Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Opinion

Public Court Documents

February 29, 1988 - June 15, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Opinion, 1988. fe0e37d7-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/89ad8ac5-3b4c-4a1a-91e5-364db12651e3/patterson-v-mclean-credit-union-opinion. Accessed February 13, 2026.

Copied!

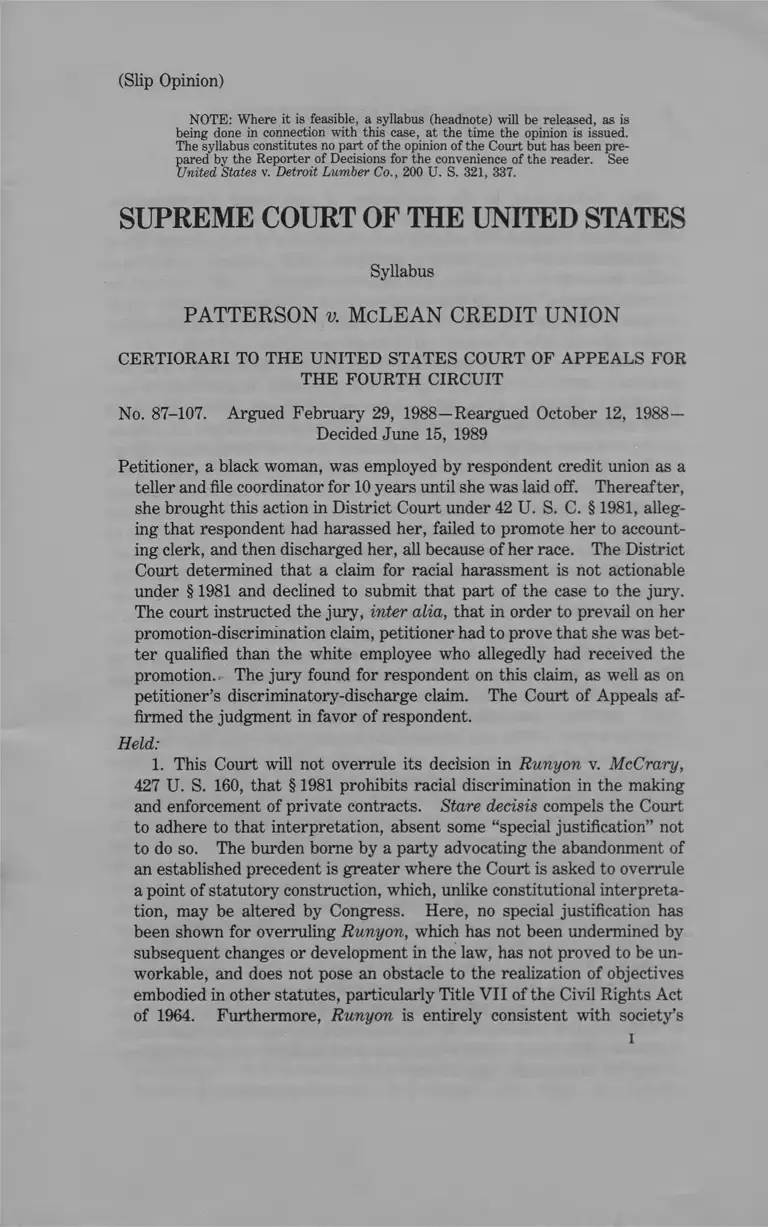

(Slip Opinion)

NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is

being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued.

The syllabus constitutes no part o f the opinion o f the Court but has been pre

pared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See

United States v. Detroit Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-107. Argued February 29, 1988—Reargued October 12, 1988—

Decided June 15, 1989

Petitioner, a black woman, was employed by respondent credit union as a

teller and file coordinator for 10 years until she was laid off. Thereafter,

she brought this action in District Court under 42 U. S. C. § 1981, alleg

ing that respondent had harassed her, failed to promote her to account

ing clerk, and then discharged her, all because of her race. The District

Court determined that a claim for racial harassment is not actionable

under § 1981 and declined to submit that part of the case to the jury.

The court instructed the jury, inter alia, that in order to prevail on her

promotion-discrimination claim, petitioner had to prove that she was bet

ter qualified than the white employee who allegedly had received the

promotion.. The jury found for respondent on this claim, as well as on

petitioner’s discriminatory-discharge claim. The Court of Appeals af

firmed the judgment in favor of respondent.

Held:

1. This Court will not overrule its decision in Runyon v. McCrary,

427 U. S. 160, that § 1981 prohibits racial discrimination in the making

and enforcement of private contracts. Stare decisis compels the Court

to adhere to that interpretation, absent some “special justification” not

to do so. The burden borne by a party advocating the abandonment of

an established precedent is greater where the Court is asked to overrule

a point of statutory construction, which, unlike constitutional interpreta

tion, may be altered by Congress. Here, no special justification has

been shown for overruling Runyon, which has not been undermined by

subsequent changes or development in the law, has not proved to be un

workable, and does not pose an obstacle to the realization of objectives

embodied in other statutes, particularly Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. Furthermore, Runyon is entirely consistent with society’s

I

II PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

Syllabus

deep commitment to the eradication of race-based discrimination.

Pp.3-6.

2. Racial harassment relating to the conditions of employment is not

actionable under § 1981, which provides that “[a]ll persons . . . shall have

the same right . . . to make and enforce contracts . . . as is enjoyed by

white citizens,” because that provision does not apply to conduct which

occurs after the formation of a contract and which does not interfere with

the right to enforce established contract obligations. Pp. 7-14.

(a) Since § 1981 is restricted in its scope to forbidding racial dis

crimination in the “making[ing] and enforce[ment]” of contracts, it can

not be construed as a general proscription of discrimination in all aspects

of contract relations. It provides no relief where an alleged discrimina

tory act does not involve the impairment of one of the specified rights.

The “right. . . to make . . . contracts” extends only to the formation of a

contract, such that § 1981’s prohibition encompasses the discriminatory

refusal to enter into a contract with someone, as well as the offer to make

a contract only on discriminatory terms. That right does not extend to

conduct by the employer after the contract relation has been established,

including breach of the contract’s terms or the imposition of discrimina

tory working conditions. The “right. . . to . . . enforce contracts” em

braces only protection of a judicial or nonjudicial legal process, and of a

right of access to that process, that will address and resolve contract-law

claims without regard to race. It does not extend beyond conduct by an

employer which impairs an employee’s ability to enforce through legal

process his or her established contract rights. Pp. 7-10.

(b) Thus, petitioner’s racial harassment claim is not actionable

under § 1981. With the possible exception of her claim that respond

ent’s refusal to promote her was discriminatory, none of the conduct

which she alleges —that her supervisor periodically stared at her for min

utes at a time, gave her more work than white employees, assigned her

to demeaning tasks not given to white employees, subjected her to a ra

cial slur, and singled her out for criticism, and that she was not afforded

training for higher level jobs and was denied wage increases—involves

either a refusal to make a contract with her or her ability to enforce her

established contract rights. Rather, the conduct alleged is postforma

tion conduct by the employer relating to the terms and conditions of con

tinuing employment, which is actionable only under the more expansive

reach of Title VII. Interpreting § 1981 to cover postformation conduct

unrelated to an employee’s right to enforce her contract is not only incon

sistent with the statute’s limitations, but also would undermine Title

VII’s detailed procedures for the administrative conciliation and resolu

tion of claims, since § 1981 requires no administrative review or opportu

nity for conciliation. Pp. 10-14.

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION hi

Syllabus

(c) There is no merit to the contention that § 1981’s “same right”

phrase must be interpreted to incorporate state contract law, such that

racial harassment in the conditions of employment is actionable when,

and only when, it amounts to a breach of contract under state law. That

theory contradicts Runyon by assuming that § 1981’s prohibitions are

limited to state-law protections. Moreover, racial harassment amount

ing to breach of contract, like racial harassment alone, impairs neither

the right to make nor the right to enforce a contract. In addition, the

theory would unjustifiably federalize all state-law breach of contract

claims where racial animus is alleged, since § 1981 covers all types of con

tracts. Also without merit is the argument that § 1981 should be inter

preted to reach racial harassment that is sufficiently “severe or perva

sive” as effectively to belie any claim that the contract was entered into

in a racially neutral manner. Although racial harassment may be used

as evidence that a divergence in the explicit terms of particular contracts

is explained by racial animus, the amorphous and manipulable “severe or

pervasive” standard cannot be used to transform a nonactionable chal

lenge to employment conditions into a viable challenge to the employer’s

refusal to contract. Pp. 14-16.

3. The District Court erred when it instructed the jury that petitioner

had to prove that she was better qualified than the white employee who

allegedly received the accounting clerk promotion. Pp. 16-20.

(a) Discriminatory promotion claims are actionable under §1981

only where the promotion rises to the level of an opportunity for a new

and distinct relation between the employer and the employee. Here,

respondent has never argued that petitioner’s promotion claim is not

cognizable under § 1981. Pp. 16-17.

(b) The Title VII disparate-treatment framework of proof applies to

claims of racial discrimination under § 1981. Thus, to make out a prima

facie case, petitioner need only prove by a preponderance of the evidence

that she applied for and was qualified for an available position, that she

was rejected, and that the employer then either continued to seek appli

cants for the position, or, as is alleged here, filled the position with a

white employee. The establishment of a prima facie case creates an in

ference of discrimination, which the employer may rebut by articulating

a legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for its action. Here, respondent

did so by presenting evidence that it promoted the white applicant be

cause she was better qualified for the job. Thereafter, however, peti

tioner should have had the opportunity to demonstrate that respondent’s

proffered reasons for its decision were not its true reasons. There are a

variety of types of evidence that an employee can introduce to show that

an employer’s stated reasons are pretextual, and the plaintiff may not be

limited to presenting evidence of a certain type. Thus, the District

IV PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

Syllabus

Court erred in instructing the jury that petitioner could carry her bur

den of persuasion only by showing that she was in fact better qualified

than the person who got the job. Pp. 17-20.

805 F. 2d 1143, affirmed in part, vacated in part, and remanded.

K e n n e d y , J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which R e h n q u i s t ,

C. J., and W h i t e , O ’ C o n n o r , and S c a l i a , JJ., joined. B r e n n a n , J.,

filed an opinion concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part,

in which M a r s h a l l and B l a c k m u n , JJ., joined, and in Parts I I - B , II-C,

and III of which S t e v e n s , J., joined. S t e v e n s , J., filed an opinion con

curring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part.

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the

preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are requested to

notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the United States, Wash

ington, D. C. 20543, of any typographical or other formal errors, in order

that corrections may be made before the preliminary print goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 87-107

BRENDA PATTERSON, PETITIONER v.

McLEAN CREDIT UNION

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

[June 15, 1989]

J u s t ic e K e n n e d y delivered the opinion of the Court.

In this case, we consider important issues respecting the

meaning and coverage of one of our oldest civil rights stat

utes, 42 U. S. C. § 1981.

I

Petitioner Brenda Patterson, a black woman, was em

ployed by respondent McLean Credit Union as a teller and a

file coordinator, commencing in May 1972. In July 1982, she

was laid off. After the termination, petitioner commenced

this action in District Court. She alleged that respondent, in

violation of 42 U. S. C. § 1981, had harassed her, failed to

promote her to an intermediate accounting clerk position, and

then discharged her, all because of her race. Petitioner also

claimed this conduct amounted to an intentional infliction of

emotional distress, actionable under North Carolina tort law.

The District Court determined that a claim for racial ha

rassment is not actionable under § 1981 and declined to sub

mit that part of the case to the jury. The jury did receive

and deliberate upon petitioner’s § 1981 claims based on al

leged discrimination in her discharge and the failure to pro

mote her, and it found for respondent on both claims. As for

petitioner’s state law claim, the District Court directed a

verdict for respondent on the ground that the employer’s con

duct did not rise to the level of outrageousness required to

2 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

state a claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress

under applicable standards of North Carolina law.

In the Court of Appeals, petitioner raised two matters

which are relevant here. First, she challenged the District

Court’s refusal to submit to the jury her § 1981 claim based

on racial harassment. Second, she argued that the District

Court erred in instructing the jury that in order to prevail

on her § 1981 claim of discriminatory failure to promote,

she must show that she was better qualified than the white

employee who she alleges was promoted in her stead. The

Court of Appeals affirmed. 805 F. 2d 1143 (1986). On the

racial harassment issue, the court held that while instances of

racial harassment “may implicate the terms and conditions of

employment under Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U. S. C. §2000e,] and of course may be probative of the

discriminatory intent required to be shown in a § 1981 ac

tion,” id., at 1145 (citation omitted), racial harassment itself

is not cognizable under §1981 because “racial harassment

does not abridge the right to ‘make’ and ‘enforce’ contracts,”

id., at 1146. On the jury instruction issue, the court held

that once respondent had advanced superior qualification as a

legitimate nondiscriminatory reason for its promotion deci

sion, petitioner had the burden of persuasion to show that re

spondent’s justification was a pretext and that she was better

qualified than the employee who was chosen for the job. Id.,

at 1147.

We granted certiorari to decide whether petitioner’s claim

of racial harassment in her employment is actionable under

§1981, and whether the jury instruction given by the Dis

trict Court on petitioner’s § 1981 promotion claim was error.

484 U. S. 814 (1987). After oral argument on these issues,

we requested the parties to brief and argue an additional

question:

“Whether or not the interpretation of 42 U. S. C.

§ 1981 adopted by this Court in Runyon v. McCrary, 427

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 3

U. S. 160 (1976), should be reconsidered.” 485 U. S.

617 (1988).

We now decline to overrule our decision in Runyon v. Mc

Crary, 427 U. S. 160 (1976). We hold further that racial

harassment relating to the conditions of employment is not

actionable under § 1981 because that provision does not apply

to conduct which occurs after the formation of a contract and

which does not interfere with the right to enforce established

contract obligations. Finally, we hold that the District

Court erred in instructing the jury regarding petitioner’s

burden in proving her discriminatory promotion claim.

II

In Runyon, the Court considered whether § 1981 prohibits

private schools from excluding children who are qualified for

admission, solely on the basis of race. We held that § 1981

did prohibit such conduct, noting that it was already well

established in prior decisions that §1981 “prohibits racial

discrimination in the making and enforcement of private

contracts.” Id., at 168, citing Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency, Inc., 421 U. S. 454, 459-460 (1975); Tillman v.

Wheaton-Haven Recreation Assn., Inc., 410 U. S. 431, 439-

440 (1973). The arguments about whether Runyon was de

cided correctly in light of the language and history of the stat

ute were examined and discussed with great care in our deci

sion. It was recognized at the time that a strong case could

be made for the view that the statute does not reach private

conduct, see 427 U. S., at 186 (Powell, J., concurring); id., at

189 (S t e v e n s , J., concurring); id., at 192 (W h i t e , J., dis

senting), but that view did not prevail. Some Members of

this Court believe that Runyon was decided incorrectly, and

others consider it correct on its own footing, but the question

before us is whether it ought now to be overturned. We con

clude after reargument that Runyon should not be overruled,

and we now reaffirm that § 1981 prohibits racial discrimina

tion in the making and enforcement of private contracts.

4 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

The Court has said often and with great emphasis that

“the doctrine of stare decisis is of fundamental importance to

the rule of law.” Welch v. Texas Dept, of Highways and

Public Transportation, 483 U. S. 468, 494 (1987). Although

we have cautioned that “stare decisis is a principle of policy

and not a mechanical formula of adherence to the latest deci

sion,” Boys Markets, Inc. v. Retail Clerks, 398 U. S. 235,

241 (1970), it is indisputable that stare decisis is a basic self-

governing principle within the Judicial Branch, which is en

trusted with the sensitive and difficult task of fashioning and

preserving a jurisprudential system that is not based upon

“an arbitrary discretion.” The Federalist, No. 78, p. 490

(H. Lodge ed. 1888) (A. Hamilton). See also Vasquez v.

Hillery, 474 U. S. 254, 265 (1986) (stare decisis ensures that

“the law will not merely change erratically” and “permits

society to presume that bedrock principles are founded in the

law rather than in the proclivities of individuals”).

Our precedents are not sacrosanct, for we have overruled

prior decisions where the necessity and propriety of doing

so has been established. See Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union, 485 U. S. 617, 617-618 (1988) (citing cases). None

theless, we have held that “any departure from the doctrine

of stare decisis demands special justification.” Arizona v.

Rumsey, 467 U. S. 203, 212 (1984). We have said also that

the burden borne by the party advocating the abandonment

of an established precedent is greater where the Court is

asked to overrule a point of statutory construction. Consid

erations of stare decisis have special force in the area of stat

utory interpretation, for here, unlike in the context of con

stitutional interpretation, the legislative power is implicated,

and Congress remains free to alter what we have done. See,

e. g ., Square D Co. v. Niagara Frontier Tariff Bureau, Inc.,

476 U. S. 409, 424 (1986); Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431

U. S. 720, 736 (1977).

We conclude, upon direct consideration of the issue, that

no special justification has been shown for overruling Run

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 5

yon. In cases where statutory precedents have been over

ruled, the primary reason for the Court’s shift in position has

been the intervening development of the law, through either

the growth of judicial doctrine or further action taken by

Congress. Where such changes have removed or weakened

the conceptual underpinnings from the prior decision, see,

e. g., Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson /American Express,

Inc., 490 U. S. ------ , ------ (1989); Andrews v. Louisville &

Nashville R. Co., 406 U. S. 320, 322-323 (1972), or where the

later law has rendered the decision irreconcilable with com

peting legal doctrines or policies, see, e. g., Braden v. 30th

Judicial Circuit Ct. of Ky., 410 U. S. 484, 497-499 (1973);

Construction Laborers v. Curry, 371 U. S. 542, 552 (1963),

the Court has not hesitated to overrule an earlier decision.

Our decision in Runyon has not been undermined by subse

quent changes or development in the law.

Another traditional justification for overruling a prior case

is that a precedent may be a positive detriment to coherence

and consistency in the law, either because of inherent confu

sion created by an unworkable decision, see, e. g., Continen

tal T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania, Inc., 433 U. S. 36, 47-48

(1977); Swift & Co. v. Wickham, 382 U. S. I l l , 124-125

(1965), or because the decision poses a direct obstacle to the

realization of important objectives embodied in other laws,

see, e. g . , Rodriguez de Quijas, supra, a t ------ ; Boys Mar

kets, Inc. v. Retail Clerks, supra, at 240-241. In this re

gard, we do not find Runyon to be unworkable or confusing.

Respondent and various amici have urged that Runyon’s, in

terpretation of § 1981, as applied to contracts of employment,

frustrates the objectives of Title VII. The argument is that

a substantial overlap in coverage between the two statutes,

given the considerable differences in their remedial schemes,

undermines Congress’ detailed efforts in Title VII to resolve

disputes about racial discrimination in private employment

through conciliation rather than litigation as an initial matter.

After examining the point with care, however, we believe

6 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

that a sound construction of the language of § 1981 yields an

interpretation which does not frustrate the congressional ob

jectives in Title VII to any significant degree. See Part III,

infra.

Finally, it has sometimes been said that a precedent

becomes more vulnerable as it becomes outdated and after

being ‘“ tested by experience, has been found to be incon

sistent with the sense of justice or with the social welfare.’ ”

Runyon, 427 U. S., at 191 (Stevens, J., concurring), quot

ing B. Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process 149

(1921). Whatever the effect of this consideration may be in

statutory cases, it offers no support for overruling Runyon.

In recent decades, state and federal legislation has been

enacted to prohibit private racial discrimination in many as

pects of our society. Whether Runyon’s interpretation of

§ 1981 as prohibiting racial discrimination in the making and

enforcement of private contracts is right or wrong as an origi

nal matter, it is certain that it is not inconsistent with the

prevailing sense of justice in this country. To the contrary,

Runyon is entirely consistent with our society’s deep com

mitment to the eradication of discrimination based on a per

son’s race or the color of his or her skin. See Bob Jones Uni

versity v. United States, 461 U. S. 574, 593 (1983) (“every

pronouncement of this Court and myriad Acts of Congress

and Executive Orders attest a firm national policy to prohibit

racial segregation and discrimination”); see also Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); Plessy v. Fergu

son, 163 U. S. 537, 559 (1896) (Harlan, J., dissenting) (“The

law regards man as man, and takes no account of his . . .

color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law

of the land are involved”).1

‘ J u s t i c e B r e n n a n chides us for .ignoring what he considers “two very

obvious reasons” for adhering to Runyon. Post, at 3. First, he argues at

length that Runyon was correct as an initial matter. See post, at 3-11.

As we have said, however, see supra, at 3-4, it is unnecessary for us to

address this issue because we agree that, whether or not Runyon was cor-

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 7

We decline to overrule Runyon and acknowledge that its

holding remains the governing law in this area.

I ll

Our conclusion that we should adhere to our decision in

Runyon that § 1981 applies to private conduct is not enough

to decide this case. We must decide also whether the con

duct of which petitioner complains falls within one of the

enumerated rights protected by § 1981.

A

Section 1981 reads as follows:

“All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and Ter-

reet as an initial matter, there is no special justification for departing here

from the rule of stare decisis.

J u s t i c e B r e n n a n objects also to the fact that our stare decisis analysis

places no reliance on the fact that Congress itself has not overturned the

interpretation of § 1981 contained in Runyon, and in effect has ratified our

decision in that case. See post, at 11-17. This is no oversight on our

part. As we reaffirm today, considerations of stare decisis have added

force in statutory cases because Congress may alter what we have done by

amending the statute. In constitutional cases, by contrast, Congress lacks

this option, and an incorrect or outdated precedent may be overturned only

by our own reconsideration or by constitutional amendment. See supra,

at 4. It does not follow, however, that Congress’ failure to overturn a

statutory precedent is reason for this Court to adhere to it. It is ‘im

possible to assert with any degree of assurance that congressional failure to

act represents” affirmative congressional approval of the Court’s statutory

interpretation. Johnson v. Transportation Agency, 480 U. S. 616, 671-

672 (1987) (ScA LIA, J., dissenting). Congress may legislate, moreover,

only through the passage of a bill which is approved by both Houses and

signed by the President. See U. S. Const., Art. I, §7, cl. 2. Congres

sional inaction cannot amend a duly enacted statute. We think also that

the materials relied upon by J u s t i c e B r e n n a n as “more positive signs of

Congress’ views,” which are the failure of an amendment to a different

statute offered before our decision in Runyon, see post, at 12-15, and the

passage of an attorney’s fee statute having nothing to do with our holding

in Runyon, see post, at 15-16, demonstrate well the danger of placing

undue reliance on the concept of congressional “ratification.

8 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

ritory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties,

give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws

and proceedings for the security of persons and property

as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to

like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and

exactions of every kind, and to no other.” Rev. Stat.

§ 1977.

The most obvious feature of the provision is the restriction

of its scope to forbidding discrimination in the “mak[ing]

and enforcement]” of contracts alone. Where an alleged act

of discrimination does not involve the impairment of one of

these specific rights, § 1981 provides no relief. Section 1981

cannot be construed as a general proscription of racial dis

crimination in all aspects of contract relations, for it ex

pressly prohibits discrimination only in the making and en

forcement of contracts. See also Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer

Co., 392 U. S. 409, 436 (1968) (§ 1982, the companion statute

to § 1981, was designed “to prohibit all racial discrimination,

whether or not under color of law, with respect to the rights

enumerated therein”) (emphasis added); Georgia v. Rachel,

384 U. S. 780, 791 (1966) (“ The legislative history of the 1866

Act clearly indicates that Congress intended to protect a lim

ited category of rights”).

By its plain terms, the relevant provision in § 1981 protects

two rights: “the same right . . . to make . . . contracts”

and “the same right . . . to . . . enforce contracts.” The

first of these protections extends only to the formation of a

contract, but not to problems that may arise later from the

conditions of continuing employment. The statute prohibits,

when based on race, the refusal to enter into a contract with

someone, as well as the offer to make a contract only on dis

criminatory terms. But the right to make contracts does not

extend, as a matter of either logic or semantics, to conduct by

the employer after the contract relation has been established,

including breach of the terms of the contract or imposition of

discriminatory working conditions. Such postformation con-

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 9

duct does not involve the right to make a contract, but rather

implicates the performance of established contract obliga

tions and the conditions of continuing employment, matters

more naturally governed by state contract law and Title VII.

See infra, a t ------ .

The second of these guarantees, “the same right. . . to . . .

enforce contracts . . . as is enjoyed by white citizens,” em

braces protection of a legal process, and of a right of access

to legal process, that will address and resolve contract-law

claims without regard to race. In this respect, it prohibits

discrimination that infects the legal process in ways that pre

vent one from enforcing contract rights, by reason of his or

her race, and this is so whether this discrimination is attrib

uted to a statute or simply to existing practices. It also cov

ers wholly private efforts to impede access to the courts or

obstruct nonjudicial methods of adjudicating disputes about

the force of binding obligations, as well as discrimination by

private entities, such as labor unions, in enforcing the terms

of a contract. Following this principle and consistent with

our holding in Runyon that § 1981 applies to private conduct,

we have held that certain private entities such as labor un

ions, which bear explicit responsibilities to process griev

ances, press claims, and represent member in disputes over

the terms of binding obligations that run from the employer

to the employee, are subject to liability under § 1981 for racial

discrimination in the enforcement of labor contracts. See

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U. S. 656 (1987). The

right to enforce contracts does not, however, extend beyond

conduct by an employer which impairs an employee’s ability

to enforce through legal process his or her established con

tract rights. As J u s t ic e W h it e put it with much force in

Runyon, one cannot seriously “contend that the grant of the

other rights enumerated in §1981, [that is, other than the

right to “make” contracts,] i. e., the rights ‘to sue, be parties,

give evidence,’ and ‘enforce contracts’ accomplishes anything

other than the removal of legal disabilities to sue, be a party,

10 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

testify or enforce a contract. Indeed, it is impossible to give

such language any other meaning.” 427 U. S., at 195, n. 5

(dissenting opinion) (emphasis in original).

B

Applying these principles to the case before us, we agree

with the Court of Appeals that petitioner’s racial harassment

claim is not actionable under § 1981. Petitioner has alleged

that during her employment with respondent, she was sub

jected to various forms of racial harassment from her super

visor. As summarized by the Court of Appeals, petitioner

testified that

“ [her supervisor] periodically stared at her for several

minutes at a time; that he gave her too many tasks, caus

ing her to complain that she was under too much pres

sure; that among the tasks given her were sweeping and

dusting, jobs not given to white employees. On one oc

casion, she testified, [her supervisor] told [her] that

blacks are known to work slower than whites. Accord

ing to [petitioner, her supervisor] also criticized her in

staff meetings while not similarly criticizing white em

ployees.” 805 F. 2d, at 1145.

Petitioner also alleges that she was passed over for promo

tion, not offered training for higher level jobs, and denied

wage increases, all because of her race.2

With the exception perhaps of her claim that respondent

refused to promote her to a position as an accountant, see

Part IV, infra, none of the conduct which petitioner alleges

as part of the racial harassment against her involves either a

refusal to make a contract with her or the impairment of her

ability to enforce her established contract rights. Rather,

2 In addition, another of respondent’s managers testified that when he

recommended a different black person for a position as a data processor,

petitioner’s supervisor stated that he did not “need any more problems

around here,” and that he would “search for additional people who are not

black.” Tr. 2-160 to 2-161.

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 11

the conduct which petitioner labels as actionable racial ha

rassment is postformation conduct by the employer relating

to the terms and conditions of continuing employment. This

is apparent from petitioner’s own proposed jury instruction

on her § 1981 racial harassment claim:

. . The plaintiff has also brought an action for

harassment in employment against the defendant, under

the same statute, 42 USC § 1981. An employer is guilty

of racial discrimination in employment where it has

either created or condoned a substantially discrimina

tory work environment. An employee has a right to

work in an environment free from racial prejudice. If

the plaintiff has proven by a preponderance of the evi

dence that she was subjected to racial harassment by her

manager while employed at the defendant, or that she

was subjected to a work environment not free from ra

cial prejudice which was either created or condoned by

the defendant, then it would be your duty to find for

plaintiff on this issue.” 1 Record, Doc. No. 18, p. 4

(emphasis added).

Without passing on the contents of this instruction, it is plain

to us that what petitioner is attacking are the conditions of

her employment.

This type of conduct, reprehensible though it be if true, is

not actionable under § 1981, which covers only conduct at the

initial formation of the contract and conduct which impairs

the right to enforce contract obligations through legal proc

ess. Rather, such conduct is actionable under the more ex

pansive reach of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The latter statute makes it unlawful for an employer to “dis

criminate against any individual with respect to his com

pensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment.”

42 U. S. C. § 2000e-2(a)(l). Racial harassment in the course

of employment is actionable under Title VII’s prohibition

against discrimination in the “terms, conditions, or privileges

of employment.” “ [T]he [Equal Employment Opportunity

12 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

Commission (EEOC)] has long recognized that harassment

on the basis of race . . . is an unlawful employment practice

in violation of §703 of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act.”

See EEOC Compliance Manual §615.7 (1982). While this

Court has not yet had the opportunity to pass directly upon

this interpretation of Title VII, the lower federal courts have

uniformly upheld this view,8 and we implicitly have approved

it in a recent decision concerning sexual harassment, Meritor

Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477 U. S. 57, 65-66 (1986). As we

said in that case, “harassment [which is] sufficiently severe

or pervasive ‘to alter the conditions of [the victim’s] employ

ment and create an abusive working environment,” ’ id., at

67, is actionable under Title VII because it “affects a ‘term,

condition, or privilege’ of employment,” ibid.

Interpreting § 1981 to cover postformation conduct unre

lated to an employee’s right to enforce her contract, such as

incidents relating to the conditions of employment, is not only

inconsistent with that statute’s limitation to the making and

enforcement of contracts, but would also undermine the de

tailed and well-crafted procedures for conciliation and reso

lution of Title VII claims. In Title VII, Congress set up

an elaborate administrative procedure, implemented through

the EEOC, that is designed to assist in the investigation

of claims of racial discrimination in the workplace and to

work towards the resolution of these claims through concilia

tion rather than litigation. See 42 U. S. C. §2000e-5(b).

Only after these procedures have been exhausted, and the

plaintiff has obtained a “right to sue” letter from the EEOC,

may she bring a Title VII action in court. See 42 U. S. C.

§2000e-5(f)(l). Section 1981, by contrast, provides no

administrative review or opportunity for conciliation. 3

3 See, e. g., Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v. St. Louis, 549

F. 2d 506, 514-515 (CA8), cert, denied sub nom. Banta v. United States,

434 U. S. 819 (1977); Rogers v. EEOC, 454 F. 2d 234 (CA5 1971), cert,

denied, 406 U. S. 957 (1972).

Where conduct is covered by both § 1981 and Title VII, the

detailed procedures of Title VII are rendered a dead letter,

as the plaintiff is free to pursue a claim by bringing suit under

§ 1981 without resort to those statutory prerequisites. We

agree that, after Runyon, there is some necessary overlap

between Title VII and § 1981, and that where the statutes do

in fact overlap we are not at liberty “to infer any positive

preference for one over the other.” Johnson v. Railway Ex

press Agency, Inc., 421 U. S., at 461. We should be reluc

tant, however, to read an earlier statute broadly where the

result is to circumvent the detailed remedial scheme con

structed in a later statute. See United States v. Fausto, 484

U. S. 439 (1988). That egregious racial harassment of em

ployees is forbidden by a clearly applicable law (Title VII),

moreover, should lessen the temptation for this Court to

twist the interpretation of another statute (§ 1981) to cover

the same conduct. In the particular case before us, we do

not know for certain why petitioner chose to pursue only

remedies under § 1981, and not under Title VII. See 805 F.

2d, at 1144, n.; Tr. of Oral Arg. 15-16, 23 (Feb. 29, 1988).

But in any event, the availability of the latter statute should

deter us from a tortuous construction of the former statute to

cover this type of claim.

By reading § 1981 not as a general proscription of racial dis

crimination in all aspects of contract relations, but as limited

to the enumerated rights within its express protection, spe

cifically the right to make and enforce contracts, we may pre

serve the integrity of Title VII’s procedures without sacrific

ing any significant coverage of the civil rights laws.4 Of

4 Unnecessary overlap between Title VII and § 1981 would also serve to

upset the delicate balance between employee and employer rights struck

by Title VII in other respects. For instance, a plaintiff in a Title VII ac

tion is limited to a recovery of backpay, whereas under § 1981 a plaintiff

may be entitled to plenary compensatory damages, as well as punitive

damages in an appropriate case. Both the employee and employer will be

unlikely to agree to a conciliatory resolution of the dispute under Title VII

if the employer can be found liable for much greater amounts under § 1981.

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 13

14 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

course, some overlap will remain between the two statutes:

specifically, a refusal to enter into an employment contract on

the basis of race. Such a claim would be actionable under

Title VII as a “refus[al] to hire” based on race, 42 U. S. C.

§ 2000e-2(a), and under § 1981 as an impairment of “the same

right . . . to make . . . contracts . . . as . . . white citizens,”

42 U. S. C. §1981. But this is precisely where it would

make sense for Congress to provide for the overlap. At this

stage of the employee-employer relation Title V II’s media

tion and conciliation procedures would be of minimal effect,

for there is not yet a relation to salvage.

C

The Solicitor General and J u s t ic e B r e n n a n offer two al

ternative interpretations of § 1981. The Solicitor General ar

gues that the language of § 1981, especially the words “the

same right,” requires us to look outside § 1981 to the terms of

particular contracts and to state law for the obligations and

covenants to be protected by the federal statute. Under this

view, § 1981 has no actual substantive content, but instead

mirrors only the specific protections that are afforded under

the law of contracts of each State. Under this view, racial

harassment in the conditions of employment is actionable

when, and only when, it amounts to a breach of contract

under state law. We disagree. For one thing, to the extent

that it assumes that prohibitions contained in § 1981 incorpo

rate only those protections afforded by the States, this the

ory is directly inconsistent with Runyon, which we today de

cline to overrule. A more fundamental failing in the

Solicitor’s argument is that racial harassment amounting to

breach of contract, like racial harassment alone, impairs nei

ther the right to make nor the right to enforce a contract. It

is plain that the former right is not implicated directly by an

employer’s breach in the performance of obligations under a

contract already formed. Nor is it correct to say that racial

harassment amounting to a breach of contract impairs an em

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 15

ployee’s right to enforce his contract. To the contrary, con

duct amounting to a breach of contract under state law is pre

cisely what the language of § 1981 does not cover. That is

because, in such a case, provided that plaintiff’s access to

state court or any other dispute resolution process has not

been impaired by either the State or a private actor, see

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U. S. 656 (1987), the

plaintiff is free to enforce the terms of the contract in state

court, and cannot possibly assert, by reason of the breach

alone, that he has been deprived of the same right to enforce

contracts as is enjoyed by white citizens.

In addition, interpreting §1981 to cover racial harass

ment amounting to a breach of contract would federalize all

state-law claims for breach of contract where racial animus

is alleged, since § 1981 covers all types of contracts, not just

employment contracts. Although we must do so when Con

gress plainly directs, as a rule we should be and are “re

luctant to federalize” matters traditionally covered by state

common law. Santa Fe Industries, Inc. v. Green, 430 U. S.

462, 479 (1977); see also Sedima S. P. R. L. v. Imrex Co.,

473 U. S. 479, 507 (1985) (M a r s h a l l , J., dissenting). By

confining § 1981 to the impairment of the specific rights to

make and enforce contracts, Congress cannot be said to have

intended such a result with respect to breach of contract

claims. It would be no small paradox, moreover, that under

the interpretation of § 1981 offered by the Solicitor General,

the more a State extends its own contract law to protect em

ployees in general and minorities in particular, the greater

would be the potential displacement of state law by § 1981.

We do not think § 1981 need be read to produce such a pecu

liar result.

J u s t ic e B r e n n a n , for his part, would hold that racial ha

rassment is actionable under § 1981 when “the acts constitut

ing harassment [are] sufficiently severe or pervasive as effec

tively to belie any claim that the contract was entered into in

a racially neutral manner.” See post, at 19. We do not find

16 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

this standard an accurate or useful articulation of which con

tract claims are actionable under § 1981 and which are not.

The fact that racial harassment is “severe or pervasive” does

not by magic transform a challenge to the conditions of em

ployment, not actionable under § 1981, into a viable challenge

to the employer’s refusal to make a contract. We agree that

racial harassment may be used as evidence that a divergence

in the explicit terms of particular contracts is explained by

racial animus.5 Thus, for example, if a potential employee is

offered (and accepts) a contract to do a job for less money

than others doing like work, evidence of racial harassment in

the workplace may show that the employer, at the time of

formation, was unwilling to enter into a nondiscriminatory

contract. However, and this is the critical point, the ques

tion under § 1981 remains whether the employer, at the time

of the formation of the contract, in fact intentionally refused

to enter into a contract with the employee on racially neutral

terms. The plaintiff’s ability to plead that the racial harass

ment is “severe or pervasive” should not allow him to boot

strap a challenge to the conditions of employment (actionable,

if at all, under Title VII) into a claim under § 1981 that the

employer refused to offer the petitioner the “same right to

. . . make” a contract. We think it clear that the conduct

challenged by petitioner relates not to her employer’s refusal

to enter into a contract with her, but rather to the conditions

of her employment.6

5 This was the permissible use of evidence of racial harassment that the

Fourth Circuit, in its decision below, envisioned for § 1981 cases. See 805

F. 2d 1143, 1145 (1986).

6 In his separate opinion, J u s t i c e S t e v e n s construes the phrase “the

same right . . . to make . . . contracts” with ingenuity to cover various

postformation conduct by the employer. But our task here is not to con

strue § 1981 to punish all acts of discrimination in contracting in a like fash

ion, but rather merely to give a fair reading to scope of the statutory terms

used by Congress. We adhere today to our decision in Runyon that § 1981

reaches private conduct, but do not believe that holding compels us to read

the statutory terms “make” and “enforce” beyond their plain and common

IV

Petitioner’s claim that respondent violated § 1981 by failing

to promote her, because of race, to a position as an intermedi

ate accounting clerk is a different matter. As a preliminary

point, we note that the Court of Appeals distinguished be

tween petitioner’s claims of racial harassment and discrimina

tory promotion, stating that although the former did not give

rise to a discrete § 1981 claim, “ [cjlaims of racially discrimi

natory . . . promotion go to the very existence and nature of

the employment contract and thus fall easily within § 1981’s

protection.” 805 F. 2d, at 1145. We think that somewhat

overstates the case. Consistent with what we have said in

Part III, supra, the question whether a promotion claim is

actionable under § 1981 depends upon whether the nature of

the change in position was such that it involved the opportu

nity to enter into a new contract with the employer. If so,

then the employer’s refusal to enter the new contract is

actionable under § 1981. In making this determination, a

lower court should give a fair and natural reading to the stat

utory phrase “the same right . . . to make . . . contracts,”

and should not strain in an undue manner the language of

§ 1981. Only where the promotion rises to the level of an

opportunity for a new and distinct relation between the em

ployee and the employer is such a claim actionable under

§ 1981. Cf. Hishon v. King & Spaulding, 467 U. S. 69 (1984)

(refusal of law firm to accept associate into partnership)

(Title VII). Because respondent has not argued at any stage

that petitioner’s promotion claim is not cognizable under

§ 1981, we need not address the issue further here.

This brings us to the question of the District Court’s jury

instructions on petitioner’s promotion claim. We think the

District Court erred when it instructed the jury that peti

tioner had to prove that she was better qualified than the

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 17

sense meaning. We believe that the lower courts will have little difficulty

applying the straightforward principles that we announce today.

18 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

white employee who allegedly received the promotion. In

order to prevail under § 1981, a plaintiff must prove purpose

ful discrimination. General Building Contractors Assn.,

Inc. v. Pennsylvania, 458 U. S. 375, 391 (1982). We have

developed, in analogous areas of civil rights law, a care

fully designed framework of proof to determine, in the con

text of disparate treatment, the ultimate issue of whether

the defendant intentionally discriminated against the plain

tiff. See Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U. S. 248 (1981); McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

U. S. 792 (1973). We agree with the Court of Appeals that

this scheme of proof, structured as a “sensible, orderly way

to evaluate the evidence in light of common experience as it

bears on the critical question of discrimination,” Fumco Con

struction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U. S. 567, 577 (1978), should

apply to claims of racial discrimination under § 1981.

Although the Court of Appeals recognized that the McDon

nell Douglas/Burdine scheme of proof should apply in § 1981

cases such as this one, it erred in describing petitioner’s bur

den. Under our well-established framework, the plaintiff

has the initial burden of proving, by the preponderance of the

evidence, a prima facie case of discrimination. Burdine, 450

U. S., at 252-253. The burden is not onerous. Id., at 253.

Here, petitioner need only prove by a preponderance of the

evidence that she applied for and was qualified for an avail

able position, that she was rejected, and that after she was

rejected respondent either continued to seek applicants for

the position, or, as is alleged here, filled the position with a

white employee. See id., at 253, and n. 6; McDonnell Doug

las, supra, at 802.7

7 Here, respondent argues that petitioner cannot make out a prima facie

case on her promotion claim because she did not prove either that respond

ent was seeking applicants for the intermediate accounting clerk position

or that the white employee named to fill that position in fact received a

“promotion” from her prior job. Although we express no opinion on the

merits of these claims, we do emphasize that in order to prove that she was

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 19

Once the plaintiff establishes a prima facie case, an in

ference of discrimination arises. See Burdine, 450 U. S.,

at 254. In order to rebut this inference, the employer must

present evidence that the plaintiff was rejected, or the other

applicant was chosen, for a legitimate nondiscriminatory

reason. See ibid. Here, respondent presented evidence

that it gave the job to the white applicant because she was

better qualified for the position, and therefore rebutted

any presumption of discrimination that petitioner may have

established. At this point, as our prior cases make clear,

petitioner retains the final burden of persuading the jury

of intentional discrimination. See id., at 256.

Although petitioner retains the ultimate burden of persua

sion, our cases make clear that she must also have the oppor

tunity to demonstrate that respondent’s proffered reasons for

its decision were not its true reasons. Ibid. In doing so,

petitioner is not limited to presenting evidence of a certain

type. This is where the District Court erred. The evidence

which petitioner can present in an attempt to establish that

respondent’s stated reasons are pretextual may take a vari

ety of forms. See McDonnell Douglas, supra, at 804-805;

Fumco Construction Corp., supra, at 578; cf. United States

Postal Service Bd. of Governors v. Athens, 460 U. S. 711,

714, n. 3 (1983). Indeed, she might seek to demonstrate

that respondent’s claim to have promoted a better-qualified

applicant was pretextual by showing that she was in fact

better qualified than the person chosen for the position. The

District Court erred, however, in instructing the jury that

in order to succeed petitioner was required to make such

a showing. There are certainly other ways in which peti

tioner could seek to prove that respondent’s reasons were

pretextual. Thus, for example, petitioner could seek to

persuade the jury that respondent had not offered the true

denied the same right to make and enforce contracts as white citizens, peti

tioner must show, inter alia, that she was in fact denied an available

position.

20 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

reason for its promotion decision by presenting evidence

of respondent’s past treatment of petitioner, including the

instances of the racial harassment which she alleges and

respondent’s failure to train her for an accounting position.

See supra, a t ------ . While we do not intend to say this evi

dence necessarily would be sufficient to carry the day, it can

not be denied that it is one of the various ways in which peti

tioner might seek to prove intentional discrimination on the

part of respondent. She may not be forced to pursue any

particular means of demonstrating that respondent’s stated

reasons are pretextual. It was, therefore, error for the Dis

trict Court to instruct the jury that petitioner could carry her

burden of persuasion only by showing that she was in fact

better qualified than the white applicant who got the job.

V

The law now reflects society’s consensus that discrimina

tion based on the color of one’s skin is a profound wrong

of tragic dimension. Neither our words nor our decisions

should be interpreted as signaling one inch of retreat from

Congress’ policy to forbid discrimination in the private, as

well as the public, sphere. Nevertheless, in the area of pri

vate discrimination, to which the ordinance of the Constitu

tion does not directly extend, our role is limited to interpret

ing what Congress may do and has done. The statute before

us, which is only one part of Congress’ extensive civil rights

legislation, does not cover the acts of harassment alleged

here.

In sum, we affirm the Court of Appeals’ dismissal of peti

tioner’s racial harassment claim as not actionable under

§ 1981. The Court of Appeals erred, however, in holding

that petitioner could succeed in her discriminatory promotion

claim under § 1981 only by proving that she was better quali

fied for the position of intermediate accounting clerk than

the white employee who in fact was promoted. The judg

ment of the Court of Appeals is therefore vacated insofar as it

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 21

relates to petitioner’s discriminatory promotion claim, and

the case is remanded for further proceedings consistent with

this opinion.

It is so ordered.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 87-107

BRENDA PATTERSON, PETITIONER v.

McLEAN CREDIT UNION

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

[June 15, 1989]

J u s t ic e B r e n n a n , with whom J u s t ic e M a r s h a l l and

J u s t ic e B l a c k m u n join, and with whom J u s t ic e St e v e n s

joins as to Parts II-B, II-C, and III, concurring in the judg

ment in part and dissenting in part.

What the Court declines to snatch away with one hand, it

takes with the other. Though the Court today reaffirms

§1981’s applicability to private conduct, it simultaneously

gives this landmark civil rights statute a needlessly cramped

interpretation. The Court has to strain hard to justify this

choice to confine § 1981 within the narrowest possible scope,

selecting the most pinched reading of the phrase “same right

to make a contract,” ignoring powerful historical evidence

about the Reconstruction Congress’ concerns, and bolstering

its parsimonious rendering by reference to a statute enacted

nearly a century after § 1981, and plainly not intended to af

fect its reach. When it comes to deciding whether a civil

rights statute should be construed to further our Nation’s

commitment to the eradication of racial discrimination, the

Court adopts a formalistic method of interpretation anti

thetical to Congress’ vision of a society in which contractual

opportunities are equal. I dissent from the Court’s holding

that § 1981 does not encompass Patterson’s racial harassment

claim.

2 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

I

Thirteen years ago, in deciding Runyon v. McCrary, this

Court treated as already “well established” the proposition

that “ § 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27, 42

U. S. C. § 1981, prohibits racial discrimination in the making

and enforcement of private contracts,” as well as state-man

dated inequalities, drawn along racial lines, in individuals’

ability to make and enforce contracts. 427 U. S. 160, 168

(1976), citing Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421

U. S. 454 (1975); Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation

Assn., Inc., 410 U. S. 431 (1973); and Jones v. Alfred H.

Mayer Co., 392 U. S. 409 (1968). Since deciding Runyon,

we have upon a number of occasions treated as settled law its

interpretation of § 1981 as extending to private discrimina

tion. Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U. S. 656 (1987);

Saint Francis College v. Al-Khazraji, 481 U. S. 604 (1987);

General Building Contractors Assn., Inc. v. Pennsylvania,

458 U. S. 375 (1982); Delaware State College v. Ricks, 449

U. S. 250 (1980); McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co.,

427 U. S. 273 (1976). We have also reiterated our holding in

Jones that § 1982 similarly applies to private discrimination in

the sale or rental of real or personal property—a holding ar

rived at through an analysis of legislative history common to

both § 1981 and § 1982. Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb,

481 U. S. 615 (1987); Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc.,

396 U. S. 229 (1969).

The Court’s reaffirmation of this long and consistent line

of precedents establishing that § 1981 encompasses private

discrimination is based upon its belated decision to adhere

to the principle of stare decisis—a decision that could readily

and would better have been made before the Court decided to

put Runyon and its progeny into question by ordering re

argument in this case. While there is an exception to stare

decisis for precedents that have proved “outdated, . . . un

workable, or otherwise legitimately vulnerable to serious

reconsideration,” Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U. S. 254, 266

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 3

(1986), it has never been arguable that Runyon falls within

it. Rather, Runyon is entirely consonant with our society’s

deep commitment to the eradication of discrimination based

on a person’s race or the color of her skin. See Bob Jones

University v. United States, 461 U. S. 574, 593 (1983)

(“every pronouncement of this Court and myriad Acts of

Congress and Executive Orders attest a firm national policy

to prohibit racial segregation and discrimination”). That

commitment is not bounded by legal concepts such as “state

action,” but is the product of a national consensus that racial

discrimination is incompatible with our best conception of our

communal life, and with each individual’s rightful expectation

that her full participation in the community will not be contin

gent upon her race. In the past, this Court has overruled

decisions antagonistic to our Nation’s commitment to the

ideal of a society in which a person’s opportunities do not de

pend on her race, e. g., Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483 (1954) (overruling Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S.

537 (1896)), and I find it disturbing that the Court has in this

case chosen to reconsider, without any request from the par

ties, a statutory construction so in harmony with that ideal.

Having decided, however, to reconsider Runyon, and now

to reaffirm it by appeal to stare decisis, the Court glosses

over what are in my view two very obvious reasons for refus

ing to overrule this interpretation of § 1981: that Runyon was

correctly decided, and that in any event Congress has ratified

our construction of the statute.

A

A survey of our cases demonstrates that the Court’s inter

pretation of § 1981 has been based upon a full and considered

review of the statute’s language and legislative history, as

sisted by careful briefing, upon which no doubt has been cast

by any new information or arguments advanced in the briefs

filed in this case.

4 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

In Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U. S. 409 (1968), this

Court considered whether § 1982, which provides that “ [a]ll

citizens of the United States shall have the same right, in

every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citizens

thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey

real and personal property,” prohibits private discrimination

on the basis of race, and if so, whether the statute is con

stitutional. The Court held, over two dissenting votes, that

§ 1982 bars private as well as public racial discrimination,

and that the statute was a valid exercise of Congress’ power

under §2 of the Thirteenth Amendment to identify the

badges and incidents of slavery and to legislate to end them.

The Court began its careful analysis in Jones by noting the

expansive language of § 1982, and observing that a black citi

zen denied the opportunity to purchase property as a result

of discrimination by a private seller cannot be said to have

the “same right” to purchase property as a white citizen.

392 U. S., at 420-421. The Court also noted that, in its orig

inal form, § 1982 had been part of § 1 of the Civil Rights Act

of 1866,1 and that §2 of the 1866 Act provided for criminal

penalties against any person who violated rights secured or

‘ Act of Apr. 9, 1866, ch. 31, § 1, 14 Stat. 27. Section 1 provided:

“[C]itizens, of every race and color, without regard to any previous con

dition of slavery or involuntary servitude, . . . shall have the same right, in

every State and Territory in the United States, to make and enforce con

tracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease,

sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal ben

efit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as

is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

and penalties, and to none other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation,

or custom, to the contrary notwithstanding.”

All members of the Court agreed in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392

U. S. 409 (1968), that intervening revisions in the property clause of § 1—

the reenactment of the 1866 Act in § 18 of the Voting Rights Act of 1870,

ch. 114, § 18, 16 Stat. 144, the codification of the property clause in § 1978

of the Revised Statutes of 1874, and its recodification as 42 U. S. C.

§ 1982—had not altered its substance. Jones, 392 U. S., at 436-437 (opin

ion of the Court); id., at 453 (dissenting opinion).

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 5

protected by the Act “under color of any law, statute, ordi

nance, regulation, or custom.” 392 U. S., at 424-426. This

explicit limitation upon the scope of § 2, to exclude criminal

liability for private violations of § 1, strongly suggested that

§ 1 itself prohibited private discrimination, for otherwise the

limiting language of §2 would have been redundant. Ibid.

Although Justice Harlan, in dissent, thought a better ex

planation of the language of §2 was that it “was carefully

drafted to enforce all of the rights secured by § 1,” id., at 454,

it is by no means obvious why the dissent’s view should be

regarded as the more accurate interpretation of the structure

of the 1866 Act.2 * * * * * 8

The Court then engaged in a particularly thorough analysis

of the legislative history of §1 of the 1866 Act, id., at

422-437, which had been discussed at length in the briefs

of both parties and their amici.s While never doubting

that the prime targets of the 1866 Act were the Black Codes,

in which the Confederate States imposed severe disabilities

on the freedmen in an effort to replicate the effects of slav

ery, see, e. g., 1 C. Fairman, Reconstruction and Reunion

1864-1888, pp. 110-117 (1971) (discussing Mississippi’s Black

Codes), the Court concluded that Congress also had intended

§ 1 to reach private discriminatory conduct. The Court cited

2 In support of its view, the Court in Jones quoted from an exchange

during the House debate on the civil rights bill. When Congressman Loan

of Missouri asked the Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee why § 2

had been limited to those who acted under color of law, he was told, not

that the statute had no application at all to those who had not acted under

color of law, but that the limitation had been imposed because it was not

desired to make ‘“ a general criminal code for the States.’ ” Id., at 425,

n. 33, quoting Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 1120 (1866). Justice

Harlan in dissent conceded that the Court’s interpretation of this exchange

as supporting a broader reading of § 1 was “a conceivable one.” 392 U. S.,

at 470.

8 See, e. g., Brief for Petitioners 12-16, Brief for Respondents 7-24,

Brief for United States as Amicus Curiae 28-35, 38-51, and Brief for Na

tional Committee Against Discrimination in Housing et al. as Amici Curiae

9-39, in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 0. T. 1967, No. 45.

6 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

a bill (S. 60) to amend the Freedmen’s Bureau Act, intro

duced prior to the civil rights bill, and passed by both Houses

during the 39th Congress (though it was eventually vetoed

by President Johnson), as persuasive evidence that Congress

was fully aware that any newly recognized rights of blacks

would be as vulnerable to private as to state infringement.

392 U. S., at 423, and n. 30. The amendment would have

extended the jurisdiction of the Freedmen’s Bureau over all

cases in the former Confederate States involving the denial

on account of race of rights to make and enforce contracts or

to purchase or lease property, “in consequence of any State

or local law, ordinance, police, or other regulation, custom, or

'prejudice.” Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 209 (1866)

(emphasis added). When the civil rights bill was subse

quently introduced, Representative Bingham specifically

linked it in scope to S. 60. Id., at 1292. See Jones, supra,

at 424, n. 31.

The Court further noted that there had been “an imposing

body of evidence [before Congress] pointing to the mistreat

ment of Negroes by private individuals and unofficial groups,

mistreatment unrelated to any hostile state legislation.” 392

U. S., at 427. This evidence included the comprehensive re

port of Major General Carl Schurz on conditions in the Con

federate States. This report stressed that laws were only

part of the problem facing the freedmen, who also encoun

tered private discrimination and often brutality.4 The con-

J Report of C. Schurz, S. Exec. Doc. No. 2, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1865). The Schurz report is replete with descriptions of private dis

crimination, relating both to the freedmen’s ability to enter into contracts,

and to their treatment once under contract. It notes, for example, that

some planters had initially endeavored to maintain “the relation of master

and slave, partly by concealing from [their slaves] the great changes that

had taken place, and partly by terrorizing them into submission to their

behests.” Id., at 15. It portrays as commonplace the use of “force and

intimidation” to keep former slaves on the plantations:

“In many instances negroes who walked away from the plantations, or

were found upon the roads, were shot or otherwise severely punished,

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 7

gressional debates on the Freedmen’s Bureau and civil rights

bills show that legislators were well aware that the rights of

former slaves were as much endangered by private action as

by legislation. See id., at 427-428, and nn. 37-40. To be

sure, there is much emphasis in the debates on the evils of

the Black Codes. But there are also passages that indicate

that Congress intended to reach private discrimination that

posed an equal threat to the rights of the freedmen. See id.,

at 429-437. Senator Trumbull, for example, promised to in

troduce a bill aimed not only at “local legislation,” but at any

“prevailing public sentiment” that blacks in the South “should

continue to be oppressed and in fact deprived of their free-

which was calculated to produce the impression among those remaining

with their masters that an attempt to escape from slavery would result in

certain destruction.” Id., at 17.

In Georgia, Schurz reported, “the reckless and restless characters of that

region had combined to keep the negroes where they belonged,” shooting

those caught trying to escape. Id., at 18. The effect of this private

violence against those who tried to leave their former masters was that

“large numbers [of freedmen], terrified by what they saw and heard, qui

etly remained under the restraint imposed upon them.” Ibid. See Jones,

392 U. S., at 428-429.

It must therefore have been evident to members of the 39th Congress

that, quite apart from the Black Codes, the freedmen would not enjoy the

same right as whites to contract or to own or lease property so long as pri

vate discrimination remained rampant. This broad view of the obstacles

to the freedmen’s enjoyment of contract and property rights was similarly

expressed in the Howard Report on the operation of the Freedmen’s Bu

reau, H. R. Exec. Doc. No. 11, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1865). It likewise

appears in the hearings conducted by the Joint Committee on Reconstruc

tion contemporaneously with Congress’ consideration of the civil rights bill.

See Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, 39th Cong., 1st

Sess., pts. I-IV (1866). These investigations uncovered numerous inci

dents of violence aimed at restraining southern blacks’ efforts to exercise

their new-won freedom, e. g., id., pt. Ill, p. 143, and whippings aimed

simply at making them work harder, or handed out as punishment for a

laborer’s transgressions, e. g., id., pt. IV, p. 83, as well, for example, as

refusals to pay freedmen more than a fraction of white laborers’ wages,

e. g., id., pt. II, pp. 12-13, 54-55, 234.

8 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

dom.” Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 77 (1866), quoted

in Jones, 392 U. S., at 431.5 In the Jones Court’s view,

which I share, Congress said enough about the injustice of

private discrimination, and the need to end it, to show that it

did indeed intend the Civil Rights Act to sweep that far.

Because the language of both § 1981 and § 1982 appeared

traceable to § 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the decision

in Jones was naturally taken to indicate that § 1981 also

prohibited private racial discrimination in the making and

enforcement of contracts. Thus, in Tillman v. Wheaton-

Haven Recreational Assn., Inc., 410 U. S., at 440, the Court

held that “ [i]n light of the historical interrelationship be

tween § 1981 and § 1982,” there was no reason to construe

those sections differently as they related to a claim that a

community swimming club denied property-linked member

ship preferences to blacks; and in Johnson v. Railway Ex

press Agency, Inc., 421 U. S., at 459-460, the Court stated

that “ § 1981 affords a federal remedy against discrimination

in private employment on the basis of race.” The Court only

addressed the scope of § 1981 in any depth, however, in Run

yon v. McCrary, 427 U. S. 160 (1976), where we held that

§ 1981 prohibited racial discrimination in the admissions pol

icy of a private school. That issue was directly presented

and fully briefed in Runyon.6

5 Senator Trumbull was speaking here of his Freedmen’s Bureau bill,

which was regarded as having the same scope as his later civil rights bill.

See supra, a t ------ .

For other statements indicating that § 1 reached private conduct, see

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 1118 (1866) (“Laws barbaric and treat

ment inhuman are the rewards meted out by our white enemies to our col

ored friends. We should put a stop to this at once and forever”) (Rep.

Wilson); id., at 1152 (bill aimed at “the tyrannical acts, the tyrannical

restrictions,and the tyrannical laws which belong to the condition of slav

ery”) (emphasis added) (Rep. Thayer).

'See, e. g ., Brief for Petitioners 2, 6-11, Brief for Respondents 13-22,

and Brief for United States as Amicus Curiae 13-18, in Runyon v. Me-

PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION 9

Although the Court in Runyon treated it as settled by

Jones, Tillman, and Johnson that § 1981 prohibited private

racial discrimination in contracting, it nevertheless discussed

in detail the claim that § 1981 is narrower in scope than

§ 1982. The primary focus of disagreement between the ma

jority in Runyon and J u s t ic e W h i t e ’s dissent, a debate

renewed by the parties here on reargument, concerns the ori

gins of § 1981. Section 1 of the 1866 Act was expressly reen

acted by § 18 of the Voting Rights Act of 1870. Act of May

31, 1870, ch. 114, §18, 16 Stat. 144. Section 16 of the 1870

Act nevertheless also provided “ [t]hat all persons within the

jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right in

every State and Territory in the United States to make and

enforce contracts . . . .” Ibid. Section 1 of the 1866 Act,

as reenacted by § 18 of the 1870 Act, was passed under Con

gress’ Thirteenth Amendment power to identify and legislate

against the badges and incidents of slavery, and, we held

in Jones, applied to private acts of discrimination. The dis

sent in Runyon, however, argued that § 16 of the 1870 Act

was enacted solely under Congress’ Fourteenth Amendment

power to prohibit States from denying any person the equal

protection of the laws, and could have had no application

to purely private discrimination. See Runyon, supra, at

195-201 (W h i t e , J ., dissenting). But see District of Colum

bia v. Carter, 409 U. S. 418, 424, n. 8 (1973) (suggesting

Congress has the power to proscribe purely private conduct

under § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment). When all existing

federal statutes were codified in the Revised Statutes of

1874, the Statutes included but a single provision prohibiting

racial discrimination in the making and enforcement of con

tracts — § 1977, which was identical to the current §1981.

The Runyon dissenters believed that this provision derived

solely from § 16 of the 1870 Act, that the analysis of § 1 in

Crary, O. T. 1975, No.75-62; Brief for Petitioner 17-59, in Fairfax-

Brewster School, Inc. v. Gonzales, O. T. 1975, No. 75-66.

10 PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION

Jones was of no application to § 1981, and that § 1981 hence

could not be interpreted to prohibit private discrimination.