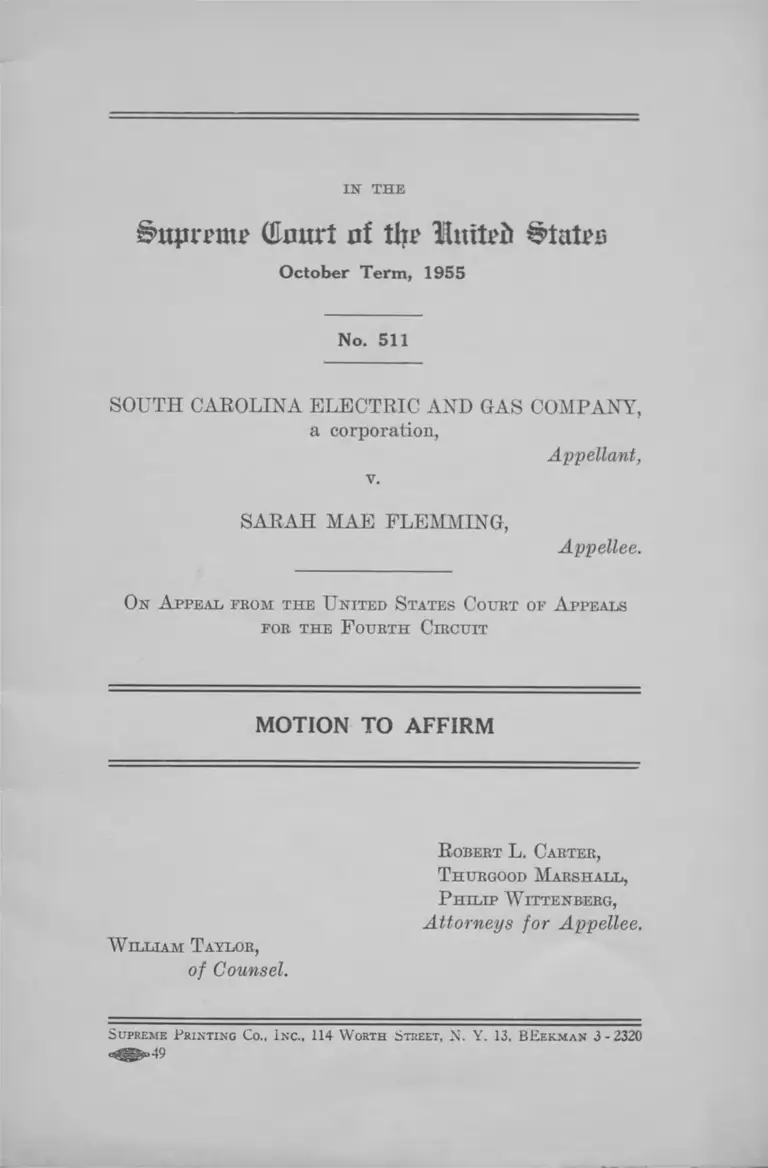

SC Electric and Gas Company v Flemming Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1955

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. SC Electric and Gas Company v Flemming Motion to Affirm, 1955. aa7a36e0-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8acd115b-13b6-45d1-af8c-a0bba15bedf8/sc-electric-and-gas-company-v-flemming-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

§>uju*ruu> (Eciurt nf tin' United States

October Term, 1955

No. 511

SOUTH CAROLINA ELECTRIC AND GAS COMPANY,

a corporation,

Appellant,

v.

SARAH MAE FLEMMING,

Appellee.

On A ppeal from the U nited S tates Court of A ppeals

for the F ourth Circuit

MOTION TO AFFIRM

W illiam Taylor,

of Counsel.

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

P hilip W ittenberg,

Attorneys for Appellee.

Supreme Printing Co.. I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13. BEekman 3-2320

<*̂ §£■>49

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement ..................................................................... 1

S ta tu te s ......................................................................... 4

Argument ...................................................................... 6

Table of Cases Cited

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ................................ 6, 7, 8

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ......... 6, 8

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ............................ 6, 8

Dawson v. Mayor, 220 F. 2d 386 (CA 4th 1955)........ 8

Dawson v. Mayor, — U. S. — ..................................... 6

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 ......... 7, 9,10,11

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, — U. S. — ..................... 6

Keyes v. Carolina Coach Co., — I. C. C. — ............. 7

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 8 8 ...................... 9

Moore v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 98 F. Supp. 375

(E. D. Pa. 1951) ........................................................... 12

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 374 ............................ 7, 8

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., —

I. C. C. — .............................................................. 7

Picking v. Penn. R. R. Co., 151 F. 2d 240 (CA 3rd

1945) .............................................................................. 12

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 .............................. 4, 6, 9

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................................ 6, 9

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ................................ 9

11

Statutes Cited

PAGE

S. C. Code, § 58-1402 (1952) ....................................... 4,11

S. C. Code, § 58-1403 (1952) ....................................... 5,11

S. C. Code, § 58-1406 (1952) ....................................... 5,11

S. C. Code, § 58-1422 (1952) ....................................... 5,11

S. C. Code, § 58-1461 (1952) ....................................... 6,11

S. C. Code, §58-1491 (1952) ...................................... 2,11

S. C. Code, §58-1492 (1952) ..................................... 2, 11

S. C. Code, § 58-1493 (1952) ....................................... 2,11

S. C. Code, § 58-1494 (1952) ....................................... 2,11

S. C. Code, § 58-1495 (1952) ....................................... 2,11

S. C. Code, § 58-1496 (1952) ....................................... 2,11

Title 28, United States Code:

Section 1343(3) ................................................... 11

Title 42, United States Code:

Section 1981 ........................................................ 11

Section 1983 ........................................................ 11

Title 42, United States Code:

Section 3(1) .......................................................... 7,9

Section 316(d) ...................................................... 7

IN TH E

Supreme (Ernirt of % THinttb

October Term, 1955

No. 511

S outh Carolina E lectric and Gas Company,

a corporation,

Appellant,

v.

S arah Mae F lemming,

Appellee

On A ppeal from the U nited S tates Court of A ppeals

for the F ourth Circuit

-------------------------------o-------------------------------

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Pursuant to Rule 16 of the Revised Rules of the

Supreme Court of the United States, appellee moves that

the judgment and decree of the Court of Appeals be

affirmed on the ground that the questions raised in this

appeal are without substance in law or fact and that the

judgment of the court below is clearly correct and in

accord with the decisions of this Court.

Statement *

On June 22, 1954, appellee, an American citizen of

Negro origin, boarded a bus owned by appellant, a public

service carrier engaged in the business of passenger trans

portation within the City of Columbia, South Carolina, pur

suant to franchise or certificate of public convenience. The

2

bus, like others in appellant’s fleet, had an exit at the

front and rear, a long vertical seat on either side of the

aisle, followed by several rows of horizontal seats and a

long back seat at the rear extending across the entire width

of the bus.

Title 58, Sections 58-1491-58-1493, Code of Laws of South

Carolina, 1952, makes segregation of the races on motor

vehicle carriers mandatory. Under Section 58-1491 failure

by the carrier to enforce segregation in its vehicles con

stitutes a misdemeanor, rendering the carrier subject to

penalties up to $250 for each offense. Under Section 58-

1493 a bus driver may be charged with a misdemeanor for

failure to enforce segregation and fined up to $25 for each

offense. Section 58-1495 subjects passengers to fines not

in excess of $25 for violations of the state’s policy, and

Section 58-1496 empowers the bus driver to eject passen

gers from the bus who refuse to comply with the carrier’s

regulations designed to enforce racial segregation and pro

tects the driver and carrier from suit for damages result

ing from such ejection.

Section 58-1493 empowers the bus driver to change the

designation of space “ so as to increase or decrease the

amount of space or seats set apart for either race . . .

But no contiguous seats on the same bench shall be occu

pied by white and colored persons at the same time.”

Under Section 58-1494 a “ driver, operator or person in

charge of any such vehicle, in the employment of any com

pany operating it, while actively engaged in the operation

of such vehicle, shall be a special policeman and have all

the powers of a conservator of the peace in the enforce

ment of the provisions of this article and in the discharge

of his duty as such special policeman in the enforcement

of order upon such vehicle.”

To comply with these provisions appellant has adopted

and enforces a policy, custom, rule, regulation or practice

3

pursuant to which white persons are seated from the from

to rear of its buses and Negro passengers from rear to

front. This policy, custom, rule, regulation or practice,

adopted and enforced under color of state law, makes it

unlawful for a Negro to occupy a seat in appellant’s bus

in front of or beside a white person, and conversely it is

unlawful for any white person to occupy a seat in back of

or beside a Negro.

When appellee boarded the bus in question, white per

sons were sitting in the forward section of the bus. Pur

suant to appellant’s policy that section of the bus thereby

became the “ white” section, and all Negro passengers had

to take seats in back of those occupied by white persons.

All seats to the rear of those occupied by white persons

became the “ colored” section and were all occupied, and

many Negro passengers were standing when appellee

boarded the bus. Because of the crowded condition of the

bus, appellee stood in the forward or “ white” section of

the bus. Thereafter, a white passenger left the bus, and

appellee took the seat vacated which resulted in her sitting

in front of one or two white passengers, and the alterca

tion resulting in the instant lawsuit ensued.

The bus driver in a loud and threatening tone ordered

appellee to get up from the seat she had taken. She did

not obey at once, and he repeated his order. In fear of

further humiliation and possible bodily harm appellee left

the disputed seat and prepared to leave the bus by the

front exit, although as yet some distance from her desired

destination. The driver permitted white passengers to use

this exit but ordered appellee to leave by the rear door,

and he struck her to enforce his command.

Appellee, having suffered physical injury, humiliation

and embarrassment resulting from the state’s policy, com

menced the instant litigation, an action for damages, in

4

the district court on the ground that the South Carolina

statutes requiring racial segregation on intrastate motor

vehicle carriers are unconstitutional and void, and that

appellant’s enforcement of the state’s unconstitutional

policy violated appellee’s rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment. The district court held that Plessy v. Fer

guson, 163 U. S. 537, was controlling and granted appel

lant’s motion to dismiss on the merits. Its decision is

reported at 128 F. Supp. 469. The Court of Appeals re

versed on the ground that the state’s policy is unconstitu

tional in that the “ separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy

v. Ferguson was no longer a correct statement of the law

and could not be applied to intrastate commerce. It is

reported at 224 F. 2d 752. This appeal followed.

Statutes

Appellant in its jurisdictional statement has set forth

some of the statutory law which should be considered in

connection with this appeal. In addition to the statutes

cited by appellant the following statutes are evidence of

the control the state exercises over appellant’s operation,

and are, therefore, important to the disposition of this

appeal:

§ 58-1402. Transportation by motor vehicle for com

pensation regulated.

No corporation or person, their lessees, trustees

or receivers, shall operate any motor vehicle for the

transportation of persons or property for compen

sation on any improved public highway in this State

except in accordance with the provisions of this

chapter and any such operation shall be subject to

control, supervision and regulation by the Commis

sion in the manner provided by this chapter.

§ 58-1403. Certificate and payment of fee required.

No motor vehicle carrier shall hereafter operate

for the transportation of persons or property for

compensation on any improved public highway in

this State without first having obtained from the

Commission, under the provisions of article 2 of

this chapter, a certificate and paid the license fee

required by article 3.

§ 58-1406. Penalties.

Every officer, agent or employee of any corpora

tion and every other person who wilfully violates

or fails to comply with, or who procures, aids or

abets in the violation of, any provision of articles 1

to 6 of this chapter or who fails to obey, observe or

comply with any lawful order, decision, rule, regu

lation, direction, demand or requirement of the Com

mission or any part or provision thereof shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor and punishable by a fine

of not less than twenty-five dollars nor more than

one hundred dollars or imprisonment for not less

than ten days nor more than thirty days.

§ 58-1422. Revocation, etc., of certificates; appeal.

The Commission may, at any time, by its order,

duly entered, after a hearing had upon notice to the

holder of any certificate hereunder at which such

holder shall have had an opportunity to be heard

and at which time it shall be proved that such holder

has wilfully made any misrepresentation of a mate

rial fact in obtaining his certificate or wilfully vio

lated or refused to observe the laws of this State

touching motor vehicle carriers or any of the terms

of his certificate or of the Commission’s proper

orders, rules or regulations, suspend, revoke, alter

or amend any certificate issued under the provisions

6

of articles 1 to 6 of this chapter. But the holder of

such certificate shall have the right of appeal to

any court of competent jurisdiction.

§ 58-1461. Commission to supervise carriers; rates.

The Commission shall supervise and regulate

every motor carrier in this State and fix or approve

the rates, fares, charges, classification and rules and

regulations pertaining thereto of each such motor

carrier. The rates now obtaining for the respective

motor carriers shall remain in effect until such time

when, pursuant to complaint and proper hearing,

the Commission shall have determined that such

rates are unreasonable.

Argument

1. There can no longer be doubt that the “ separate but

equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, pursuant to which

states have enforced and maintained racial segregation

and discrimination in both public and private institutions,

is no longer a reliable yardstick to determine whether a

state has met its obligations under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States. It must be

conceded, of course, that this Court has not expressly

rejected the application of Plessy v. Ferguson to intra

state commerce. On the other hand, the “ separate but

equal” doctrine has been steadily restricted and expressly

repudiated in other areas, and these decisions indicate, we

submit, that the Plessy' decision is no longer controlling,

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Bolling v.

Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (public education); Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U. S. 60; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1

(housing); Dawson v. Mayor, — U. S. —, and Holmes v.

City of Atlanta, — U. S. —, decided November 7, 1955

(public recreational facilities and activities). Further,

7

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 374 (which invalidated the

application of state laws requiring segregation to inter

state commerce) and Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S.

816 (which states in effect, if not in terms, that enforcement

of the “ separate but equal” doctrine constitutes a for

bidden discrimination under the Interstate Commerce

Act)1 cast serious doubt on the doctrine’s validity in intra

state commerce.2 No valid reason exists, we submit, which

warrants maintenance of “ separate but equal” in intra

state commerce when it has been abandoned in other areas.

The truth of the matter is that the “ separate but equal”

doctrine has been riddled unto death. It is at war with

the Court’s present, interpretation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, and all its rationale has been rejected by

this Court. No longer will a mere showing that equal

facilities are made available to the Negro group suffice

to sustain a racial classification as was the case when the

Plessy doctrine was considered controlling. For this Court

has now taken the position that racial classifications are

suspect and must be subjected to the most careful scrutiny.

See Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, where the Court said at

pages 499, 500:

Classifications based solely upon race must be

scrutinized with particular care, since they are con

1 Title 49, United States Code, Section 3(1).

2 The doctrine was dealt another blow in National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry.

Co., — I. C. C. —, and Keyes v. Carolina Coach Co., — I. C. C. —,

decided November 7, 1955, by the Interstate Commerce Commission,

in which the Commission found that segregation in interstate railroad

coaches, buses and station waiting rooms constitutes an undue preju

dice and disadvantage in violation of the Interstate Commerce Act

(Title 49, United States Code, Section 3(1)) and the Motor Car

riers Act (Title 49, United States Code, Section 316(d)), even

though “separate but equal” facilities are provided for Negro passen

gers.

8

trary to our traditions and hence constitutionally

suspect. As long ago as 1896, this Court declared

the principle “ that the Constitution of the United

States, in its present form, forbids, so far as civil

and political rights are concerned, discrimination

by the General Government, or by the States, against

any citizen because of his race.” And in Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 . . . the Court held that a

statute which limited the right of a property owner

to convey his property to a person of another race

was, as an unreasonable discrimination, a denial of

due process of law.

Although the Court has not assumed to define

“ liberty” with any great precision, that term is

not confined to mere freedom from bodily restraint.

Liberty under law extends to the full range of con

duct which the individual is free to pursue, and it

cannot be restricted except for a proper govern

mental objective. . . .

Nor is the police power argument relied upon by the

Court in 1896 persuasive today. See Buchanan v. Warley,

supra; Morgan v. Virginia, supra. As the Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit said in Dawson v. Mayor,

supra, 220 F. 2d 386, 387, “ segregation cannot be justified

as a means to preserve the public peace merely because

the tangible facilities furnished to one race are equal to

those furnished the other.”

Moreover, the great body of legal authority cited to

support the decision reached in the Plessy case were lower

state and federal decisions upholding segregation in the

public schools. These authorities were repudiated in

Brown v. Board of Education, supra, and Bolling v. Sharpe,

supra.

9

The “ separate but equal” doctrine has been rejected

in all material respects. All that remains is the formality

of expressly overruling Plessy v. Ferguson in the field of

intrastate commerce, the only area where the “ separate

but equal” doctrine has been applied by this Court. We

respectfully urge the Court to take this opportunity to

overrule the Plessy case and thereby grant this trouble

some concept a final repose.

2. Henderson v. United States, supra, suggests that

racial segregation in transportation is a prohibited dis

crimination forbidden under Section 3(1) of the Interstate

Commerce Act. Undue prejudice and disadvantage pro

hibited under Section 3(1) of the Act has been given the

same meaning by this Court as the Fourteenth Amend

ment’s mandate of equal protection of the laws. For ex

ample, compare the statement in Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U. S. 629, 635, that rights under the Fourteenth Amend

ment are personal and present with that in Mitchell v.

United States, 313 U. S. 88, 97, concerning the personal

character of rights under Section 3(1) of the Interstate

Commerce Act; and compare the statement in Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22, that indiscriminate discrimina

tion is not equality under the Fourteenth Amendment with

a similar pronouncement in Henderson v. United States,

supra, at 825, concerning equality under the Interstate

Commerce Act.

In the Henderson case, the Court struck down a car

rier regulation pursuant to which a table for four persons

was permanently reserved in the carrier’s dining car for

the exclusive use of Negro passengers, while the remaining

tables were reserved exclusively for white persons. The

Court found the regulation invalid as it did not prevent

the possibility that a Negro might be denied service where

the table reserved for Negroes was in use, but there were

vacancies in the other part of the dining car. The Court

said on this point at pages 824, 825:

10

The right to be free from unreasonable dis

criminations belongs, under §3(1), to each particu

lar person. Where a dining car is available to

passengers holding tickets entitling them to use it,

each such passenger is equally entitled to its facili

ties in accordance with reasonable regulations. The

denial of dining service to any such passenger by

the rules before us subjects him to a prohibited dis

advantage. Under the rules, only four Negro pas

sengers may be served at one time and then only at

the table reserved for Negroes. Other Negroes who

present themselves are compelled to await a vacancy

at that table, although there may be many vacancies

elsewhere in the diner. The railroad thus refuses

to extend to those passengers the use of its exist

ing and unoccupied facilities. The rules impose a

like deprivation upon white passengers whenever

more than 40 of them seek to be served at the same

time and the table reserved for Negroes is vacant.

Under the Henderson formula, it is impossible to main

tain segregation in railway dining cars or in any area

of limited space, because no regulation requiring racial

segregation can avoid the possibility that a member of the

segregated group may be denied service or the use of the

facility in question, where space may be available in that

portion of the facilities barred to members of his racial

group.

Application of that reasoning to the instant case would

necessarily condemn the state law here involved. Under

South Carolina law no Negro or white person may occupy

contiguous space on the same seat on appellant’s buses.

To comply with these requirements appellant enforces

regulations which seat white persons front to rear and

11

Negro passengers rear to front, and no Negro may sit

beside or in front of a white person. Thus, a situation

must necessarily occur, as in the instant case, when a seat

is available beside or in front of a white person, and a

Negro passenger must remain standing because all seats

which the regulations permit him to occupy are filled.3

3. That federal jurisdiction exists is clear. Appellee

alleged in her complaint that her action arose under the

fourteenth Amendment and under Title 42, United States

Code, Sections 1981 and 1983 and invoked federal jurisdic

tion under Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343 (3).

Appellee’s basic contention is that Title 58, Section 58-1491

to 58-1496, inclusive, Code of Laws of South Carolina,

1952, set out in Appendix C to appellant’s jurisdictional

statement makes the carrier a state instrumentality for the

enforcement of the state’s policy of segregation on appel

lant’s buses. Further, Sections 58-1402, 58-1403, 58-1406,

58-1422, 15-1461 (cited swpra at pages 4-6) clearly demon

strate that, insofar as enforcement of racial segregation is

concerned, the carrier must enforce the state’s policy or risk

3 It is also of interest that the Interstate Commerce Commission

in the two cases decided on November 7th past, cited ante, which

held that the Interstate Commerce Act bars segregation in inter

state railway coaches, buses and waiting rooms, even though equal

facilities are provided, quotes the following language appearing at

page 825 in the Henderson case in support of its conclusion that seg

regation is a prohibited discrimination under the Interstate Com

merce A ct:

We need not multiply instances in which these rules sanc

tion unreasonable discriminations. The curtains, partitions

and signs emphasize the artificiality of a difference in treat

ment which serves only to call attention to a racial classifica

tion of passengers holding identical tickets and using the same

public dining facility.

12

loss of its right to operate its business within the state.

Unquestionably, appellant was acting under color of law

in promulgating and enforcing regulations designed to

accomplish on its buses the racial segregation required by

state law. Both bus driver and the carrier became the

state’s instruments for the purpose of effecting its policy.

Neither Picking v. Penn R. R. Co., 151 F. 2d 240 (CA

3d 1945), nor Moore v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 98 F.

Supp. 375 (E. D. Pa. 1951), is contrary or in conflict with

the decision below in this case. Apparently, the reason for

their citation is the suggestion in both cases that employ

ees of private corporations engaged in passenger trans

portation could not be held to act under color of law with

out a showing that they conspired with state officials or

purported to act as state officials. As a general statement,

this may well be true, but there was no showing in either

case cited of a statutory scheme which empowered and

required the carrier to enforce the state’s policy. Such

is the situation here. The state requires that intrastate

motor vehicle carriers maintain and enforce segregation in

the operation of their vehicles. The state’s policy could

not be enforced in the abstract, and it delegated to the

carrier the authority to promulgate and enforce regula

tions that would effectuate the statutory policy. For

that purpose, therefore, the carrier necessarily became a

state instrumentality, and as such its action is within the

reach of the Fourteenth Amendment.

13

Conclusion

Wherefore, for the reasons hereinabove indicated, it is

respectfully submitted, the judgment of the Court of

Appeals is correct and this motion to affirm should be

granted.

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

P hilip W ittenberg,

Attorneys for Appellee.

W illiam T aylor,

of Counsel.