under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. This appeal

followed.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. New York’s Felon Disfranchisement Laws

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 3 provides that “[t]he Legislature shall enact laws

excluding from the right of suffrage all persons convicted of bribery or any

infamous crime.”3 Id. New York Election Law § 5-106(2) provides:

3 The term “infamous crime” has come to mean felony under New York State

law. (JA 00107 [FAC 149]).

5

No person who has been convicted of a felony pursuant to the laws of the

state, shall have the right to register for or vote at any election unless he shall have

been pardoned or restored to the rights of citizenship by the governor, or his

maximum sentence of imprisonment has expired, or he has been discharged from

parole. The governor, however, may attach as a condition to any such pardon a

provision that any such person shall not have the right of suffrage until it shall have

been separately restored to him.

B. The Amended Complaint

In eighteen separate allegations in their amended complaint (Joint Appendix

(“JA”) 00105-109 [First Amended Complaint (“FAC”) f l 39 - 57]), Plaintiffs

outline over one-hundred years of constitutional history in New York and made

allegations of specific acts of intentional discrimination to deny the franchise to

Blacks.

The allegations of the amended complaint detail how the framers of the New

York State Constitution in 1777 intentionally excluded Blacks from the polls by

limiting suffrage to property holders and free men (JA 00106 [FAC 1 43]),

requirements that disproportionately disfranchised Blacks. Id. Further, when in

1801 the legislature removed all property restrictions from the suffrage

requirements for the election of delegates to New York’s first Constitutional

6

Convention, at the same time it expressly excluded Blacks from participating in

this election. (JA 00106 [FAC f 45]).

New York’s felon disfranchisement provisions originated in this historical

period, specifically at the Constitutional Convention of 1821 - a convention

dominated by an express, racist purpose to deprive the vote from “men of color.”

(JA 00107 [FAC 148]). Delegates clearly expressed their conviction that Black

New Yorkers were unequipped and unfit to be part of the democratic process (JA

00106-107 [FAC H 46-47]) and crafted new voting requirements that were aimed

at stripping Blacks of their previously held, albeit severely restricted, right to vote.

Id. Race-based suffrage requirements, such as heightened property requirements

applicable only to Blacks, were written into Article II of the New York State

Constitution. (JA 00107 [FAC 148]). The discriminatory effect of these measures

was evident; only 298 out of 29,701 Blacks, or less than 1% of the Black

population of the State, met these new requirements. Id. New citizenship

requirements were also devised and applied in a racially discriminatory manner.

Id.

The delegates to the 1821 Constitutional Convention also adopted a

provision that permitted the legislature to exclude from the franchise those “who

have been, or may be, convicted of infamous crimes.” (JA 00107 [FAC 1 49,

quoting N.Y. Const. (1821), art. II, § 2]). In 1826, the State Constitution was

7

amended to expand White male suffrage without any alteration of either the

onerous property requirements for Black males, or the felon disfranchisement

provision. (JA 00107 [FAC f 50]).

Delegates to New York’s 1846 Constitutional Convention made explicit

references to their belief that Blacks were unfit to vote. (JA 00107 [FAC J[ 51]).

They adopted a new Constitutional provision expanding the Legislature’s

authorization to deny the franchise to “all persons who have been or may be

convicted of bribery, of larceny, or of any infamous crime.” (JA 00107-108 [FAC

<f 52, quoting N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 (amended 1894)]). As in 1821, the delegates

to the 1846 Constitutional Convention acted with knowledge that felon

disfranchisement would disproportionately reduce the numbers of Black voters (JA

00108 [FAC f 53); one speaker, for example, noted that “the proportion of

‘infamous crime’ in the minority population was more than thirteen times that in

the white population.” (JA 00107 [FAC f 51]). The delegates were, therefore,

aware of the racially discriminatory impact of the felon disfranchisement law. (JA

00108 [FAC f 53]).

In the aftermath of the Civil War and the advent of Reconstruction, another

Constitutional Convention was convened in New York from 1866-67. At this

Convention, again the issue of equal manhood suffrage for Blacks was considered

8

but rejected. (JA 00108 [FAC f 54]). And the felon disfranchisement provision

was not removed or altered. Id.

It took the power of the federal government finally to bring equal manhood

suffrage to New York with the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870.

(JA 00108 [FAC f 55]). But two years after the passage of the Fifteenth

Amendment, an unprecedented committee convened to amend the New York State

Constitution’s disfranchisement provision to require the State Legislature, at its

following session, to enact laws excluding persons convicted of infamous crimes

from the franchise. (JA 00108 [FAC f 56], see, N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 (amended

1894)). Until that point, enactment of such laws had been permissive. (JA 00108

[FAC '[[ 56]). This new mandate for felon disfranchisement was reaffirmed at a

Constitutional Convention in 1894. (JA 00108-109 [FAC ][ 57]).

Plaintiffs’ allegations in their amended complaint thus describe the genesis

of present Article II, § 3 of the New York Constitution in the 1821 and 1846

Constitutional Conventions, reaffirmed and extended in 1872 and 1894, and which

resulted in New York Election Law § 5-106 under which Blacks and Latinos

incarcerated and on parole for felony convictions are presently disfranchised in

New York State.

9

C. The Public Record

In addition to the allegations in the amended complaint, which by

themselves suffice to state cognizable claims against defendants, the district court

below had before it numerous references from the public record, the laws of New

York, and historical scholarship that supported and elaborated upon the detailed

allegations in the amended complaint that race, indeed, played a significant role in

the adoption of New York’s felon disfranchisement laws.4 These references

included the following:

1) At the New York Constitutional Convention of 1821 the question

of Black suffrage sparked heated debates during which delegates

expressed their views that Blacks, as a “degraded” people, and by

virtue of their natural inferiority, were unfit to participate in civil

society. Nathaniel Carter, William Stone, & Marcus Gould,

Reports of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1821,

4 Plaintiffs introduced these facts in opposition to Defendants' Motion for

Judgment on the Pleadings in order to provide additional context for their legally

sufficient allegations of intentional discrimination and to offer a sample of the

evidence that exists to support such claims. Plaintiffs provided these references

without the benefit of the full expert reports by the historians they retained, since,

as noted above, Judge McKenna’s decision was issued while the parties were in the

throes of discovery. Moreover, while this showing is not necessary to withstand a

motion for judgment on the pleadings, it provided the district court with ample

information with which to measure the strength of plaintiffs’ allegations.

10

at 198 (Albany: E. & E. Hosford, 1821) (hereafter “Debates of

1821”).

2) One delegate to the 1821 convention instructed his colleagues to

“[l]ook to your jails and penitentiaries. By whom are they filled?

By the very race, whom it is now proposed to cloth with power of

deciding upon your political rights.” Id at 191.

3) Another delegate to the 1821 convention urged the other delegates

to “[sjurvey your prisons - your alms houses - your bridewells and

your penitentiaries and what a darkening host meets your eye!

More than one-third of the convicts and felons which those walls

enclose, are of your sable population.” Id at 199.

4) As is made manifest by their own language, the delegates not only

understood that enacting the felon disfranchisement provision

would result in the disproportionate disfranchisement of Blacks, but

actively sought to preserve the franchise for Whites only: “[A]ll

who are not white ought to be excluded from political rights.” Id.

at 183.

5) As articulated by one delegate to the 1821 Constitutional

Convention, the new property qualification “was an attempt to do a

thing indirectly which we appeared to either be ashamed of doing,

11

or for some reason chose not to do directly . . . . This freehold

qualification is [for Blacks] a practical exclusion [from the

franchise].” New York State Constitutional Convention

Committee, Problems Relating to Home Rule and Local

Government, at 143 n.13 (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Co., 1938).

6) Heightening the requirements for Black voters previously outlined

in the New York State Constitution of 1777, delegates to the New

York Constitutional Convention of 1821 required that Black males

be citizens of New York for three years while Whites were only

required to be “inhabitants” for one year. N.Y. Const. (1821), art.

II, § 1 (repealed 1870).

7) Moreover, as an additional barrier to voting, in 1821 it was decided

that Blacks were required to possess a freehold estate worth $250

for the year preceding any election. Id

8) In the 1846 Constitutional Convention, the delegates continued to

advocate for the denial of equal suffrage to Blacks including one

delegate’s assertion that: “[Blacks] were an inferior race to whites,

and would always remain so.” Constitutional Convention of 1846,

Debates of 1846, at 1033 (hereafter “Debates of 1846”).

12

9) The understanding by the delegates that Blacks were thirteen times

more likely to commit “infamous crimes” than Whites, set out in

151 (JA 00107) of the amended complaint, was substantiated by a

citation to the record of those debates, Debates of 1846, at 1033.

10) Moreover, the delegates were well aware of and sought the same

the success of other slaveholding states in excluding Blacks from

the ballot. As one delegate suggested to the convention, “in nearly

all the western and southern states . . . the [Bjlacks are excluded . ..

would it not be well to listen to the decisive weight of precedents

furnished in this case also?” Id at 181.

11) In the 1866-67 Constitutional Convention, instead of abolishing the

suffrage distinction for Blacks, the delegates favored a separate

submission to the voters on the issue of equal Black suffrage. “[I]t

must be done by the direct and explicit vote of the electors. We are

foreclosed from any other course by the repeated action of the

State.” Documents of the Convention of the State of New York,

1867-68, No. 16, 3, Vol. One (Albany: Weed, Pearsons & Co.

1868) (hereafter “1867-68 Documents”).

12) Previous separate submissions to the voters on equal Black suffrage

had proven that it was an unsuccessful way to abolish the legacy of

13

the 1821 Convention. For instance, an 1846 referendum to extend

the franchise to Blacks failed by a vote of 85,306 to 223,884. In

1850, the reintroduced referendum failed by a vote of 197,503 to

337,984. Documents, No. 16, 3, Vol. One.

13) During Reconstruction, additional measures were taken that would

reveal the racial motivation of the state actors with regard to voting;

for example, after initially ratifying the Fifteenth Amendment, New

York withdrew its ratification. Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess.,

at 1447-81.

In short, the sampling of historical references that Plaintiffs highlighted to

the district court, even in the absence of full expert discovery, demonstrated to the

court that Plaintiffs could proffer evidence to bolster the specific allegations in

their amended complaint. The district court’s premature dismissal of Plaintiffs’

claims, however, foreclosed further development of the case.

D. The District Court’s Opinion Regarding the Claims on Appeal

In evaluating Plaintiffs’ claims for intentional discrimination, the district

court stated that Plaintiffs could withstand judgment on the pleadings “only if

[they] sufficiently allege[d] that New York’s decision to disenfranchise

incarcerated and paroled felons was motivated by discriminatory intent. (JA

14

00018 [00 Civ. 8586 Mem. & Order, at 7]). The court then referred to plaintiffs’

allegations in support of this claim and held that they do not “necessarily mean

New York Constitution Article II, § 3 and § 5-106(2) or their predecessors were

. . . enacted with [discriminatory] intent.” (JA 00019 [00 Civ. 8586 Mem. &Order,

at 8]). The court further held that “[t]he majority of allegations” in support of the

intentional discrimination claim are “entirely conclusory in nature,” stating that

only one of plaintiffs’ factual allegations “could possibly support a finding of

discriminatory intent.” (JA 00019 [00 Civ. 8586 Mem. & Order, at 8]). The

district court then determined that “this one allegation is simply an insufficient

basis, even under the liberal standards of a 12(c) motion, from which to draw the

inference that these provisions or their predecessor were enacted with

discriminatory intent.” (JA 00020 [00 Civ. 8586 Mem & Order, at 9]).

With respect to plaintiffs’ claim that New York’s non-uniform practices

violate equal protection guarantees, the district court did not explicitly challenge

the sufficiency of plaintiffs’ pleadings concerning this claim. Rather, the district

court applied a wholly deferential standard of rational basis review and asserted,

sua sponte, a justification for New York’s non-uniform felon disfranchisement

laws. (JA 00020-23 [00 Civ. 8586 Mem. & Order, at 9-12]). For these reasons,

the district court dismissed Plaintiffs’ well-pleaded claims for intentional

15

discrimination and non-uniform application of New York’s felon disfranchisement

laws,

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs alleged specific facts regarding the history of official

discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities in New York State, including

facts from which to infer intentional discrimination in the enactment of New

York’s felon disfranchisement provisions. Moreover, Plaintiffs specifically

alleged facts concerning the unequal application of New York Election Law § 5-

106(2) that set forth a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment because, Plaintiffs alleged, there is neither a compelling state interest

nor a rational basis for the distinction in the law or the resulting disparity. Because

these allegations easily satisfy the liberal pleading requirements under Rules 12(c)

and 8(a), the district court’s dismissal of Plaintiffs’ Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendment claims should be reversed. Moreover, the district court’s dismissal of

Plaintiffs’ VRA claims should be vacated pending disposition of the Petition for

Certiorari filed seeking review of this Court’s ruling in Muntaqim v. Coombe.

STANDARD OF REVIEW

An appellate court reviews the district court’s ruling on a Rule 12(c) motion

for judgment on the pleadings de novo. Vargas v. City of New York, 377 F.3d

200, 205 (2d Cir. 2004).

16

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Substantially Misapplied the Standard for

Dismissal Under Rule 12(c)

The district court substantially misapplied — and indeed heightened — the

pleading requirements under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(c) in deciding the

Defendants’ motion for judgment on the pleadings. Despite recognizing that Rule

12(c) requires it to “accept[] the allegations contained in the complaint as true and

draw[] all reasonable inferences in favor of the [Plaintiffs],” (JA 00015-00016

[Hayden v. Pataki, No. 00 Civ. 8586, 2004 WL 1335921, at *4-5 (S.D.N.Y. June

14, 2004), (quoting Ziemba v. Wezner, 366 F.3d 161, 163 (2d Cir. 2004))]), the

district court conducted a cursory analysis of Plaintiffs’ legally cognizable claims

and, without regard to relevant and controlling case law, granted Defendants’

motion. Moreover, the district court incorrectly held that plaintiffs’ amply-

pleaded complaint stated mere legal conclusions and did not set forth sufficient

factual allegations. Id.5

5 The district court incorrectly relied on the inapposite case of De Jesus v. Sears,

Roebuck & Co., 87 F.3d 65 (2d Cir. 1995), which held that conclusory allegations

unsupported by factual assertions are insufficient to satisfy 12(b)(6), to support its

improper dismissal of the plaintiffs’ complaint. In that case, however, this Court

upheld the dismissal of the plaintiffs’ complaint against a parent company for the

alleged fraudulent activity of its subsidiary because plaintiffs’ pleadings did not

allege “any specific facts or circumstances . . . from which it may be inferred” that

the parent company or its employees exercised actual domination over the

subsidiary. Id- at 70 (emphasis in original). The facts of the instant case are

clearly distinguishable from De Jesus, as the Plaintiffs’ amended complaint

17

Here, Plaintiffs’ allegations, far from merely stating general legal

conclusions, are well supported by factual assertions that sufficiently satisfy the

Rule 12(b)(6) (and, therefore, Rule 12(c)) standard. See Patel v. Contemporary

Classics of Beverly Hills, 259 F.3d 123, 126 (2d Cir. 2001) (citing Irish Lesbian &

Gav Org. v. Giuliani, 143 F.3d 638, 644 (2d Cir. 1998). Specifically, Plaintiffs’

amended complaint asserts that New York’s extensive history of intentional racial

discrimination against Blacks in voting dates back to its Constitution in 1777 and

spans more than a century. During this time, delegates to Constitutional

Conventions and legislators purposefully erected barriers, including requiring the

Legislature to enact a felon disqualification statute, that were intended to, and have

had the effect of, disfranchising Blacks and other racial minorities. Plaintiffs also

allege that without any adequate justification, New York disfranchises only those

persons with felony convictions who are incarcerated or on parole, but not those

persons convicted of felonies but given probation, a suspended or commuted

sentence, or other form of conditional or unconditional discharge.6 These facts,

specifically alleges facts and circumstances from which it can be inferred, without

much effort, that New York’s felon disfranchisement laws were enacted with intent

to disqualify Blacks from voting,

6 For ease of reference in the balance of this Brief we generally refer to such

alternate forms of sentence or disposition upon conviction of a felony as

“probation.”

18

taken as true, sufficiently state the basis for this Court to reverse the district court’s

ruling and remand this case for trial.

A. The District Court’s Premature Dismissal of Plaintiffs’

Amended Complaint is Contrary to the Law of this Circuit

and Supreme Court Precedent

While its uncertain which standard of review the district court may have

applied to Plaintiffs’ claims, it is clear that the district court failed to follow the

current precedent of the Supreme Court and this Circuit on pleading requirements.

The standard for evaluating Defendants’ motion for judgment on the pleadings

under Rule 12(c) is identical to that of a 12(b)(6) motion for failure to state a

claim. See Patel, 259 F.3d at 123. Thus, in deciding a Rule 12(c) motion, a court

must accept the allegations in the complaint as true and draw all reasonable

inferences in favor of the plaintiff. DeMuria v. Hawkes, 328 F.3d 704, 706 (2d

Cir. 2003) (citing Scutti Enters.. LLC v. Park Place Entm't Corn., 322 F.3d 211,

214 (2d Cir. 2003)); see also Williams v. Apfel, 204 F.3d 48,49 (2d Cir. 1999)).

In applying this liberal pleading standard, “[t]he court may not dismiss a

complaint unless it appears beyond doubt, even when the complaint is liberally

constmed, that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts which would entitle him to

relief.” DeMuria, 328 F.3d at 706. In addition, in considering a Rule 12(c)

motion, the court’s function “is merely to assess the legal feasibility of the

complaint, not to assay the weight of the evidence which might be offered in

19

support thereof.” Ryder Energy Distrib. Corp. v. Merrill Lynch Commodities,

Inc., 748 F.2d 774, 779 (2d Cir. 1984); Giesler v. Petrocelli, 616 F.2d 636, 639 (2d

Cir. 1980). In assessing the sufficiency of a pleading under Rule 12(c), “[t]he issue

is not whether a plaintiff will ultimately prevail but whether the claimant is entitled

to offer evidence to support the claims.” DeMuria, 328 F.3d at 706.

This Court requires that this already demanding standard for prevailing on a

Rule 12(c) motion be applied with “particular strictness when the plaintiff

complains of a civil rights violation.” Irish Lesbian & Gay Org„ 143 F.3d at 644;

see also Shechter v. Comptroller of New York, 79 F.3d 265, 270 (2d Cir. 1996);

fDwver v. Regan, 777 F.2d 825, 829 (2d Cir. 1985), modified on other grounds,

793 F.2d 457 (2d Cir. 1986)(same)).

In addition to the foregoing, courts must be mindful of the relatively low

standard and relaxed rules of pleading, which require a plaintiff to provide only a

“short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to

relief,” Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(a)(2), that “[a]ll pleadings shall be so constructed as to do

substantial justice.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(f)- Consistent with the spirit of Rule 8, this

Court has made clear that the Rule does not even require that a plaintiff plead all

relevant facts. Dioguardi v. Duming, 139 F.2d 774, 775 (2d Cir. 1944) (finding

that although plaintiff could not demonstrate precisely how medical tonics were

improperly disposed of, it was sufficient to plead that an impropriety had been

20

committed). Indeed, presentation of voluminous and/or specific evidence during

the pleading, rather than at the discovery phase, is not only unnecessary, but also

undesirable. See Nagler v. Admiral Corn., 248 F.2d 319, 326 (2d Cir. 1957).

In Swierkiewicz v. Sorema, N.A., 534 U.S. 506 (2002), the Supreme Court

unanimously rejected a heightened pleading standard upon the plaintiff. In

Swierkiewicz, a panel of this Court had affirmed the dismissal of the plaintiffs

lawsuit against his former employer on the grounds that his complaint did not

adequately allege facts constituting a prima facie case of racial discrimination

under the McDonnell Douglas7 standard. See 534 U.S. at 509-510. In reversing

the panel’s decision, the Supreme Court noted that a heightened pleading standard

in employment discrimination cases is inappropriate because “the prima facie case

under McDonnell Douglas . . . is an evidentiary standard, not a pleading

requirement.” Id. at 510.

The Supreme Court also held that a heightened pleading requirement

conflicted with Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a)(2), which provides that a

complaint must only include “a short and plain statement of the claim showing that

the pleader is entitled to relief.” Id at 512. Such a statement, the Supreme Court

reasoned, must simply “give the defendant fair notice of what the plaintiffs claim

is and the grounds upon which it rests.” Id (quoting Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S.

7 McDonnell Douglas Corn, v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 802 (1973).

21

41, 47 (1957)). Under this simplified pleading standard, “[a] court may dismiss a

complaint [under Rule 12] only if it is clear that no relief could be granted under

any set of facts that could be proved consistent with the allegations.” Id at 514.

Relying on the Supreme Court’s mling in Swierkiewicz, this Court in Phillip

v. University of Rochester, 316 F.3d 291, 298-99 (2d Cir. 2003), announced that it

would apply the lowered pleading standard set forth in Swierkiewicz. Indeed, even

before the Supreme Court’s ruling in Swierkiewicz, this Court had recognized that

“[w]hile clarity and precision are desirable in any pleading, the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure (F.R.C.P.) require little more than an indication of the type of

litigation that is involved. A generalized summary of the claims and defenses,

sufficient to afford fair notice to the parties is enough.” Friedlander v. Cimino, 520

F.2d 318, 319 (2d Cir. 1975) (citing Conley, 355 U.S. at 41, 47) (emphasis added).

Accordingly, this Court has acknowledged that dismissal on the pleadings is

reserved only for the cases in which “the complaint is so confused, ambiguous,

vague, or otherwise unintelligible that its true substance, if any, is well disguised.”

Salahuddin v. Cuomo, 861 F.2d 40, 42 (2d Cir. 1988).

The district court appears to have dismissed Plaintiffs’ amended complaint

for both failure to meet Rule 8(a)’s pleading requirements, and for failing to set

forth sufficient facts to state a legal claim. However, as set forth above, on either

22

ground, it is clear that the district court did not apply the appropriate standard of

review and its ruling should therefore be reversed.

II. Plaintiffs Met the Pleading Requirements of Rule 8(a) by Alleging

Facts that Put Defendants on Notice of Their Claims, and of Rule

12(c) by Setting Forth Sufficient Facts to State Legally Cognizable

Causes of Action

Notwithstanding the district court’s application of a heightened pleading

standard in the instant case, Plaintiffs’ amended complaint contains clear and

sufficient allegations of intentional discrimination and violations of equal

protection to withstand a dismissal at this stage of litigation. Far from asserting

conclusory allegations, the complaint is well supported by factual averments that

satisfy the Rule 12(c) standard. Plaintiffs’ amended complaint also clearly gave

Defendants fair notice of the basis for the claims and the grounds upon which the

claims rested and stated claims upon which relief could be granted.

As noted above, the principal goal of Rule 8(a), particularly the “short and

plain statement” requirement, is to guarantee that adverse parties receive notice of

legal actions to which they must respond. Salahuddin v. Cuomo, 861 F,2d at 42

(holding that a “statement should be plain because the principal function of

pleadings under the Federal Rules is to give the adverse party fair notice of the

claim asserted so as to enable him to answer and prepare for trial.”) (citing Geisler

v. Petrocelli, 616 F.2d at 640.. Plaintiffs’ amended complaint more than

adequately puts Defendants on notice that they are challenging the racial animus

23

behind the original enactment of felon disfranchisement laws in New York, as well

the equal protection violations inherent in a scheme that distinguishes among

individuals with felony convictions, denying the right to vote to those sentenced to

incarceration or serving parole, but not to those sentenced to probation. Likewise,

Plaintiffs set forth sufficient allegations to support a cognizable cause of action, as

required to survive a Rule 12(c) motion, and thus are “entitled to offer evidence to

support [their] claims.” DeMuria v. Hawkes. 328 F.3d at 706. The district court

erred in not allowing Plaintiffs to proceed to that stage.

Plaintiffs amended complaint contains numerous, specific allegations that

would support a complete review of the “circumstantial and direct evidence of

intent as may be available,” Vill. of Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hous. Dev. Corp.,

429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977), regarding the role of race in the enactment of felon

disfranchisement laws in New York. As detailed, infra, the complaint contains

allegations that the framers of New York law in the 18th and 19th centuries, both the

Legislature and the delegates to the various New York State Constitution

Conventions intended to, and did, discriminate against persons of color with

respect to the franchise and made “explicit statements of [their] intent” to that

effect. (JA 00106 [FAC 1 41]). The amended complaint sets forth the

unmistakable, de jure limitations on the ability of Black New Yorkers to vote? (JA

24

00106 [FAC f l 43-45]), that provided an historical context for the actions taken at

the 1821 New York Constitutional Convention.

Additionally, the amended complaint sufficiently alleges that these actions

had the discriminatory effect that the delegates had hoped for. For example, the

delegates remarked explicitly that Blacks were thirteen times more likely than

whites to be convicted of “infamous crime[s].” (JA 00107 [FAC 151]). Likewise,

Plaintiffs included allegations regarding the equal protection violations that occur

when the State discriminates among similarly situated individuals, denying the

right to vote to some individuals convicted of a felony conviction but not others,

and the racially disparate disfranchisement that results from this unequal

application of law. (JA 0012 [FAC f f 77-79]).

Accordingly, Plaintiffs’ amended complaint represents the very “short and

plain statement” contemplated by Rule 8(a), that would put any reader on notice

that the role of race in the initial adoption of felon disfranchisement laws in New

York is at the core of this case. Plaintiffs have also alleged sufficient facts setting

forth a cognizable claim of intentional discrimination which, under the standard for

assessing a Rule 12(c) Motion, allows them to proceed to discovery on these

claims. Finally, Plaintiffs have alleged sufficient facts to put Defendants on notice

of their race-neutral Equal Protection claim and to proceed to discovery on these

claims.

25

A. Intentional Discrimination Claim

The amended complaint sufficiently alleges that New York’s felon

disfranchisement laws were enacted with the intent to discriminate against

“persons incarcerated and on parole for a felony conviction . . . on account of their

race” in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth and the

Fifteenth Amendment. (JA 00113 [FAC fj[ 85-86]). In dismissing Plaintiffs’

intentional discrimination claim, the district court held that they did not allege any

facts to support a finding of intentional discrimination and referred to a subset of

the Plaintiffs’ allegations, which it said, even if tme, could not support a finding of

intentional discrimination. This conclusion is patently in error, not only because it

misstates the burden of pleading, but also because it fails to take into account the

breadth of allegations in the amended complaint.

1. Elements of an Intentional Discrimination Claim.

Although Plaintiffs are not required to state each element of an intentional

discrimination claim in order to survive a motion to dismiss or for judgment on the

pleadings, it is useful nonetheless to understand the scope of such a claim in order

to appreciate the extent to which Plaintiffs’ claim of intentional discrimination

easily satisfies the requirements of Rule 8(a) and 12(c). In Richardson v. Ramirez,

418 U.S. 24 (1974), the Supreme Court held that § 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment

allows states to exclude from the franchise convicted felons, notwithstanding § l ’s

26

requirement that “[n]o state shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the

equal protection of the laws.” U.S. Const, amend. XIV, § 1.

Richardson did not, however, close the door on all Constitutional challenges

to felon disfranchisement provisions; indeed it did not even close the door on

Equal Protection challenges. Nearly a decade after deciding Richardson, the Court

in Hunter v. Underwood. 471 U.S. 222 (1985), found that Alabama had enacted its

felon disfranchisement provision with discriminatory intent, and therefore in

violation of the Equal Protection Clause, on grounds that § 2’s authorization of

state disfranchisement laws did not permit purposeful discrimination. Hunter, 471

U.S. at 233. Hunter, therefore, stands for the proposition that racially motivated

disfranchisement statutes violate the Equal Protection Clause even if Richardson

otherwise sanctions such laws (not adopted with discriminatory' intent) under the

Fourteenth Amendment. Id. at 232-33.

Facially neutral state laws that have a racially disparate impact, like New

York’s felon disfranchisement laws, are subject to the test outlined in Arlington

Heights in order to determine whether such laws violate the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. See Hunter, 471 U.S. at 228. In Arlington

Heights, the Supreme Court held that although “[disproportionate impact is not

irrelevant,” proof of “racially discriminatory intent or purpose is required to show a

violation of the Equal Protection Clause.” 429 U.S. at 264-265 (quoting

27

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 242 (1976)), Indeed, determining whether

invidious discriminatory purpose was a motivating factor behind an official action

“demands a sensitive inquiry into such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent

as may be available.” Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266. Accordingly, as

evidence of intent courts may consider, among other things, whether the impact of

an action bears more heavily on one race than another, the historical background of

an official decision, and the legislative or administrative history of an official

action, particularly where there are statements by members of the decision-making

body. See id. at 266-67.

2. The District Court Incorrectly Applied the Pleading

Standard and Mischaracterized the Allegations in the

Amended Complaint.

The district court provided a handful of cursory and conclusory reasons for

dismissing Plaintiffs’ intentional discrimination claim, which are addressed in turn.

First, the district court took in isolation certain allegations concerning New

York State’s history of discrimination in voting, stating that “just because some

laws were enacted in the early to mid-1800s with the intent to discriminate against

blacks and other minorities does not necessarily mean that New York Constitution

Article II, § 3 and § 5-106(2) or their predecessors were similarly enacted with

such intent.” (JA 00019 [00 Civ. 8586 (Mem. & Order, at 8)]). The district court’s

28

reasoning in this instance is a clear example of its misapplication of the pleading

standard.

To substantiate the allegations in the amended complaint that an invidious

racial purpose was a motivating factor in the enactment of New York’s felon

voting restrictions, Plaintiffs utilized the available historical background and

legislative history of the restrictions, (JA 00105-109 [FAC Hf 39-60]), and their

disproportionate impact on Blacks and Latinos. (JA 00109-00111 [FAC f f 61-

71]). However, the district court failed to read Plaintiffs’ allegations in the light

most favorable to them, as is indicated by the court’s determination that such

history “does not necessarily” signify the state’s intent to discriminate through its

felon disfranchisement laws. This is plainly the wrong standard. The question is

not whether past racial discrimination in voting “necessarily” means that New

York’s felon disfranchisement laws were enacted with the intent to discriminate.

Rather, the question is whether such allegations, which include facts concerning

the enactment of the felon disfranchisement statute specifically, could support such

a finding or entitle Plaintiffs to “offer evidence in support” of a finding that they

were enacted for that purpose. Swierkiewicz v. Sorema N.A., 534 U.S. 506, 511

(2002) (quoting Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232, 236 (1974), overruled on other

grounds. Davis v. Scherer, 468 U.S. 183 (1984)); see also DeMuria v. Hawkes, 328

F.3d at 706. The answer in this case is in the affirmative.

29

Arlington Heights holds that proof of intent to discriminate can be derived

from a contextual analysis of a variety of factors that collectively support an

inference of racial animus. 429 U.S. at 266 (finding that “whether invidious

discriminatory purpose was a motivating factor demands a sensitive inquiry into

such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent as may be available.”). This

analysis would include examining allegations such as Plaintiffs’ assertions that

African Americans were routinely intentionally denied suffrage on an equal basis

as Whites, (JA 00105-107 [FAC f f 39-50]), openly regarded and referred to as

being unfit for suffrage, (JA 00106-107 [FACf][ 46, 51]), and described as being

13 times as likely as Whites to commit infamous crimes, (JA 00107 [FAC 151])

and that, “two years after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, an

unprecedented committee convened and amended the disfranchisement provision

of the New York Constitution to require the state legislature, at its following

session, to enact laws excluding person convicted of infamous crimes from the

right to vote . . . . Theretofore, the enactment of such laws was permissive.” (JA

00108 [FAC 156]).

Plaintiffs further alleged that the present-day impact of New York’s felon

disfranchisement laws has the intended effect of denying the franchise to Blacks

and Latinos in numbers vastly disproportionate to Whites. Specifically, Plaintiffs

alleged that Blacks and Latinos are sentenced to incarceration at substantially

30

higher rates than Whites, and Whites are sentenced to probation at substantially

higher rates than Blacks and Latinos. (JA 00110 [FAC f 66]). Collectively,

Blacks and Latinos make up 86% of the total current prison population and 82% of

the total current parolee population in New York State, while they approximate

only 31% of New York’s overall population. (JA 00110 [FAC ][ 64]). As a result,

nearly 52% of those currently denied the right to vote pursuant to New York State

Election Law § 5-106(2) are Black and nearly 35% are Latino. Id. at f 68.

Collectively, Blacks and Latinos comprise nearly 87% of those currently denied

the right to vote pursuant to New York State Election Law § 5-106(2). Id.

Arlington Heights requires an evaluation of these factors as a whole, in order

to appreciate the full context of the origin and effect of the laws in question, and

not in isolation as the district court did here. (JA 00019-20 [Mem. & Order 00 Civ

8586, at 8-9]). The district court specifically addressed only “this one allegation”

of Plaintiffs, that Blacks are 13 times more likely to commit a crime than Whites,

and found it insufficient to state a claim for intentional discrimination. Id.

When read together in the light most favorable to the Plaintiffs, the

allegations in the amended complaint tell a persuasive story of a pattern of

historical intentional discrimination in voting, including repeated explicit

statements about Blacks’ fitness for suffrage, their perceived criminality, and the

codification of mandatory disfranchisement during an unprecedented special

31

session at a time when overt denial of the franchise to African Americans was

newly outlawed by the Fifteenth Amendment. These allegations are more than

sufficient to notify Defendants of the claims lodged against them and are not meant

or required to be exhaustive of all knowledge or evidence in Plaintiffs’ possession.

Finally, the district court attempted to compare the allegations in the

amended complaint to the evidence presented in Flunter after the plaintiffs in that

litigation had the benefit of discovery and a trial on the merits. Even in making

this inappropriate comparison for purposes of a 12(c) motion, the district court

failed to recognize the actual similarities in the facts alleged in the instant case and

those proven in Hunter. The district court notes that in Hunter:

[T]he plaintiffs in Hunter provided strong factual support showing a

long history of racial discrimination including actual testimony of

specific discriminatory statements made during the 1901

Constitutional Convention where a “zeal for white supremacy ran

rampant.” Here, plaintiffs have not alleged any such facts with

respect to the enactment of New York Constitution Article II, § 4 and

§ 5-106(2) or their predecessors.

(JA 00020 [Mem. & Order 008586, at 9 n.3]) (citations omitted).

On the contrary, Plaintiffs’ amended complaint asserts throughout that New

York’s extensive history of intentional racial discrimination in voting dates as far

back as New York’s Constitution in 1777 and spans more than 100 years, during

which time delegates to Constitutional Conventions and legislators purposefully

erected barriers intended to prevent Blacks from voting, (culminating in the

32

required enactment of a felon disqualification statute), that were intended to, and

have had the effect of, disproportionately disfranchising Blacks and other racial

minorities. (JA 00106-108 [FAC f f 41-42, 43-46, 51-52, 57]). These allegations,

taken as true, sufficiently state the basis for this Court to find a violation of the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Fifteenth

Amendment.

The allegations contained in the amended complaint are, in fact, more

detailed and specific than those contained in the complaint in Hunter. In Hunter,

the Supreme Court relied on a number of historical factors presented to the District

Court as evidence of Alabama’s discriminatory intent, including the racial

composition of members of the convention that enacted the bill, comments made

by the President of the convention, historical studies noting that the Alabama

convention was part of a movement to disfranchise Blacks, evidence that the

crimes selected for inclusion in the provision were more commonly committed by

Blacks, and witness testimony that the provision had an immediate and predictable

disparate impact on Black voters. Hunter, 471 U.S at 224-30. Although these

factors were enumerated as evidence of discriminatory intent by both the Supreme

Court in Hunter and the 11th Circuit, Underwood v. Hunter, 730 F.2d 614 (11th Cir.

1984), aff’d 471 U.S. 222 (1985), none of these factors was mentioned in the

33

original complaint filed by plaintiffs in the case. See Compl., Underwood v.

Hunter. No. CA-78-Mo704S (N.D. Ala., filed June 21, 1978).8

By contrast, the amended complaint in this case reveals a historical pattern

of discrimination by New York intended to disfranchise Black voters. (JA 00105-

108 [FAC f]l 39-57]). The historical development of New York’s felon

disfranchisement laws in the amended compliant is not embodied in merely one

comment made at one convention, but rather is a culmination of specific efforts

aimed at disfranchising Blacks that spanned the course of more than 100 years.

(JA 00106-108 [FAC f f 43, 45-46, 51-52, 57]). As a result, Plaintiffs’ amended

complaint clearly alleges Equal Protection and Fifteenth Amendment claims

consistent with the Supreme Court’s holding in Hunter. Finally, the issue is not

whether Plaintiffs will ultimately prevail, but whether Plaintiffs are entitled to offer

evidence to support the claims in the amended complaint. See Swierkiewicz, 534

U.S. at 511. Thus, Plaintiffs are not required to produce evidence, direct or

otherwise, or necessarily allege facts identical to those in Hunter as the district

court suggests. Rather, Plaintiffs are required to, and indeed do, sufficiently allege

g

It is important to note here, however, that this is evidence that must be

developed through discovery, including expert testimony, and was not required

to be proven or alleged in exhaustive detail by plaintiffs at the stage of the

litigation in which the complaint was dismissed. Plaintiffs-appellants should

be afforded an opportunity to develop their case as plaintiffs were in Hunter.

(JA 00033-35).

34

that New York practiced unlawful discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments and the Supreme Court’s rulings in Arlington Heights and

Hunter.9

B. Applying Rational Basis Review in a Wholly Deferential Manner, the

District Court Dismissed Plaintiffs’ Claim that New York State’s

Non-Uniform Felon Disfranchisement Scheme Violates Equal

Protection Guarantees Prior to Affording Plaintiffs the Opportunity

to Develop and Present Evidence Regarding Defendants’

Justifications for the Law.

In addition to an intentional race discrimination claim, Plaintiffs assert that

§5-106(2)’s felon disfranchisement scheme violates equal protection guarantees

because it distinguishes among felons, denying the right to vote only to those

felons sentenced to incarceration or serving parole, and not to those sentenced to

probation. The district court erred in dismissing these claims at the pleading stage,

without subjecting the distinction to strict scrutiny review, and without providing

Plaintiffs an opportunity to prove that no rational basis is served by the felon

disfranchisement scheme.

9 As noted above, although Rule 12(c) does not require plaintiffs at this stage

of the litigation to provide an exhaustive history of New York’s intentional

discrimination against Blacks, and the allegations contained in the amended

complaint sufficiently state the basis for this Court to find a violation of the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Fifteenth

Amendment, plaintiffs here provide additional historical information to

highlight the context in which New York’s felon disfranchisement laws were

enacted.

35

As a threshold matter, Plaintiffs meet Rule 8(a)’s pleading standard for

alleging an equal protection claim. Plaintiffs allege that, as a result of New York’s

felon disfranchisement scheme, persons who are convicted of “bribery or of any

infamous crime” and are sentenced to incarceration and/or parole are not permitted

to vote, whereas their counterparts who have been pardoned, received a suspended

or commuted sentence or been sentenced to probation or conditional or

unconditional discharge are permitted to vote. (JA 00109 [FAC 1 58-59]). In

addition to allegations regarding the racial animus underlying the felon

disfranchisement scheme, (JA 00105-108 [FAC fj[ 38-56]), Plaintiffs’ amended

complaint contains allegations that this distinction described above has a racially

disproportionate impact on Blacks and Latinos, who are prosecuted, convicted and

sentenced to incarceration at rates vastly disproportionate to Whites. (JA 00109-

110 [FAC f|[ 60-67]). Thus, Plaintiffs sufficiently state an equal protection claim.

See DeMuria, 328 F.3d at 707 (finding that allegations of impermissible motive

and animus is sufficient to allow plaintiffs to proceed with equal protection claim

“at this earliest stage of the proceedings”). The court nevertheless dismissed

Plaintiffs’ claims, applying the incorrect standard of review and prohibiting

Plaintiffs from presenting any evidence to counter the purported justification for

the felon disfranchisement scheme.

36

1. The district court erred in dismissing Plaintiffs’ equal

protection claims without subjecting §5-106 to strict

scrutiny.

The Equal Protection Clause requires that all persons who are similarly

situated be treated alike. City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr., Inc., 473 U.S.

432, 439 (1985). The “threshold question” in an equal protection challenge “is the

appropriate level of scrutiny to be applied.” Beniamin v. Jacobson, 124 F.3d 162,

174 (2d Cir. 1997). In addressing this “threshold question,” the Supreme Court has

held that a statute is subject to “heightened scrutiny” when it “burdens [a]

fundamental right.” Id. Here, as Plaintiffs alleged in their amended complaint,

New York’s felon disfranchisement scheme strips individuals who are convicted of

a felony and sentenced to incarceration or parole of the right to vote, while leaving

the voting rights of those sentenced to probation intact. (JA 00109 [FAC 1 58-

59]). Because it severely burdens the fundamental right to vote of one class of

individuals with felony convictions, the statute must be strictly scrutinized. See

Kramer v. Union Free Sch. Dist. No. 15. 395 U.S. 621, 626-27 (1969) (“If a

challenged state statute grants the right to vote to some bona fide residents of

requisite age and citizenship and denies the franchise to others, the Court

must determine whether the exclusions are necessary to promote a compelling state

interest.”). In dismissing Plaintiffs’ equal protection claim, the district court

applied a deferential standard wholly inconsistent with this heightened scrutiny

37

requirement, thereby failing to perform its own searching analysis of Defendants’

asserted justification for the voting ban. And, by dismissing Plaintiffs’ claim at

this stage of litigation, the court denied Plaintiffs the opportunity to develop and

present such an analysis to the court as well.

As the Supreme Court has stated, “voting is of the most fundamental

significance under our constitutional structure.” Burdick v. Takushi, 504 U.S. 428,

433 (1992), see also Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 562 (1964) (stating that, by

denying some citizens the right to vote, durational residence requirements deprive

them of a “fundamental political right, . . . preservative of all rights.”) (quoting

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370 (1886)). When Fourteenth Amendment

rights are “subjected to ‘severe’ restrictions, the regulation must be ‘narrowly

drawn to advance a state interest of compelling importance.”’ Burdick, 504 U.S. at

434 (1992) (quoting Norman v. Reed, 502 U.S. 279, 289 (1992)); see also Dunn v.

Blumstein, 405 U.S. 330, 336 (1972) (stating that “before the right [to vote] can be

restricted, the purpose of the restriction and the asserted overriding interests served

by it must meet close constitutional scrutiny”). A heightened standard of review is

applicable in this case because New York’s felon disfranchisement scheme directly

deprives Plaintiffs’ of their fundamental right to vote, and indeed denies the right

to vote to felons who are incarcerated or on parole, while preserving the voting

rights of individuals convicted of similar offenses yet sentenced to probation.

38

To perform this rigorous inquiry, the court was required to examine the

propriety of New York’s felon disqualification statute and sustain it only if it

concluded that the statute is drawn narrowly to advance a compelling New York

State interest. Burdick, 504 U.S. at 434. Yet, the district court did no such thing.

Rather, in dismissing Plaintiffs’ equal protection claims, the district court found

that New York’s non-uniform scheme of disfranchising only those felons

sentenced to incarceration or serving parole met the deferential standard of

“rational, not arbitrary.” Hayden v. Pataki, No. 00 Civ. 8586, at *10 (quoting

Williams v. Taylor, 677 F.2d 510, 516 (5th Cir. 1982)). The court simply accepted

Defendants’ explanation for the legislature’s 1973 amendment, namely, that the

amendment helped to make consistent the statutory scheme. Id Moreover, going

beyond the Defendants’ articulated rationale, the district court consulted Black’s

Law Dictionary for the definitions of parole and probation to conclude that

denying suffrage to one group and not the other “is certainly not arbitrary.” (JA

00022 [00 Civ. 8586 Mem. & Order, at 11]). Thus, the district court did no

searching review of justifications for the felon disfranchisement scheme. And in

dismissing the Plaintiffs’ claims at this early stage of the litigation, the Court

denied Plaintiffs the opportunity to inquire into Defendants’ justification, as well.

39

2. Even if Rational Basis is the Appropriate Level of Review

for Plaintiffs’ Equal Protection Claims, the District Court

Erred in Applying the Standard in a Wholly Deferential

Manner and Finding a Rational Basis for New York’s Felon

Disfranchisement Regime.

In addition and in the alternative, the district court should have applied

rational basis review with some analysis of Defendants’ asserted justification for

the felon disfranchisement scheme, and only after providing Plaintiffs with the

opportunity to present evidence to counter that justification. Specifically, the court

should have looked beyond Defendants’ articulated justifications when

determining whether the felon disfranchisement scheme, which in some cases

results in a lifetime ban on voting, is rational. At the very least, the Court should

have provided Plaintiffs with the opportunity to develop and provide its own

evidence regarding the purposes served by the law.

As the Supreme Court noted in Romer v. Evans, even when applying

rational basis review, courts can “insist on knowing the relation between the

classification adopted and the object to be attained.” 517 U.S. 620, 632 (1996).

This “search for the link between classification and objective gives substance to

the Equal Protection Clause.” IcL Indeed, “[b]y requiring that the classification

bear a rational relationship to an independent and legitimate legislative end, we

ensure that classifications are not drawn for the purpose of disadvantaging the

group burdened by the law.” IdL

40

In Romer, the Court examined the constitutionality of an amendment to the

Colorado state constitution which effectively repealed state and local provisions

barring discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Applying a rational basis

level of the review, the court nonetheless found that the provision was “at once too

narrow and too broad. It identifies persons by a single trait and then denies them

protection across the board.” Id. at 633.10

Here, by disfranchising individuals who are convicted of a felony and