Timbs v. Indiana Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

September 11, 2018

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Timbs v. Indiana Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners, 2018. 747c8935-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8ca4e7b7-ec29-461b-b476-ad7e31efe050/timbs-v-indiana-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

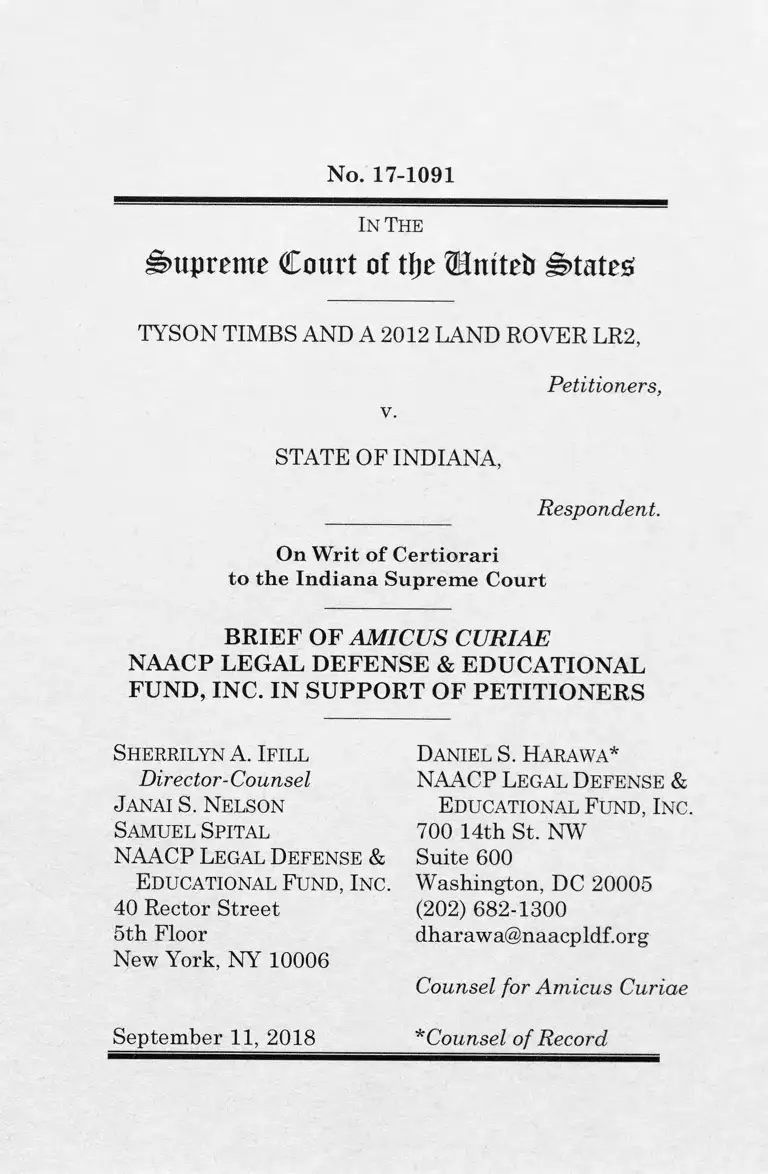

No. 17-1091

In The

mpreme Court of tfje Muttetr States?

TYSON TIMBS AND A 2012 LAND ROVER LR2,

Petitioners,

v.

STATE OF INDIANA,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari

to the Indiana Supreme Court

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

Director-Counsel

Janai S. Nelson

Samuel Spital

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

40 Rector Street

5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

September 11, 2018

Daniel S. Harawa*

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

700 14th St. NW

Suite 600

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

dharawa@naacpldf.org

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

mailto:dharawa@naacpldf.org

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................................ ii

INTERESTS OF AMICUS CURIAE...........................1

INTRODUCTION..........................................................2

ARGUMENT.................................................................. 5

I. THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT WAS

INTENDED TO GUARANTEE IMPORTANT

RIGHTS TO ALL PEOPLE AND TO ACT

AS A GUARD AGAINST STATES ABUSING

THOSE RIGHTS.......................................................5

II. THE FRAMERS WOULD HAVE INTENDED

FOR THE EXCESSIVE FINES CLAUSE TO

APPLY TO THE STATES..................................... 17

III. THE COURT SHOULD MORE CLOSELY

ALIGN ITS PAST INCORPORATION

CASES WITH THE HISTORY ANIMATING

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT................ 22

CONCLUSION.............................................................30

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE IS)

CASES:

Apodaca v. Oregon,

406 U.S. 404 (1972)............................. 4-5, 23-24, 25

Apprendi v. New Jersey,

530 U.S. 466 (2000).................................................... 5

Brown v. Bd. of Educ. of Topeka,

347 U.S. 483 (1954)..... ,............................................. 1

Browning-Ferris Indus, of Vt., Inc. v.

Kelco Disposal, Inc.,

492 U.S. 257 (1989)...................................... 17

The Civil Rights Cases,

109 U.S. 3 (1883).........................................................8

Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1 (1958).........................................................1

Cooper Indus., Inc. v. Leatherman Tool Grp., Inc.,

532 U.S. 424 (2001).................................................. 18

District of Columbia v. Heller,

554 U.S. 570 (2008).................................................... 6

Duncan v. Louisiana,

391 U.S. 145 (1968).................................................... 6

Ill

PAGE(S)

Hurtado u. California,

110 U.S. 516 (1884)............................................. 4, 23

In re Winship,

397 U.S. 358 (1970)................................ .................24

Indiana v. Timbs,

84 N.E.3d 1179 (Ind. 2017).................................... 18

Johnson v. Louisiana,

406 U.S. 356 (1972)..................................................24

Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 (1967).........................................................1

McDonald v. City of Chicago,

561 U.S. 742 (2010)........................................ passim

Minneapolis & St. Louis R.R. v. Bombolis,

241 U.S. 211 (1916)............................................. 4, 23

Parklane Hosiery v. Shore,

439 U.S. 322 (1979)..................................................23

United States v. Bajakajian,

524 U.S. 321 (1998).................................................. 17

United States v. Booker,

543 U.S. 220 (2005).............................................5, 24

United States v. Louisiana,

225 F. Supp. 353 (E.D. La. 1963)...........................26

IV

AMENDMENTS:

PAGE(S)

U.S. Const, amend. VIII.............................................. 19

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

Jack M. Balkin & Reva B. Siegel, The American

Civil Rights Tradition: Anticlassification or

Antisubordination,

58 U. Miami L. Rev. 9 (2004).................................. 14

DeNeen L. Brown, When Portland Banned

Blacks: Oregon’s Shameful History as an

All-White’ State, WASH. POST (June 7, 2017)...... 27

Pamela Chan, et al., Forced to Walk a Dangerous

Line: The Causes and Consequences of Debt in

Black Communities, PROSPERITY Now

(March 2018), https://prosperitynow.org/sites/

default/files/resources/Forced%20to%20

Walk%20a%20Dangerous%20Line.pdf................ 21

Douglas L. Colbert, Liberating the Thirteenth

Amendment,

30 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 1 (1995).........................8

Beth A. Colgan, Reviving the Excessive Fines

Clause, 102 CAL. L. REV. 277 (2014).................... 22

C o n g . G l o b e , 38th Cong., 1st sess. (1864) ............6

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess.

(1866) .............................................. 12, 13, 14, 15, 19

https://prosperitynow.org/sites/

V

CONG. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st sess. (1871)..........16, 29

Council of Economic Advisers Issue Brief,

Fines, Fees, and Bail (Dec. 2015),

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/

default/files/page/files/1215_ceaj:ine_fee_

b ail_is sue Jbr ief. p df.................................................. 19

Crim. Justice Policy Program at Harv.

L. Sch., Confronting Criminal Justice Debt: A

Guide for Policy Reform (Sep. 2016),

http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/Confronting-

Crim-Justice-Debt-Guide-to-Policy-Reform-

PAGE(S)

FINAL.pdf........................................... ...................... 20

Michael Kent Curtis, No State Shall

Abridge: The Fourteenth Amendment

and the Bill of Rights (1986)................. 10, 12, 16

Mika’il DeVeaux, The Trauma of the

Incarceration Experience,

48 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 257 (2013)................. 22

Paul Finkelman, John Bingham and the

Background to the Fourteenth Amendment,

36 Akron L. Rev. 671 (2003)..........................8, 9, 10

Paul Finkelman, This Historical Context

of the Fourteenth Amendment,

13 Temp. Pol. & Civ. Rts. L. Rev. 389

(2004)................................................... 7, 8, 11, 12, 16

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/

http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/Confronting-Crim-Justice-Debt-Guide-to-Policy-Reform-

http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/Confronting-Crim-Justice-Debt-Guide-to-Policy-Reform-

V I

John Hope Franklin, The Civil Rights Act of 1866

Revisited, 41 HASTINGS L.J. 1135 (1990)..............12

Guy Gugliotta, New Estimate Raises Civil War

Death Toll, N.Y. TIMES (Apr. 2, 2012),

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/03/

science/civil-war-toll-up-by-20-percent-

in-new-estimate.html..............................................2

Aliza B. Kaplan & Amy Saack, Overturning

Apodaca v. Oregon Should Be Easy:

Nonunanimous Jury Verdicts in

Criminal Cases Undermine the Credibility

of Our Justice System,

95 OR. L. rev . 1 (2016)......................................27, 28

Dan Kopf, The Fining of Black America,

PRICEONOMICS (June 24, 2017),

https://priceonomics.com/the-fining-of-black-

america/...................................................................... 21

Letter from Jesse Shortess to John Sherman,

John Sherman Papers, Library of Congress,

Washington, D.C. (Dec. 24, 1865)............... ...............

Gerard N. Magliocca, The Father of the 14th

Amendment, N.Y. TIMES (Sept. 17, 2003).............13

PAGE(S)

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/03/

https://priceonomics.com/the-fining-of-black-america/

https://priceonomics.com/the-fining-of-black-america/

PAGE(S)

Katherine D. Martin et al., Shackled to Debt:

Criminal Justice Financial Obligations

and the Barriers to Re-entry They Create,

Harv. Kennedy Sch. & Nat’l Inst, of

Justice (Jan. 2017),

http s ://ww w. ncj r s. go v/p dffiles l/nij/249976.pdf....21

Michael Martinez, et al., Policing for Profit:

How Ferguson’s Fines Violated Rights of

African-Americans, CNN (Mar. 6, 2015),

https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/06/us/ferguson-

missouri-racism-tickets-fines/index.html ........20

William E. Nelson,

The Fourteenth Amendment:

From Political Principle to Judicial

Doctrine (1995)..............................................passim

Roopal Patel & Meghna Philip, Criminal Justice

Debt, A toolkit for Action,

Brennan Ctr. for Justice (2012),

http s ://www .brennancenter .or g/sites/

default/files/legacy/publications/Criminal

%20Justice%20Debt%20Background%20

for%20web.pdf..........................................................22

John Silard, A Constitutional Forecast:

Demise of the “State Action” Limit on the

Equal Protection Guarantee,

66 COLUM. L. rev . 855 (1966)................................ 8

https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/06/us/ferguson-missouri-racism-tickets-fines/index.html

https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/06/us/ferguson-missouri-racism-tickets-fines/index.html

V l l l

PAGE(S)

Robert J. Smith & Bidish J. Sarma,

How and Why Race Continues to Influence

the Administration of Criminal Justice

in Louisiana, 72 La . L. Rev. 361(2012)...........25, 26

Speech of John A. Bingham, In Support of the

Proposed Amendment to Enforce the

Bill of Rights (Feb. 28, 1866),

https ://archive .or g/stream/onecountryonecon

00bing#page/nl.........................................................13

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the

Constitution of the United States

§ 1896 (1833)............................................................. 17

13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution:

Abolition of Slavery, America’s Historical

Documents, N a t ’l ARCHIVES,

http s ://www. archives. go v/historical- docs/

13th-amendment (last visited Sep. 4, 2018)...........7

U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Targeted

Fines and Fees Against Communities

of Color: Civil Rights & Constitutional

Implications (Sept. 2017),

https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/docs/

Statutory_Enforcement_

Report2017.pdf............................................ 20, 21, 22

https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/docs/

INTERESTS OF AMICUS CURLAE

From its earliest advocacy led by Justice

Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc. (“LDF”) has strived to secure

the constitutional promise of equality for all people.

Petitioner asks the Court to consider an important

question about the Fourteenth Amendment’s reach,

which, more than any other constitutional provision,

embodies our Nation’s commitment to equal justice

under the law.

Since its founding close to 80 years ago, LDF has

been at the forefront of efforts to enforce the

Fourteenth Amendment’s promise of equality. See,

e.g., Brown v. Bd. of Educ. of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483

(1954); Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958); Loving v.

Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967). LDF submits this brief to

help the Court decide whether the Fourteenth

Amendment’s Due Process Clause incorporates the

Eighth Amendment’s Excessive Fines Clause. LDF

also submits this brief to propose an approach to

incorporation that more closely aligns with the anti

subordination principle at the core of the Fourteenth

Amendment.1

1 Pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 37.6, counsel for amicus

curiae state that no counsel for a party authored this brief in

whole or in part and that no person other than amicus curiae, its

members, or its counsel made a monetary contribution to the

preparation or submission of this brief. All parties have

consented to the filing of this brief.

2

INTRODUCTION

150 years ago, the Nation faced a defining

moment. A bloody Civil War about whether Southern

States would be able to continue to enslave Black

people had torn the country in two. After defeating

the Confederacy, at a cost of more than 600,000 lives,2

the Union had to devise a way not only to guarantee

formerly enslaved Black people equal rights, but also

to protect these newly-won rights from Southern

aggression.

Congress began by adopting the Thirteenth

Amendment to end slavery, which the States ratified.

The Southern States responded to slavery’s abolition

by enacting the Black Codes—laws designed to

repress African Americans and recreate slavery-like

conditions. To combat the Black Codes, Congress

passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which gave the

Federal Government power to protect the civil rights

of Black Americans. But there was a question of the

Act’s constitutionality, so Congress proposed another

constitutional amendment to remedy that concern:

The Fourteenth Amendment.

The Fourteenth Amendment had two important

purposes. One, it guaranteed equal rights to all people

in all States, particularly African Americans. Two, it

provided the Federal Government with the power to

protect these rights should States try to infringe on

2 See Guy Gugliotta, New Estimate Raises Civil War Death Toll,

N.Y. Times (Apr. 2, 2012),

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/03/science/civil-war-toll-up-

by-20-percent-in-new-estimate.html.

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/03/science/civil-war-toll-up-by-20-percent-in-new-estimate.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/03/science/civil-war-toll-up-by-20-percent-in-new-estimate.html

3

them. Congress designed the Amendment to radically

shift the federal-state balance of power. The States

ratified the Fourteenth Amendment on July 28, 1868.

This Court has held that the first section of the

Fourteenth Amendment incorporates at least some of

the Bill of Rights against the States, although there

has been disagreement over whether incorporation is

proper under the Amendment’s Due Process Clause

or Privileges and Immunities Clause. See McDonald

v. City of Chicago, 561 U.S. 742, 754-767 (2010)

(recounting the various approaches to incorporation).

It is almost universally accepted, however, that the

incorporation analysis must begin by putting the

Amendment in its historical context and examining

the intent of the Framers. See, e.g., id. at 778 (looking

at what the Framers “counted” as a “fundamental

right []”); id. at 842 (Thomas, J., concurring) (looking

at what the Framers “understood”); id. at 863

(Stevens, J., dissenting) (looking at the “historical

evidence” of what the Framers “thought”); id at 918

(Breyer, J., dissenting) (taking “account of the

Framers’ basic reason[ing]”).

The Framers intended the Fourteenth

Amendment to be a bulwark against States infringing

on citizens’ civil rights, with special attention to the

invidious tactics Southern States used to strip African

Americans of their rights. As a result, a critical

question that the Court should ask during an

incorporation inquiry is whether the right at issue

protects against the kind of tactics Southern States

used to repress Black people in the post-Civil War

4

period. If the right does, then the Framers would have

intended for it to be incorporated against the States.

Under this test, the Court should hold that the

Eighth Amendment Excessive Fines Clause is

incorporated against the States. The Framers would

have intended the constitutional protection against

disproportionate financial punishment to apply

equally across the country to ensure that States do

not use debilitating fines and forfeitures as a tool to

subjugate citizens.

The framework proposed in this brief also opens

the door to reexamining other aspects of this Court’s

incorporation doctrine. Given that the Court has

recognized a shift in its incorporation jurisprudence,

and has incorporated most of the Bill of Rights, see

McDonald, 561 U.S. at 764-65 & n.12, the Court

should take the opportunity in appropriate cases to

revisit its rulings refusing to incorporate three of the

Bill of the Rights’ guarantees. See Hurtado v.

California, 110 U.S. 516 (1884) (refusing to

incorporate Fifth Amendment’s Grand Jury Clause);

Minneapolis & St. Louis R.R. v. Bombolis, 241 U.S.

211 (1916) (same for Seventh Amendment civil jury

trial right); Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404 (1972)

(same for Sixth Amendment unanimous jury verdict

right).

Most pressing is the need for the Court to revisit

Apodaca—its decision refusing to incorporate the

Sixth Amendment right to a unanimous jury verdict

in a criminal trial. Apodaca is inconsistent with this

Court’s current jurisprudence, as eight of the Justices

5

in Apodaca believed the Sixth Amendment applied to

the States and the Federal Government equally, and

the Court has repeatedly held the Sixth Amendment

requires unanimity in federal criminal trials. See, e.g.,

United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220, 230 (2005);

Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466, 476 (2000).

Moreover, the Apodaca plurality opinion was based

on the notion that there was no “proof’ unanimity was

needed to protect defendants from prejudice and

ensure minority jurors have a voice during

deliberations. Yet Louisiana and Oregon, the only

states with non-unanimous jury provisions,

specifically enacted the provisions to silence minority

jurors and more easily convict minority defendants.

Applying the incorporation lens proposed in this brief

confirms that Apodaca was wrongly decided.

ARGUMENT

I. THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT WAS

INTENDED TO GUARANTEE IMPORTANT

RIGHTS TO ALL PEOPLE AND TO ACT AS

A GUARD AGAINST STATES ABUSING

THOSE RIGHTS.

In recent years, when determining whether to

incorporate a provision of the Bill of Rights, the Court

has put itself in the shoes of the “Framers and

ratifiers of the Fourteenth Amendment” and asked

whether they would have intended to incorporate the

right against the States to maintain “our system of

ordered liberty.” McDonald, 561 U.S. at 778. When

undertaking this inquiry, the Court has considered

6

contemporaneous congressional statements.3 It has

also placed the Amendment in context by looking at

the “history that the [framing] generation knew.”

District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 598

(2008).4 Thus, the starting place for an incorporation

question is the history of the Fourteenth Amendment.

After the Civil War, “Congress was [called] to

devise a formula, in which the South would acquiesce,

‘to secure in a more permanent form the dear bought

victories achieved in the mighty conflict.”’5 As

Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson said, the goal

was to ensure that “the curse of civil war may never

be visited upon us again.”6 The Reconstruction

Congress was determined to secure “lawful liberty”

3 See, e.g., McDonald, 561 U.S. at 772 (quoting statements of Sen.

Henry Wilson); id. at 775 (quoting statements of Rep. John

Bingham); id. (quoting statements of Sen. Samuel Pomeroy);

District of Colum bia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 616 (2008) (quoting

statements of Sen. Davis and Rep. Nye).

4 See also McDonald, 561 U.S. at 745 (taking a “survey of the

contemporaneous history” of the Fourteenth Amendment); id. at

762 (looking at “[e]vidence from the period immediately

following the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment”);

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 155-56 (1968) (looking at the

“history and experience” of “ [t] hose who wrote our constitutions,”

when deciding whether the Sixth Amendment jury trial right is

incorporated against the States).

5 William E. Nelson, The Fourteenth Amendment: From

Political Principle to Judicial Doctrine 44 (1995) (quoting

Governor’s Message, Des Moines Iowa State Register, p.3 col. 7

(Jan. 15, 1868)).

6 CONG. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st sess. 1203 (1864) (statement of

Sen. Henry Wilson).

7

“in all the states of the Union, and to all the people,

white and black alike.”7

To that end, almost immediately after the War,

the country ratified the Thirteenth Amendment,

abolishing slavery.8 Still, the Southern States were

unwilling to end the institution. As one Southern

legislator wrote Ohio Senator John Sherman, the

South was “determined to do by policy what fit] had

failed to do with arms.”9 Although many Southern

whites “conceded that blacks were no longer slaves of

individual masters,” they “intended to make them

slaves of society.”10 As a Union Army commander in

Virginia put it: Southern whites wanted to reduce

Black people “to a condition which will give the former

masters all the benefits of slavery, and throw upon

them none of its responsibilities.”11

7 NELSON, supra note 5, at 43 (quoting The Source of Mr. Steven’s

Power, N.Y. EVENING POST, p.3 col 1 (Mar. 14, 1866)).

8 See 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Abolition of

Slavery, America’s Historical Documents, Nat’L ARCHIVES,

https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/13th-amendment (last

visited Sep. 4, 2018).

9 NELSON, supra note 5, at 41 (Letter from Jesse Shortess to John

Sherman, JOHN SHERMAN PAPERS, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS,

Washington, D.C. (Dec. 24, 1865)).

10 Paul Finkelman, This Historical Context of the Fourteenth

Amendment, 13 Temp. POL. & ClV. RTS. L. Rev. 389, 400 (2004)

(quotation marks omitted) (“Historical Context”).

11 NELSON, supra note 5, at 43.

https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/13th-amendment

8

To recreate a slavery-like existence, between 1865

and 1866,12 Southern States passed “infamous black

codes,”13 “designed to replicate, as closely as possible,

the pre-war suppression and exploitation of blacks.”14

“The Black Codes represented a legalized form of

slavery in which each southern state perpetuated the

master-slave relationship by passing apprenticeship

laws, labor contract laws, vagrancy laws and

restrictive travel laws . . . denying African Americans

civil rights and due process of law.”15

For example, Louisiana passed a law resembling

“antebellum fugitive slave laws,” which made it a

crime to “persuade or entice away, feed, harbor or

secret any person who leaves his or her employer.”16

12 See John Silard, A Constitutional Forecast: Demise of the

“State Action” Limit on the Equal Protection Guarantee, 66

COLUM. L. REV. 855, 869 (1966).

13 NELSON, supra note 5, at 43.

14 Finkelman, Historical Context, supra note 10, at 402. See also

The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, 36-37 (1883) (Harlan, J.,

dissenting) (“Recall the legislation of 1865-66 in some of the

States, of which this court, in the Slaughterhouse Cases, said

that it imposed upon the colored race onerous disabilities and

burdens; curtailed their rights in the pursuit of life, liberty, and

property to such an extent that their freedom was of little value;

forbade them to appear in the towns in any other character than

menial servants; required them to reside on and cultivate the

soil, without the right to purchase or own it; excluded them from

many occupations of gain; and denied them the privilege of

giving testimony in the courts where a white man was a party.”).

15 Douglas L. Colbert, Liberating the Thirteenth Amendment, 30

HARV. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 1, 55 n.62 (1995).

16 Paul Finkelman, John Bingham and the Background to the

Fourteenth Amendment, 36 AKRON L. Rev. 671, 681-82 (2003)

(quotation marks omitted).

9

Mississippi passed a law requiring Black people to

“have a lawful home or employment” and then passed

a vagrancy law that “allowed government authorities

to auction off . . . any black who did not have a labor

contract.”17 Georgia passed a vagrancy law that

allowed “vagrants” to be “arrested and sentenced to

work on the public roads . . . or be bound-out for up to

a year to someone.”18 And Alabama’s vagrancy law

“allowed for the incarceration in the public workhouse

of any laborer or servant who loiters away his time, or

refuses to comply with any contract for a term of

service without just cause.”19 These laws, and many

others like them, created a “new system of forced

labor,” reducing Black people “to a status somewhere

between that of slaves (which they no longer were)

and full free people (which most white southerners

opposed).”20

The Southern campaign to subjugate Black

people was not limited to repressive laws. It also

included horrific and widespread violence. To that

point, in 1866, several U.S. Military leaders testified

to Congress about the pervasive violence perpetrated

by whites against Blacks in the former Confederacy.

Major General Clinton Fisk testified about Southern

whites pursuing Black people “with vengeance and

treat[ing] them with brutality.”21 Major General

17 Id. at 683 (quotation marks omitted).

18 Id. (quotation marks omitted).

19 Id. at 684 (quotation marks omitted).

20 Id. at 685 (parentheticals omitted).

21 Id. at 688.

10

Edward Hatch testified that Black people understood

that they were “not safe from the poor whites,” and

that if they resisted the “reestablishment of bondage

then they were liable to be shot.”22 When Lieutenant

Colonel R.W. Barnard was asked if it was safe to

remove Union troops from Tennessee, he responded

by relating what someone else had told him: “I tell you

what, if you take away the military from Tennessee,

the buzzards can’t eat up the niggers as fast as we’ll

kill 'em.”23 Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner

received a “box containing the finger of a black man,”

with a note that read, “‘You old son of a bitch, I send

you a piece of one of your friends.’”24

White abolitionists and Union sympathizers also

faced Southern aggression.25 White people were

“thrown into prison” for telling freed Black people

“they were rightfully entitled to vote.”26

Massachusetts Representative Benjamin Butler

described the dire situation: “Northerners could not

go South and argue the principles of free government

without fear of the knife or pistol, or of being

murdered by a mob.”27

It was against this backdrop the Reconstruction

Congress was compelled to act. It was clear that the

22 Id. at 687-88. (quotation marks omitted).

23 Id. at 688 (quotation marks omitted).

24 Id. at 685.

25 See, e.g., Michael Kent Curtis, No State Shall Abridge:

The Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of Rights 136

(1986).

26 Id. at 135-36.

27 NELSON, supra note 5, at 42 (quotation marks omitted).

11

Thirteenth Amendment could not sufficiently protect

the rights of African Americans, and that a shift in

the federal-state power balance was needed if Black

people were to be protected. Thus, in December 1865,

Congress formed the Joint Committee on

Reconstruction. The Committee consisted of six

Senators and nine Congressmen, who were charged

with “investigat[ing] conditions in the South.”28 As

part of its investigation, the Committee “interviewed

scores of people—former slaves, former confederate

leaders and slave owners, United States Army

officers, and others in the South.”29

Out of this Committee came the country’s first

attempt to pass a law aimed at remediating the

abuses perpetrated in the South under the Black

Codes—the Civil Rights Act of 1866.30 The Act

declared that “all persons” “of every race and color,

without regard to any previous condition of slavery or

involuntary servitude . . . shall have the same right[s]

in every State and Territory in the United States” and

“full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings . . .

as enjoyed by white citizens.”31

There were widespread concerns with the Act,

however. Some, including President Andrew Johnson,

questioned its constitutionality, believing that “the

Constitution did not confer on Congress the power to

28 Finkelman, Historical Context, supra note 10, at 400.

29 Id.

30 Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, 14 Stat. 27.

31 Id. § 1.

12

make rules to regulate the acts of states.”32 A

contingent of congressmen agreed with President

Johnson and bemoaned this lack of power,

complaining that “the citizens of the South and of the

North going South have not hitherto been safe in the

South, for want of constitutional power in Congress to

protect them.”33 Others thought that the Act, even if

constitutional, did not go far enough; that the Act’s

protections could be easily rescinded should the

political winds change.34

The Joint Committee thus did not stop with the

Civil Rights Act. It also proposed a constitutional

amendment.35 “ [T]he Committee concluded that

nothing short of a Constitutional amendment—what

became the Fourteenth Amendment—would protect

the rights of the former slaves.”36 The Committee

knew it was “framing an amendment of our

fundamental law, which may exist for centuries

without change.”37 The Committee also understood it

was “making history, and laying foundations for our

future national building.”38 This was going to be the

amendment that “securjed] the fruits both of the war

and of the three decades of antislavery agitation

32 John Hope Franklin, The Civil Rights Act of 1866 Revisited,

41 Hastings L.J. 1135,1136 (1990).

33 CURTIS, supra note 25, at 138-139.

34 See CURTIS, supra note 25, at 55, 62-63, 86.

35 Finkelman, Historical Context, supra note 10, at 400.

36 Id. at 401.

37 CONG. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess. 385 (1866) (statement of

Rep. Jehu Baker).

38 NELSON, supra note 5, at 45 (quotation marks omitted).

13

proceeding it.”39 To meet these goals, the Framers

designed the amendment to: (1) guarantee all people,

especially Black people, the privileges enshrined in

the Bill of Rights, and (2) protect citizens’ rights from

potential State abuse.

When debating the proposed amendment, Ohio

Congressman John Bingham—“The Father” of the

Fourteenth Amendment40—explained that “the

States of the Union [] have flagrantly violated the

absolute guarantees of the Constitution of the United

States to all its citizens.”41 He therefore declared that

it was “time that [they] take security for the future,

so that like occurrences may not again arise to

distract our people and finally to dismember the

Republic.”42

Bingham later gave a speech “[i]n support of the

proposed amendment to enforce the Bill of Rights.”43

Bingham made clear that an animating feature of the

proposed amendment was that it would prohibit

legislation “and practices that reduce groups to the

39 NELSON, supra note 5, at 61.

40 Gerard N. Magliocca, The Father of the 14th Amendment, N.Y.

Times (Sept. 17, 2003),

https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/09/17/the-father-of-

the-14th-amendment/.

41 CONG. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess. 158 (1866) (statement of

Rep. John Bingham).

42 Id.

43 Id. at 1088; see Speech of John A. Bingham, In Support of the

Proposed Amendment to Enforce the Bill of Rights (Feb. 28,

1866),

https://archive.Org/stream/onecountryonecon00bing#page/nl.

https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/09/17/the-father-of-the-14th-amendment/

https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/09/17/the-father-of-the-14th-amendment/

https://archive.Org/stream/onecountryonecon00bing%23page/nl

14

position of a lower or disfavored caste.”44 Bingham

declared that the amendment was “essential to the

safety of all people of every State” as it “arm[s] the

Congress of the United States, by the consent of the

people of the United States, with the power to enforce

the bill of rights as it stands in the Constitution

today.”45

Other key congressmen described the proposed

amendment similarly. Representative Thaddeus

Stevens explained that up until that point, the

“Constitution limit[ed] only the action of Congress,

and [was] not a limitation on the States. This

amendment supplies that defect. . . ,”46 Senator Jacob

Howard of Michigan pointed out that there was “no

power given in the Constitution to enforce and to

carry out any of the [Bill of Rights’] guarantees.”47

Thus, the “great object” of the proposed amendment

was “to restrain the power of the States and compel

them at all times to respect these great fundamental

guarantees.”48 Illinois Representative Jehu Baker put

a finer point on why Congress needed to pass the

amendment, asking, “What business is it of any State

44 Jack M. Balkin & Reva B. Siegel, The American Civil Rights

Tradition: Anticlassification or Antisuh or dination, 58 U. MIAMI

L. REV. 9, 9-10 & n.5 (2004).

45 CONG. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess. 1088 (1866) (statement of

Rep. John Bingham).

46 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess. 2459 (1866) (statement of

Rep. Thaddeus Stevens).

47 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess. 2765 (1866) (statement of

Sen. Jacob Howard).

48 Id. at 2766.

15

to do things here forbidden [by the Bill of Rights]? [T]o

rob the American citizen of rights thrown around him

by the supreme law of the land?”49 Baker went on:

“When we remember to what an extent this has been

done in the past, we can appreciate the need of

putting a stop to it in the future.”50

Representative Bingham eloquently summed up

the State abuses that made the protections embodied

in the Fourteenth Amendment necessary:

The States never had the right, though

they had the power, to inflict wrongs

upon free citizens by a denial of the full

protection of the laws . . . . [T] he States

did deny to citizens the equal protection

of the laws, they did deny the rights of

citizens under the Constitution, and

except to the extent of the express

limitations upon the States . . . the citizen

had no remedy. They denied trial by jury,

and he had no remedy. They took

property without compensation, and he

had no remedy. They restricted the

freedom of the press, and he had no

remedy. They restricted the freedom of

speech, and he had no remedy. They

restricted the rights of conscience, and he

49 CONG. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess. app’x at 256 (1866)

(statement of Rep. Jehu Baker).

50 Id.

16

had no remedy. They bought and sold

men who had no remedy. 51

Bingham concluded by explaining that the

Constitution, with the ratification of the Fourteenth

Amendment, now provided a remedy against such

abuses:

Who dare say, now that the Constitution

has been amended, that the nation

cannot by law provide against all such

abuses and denials of right as these in

States and by States, or combinations of

persons? 52

In short, the Fourteenth Amendment’s historical

context shows that the Framers’ “goals were sweeping

and broad.”53 And, after much debate, the Thirty-

Ninth Congress adopted the Fourteenth Amendment,

reflecting discontent “with the protection individual

liberties had received from the states” and “increased

concern for the rights of blacks.”54 Congress wanted

citizens, especially Black citizens, to be “shielded from

hostile state action.”55 And to achieve these goals,

Congress, by passing the Fourteenth Amendment,

“significantly altered our system of government.”

McDonald, 561 U.S. at 807.

51 CONG. Globe, 42d Cong.. 1st sess. app’x at 85 (1871).

(statement of Rep. John Bingham).

52 Id.

53 Finkelman, Historical Context, supra note 10, at 409.

54 CURTIS, supra note 25, at 91.

55 Id.

17

II. THE f r a m e r s w o u l d h a v e in t e n d e d

FOR THE EXCESSIVE FINES CLAUSE TO

APPLY TO THE STATES.

With this history in mind, this Court should hold

that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporates the

Excessive Fines Clause. Because the Clause protects

against abusive governmental practices of the kind

commonly used to subjugate Black people in the post-

Civil War period, the Framers would have intended

its protections to apply against the States.

The Court has explained that the Excessive Fines

Clause “was taken verbatim from the English Bill of

Rights of 1689.” United States v. Bajakajian, 524 U.S.

321, 335 (1998) (citing Browning-Ferris Indus, of Vt.,

Inc. v. Kelco Disposal, Inc., 492 U.S. 257, 266-267

(1989)). And the Excessive Fines Clause in the

English Bill of Rights “was a reaction to the abuses of

the King’s judges during the reigns of the Stuarts.” Id.

The Founders included the Clause in the U.S.

Constitution “as an admonition . . . against such

violent proceedings, as had taken place in England,”

including “ [ejnormous fines and amercements [that]

were . . . sometimes imposed.”56 Based on this history,

this Court emphasized that the “primary focus of the

[Eighth] Amendment is [to protect against] the

potential for governmental abuse of its prosecutorial

power.” Browning-Ferris, 492 U.S. at 266 (emphasis

added).

56 Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the

United States § 1896, at 750-51 (1833).

18

The goal of the Eighth Amendment was to protect

against the Government unfairly wielding its power

to punish citizens. This was also a key concern of the

Fourteenth Amendment. The Framers were aware of

the evils that attend the unchecked ability to mete out

punishment, and therefore intended the Fourteenth

Amendment to protect against it. The Framers no

doubt would have wanted the Eighth Amendment’s

protection against excessive punishment—including

excessive fines—to extend to the States. Consistent

with what the Framers intended, the Court has said

that the Fourteenth Amendment “makes the Eighth

Amendment’s prohibition against excessive fines and

cruel and unusual punishments applicable to the

States.” Cooper Indus., Inc. v. Leatherman Tool Grp.,

Inc., 532 U.S. 424, 433-34 (2001).57

The Framers made their intent of incorporating

the entire Eighth Amendment clear when debating

the reach of the Fourteenth Amendment. Throughout

the debates, congressmen repeatedly highlighted the

concern of States using exorbitant punishment to

suppress Black people with no federal recourse. For

example, as Representative Bingham said when

closing debate on the Fourteenth Amendment: “cruel

and unusual punishments have been inflicted under

State laws within this Union upon citizens not only

for crimes committed, but for sacred duty done, for

which and against which the Government of the 57

57 The Indiana Supreme Court believed this was dictum. See

Indiana u. Timbs, 84 N.E.3d 1179, 1182 (Ind. 2017), cert,

granted, 138 S. Ct. 2650 (2018) (Mem.).

19

United States had no provided remedy and could

provide none.”58

The concerns of the Fourteenth Amendment’s

Framers about States meting out unjust punishment

did not turn on what form the punishment took. In

other words, the Framers did not exalt the Eighth

Amendment’s protection against “cruel and unusual

punishments” over its protections against “excessive

bail” or “excessive fines.” See U.S. Const, amend. VIII.

The Framers believed that all unjust punishment—

especially punishment targeted at disenfranchising

Black people—was abhorrent. Bingham did not mince

words on this point, declaring “ [i]t was an opprobrium

to the Republic that for fidelity to the United States

[that citizens] could not by national law be protected

against the degrading punishment inflicted on slaves

and felons by State law.”59 The Fourteenth

Amendment repaired this injustice by “striking]

down those State rights and investing] all power in

the General Government.”60

The need for the Excessive Fines Clause to apply

to the States is underscored by the fact that today,

state and local governments increasingly use fines to

punish crime.61 The money from the fines is then used

58 CONG. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess. 2542 (1866) (statement of

Rep. John Bingham) (internal quotation marks omitted).

59 Id. at 2543.

60 Id. at 2500 (statement of Rep. George Shanklin).

61 See Council of Economic Advisers Issue Brief, Fines,

Fees, and Bail at 2-3 (Dec. 2015),

20

to fund local government.62 As a result, the incentive

to punish petty crime with excessive fines is greater

than before.63 And compounding the harm, state and

local governments are disparately imposing these

fines against Black Americans and other people of

color.64 This type of discriminatory punishment is the

kind of wrong the Framers designed the Fourteenth

Amendment to protect against.

Last fall, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

issued a report entitled Targeted Fines and Fees

Against Communities of Color.65 One of the Report’s

key findings was that “unchecked discretion [and]

stringent requirements to impose fines or fees can

lead and have led to discrimination and inequitable

access to justice when not exercised in accordance

with protections afforded under [the Constitution] ,”66

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/fil

es/1215_cea_fine_fee_bail_issue_brief.pdf.

62 Crim. Justice Policy Program at Harv. L. Sch.,

Confronting Criminal Justice Debt: A Guide for Policy

Reform at 1 (Sep. 2016),

http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/Confronting-Crim-Justice-

Debt-Guide-to-Policy-Reform-FINAL.pdf.

es Id.

64 See, e.g., Michael Martinez, et al., Policing for Profit: How

Ferguson’s Fines Violated Rights of African-Americans, CNN

(Mar. 6, 2015), https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/06/us/ferguson-

missouri-racism-tickets-fines/index.html.

65 U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Targeted Fines and Fees

Against Communities of Color: Civil Rights &

Constitutional Implications (Sept. 2017),

https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/docs/Statutory_Enforcement_Repor

t2017.pdf.

66 Id. at 71.

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/fil

http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/Confronting-Crim-Justice-Debt-Guide-to-Policy-Reform-FINAL.pdf

http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/Confronting-Crim-Justice-Debt-Guide-to-Policy-Reform-FINAL.pdf

https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/06/us/ferguson-missouri-racism-tickets-fines/index.html

https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/06/us/ferguson-missouri-racism-tickets-fines/index.html

https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/docs/Statutory_Enforcement_Repor

21

The Report noted that since the 1980s, States and

municipalities have increasingly used fines and fees

as punishment for “low-level offenses” to “generate

revenue.”67 The jurisdictions that use fines as a

revenue source often “have a larger percentage of

African Americans and Latinos relative to the

demographics of the median municipality.”68 One

article that the Report cited found that there was “one

demographic that was most characteristic of cities

that levy large amounts of fines on their citizens: a

large African American population.”69

The amount of criminal debt people face today is

staggering—“some 10 million people owe more than

$50 billion from contact with the criminal justice

system.”70 Failure to pay this debt has debilitating

67 Id. at 7.

68 Id. at 22. One study, after sampling “local governments in nine

thousand cities,” found that “fines and fees contribute to the

revenue for roughly 86% of cities and are higher in locales with

larger Black populations.” Moreover, “[c]ities that have larger

Black populations generate $12-$ 19 more in revenue from fees

and fines per person, compared to those with smaller shares of

Black citizens.” Pamela Chan, et ah, Forced to Walk a Dangerous

Line: The Causes and Consequences of Debt in Black

Communities, PROSPERITY Now at 10 (March 2018),

https://prosperitynow.org/sites/default/files/resources/Forced%2

0to%20Walk%20a%20Dangerous%20Line.pdf.

69 Dan Kopf, The Fining of Black America, PRICEONOMICS (June

24, 2017), https://priceonomics.com/the-fining-of-black-america/.

70 Katherine D. Martin et al., Shackled to Debt: Criminal Justice

Financial Obligations and the Barriers to Re-entry They Create,

Harv. Kennedy Sch. & Nat’l Inst, of Justice at 5 (Jan. 2017),

https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffilesl/nij/249976.pdf.

https://prosperitynow.org/sites/default/files/resources/Forced%252

https://priceonomics.com/the-fining-of-black-america/

https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffilesl/nij/249976.pdf

22

consequences,71 including “driver license suspension,

which presents a significant barrier to employment”;

“bad credit reports that can keep a family from

renting or purchasing a home”; “and in some cases,

jail time.”72 And people who are jailed for criminal

debt must face all the residual effects, including the

trauma of being “locked in a cage”73 “torn away from

their communities and families”74; and the difficulty

of “maintaining employment,” making it harder (if not

impossible) to survive financially once released.75

Simply, the need for the Eighth Amendment to

protect citizens from excessive fines is as evident

today as it was in 1868. In line with the intent of the

Framers, the Court should hold that the Fourteenth

Amendment incorporates the Eighth Amendment’s

Excessive Fines Clause.

III. THE COURT SHOULD MORE CLOSELY

ALIGN ITS PAST INCORPORATION CASES

WITH THE HISTORY ANIMATING THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

The Court has recognized that there has been a

shift in its incorporation jurisprudence. Particularly,

71 See Beth A. Colgan, Reviving the Excessive Fines Clause, 102

CAL. L. Rev. 277, 290-95 (2014).

72 U.S. COMM’N ON Civil Rights, supra note 65, at 35-36.

73 Mika’il DeVeaux, The Trauma of the Incarceration Experience,

48 HARV. C.R.-C.L. L. rev . 257, 257 (2013).

74 Roopal Patel & Meghna Philip, Criminal Justice Debt, A

toolkit for Action, BRENNAN CTR. FOR JUSTICE at 6 (2012),

http s://www .brennancenter. or g/ sites/default/files/legacy/publica

tions/Criminal%20Justice%20Debt%20Background%20for%20

web.pdf.

73 Id.

23

the Court has “shed any reluctance to hold that rights

guaranteed by the Bill of Rights me[e]t the

requirements for protection under the Due Process

Clause.” See McDonald, 561 U.S. at 764-65. This brief

offers a more uniform approach to incorporation,

which would also open a door to reexamining prior

decisions refusing to incorporate certain provisions of

the Bill of Rights.

When appropriate, the Court should revisit its

cases refusing to incorporate the Fifth Amendment’s

Grand Jury Clause and Seventh Amendment civil

jury trial right. See Hurtado, 110 U.S. 516 (refusing

to incorporate the Fifth Amendment’s Grand Jury

Clause); Minneapolis & St. Louis R.R., 241 U.S. 211

(same for Seventh Amendment civil jury trial right).

The Founders believed that both rights were critical

guards against oppressive government power;76 the

Court should therefore reconsider whether they apply

against the States.

Even more pressing, the Court should grant

certiorari in an appropriate case to revisit its decision

refusing to incorporate the Sixth Amendment’s

unanimous jury verdict right. Apodaca, 406 U.S. 404

76 See Hurtado, 110 U.S. at 549, 558 (Harlan, J., dissenting)

(explaining that the Founders “jealously guarded” the grand jury

right because it “secures [a defendant] against unfounded

accusation”); Parklane Hosiery v. Shore, 439 U.S. 322, 343 (1979)

(Rehnquist, J., dissenting) (“The founders of our Nation

considered the right of trial by jury in civil cases an important

bulwark against tyranny and corruption, a safeguard too

precious to be left to the whim of the sovereign, or, it might be

added, to that of the judiciary.”).

24

(plurality op.).71 Apodaca is no longer compatible with

this Court’s case law, and it is sharply inconsistent

with the incorporation framework proposed in this

brief.

In Apodaca, “eight Justices agreed that the Sixth

Amendment applies identically to both the Federal

Government and the States.” McDonald, 561 U.S. at

766 n.14. And this Court recently reiterated that the

Sixth Amendment requires unanimity in federal

criminal trials. See Booker, 543 U.S. at 230 (“It has

been settled throughout our history that the

Constitution protects every criminal defendant

‘against conviction except upon proof beyond a

reasonable doubt of every fact necessary to constitute

the crime with which he is charged.’” (quoting In re

Winship, 397 U.S. 358, 364 (1970)). Thus, if eight of

the Justices in Apodaca agreed that the Sixth

Amendment applies identically to both the Federal

Government and the States, applying the Court’s case

law, unanimous jury verdicts should also be required

in state criminal trials. Apodaca does not make sense

considering this Court’s established law.

The Court should also revisit Apodaca because it

is inconsistent with the intent of the Framers, who

were particularly concerned with state practices that

subjugate African Americans. The Apodaca plurality

was based on a misapprehension of the protections

unanimity provides against racial and ethnic 77

77 Apodaca was decided the same day as Johnson v. Louisiana,

406 U.S. 356 (1972). Johnson held the Fourteenth Amendment

did not itself require unanimity in state criminal trials.

25

prejudice infecting jury trials. Petitioners in Apodaca

argued that unanimity protects against the silencing

of minority jurors, and ensures convictions are based

on evidence and not animus. See Apodaca, 406 U.S. at

412-13. The plurality rejected this argument because

it “simply [found] no proof for the notion that a

majority will disregard its instructions and cast its

votes for guilt or innocence based on prejudice rather

than the evidence.” Id. at 413-14. Nor would the

plurality “assume that the majority of the jury will

refuse to weigh the evidence and reach a decision

upon rational grounds . . . or that a majority will

deprive a man of his liberty on the basis of prejudice

when a minority is presenting a reasonable argument

in favor of acquittal.” Id.

But the history of Louisiana and Oregon’s non

unanimity provisions reveals that the plurality was

mistaken. Both states’ provisions were enacted with

discriminatory intent and were designed to facilitate

convictions over the dissent of minority jurors.

Louisiana adopted its non-unanimity provision

during the state’s 1898 Constitutional Convention. As

two scholars summarized: “the sinister purpose of the

Convention was to create a racial architecture in

Louisiana that could circumvent the Reconstruction

Amendments and marginalize the political power of

black citizens.”78 The Chair of the Convention’s

78 Robert J. Smith & Bidish J. Sarma, How and Why Race

Continues to Influence the Administration of Criminal Justice in

Louisiana, 72 La. L. Rev. 361, 374-75 (2012).

26

Judiciary Committee, Judge Thomas Semmes, openly

declared that the Convention’s purpose was “to

establish the supremacy of the white race.”79 “The

Convention of 1898 interpreted its mandate from the

[Louisiana] people to be, to disfranchise as many

Negroes and as few whites as possible.” United States

v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353, 371 (E.D. La. 1963).

Contemporaneous accounts reveal the purpose of

the non-unanimous jury provision adopted at the

Convention was to silence the voices of Black jurors.

The provision would also make it easier for juries to

convict Black people. One local newspaper espoused

that “ [a]s a juror, [a Black person] will follow the lead

of his white fellows in causes involving distinctive

white interests; but if a negro be on trial for any

crime, he becomes at once his earnest champion, and

a hung jury is the usual result.”80 Another

“commentator went so far as to claim that criminals

would simply not be convicted because of the African-

American presence in the jury box.”81 It was also

widely believed that Black people were not of “much

advantage in any capacity in the courts of law”

because they were “ignorant, incapable of

determining credibility, and susceptible to bribery.”82

79 Id. at 375 (quoting Official Journal of the Proceedings of the

Constitutional Convention of the State of Louisiana: Held in New

Orleans, Tuesday, February 8, 1898, at 374 (1898)).

80 Id. at 375 (quoting Future of the Freedman, DAILY PICAYUNE,

Aug. 31, 1873, at 5).

81 Id. at 376 (citing The Present Jury System, DAILY PICAYUNE,

Apr. 20, 1870, at 4). ■

82 Id. at 375-76.

27

These were the sentiments that sparked Louisiana to

adopt its non-unanimity provision.

The history of Oregon’s non-unanimous jury

provision is no better. In the late 1920s and early

1930s, Oregon was in a “deep [] recession and caught

up in the growing menace of organized crime and the

bigotry and fear of minority groups.”83 Oregon was a

“society where racism, religious bigotry, and anti

immigrant sentiments were deeply entrenched in the

laws, culture, and social life.”84

Amid all this, there was a high-profile murder

trial. Jacob Silverman, a Jewish man, was charged

with shooting Jimmy Walker, a Protestant.85 The jury

convicted Silverman of manslaughter and hung on

the murder charge 11-1 in favor of conviction.86

Silverman was sentenced to three years in prison and

fined $1000.87

83 Aliza B. Kaplan & Amy Saack, Overturning Apodaca v. Oregon

Should Be Easy: Nonunanimous Jury Verdicts in Criminal

Cases Undermine the Credibility of Our Justice System, 95 Or.

L. REV. 1, 4 (2016) (quotation marks omitted).

84 Id. at 4 (quotation marks and brackets omitted). One stark

example of Oregon’s bigoted past: Black people were banned

altogether from the state in the mid-1800s. See DeNeen L.

Brown, When Portland Banned Blacks: Oregon’s Shameful

History as an ‘All-White’ State, WASH. POST (June 7, 2017),

https://www.washingtonpost.eom/news/retropolis/wp/2017/06/0

7/when-portland-banned-blacks-oregons-shameful-history-as-

an-all-white-state/?utm_term=.a8d842e8ea01.

85 Kaplan & Saack, supra note 83, at 3.

86 Id. at 3-4.

87 Id. at 5.

https://www.washingtonpost.eom/news/retropolis/wp/2017/06/0

28

In response, the Oregon legislature “proposed a

constitutional amendment allowing nonunanimous

verdicts.”88 Articles in the local paper, The Morning

Oregonian, highlighted the bigoted roots of the

proposed amendment. One article specifically cited

the Silverman case as coming “at exactly the right

time to bring unprecedent pressure to bear upon the

legislature.”89 Said another article, “Americans have

learned, with some pain, that many peoples in the

world are unfit for democratic institutions, lacking

the traditions of the English-speaking peoples.”90 Yet

another article lamented the “increased urbanization

of American life” as “the vast immigration into

America from southern and eastern Europe, of people

untrained in the jury system, have combined to make

the jury of twelve increasingly unwieldy and

unsatisfactory.”91

Both Louisiana and Oregon’s non-unanimous jury

provisions were founded in bigotry. These provisions

therefore perpetuate the very abuses the Fourteenth

Amendment prohibits. And the Framers considered

the jury trial right an important right that must be

fully protected against state abuse. As Representative

Bingham said: before the Fourteenth Amendment,

States “denied trial by jury,” but once it passed, the

88 Id. at 5.

89 Id. (quoting Jury Reform Up to Voters, MORNING OREGONIAN

(Dec. 11, 1933) (quotation marks omitted).

90 Id. (quoting Debauchery of Boston Juries, MORNING

OREGONIAN (Nov. 3, 1933) (quotation marks omitted).

93 Id. (quoting One Juror Against Eleven, MORNING OREGONIAN

(Nov. 25, 1933) (quotation marks omitted).

Constitution would “provide against all such abuses

and denials of right.”92

When presented with a case that raises the issue,

the Court should revisit Apodaca and incorporate the

Sixth Amendment’s unanimity requirement.

29

92 Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st sess.

(statement of Rep. John Bingham).

app’x. at 85 (1871)

30

CONCLUSION

150 years ago, when the Fourteenth Amendment

was ratified, our Nation made its most significant

step towards fulfilling the equality promised by the

Declaration of Independence. The Fourteenth

Amendment ensured that all citizens—Black and

white—were guaranteed the rights embodied in the

Constitution and provided protections should States

try to deprive citizens of their rights. In accord with

the Fourteenth Amendment’s purpose and the intent

of its Framers, the Court should hold that the

Fourteenth Amendment incorporates the Eighth

Amendment’s Excessive Fines Clause.

Respectfully submitted,

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

Director-Counsel

Janai S. Nelson

Samuel Spital

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

40 Rector Street,

5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

September 11, 2018

Daniel S. Harawa*

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

700 14th St. NW

Suite 600

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

dharawa@naacpldf.org

Counsel for Amicus

Curiae

* Counsel of Record

mailto:dharawa@naacpldf.org