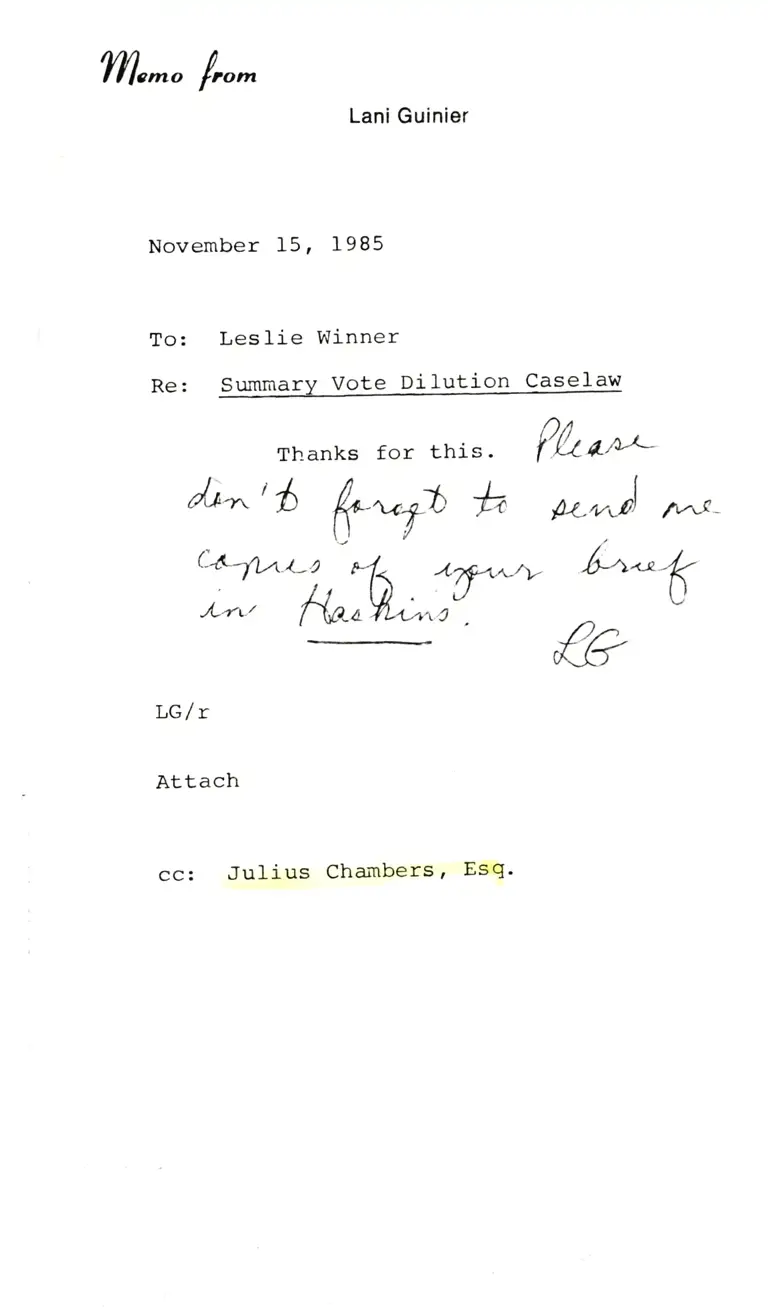

Correspondence from Guinier to Winner; Legal Research on Summary Vote Dilution Caselaw

Working File

November 15, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Correspondence from Guinier to Winner; Legal Research on Summary Vote Dilution Caselaw, 1985. 6d3acb8f-db92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8c1139c0-b5cb-4ba2-b61e-22ff8e4850d9/correspondence-from-guinier-to-winner-legal-research-on-summary-vote-dilution-caselaw. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

T/1"^o f,,^

Lani Guinier

November 15, I985

To: Leslie Winner

Re: Summary Vote Dilution Caselaw

LG /r

Attach

cc: Julius Chambers, Esq'

rhanks ror this - lL"-*

C-++jttO e*

,t-.,, fu^ffi.Y

h-t

{G

SUMMARY VOTE DILUTION CASELAW

t. Gqnillrqn vr t-r-ghEaa!, 364 u.s. 339, 5 t.Ed 2d 1I0, 8I

S.Ct. 125 (1960). The Court held that a claim of gerry

mandering of municipal boundaries to fence out Negro citizens

'so as to deprive them of their pre-existing municipal vote"

stated a claim under the Fifteenth Amendment. fn answering the

assertion that establishment of,municipal boundaries is a purely

political guestion not subject to judicial r.ev,iew, the Court

stated:

When a State exercises power wholly within lhe

domain of state interest, it is insulated from

-

federal judicial review. But such insulation is

not carried over when state power is used as an

instrument for circumventing a federally protected

right.

Id. at 347.

2. Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 7 L.Ed 2d 653, 82 S.Ct.

691 (1962). In the context of a claim that the malapportionment

of the Tennessee legislature violated the egual protection

clause, the Court held that constitutional chalf"rrge. to state

legislative apportionments are not nonjusticable "political

guestions." The nonjusticability of political guestions is

primarily a function of the separation of powers, and the

determination of the consistency of state actions with the

Federal Constitution is r,rithin the realm of the judicial branch.

3. Revnolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, L2 L.Ed 2d 505, 84

S.Ct. 1352 (L9641. In the context of a challenge to the

apportionment of the Alabama legislature, the Court recognized

that voting strength can be unconstitutionally diluted by

creation of legislative districts wj.th highly dispurete numbers

of people residing in each district.

[fJne right of suffrage can be denied by a

debasement or dilution of the weight of a

citizen's vote just as effectively as by wholly

prohibiting .the free exercise of the franchise.

Id. at 555.

The Court's holding that the egual protection clause

reguires that seats in both house of a bicameral state

legislature be apportioned so that each seat has as .near to

egual population as is practical has .cotn. to be known as the

'one person one vote" doctrine. See also Drum v. SeaweII , 250

F.Supp. 922 (M.D.N.C. I965) (holding apportionment of seats in

North Carolina General Assembly to violate one person one vote).

4. White v. Reqis.ter, 4L2 U.S. 755, 93 S.Ct. 2332? 37 L.Ed

2d 314 (1973). Plaintiffs claimed that the use of at large

elections from multimember districts diluted black and hispanic

voting strength by submerging concentrations of minority voters

into larger white electorates. The Court combined the concepts

of unconstitutional exclusion of voters based on race, see

Gomillion v. Lichtfoot, SPIB, with unconstitutional dilution of

voting strengthr s€e Revnolds v. Sims, supra, to hold that

dilution of voting strength of racial minorities as a group

violates the egual protection clause. "The plaintiffs' burden

is to produce evidence to support findings that the political

process leading to nomination and election were not egually open

to participation by the group in guestion - that its members had

less opportunity than did other residents in the district to

participate in the political processes and to elect legislators

of their choice." Id. at 766. The determination is to be made

2-

on "the totality of circumstances'r which is a blend of cultural,

economic and political realities, past and present.

5. Between 1973 and 1980, the.Courts of Appeals fleshed

-'' out the meaning of the White v. Reqlster totality of

circumstances test. See esp. Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d L2g7

(5th Cir. 1973) (en banc) aff'd on other qrounds sub non East

Carroll Parish School Board v. Yarshall, 424 U.S. 536 (1976), in

which the Court articulated what came to be known as "the Zimmer

factors "

5. Citv of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, I00 S.Ct. 1490,

64 L.EF2d 47 (1980). The Court held that the Fifteenth

Amendment prohibits only purposeful denial of the right to vote

because of race and does not entail the right to have black

candidates elected. The Court applied Washinqton v. Davis, 426

U.S. 229 (1975) and Arlinqton Heiqhts v. Metropolitian Housins

Authoritv, 429 U.S. 252 (L97'l ) to claims of racial

discrimination affecting voting and held that dilution of

minority voting strength violates the egual protection clause

only if it is the result of purposeful discrimination against

black voters. Finally, a plurality of the Court held that

section 2 of the voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 u.s.c. s L973,'

had the same seope as the Fifteenth Amendment.

7. The Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, pub.L.No.

97-205, amended Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act to eliminate

the reguirement of proving discriminatory purpose and to

incorporate the totality of circumstances test of White v.

Reqisterr supEdr and its progeny. See legislative history,

3-

Report of the Senate Judiciary Committee on S. 1992, S. Rep. No.

4L7, 97th Con., 2d Sess. (1982).

4-