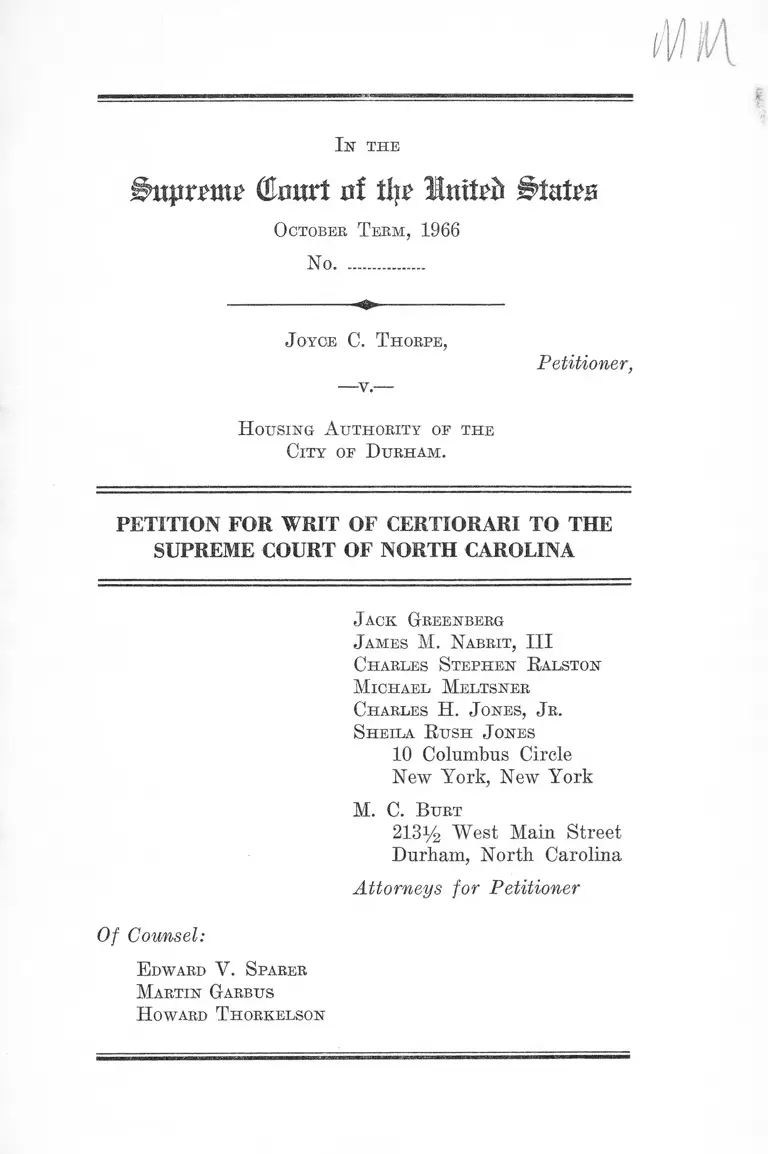

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1966. f52d5629-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e079bd7-8742-4f84-b260-1b3119ca0589/thorpe-v-housing-authority-of-the-city-of-durham-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

(£mtt ni % Inttpft §>UUb

October T erm, 1966

No.................

J oyce C. T horpe,

— v.—

Petitioner,

H ousing A uthority of the

City of Durham.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen R alston

Michael Meltsner

Charles H. J ones, J r.

Sheila R ush J ones

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

M. C. B urt

213% West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

E dward Y. Sparer

Martin Garbus

H oward T horkelson

I N D E X

Opinions B elow ................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 1

Question Presented......................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Statement ........................................................................... 3

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below.............................................................................. 6

R easons poe Granting the W rit

The Question of the Right of Tenants of Public

Housing to a Fair Hearing on the Reasons for

Eviction Is of National Importance ........................ 7

Conflict Between the Decisions of This Court and

a Judgment Below as to the Right to a Hearing

Necessitates Resolution of the Issue by This Court 14

Conclusion................................................................................. 20

A ppendix I ......................................................................... la

■M.

A ppendix II ......................................................................... 5 a

A ppendix III ..................................................................... 11a

PAGE

11

Table of Cases

Brand v. Chicago Housing Authority, 120 F. 2d 786

(7th Cir. 1941) .......................................................... 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .............. 7

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 .................................................................................. 16

Chicago Housing Authority v. Blackman, 4 111. 2d 319,

122 N. E . 2d 522 (1954) ............................................ 19

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S. 278 .... 17

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F. 2d 180

(6th Cir. 1955) ................................................. 16

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F. 2d

150 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied, 368 U. S. 930 .......15,17

Frost Trucking Co. v. R. R. Com., 271 IT. S. 583 ........... 17

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 IT. S. 335 ............................. 7

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U. :S. 474 ................................. 14

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U. S. 12 ......................................... 7

Holt v. Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Au

thority (E. D. Va., C. A. No. 4746, Sept. 7, 1966) .... 19

Housing Authority of Los Angeles v. Cordova, 130

Cal. App. 2d 883, 279 P. 2d 215 (App. Dept., Superior

Ct., 1955) ................................................................. 19

Housing Authority of City of Pittsburgh v. Turner,

201 Pa. Super. 62, 191 A. 2d 869 (Superior Ct. Pa.

1963) .............................................................................. 19

PAGE

Interstate Commerce Commission v. Louisville and

N. R. Co., 227 U. S. 8 8 ................................................ 15

Ill

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341

U. S. 123.......................................................................14,18

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp.

174 (M. D. Tenn. 1961) ................................................ 15

Kutcher v. Housing Authority of Newark, 20 N. J. 181,

119 A. 2d 1 (1955) ........................................................ 19

Kwong Hai Chew v. Golding, 344 U. S. 590 .................. 16

Lawson v. Housing Authority of City of Milwaukee,

270 Wise. 269, 70 N. W. 2d 605 (1955), cert, denied,

350 H. S. 882 (1955) .................................................... 19

Rudder v. United States, 226 F. 2d 51 (D. C. Cir.

1955) .............................................................................16,19

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 TJ. S. 232 .... 15

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 ..................................... 17

Sherbert v. Yerner, 374 U. S. 398 .................................. 17

Slochower v. Board of Education, 350 U. S. 551 ....... 14

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, 336 F. 2d 630 (6th

Cir. 1964) ....................................................................... 16

Southern Railroad Co. v. Virginia ex rel. Shirley, 290

U. S. 190 ....................................................................... 15

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U. S. 488 .................................. 17

United States ex rel. Knauff v. Shaughnessy, 338 U. S.

537 .................................................................................. 16

PAGE

Walton v. City of Phoenix, 69 Ariz. 26, 208 P. 2d 309

(1949) ............................................................................ 19

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. !S. 183 ................... .......... 17

Williams v. City of Ypsilanti (D. Mich., C. A. No.

28936) .......................................................................... 19

Woods v. Wright, 334 F. 2d 369 (5th Cir. 1964) ....... 15

F ederal Statutes and R egulations

28 U. S. C. §1257(3) ................. 2

42 U. S. C. §1401 ............. ...........................................2,10,12

42 U. S. C. §1402 ............................................................10,13

42 IT. S. C. -§1409 ................................................................ 12

42 U. S. C. §1410 ................................. .......................... 12

42 U. S. C. §1411 ............................................................ 12,18

42 U. S. C. §1411e ............................................................ 18

42 IT. S. C. §1415......................... ..................................... 10

The Criminal Justice Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 552, 18

U. S. C. §3006A ........................................................ . 7

The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 508 .... 7

United States Housing Act of 1937 ............................. 10,12

Public Housing Administration, Consolidated Annual

Contributions Contract, Part I, Sec. 206, Admission

Policies, PHA 3010, p. 8 ............................................ 12

State Statutes and R egulations

Chap. 157, Art. 1, Gen. Stat. of North Carolina ....2, 3,10

§157-2, Gen. Stat. of North Carolina ......................... 10

iv

PAGE

V

§157-4, Gen. iStat. of North Carolina............................. 10

§157-9, Gen. Stat. of North Carolina ......................3,10,12

New York Housing Authority Regulations, 9N1287,

§la(7) ............................................................................ 11

PAGE

Other A uthorities

Bibliography of Selected Readings in Law and Poverty,

in Conference Proceedings, National Conference on

Law and Poverty (1965) ............................................ 8

Conference Proceedings, The Extension of Legal Ser

vices to the Poor (1964) ............................................ 8

Friedman, Public Housing and the Poor: An Over

view, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 642 (1966) ............................. 10

Handler, Controlling Official Behavior m Welfare Ad

ministration, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 479 (1966) .................. 8

Harvith, The Constitutionality of Residence Tests for

General and Categorical Assistance Programs, 54

Calif. L. Rev. 567 (1966) ............................................ 9

O’Neil, Unconstitutional Conditions: Welfare Benefits

with Strings Attached, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 443 (1966) .. 9

Poverty, Civil Liberties, and Civil Rights: A Sympo

sium, 41 New York U. L. Rev. 328 (1966) .............. 8

Property Rights and the Low-Income Tenant: Law

as an Instrument of Social Reconstruction. Institute

for Policy Studies (mimeo) July, 1966 ............... ...... 11

Reich, Individual Rights and Social Welfare: The

Emerging Legal Issues, 74 Yale L. J. 1245 (1965) .... 8

VI

Reich, The New Property, 73 Yale L. J. 733 (1964) .....8,16

Schorr, How the Poor Are Housed, p. 215 “Poverty in

America,” University of Michigan Press .................. 13

Seavey, Dismissal of Students: “Due Process,” 70

Harv. L. Rev. 1406 (1957) ........................................ 16

Symposium: Law of the Poor, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 319

(1966) ............................. .............................................. 8

PAGE

I n t h e

Bupxmx (£mxt iif % Itttfrft States

October Term, 1966

No.................

J oyce C. T horpe,

—v.—

Petitioner,

H ousing A uthority of the

City of Durham.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina en

tered in the above case on May 25, 1966.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina is

reported at 148 S. E. 2d 290 (1966) and is set forth in Ap

pendix A, infra, pp. la-4a. The findings of fact and conclu

sions of law of the Superior Court of Durham County are

unreported and are set forth in Appendix B, infra, pp.

5a-10a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

was entered on May 25, 1966. The time for filing this peti

tion for writ of certiorari was extended by Mr. Justice

2

Brennan to and including October 21, 1966. The jurisdic

tion of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1257

(3), petitioner having asserted below and asserting here

deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution and stat

utes of the United States.

Question Presented

Petitioner, a Negro, and her children have been tenants

in a low-income housing project constructed with Federal

funds and administered by an agency of the State of North

Carolina pursuant to Federal regulations. The day after

petitioner was elected as an official in a tenant’s organiza

tion, the Housing Authority informed her that it was termi

nating her lease.

Was petitioner denied rights guaranteed by the due proc

ess clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the First and

Fifth Amendments of the Constitution of the United States

by the public housing authority’s refusal to accord her a

hearing on the reasons for the eviction?

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

This petition involves the First, Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

This petition also involves sections of the United States

Housing Act, as amended, 42 U. S. C. §§1401 et seq. and

portions of the North Carolina Housing Authorities Act,

Chapter 157, General Statutes of North Carolina. These

provisions are set forth in Appendix C, infra, pp. lla-30a.

3

Statement

Since November 11,1964, petitioner and her children have

been tenants in MeDougald Terrace, a public low-rent hous

ing project owned and operated by the Housing Authority

of the City of Durham, North Carolina, under authority of

state law and pursuant to a contract with the Federal Gov

ernment (R. 12).1

Under North Carolina law the Housing Authority is a

“ public body and a body corporate and politic, exercising

public powers” (§157-9, Gen. Stat. of North Carolina) and

has “ all the powers necessary or convenient to carry out

and effectuate the purposes and provisions” (Ibid.) of the

North Carolina Housing Authorities Law (Chapter 157,

Article 1, Gen. Stat. of North Carolina). The Authority

also has power “to manage as agent of any city or munici

pality located in whole or in part within its boundaries any

housing project constructed or owned by such city,” and

“ to act as agent for the federal government in connection

with the acquisition, construction, operation and/or man

agement of a housing project” (§157-9, Gen. Stat. of North

Carolina) (R. 12).

Petitioner has occupied the project under a lease agree

ment (E. 18-25), whose initial term was f rom November 11

to November 30, 1964, and which provided that it would

thereafter be automatically renewed for successive terms

of one month each (R. 18). On August 10, 1965, petitioner

was elected president of the Parents’ Club, a group com

posed of tenants of the project (E. 13). The following day,

_ 1 Following the judgment of the trial court below they have con

tinued to remain in the premises under stays of the eviction order

pending appeal.

4

August 11,1965, petitioner was notified that her lease would

be cancelled effective August 31, 1965, at which time she

would have to vacate the premises (R. 25), The Authority

gave no reason for the eviction but merely cited the pro

vision of the lease (R. 19) that permitted the landlord to

cancel upon fifteen days notice (R. 25). Although petitioner

requested a hearing to go into the reasons for her eviction,

the request was denied (R. 5-6).

There was no provision in the lease which specifically

either granted or denied the Authority the right to evict

without cause and hearing. The lease did provide, however,

that either party could terminate by giving written notice

of such termination fifteen days prior to the last day of

the term (R. 19). This provision was construed by the

Authority to permit eviction without cause and without a

hearing. The lease, prepared by the Housing Authority,

further provided that the tenant could be evicted under

certain circumstances, including: non-payment of rent (R.

20); exceeding limits on family size or income (R. 22-23);

misrepresentations of material facts in the tenant’s ap

plication (R. 23); and membership in “an organization

designated by the Attorney General of the United States as

subversive” (R. 24).

On September 18, 1965, the Housing Authority instituted

an action of ejectment against petitioner and her three

children. The Justice of the Peace Court in Durham Town

ship, on September 20, 1965, ordered defendant and her

children evicted from the project upon a showing that the

notice of eviction was duly served (R. 8-11). Petitioner ap

pealed to the Superior Court of Durham County where

additional evidence was taken in the form of stipulated

testimony (R. 11-14).

5

Petitioner alleged that the ground for her removal was

her involvement with the tenants’ organizing group (R. 15).

The Authority denied this was the reason, but admitted

refusing her a hearing prior to the institution of litigation.

The Authority offered no proof concerning the reasons for

the removal of petitioner and her children and did not ex

plain why the notice to evict was sent out the day after

petitioner was elected president of the tenants’ group (R.

13-14). On the basis of the stipulations the Superior Court

found that the reason for the eviction was not petitioner’s

activities with the organizing group. The Court went on

to find that the Housing Authority had not given her

a hearing or a reason for the eviction (R. 5-6),2 and con

cluded as a matter of law that the Authority had no duty

to give petitioner a hearing or to communicate its reason

for terminating the lease; it affirmed the eviction.

Petitioner appealed to the Supreme Court of North Caro

lina, and on May 25, 1966, that Court affirmed the order

to evict. The Supreme Court held that the Authority was

under no obligation to conduct a hearing or advise the ten

ant of its reasons for terminating the lease, since its obliga

tions to its tenants were the same as the obligations of a

private landlord to its tenants. The Court cited as author

ity a 1913 North Carolina decision construing a lease in a

suit brought by a private landlord against his tenant for

loss of rents. A stay of the eviction order was granted by

the Supreme Court of North Carolina pending action by

this Court on a petition for writ of certiorari.

2 The relevant stipulations were that the Housing Authority gave

neither a hearing nor reason for the eviction (R. 12) ; that peti

tioner alleged that the reason for the eviction was her participation

in the organization of the Parents’ Club (R. 13); that the Director

of the Housing Authority would testify that whatever the reason,

if any, for the eviction it was not her activities in the tenants’

group; and that the court could make findings of fact based on

these stipulations and petitioner’s affidavit (R. 13-14).

6

How the Federal Questions Were

Raised and Decided Below

The question of whether the eviction without cause, ex

planation, or hearing, of petitioner and her children, ten

ants in a low-income housing project supported by federal

funds and administered by the Authority pursuant to fed

eral regulations, violated rights guaranteed to petitioner

and her children by the Federal Constitution and statutes,

was raised at the trials in the Justice of the Peace and

Superior Courts by affidavit and motion to quash the evic

tion proceeding (R. 14-18).:za

Following the entry of judgment by the Superior Court,

petitioner made exceptions to the court’s judgment (R. 28-

30), and gave notice of appeal (R. 31). Among the assign

ments of error argued to the North Carolina Supreme

Court was the following:

4. For that the Court erred in finding as a matter

of law that the Housing Authority of the City of Dur

ham did not owe duty to communicate or give the de

fendant any reason for its termination of her lease, nor

was it required or had any duty to hold a hearing on

said subject. As shown by E xception # 4 . (R. 32.)

In its opinion, the Supreme Court held that, “ It is imma

terial what may have been the reason for the lessor’s un

willingness to continue the relationship of landlord and

tenant after the expiration of the term as provided in the

lease.” 148 S. E. 2d 290, at 292 (App., p. 4a). In finding

2a The Motion to Quash stated, in part:

That the tenant in a Public Housing Project has a right to

her apartment and a deprivation of that right without a hear

ing violates due process of law as guaranteed by the 14th

Amendment (R. 17).

7

that the Authority was entitled to bring summary ejection

proceedings against petitioner without granting a hearing

or stating its reasons for eviction, the Supreme Court of

North Carolina necessarily rejected petitioner’s federal

claims.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Tlie Question of the Right of Tenants of Public Hous

ing to a Fair Hearing on the Reasons for Eviction Is of

National Importance.

Introductory

In recent years there has been a growing awareness of

and concern for the legal rights of the poor and the avail

ability of legal services necessary to preserve them. This

interest has been stimulated by decisions . of this Court,3

and has been furthered by Federal legislation,4 national

conferences,5 and, of course, the underlying economic and

social factors. The initial focus of this interest was on the

rights of criminally accused indigents. More recently, it

3 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Griffin v. Illinois,

351 U. S. 12; and Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335.

i E.g., The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 508, and

The Criminal Justice Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 552, 18 U. S. C. §3006A.

5 E.g., National Conference on Law and Poverty, Washington,

D. C., June 23-25, 1965, under the Co-Sponsorship of the Attorney

General and the Director of the Office of Economic Opportunity;

The Extension of Legal Services to the Poor, Washington, D. C.,

November 12, 13, 14, 1964, under the Sponsorship of the IJ. S.

Department of Health, Education and Welfare; National Confer

ence on Bail and Criminal Justice, Washington, D. C., May 27-29,

1964 under the Co-Sponsorship of the U. S. Department of Justice

and the Yera Foundation.

8

has shifted to encompass a variety of areas where legal

institutions—whether by omission or commission—discrimi

nate against the poor: landlord and tenant relationships,

consumer fraud, the relation of the indigent to state ad

ministration of public benefits, especially welfare and pub

lic housing, family problems, and the absence of legal ser

vices for poor clients. See, e.g., Symposium: Law of the

Poor, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 319-1014 (1966); Bibliography of

Selected Readings in Law and Poverty, in Conference Pro

ceedings, National Conference on Law and Poverty (1965)4

Conference Proceedings, The Extension of Legal Services

to the Poor (1964); Reich, Individual Plights and Social

Welfare: The Emerging Legal Issues, 74 Yale L. J. 1245

(1965); Poverty, Civil Liberties, and Civil Bights: A Sym

posium, 41 New York U. L. Rev. 328 (1966). One result of

this concern for the legal rights of the poor has been the

establishment of programs by both public and private or

ganizations to give substance and reality to those rights.6

Among the wide range of legal questions to which atten

tion is being given, one of the most important is that of

the right of indigent persons to public benefits. See Reich,

The New Property, 73 Yale L. J. 733 (1964); Reich, Indi

vidual Rights and Social Welfare: The Emerging Legal-

Issues, 74 Yale L. J. 1245 (1965); Handler, Controlling Offi

cial Behavior in Welfare Administration, 54 Calif. L. Rev.

6 Thus, under the Economic Opportunity Act the Federal Gov

ernment has begun to finance neighborhood legal offices devoted

exclusively to providing free legal advice to the poor. Similar

services are being provided by private organizations, such as

Mobilization for Youth in New York City, and the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. and the Center for Social

Welfare Policy and Law of Columbia University, on a nation-wide

scale. At the same time, organizations of the poor themselves have

arisen in various cities, e.g., the West Side Organization in Chicago,

and Rescuers from Poverty in Baltimore, Maryland.

9

479 (1966); Harvith, The Constitutionality of Residence

Tests for General and Categorical Assistance Programs,

54 Calif. L. Eev. 567 (1966). One of the key issues in the

right to public benefits is the one presented by the present

case, i.e., whether the recipients of such benefits can be

denied or deprived of them arbitrarily, or whether they are

entitled to procedural protections. See, e.g., O’Neill, Un

constitutional Conditions: Welfare Benefits with Strings

Attached, 54 Calif. L. Eev. 443, 474-478 (1966).

Thus, although this petition raises only a narrow question

of what has been called social welfare or poverty law, that

question is of substantial public importance since its reso

lution has ramifications affecting the rights of recipients

to all forms of welfare benefits. Moreover, even viewing

the case solely as affecting the rights of persons in public

housing, the issue is of great importance. According to

information supplied by the United States Department of

Housing and Urban Development, there are approximately

1,400 local housing authorities with low-rent projects

throughout the United States. These authorities have been

advised by the United States Public Housing Authority to

draw up their tenant leases on a month-to-month basis, and

it is the opinion of the Department that the local authori

ties “perhaps without exception, have followed this recom

mendation. This practice does permit evictions to be accom

plished after the giving of a notice to vacate which does not

state the reason therefor.” 7 Thus, the lease involved in

7 This information was supplied in a letter from Mr. Don Hum

mel, Assistant Secretary for Renewal and Housing Assistance,

Department of Housing and Urban Development, in response to an

inquiry from one of the attorneys for petitioner. The partial text

of the letter follows:

Concerning item 2, local authorities consistently have been

advised to draw their tenant leases on a month-to-month basis.

10

this case is substantially identical to that used by the hun

dreds of state and municipal housing authorities adminis

tering federally assisted low-income projects. See also,

Friedman, Public Housing and the Poor: An Overview,

54 Calif. L. Rev. 642, 659-661 (1966).

Thousands of persons reside in these low-income proj

ects, which generally provide the only decent housing avail

able to them because of their poverty.8 To the poor, there

fore, the terms of occupancy in these projects transcend

economic discrimination and involve basic notions of dignity

and responsibility in a free society:

The urban slum is one of the greatest social, political,

economic, and moral problems facing the United States.

It is our opinion that authorities, perhaps without exception,

have followed this recommendation. This practice does permit

evictions to be accomplished after the giving of a notice to

vacate which does not state the reason therefor. Local authori

ties recently, however, have been urged that, in a private con

ference, they should inform any tenants required to vacate of

the reasons for such action.

Formerly there was a federal requirement (called the “ Gwinn

Amendment” ) intended to exclude from tenancy in a low-rent

project any person who- was a member of an organization

designated as subversive by the Attorney General. This legis

lation expired approximately ten years ago. Any local author

ities which might now have a non-communist or similar oath

clause in their leases do so because of their own local policy

or possibly requirements of state law or simply because they

have neglected to delete from their lease forms obsolete pro

visions.

8 The United States Housing Act of 1937 and the North Carolina

Housing Authorities Act (see text and notes, infra), under which

the Housing Authority herein has been established and financed,

both make it clear that the expenditure of funds for publicly owned

housing is required because of the inability of the private sector to

provide decent, safe, and sanitary housing for low-income families.

42 U. S. C. §§1401, 1402; 1415(7) (App. pp. 11a, 12a, 18a-19a);

§§157-2, 157-4, 157-9, Gen. Stat. of North Carolina (App. pp. 20a,

21a-22a, 24a).

11

One major source of the problem is the lack of housing

units for low-income families and the inadequacy of

resources now devoted to building more. Another ag

gravating factor is the increasing separation of the

urban slumdweller from place of work or shopping

facilities which are moving out from the center of the

city. But there are important problems of the slum

that have little to do with the quality or location of

construction. They concern rather the legal and social

organization of slum living. The poor, whether in pub

lic or private housing do not share the same legal re

lations as the rest of the society. While the sanctity

and importance of the home is basic to the American

ideology and tradition, and important safeguards sur

rounding the home are written into the Constitution,

the poor frequently have no rights of decision over

where and under what conditions they live. On such

basic questions as length of tenancy, repairs, privacy,

admission or acceptance, it appears that there is one

law for the middle class and another for the poor. Eco

nomic discrimination is reflected not only in geographi

cal divisions, but in legal ones. Property Rights and

the Low-Income Tenant: Law as an Instrument of

Social Reconstruction. Institute for Policy Studies

(mimeo) July, 1966.

Since no other decent housing is available, an unbridled

power by housing authorities to evict without reason or

hearing is punishment of the severest kind, particularly

since some housing authorities have promulgated regula

tions preventing an individual from being considered as a

tenant after he has once been evicted from a project. (See,

e.g., New York Housing Authority Regulations, 9N1287,

§la(7).)

12

Indeed, the existence and exercise of such a power is in

conflict with the declared policy of the United States Hous

ing Act of 1937 (42 U. S. C. §§1401 et seq.) under which

the Housing Authority of Durham, and others throughout

the country, was financed (R. 12).9 The purpose of fed

erally supported low-income housing is set forth in 42

U. S. C. §1401 (App. p. 11a):

It is declared to be the policy of the United States

to promote the general welfare of the Nation by em

ploying its funds and credit, as provided in this chap

ter, to assist the several States and their political

subdivisions to alleviate present and recurring unem

ployment and to remedy the unsafe and insanitary

housing conditions and the acute shortage of decent,

9 Section 157-9, Gen. Stat. of North Carolina, establishes the

Housing Authority as a “public body and a body corporate and

politic, exercising public powers” necessary to carry out the pur

poses of the North Carolina Housing Authorities Law (Appendix,

pp. 24a, 25a). The Authority has power to manage any housing

project owned by the city and, “ to act as agent for the federal

government in connection with the acquisition, construction, opera

tion and/or management of a housing project or any part thereof.”

(§157-9, Gen. Stat. of North Carolina, App., p. 25a.) Having

received Federal financial support and operating pursuant to its

contract with the Federal Government (R. 12), the Authority must

adopt and promulgate regulations for internal management (such

as lease provisions) that are consistent with and reasonably related

to the purposes of low-income housing (42 U. S. C. §§1401, 1410

(g) (2) (App., pp. 11a, 17a) ; Public Housing Administration, Con

solidated Annual Contributions Contract, Part I, Sec. 206, Admis

sion Policies, PHA 3010, p. 8 (1964)). The Federal Act further

provides that the Federal Public Housing Administration dis

tributing the funds is authorized to lend all municipal Housing Au

thorities an amount not in excess of 90 percent of the final develop

ment cost of the project and also to make annual contributions over

a period of years. Congress then appropriates funds to implement

the contracts made by the federal agency and the tenants of the

project are selected by the municipal authority subject to the loan

or subsidy contract with the government. (42 U. S. C. §§1409, 1410

and 1411.)

13

safe, and sanitary dwellings for families of low in

come, in urban and rural nonfarm areas, that are in

jurious to the health, safety, and morals of the citizens

of the Nation. * * * It is the policy of the United

States to vest in the local public housing agencies the

maximum amount of responsibility in the administra

tion of the low-rent housing program, including re

sponsibility for the establishment of rents and eligi

bility requirements (subject to the approval of the

Authority), with due consideration to accomplishing

the objectives of this chapter while effecting economies.

Certainly, the absolute power conferred on the respon

dent Authority by the court below to evict without a hear

ing, and hence for no reason or at the unbridled whim of

housing officials, runs directly contrary to the purposes of

insuring low-income citizens a decent place to live and of

promoting stability and security in the poor families the

Act is intended to benefit. Cf., 42 U. S. C. §1402, App.,

p. 12a. (See, Schorr, How the Poor Are Housed, p. 215,

“ Poverty in America,” University of Michigan Press.)

For these reasons, the question presented by this case

is no less than whether thousands of persons are able to

live at a minimum level of comfort and decency without

being denied this right by arbitrary and unexplained ac

tions of public agencies. In addition, the broader question

is involved of the right of persons receiving any public

welfare benefits to at least a bare m inim-mu of procedural

protection before the very necessities for life are taken

from them.

14

Conflict Between the Decisions of This Court and the

Judgment Below as to the Right to a Hearing Necessi

tates Resolution of the Issue by This Court.

The decisions of this Court make it clear that the fed

eral and state governments may not act arbitrarily to deny

persons benefits. One obligation imposed upon govern

ment is that before it takes adverse action against persons

it must conform to certain requirements of due process,

the most basic of which is a hearing. In his concurring

opinion in Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. Mc

Grath, 341 U. S. 123, at 171, Mr. Justice Frankfurter de

scribed why the due process clause requires a hearing be

fore valuable rights are denied:

Man being what he is cannot safely be trusted with

complete immunity from outward responsibility in de

priving others of their rights . . . That a conclusion

satisfies one’s private conscience does not attest its

reliability . . . Secrecy is not congenial to truth-seeking

and self-righteousness gives too slender an assurance

of rightness.

In cases involving federal employment, even when na

tional security has been involved, this Court has held that

administrative action which denies governmental benefits

would be approved only when an opportunity to influence

the fact-finder and to explain adverse charges is accorded.

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U. S. 474. And, in Slochower v.

Board of Education, 350 U. S. 551, the Court reversed a

state administrative determination on Fourteenth Amend

ment grounds. Although the case is often considered with

respect to the assertion of the privilege against self

incrimination, the Court held that summary dismissal with

15

out any inquiry when the privilege was claimed was a

denial of due process:

This is not to say that Slochower has a constitu

tional right to be an associate professor of German

at Brooklyn College. The State has broad powers in

the selection and discharge of its employees, and it

may be that proper inquiry would show Slochower’s

continued employment to be inconsistent with a real

interest of the State. But there has been no such

inquiry here. We hold that the summary dismissal of

appellant violates due process of law. (350 U. S. at

559.)10

See also, Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U. S.

232. In closely analogous cases, involving the expulsion

of students from state colleges or high schools, lower fed

eral courts have applied the above principles and required

notice and a hearing. Dixon v. Alabama State Board of

Education, 294 F. 2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied, 368

IT. S. 930; Woods v. Wright, 334 F. 2d 369 (5th Cir. 1964) ;

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp. 174

10 Cf., Interstate Commerce Commission v. Louisville and N. B.

Co., 227 U. S. 88, 91. This Court, replying to the claim that a

Commission’s order made without substantial supporting evidence

was conclusive, declared:

. . . A finding without evidence is arbitrary and baseless.

And if the government’s contention is correct, it would mean

that the Commission had a power possessed by no other officer,

administrative body, or tribunal under our government. It

would mean that, where rights depended upon facts, the

Commission could disregard all rules of evidence and capri

ciously make findings by administrative fiat. Such authority,

however beneficently exercised in one ease, could be injuri

ously exerted in another, is inconsistent with rational justice,

and eomes under the Constitution’s condemnation of all arbi

trary exercise of power.

See also Southern Railroad Co. v. Virginia ex rel. Shirley, 290

U. S. 190.

16

(M. D. Tenn. 1961). See also eases collected in Reich,

The New Property, 73 Yale L. J. 733, 783-84 (1964), and

Seavey, Dismissal of Students: “Due Process,” 70 Harv.

L. Rev. 1406 (1957).11

The court below apparently based its holding on the con

cept that the Housing Authority of the City of Durham

has the same status as any private landlord. This posi

tion, however, is untenable, since it is clear that govern

ment is not immunized from constitutional requirements

because it occupies the relationship of landlord. See, Bur

ton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715;

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, 336 F. 2d 630 (6th Cir.

1964). As the Court of Appeals for the District of Co

lumbia has said:

The government as landlord is still the government.

It must not act arbitrarily, for, unlike private land

lords, it is subject to the requirements of due process

of law. Arbitrary action is not due process. Rudder

v. United States, 226 F. 2d 51, 53 (D. C. Cir. 1955).

Thus, for example, a public housing authority could not

discriminate on the basis of race. Detroit Housing Com

mission v. Lewis, 226 F. 2d 180 (6th Cir. 1955). Nor, it

seems, should it be differentiated from government acting

in other capacities. It apparently could not bar occupancy

11 Similarly, although the due process clause does not require

that an alien never admitted to this country be granted a hearing

before being excluded, United States ex ret. Knauff v. Shaughnessy,

338 U. S. 537, 542, once an alien has been admitted to lawful resi

dence in the United States and remains physically present here, it

has been held that “although Congress may prescribe conditions

for his expulsion and deportation, not even Congress may expel

him without allowing him a fair opportunity to be heard.” Kwong

Hai Chew v. Colding, 344 U. S. 590, 597-98.

17

for failure to take an oath, that was unconstitutionally

vague, Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S.

278, 288, or that barred membership in certain organiza

tions, Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183, 192. Govern

ment has been disabled from imposing a religious oath,

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U. S. 488; it has been forbidden

to condition the affording of benefits on performing acts

that violate one’s religious principles, Sherbert v. Verner,

374 U. S. 398; it has been prohibited from requiring a citi

zen to reveal all organizational affiliations, Shelton v.

Tucker, 364 U. S. 479.12 Yet, having been denied a hearing,

petitioner cannot tell whether she was evicted for reasons

that violate the holding of those cases.

The denial of the right to a hearing is even more

abhorrent when, as in this case, it raises questions of sup

pression of the right to speak and associate. Cf. Shelton

v. Tucker, supra. On the face of it, petitioner’s expulsion

following her election as president of a tenants’ associa

tion warranted exploration at a hearing on whether she

was expelled for that reason. Moreover, a provision in

12 Nor can the State successfully maintain the position that al

though the petitioner may have had a right to a hearing, she waived

that right by signing a lease with the provision involved herein

(R. 19). To require that petitioner insist that her lease specifically

contain a provision prohibiting her eviction without hearing or

cause if she wishes to retain her constitutional rights is to nullify

those rights themselves, especially where the State, as landlord,

has all of the bargaining power and the low-income individual, as

tenant, has none. A State may not exact the surrender of federal

constitutional rights as a price for the opportunity of living in a

public housing project or as an exchange for any benefit it has to

offer. See Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F. 2d

150, 156 (5th Cir. 1961), in which the Fifth Circuit held that a

state college could not require that students renounce the right to

due process upon expulsion as a condition to admittance; see also,

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479; Frost Trucking Co. v. B. B. Com.,

271 U. S. 583.

18

the lease barring tenants who belong to “ subversive or

ganizations” is patently unconstitutional.13 See, Joint

Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U. S.

123. There is no way of knowing, without a hearing,

whether false evidence was considered against this peti

tioner to the effect that she belonged to such an organiza

tion and that she was evicted for such a reason. She has

no knowledge of why she was evicted and has had no op

portunity to defend against such a false charge, if indeed

it was made. This contention is not entirely speculative

for it is not uncommon to charge subversive conduct to

persons engaged in protest movements of a totally legal

and constitutional nature.

Against the foregoing reasons for requiring an adequate

hearing and notice of reasons before eviction, the State

has proposed no countervailing interest. Certainly, a pub

lic housing authority may make regulations reasonably re

lated to the proper management of the projects under its

control. However, the rationality of such regulations must

be determined in relation to the purposes of the govern

mental activity involved.

An additional reason for review of the judgment of the

court below exists in that a number of state and federal

appellate courts have rendered conflicting decisions on the

question raised herein. Thus, in addition to the Supreme

Court of North Carolina in the present case, the Seventh

Circuit and courts in Arizona and Pennsylvania have held

13 It should be noted that the ostensible federal statutory author

ity for this lease provision, the so-called “ Gwinn Amendment”

(67 Stat. 307, 42 U. S. C. §1411c), expired more than ten years

ago. The continued inclusion of a prohibition against members of

such organizations raises serious questions as to the validity of the

entire lease.

19

that a governmental agency operating a housing project

may act like a private landlord and evict summarily under

the terms of a lease.14 On the other hand, the District of

Columbia Circuit, together with courts in New Jersey,

California, Wisconsin, and Illinois, have held that even

when acting as a landlord the government still must fol

low due process and hence cannot act arbitrarily.15 Be

cause of the seriousness and importance of the question

presented, it is imperative that this Court review the deci

sion below and resolve these conflicting decisions.

14 Brand v. Chicago Housing Authority, 120 F. 2d 786 (7th Cir.

1941) ; Walton v. City of Phoenix, 69 Ariz. 26, 208 P. 2d 309

(1949) ; Housing Authority of City of Pittsburgh v. Turner, 201

Pa. Super. 62, 191 A. 2d 869 (Superior Ct. Pa. 1963).

15 Rudder v. United States, 226 F. 2d 51 (D. C. Cir. 1955);

Kutcher v. Housing Authority of Newark, 20 N. J. 181, 119 A. 2d

1 (1955) ; Housing Authority of Los Angeles v. Cordova, 130 Cal.

App. 2d 883, 279 P. 2d 215 (App. Dept., Superior Ct. 1955) ;

Lawson v. Housing Authority of City of Milwaukee, 270 Wise.

269, 70 N. W. 2d 605 (1955), cert, denied, 350 U. S. 882 (1955) ;

Chicago Housing Authority v. Blackman, 4 111. 2d 319, 122 N. E.

2d 522 (1954). More recently, a district court has enjoined an

eviction on a finding that its reason was the activities of the tenant

in a tenant’s organization. Holt v. Richmond Redevelopment and

Housing Authority (E. D. Ya., C. A. No. 4746, Sept. 7, 1966). Anri

in Williams v. City of Ypsilanti (D. Mich., C. A. No. 28936), a

district court has issued a temporary restraining order barring a

Michigan housing authority from evicting the plaintiff under a

lease provision allowing termination if a woman who is the head

of a household has an additional child.

20

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, the petition for writ of cer

tiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

Charles S teph en R alston

M ic h ael M eltsner

C harles H . J ones, J r .

S h e ila R u sh J ones

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

M. C. B urt

213% "West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

E dward V . S parer

M artin G arbtjs

H oward T horkelson

A P P E N D I C E S

APPENDIX I

Judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

NORTH CAROLINA SUPREME COURT

S pring T erm 1966

No. 769—Durham

—-------------------------------------------------- .................................................... ............ ..........

H ousing A u th o rity of t h e C it y op D u r h a m ,

— v . —

J oyce C. T horpe .

Appeal by defendant from Bickett, J., October 1965 Civil

Session of Durham.

The plaintiff instituted summary ejectment proceedings

before H. L. Townsend, Justice of the Peace, to remove the

defendant from Apartment No. 38-0 Ridgeway Avenue,

McDougald Terrace, in the city of Durham. From a judg

ment in favor of the plaintiff in the Court of the Justice

of the Peace, the defendant appealed to the superior court

where the matter was heard de novo by the court without

a jury. The court made findings of fact, each of which is

supported by stipulations or by the evidence in the record.

The material facts so found may be summarized as follows:

The plaintiff, a corporation organized and operating

under the laws of the State of North Carolina, is the owner

of the tract of land known as the McDougald Terrace Hous

ing Project in the city of Durham, which includes Apart

ment No. 38-G Ridgeway Avenue. On 11 November 1964

2a

the plaintiff and the defendant entered into a lease con

tract whereby the plaintiff leased to the defendant the said

apartment for a term beginning 11 November 1964 and

terminating at midnight 30 November 1964. The lease pro

vided that it would be automatically renewed for successive

terms of one month each. It further provided that the lease

could be terminated by either party by giving to the other

written notice of such termination 15 days prior to the

last day of the term. There was no provision in the lease

requiring the lessor to give to the lessee any reason for

its decision to terminate the lease or requiring that any

hearing be held by the plaintiff, or by any other person

or agency, with respect to such decision.

The defendant occupied the apartment pursuant to the

lease. On 12 August 1965 the plaintiff gave, and the defen

dant received, a written notice that the lease was cancelled

effective 31 August 1965 and that at such time the plaintiff

would be required to vacate the premises. The plaintiff

gave no reason to the defendant for its decision to termi

nate the lease, advising the defendant that it was not re

quired to do so. The defendant requested a hearing but

the plaintiff did not conduct any hearing at which the de

fendant was present. Whatever may have been the plain

tiff’s reason for terminating the lease, it was neither that

the defendant had engaged in efforts to organize the ten

ants of McDougald Terrace nor that she was elected presi

dent of a group which was organized in McDougald Ter

race on 10 August 1965. The defendant refused to vacate

the premises.

Upon these findings, the court concluded that the plain

tiff terminated the lease as of 31 August 1965; that the

occupancy of the premises by the defendant after such

3a

date was wrongful and in violation of the plaintiff’s right

to possession; that there was no duty upon the plaintiff to

give to the defendant any reason for its termination of the

lease or to hold any hearing upon the matter; and that the

plaintiff was entitled to the possession of the premises and

the defendant was in wrongful possession thereof.

The court, therefore, gave judgment that the defendant

be removed from the premises, that the plaintiff be put in

possession thereof and that the plaintiff have and recover

from the defendant $58.00 plus a reasonable rent for the

premises from and after 1 November 1965 until the same

are vacated, together with the costs of the action. From

this judgment the defendant appeals.

M. 0. Burt, R. Michael F rank, Jack Greenberg, Sheila

R ush, E dward Y. Sparer of Counsel for defendant

appellant.

Daniel K. E dwards fo r plaintiff appellee.

P er Curiam. The plaintiff is the owner of the apartment

in question. The defendant has no right to occupy it except

insofar as such right is conferred upon her by the written

lease which she and the plaintiff signed. This lease was

terminated in accordance with its express provisions at

midnight 31 August 1965. With its termination, all right

of the defendant to occupy the plaintiff’s property ceased.

Since that date the defendant has been and is a trespasser

upon the plaintiff’s land.

The defendant having gone into possession as tenant of

the plaintiff, and having held over without the right to do

so after the termination of her tenancy, the plaintiff was

entitled to bring summary ejectment proceedings against

her to restore the plaintiff to the possession of that which

belongs to it. G.S. 42-26; Murrill v. Palmer, 164 NC 50,

80 SE 55. It is immaterial what may have been the reason

for the lessor’s unwillingness to continue the relationship

of landlord and tenant after the espiration of the term as

provided in the lease.

Having continued to occupy the property of the plaintiff

without right after 31 August 1965, the defendant, by rea

son of her continuing trespass, is liable to the plaintiff for

damages due to her wrongful retention of its property and

for the costs of the action. G.S. 42-32; McGuinn v. McLain,

225 NC 750, 36 SE 2d 377; Lee, North Carolina Law of

Landlord and Tenant, § 18.

No Error.

Moore, J., not sitting.

5a

APPENDIX II

Judgment of the Superior Court of Durham County

This cause, coming on to be heard, and being heard be

fore the undersigned, Honorable William Y. Bickett, Judge

Presiding at the October Civil Term of Durham County

Superior Court, upon plaintiff and defendant having ex

pressly waived trial by jury, and having stipulated and

agreed in open Court that this matter be heard without a

jury by the Judge, and that the Judge find the facts upon

stipulations made and affidavit filed, and render thereon

conclusions of law and judgment in the cause; and the

Court, after hearing argument of counsel and considering

and weighing the stipulations made in this action and the

affidavit filed therein, finds facts as follows:

(1) That the Housing Authority of the City of Durham

is and was during all of the times involved in this action,

and specifically on the 11th of November, 1964, and there

after to the present date, a corporation organized and

operating under and by virtue of the laws of the State of

North Carolina—specifically, the Statute known and desig

nated as the Housing Authorities Law of the State of

North Carolina;

(2) That during said times, C. S. Oldham was the Execu

tive Director of said Housing Authority of the City of

Durham and charged with responsibility for management

of the properties of the Housing Authority of the City of

Durham located in the City of Durham;

6a

(3) That on the 11th day of November, 1964, and there

after, continuously until this date, the Housing Authority

of the City of Durham was and is the owner of real prop

erty known as the McDougald Terrace Housing Project,

located in the City of Durham, and specifically a dwelling

apartment located in said housing project, designated and

known as No. 38-G Ridgeway Avenue;

(4) That on the 11th day of November, 1964, the plain

tiff and the defendant entered into and duly executed a

lease contract, wherein the Housing Authority of the City

of Durham leased to the defendant Apartment No. 38-G

Ridgeway Avenue in said McDougald Terrace Project for

the term beginning November 11, 1964, and terminating at

Midnight November 30, 1964, at a rental of $19.33 for said

term, payable in advance on the first day of said term; that

said lease contract further provided that the rental for

these premises would be based on the current family com

position and family income as were represented to the man

agement of the Housing Authority of the City of Durham,

and would be in conformance with the approved current

rent schedule which had been adopted by the Housing Au

thority of the City of Durham for the operation of the

project; that the lease further provided that the lease

would be automatically renewed for successive terms of one

month each at a rental of $29.00 a month, provided there

was no change in the income or composition of the family

and no violation of the terms of the lease; that the lease

further provided that the rent should be payable in advance

on the first day of each calendar month, and that the lease

could be terminated by the tenant by giving to the Housing

Authority of the City of Durham notice in writing of such

termination fifteen (15) days prior to the last day of the

7a

term, and that management could terminate the lease by-

giving to the tenant notice in writing of such termination

fifteen (15) days prior to the last day of the term; that

there was no provision in said lease whereby it was agreed

that the Housing Authority of the City of Durham would

give the defendant any reason for termination of said lease

or that any reason for the termination of said lease was

required, and there was no provision in said lease that

any hearing should be held by the Housing Authority or

any other agency or person with respect to any decision

by the Housing Authority of the City of Durham to termi

nate said lease and to give the defendant notice in writing

of such termination, as was provided in the language of

the lease;

(5) That the defendant, upon her execution of said lease,

entered into and occupied said Apartment No. 38-Gf Bidge-

way Avenue of the McDougald Terrace Project, owned by

the Plaintiff, Housing Authority of the City of Durham

and does now continue to occupy said dwelling apartment;

(6) That on the 12th day of August, 1965, the plaintiff,

Housing Authority of the City of Durham, gave to the

defendant, Joyce C. Thorpe, notice in writing as follows:

“Your Dwelling Lease provides that the Lease may be

cancelled upon fifteen (15) days’ written notice. This is

to notify you that your Dwelling Lease will be cancelled

effective August 31, 1965, at which time you will be re

quired to vacate the premises you now occupy” ; and that

the defendant duly received said notice to vacate on said

date;

(7) That the defendant failed and refused to vacate said

premises and continues to occupy same;

(8) That the Housing Authority of the City of Durham

duly brought an action in summary ejectment before the

Justice of the Peace Court in Durham County, and after

hearing before said Court judgment was duly entered, re

quiring the defendant Joyce C. Thorpe to vacate said prem

ises and ordering any duly constituted officer of Durham

County to remove the defendant from said premises;

(9) That the defendant gave notice of appeal to the

Superior Court and posted bond, pursuant to the provisions

of G. S. 42,-34;

(10) That the plaintiff Housing Authority of the City

of Durham, acting through C. S. Oldham, its Manager and

Executive Director, gave notice to the defendant to vacate

said premises not because she had engaged in efforts to or

ganize the tenants of McDougald Terrace, nor because she

was elected President of a group organized in McDougald

Terrace on August 10,1965; that these were not the reasons

said notice was given and eviction undertaken;

(11) That the plaintiff Housing Authority of the City

of Durham gave no reason to the defendant for giving her

notice that the lease was being terminated at the end of

the term, nor did the plaintiff or any of its agents or em

ployees conduct a hearing at which the defendant was pres

ent or invited to be present to inquire into reasons for

terminating her lease;

9a

(12) That the defendant did request a hearing on this

matter but had no hearing other than that before the Justice

of the Peace in this eviction action and in this Court;

(13) That the plaintiff, through its agents and employees,

did inform the defendant that the plaintiff was not required

to give or assign reasons to the defendant for the termi

nation of her lease, and has not given to her or communi

cated to her any reason for so doing, other than that they

desired to terminate her lease;

W herefore, the Court concludes, as a matter o f law, as

follows:

(1) That the defendant, during August of 1965, occupied

the premises owned by the plaintiff Housing Authority of

the City of Durham, known and designated as Apartment

No. 38-Gr Ridgeway Avenue, McDougald Terrace, under

and pursuant to the terms and provisions of a lease, where

by she was tenant from month to month;

(2) That by giving the defendant written notice of ter

mination of her lease on the 12th day of August, 1965, the

plaintiff effectively terminated the tenancy of the lease of

the defendant as of the 31st day of August, 1965;

(3) That the continued occupancy of said premises by

the defendant after the 31st day of August, 1965, was with

out right and was wrongful and against the express direc

tion of the owner of said premises to vacate and in violation

of said owner’s right to possession of said premises;

(4) That the Housing Authority of the City of Durham

did not owe a duty to communicate or give to the defendant

any reason for its termination of her lease, nor was it re

quired or had any duty to hold a hearing on said subject;

10a

(5) That the Housing Authority of the City of Durham

acted in conformity with and in accordance with the terms

and provisions of the lease entered into with the defendant,

and the provisions of the laws of the State of North Caro

lina, in terminating her lease;

(6) That the plaintiff is entitled to the possession of the

premises described hereinabove, and that the defendant

is in the wrongful possession thereof;

Now, THEREFORE, IT IS ORDERED, ADJUDGED AHD DECREED that

the defendant be removed from the said premises known

as Apartment No. 38-G Eidgeway Avenue, and the plain

tiff put in possession thereof, and that the plaintiff

have and recover from the defendant the sum of Fifty-

eight and No/100 ($58.00) Dollars, and a further amount,

if any, as reasonable rent for said premises from the 1st

day of November, 1965, until the premises are vacated by

the defendant, and the defendant shall pay the costs to be

taxed by the Clerk.

This 26th day of October, 1965.

W illiam Y. B ickett

Judge Presiding.

11a

APPENDIX III

Federal and State Public Housing Statutes

SELECTED PROVISIONS OF THE

UNITED STATES HOUSING ACT OP 1937

42 U.S.C. § 1401 et seq.

§ 1401. Declaration of policy

It is declared to be the policy of the United States to

promote the general welfare of the Nation by employing

its funds and credit, as provided in this chapter, to assist

the several States and their political subdivisions to alle

viate present and recurring unemployment and to remedy

the unsafe and insanitary housing conditions and the acute

shortage of decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings for families

of low income, in urban and rural nonfarm areas, that are

injurious to the health, safety, and morals of the citizens

of the Nation. In the development of low-rent housing it

shall be the policy of the United States to make adequate

provision for larger families and for families consisting

of elderly persons. It is the policy of the United States

to vest in the local public housing agencies the maximum

amount of responsibility in the administration of the low-

rent housing program, including responsibility for the

establishment of rents and eligibility requirements (subject

to the approval of the Authority), -with due consideration

to accomplishing the objectives of this chapter while effect

ing economies.

12a

§ 1402. Definitions

When used in this chapter—

Low-rent housing; eligibility; continued occupancy

(1) The term “ low-rent housing” means decent, safe, and

sanitary dwellings within the financial reach of families of

low income, and developed and administered to promote ser

viceability, efficiency, economy, and stability, and embraces

all necessary appurtenances thereto. The dwellings in low-

rent housing shall be available solely for families of low

income. Except as otherwise provided in section 1421b of

this title, income limits for occupancy and rents shall be

fixed by the public housing agency and approved by the

Administration after taking into consideration (A) the

family size, composition, age, physical handicaps, and other

factors which might affect the rent-paying ability of the

family, and (B) the economic factors which affect the finan

cial stability and solvency of the project.

(2) The term “ families of Ioav income” means families

(including elderly and displaced families) who are in the

lowest income group and who cannot afford to pay enough

to cause private enterprise in their locality or metropolitan

area to build an adequate supply of decent, safe, and sani

tary dwellings for their use. The term “ families” includes

families consisting of a single person in the case of elderly

families and displaced families, and includes the remaining

member of a tenant family. The term “ elderly families”

means families whose heads (or their spouses), or whose

sole members, have attained the age at which an individual

may elect to receive an old-age benefit under title II of

the Social Security Act, or are under a disability as defined

in section 423 of this Title, or are handicapped within the

13a

meaning of section 1701q of Title 12. The term “displaced

families” means families displaced by urban renewal or

other governmental action, or families whose present or

former dwellings are situated in areas determined by the

Small Business Administration, subsequent to April 1,1965,

to have been affected by a natural disaster, and which have

been extensively damaged or destroyed as the result of

such disaster.

Slum

(3) The term “ slum” means any area where dwellings

predominate which, by reason of dilapidation, overcrowd

ing, faulty arrangement or design, lack of ventilation, light

or sanitation facilities, or any combination of these factors,

are detrimental to safety, health, or morals.

Slum clearance

(4) The term “ slum clearance” means the demolition and

removal of buildings from any slum area.

Development; office space for renewal functions

(5) The term “development” means any or all undertak

ings necessary for planning, land acquisition, demolition,

construction, or equipment, in connection with a low-rent

housing project. The term “development cost” shall com

prise the costs incurred by a public housing agency in such

undertakings and their necessary financing (including the

payment of carrying charges, but not beyond the point of

physical completion), and in otherwise carrying out the

development of such project. Construction activity in con

nection with a low-rent housing project may be confined

to the reconstruction, remodeling, or repair of existing

buildings. In cases where the public housing agency is also

14a

the local public agency for the purposes of sections 1450-

1452, 1453-1455, 1456-1460, and 1462 of this title, or in

cases where the public housing agency and the local public

agency for purposes of such sections operate under a com

bined central administrative office staff, an administration

building included in a low-rent housing project to provide

central administrative office facilities may also include suf

ficient facilities for the administration of the functions of

such local public agency, and in such case, the Adminis

tration shall require that an economic rent shall be charged

for the facilities in such building which are used for the

administration of the functions of such local public agency

and shall be paid from funds derived from sources other

than the low-rent housing projects of such public housing

agency.

Administration

(6) The term “administration” means any or all under

takings necessary for management, operation, maintenance,

or financing, in connection with a low-rent-housing or slum-

clearance project, subsequent to physical completion.

Federal project

(7) The term “ Federal project” means any project owned

or administered by the Administration.

Acquisition cost

(8) The term “acquisition cost” means the amount pru

dently required to be expended by a public housing agency

in acquiring a low-rent-housing or slum-clearance project.

15a

Non-dwelling facilities

(9) The term “ non-dwelling facilities” shall include site

development, improvements and facilities located outside

building walls (including streets, sidewalks, and sanitary,

utility, and other facilities).

Going Federal rate

(10) The term “going Federal rate” means the annual

rate of interest (or, if there shall be two or more such

rates of interest, the highest thereof) specified in the most

recently issued bonds of the Federal Government having

a maturity of ten years or more, determined, in the case

of loans or annual contributions, respectively, at the date

of Presidential approval of the contract pursuant to which

such loans or contributions are made: Provided, That with

respect to any loans or annual contributions made pur

suant to a contract approved by the President after the

first annual rate has been specified as provided in this

proviso, the term “going Federal rate” means the annual

rate of interest which the Secretary of the Treasury shall

specify as applicable to the six-month period (beginning

with the six-month period ending December 31, 1953) dur

ing which the contract is approved by the President, which

applicable rate for each six-month period shall be deter

mined by the Secretary of the Treasury by estimating the

average yield to maturity, on the basis of daily closing

market bid quotations or prices during the month of May

or the month of November, as the case may be, next pre

ceding such six-month period, on all outstanding market

able obligations of the United States having a maturity

date of fifteen or more years from the first day of such

month of May or November, and by adjusting such esti

16a

mated average annual yield to the nearest one-eighth of

one per centum: And provided further, That for the pur

poses of this chapter, the going Federal rate shall be deemed

to be not less than 2y2 per centum.

Public housing agency

(11) The term “public housing agency” means any State,

county, municipality, or other governmental entity or pub

lic body (excluding the Administration), which is author

ized to engage in the development or administration of

low-rent housing or slum clearance. The Administration

shall enter into contracts for financial assistance with a

State or State agency where such State or State agency

makes application for such assistance for an eligible

project which, under the applicable laws of the State, is

to be developed and administered by such State or State

agency.

State

(12) The term “ State” includes the States of the Union,

the District of Columbia, and the Territories, dependencies,

and possessions of the United States.

Public Housing Administration

(13) The term “Administration” means the Public Hous

ing Administration.

Initiated

(14) The term “initiated” when used in reference to the

date on which a project was initiated refers to the date of

the first contract for financial assistance in respect to such

project entered into by the Administration and the public

housing agency.

17a

§ 1410. Annual contributions in assistance of low rent

als—Authorisation

Jf. .v."vv 'A'

Maximum income limits; admission policies

(g) Every contract for annual contributions for any low-

rent bousing project shall provide that—

(1) the maximum income limits fixed by the public

housing agency shall be subject to the prior approval

of the Administration and the Administration may re

quire the agency to review and revise such limits if

the Administration determines that changed conditions

in the locality make such revisions necessary in achiev

ing the purposes of the chapter;

(2) the public housing agency shall adopt and pro

mulgate regulations establishing admission policies

which shall give full consideration to its responsibility

for the rehousing of displaced families, to the appli

cant’s status as a serviceman or veteran or relation

ship to a serviceman or veteran or to a disabled

serviceman or veteran, and to the applicant’s age or

disability, housing conditions, urgency of housing need,

and source of income: Provided, That in establishing

such admission policies the public housing agency shall

accord to families of low income such priority over

single persons as it determines to be necessary to avoid

undue hardship; and

(3) the public housing agency shall determine, and

so certify to the Administration, that each family in

the project was admitted in accordance with duly

adopted regulations and approved income limits; and

18a

the public housing agency shall make periodic reexam

inations of the incomes of families living in the project

and shall require any family whose income has in

creased beyond the approved maximum income limits

for continued occupancy to move from the project un

less the public housing agency determines that, due

to special circumstances, the family is unable to find

decent, safe and sanitary housing within its financial

reach although making every reasonable effort to do

so, in which event such family may be permitted to

remain for the duration of such a situation if it pays

an increased rent consistent with such family’s in

creased income.

* -y. -V. -V- -V;W W W W

§ 1415. Preservation of low rents

# * # # #

Local responsibilities and determinations

(7) In recognition that there should be local determina

tion of the need for low-rent housing to meet needs not

being adequately met by private enterprise—

(a) The Administration shall not make any contract

with a public housing agency for preliminary loans

(all of which shall be repaid out of any moneys which

become available to such agency for the development

of the projects involved) for surveys and planning in

respect to any low-rent housing projects initiated after

March 1, 1949, (i) unless the governing body of the

locality involved has by resolution approved the ap

plication of the public housing agency for such pre

liminary loan; and (ii) unless the public housing

19a

agency has demonstrated to the satisfaction of the Ad

ministration that there is a need for such low-rent

housing which is not being met by private enterprise;

and

(b) The Administration shall not make any contract

for loans (other than preliminary loans) or for annual

contributions pursuant to this chapter with respect to

any low-rent housing project initiated after March 1,

1949, (i) unless the governing body of the locality in

volved has entered into an agreement with the public

housing agency providing for the local cooperation re-

quired by the Administration pursuant to this chapter;

(ii) unless the public housing agency has demonstrated

to the satisfaction of the Administration that a gap

of at least 20 per centum (except in the case of a dis

placed family or an elderly family) has been left be

tween the upper rental limits for admission to the

proposed low-rent housing and the lowest rents at

which private enterprise unaided by public subsidy is

providing (through new construction and available

existing structures) a substantial supply of decent,

safe, and sanitary housing toward meeting the need of

an adequate volume thereof; and (iii) unless the public

housing agency has demonstrated to the satisfaction

of the Administration that there is a feasible method

for the temporary relocation of the individuals and

families displaced from the project site, and that there

are or are being provided, in the project area or in

other areas not generally less desirable in regard to

public utilities and public and commercial facilities and