Research Memorandum on Bozeman and Wilder v. State 1

Working File

January 1, 1981 - January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Research Memorandum on Bozeman and Wilder v. State 1, 1981. 3c79bbfa-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8a3f568e-f3fc-4cec-a3f2-ba8df5e335b1/research-memorandum-on-bozeman-and-wilder-v-state-1. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

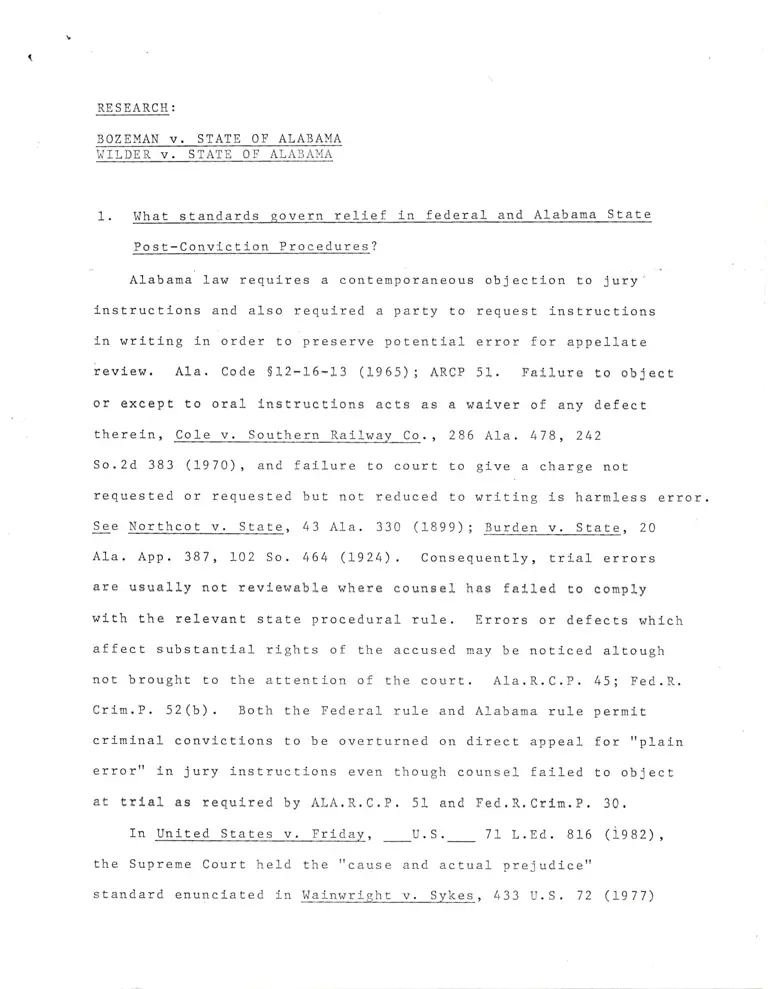

RESEARCH:

BOZEMAN v. STATE 0F ALABAMA

WILDER v. STATE OF ALABAMA

1. What st,andards govern relief in federal and Alabama StaEe

Post-Convlction Procedures ?

Alabama Iaw requires a contemporaneous obJection to Jury'

lnstructlons and also required a party to request instructj-ons

ln writlng in order to preserve potential error for appellate

revlew. A1a. code s 1.2-r6-13 (19 65) ; ARcP 51. FalJ.ure to obJ ecr

or except to oral lnstructLons acts as a walver of any defect

therein, Cole v. Southern Railway Co., 286 Ala. 478, 242

So.2d 383 (L970), and fallure to court Eo give a charge not

requested or requested but not reduced to writing is harmless error.

See Northcot v. State, 43 Ala. 330 (1899); Burden v. Stare, 20

ALa. App. 387, I02 So. 464 (L924). Consequenrly, trlal errors

are usually not revle\{abl.e where couneel has falLed to comply

wlth the reLevant state procedural ru1e. Errors or defects which

affect substantlal- rights of Ehe accused may be noticed altough

not brought to the attention of the court. Ala.R.C.P. 45; Fed.R.

Crlm.P. 52(b). Both the Federal rule and Alabama rule permit

eriminal- convictions to be overEurned on di.rect appeal for "p1ain

error" in jury instructions even though counsel faiLed to object

at tr{aL as requlred by ALA.R.C.P. 51 and Fed.R.Crln.P. 30.

In United States v. Frj-day, _U.S._ 71 L.Ed. 815 (i982),

the Supreme Court held the "cause and actual prejudicett

standard enunclated in Wainwright, v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72 (L977)

governs relj.ef on collateral attack following procedural de-

f.auLt al trial-. In drawing thls conclusion the Court noted

that where counsel has had an opportunity to object to instruct-

ions at trlaL and on direct appeaL, but failed to do 8or a

colLateraL chal-l-enge may not do service f or an appeal. " Frady,

supra; SE,e.g., E!f_U:[., 368 U.S. 424,428-429 (L962).

Thus, the ttpLain errortt standard only governs reLief on direct

appeaL from errors not obJected to at trlaL.

To obtai.n f ederal-colLateraL relief , the petltloner must

demonstratei (1) cause excuslng the procedural default snd;

(2) actuaL prejudice resulting from compl-ained errors. Frady.

The FederaL Habeas Corpus ManuaI for Capital Cases Llsts arguments

for showing cause and prejudice (pg. 407). In Lhe case of

WlLder and Bozeman cause for failure to request special lnstruct-

Lons as requlred by SL2-L6-13 41a. Code 1975 may be established

by asserrtne lneffecrive aeslsrance of' counB"l:)tl:tllilotleh

actual preJudlce the compLained error by ltseIf rnust have so

infected the entire trlal that the resul-ting convictj-on vlolates

due process. Henderson v. Kibbe, 431 U.S. L45, L54, 52 L,Ed.2d

203 (1-977). Several arguments establishing actual prejudice may

apply to the factual circumstances in the Wilder and Bozeman cases.

The arguments set out in the Federal Habeas Corpus ManuaL (p. 42L-

425) are as follows: (1) under the clrcumstances there was a

ttreasonabl-e posslbll-ity" that the error lnfluenced the verdLct

of the trier of fact. See Chapman v. California,3B5 U.S.18,

24, 25-26 (L967) where prosecut,orial comment on petitioner

not taking the stand was not harmless error; (2) when the tainted

evidence is excluded, the evidence of guilt at trial was not

-2-

Itorierwhelmingttso that the error cannot with certainty be said.

Eo be harmless beyond a reasonabre doubt. E.g., chapman v.

califo.rnia, supra ar 24 (L977); (3) buE for rhe rainr,ed evldence

a 'rrational j urortt could not have f ound the petitioner guilty be-

yond a reasonable doubt. E.g., coLllns v. Auger, 557 F.2d 1107,

1l-10 (5rh clr. 1978), cerr. dented, 439 u.s. 1r33 (r.979). These

arguments w1l-1 be discussed lnthe sections regarding clrcumstantial

evldence and lmpeachment test,imony.

In Frady the Court dId not consider error in the lnstruction

concarnlnB thc alernanta of the crlme, preJudice per se. The

parti.cuLer ctrcumgtances of each csse must be songldered and the

lnetructlon muBt be vlewed ln the context of the overall charge.

cupp.v. Naughren , 4L4 u. s. 141, L46-L47 (1973) . Frady did nor

preeent any affirmatlve evl-dence of mltlgatlng clrcumstances whlch

would tend to prove lack of malj-ce and thereby a killing from murder

to manslaughter. Al-so, the evidence for the State was substant'lal-

on the questlon of maltce. A jury properly lnsEructed would have

probably reached the Bame concluslon, In Llght of these consldera-

tlons the Court found the instruction resulted in no actual- preju-

dice. In Alabama the I,Irit of Error Coram Nob is provides post-

convlction relLef in the state courEs. A. R. c. p. 60. Generally Ehe

motion is made 1n the court which rendered the judgment. rf the

motion is denied PeEj-tioner appeals to the next court. 'rstate 1aw

must be consulted to determine what types of claims attacking the

c0nvictlon and sent,ence may be ralsed in the post-convlctton

proceedlngs available in a state. rn general, at1 matters that

might possibly r/rarrant federal habeas corpus relief in the

case that were not clearry and exhaustively raised on appeal

-3-

from the conviction and sentence in the State courLs musE be

raised j-n some State post-conviction proceeding Eo assure that

the Federal exhaustion requirement has been met. t' Federal }labeas

corpus Manual .for capital cases, James Liebman, vo1. I, 19Br 2d.

Edltlon, pg. 62, See, Johnson v. wilLiams, 244 A1a. 39L, L2 So.2d

683 (L943) (adopts trirlr of Error Coram Nobis into Alabama Procedure);

GroLe v. State, 48 Ala. App. 7Og (1972) (whether issues ralsed by

appellant are withln purview of error coram nobls proceedings) '

Inllta11y, the wrlt waa avaLlable Eo questlon Procedural lssues

oEher than the rnerlts of the ca6er 8od to ralse errors concerntng

fact8notknowntocourtatthettmeoftrtaI.@,!!!I3,at

394, 395. Alabarna case law since 1943 has narrowed the scope

of the wtrt, to correct, rr'r*'r an error of acts r o11 e nOt apPeAring on

the face of the record, unknown to the Court or parEy affecEed, and,

which if known in time, would have prevented the judgment chall-enged,

and served as a motion for new triat:" the ground of newly dis-

covcrad svldence.rr TlIIle v. State, 349 So.2d 95, 97 (lta' APP'

Le77) ,

Where a collateral attack in federal procedure will- not do

servj.ce for failure to raise issues on direct appeal, Frady,

supra, the tlrit of Error coram Nobis will not provide rellef

where a petitioner had the oPportunity to bring to Ehe attention

of the court the matt,er comPlained of but failed to do so'

Strans v. Un{-E-ed Stat,es., 53 }'.2d 820 (193f ) ' In @'

367 So.2d 542 (A1a.Cr.App. 1978), writ. denled, Ala. 367 So'2d 547 '

defense counsel pettitioned the trial- court by wirt of Error

Coram Nobis, asserting newly discovered evidence and lneffecElve

-4-

assistance of counsel as grounds for a new trial. The writ lras

denled for several reasons. FirsE, the defendant I s failure

to remember the name of an a1lbi witness of the first trial- and

his reco11ectl.on of the name during second trial was considered

newly dlscl-osed evidence but not newJ-y discovered evidence.

The writ hTas noE intended to relieve a party of his own negligence.

Thornburg v. State, 42 ALa. App. 70,152 So.2d 442 (L963).

Second, Ehe alibi wltness provided testimony that was only lm-

peachlng Ln nature Ln that lt cast doubt on part of testlmony

of prosecutlonts wltne6s placlng the defendant near the scene

of the murder. Wlth lmpeachment teetlmony the Jury can elther

accept or rej ect the new witness I s testi-mony and stil1 convict

the defendant. This falls short of the requlrement that the newLy

dlecovered evldonce muec bs euch Es tdtll probafU chengc thg

result tf a new trial 1s granted. Tucke_L v._ State , 57 ALa. App. 15,

325 So.2d 531 (1975), cert. denied, 295 AIa, 430, 325 So.2d 539

(1976). Probably means havlng more evldence for the defendant

than agaJ.nst. Lewls, supra at 545. 0ther requirements f or the

newly discovered evidence include: 1) Ehat it has been discovered

since the trial; 2) that it could not have been discovered before

trial; 3) that it is material to the issue. Finally, counsel \^Ias

not dound to be inadequate. Even though it can be shown thaE an

attorney has made a misEake in the LriaI of a ease Ehat resuLt,s

ln an unfavorable Judgrnent, thls alone 1s not sufflclent to

demonstrate that hls c1lenE has been deprlved of hls constitutional

right to adequate and effecEive representation by counsel. Lee

v. State, 349 So.2d 134 (A1a. Cr. App. , L977) . Even the f ail-ure of

-5-

counsel to make a closJ.ng argument has been held l-nsufficient

to demonstrate j-nadequate representation because this can be a

t,actlcal rr rv€ by couns el-. Rob inson v. State, 361 So. 2d Ll72

(Ala.Cr.App.; Behl- v. State, 405 So.2d 51 (Ata.Cr.App. 198I)

An adequate defense in the context of a constltutional report

to counsel does not mean that counsel will not commit tacti-ca1

errors. Summer v. State, 366 So.2d 336, 341- (ALa. Cr. App. L97B).

Alabama case 1aw on the Writ of Error Coran Nobls embodles a stand-

ard governLng rellef whereby the petltl-oner has a duEy to establlsh

hls right to rellef by "clear, fuJ.1 and satisfactory proof."

Vlncent V. State, 284 ALa. 242, 224 So.2d 50 (1969): "CIear"

is highJ-y exactlng as to proof of facts and always means more than

ttreasonably saELsfylng. " Burden v. State , 52 ALa. App. 348 ' 292

So.2d 463 (L974). The application of this standard seems com-

parable to Ehe "cause and actual prejudicett sEandard set forth "

in Walnwright, supra. See, e.g., Sum*ers.v. Sta.te, 366 So.2d 336

(Ata. Cr. App. , 1978) i Htghtower v. State,, 410 So.2d 442 (AIa. Cr.

App. 1981); BehI v. State, 405 So.2d 5l- (AIa.Cr.App. L981).

Consequently, any issues raised in the Writ of Error Coram Nobis

should be supported by a showing of cause and actual preiudice.

This memorandum will set out to establish those issues which will

most 1lkely survive the cause of actual prejudice test.

-6-

to constitute the cri.me charged. See, In re Winship, 39 7 U. S . 358,

25 L.Edzd 368 (1970), more specifically the trial judge must be

careful when lnstructing on ciicumstantial evidence and inferences

not to d1lute the prosecutions burden of proving every element

of the crlme beyond a reasonable doubt. This onJ-y occurs where

the jury is instructed that from proof of one el-ement they may

lnf er or presume the exlstence of other elements. S€, 9.g. ,

(1965); cf .,

Unltrd Etatce v, 0FIr, 6I3 F.2d 233 (10eh Ctr, I979),

Illegal or fraudulent votlng, S17-23-1, Code of ALa. (1975),

turn on caBtlng a ba11ot. Illegal neans unIawfuL, contrary to

1aw. The essentlal elements of fraud are:

t. A false sEatement of fact;

known by Lhe defendant to be false at the

Sandserom v. Montana, 422 U.S. 5

States v. Romano, 382 U.S. 136,

5.

10, 6L L.Ed.2d 39 (1979); Unlted

L. Ed

2.

4,

tlme made;

to act lnmade for the purpose of inducting someone

reliance;

an actlon by someone ln rellance upon the correct-

ness of the representatlon; and

damage to one i-n reliance.

See, Vance v. Indian Hammock Hunt & Riding Club, Ltd., 403 So.2d

L367 (F1a. App. 1981) . Thus, there must exist lntent to deeieve

and the knowledge that onets actons are fraudulenE; and unlawful.

AlEhough fraud and perjury both involve willfully making a false

statement of fact, perjury requlred a falsely rc Btatement.

Thte requlrea an unequivocal act ln sone forr 1.e., a vaLld oath

or affirmatlon, ln the presence of an officer autho rLzed to

-2-

administer oaths. Goolsby v. Srate, L7 Ala. App. 545, 86 So

(1920). Thus, different facts are required to establtsh the

L37

commission of perjury under S13-15-115, code of Ala. (r975) than

are necessary for a findlng of fraud. rn addltion, the false

swearlng must have been done not only wi11ful1y but corruptly.

Thls suggests a greater degree of curpabil-ity to estabrtsh its

commlsslon than thaE whlch 1s needed for fraud. It is reasonable

to conclude that perJury under SL3-5-IL5 and lIlegal or fraudulent

votlng are separate and dlstinct offenses. Thls would preclude

the court from lnstructing on both unLess the defendants lrere

charged wlth both offenses. The lndlctment chargee the defendants

wlth vLolatlng $17-23-L. No reference to $13-5-115 1e made and

there 1s no statement of words alleged to have been falsely spoken,

whtch wouLd normaLLy be lncluded ln an tndtctment chargtng perJury,

Therl!orc, to the actuaL preJudlce of the defendante, the Court .

erroneously lnstructed the jury on an o,ffense not charged ln the

indictment. Thts has been held to violate the Flfth Amendment

guarantee that an accused shall only be held to answer for

crimes on an lndictment of a grand jury. See, United States v.

CarroLl, 582 T,2d 942 (5th Cir. L97B) (p1ain error found when

courtrs charge inc,luded an offense not charged in the lndictment).

I^lh11e consplracy Ls a dlstinct. statutory offense requlrlng

a corrupt agreement bet\^reen two or more persons, Code of A1a.

$13-9-20 (1975), there 1s a case law which suggests that con-

spiracy to do an act is a lesser included offence of the crime

actually committed. See, Smith v. State, B Ala. App. 187, 62

So. 575 (1913) , and acquittal of the crime does not constitute

scquLttal of the consplracy to commLt the crtme. See-, ConneIly

v. State, 30 Ala. App. 91,1 So.2d 605 (1941). Thus, where a

-3-

crime has been committed and there 1s sufficient evidence from

which the jury could reasonably infer there was a concerted

action t,o commit the crime, an instruction on conspiracy is

appropriat e.

rn addltion, Alabama case law does not requlre that one be

charged wlth conspiraey under a sectlon of the code to be con-

victed for conspiracy. see, Jo11y v. state, 94 AIa. 19, 10 so. 606

( ). Defendant ln that case \.ras indlcted and convlcted for

assault with intent to murder, yet the evldence dld not tend to

show that he actually committed the assauLt. The Court held thaE

SL4, Tltle L4, code of A1a. (L94o), aboLlshes rhe dlsrlncrlon

between accessory before the fact and princlpaLs, and authorLzed

conviction of one charged in indictment wlth havlng been actual

perpetrator of the crlme on proof of consplraty. .IlL. Thls may

be heLd to vlolate the r'lfth Amendment requlrement of notlce to'

the accused if the indictment does n,ot state that the defendant

was f ound to be aetlng j.n concert, wlth ot,her parties. united

States v.-carro1l, supra, p. 1. consequently, if a jury berieve

beyond a reasonable doubt that there was community of purpose,

each person is guilty of the offense committed whether he did any

overt act or not. s-to.kley-, SJ!E, at 29l, Note, however, that if

an offense is committed by one or more of the perpetrators from

causes having no connection with the common obj ect,, the responsibility

for such offense fa11s exclusively on the actual perpetrator. Id.,

at 293.

In Bozemanrs caser reference to the 1aw on conspiracy in the

instructions to the jury was not lmproper where sufficient evidence

-4-

was presented for the jury Eo infer concert of actlon. From

this the jury was allowed to flnd Bozeman guilty of illegal

voting wlthout proof of the element,s of that crime.

/ttre general rule in ALabama for reviewing a trial courtIs

jury charge is to conslder the charge as a who1e, ln its

total-lty, wlthout lsolating staEements, whlch indlviduaJ-1y

nay appear prejudlcial from the context ln whlch they were

rnade. Johnson v. State, 399 So.2d 859 (AIa. Cr. App. L979),

judgment afftd in part, rev'd in part, AIa. 399 So. 2d 873,

on remand, AIa. Cr.App. , 399 So.2d 875, appeaL after remand, ALa.

Cr.App. , 399 So.2d 875. If the lnstructl-on t'as a whole" could

have prevented the jury from understandlng the crlme wlth;which

the defendant was charged then lt wtll be found to have affected

the substantlal rlghts of the accused. Jqhnson v. SEate, .upr".7

The consplracy charge ln Bozeman's case was wlthln the reaLm

of judiclal discret,lon assuming ther! Was sufficient evidence

from whtch Lhe jury could reasonably l-nfer eommunlty of PurPose

between Bozeman .and Wilder. WhiIe it is true that the concerted

actj.on need not be proved by direct evidence, mere Presence at or

near the scene of the crime, without more, is not sufficient to

nake the accused a party to Ehe crime. Kendrick v. StaEe, supra

at 1112. Bozemant s presence says nothl-ng about her role l-n the

alleged conspiracyr f,or does it allow a legltimate, reasonable

inference that she had knowledge of a scheme to voEe iI1egaLIy.

Therefore, if j-nstructions on conspiracy are to be challenged we

must, show the evidence was insufficient for a jury to reasonably

infer an agreement between Bozeman and EI]4!g for the PurPose of

t1lcgal1y and fraudulently castlng baLlots.

-5-

Part III

Was the verdict against the weight of the admissible sub-

stantive evidence given:

A. The prosecution's reliance on prior inconsistent

statements;

B. The court's failure to instruct the jury on the

limited admissibility of prior inconsistent

statements thus allowing the jury to consider

the evidence as substantive; and

C. The circumstantial evidence presented with little

or no dj-rect evidence from which a jury could

reasonably infer guiltr or agreement, beyond

a reasonable doubt.

At the close of the Staters case, a motlon was made by the

defense to exclude state's evidence on.the grounds that it did

notsufficiently connect Bozeman with the alleged i11ega1 act.

The motion was denied and the case was submitted to the jury.

On direct appeal from the lower court's decision counsel

asserted the evidence was insufficient to sustain the conviction

for the following reasons: (1) where blacks vote in any sub-

stantia] numbers, a number of ballots would be cast for the

same candidate so there is nothing unusua] about that occurrence

in this case; (21 it is not unJawful for one person to pick up

more than one absentee ballot application; (3) it is not

unlawful for one person to assist more than one person in

fi]ling out an absentee application i (4) it is not unlawfu]

for person assisting an absentee applicant to put his own return

address on the absentee application; (5) the failure of the person

to sign the ballot in the presence of a notary public does not

render that ballot itself i11egal or fraudulent; (6) it is not

unlawful to return more than one absentee ballot to the office

of the Circuit Clerk; and (7) it is not clear that Bozeman

returned the ballots t,o the Clerk's of fice. The Alabama Court

of Criminal Appeals rejected this argument stating that the test

applied to determine the sufficiency of the evidence is whether

the jury might reasonably find that the evidence excluded every

reasonable hypothesis except that of guilt. Dolvin- v. State,

391 So.2d 133 (AIa. 1980) The question of the sufficiency of

the evidence should be reexamined on the grounds that:

(1) Prior inconsistent statements were improperly

admitted as substantive evidence resulting in

cause and actual prejudlce, and

without these statements there was not suf-

ficient uncontradicted evidence to exclude a

reasonable hypothesis of the defendant's

innocence.

l2)

A. The Prosecution Used The Rule Allowing A Party

To Impeach His Own Witness To Get Otherwise

Inadmissible Evidence Before ,1. Jury.

The Federal RuLes of Evidence, 801(d) (7) (A) , 28 U.S.C.A.

authorize the use of prior inconsistent statements as substantive

evidence subject to certain limitations. The statement must

have been made under oath at a trial, hearing or other proceeding,

of in a deposition. The rule also required that the declarant

2-

testify at the trial and be subject to cross-examination.

Although the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals follows the federal

rule and allows prior inconsistent statements to be used sub-

stantively, see, Whitehurst v. Wright, 592 F.2d 834 (5th Cir.

19791; United States v. Palacios, 556 F.2d 1359 (5th Cir. L977),

the settled rule in Alabama has been that the

Self contradictory statement of a witness who

is not a party, is not substantive evidence

of the facts asserted; and the statement

operated only to discredit the witness and

cannot be made the basis of a finding of

fact necessary to the establishment of

liability or defense

Randolph v. State, 348 So.2d B5B (Ala. Cr. App. L977\ | cert.

denied, Ex Parte Sta}e Ex Rel Atty. Gen., 348 So.2d 867 (Ala.

1977l'i McElroy, Law of Evidence in Alabama, S1.59.02 (1) , (2d.ed) .

Note that if the witness admits the truth of the prior statement

(versus denying them or admitting to having made them but

denying it,s truth) tne witness in effect adopts the prior st,ate-

ment as present testimony, eliminating the hearsay problem.

Feutralle v. U.S. 209 F.2d 159 (5th Cir. 1954). Even though

prior inconsj-stent statements are generally inadmissible as hear-

sdy, they are admissible for the limited purpose of impeachment.

Alabama adopted this rule as early as 1BBB and the courts have

consistently upheld this view. See, Jones v-. Pe,Jham, 84 AIa.

208, 4 So. 22 (1888). Such statements may also be used to

refresh recol-lection. See, Hudson v. State, 267 So.2d 494 (A1a.

Cr. App. 1972).

Impeachment testimony is admissible only when a party is

genuincely surprised. At the witness testinnony and the party's

cause is disadvantaged by the unexpected response. See,

3-

Dennard v. State, 405 So.2d 408 (Ala. Cr. App. 1981); cf. Federal

Rules of Evidence, rule 607, 28 U.S.C.A. (can impeach own witness

without a showing of surprise) . The Al.abama courts' rigorous

adherence to the surprise standard before admitting prior

inconsistent statements for impeachment is to prevent impeach-

ment from becoming nothing more than a device to get into evidence

before the jury that which would otherwise be inadmissible. Cloud

v..-_Il.oo,n, 290 Ala. 33, 213 So.2d 196 (1973). In Young Y. IJ.nLtgd

States, 97 F.2d 200 (5tfr Cir. 1938) a conviction on murder was

reversed because the District Attorney offered in evidence state-

ments allegedly made by the defendant to three fellow inmates

without showing surprise. The statements did not conform to the

Texas Code of Criminal Procedure requiring a written form and

warning, y€t the entire testimony of one key inmate was admitted

over defense counseJrs objections. The prosecutor lnew t,he key

witness was going to deny his previous rendition of the facts

but still stated the evidence was offered for impeachment. The

Court held

. it is equally fundamental that the

impeachment testimony be admitted not for

the purpose of suppJying what the witness was

.expected but did not say [I ] n no

event may the fact that a witness has made

contradictory statements be used as it in

effect was here, as a basis for completely

discarding the rul.es of evidence against

hearsay and Ex parte statements, and, as

impeachment, opening the flood gates of

prejudicial anC damaging hearsay. Id., at

205, 206.

This has been the uniform rul.e in the Fifth Circuit.

Mr.ississippi v. Durham , 444 !-.2d 152 (5th Cir. 197I) ;

v. Mi1ler, 664 F.2d 94, (5th Cir. l9BI).

See,

United States

A_

Thestandardappliedbythecourtstodetermineifimpeach-

ment testimony has been abused is vrhether the testimony goes

beyorrdthepurposeforwhichitisa.dmissible.UnitedStatesv.

Dobbs,44BF.2d1262(5thCir.1971).Impeachmenttestimonymay

beadmittedonlyinsofaraSitservedtoremovethedamagewhich

theSurprisehascausedandcannotbeusedtosupplytheantici-

pated testimony. Uniteo States v' .Gregory ' 412 F'2c1 484 at 481

(5th Cir. 1973). In Gregory the Court of Appeals found reversible

error where the government in the guise of impeachment brought in

affirmativeevidenceongroundsofSurprise,wheresuchevidence

washigh}yprejudicia}andvlasnottestifiedtobyanyother

witness at, trj.aJ, where the accuracy of the transcript was ques.

tionable, and where the court failed to instruct the jury that the

evidencecouldonlybetakenasevidenceofcrec]ibility.The

statementsintroduced,supplementedthevlitness,s'accountof

eventswithoutSpecificallycontradictinganythingsaidinhis

trial testimony' Thus goi-ng beyond the point of surprise' Even

where the staternents did contradict the witness' trial testimony'

t,he manner in which the government had alIegedly been surprised

was not established. All these circumstances prejudiced the

trialproceedings.Toavoidtheprejudicia]effectsofadmitting

priorinconsistentstatementsthecourtsuggesteda}lowingthe

Surprisedpartytowithdrawthewitnessancstrikehistestimony

fromtherecord.Ld.,dt4BB,se.e,alsOrunitedstatesv'Dobbs'

supra; Young -v. Unite$ States ' supra '

Whereaprlorinconsist,entstat,emontisusedwithinthe

narrow limits of removing surprise but is the onty evidence in

supportofSomeessentia]fact,itdoesnotprovidesubstantia]

c

factual basis as to each element of crime sufficient to provide

support for conclusion of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt' See'

Eisenbers v. U.S. , 273 F.2d 127 (5th Cir' ) ; United Stateq v.

oppico, 599 F.2d 11.3 (6th cir. ]979). A limiting instruction on

the effect of the impeaching statement would not be appropriate

,,. since the insufficiency of the evidence would not justify

the case being submitted to the jury. ." IsLe]l.v. State,57 Ala'

App.444,32gSo.2d133(t976),Cert.denied,295A}a. , 329

So.2d 140 ( ). In IsbqLI, the appellant was merely

present in the automobile, owned and operated by another person'

in which the stolen guns were found. The prosecution read a co-

perpetrators prior statement for the alleged purpose of refreshing

recollection. The court, held tht uncorroborated t,estimony could

not support a convlction and defense counselts motion to exclude

state's evidence should have been granted. Id., dt 140.

prior inconsigtent statements are of,ten admitted into evidence

when a witness is declared hostile. A wltness partially or totally

unfavorably answering questions propounded by a party calling him

does not immediately create an adverse situation requisite for

that party to cross-examine.* Nor is hostility created by a

witness' failure to testify to the Same statement previously

made. wiggins v. stale, 398 So.2d 7BO (A1a. Cr. App. 1981),

writ denied, A1a., 398 So.2d 783' The party

calling the witness must be Put to a disadvantage by the witness

response. Oennggg v. State, 4045 So.2d 408 (AIa. Cr' App' 1981) '

The final decision

judge's discretion.

to call a witness hostile is within the

6-

When a witness claims he does not remember a certain

fact in issue the party calling the witness may, by way of

surprise, question the witness eoncerning his prior inconsistent

statement for purposes of refreshing the witness' recollection.

Fed. R. Evid., 612. Thus, where mere failure of the witness

to remember is not sufficlently harmful to justify impeachment,

it established a foundation for refreshing recollection. The

cardinal rule is that unless the statement may be introduced

under the hearsay rule (I.e., 801(d) (1)) or one of its excep-

tions, (1.e., 803 (5) ) they are not, evidencer but only aids in

giving evidence. McCormick on Evidence, 59 (2nd Ed. 1972) i see,

Parsons v. State, 251 Ala. 467, 3B So.2d 209 (1948). Generally

t,he wit,ness Is handed the writing while on the witness stand

and t,he vlitnesB elther admlte or denl-es memory belng refreshed.

If the witness'memory is refreshed, the witness may refer to the

writing but is considered t,o be testifying from present memory.

If the witnessr recollection is not refreshed, it is improper

for counsel to read the writing aloudr urrless the writing is

admissi-ble as past recollection recorded. Ped. R. Evid. 803(5).

To be admissible as such the memo must have been prepared or

adopted by the witness and the witness must admit that the

matters stated therein are the truth. See, Freeland v. Peltier,

44 S.W.2d 404 (Tex. Civ. App. 193]) ; Fed. R. Evid. 803 (5) .

The memorandum may then be read j.nto evidence. McCorrnick, E!!8,

S299. The riEht of opposing counsel to examine the material

ttsed by a witness whil-e on the stand is not an unbridled right,

but is subject to reasonable l.imitations. Johnson v. State,

7-

398 So.2d 393 (Ala. Cr. App. 19Bl). For example, if the damaging

testimony of the witness was based upon repeated reference to a

memo that was not shown to defendant for the purpose of refreshing

memory, the substantial rights of the accused were affected.

Montgome.ry v. United St.ates, 203 F.2d 887 (5tfr Cir. 1953) where

the government proved the elements of each offense without the

use of witness statements the defendant did not suffer prejudice

due to absence of a limit,ing instruction. See, U_!1..!9d States v.

Slsto, 534 P12d 61.6 (5th Cir. 1976).

The transcript,s of the Wilder and Bozeman trials reveal

substantial disregard for the rules of evidence followed in

Alabama case law and the Federal rules of evidence. Assuming the

prior statements are not considered as substantive evidence. In

the Wilder trial incriminating testinnny against the defendant was

repeatedly admitted under the guise of refreshing recollection

or impeachment. When the prosecutor was not allowed to impeach

Rolllns with a statementhe gave at the Distrlct Attorney's office,

he asserted the witness needed to hhve his memory refreshed and

was allowed to proceed. Rollins did not admit to Wilder's

presence in his office on the date the ballots were notarized

until after reading his prior statement. In effect the prosecutor

was allowed to use the prior statement to supply the testimony

needed to incriminate Wilder. Note that no other witness at trial

testified on this matter. Defense counsel requested examination

of the deposition used to refresh and this request was ignored.

(Defense counsel did not pursue this request) . This testimony

was extremely damaging and failure to allow defense counsel to

examj-ne the deposition affected the substantial rights of the

8-

accused to adequate).y cross-examine. See, Mr.ontg-om.ery, strpra.

On direct examination of Robert Goines the prosecution

used leading questions without having the witness declared

hostile so that Goines denied knowing anything about absentee

voting. This is contrary to the rule limiting the use of leading

questions to cross-examination. Fed. R. Evid. 611.

During the examination of Bessie Billups the prosecuting

attorney refreshed ler memory with a deposition wherein she

stated she had never seen an application or baIlot. This was

done after Billups testified that, she made the marks on the

ballot exhibited. Again, the prosecutor used prior inconsistent

statements to elicit the testimony he wanted.

Further abuse by the prosecutor occurred during the direct

examination of Fronnie Rice. (p. 1650 At first Rice testified

that she got an application for a ballot from Wilder, signed it

and also signed the ballot herself with Julia Wilder acknowJedging

her mark. At thls point the district attorney declared her a

hostile witness and used the deposition to impeach Rice. The

deposition stated thaL Rice only signed an application and never

received a ba11ot.

In addition, the prosecutor made reference to Rotlins deposi-

tion testimony which stated that one of the ballots brought to

him was improperly signed. (pg. 300) Mentioning this in the

closing argument could lead a jury to believe it was to be con-

sidered as substantive evidence.

During the Bozeman trial the prosecutor used the deposition

testimony excessively, in addition to leading questions on

direct examination. The prosecutor repeatedly asked Rollins

9-

if Bozeman made the phone cal.1 to set a date for notarizing

ballots. Rollins testified that he could not say for sure that

it was Bozeman even though she was present when the ballots were

notarized. Rollins is given the deposition to ',refresh" his

memory on question of whether Bozeman ca11ed. After examining

the transcript Rollins has no present recollection of the events

testified to therein. At this point the prosecutor asks for

permission t,o cross-€Xarninethb wit,ness as a hostile wltness.

The court did not allow this but on redirect the prosecutor read

the deposition. This was clearly an attempt by the prosecutor

to get the prior statements in evidence, which he could not do

otherwise because:

(1) Rollins testimony was

the statement could be

if it were admissible

recorded;

(2) the court wouLd not a1

impeach the witness.

not refreshed therefore

read into evidence only

as past recol.l.ection

a:

1ow the prosecutor to

Fronnie Rice was declared a hostile witness because she did

not respond to the question whether she signed the application and

ballot alone in the manner desired by the district attorney. The

deposition testimony stated that Rice signed the application but

never got the ba1lot. The prosecutor properly read the deposi-

tion after Rice admitted she gave the statement. This testimony,

however, was admissible solely for the purpose of impeachment.

Lou Sommervill-e was also declared a hostile witness because

she testified at trial that she did not go to Bozeman's house

10

for an application. The deposition states that she went to

Bozemanrs house for the application and Bozeman signed her

(sommerville's) name. rt also states that she did not get a

ballot in the mail. The witness was declared hostile and the

prosecution read theentire deposition into evidence. Generally

the state is allowed to question the witness concerning the

prior statement and elicit the portions contrary to his instant

testimony accordingly. D-e_nnard v. state , 405 so.2d 4og (Al.a.

Cr.App.1981).Thisu.mprosecutionCanreadthe

enti.re statement without eltciting reEponseE from the witness,

Thus, the district attorney improperly read the deposition

testimony of Lou Sommerville because he did not wait for her to

respond to each question and answer recited.

It is important to note that Sommerville admitted to giving

a statement at the district attorneyrs office but she denied the

truth of the matters asserted therei4, She stated that she was

telllng t,he truth at the t,rial. Reading the entire deposition

goes beyond the purpose for which it was admitted because it

not only states that she went to Bozemanrs house for an applica-

tion but that.she never received a ball.ot in the mail and voted

at the armory

The prosecution has used the failing memory of these aging

wi-tnesses to admit evidence under the guise of refreshing

recollection sin6e all the prosecution needs to show is that the

witness can not remember the events in question. This is a

more rel.axed standard than a showing of surprise which is re-

quired prior to the admission of impeachment testimony.

1l

The preceding discussion on the trial transcript assumes

that the statements could not be admitted as substantive

evj-dence. Under the Federal Rules of Evidence prior incon-

sistent statements taken under oath, subject to the penalty of

perjury are admissible as substantive evidence. Fed. R. Evid.

801(d) (1). If the statement taken under oath was a deposition,

the Federal rules of Criminal Procedure, 1.5, impose further

restrictions. This is to protect the defendant's right to con-

frontation under the Sixth Amendment. The defendant must receive

a reasonabJe notice of the time and place the deposition wilI be

taken. The Code of AJabama S12-21-261 requires that the defendant

file his written consent for the taking of any witness' testimony.

In our case there is nothing in the record to show defense

coungel wag notifled t,hat Eworn Etetements were being taken or

that any consent was given. If the depositions were improperly

obtalned they.coul.d not be considered a deposltlon within the

meaning of Code of Al.a. 512-21-261 or Fed. R. Crim. Pro. 15 and

therefore would be inadmissible as substantive evidence. A question

can be rasied as to whether the depositions were an accurate record

of what the witness said because on VOIR DIRE Lou Sommervil.le

(pg. 168 Bozeman transcript) testified that there was no one

taking down her statements and onJ-y she and Pep Johnson were

present. Even if the statements were adequate to establish

admissibility (e.9., where taken under oath when the events were

fresh in the witness' mind) when such evidence is the only source

of support for the central alLegations of the charge it usually

is not considered sufficient for a conclusion of guilt beyond a

l2

reasonable doubt. See, United States v. Orrico, supra; United

States v. Boulahanis, 677 F.2d 586 (7th Cir. I9B2).

l3

B. The CourE's failure to give a limiting instruction sua

sponte of the impeachment testimony affected the substan-

tial rights of the defendants.

Assuming a prior inconsistent statement is admissible for

lmpeachment purposes, it must not be used as the basis for

establishing guilt of the accused. It 1s true that the iury should

judge the weight and sufficiency of ther evidence, but onl-y sub-

stantlve evidence should weigh on the question of guilt or

innocence. The question arises whether the judge has a duEy to

glve a llmltlng tnEtructlon, Bua Eponte.

The Bederal Rules of Evidence state that when evldence

admLsElbLe aE to one perty or for one purPose but not adrnisslble

as to another party or for another purpose is admitted, the Court,

upon request, shall- restrlct, the evidence to lts proPer scope

and tnettruct the Jury accordtngly. Fed, R. Evtd. 105. PIaln

error can be found on appeal where fallure to request a l-lmitlng,.

instructlon would preclude appellate review. Plaln error occurs

whcn the tmpeaehlng tsetlmony Le oxtremeLy damagtng, thB need for

the lnetructLon 1s obvlous, and the fallure to glve 1t 1s so

prejudiclal as Eo affect the substantial rights of Ehe accused.

Unj.ted States v. Sisto, 534 F. 2d 6]-6 (5th Cir. L976) .

The Fifth Circuit adhered to the practice of instructi-ng juries

as to the limited purposes for which impeachment evidence is

admitted, Sla!e,-v._--U-:J-:-, 267 T.2d 834 (5th Cir. 1959), but has

not held that failure to give an lnstructlon sua sponte auto-

matlcall-y resul-ts Ln reverslbl-e error. See, Val-entlne v. UnLted,

272 F.2d 777, 778 (5th Cir. 1959); United States v. Garcia, 530

F.2d 650 (5th Cir. L976), In Garcia the Court declined tb. find

find error where an instruction was not requested or given sua

- r4-

spont'e. The Court noted that the government had strong evidence

against the defendant before the prior inconsistent statement

r{as admltted, Eherefore, the lack of an instruction was not so

critical as to affect the substantial rlghts of the defendant,.

Id., at 656. Conversel-y, where the testimony brought out during

impeachment establlshed 1n large measure the subst,antive elemenEs

of the crlme which the government was required to prove, failure

Eo make speclfic reference to the impeachment evidence in the

general charge constLtut"d*plaln error. Unlted States v. LLpscomb,

422 F,2d 26 (6ttr Clr. 1970). In another case holdtng plain

error for fallure to lnstruct on the llmtted admlselbl1lty of

impeachment testlmony, the record showed no evldence on which a

convlctlon(of one witness by another witness I testimony) eould

rest oth'er than the unsworn prior inconsistent statemenEs of

an a1-1eged accompllce. United States v. Sisto, supra, at 625, :

The court assumed that a properly instructed jury would llmlt

ttr conElderatlon of the lmpeachtng testtmony to the lEeue of

credlbll1ty. Notlce qras given to the prosecutLonts reference

to the impeaching testimony in his closing argument whlch was not

considered in evidence.

*

The Court of Appeal-s went a step further ln United States

v. Gregory, 472 T.2d 484 (5th Cir. L973), advaneing the position

that the distinction between stat,ements used t,o destroy credibility

and those used to establtsh afflrmative factB "should be delln-

eated sharply in terms readily understandable by Lhe. jury."

Id. at 489. It r^ras not enough that the trial court said, "f or

irnpeaehment purposes only.tt Because that does not explain or

forbid its further use to establish the critical facts aE issue.

-15-

Id. at 489; see Randolph v. State, glftE at 860.

The Al-abama Court of Criminal Appeals has foll-owed the

f'ederal rule that the opponent of the evldence must request the

limltlng lnstructlon, otherwise, he may be heLd to have walved

it as unnecessary for his protection. Robinson v. State, 361

So.2d 378, writ denled 361 So.2d 383 (Ala. Cr. App. L978); see

Bythewood v. Stete, 373 So.2d LI70' wr!t denLed 373 So.2d LL75

(Ala. Cr. App, L979); Fed. R. Evld. 105. If the oPponent of

the evldence obJecte but doee not request an lnstructlon, the

overrullng of such an obJectlon glves hlm no ground for con-

p1alnt on appeal. Code of ALa. $12-16-13 (f g75) i eee Roblnson,

supra at 381.

Glven the Flfth Circuitrs favorable rullnge on the deslra-

bttlty'of lnetructlng Jurlee as to EhE Llmited admlaslblltty

of impeachment testlmony when: 1) Ehe lmpeachlng testl-mony

ls extremely damaglng; 2) the party uslng the testlmony has

a weak caBe wlthout the statement; 3) the need for the lnetructlon

ls obvlous; and 4) fail-ure to glve 1t ts so preJudiclal as to

affect the substantial rights of the accused, we should argue

that the Erial courtrs failure to give a limlting lnstruction,

sua sponter w3s error. A strong argument exlsts for Bozeman where:

1) the prosecution read Rollinsr deposltion testimony wherein he,

stated that Bozeman called him thus connectlng her with the

notarlzatlon scheme; and 2) the deposltlons used when examlnlng

Fronnle Rick and Lou Sommerville to shw they never got a ballot

in the mail contalned circumstantial evidence from which a jury

ay have reasonably inferred a scheme or plan. Without the

admission of this circumstantial evidence the SEate has onl-y one

-r6-

C. The cj-rcumstantial evidence while poss ibly creating

a suspicion of guilt dld not exclude to a moral

certainty every reasonable hypothesis but thaE of

the guilt of the accused

circumstantial evidence is the inference of a fact in issue

which follows as a natural .consequence aceording to reason and

common experience from known collateral facts. Dolvin v.

State, 391 So.2d 133 (1980) ; see, Lolrre v, State, 105 So. 829

(F1a. L925). An lnference is merely a permlsstble deduction from

the proven facts, Thomas v. StaEe, 363 So.2d 1020 (Ala. Cr. App.

1978), and "whiIe mere speculation conjecture or surmise w11I

n0t authorlze a eonvlctton the Jury ds under a duty to drew

whatever permisslble lnferences 1t may from cLrcumstanEial evidence."

Walker v. State, 355 So.2d 755, 758 (A1a. Cr. App. 1978); Thomas,

supra at 1022. Circumstantial evidence is ent,itled to the same

weifht as direct evidence provided it points to the guilt of

the accused. Hayes v. State, 395 So.2 d, 127 (A1a. Cr. App. fgBl)

The test applied by the Alabama courts for reviewing a coo-

vtetlon baeed on clrcumstantlal evtdence 1s "\nrhether the ctrcum-

stances as proved produced a moral convictlon to the exclusion

875

of every reasonable doubt." Cumbo v. State, 368 So.2d BTLl (A1a.

Cr. App. 1978) cert. denied, 368 So.2d 877 (A1a. I97B). The

evidence must be viewed in the light most favorable to the

prosecution, id at 137, and "the State I s evidence should not be

stricken out, as insufficient to supporE a convicEion, merely

because, when dlsconnected 1E ls weak and tnconcLus{ve, 1f, when

combined it may by sufficient to satisfy the guilt of an accused."

Hayes, supra at.J-47. Thus, in Hayes where there were no eyewitnesses

to the deceased leaving a bar with the defendant, and Ehe testimony

-18-

of each witness could only be used Eo draw inferences' the

Court refused to reverse for insufficient evldence. (An earring

connected to Ehe deceased was found in defendantfs car). Con-

versely, a defendant shouLd not be convicted on mere suspicion

or that the might have conmltt,ed the crlme. Jordan v-:- J!ate,

L57 So. 485 (Ata. 1934) . In Jor4.en, the def endant was convicted

of s econd degree murder where there \,sas no motlve shownr flo

hostllity, and empty pistol shel-Ls \.rere near the body but the plstol

wae, mlaelng. The Cour! reaBoned that whl1e 1t 1E not neceBs4ry

to explain all those circumstances, they or some of the evldence

must Ehow thc defendantre gutlty Parttctpatlon. Ig. 8t 486.

Circumstantial evldence alone was sufficLent to prove Par-

ticlpatlon in a crlme ln DoLvin, .gJ!E., but the circumstances

f ormeid a complete chaln polnt lng t,o the gullt by the daf endant .

The def endant I s proxlmity Eo the place of the crime aE 4 vex],'

rea6onable hour wlth the oPPortuntty to commlt the crlme was a

ctrcun.tanct to be wetghed by the J ury. Id. aE 67 3i 89.9, @!.'

supra at 830 (a11 the clrcumstances from whtch gulJ.t may be

lnferred was proved by direct testimony of eyewitnesses).

When the circumsEantial- evidence could resul-t in a finding

of guilt or innocence the Court will- ask whether a.jury might

xeasonably conclude Ehe evidence excludes every hypothesis

except that of gui1t. Dolvln, supra at L37 (emphasis added).

Thte ltne of reasonlng was f ollowed ln W-a,LESr v,-State-, 355 So ' 2d

755 (ALa. Cr. App.1978), and agaLn ln Cumbo v. State,368 So.2d

871 (Al-a. Cr. App. L979), In both cases the Court af f lrmed the

convlctions on grounds that even though Ehe evidence IiTas minimally

-19-

suf f l'clent, the \relght and suf f iclency of the witness t s

testimony \,vas.for the jury to declde.

The mere presence of a person at the time and place of a

crlme ls not sufficlent to justify an inference that the

accused committed the crime. See, Lol-1ar v. State, 398 So.2d

400, 402 (A1a. Cr. App.19Bl); Thomas v. State, supra; Kimmons

v. State, 343 So.2d 542 (ALa. Cr. App. 1977); Chatom v. State,

348 So.2d 828 (Ala. Cr.App,1976); Smlth v. State,326 So.2d 680

*A1e . App. 1976)t cert denLed, 295 Ala

686 (1976). Proof that the defendant was present in automobile

whlch was entered by two robbers created a susplclon of gulJ.t,

but was Lnsufficlent 1n ltself to support a conviction of robbery

Thomas, supra at L023. No money or weapons were found on Thomas

and it'was undlsputed that hb did not partLcipate ln the actual

robbery. There was no evidence which wouLd support an inference.

that Thomas was present wiEh the robbers near the scene of the

robbory before the commlsalon of the crtme or that he hdd any

knowLedge that a robbery was golng to be commLtted. Id. at

L023. Sueh facts as hls presence in connection with his compan-

ionship, his conduct at, before, and after the commission of the

act, are potent circumstances from whieh pa rticipation may be

inf erred, Id. at L023, and t,hes e f acts were not presented by

the State.

A contrary reeult wae reached ln $!|!, !-!l!l3, where the

facts surroundLng the alleged robbery dlstlnguish this case

from Thomas. The defendant was present ln the car when the

actual crime was committed. Although the defendant did not do

anything to incite the robbery, the Court concluded other facts,

r , 326 So,2d

-20-

such as his comPanionshiP with

conduct at the time (ttre moneY

would suPPort an inference that

commission of the offense. Sml Eh, supra at 685. Note, howevert

Ehar ln unlred sEaEes v. PaLaclos, 556 !.2d L359 (5th cir'

neither mere presence nor a close relationshlp between t'wo alleged

co-consllrators supPort'ed a consptracy charge'

Although the court ln Ktmmons, !-!l!13., wa8 concerned prlmartly

wlth the sufficlency of an accomPllcets uncorroborated testlmony

upon whtch the defendantrs convictlon rested, Ehe princlpals

stated thereln have ben applled to cases not lnvolvlng accomPllce

testimony. See, ]@, supra at, L37 , The court hetd that llthe

fact defendant and the accompllce were toget,her ln or near the

place where Ehe crlne wa8 qommLtted, $!.L, t.n conJ uu0tlon wtth othel

facts and ctrcunstancsEr eUfftc,tentLy tend to conntct the accuaed

wlth the commisslon of the crlme Eo furnlsh the necessary corrob-

orat,lon of the accompllce. " Klmmons, ji-glllg at 547

Where the cj-rcumstantial azidence may support an inference of

partlclpation in a crime it may also be used to infer a conspiracy

orcommunltyofPurpose.Again,otherfactsandcircumstances

are necessary to corroboraLe the mere presence of the accused aE

or near the scene of the crime'

ThecircumstantialevidenceagainstWilderisaSfol].ows:

l-) some ballot applicaLions were marked with an x but all t'he ballots

weresigned;2)\'rlilderpickedupsomeball-otaPPlicationsand

returned some buE no evidence Ehat the baIloE appl-ications ret'urned

by \^I11der gotrresPond to the apPlications exhiblted at triaJ.;

the actual PerPeEritors and his

was handed to hirn by co-def endant),

the defendant aided ln the

-2L-

.a

3) \dllderrs address was on some of the applications; 4) Witnesses

testimony that Wilder brought, them an application to sign, but

they never received a bal1ot; 5) 0ne of the ballots brought

to Rol-1lns was improperly signed; and 6) Sophia Spannrs Eestimony

that she dld not slgn the baLlot which was voted for her absentee.

Thls evieence when combined with the evidence Ehat l,trlLder handed

RoLllns the ballots and stated thaE the signat,ures were genulne

form a complete chaln polntlng to Wllderfs efforts to get bLacks

to vots abgcntee. UnleEB the events whtch occurred ln Rolllnre

offtce con6tltute r'111egal and fraudulent votlng," the chatn of

cvcnts are not lrreconctlable wlth any rGasonable theory of

WilderIs lnnocence with respct to Ehe crLme charged.

The clrcumstantLal evidence against Bozeman 1s as foLlows:

1) Bozeman plcked up abeentee balLot appllcatLone before the

electlon, but no evldence that she returned applicatlons herseJ-f;

(2) she was Ieen by Ms, T11ley tn Mrs, WtLderII car qrhen Wtlder

tl

r.turnGd sorre appltcatlons. (Thls evldBnce waE struck bccauae

obtalned by lurproper J-eadlng questton); 3) Bozeman was present

wlth Wl1der when the ballots were noEar rzed,; 4) Lou Sommervillers

deposition Eestimony which she never acknowledged at trial

statlng that she went to Bozemanrs house for an absentee appllca-

tion and she never received a ballot in the mail and 5) Sophla

Spannts Eestimony that Bozeman came to her after she had voted

to see lf she had voted. Thls svtdence alone oreates onLy a

susplelon of gulJ"t because mere presence does not sufficlentJ-y

connect the accused with the commission of the crime. l,lhen com-

blned with Rollinst testimony that Bozeman cdlted him to set, a

date for notarLzLng the applications

-22-