Roper v Simmons Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 1, 2004

30 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Roper v Simmons Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Respondent, 2004. 386cf242-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8a0ac9a8-8190-4789-89f8-c623056a5121/roper-v-simmons-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

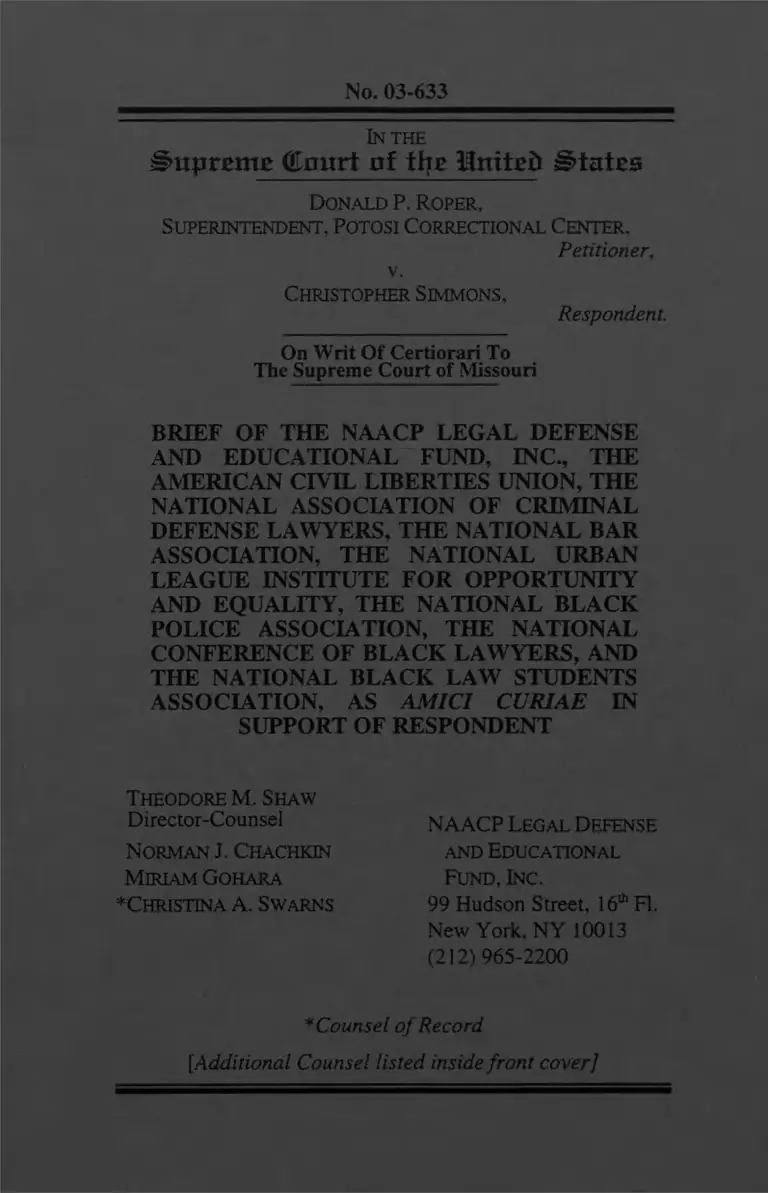

No. 03-633

In THE

Supreme (Eonrt of tfre ilnttgft sta tes

Donald P. Roper,

Superintendent, Potosi Correctional Center,

Petitioner,

v.

Christopher Simmons,

Respondent.

On Writ Of Certiorari To

The Supreme Court of Missouri

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, THE

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF CRIMINAL

DEFENSE LAWYERS, THE NATIONAL BAR

ASSOCIATION, THE NATIONAL URBAN

LEAGUE INSTITUTE FOR OPPORTUNITY

AND EQUALITY, THE NATIONAL BLACK

POLICE ASSOCIATION, THE NATIONAL

CONFERENCE OF BLACK LAWYERS, AND

THE NATIONAL BLACK LAW STUDENTS

ASSOCIATION, AS AMICI CURIAE IN

SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Miriam Gohara

♦Christina A. Swarns

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI.

New York, NY 10013

(212)965-2200

* Counsel o f Record

[Additional Counsel listed inside front cover]

[Listing of Counsel continued from cover]

Steven R. Shapiro

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

125 Broad Street

New York, NY 10025

(212) 549-2500

Dlann Y. Rust-Tierney

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

915 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, DC 20005

(202)675-2321

Charles J. Hamilton, Jr.

Paul, Hastings, Janofsky

& Walker LLP

75 East 55th Street

New York, NY 10022

(212)318-6000

Gilda Sherrod-Ali

National Conference of

Black Lawyers

116 West 111™Street

New York, NY 10027

(866) 266-5091

Barry C. Scheck

President Elect

National Association of

Criminal Defense

Lawyers

Cochran, Neufeld &

Scheck

99 Hudson Street, 8th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-9380

Clyde E. Bailey, Sr .

President

National Bar

Association

1225 11th Street, N.W.

Washington, DC 20001

(202) 842-3900

Counsel for Amici Curiae

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table o f A u th o ritie s .................................................................... ii

Interest o f Amici Curiae ..............................................................1

Sum m ary o f Argum ent ............................................................. 4

ARGUMENT —

Introduction ............ 5

Race in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice

Systems .................................................................... 6

Race Influences Capital Sentencing

Decisions in Cases Involving Juveniles............... 9

The Only Way to Insure that Race Does

Not Determine Whether a Juvenile

Defendant Will Receive a Death Sentence

Is to Hold that the Death Penalty May No

Longer Be Imposed Upon Juveniles..................15

Conclusion.............................................................. 19

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases:

Alexander v. Louisiana,

405 U.S. 625 (1 9 7 2 ) ........................................................... In

Atkins v. Virginia,

536 U.S. 304, 317 (2 0 0 2 ) ............................ 5, 16, 17, 18

Batson v. Kentucky,

476 U.S. 79 (1 9 8 6 ) ..............................................................In

City o f Los Angeles v. Lyons,

461 U.S. 95 (1 9 8 3 ) ........................................................... 7n

Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1 9 7 2 ) ..................................................In, 15

Gregg v. Georgia,

428 U.S. 153 (1 9 7 6 ) ......................................................... 15

Ham v. South Carolina,

409 U.S. 524 (1 9 7 3 ) ........................................................... In

Lockett v. Ohio,

438 U.S. 586 (1 9 7 8 ) ................................................. 16, 17

McCleskey v. Kemp,

481 U.S. 279 (1 9 8 7 ) ........................................................... In

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Miller-El v. Cockrell,

537 U.S. 322 (2 0 0 3 ) ........................................................ In

State ex rel. Simmons v. Roper,

112 S.W .3d 397 (Mo. 2 0 0 3 ) ........................................ 18n

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 ( 1 9 6 5 ) .......................... In

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1 9 1 0 ) .......... 15-16

Other Authorities:

A nthony A m sterdam et al.,

Amicus Brief, Court o f Appeals o f the

State o f New York, People o f the State

o f New York Against Darrel K. Harris,

27 N.Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc.Change 399 (2002) . . 11-12

D avid C. Baldus et al.,

How the Death Penalty Works: Empirical

Studies o f the Modem Capital Sentencing

System, 83 Cornell L. Rev. 1638 (1998) ................. 17n

R ick Bragg,

DNA Clears Louisiana Man on Death Row,

Lawyer Says, N.Y. Times, Apr. 22, 2003, at A 14 . 13n

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

Bureau o f Justice Statistics,

U.S. D ep’t of Justice, Contacts Between

Police and the Public: Findings from the

1999 National Survey 2 (2001), available

at http://w w w .ojp.usdoj.gov /bjs/pub/pdf/

c p p 9 9 /p d f ..................................................................... 6n-7n

Jeffrey Fagan & G arth Davies,

Street Stops and Broken Windows:

Terry, Race and Disorder in New York

City, 28 Fordham Urb. L. J. 457 (2 0 0 0 ) ...................... 7n

Gwen Filosa,

Ex-Death Row Inmate Home on Bond,

Tim es-Picayune, June 23, 2004 ................................. 14n

Sam uel R. Gross et al.,

Exonerations in the United States 1989

Through 2003 (Apr. 19, 2004), available at

http://w w w .law .um ich.edu/N ew sA ndInfo/

ex o n era tio n s-in -u s.p d f...........................................11, 17n

Bob Herbert,

Trapped in the System, N .Y . Times,

July 14, 2003, at A 1 7 .................................................... 14n

M arc M auer,

Race to Incarcerate ( 1 9 9 9 ) ............................................. 7n

http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov

http://www.law.umich.edu/NewsAndInfo/

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

N ew York City Police Department,

City wide Stop and Frisk Data: 1998, 1999,

and 2000, available at http://ww w.nyc.gov/

htm l/nypd/pdf/pap/stopandfrisk_0501.pdf.................6n

Note,

Developments in the Law: Race and the

Criminal Process, 101 Harv. L. Rev. 1472 (1988) . 7n

K enneth B. Nunn,

The Child as Other: Race and Differential

Treatment in the Juvenile Justice System,

51 DePaul L. Rev. 679 ( 2 0 0 2 ) ...................................... 8n

Office o f Juvenile Justice and Delinquency

Prevention,

Office o f Justice Programs, U.S. D ep’t

o f Justice, Juveniles in Corrections 12

(June 2004), available at http://ww w.ncjrs.org/

pdffiles 1 /ojjdp/2028 85 .p d f .................................7, 8n, 9n

Office o f Juvenile Justice and Delinquency

Prevention,

Office of Justice Programs, U.S. D ep’t

o f Justice, Minorities in the Juvenile

Justice System 2 (Dec. 1999), available at http://

w w w .ncjrs.org/pdffilesl/ojjdp/179007.pdf . . . . 8n, 9n

http://www.nyc.gov/

http://www.ncjrs.org/

http://www.ncjrs.org/pdffilesl/ojjdp/179007.pdf

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

M arc Riedel,

Discrimination in the Imposition o f the

Death Penalty: A Comparison o f the

Characteristics o f Offenders Sentenced

Pre-Furman and Post-Furman, 49 Temp.

L.Q. 261 ( 1 9 7 6 ) .............................................................. 12n

David A. Sklansky,

Traffic Stops, Minority Motorists and the

Future o f the Fourth Amendment, 1997

Sup. Ct. Rev. 271 ( 1 9 9 7 ) ................................................ 6n

V ictor L. Streib,

The Juvenile Death Penalty Today: Death

Sentences and Executions fo r Juvenile Crimes,

January 1, 1973 - June 30, 2004, available at

http ://w w w . law. onu . edu/faculty/streib/

docum ents/JuvD eathJune302004N ew Tables.pdf . lOn

Alan J. Tom pkins etal.,

Subtle Discrimination in Juvenile Justice

Decisionmaking: Social Scientific Perspectives

and Explanations, 29 Creighton L. Rev.

1619(1996) ..........................................................................7

United States General A ccounting Office,

Death Penalty Sentencing: Research Indicates

Pattern o f Racial Disparities 2 (Feb. 1990) . . 12n,13n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

B ela A ugust W alker,

Note, The Color o f Crime: The Case Against

Race-Based Suspect Descriptions, 103 Colum.

L. Rev. 662 (2003) 6

1

Interest of Amici Curiae1

The N A ACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(LDF), is a non-profit corporation form ed to assist African

Am ericans in securing their rights by the prosecution of

lawsuits. Its purposes include rendering legal aid without

cost to A frican Am ericans suffering injustice by reason o f

race w ho are unable, on account o f poverty, to employ legal

counsel on their own. For many years, its attorneys have

represented parties and it has participated as amicus curiae

in this Court, in the low er federal courts, and in state courts.2

The Am erican Civil Liberties U nion (ACLU) is a

nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with more

than 400,000 m em bers dedicated to the principles of liberty

and equality em bodied in the Constitution. It has two

regional affiliates in M issouri: the A C LU of Kansas &

W estern M issouri, and the ACLU o f Eastern M issouri. The

A C LU has long supported abolition o f the death penalty as

'Letters of consent by the parties to the filing of this brief have

been lodged with the Clerk of this Court. No counsel for any party

authored this brief in whole or in part, and no person or entity

other than amici made any monetary contribution to the

preparation or submission of this brief.

2The LDF has a long-standing concern with the influence of

racial discrimination on the criminal justice system in general,

and on the death penalty in particular. We therefore represented

the defendants in, inter alia, Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238

(1972) , McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987), Swain v.

Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965), Alexander v. Louisiana, 405

U.S. 625 (1972) and Ham v. South Carolina, 409 U.S. 524

(1973) and appeared as amicus curiae in Batson v. Kentucky,

476 U.S. 79 (1986) and Miller-El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322

(2003).

2

a form o f cruel and unusual punishm ent. It has also long

believed that the death penalty is adm inistered in this country

in a manner that is both arbitrary and discrim inatory. These

concerns prom pted the creation o f the A C L U ’s Capital

Punishm ent Project, and this case once again brings those

concerns into sharp focus. The question o f w hether juveniles

can be executed by the state is thus one o f substantial

im portance to the A C LU and its members.

The National Association o f Crim inal D efense Lawyers

(NACDL) is a non-profit corporation with m ore than 10,000

members nationwide and 28,000 affiliate m em bers in 50

states, including private crim inal defense lawyers, public

defenders and law professors. The A m erican Bar

Association recognizes N A CD L as an affiliate organization

and awards it full representation in its H ouse of Delegates.

NACDL was founded in 1958 to prom ote study and research

in the field o f crim inal law , to dissem inate and advance

knowledge o f the law in the area o f crim inal practice, and to

encourage the integrity, independence, and expertise o f

defense lawyers in crim inal cases. N A CD L seeks to defend

individual liberties guaranteed by the Bill o f Rights and has

a keen interest in ensuring that legal proceedings are handled

in a proper and fair manner. A m ong N A C D L ’s objectives is

promotion o f the proper adm inistration o f justice.

The National Bar Association, the N ation’s oldest and

largest bar association o f color, was founded in 1925. One

of its m issions is to prom ote social justice and equality. Its

m em bership is comprised o f a netw ork o f 18,000 law yers,

judges and legal scholars w ho have developed a substantive

interest and expertise in the juvenile justice area.

The National Urban League Institute for O pportunity and

Equality is dedicated to the pursuit o f equal opportunity for

3

African Am ericans and concentrates on crim inal justice,

em ployment and workforce development, education, housing

and economic and comm unity developm ent.

The National Black Police A ssociation (NBPA), which

represents approxim ately 35,000 individual m em bers and

m ore than 140 chapters, is a nationw ise organization of

African Am erican Police Associations dedicated to the

prom otion o f justice, fairness and effectiveness o f law

enforcement.

The National Conference o f B lack Lawyers (NCBL), a

legal organizations that employs its m em bers’ skills in the

m ovem ent against racism and for the liberation o f African

peoples, seeks to protect hum an rights, achieve self-

determ ination o f A frican comm unities, and w ork in coalition

to assist to assist in ending the oppression o f all peoples.

The National Black Law Students Association (NBLS A),

which represents over 6,000 B lack students at law schools

across the country, endeavors to sensitize the law and legal

profession to the ever-increasing needs o f the Black

community.

All amici have a substantive interest in juvenile justice

and oppose the execution o f juvenile offenders because the

sentencing and execution o f young offenders is plagued by

the same racial bias that each group strives to eliminate.

Amici believe their perspectives on how race inappropriately

influences capital prosecutions against juvenile offenders

differs from the im m ediate concerns o f the parties and will

be valuable to the Court in appraising the issues presented.

4

Summary of Argument

This Court has long sought to ensure that the death

penalty is adm inistered with channeled discretion, that

decisionm akers consider and give effect to relevant factors

counseling against death, and that arbitrary factors, such as

race, do not dictate the outcom e o f life or death decisions.

By steadfastly guarding these principles, this C ourt has

endeavored to achieve a fair and color-blind death penalty.

D espite this C ourt’s efforts to excise race from the capital

punishm ent calculation, it rem ains a pivotal factor in the

administration of the juvenile death penalty. Decisionm akers

— e.g., prosecutors and juries — are legally precluded from

relying explicitly on race when exercising their discretion

and deciding whether, and to what extent, a defendant’s

youth weighs against a decision to seek or to im pose a death

sentence. But in practice, race rem ains a critical

consideration. Specifically, empirical evidence suggests that

for offenders of color, decisionm akers discount or altogether

elim inate the m itigating value o f youth. Thus, currently

death-sentenced juveniles as well as juveniles who have been

executed are predom inantly youth o f color.

Em pirical evidence likewise dem onstrates that young

offenders o f color are m ore likely than juvenile defendants

generally to be wrongfully convicted, w rongly sentenced to

death, and wrongfully subjected to an otherw ise flawed

adjudication. M uch m ore than a m ajority o f both exonerated

juveniles and of exonerated juvenile offenders who had been

prosecuted on the basis o f false confessions are adolescents

o f color.

B ecause race continues to constrain the discretionary

consideration of youth as a m itigating factor and increases

the risk that juvenile offenders o f color will receive a death

5

sentence, this Court should categorically exclude juveniles

from death penalty eligibility.

ARGU M EN T

Introduction

The question presented by this case is w hether the death

penalty is constitutionally disproportionate for juvenile

offenders. For the reasons outlined in Respondent’s brief and

the briefs o f numerous other supporting amici, the answer to

that question is certainly “yes.” This brief is being submitted

to highlight the fact that race improperly continues to

dim inish (and often to eliminate) the m itigating value of

youth at the various points o f discretion in capital

prosecutions against juvenile offenders and thereby

“underm ine[s] the strength of the procedural protections that

our capital jurisprudence steadfastly guards.” Atkins v.

Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 317 (2002).

The process for determining how, if at all, to factor youth

into the calculus when deciding whether to charge,

prosecute, try and sentence juvenile offenders to death is

unavoidably subjective and standardless. Even bifurcated

sentencing hearings fail to provide m eaningful direction

because the sentencer is not provided with any guidelines for

determ ining whether and to what extent a defendant’s youth

is to be considered a m itigating factor. This absence of

structure denies capitally charged juvenile offenders the

necessary protection against the influence o f im proper

considerations, such as race, in these critical death penalty

decisions. In light o f this dilemm a, this Court should hold

that the death penalty for juvenile offenders is

6

unconstitutional and disproportionate, and that it violates the

E ighth Am endm ent.

Race in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Systems

Em pirical evidence has repeatedly dem onstrated that

w ithin the crim inal justice system,

[d isp roportionate burdens on people o f color em erge

at each point that discretion is used: whether it be the

decision to detain a suspect, to m ake a traffic stop, to

search a driver, to shoot at a civilian, to handcuff a

suspect, to m ake an arrest, to prosecute a case, to try

a m inor defendant as an adult, to increase charges, to

p lea bargain, to convict, to determ ine sentence

length, or ultim ately w hether to apply the death

penalty or not. Each step in the crim inal process

increases the discrim inatory effect, as well as the

perceived im age o f m inorities as disproportionately

crim inal.

Bela A ugust W alker, Note, The Color o f Crime: The Case

Against Race-Based Suspect Descriptions, 103 Colum. L.

Rev. 662, 680-81 (2003) (footnotes om itted).3

’Among the works cited by the author, see, inter alia, New

York City Police Department Citywide Stop and Frisk Data:

1998, 1999, and 2000, at 1, available at http://www.nyc.

gov/html/nypd/pdf/pap/stopandfrisk_0501.pdf (citing NYPD

records indicating that approximately one half of stop and frisk

suspects during 1998-2000 period were black); David A.

Sklansky, Traffic Stops, Minority Motorists and the Future o f the

Fourth Amendment, 1997 Sup. Ct. Rev. 271, 313 (1997) (citing

data from Florida, New Jersey, and Maryland to show that

“minority motorists are pulled over far more frequently than

whites”); Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Dep’t of Justice,

Contacts Between Police and the Public: Findings from the 1999

http://www.nyc

7

The same phenom enon occurs w ithin the juvenile justice

system. In juvenile justice, “discretionary decisionmaking,

w hich necessarily utilizes substantive factors [such as the

juven ile ’s personal and social environment, and his/her

situation at hom e, in the com m unity and in school], serves to

facilitate disproportionately adverse outcomes for minorities,

particularly A frican A m ericans.” Alan J. Tom pkins et al.,

Subtle Discrimination in Juvenile Justice Decisionmaking:

Social Scientific Perspectives and Explanations, 29

Creighton L. Rev. 1619, 1631 (1996). Thus, the U.S.

D epartm ent o f Justice, Office o f Juvenile Justice and

Delinquency Prevention has found that “ [bjlack juveniles are

overrepresented at all stages o f the juvenile justice system

National Survey 2 (2001), available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov

/bjs/pub/pdf/cpp99/pdf (“During the traffic stop, police were more

likely to carry out some type of search . . . on a black (11.0%) or

Hispanic (11.3%) than a white (5.4%).”); id. at 16 (“Blacks

(6.4%) and Hispanics (5.0%) were more likely than whites (2.5%)

to be handcuffed.”); Note, Developments in the Law: Race and

the Criminal Process, 101 Harv. L. Rev. 1472, 1495 (1988) (“[A]

black citizen today is far more likely than is a nonblack citizen to

be shot or seriously injured by a police officer.”); City of Los

Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95, 116 n.3 (1983) (Marshall, J.,

dissenting) (“[I]n a city where Negro males constitute 9% of the

population, they have accounted for 75% of the deaths resulting

from the use of chokeholds.”); Jeffrey Fagan & Garth Davies,

Street Stops and Broken Windows: Terry, Race and Disorder in

New York City, 28 Fordham Urb. L. J. 457,491 (2000) (“[S]top-

to-arrest ratio of blacks (7.3 stops per arrest) is 58.7% higher than

the ratio for non-Hispanic whites (4.6).”); Marc Mauer, Race to

Incarcerate 125 (1999) (“[Statistical analysis by the United

States Sentencing Commission concluded that, for comparable

behavior, whites were being offered plea bargains leading to

outcomes falling below the level requiring a mandatory minimum

sentence more often than blacks or Hispanics.”).

http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov

8

com pared with their proportion to the population .”4

S p e c i f i c a l l y , A f r i c a n - A m e r i c a n c h i l d r e n a r e

disproportionately represented in the num ber o f juvenile

arrests,5 are overrepresented among children w ho are

detained,6 are more likely to have form al delinquency

petitions filed against them than their white counterparts,7 are

m ore likely to have their cases transferred into adult court for

prosecution,8 are “m ore likely to be placed in public secure

4Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention,

Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Juveniles in

Corrections 12 (June 2004), available at http://www.ncjrs.org

/pdffiles 1 /ojj dp/202885 .pdf [hereinafter Juveniles in Corrections\.

5Kenneth B. Nunn, The Child as Other: Race and Differential

Treatment in the Juvenile Justice System, 51 DePaul L. Rev. 679,

683-84 (2002) (noting that, in 1997, while black youth accounted

for only 15% of the under-eighteen population in the United

States, they represented 26% of the juvenile arrests and 31 % of

the delinquency cases referred for prosecution).

6Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention,

Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Minorities in

the Juvenile Justice System 2 (Dec. 1999), available at

http://www.ncjrs.org/pdffilesl/ojjdp/179007.pdf [hereinafter

Minorities] (“In 1996-97, while 26% of juveniles arrested were

black, [blacks] made up 45% of cases involving detention.

Thirty-two percent of adjudicated cases involved black youth, yet

40% of juveniles in residential placement are black. Even

recognizing the overrepresentation of black juveniles involved in

violent crimes reported by victims (39%), they still accounted for

a disproportionate share of juvenile arrests for violent crimes

(44%) and confinement (45%).”).

7Nunn, supra, at 685.

Id. at 685-86.

http://www.ncjrs.org

http://www.ncjrs.org/pdffilesl/ojjdp/179007.pdf

9

facilities, while white youth are more likely to be housed in

private facilities or diverted from the juvenile justice

system ,”9 are “more likely . . . to be confined behind locked

doors,” 10 and “are . . . held in custody longer than white

youth.” 11

Race Influences Capital Sentencing

Decisions in Cases Involving Juveniles

The above evidence of racial discrim ination w ithin the

juvenile and criminal justice systems has significant

im plications for this C ourt’s — and our N ation’s —

aspiration to achieve unbiased capital sentencing, including

in juvenile cases. Decisions whether to charge a juvenile

w ith a capital offense, whether to offer a juvenile a non

death p lea bargain, and whether to im pose a death sentence

on a juvenile offender, take place w ithin the context o f a

system in which race is deeply ingrained. Because there are

no standards governing whether and to what extent youth

should factor into these decisions, there is a significant

possibility, if not probability, that an offender’s race will

influence, if not dictate, that determination. This is so even

though at every stage at which a decisionm aker m ust

9Minorities, supra, at 3. See also Juveniles in Corrections,

supra, at 10 (finding that, in 1999, “[mjinorities accounted for

66% of juveniles committed to public facilities nationwide - a

proportion nearly twice their proportion of the juvenile

population”).

10 Id. at 17. See also Minorities, supra, at 9 (“Secure

detention was nearly twice as likely in 1996 for cases involving

black youth as for cases involving whites, even after controlling

for offense.”).

"Nunn, supra, at 687.

10

exercise his/her discretion for or against a death sentence

(e.g., the point at which a prosecutor files a capital charge

and/or when the trial factfinder m akes its sentencing

determ ination), the decisionm aker is prohibited from

explicitly considering race. The em pirical evidence

dem onstrates that race continues to m atter, presum ably

because decisionm aker(s) in the capital system often fail to

exclude conscious or unconscious racial considerations from

the subjective, standardless, and unreview ed process o f

deciding w hether an individual defendant’s youth is

sufficiently m itigating to w arrant leniency.

A vailable data regarding the adm inistration o f the death

penalty for juvenile offenders supports this conclusion. As

o f June 30, 2004, there w ere 72 juveniles under sentence o f

death in the U nited States.12 Two thirds are teenagers o f

color.13 (In addition, two thirds o f the victim s o f the death-

sentenced adolescents are w hite.14) Over half o f the

juveniles who were executed since 1973 were black or

L atino .15 A nd significantly m ore adolescents o f color have

12Victor L. Streib, The Juvenile Death Penalty Today: Death

Sentences and Executions for Juvenile Crimes, January 1,1973 -

June 30, 2004, at 12 tbl.5, at http://www.law.onu.edu

/faculty/streib/documents/JuvDeathJune302004NewTables.pdf.

13See id. Twenty-nine of these offenders are African-

American, 15 of them are Latino, 1 is Native American and 2 are

Asian. Id.

,4See id. One Native American, 7 Asians, 8 Blacks, 11

Latinos and 65 whites were the victims of these death sentenced

juvenile offenders. Id.

X5See id. at 4 tbl.l. Eleven of the twenty-two executed

juveniles were African-American and one was Latino. Id.

http://www.law.onu.edu

11

been found to have been wrongly convicted o f rape and

m urder than white adolescents: A study o f exonerations

occurring betw een 1989 and 2003 revealed that ninety

percent o f exonerated juveniles were A frican-A m erican or

L atino .16

[Although] w hite defendants account for 34% of all

m urder exonerations and 27% o f all rape

exonerations — [they represent] only 14% ofjuvenile

m urder exonerations, and not a single juvenile rape

exoneration. A m ajority o f the teenagers arrested for

these two crimes are white — 62% o f all juvenile

rape arrests in 2002, and 46 % o f juvenile m urder the

relevant time period .17

This pattern of race lim iting (or eviscerating) the

m itigating value of youth at the point o f prosecutor, judge

and/or ju ry discretion, is consistent with the em pirical

evidence docum enting the fact that race continues to

influence capital prosecutions generally. D ata reveals that

[n]one o f the statutes upheld by Gregg [v. Georgia,

428 U.S. 153 (1976)] and its progeny as formally

sufficient to cure the Furman arbitrariness/

discrim ination problem have come close to

elim inating it. To the contrary, capital sentencing

decisions under the so-called “guided discretion” type

o f statute sustained in Gregg . . . have consistently

been found to turn prim arily on the race o f the victim

l6See Samuel R. Gross et al., Exonerations in the United

States 1989 Through 2003, at 24 tbl.6 (Apr. 19, 2004), available

at http ://www.law.umich.edu/NewsAndInfo/exonerations-in-us.

pdf.

17Id. at 34 (emphasis in original).

http://www.law.umich.edu/NewsAndInfo/exonerations-in-us

12

and secondarily on the race o f the defendant, usually

in combination.

Anthony A m sterdam et al., Amicus Brief, Court o f Appeals

o f the State o f New York, People o f the State o f New York

Against Darrel K. Harris, 27 N .Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc. Change

399,442-43 (2002) (footnotes om itted).18 Thus, for example,

in 1990, the United States General A ccounting Office issued

a R eport to the Senate and House Com m ittees on the

Judiciary evaluating 28 separate studies o f the death penalty

from various regions o f the country.19 That report concluded

that the studies “show[] a pattern o f evidence indicating

racial disparities in the charging, sentencing, and im position

18“Looking at the 493 people who had been on death rows in

28 States just before Furman was decided and then at the 407

people sent to death rows in the same 28 States during their first

three years of operating under post-Furman statutes, this study

found that the percentage of nonwhite death row inmates had

actually risen, from 53% to 62%-----Although more than half of

the nation’s murder victims in the post-Furman period were

nonwhite, 87% of the victims of the persons condemned to die in

States selected to compare mandatory-death-sentence

jurisdictions with guided-discretion jurisdictions were white.”

Amsterdam, supra, at 442 n.143 (citing Marc Riedel,

Discrimination in the Imposition of the Death Penalty: A

Comparison of the Characteristics of Offenders Sentenced Pre-

Furman and Post-Furman, 49 Temp. L.Q. 261 (1976)); see also

id. at 443 n.147 (citing articles establishing the fact that race

influences the exercise of prosecutorial discretion to seek a death

sentence or to refuse a noncapital disposition).

19United States General Accounting Office, Death Penalty

Sentencing: Research Indicates Pattern of Racial Disparities 2

(Feb. 1990).

13

of the death penalty after the Furman decision.”20

Review o f one juvenile capital case provides a concrete

illustration o f how discretionary decisions that may be

influenced by race can have a detrim ental im pact on the

capital punishm ent process in cases involving young

defendants.

Ryan M atthews is an African-A m erican young man. In

1999, Ryan M atthews was charged with, convicted of, and

sentenced to death for a Louisiana m urder he allegedly

com m itted when he was seventeen years old. Ryan

M atthews, like the m ajority o f death-sentenced juveniles,

was convicted o f m urdering a white victim . A jury

com posed o f 11 whites and one black found him guilty

notw ithstanding questionable identification testim ony,21 the

absence o f physical evidence connecting Ryan M atthew s to

20Id. at 5. The GAO Report concluded that “[i]n 82 percent

of the studies, race of victim was found to influence the likelihood

of being charged with capital murder or receiving the death

penalty, i.e., those who murdered whites were found to be more

likely to be sentenced to death than those who murdered blacks.”

Furthermore, the GAO study found that “[t]he evidence for the

race of victim influence was stronger for the earlier stages of the

judicial process (e.g., prosecutorial discretion to charge a

defendant with a capital offense, decision to proceed to trial rather

than plea bargain) than in later stages.” Id.

21Rick Bragg, DNA Clears Louisiana Man on Death Row,

Lawyer Says, N.Y. Times, Apr. 22, 2003, at A14 (“One witness

said he had pulled his car in front of the robber’s car and

fishtailed for a while so it could not get past him. The witness

said that as he was dodging bullets from the gunman, he saw the

gunman’s face clearly in the rearview mirror. Another witness

said she had seen Mr. Matthews briefly pull up the mask in the

store while she was in the parking lot.”).

14

the m urder, and the inconsistencies betw een the witness

statem ents and the physical evidence.22 The same ju ry

sentenced Ryan M atthews to death.

In 2003, after another prisoner bragged o f having

com m itted the m urder for which Ryan M atthew s was

convicted, DNA testing was conducted. Those tests revealed

that D N A found in saliva and a skin cell w hich were left on

the ski m ask worn by the killer did not m atch the D N A of

Ryan M atthews. Instead, it m atched the D N A o f the

bragging prisoner — a convicted drug dealer and m urderer.

Ryan M atthew s’ conviction was then vacated and a n e w trial

was ordered. He was released from prison on bond and is

now aw aiting re-trial.23

Given the dearth of credible evidence regarding guilt, it

w ould have been reasonable to expect that Ryan M atthew s’

youth would, at the very least, have dim inished the

likelihood that a death sentence would be sought or imposed.

22“Witnesses said the masked gunman had dived through the

open car window, but the window on the Grand Prix the police

believe was the getaway car [the car in which Mr. Matthews was

apprehended] had been stuck closed for as long as anyone could

remember.” Id. Additionally,

[e]yewitnesses had said the gunman in the convenience

store was not very tall, perhaps 5-5 or 5-6, and of medium

build. Sheree Falgout, who was standing at the register

when the proprietor was gunned down, recalled telling the

police that the assailant ‘was not a large person.’ Other

witnesses concurred. Ryan Matthews is 6 feet tall.

Bob Herbert, Trapped in the System, N.Y. Times, July 14, 2003,

at A17.

23See Gwen Filosa, Ex-Death Row Inmate Home on Bond,

Times-Picayune, June 23, 2004.

15

It did not. And, although“[w]e cannot say from facts

disclosed in [the] record[] that [this] defendan t] [was]

sentenced to death because [he was] black "Furman v.

Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 ,253 (1972) (Douglas, concurring), it

is equally im possible to discount the possibility that race

played a constitutionally inappropriate role in the ultimate

decision to seek and im pose the death penalty. In light o f all

o f the o ther factors counseling against the execution of

juvenile offenders, such individuals should not, in addition,

be com pelled to face the risk of racial bias in the capital

punishm ent process.

The Only Way to Insure that Race Does Not

Determine Whether a Juvenile Defendant Will

Receive a Death Sentence Is to Hold that the

Death Penalty May No Longer Be Imposed

Upon Juveniles

In 1972, this Court announced, in Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972), that any law which allowed an arbitrary

and illegitim ate factor such as race to play a role in the

adm inistration o f the death penalty is unconstitutional. See

id. at 249-57 (Douglas, J., concurring), 274-77, 293-96 &

n.48 (Brennan, J., concurring), 309-10 & n.13 (Stewart, J.,

concurring), 312-14 (W hite, J., concurring), 363-66 & n . 152

(M arshall, J., concurring). W hile the death penalty laws

have been changed to lim it sentencer discretion, see Gregg

v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976), race continues to play an

invidious role in the administration o f capital punishm ent for

juvenile offenders. The death penalty for such offenders is,

therefore, unconstitutional.

The Eighth A m endm ent’s prohibition on excessive

sentences requires the “punishm ent for crim e [to] be

graduated and proportioned to [the] offense.” Weems v.

16

United States, 217 U.S. 349, 367 (1910). In analyzing

whether capital punishm ent is constitutionally proportional

for specific categories o f offenders, this Court has considered

whether the offenders at issue have a characteristic w hich

underm ines the crim inal justice system ’s capacity for

effective adjudication. Thus, for example, w hen this C ourt

decided that the Eighth A m endm ent prohibits the execution

o f mentally retarded offenders, it held that

[t]he risk “that the death penalty will be im posed in

spite of factors w hich m ay call for a less severe

penalty,”is enhanced, no t only by the possibility o f

false confessions, but also by the lesser ability o f

m entally retarded defendants to m ake a persuasive

showing o f m itigation in the face o f prosecutorial

evidence o f one or m ore aggravating factors.

M entally retarded defendants m ay be less able to give

m eaningful assistance to their counsel and are

typically poor w itnesses, and their dem eanor m ay

create an unw arranted im pression o f lack o f rem orse

for their crimes. As Penry dem onstrated, m oreover,

reliance on m ental retardation as a m itigating factor

can be a tw o-edged sw ord that m ay enhance the

likelihood that the aggravating factor o f future

dangerousness will be found by the jury.

Atkins, 536 U.S. at 320-21 (quoting Lockett v. Ohio, 438

U.S. 586, 605 (1978)) (footnote om itted).

Youth o f color in capital cases face m eaningfully

identical circum stances. For m any juvenile offenders, race

devalues evidence that would otherw ise support a case for

life, encourages the im position o f the death penalty in spite

o f the existence o f factor(s) w hich should call for leniency

and ultim ately functions as an unlaw ful im pedim ent to the

17

proper consideration o f m itigating evidence. “W hen the

choice is betw een life and death, that risk is unacceptable

and incom patible with the com m ands o f the Eighth and

Fourteenth A m endm ents.” Lockett, 438 U.S. at 605.

One specific way in which race increases the likelihood

that the death penalty will be im posed on a juvenile offender

notwithstanding the existence o f significant factors calling

for leniency is that youth of color, like offenders w ith mental

retardation, are m ore likely to offer false confessions. As

detailed in other briefs before this Court, this is true for

juveniles in general. Em pirical evidence reveals, however,

that this likelihood o f falsely confessing is even greater when

the youth at issue is a person o f color. The G ross study of

rape and m urder exonerations betw een 1989 and 2003,

revealed that “[e] ighty-five percent o f the juvenile exonerees

who falsely confessed were African A m erican.”24 Thus, race

combines w ith age to render capitally charged juveniles

particularly vulnerable to false confessions and wrongful

convictions. The com bination thereby enhances “[t]he risk

‘that the death penalty will be im posed in spite o f factors

which m ay call for a less severe penalty .’” Atkins, 536

U .S .at 320-21 (quoting Lockett, 438 U.S. at 605).

Additionally, as with mental retardation, the combination

o f race and youth functions as a “double-edged sword,”

increasing the likelihood that a sentencer w ill perceive the

defendant as a future danger. W hen the offender is a young

person of color, the ju ry may be conditioned to think o f the

offender as “the other” and dangerous (especially if the

victim is w hite).25 The youthfulness o f the offender causes

24Gross, supra, at 25 (emphasis added).

25See, e.g., David C. Baldus et al., How the Death Penalty

Works: Empirical Studies of the Modem Capital Sentencing

18

the ju ry to think that this defendant is m ore likely to get out

o f prison and is, therefore, m ore likely to pose a future

danger to society.26 Com bined these factors undoubtedly

cause the ju ry to lean in favor o f the death penalty. Race

together w ith youth is, therefore, a com bination w hich is

often perceived by factfinders as aggravating when, in fact,

it can and should be perceived as m itigating.

Because youth combines w ith race in a w ay that

“underm ine[s] the strength o f the procedural protections that

our capital jurisprudence steadfastly guards,” Atkins, 536

U.S. at 317, and because, as a result, youth o f color “in the

aggregate face a special risk o f w rongful execution,” id. at

321, it is appropriate for this Court to issue “a categorical

rule m aking such offenders ineligible for the death penalty.”

Id. at 320.

System, 83 Cornell L. Rev. 1638 (1998) (finding that in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, African-American capital defendants

faced substantially increased odds of receiving the death penalty

as compared to similarly situated white defendants and that being

African American increased the odds of receiving a death

sentence to the same extent as did the presence of the additional

aggravating circumstances of torture or grave risk of death).

26Indeed, in Christopher Simmons’ case, the prosecution

argued that the jury should consider Mr. Simmons’ age as an

aggravator instead of a mitigator in that it rendered him more

likely to be a future danger to society. State ex rel. Simmons v.

Roper, 112 S.W.3d 397, 413 (Mo. 2003)

19

Conclusion

The judgm ent below should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Steven R. Shapiro

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

125 Broad Street

New York, NY 10025

(212) 549-2500

Diann Y. Rust-Tierney

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

915 15th Street, N.W.

W ashington, DC 20005

(202) 675-2321

Barry C. Scheck

President Elect

National Association

of Criminal Defense

Lawyers

Cochran, Neufeld &

Scheck

99 Hudson Street, 8th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-9380

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Miriam Gohara

*Christina A. Swarns

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund,

Inc.

99 Hudson Street,

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

Clyde E. Bailey, Sr .

President

National Bar

Association

1225 11th Street, N.W.

Washington, DC 20001

(202) 842-3900

Charles J. Hamilton, Jr .

Paul, Hastings,

Janofsky

& Walker LLP

75 East 55th Street

New York, NY 10022

(212)318-6000

20

Gilda Sherrod-Ali

National Conference of

Black Lawyers

116 West 11 1th Street

New York, NY 10027

(866) 266-5091

* Counsel of Record

* Counsel for Amici Curiae