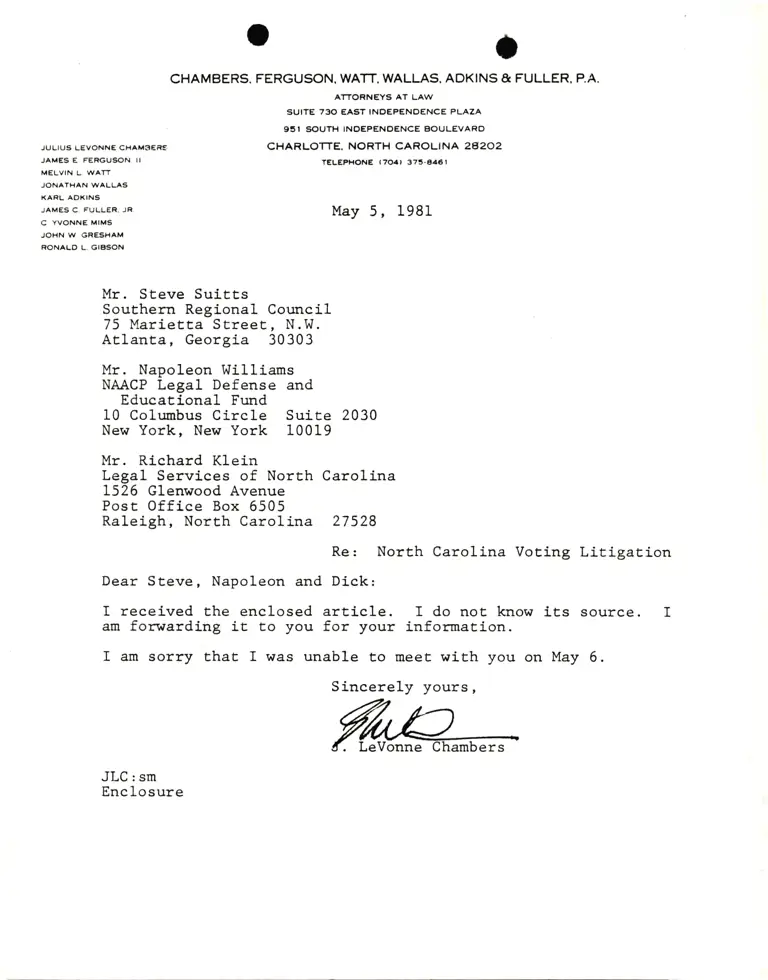

Correspondence from Chambers to Suitts, Williams, and Klein

Correspondence

May 5, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. Correspondence from Chambers to Suitts, Williams, and Klein, 1981. 3fafb6d0-d992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8997ee9e-d44d-4c10-be5e-1547399eadb6/correspondence-from-chambers-to-suitts-williams-and-klein. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

CHAMBERS, FERGUSON, WATT, WALLAS, ADKI

a

NS & FULLER. P.A.

JULIUS LEVONN€ CHAMS€RS

JAMES E FERGUSON II

MELVIN L WATT

JONATHAN WALLAS

KARL AOKINS

JAMES C. FULLER. JN

C YVONN€ MIMS

JOHN W. GRESHAM

RONALO L, GIBSON

ATTORNEYS AT LA\^/

SUITE 73O EAST INDEPENOENCE PLAZA

95I SOUTH INOEPENOENCE BOULEVARD

CHARLOTTE. NORTH CAROLINA 25202

May 5, 1981

Mr. Steve SuiEts

Southern Regional Cor:nciL

75 Marietta StreeE, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Mr. Napoleon Williams

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fr:nd

10 Coh:mbus Circle Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Mr. Richard Klein

Legal Services of North Carolina

L526 Glenwood Avenue

Post Office Box 6505

Raleigh, North Carolina 27528

Re: North Carolina Voting Litigation

Dear Steve, Napoleon and Dick:

I received the enclosed article. I do not know its

am fonrarding it to you for your information.

I am sorry that I was unable Eo meet with you on May

JLC: sm

Enclosure

source. I

6.

Sincerely yours,

LeVonne