Landmark Job Bias Case Won by LDF

Press Release

March 10, 1971

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Landmark Job Bias Case Won by LDF, 1971. 2ae5946a-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e4626ba-7e93-4332-9dd7-9687db46dfe7/landmark-job-bias-case-won-by-ldf. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

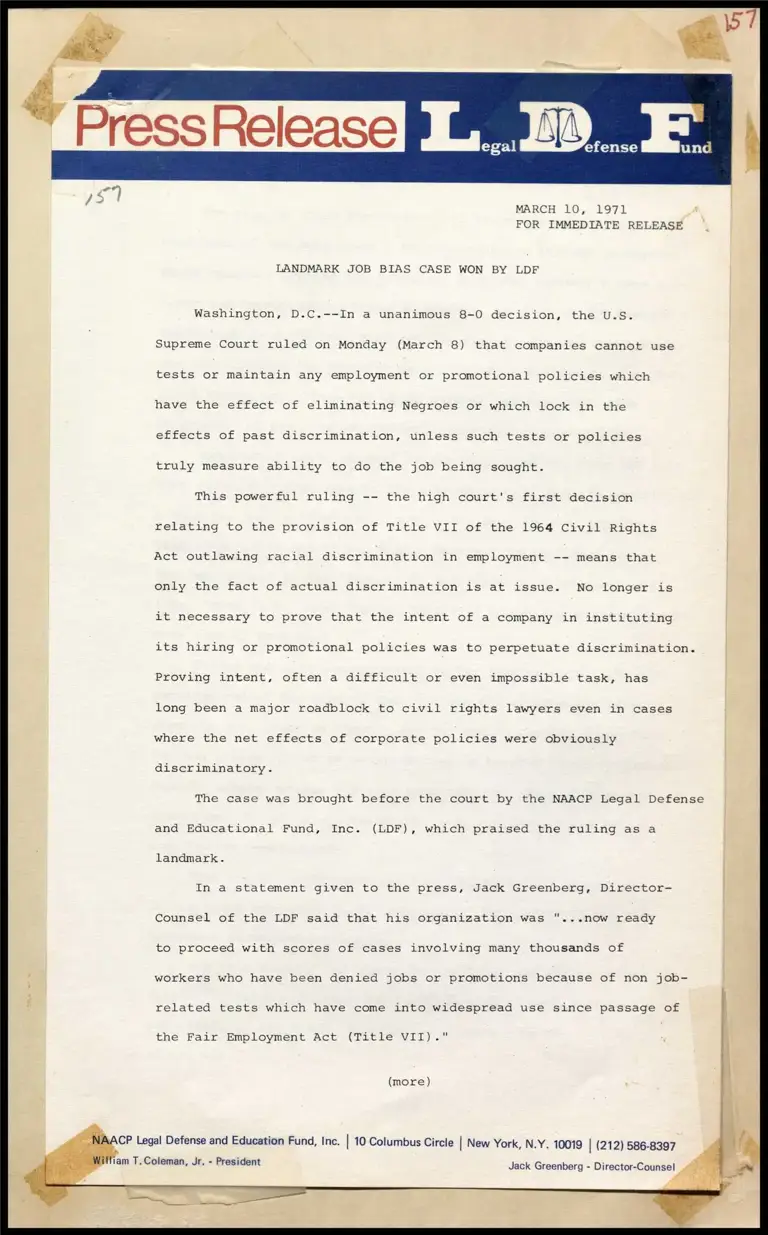

MARCH 10, 1971 :

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

LANDMARK JOB BIAS CASE WON BY LDF

Washington, D.C.--In a unanimous 8-0 decision, the U.S.

Supreme Court ruled on Monday (March 8) that companies cannot use

tests or maintain any employment or promotional policies which

have the effect of eliminating Negroes or which lock in the

effects of past discrimination, unless such tests or policies

truly measure ability to do the job being sought.

This powerful ruling -- the high court's first decision

relating to the provision of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act outlawing racial discrimination in employment -- means that

only the fact of actual discrimination is at issue. No longer is

it necessary to prove that the intent of a company in instituting

its hiring or promotional policies was to perpetuate discrimination.

Proving intent, often a difficult or even impossible task, has

long been a major roadblock to civil rights lawyers even in cases

where the net effects of corporate policies were obviously

discriminatory.

The case was brought before the court by the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF), which praised the ruling as a

landmark.

In a statement given to the press, Jack Greenberg, Director-

Counsel of the LDF said that his organization was "...now ready

to proceed with scores of cases involving many thousands of

workers who have been denied jobs or promotions because of non job-

related tests which have come into widespread use since passage of

the Fair Employment Act (Title VII)."

(more)

Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel

JOB BIAS CASE WON

PAGE 2

The case on which the decision is bas 1 arose when 13 black

employees of the Duke Power's Dan River Stream Station in Draper,

North Carolina applied for transfers from that company's sole all-

black and lowest-paying Labor Department, to jobs in the company's

traditionally white Coal Handling Department, one peg above Labor.

The applications for transfer were made after passage of the 1964

Civil Rights Act, Title VII which forbade job discrimination

on account of race, color, religion, national origin or sex.

Immediately after passage of the bill, however, Duke had laid

down additional requirements for transferring within its departments:

either you had to have a high school diploma, or else achieve a

passing score on one of two highly abstract intelligence tests --

the “Wonderlic" or the "Bennett." The tests included questions

like, "Does 'B.C.' mean ‘before Christ?'" and do "adopt" and “adapt"

have similar meanings?

During the case's progression to the Supreme Court, the LDF

received relief for some of the 13 black men seeking transfers

when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled that

the new policy placed an unfair burden on tenured black employees

because tenured whites had been permitted for years to transfer

throughout the plant without being subject to any of the new,

companywide requirements.

That ruling, unfortunately, provided no relief at all for

future black employees -- who would still be subject to the new

corporate promotional policies.

For this reason, LDF sought to challenge the whole concept of

corporate hiring and promotional policies which have evolved,

especially in the South, to evade compliance with the 1964 Civil

Rights Act.

(more)

JOB BIAS CASE WON

PAGE 3

In the Supreme Court LDF argued that the new requirements

for transferring within Duke had nothing to do with the ability

to do the jobs being sought and that the sole reason for their

existence was to exclude blacks from advancing within the

company. LDF pointed to the conditions under which most blacks

get their educations in the South, which makes it less likely for

black people than for whites to be able to satisfy such testing

and schooling requirements.

Accordingly, in its decision, the court noted that "the

objective of Congress in the enactment of Title VII is plain

It was to achieve equality of employment opportunities and remove

barriers that have operated in the past to favor an identifiable

group of white employees over other employees. Under the Act,

practices, procedures, or tests neutral on their face, and even

neutral in terms of intent, cannot be maintained if they operate

to 'freeze' the status quo of prior discriminatory employment

practices ... What is required by Congress is the removal of

artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers to employment when

the barriers operate invidiously to discriminate on the basis of

racial or other impermissible classification ... The Act proscribes

not only overt discrimination but also practices that are fair in

form, but discriminatory in operation ... What Congress has

commanded is that any tests used must measure the person for the

job and not the person in the abstract."

=30=—

For Further Information: Sandra O'Gorman

(212) 586-8397