Major v. Treen Post-Trial Memorandum in Support of Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law of Plaintiffs Barbara Major, et al. and in Response to Defendants Post-Trial Memorandum

Public Court Documents

June 9, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Major v. Treen Post-Trial Memorandum in Support of Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law of Plaintiffs Barbara Major, et al. and in Response to Defendants Post-Trial Memorandum, 1983. 3fe01b10-dd92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8fec3941-19ed-4acd-9d42-8938ae4b63d8/major-v-treen-post-trial-memorandum-in-support-of-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law-of-plaintiffs-barbara-major-et-al-and-in-response-to-defendants-post-trial-memorandum. Accessed January 28, 2026.

Copied!

I

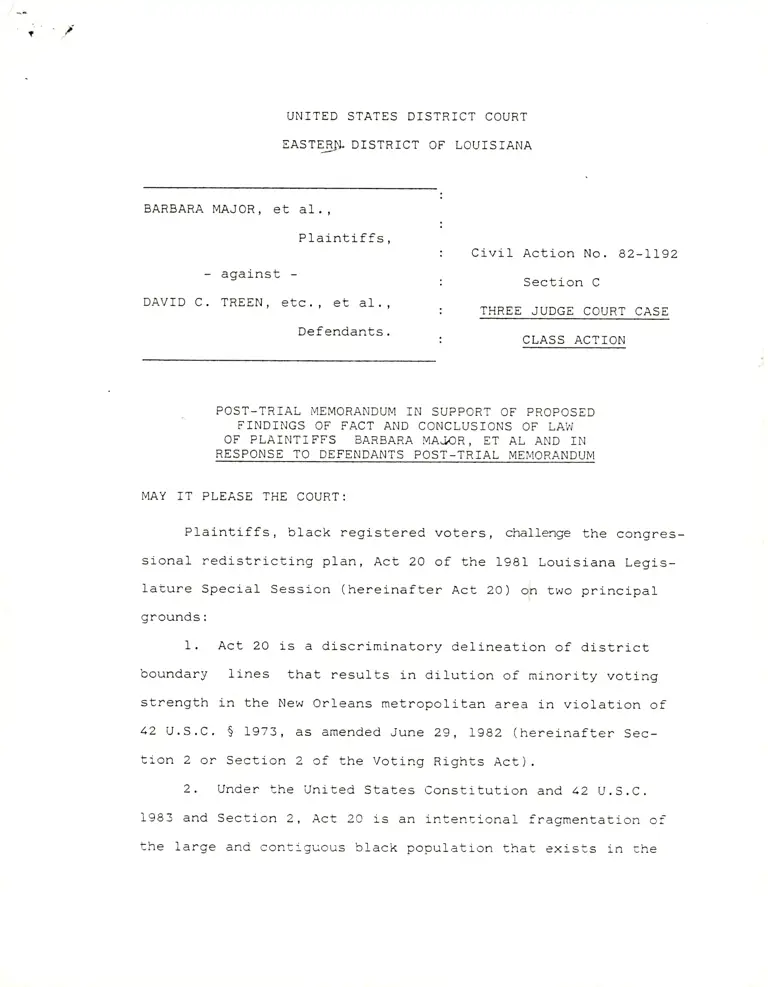

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTER}L DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

-

BARBARA MAJOR, et d1.,

Plaintiffs,

- against

DAVID C. TREEN, etc. , et df. ,

Defendants.

CLASS ACTION

POST-TR]AL MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PROPOSED

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

OF PLAINTIFFS BARBARA MA.IOR, ET AL AND IN

RESPONSE TO DEFENDANTS POST-TRIAL MEI4ORANDUM

MAY IT PLEASE THE COURT:

Plaintiffs, black registered voters, challenge the congres-

sional redistricting plan, Act 20 of the 1991 Louisiana Legis-

Iature Special Session (hereinafter Act 20) on two principal

grounds:

I. Act 20 is a dlscriminatory delineation of distrlct

boundary lines that results in dil-ution of minority voting

strength in the New orreans metropolitan area in violation of

42 U.S.C. $ 1973, as amended June 29, L9A2 (hereinafter Sec-

tion 2 or Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act).

2, Under the Unlted States Constitution and 12 U.S.C.

1983 and sectron 2, Act 2a is an intencionar fragmentation of

the large and contr-guous black population that exisis in rhe

CiviI Action No. 82-1192

Section C

THREE JUDGE COURT CASE

metropolitan New Orleans area, which splits that populatj_on

between two CongressionaL districts, in order to minimize the

possibility of electing a black person or a representative to

Congress chosen by the black voters in the Second Congressional

District.

Plaintiffs also maintain that Act 20 violates Section 2

and the United States Constitution because it perpetuates

historlcal discrimination against black voters by the State of

Louisiana.

I. STATEMENT OF FACTS

Reapporti.onment of Congress j-onal

Legislature is mandated by Article I,

Constitution and Art. fIf, S 1 of the

of L974,

distrj-cts by the Louisiana

$ Z of the Unlted States

Louisiana Constitution

Congressional districts were last reapportioned in L972.

As a result of the 1980 census, the State had to reapporti-on

its Congressional districts. The State of Louisiana has eight

Congressional distrlcts. The size of the ideal Congressional

district under the 1970 Census was 455,58O persons and under

the 1980 Census, the figure rose to 525,/*97 persons.

The Loulsiana Legi-slature recognized in early 1981 that

there was a need for Congressional reapportionment and began

L/

its proceedings to undertake this legisJ-ative responsibilityT

L/ Under state 1aw, legislative reapportionment is primarily

Ene obligation of the t ouisiana Legislature, but if ti.rat legi-l-

lative task is not completed by December 31, 1981, the last day

in the year after the latest federal decennial census, the ne-

apportionment obligation devolves to the Louisiana Supreme

Count. Louisiana Constitutlon, Art. IfI, S 6(B) .

-2

?/A. The Reapportionment Process

The formal reapportlonment process began in mid-July 1981

at the close of the regular 1981 legislative session with the

appointment of the members of the Congressional reapportion-

ment subcommittees in both houses of the legislature. No

blacks served as members of elther subcommlttee.

At the initial meetings of the Congressional reapportion-

ment subcomrnittees, held on July 23,1981, and August 21, 1981

rules for Congressional reapportionment were adopted, includ*

5/

lng a rule to avoid dilution of minority voting strength.

Hearings of the Congressional reapportionment subcom-

mittees were conducted from July through October 1981. Various

proposals were presented, including those of the Loulsiana

Congressional delegation and, on October 22, of Governor Treen.

The possibility of drawj-ng a majority black district based in

Orleans Parlsh was brought out "very early on in the public

hearings" and the legislative staff was "directed quite early

on to come up with such a proposal." Findings of Fact, para.

18.

?/ The process is described in greater detail in Plaintiffs'

Proposed Findings of Fact, paragraphs 14-51, and in P. Ex. /*98,

Robert Kwan's Section 5 Submission Analysis at 3-10.

3/ Dilution was frequently confused with the more narrow

Section 5 concept of retrogression. Nevertheless, at the

July 23 meeting, the members were also advised by staff

attorneys of the dangers of "discriminatorily artering access

to the voting process", of "carving up predominantly black

neighborhoods to make it impossibJ-e to elect a black." See

Finding of Fact, para . 17 .

-3

A11 of Governor Treen's three pnoposals, however, divided the

New orleans black populatlon concentration and none of covernor

Treen's plans contained a majority brack popuration distrlct.

Findings of Fact, para. 22. During this period the Governor

made known his opposi.tlon to congressionar reapportionment

prans containing majority black popuration districts. Findings

of Fact, paras . 22, 23 , 31.

on November 2, 1981, the First Extraordinary session of

the Louisiana Legisrature of r9g1 convened. Senate Bilr 5

(the Nunez Pran) was introduced in the Senate. The Nunez plan

provided for a Jefferson parish based di_strict (oistrlct r)

and an orleans Parish based district (oistrict 2), that was

54% brack ln population. The Nunez pran was a staff generated

pran which senator samuer B. Nunez, Jt". subsequentry adopted.

The plan was drafted to fo1low neutraL redistricting criteria

and to address issues that were raised at the public hearings.

Flndings of Fact, para , 26,

on the House side, Representative John w. Scott intro-

duced House Bill 2 (the Scott plan) which had a SO,2% bl_ack

majorlty population district in the second congressi.onal Dis-

trict. Both the Nunez pran and the Scott plan had majority

black districts and were the onry prans seriously considered

by the legislature prior to November 6.

By November 6, both houses of the legisrature had adopted

congresslonar reapportionment bilrs incorporating the Nunez

P1an, with a majority black population district in District 2.

Findlngs of Fact 27, 28 and 29. At this poi.nt, Governor Treen

issued a public statement that "any bill in that form is

unacceptable and without question wiIl be vetoed." The

Times-Picayune, November 7, 1981, p. 1. (P. Ex. 498 at 6);

Findings of Fact, para. 30. The threat of a veto kilIed the

Nunez Plan, and ellminated any opportunity for passing a plan

with a majority black congressional district. Findlngs of

Fact, paras. 35, 36. The Nunez Plan had passed both Houses

by a comfortable margin, but not by enough to override a

veto. No gubernatorial veto has ever been overridden by the

Louislana Legislature and the threat to veto was as powerful

an i.nstrument as actually vetoing the bill because the legis-

lature was concerned about enacting some form of reapportion-

ment within the Special Session. (Id.) See note I, at p. 2,

supra.

After news of the threatened veto reached the legisla-

ture, and in response to heavy lobbying by the Governor and

his aj-des, on November 9, the House reversed its earlier

position and adopted an amendment to incorporate the Governor's

Reconciliation Plan presented only hours earlier. Findings

of Fact, para. 37; P. Ex. 19E at 7, This action necessitated

appointment of a conference commlttee since the Senate re-

jected the new House amendments.

Appointment of the conference committee was delayed until

a compromlse acceptable to the Governor was reached in a

private session that took place in the sub-basement of the

State Capitol. The delay was necessary to avoid compliance

with the Louisiana Open Meetings Law, L.S.A.R.S. 42:2.1 et seq.

which requires notice and access to the public for formal

meetings. Findings of Fact, paras. 38, 39.

The actual work of hammering out a settlement took place

in a private meeti-ng in the Senate Computer Room ln the sub-

basement of the State Capitol. Findlngs of Fact, para. 39.

Although the group met for several hours wj-th participants

coming in and out, no black legislators were lnvited and no

nepresentatj.ves of the black community were consulted by any

of the people j-nvolved in negotiating a compromise pIan.

Representati-ves were present of a1l- interested parties, €X-

cept blacks. Findinqs of Fact, para. 39, 11. Blacks were

deliberately excluded from tne negotiations because, in light

of the Governor's position, the persons lnvolved in the private

meetings had no intenti-on of considering the interests of black

voters or of drawing a district that did not fragment the con-

centration of black voters in New Orleans. Findings of Fact,

para . 42, 49.

The guidelines followed in the sub-basement meeting were

to draw the Second Congressional Dlstrict with a population

majority in Jefferson Parish and with a black population that

was more than 40% buL less than 15% of the distri-ct. Find-

ings of Fact, para , /*O. The 45% black population ceiling was

dictated by the demographics of the area and the Governor's

position that a majority black dlstrict was unacceptable. (Id.)

Act 20 was drawn in the sub-basement meeting and was

approved by Governor Treen, who had stayed late at nj-ght to

-6

review it. Governor Treen had no concern, when he first re-

viewed Act 20, or at any time thereafter, that the Plan carved

up the black community 1n New Orleans wlthout regard to

political, historical or natural boundaries. Findings of Fact,

para , 1*3. After the Governor noted his approval- , a formal

conference committee was appointed on Wednesday, November I1.

No black Legislators were named to the conference cbmmittee.

Findings of Fact, para . /*4.

When the conference committee held its public meeting,

several black legislators delivered impassioned speeches

against the so-called compromise. Conference committee members

legislative staff and witnesses per'ceived the purpose and the

result of the new plan as the "(elimination of) the existence

of a black district from the plan." (P. Ex. 18 at 5, Scott,

Barringer). Representative Scott proposed amendments to add

back a majority black district based in New Orleans, but those

amendments were rejected. Findings of Fact, para. /*4.

On November 12, the last day of the special session, both

the full House and Senate passed the conference committee

plan. Governor Treen signed the bill into Iaw on November 19,

1981 as "Act 20 of the First Extraordinary Session of 1981. "

Discriminatory Results

1. Act 20 dilutes black voting strength in

the metropolitan Orleans area

Dilution of minority voting strength occurs where a re-

districting plan disperses a large, geographically insular

concentration of black voters into a number of dlstri-cts,

a

-7

submerging their voting strength in a racially polarized elec-

4/

torate.- (Vot. I , Tr. 1I1-114, Henderson) .

The evidence shows that in the City of New Orleans there

exj.sts the largest concentration of blacks living in the State of

Louisiana and in the New Orleans metropolitan area. According

to the 1980 census, the Parish of Orleans, coterminous with

the City, has a total population of 557,/*82 persons, of whom

55%, or 308,039, are black. Findings of Fact, para. 7, 8.

Act 20, unl-ike all of the congressional reapportionment

plans seriously considered by the legislature prior to the

Governor's threat to veto the Nunez PIan, as well as the plan

prepared by plaintiffs' expert Dr. Gordon Henderson, does not

respect the integrity of the Orleans Parish black concentra-

tion. Employing contorted 1ines, Act 2O divides the concentra-

tion into two Congressional Districts, so that black regi_stered

voters are a minority of the voters in each district . (SA,ly"

black voters are placed in the Second District; 21.5% black

voters are in the Flrst District). Findings of Fact, para. 9,

IO, 11. The lines of Act 20 are most contorted when they cut

through the heaviest black concentration in the Parish. The

/,/ This definition is simllar to one offered at their first

publj-c meeting to members of the congressional- neapportionment

cornmittee by an attorney for the Louisiana Legislature: "One

concern of the courts is the existence of a predominantly black

nelghborhood or area with a sufficient amount of population to

justify a district where it becomes apparent that the effect

was to carve up that group of people in such a way as to put

them in two or three separate districts and make it impossible

to elect a black representative." (P. Ex. 1 at 190).

-8 *o,iw

portion of the Second District that cuts into Orleans Parish

is shaped like a 12-sided drawing of the head of a duck

splitting majority black wards, and placing half the precincts

which are 95% or more black in population in each district.

Findi-ngs of Fact, para. 1O , 11 , 7l , 73; 77 .

The testi-mony at trial, and studies by experts for both

plaintiffs and defendants, shows that the electoral system in

the Orleans Parish metropolitan area is racially polarized.

Findings of Fact, para. 53. Plaintiffs' expert Dr. Henderson

conducted a specific computer-assisted analysis for elections

in this area from L976 to 1982 and found an extremely consis-

tent pattern of racia] bloc voting in all the elections ex-

amlned. Moreover, in 19 of 39 Parish elections, the correla-

tion coefficient between the race of the voter and the race of

the candldate was .9 or highdr. Fi-ndings of Fact, para. 54.

Even in those few electlons withln Orleans Parish in which

black candidates have been successful, there is st1II an ex-

tremely high leve1 of polarization along racial lines. The

1eve1 of polarization has increased over tlme, especially

when white voters perceive that a black candidate is credible.

(Morial deposition at 52-3)i Findings of Fact, para. 56.

Act 20 results in the dilution of the voting strength of

blacks in the metropolitan Orleans area because it disperses

the large black population concentration, submerging it in

two districts where the electorates are racially polarized.

In Iight of the hlgh level of polarizatj-on, black voters would

not have a faj-r chance of electing a congressional

-9

representative of their choice

59, 60.

Findings of Fact, para. 58,

2. Act 20 denles black voters an equal oppor-

tunity to participate in the political

process

In addition to dilution of the voting strength of btacks

in Orleans Parish, there are other indicla in the record of

the discriminatory results of Act 20.

(a) The State of Louisiana and every jurisdiction within

the state has a history of official discriminati_on against

blacks because of thej-r race. Discriminatory practices were

utilj.zed to disenfranchise blacks, to segregate blacks in

separate schools, and to separate physically blacks from whites

in public accommodations, churches and in "practically every

form of social contact between whites and blacks. " Findings

of Fact, paras. 64, 65, 66, 67 and 68. These discriminatory

policies and practices were only abandoned when enjoined by

the courts or made i1Iegal by federal civil rights legisration.

(fa.1 The hlstory of discrimination against blacks in

Louisiana has contemporary consequences that limit the ability

of and the opportunity for black voters to participate in the polj.tical

process. Act 20 builds upon these present effects of past

discrimination by fragmenting a sizeabre black poputation con-

centration and manipulating boundary lines in ways that submerge

black voting strength in a racially polarized electonate.

Findings of Fact, paras. 69, 70, 7L,

(b) The state has a majority vote requirement that en-

hances the opportunity for dlscrlmination against black voters

-10

as a result of their fragmentation into two congressionar dis-

tricts under Act 20. Findings of Fact 57 , 59.

(c) Blacks in Louisiana in general and Orleans parish

in particular bear the effects of discrimination in education,

employment and housing which hinder their ability to par-

ticipate effectively in the political process. The "hangover"

effect is evi-dent in a lower lever of education among blacks,

lower socio-economic status, poorer housing and less income

as reflected in 1980 census data. Findings of Fact, para. 66.

(d) No black has ever been elected to statewide office.

No black has been elected to the United States House of

Representatives from any of Louisiana's congressional districts

in this century. Although there are present-i-y 372 black elected

officials in Louisiana, this is less than 7% of the total

number of elected officiars in a state that is 29% bl-ack. The

large majority of black elected officials are eLected to minor

level offices and "the ovenwhelming preponderanc,e" of these

officials are erected from brack majority districts of 55-65%

black population.

In the City and Parlsh of New Orleans which are over 55%

black in population, less than 15% of the erected officiars

are black. In Jefferson, St. Bernard, St. Tamrnany and

Plaquemines Parishes, there are no brack officials elected at-

large where they had to run in a contested race against a

white opponent. Flndings of Fact, para 6; also Appendix A.

(e) The defendant's reasons for fragmenting the concen-

tration of brack voters in New orleans "'.. tenuous, conflict:-ng

- 11

and are not supported by the record. The defendants claim

that Act 20 simply continues an historical dlvision of Orleans

Parish into two congressionar districts. Defendants ignore

the fact that prior plans necessarlly divided the parish

because i.ts populatj.on was roughly equivalent to the popula-

tion of two ideal sized congressional districts. Findings of

Fact, para. 5. As of the 1980 census, that was no longer true.

rn fact, the population of orreans parish had diminished to

the point that it is now roughly equlvalent to the size of

only one ideal district. (Id.) Moreover, the sanctity of

historical boundary rines was wi11ingly violated in other

parts of the state, Findings of Fact, paras . 23, 24, 32, 43,

51, 52, and was embraced most tlghtry in orleans parish where

the bLack populati-on concentration had been fragmented. (rd. )

Defendants also argue that the dlvision und.er Act 20 of

bracks in orleans Parish is beneflcial to the black communi.ty.

This notion of "multi-representati-on" was not perceived as an

advantage by other parishes or by officials elected city-wide

in Orleans. Findings of Fact, paras , 20 , 32, 51 , and 52.

Furthermore, in enacting Act 20, other state poricies and

legisrativery adopted reapportionment criteria were violated

in the New orl-eans metropolitan area. rn the First and Second

congresslonar Districts under Act 20, at reast four state

pol-icies and reapportionment criter j.a were ignored: ( t ) Rct zo

does not create compact districts, (Z) Act 2O does not avoid

dilutlon of minority voting strength, (3) Act 20 does not re-

cqr]trze communities of interest and (4) Act zo crosses indis-

criminately tradltionaL political boundaries such as ivards and

-12

i

parish Iines. Findings of Fact paras

26, 61, 62, 63, 72 --73, 76, 77 .

Fina1ly, the protection of white

to dominate aI1 other considerations.

paras. 17 , 48, 78, 80.

. 10, L2, L7 , 19, Ig,

incumbents was al-lowed

Findings of Fact,

C. Discriminatory Intent

In Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corporation, 129 U,S, 252, 266-68 (telZ1, the

Supreme Court set out principles in determining whether an

illegitimate racial purpose exists behind state action. The

Supreme Court stated that a racially lnvidious motive may be

evidenced by a raclally disparate impact, or sometimes by a

clear pattern, unexplainable on other than racial grounds,

emerging from state action even though the actj_on appears

neutral on its face. The historical background of the decision

may also be an evidentlary source as well as the specific

seguence of events leading to the challenged decision. Further

evidence of such a racial purpose may be revealed by departures

from the normal procedural sequence or j-n a substantive manner,

dspecially if factors usually considered important by the

decisionmaker strongly favor a contrary decision.

In the I98I special legislative session, each house of

the Louisiana Legisrature finally passed the Nunez plan which

would have provided for an Orleans Parish based 54% bl-ack

population Congressional district, but that plan was never

enacted into 1aw. Findings of Fact,paras. Zg, 29, 35, 35, 36.

- 13

The record shows that the Nunez Plan would have been enacted,

but for Governor Treen's public threat of a veto. Findings

of Fact, paras. 30, 31, 35, 36, 37 ,

The sequence of events in the reapportionment process in-

dicate that the role of Governor Treen in the process was

cenbral in the reversal of the legislature from its adoption

of a plan which would incorporate a majority black Congressional

district. As he testified at trial, Governor Treen was not

open to any proposal that created a majority black Congressional

district, and refused to support any plan with more than /*4.7%

bLack populati-on in one district. Finding of Fact, paras, 22,

23, 31.

The Louisiana Legislative BIack Caucus consisting of the

two black senators and the ten black representatives unanimously

opposed Act 2O as a dilution of minority voting strength and

blame Governor Treen as the one chiefly responsible. See

remarks of Representatives Alphonse Jackson, Johnny Jackson,

Jr. and Diana Bajoie, Conference Committee hearing, November

1I, 1981, (P. Ex. 18), Findings of Fact, paras. 31, 5I.

Richard Turnley, Chain, Loui-siana Legislative Black Caucus

testified that the covernor was "opposed to having a district

that would be predominantely black, where the opportuni-ty

would be available for a black person to be e1ected." (Id.)

The analysis of Act 20 prepared by Department of Justice

attorney Robert Kwan (p. Ex. 49E) concludes that the Governor's

position was determinative:

-14

^rJ},|xx"d''

r#Ty*,

There is no question that Governor Treen

was heavlly involved in the Congressional re-

apportionment process and that his actions

determined the outcome of the process. Governor

Treen presented the legislature with three of

hls own reapportionment proposals and had his

aides actively promote those plans in the

Iegislature. He publicly threatened a veto of

the Nunez plan finally passed by both houses

of the legislature, whlch j_n the views of the

legislators, such as Senators Hudson and Nunez

and Representative Turnl_ey among others, was

the same as actually interposing the veto. His

aides aggressively lobbied the legislators dur-

ing the floor debates in the legislature and

signiflcantly over the weekend between the

adoption of the Nunez plan in the House and

that body's reversal on Monday. After that

weekend, Governor Treen proposed his so-call-ed

Reconclliation plan which the House adopted

hours 1ater, and his assent was required so

that a compromj_se could be reached on Congres-

sional reapportionment before the l9g1 special

session ended. In the views of the Louislana

Legislative Black Caucus, the submltted plan

is basically the Governor,s plan as modified.

ft is clear that the Governor was involved in

the process; to suggest otherwise would be as

one comrnenter ( sic ) said to argue that twoplus two is not four.

(P. Ex. 49E at 13)

The testimony at triaL reinforces the conclusion that the

Governor prayed a criticar role in the railroading of the Nunez

Plan and the enactment of a plan that divided through tortured

lines the concentration of brack voters in orreans parish.

Fi-ndingsof Fact, 35, 36, 37,38, 40, 46, 47; VoI. III, Tr. 94:

a. (Cassibry): This leglslature had done

it (tire textbook plan with a majority

black district), both sides overwhelm-

ingly , and then backed away?

A. (Baer): Yes, sir.

What does that te11 uS, any-

thing?

o.

1=

Yes, sir. It tells us that the

Governor still has a lot of

strength in this State.

Governor Treen has enunciated different reasons, depending

on the forum, for his opposition to the Nunez plan and in sup-

port of Act 20. Directly on the question of race and congres-

sionar reapportionment, Governor Treen testifled on cross-

examination that the idea of drawi.g u majority black dlstrict

based in orleans smacks of racism, is ominous, has no consti-

tutional or policy imperative, and that he was not open to any

proposar that created a majority black congressional district.

Findlngs of Fact 22, 31. on direct examination, however,

Governor Treen denied that the concentration of black voters

in the Second Congressional District under Nunez affected his

perception of the plan. (Vot. fV, Tr. 26),

rn his Section 5 submission to the Department of Justice,

(May 28, 1982 memorandum from speclal counsel- to the Govennor,

adopted by the Governor in his June 6, Lgg2 letter, D. Ex. 15;

see also P. Ex. /*9E at 15) the Governor took the position that

the Nunez Plan was simply an effort by the Louisiana Legislative

Black caucus to achieve proportional representation, guarantee-

i.ng the election of a black to congress. At trial , in response

to a question from the court, he denied, however, that Nunez

was ever considered by hlm "as assuring the election of a black

candidate in one congressional dJ-strict," (Vot. IV, Tr. gg)

or that the assurance of the election of a black was the thinking

or motivation of "proponents of the (Nunez) plan.,' (Id. )

A.

-16

Governor Treen testified at trial that he opposed the

Nunez Plan because it was an effort to undermine the power

base of Representative Robert Livingston, and that the pro-

tection of incumbents was a legitimate concern. (Vot. fV,

Tr. 75-76). Nowhere in his submission to the Department of

Justice does the Governor mention his concern for the protec-

tion of incumbents. (fA.; see D. Ex. 1, 15). Moreover, he

subsequently admitted on cross-examination that Represeptative

Livlngston would have had no trouble getting re-elected under

Nunez. (VoI. IV, Tr. 8S).

Some of his reasons for opposlng Nunez are internarly

inconsj-stent. The radical change in the First Distri_ct was

the reason the Governor gave on direct examination for his

opposition to Nunez. (rd.). yet, he also testified that one

of his goals was to change districts other than the First, to

make them more compact, (vo1. rv, Tr. 11, 17) and he was will-

ing to consider reshaping thelr configuration ,'in a more ac-

ceptable way." Findings of Fact, 32,

The Governor testified that orleans parish was better

served by having influence oven two representati-ves. yet,

he conceded that no other parish representatj-ve perceived

their interests best served by splitting the parish's influence

( Vot . IV, Tr. 13 ) , and in fact, ,'when a representative or

senator saw hls parish being.split he seemed to be in resistance

to that ..." (Id.).

Governor Treen testifled that an i-mportant redistricting

goal was not to disturb traditronar politicar 1ines. (vot.

-L7

IV, Tr. 5). Yet he expressed no concern about the way Act

20 tortured ward lines in the black community in New orreans,

and even with regard to white wards that were rerocated under

Act 20 from the second District ro the First, he dlsmissed

his concern about historlcal placement. (Vot. IV, Tr. 69).

None of the positi-ons vari-ousry advanced by the Governor

are supported by any credible evidence in the record. Far

from being an effort to maximize brack voting strength or to

unseat a particurar Representative, the Nunez plan was a text-

book plan drawn by the legislative staff in conformlty with

their trai.ning and with the congressional redistricting criteria

adopted by the joint committee. Findings of Fact, paras. 17,

18, 26, Nor was the Governor's notion of "multi-representation,'

embraced by officiaLs elected city wide in New orleans, Find-

i-ngs of Fact, paras. 20, 51, or supported by the shift in

population from orleans to Jefferson parish. rndeed, under

Act 20, orleans Parish dominates only one congressionirr Dis-

trict. Fi-ndings of Fact, paras. 5 , 63.

The Governor's position that bracks were better off in

two districts was at odds with every piece of evidence pne-

sented at the legislative hearings, and at trial, including

testimony by black politi-cal and civic readers, (LewJ-s, vo1.

f, Tr. 216-7, Turn1ey, Vo1. II, Tr. IO-12, MoriaI deposition

at 47-8, cassimene, vol. rr, Tr. r16) and the evidence inter

aria, of the high degree of raciar polarization in the erec-

torate. Findings of Fact, paras. 53, 54, 55, 56, 59, 60.

-18

The Governor consulted with no black people in reaching

his conclusions, (Vot. IV, Tr. l3-7/"), Findings of Fact, para.

51, and, contrary to his assertions before the Department of

Justice (O. Ex. 1, May 28 Memorandum at l-7), there was no input

from blacks in the confection of Act 20. Findings of Fact,

paras. 39, 41 , 42, 44, /*9 .

In 1960, the Governor was Chair of the Central Committee

of the States Rights Party of Louisiana. The main platform

of the Party was preservation of racial segregation and ne-

sistance to any federal effort to curtail segregatlon. Find-

ings of Fact, para . 67 . Whatever the primary impetus was for

his threat to veto a plan with a black population majority in

the Second Congressional District, in view of his black popula-

tion ceiling of 45% in one district and the opposition of

some legislators to a plan that would provide an opportunity

for a black to be elected to Congress (Flndings of Fact, para.

/.8), the Governor's threat to veto the Nunez Plan was a

vehicle for discrimination against black voters. Moreover,

the Governor's intervention at the point that the Nunez plan

had passed both houses of the legislature constituted a

departure from normal procedures. FinaIly, as a dj-rect result

of his veto threat, the legislature departed from criteria pre-

vlously adopted for reapportionment, delibenately excluded

black leglslators from the decision-making process, delayed

appointment of a fonmal conference committee to circumvent the

Louisiana open Meetings Law, and arlowed the interests of alr

- 19

other parties, except blacks, to dominate. When the conference

commi-ttee was finally appointed, parti-cipants, staff members

and witnesses, recognized that the purpose and result of the

new plan was to "e1j-minate the existence of a black district

f rom the pIan. " Findings of Fact, par'a . 44, The "specif ic

sequence of events leadi-ng up to the challenged decision, "

Arlington Heights, supra , 429 U.S. at 267 provides evidence

of an intent to discriminate.

An i-nference of intentional discrimination is reinforced

by other evidence in the record. The evj-dence showed unusual

5/

and tortured lines shaping the Second District,- Findlngs of

Fact, para. 10, 72,73,75, taking an especially sinuous path

through the concentration of black voters in New Orleans,

Findings of Fact, para. 9, 10, 11, 7L,73,77, and combining

extremel-y divergent communities of interest in one district,

Findings of Fact, paras. 12, 6f , 62. The evidence. i-s uncon-

tested that the Second Dlstrict 1s dominated by Jefferson

Parlsh, Findings of Fact, para. 63, and that this was inten-

tional. An inference can therefore be drawn that the resuLt-

ing submengence of the voting strength of black voters in the

Second District with the domination by predomlnantly

white Jefferson Parish was also intentional. Supporting this

inference is evidence of the racially polarized electorate,

5/ Even Mayor Monial found the sinuous course of the l1nes

confusing (Deposition at 38), and the Governor admitted that

under Act 20 i.n the First and Second Di-strict, "a1ot of

people don't know who their congressman or woman is now."

(Vot. fV, Tr. 69).

-20

the majority vote runoff requi-rement and the difficulty any

Second District representative would have representing equally

the concerns of the white Jefferson Parish voters and the

black voters in the Orleans Parish portion of the district.

The totallty of circumstances, including the deviations

from neutral crj.teria previously adopted, the railroading by

the Governor of a plan that recognized the concentration of

black voters 1n Orleans Parish and the substi-tution of a plan

that consciously minimized black voting strength, the exclu-

sion of blacks from the decision-making and especially from

the meetings before the formal meetings where the decisions

were being made, the preoccupation with protecting incumbents,

the unusual shape of the Ij-nes that fragrment the minority com-

munity, historical racial- discrimination and the absence of

a legitimate and consistently applied non-racial reason for

adoption of the plan at i-ssue mandates the conclusion that

Act 2O as it pertains to the First and Second Congressional

Districts has a discriminatory purpose j-n violation of the

United States Constitution and Section 2.

D. Preclearance

Act 20 is before this Court because the Assistant Attorney

General, United States Department of Justice faj-led to inter-

pose an objectlon pursuant to Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act. No evidence was presented that the Assistant Attorney

General, a politicaL appointee, nevlewed Act 20 and made his

decision in a manner that was reliable, trustworthy, or

-21

sufficiently adversarial to accord the conclusion of that pro-

cess any evidentiary weight. fn fact, the rebuttal evidence

of plaintiffs tends to show that the professional staff and

career experts in the Department investigated the facts and

reached the conclusion that Act 2O was lntentionally discrimin-

atory, that the Department's effort to investigate the facts

was thwarted when a routine request for more information was

reca11ed, that all references in the initial request to state-

ments made by the Governor regarding congressional reappor-

tionment were removed although the Governor's role in threaten-

ing to veto the Nunez Plan was obviously relevant, and that

the Department's consideration of the discrimiantory effects

of Act 20 was limited to an examination of retrogression, i:g.,

tvhether the percentage of blacks in Dlstrict 2 was reduced

from the level of black population under the 1972 Plan. The

decision of the Assistant Attorney General with regard to

Act 20 was the product of a non-adversary proceeding, was

inconsistent with the recommendations of his staff, and was

made in response to a concerted personal lobbyi-ng effort by

the Governor of Louisiana.

This conclusion was foreshadowed by the Louisiana Legls-

lative Council in a Memorandum, November 8, 1981, (p. Ex. 25

at 5), "a 44-46% black population district in a modj.fication

of one of the Governor's plans would Iikely neceive favorable

treatment 1n Reagan's Department of Justice." The June 18,

1982 decision of the Assistant Attorney General not to object

is not credible evidence of any of the relevant facts in

this case. Findi.ngs of Fact, para. 81.

aa

- L4

Defendants' Evidence

(I) Defendants attempted to rebut plaintiffs evidence

of the dllutlve results of Act 20 by showing that some bLacks

have been elected to publlc office in Orleans Parish and an

even smaller percentage have been elected to public offices

throughout the state (Compare Plaintiffs' Findings.of Fact,

Appendix A, Black Elected Officj-aIs in Louisiana); that some

white elected officials are responsive to black voters; that

a black could be elected under Act 20 in Distnict 2 because

of the presence of white cross-over voting in Orleans parish

and, based on population trends, a projection as to the growth

of minority population in the next ten years; and that blacks

are better off having influence in two districts.

Defendants' evidence of cross-over voting and popula-

tion projectlons are based on questionable methodology and even

more questionable expertise and should not be given any weight.

In partlcular the studies conducted and presented by defendants'

expert Kenneth serle were based upon projections from precincts

selected to produce the results sought. Furthermore, they are

irrelevant slnce the issue is (a) the result of Act 20 now,

not at some unspecified point in the future, and (b) the sub-

mergence of black voting strength in a Jefferson parish

domlnated district. The presence of some white cross-over

voting in New orreans is not evidence of white cross-over vot-

ing in Jefferson Parish. Defendants' expent John Wildgen

admitted that residents of the French Quarter and the Unlver-

sity District in Orleans Parish were the rpst likely to'bross-over"

E.

and vote for a black candidate. Those dlstricts are unique

to Orleans Parish. Findings of Fact, para. 55.

With regard to evidence of the number of black elected

officials, the evidence that no blacks have been elected

statewide or to Congress is most probatlve of this issue. A

reasonable comparison must be based on a juri-sdiction the

equivalent size of a Congresslonal district with a black

reglstration minority of 39%, and an electorate that is

racially polarized. Under this standard of comparison, the

evidence shows that the "extent to whi-ch members of the

minority group have been elected to public office" is de

mini-mus or ze"o.

Even if the Court chooses to consider evidence of blacks

elected to public office throughout the State of Louisiana,

the record shows that the "overwhelming preponderance" of

those office holders were elected from majority black dis-

tricts. Moreover, the vast dj-sparity even in Orleans Parish

between the number of black elected officials and the total

number of elected offi-cials shows that, even using the measure

most favorable to defendants, blacks in Louisj-ana do not

enjoy equal access to the politj-cal process.

Fina11y, defendants' evidence of responsiveness 1s only

relevant in rebuttal if plaintiff had chosen to offer evidence

of unresponsiveness. Here, plaintiffs did not attempt to

prove the unresponslveness of the incumbent congressional-

-24

representatives. Defendants' evidence of self-serving state-

-/'ments by elected politicians is not probative of the dis-

criminatory results of Act 20.

(2) Defendants attempt to rebut plaintiffs, evidence

of an intent to dlscriminate in the enactment of Act 20 by

relying on self-serving and inconsistent statements of the

Governor and other elected political figures. The incon-

sistency of these statements is itself evidence from which

an inference of intentional discrimination can be drawn. More-

over, in their post-trial memorandum, defendants concede many

of the facts on which plaintiffs re1y. They agree (Defendants

Memorandum at 8) that the creation of a majority black dls-

trict is an easy and proper solution if orleans parish is the

equivalent slze of one congressional district. The evidence

is undisputed that Orleans Parish is 1.06% the size of an

1dea1 district.

They agree that a majority black district based ln

orleans Parish was not onry an easy sorution, but a "socialIy

redeeming quality whi.ch well-intentioned people woul-d want for

District two." (fa. at 12) (emphasis added).

They concede that Governor Treen had a black popula-

tion ceiLing for the Second Di-strict. Under Act ZO, they

state, "District two ended up with /*4.5% black population,

only slightJ.y less than what the Governor intended.,'

(ra. at 14).

-25

(3) In their effort to rebut plaintiffs' evidence,

defendants rely on much that is outside the record, either

because 1t is speculative, (Defendants' Memorandum, at L7, 29,

42) inadmissible hearsay that was never properly authenticated

or even introduced into evidence (See lppendix A, B, C and D

to Defendants' Memorandum), by thelr own admission, rrot "directly

in evidence," (Defendants' Memorandum at 6-7, 10, 29) or

because it is contrary to the evidence that is in the record.

6/

(fa. at 16, 29, 37).

6/ For example defendants state at 16, "Chehardy says

politics, not the threat of a veto klIled Nunez." They cite

to the transcript of Mr. Chehardy's testimony, Vol. III, Tr.

23, where the wltness is assessing the relative significance

of the politics of Representative Llvingston and the racial

motivation of the leglslature as a whole. The cited portlon

of the transcrlpt contains no testimony by the witness com-

pari-ng politics to the threat of a veto, or anything else

that would support defendants' characterization. fndeed

the witness states to the conteary on that very page of the

transcript: "And when it became obvious that this plan was

not going to pass because of the veto threat, you know, that'

when the meeting took place in the basement and subsequent

thi.ngs happened." (Vot. fII, Tr. 23, Chehardy).

-26

II. LEGAL ARGUMENT

A. Act 20 1s a dlscrlmlnatory dellneatlon of congresslonal

boundary 11nes that results ln unlawful dllutlon of black vot-

1ng strength 1n the New Orleans metropolitan area 1n vlolatlon

of Section 2 of the Votlng Rlghbs Act.

The Voting Rlghts Act applies to clalms of dlscrlminatory

redlstrlctlng. Congress lntended the Voting Rlghts Act to be

a broad charter agalnsl all systems and practlces that dlmlnlsh

black votlng strength. When Congress extended the Voting Rights

Act in L975, the Senate observed:

As reglstratlon and votlng of mlnorily citlzens

lncreases, other measures may be resorted to

whlch dilute increaslng minorlty .rotlng strength.

Such measures may include the adoptlon of

dlscriminatory redistrlcblng plans .

s. Rep. No. 94-295,94rh Cong., lst Sess. L6-L7 Q975).

The Senate Report accompanying the L982 extension and

7/

amendment of the Act- echoes the same concern:

The initial effort -,.o i-mplement the Votlng Rlghts

Act focused on registratlon Ic ls not

surprlslng, therefore, that to many Amerlcans, the

Act 1s synonymous wlih achievlng mlnorlty reglstra-

t1on. But reglstratlon is only the flrst hurdle

to effectlve particlpation in the pofl .

the Act:

7/ S. Rep. No. 97-4L7, 97Lh cong., 2d Sess. (1982) (hereln-

after Senate Report). The Senate Report 1s reprlnted in the

Unlied Staies Code Cong. and Ad. News., No. 5, July L982, at

l-77 ff. The flrst E8 pages are the Report of the Committee on the

Judiclary and contaln ihe vlew of the co-sponsors of the amenci-

ments whlch passed the Senaie by a vote of 85 tc E. I28 Cong.

Bec. S. 7L39 (dally ed. June I8, 1982).

-)1 _

The rlght to vote can be

d1lut1on of votlng Power

an absolute prohlbltlon

baltot. Allen v. Bd. of

affected by

as well as

on castlng a

a

by

398Electlons,

u.s. 544,-5{9-CW9)

Senate Report, at 5 (emphasls added). Accordlngly:

IF]or purposes of Sectlon 2, the concluslon

. that I'there were no lnhlbltlons agalnst

Negroes becomlng candldates, and that ln fact

Negroes had reglstered and voted without

hlndrancert, would not be dlspositlve. Sectlon

2, as amended, adopts the functlonal vlew ofrrpollblcal processtt . rather than the

formallstlc vlew [T]hls section wlthout

questlon 1s almed at dlscrimlnatlon which

-!ak9s-

Senate Report, at 30 n. 120 (emphasls added).

Clalms of dlscrlmlnatory redlstrictlng fal1 squarely

wlthln the amblt of the Act. Indeed, "[T]he contlnulng problem

with reapportlonment 1s one of the major concerns of the Votlng

Rlghts Act " Senate Report, at 72 n. 31.

Sectlon 2 of the Votlng Rlghts Act spec1flcally pro-

hlblts redlstrlellng plans that result 1n dllution of mlnority

votlng strength. Sectlon 2 reaches any t'systems or practlces

whlch operate, deslgnedly or otherwlse, to mlnlmize or cancel

out the votlng strength and polltlcal effectlveness of mlnorlty

groups." S. Rep. No. 97-417, 971]n Cong., 2d Sess., at 28 (1982)

(herelnafter Senate Report. )

1. The Section 2 Standard

On June 29, L982, the Presldent slgned lnto Iaw an

.{.ci amendlng Seetj-on 2 to provide that votlng practlces are

unlawful whlch result i n che denlaL or abricigneni of ihe

right to vcte on acecuni oi race or cclor.

- 1J

Acl of June

B/

29,1982, 96 Stat. 13I.- Amended Sectlon 2, 42 U.S.C. $1923,

provldes:

(a) No votlng quallflcatlon or prerequlslte

to votlng or standard, practlce, or pro-

cedure shal1 be lmposed or applled by any

State or poIltleal subdlvlslon ln a manner

whlch results 1n a denlal or abrldgement

of the rlght of any cltlzen of the Unlted

States to vote on account of race or color,

or 1n contraventlon of the guarantees set

forth 1n Section 4(f)(2), as provided in

subsectlon (b ) .

A vlolatlon of subsectlon (a) 1s establlshed,

1f, based on the totality of clrcumstances,

lt ls shown that the poI1t1cal processes lead-

1ng to nominatlon or electlon in the state or

po1ltlcal subdivlslon are not equally open to

partlcipation by members of a class of citi--

zens protected by subsectlon (a) 1n that rts

members have less opportunity than other mem-

bers of the electorate to participate in the

po11t1ca1 process and to elect representatlves

of thelr cholce. The extent to which members

of a protected class have been elected to

offlce ln the State or po11t1ca1 subdlvlslon

1s one rrclrcumstanceil whleh may be considered,

provlded that nothl-ng 1n this sectlon establlshes

a rlghl to have members of a protected class

elected ln numbers equal to their proportlon

1n the populatlon.

(b)

As the leglslatlve history ln both houses makes cIear,

Sectlon 2 was amended primarlly in response to the declslon 1n the

City of Moblle v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), to provlde that

proof of dlserlmlnatory purpose 1s not required to establlsh a

9-_/ The House passed. 1ts verslon of a b111 amend.i-ng and extendlng

the Votlng Rlghts Act ot L965 on October 5, 1981. 127 Cong. Rec.

H. 7011. The Senate thereafter adopted lts version of the bill

on June 18, L982. L28 Cong. Rec.'S.7139. Subsequently, on june

23, L982, the House unanimousely adopted ihe final Senate verslon

of the.{ct wlth the undei'standing that the effect of the Sectlon

2 amendment was identlcal under elther. the ori-glna1 liouse b1I1

or the Senate biIl. L28 Cong. Rec. H.3840.

-20

vloIat1on of the statute, regardless of the standard of proof

appllcable ln constltutlonal challenges. See Senate Report

at 28:

the speclflc lntent of Lhls amendment 1s

that the plalntlffs may choose to establlsh

dlscrlmlnatory results wlthout .provlng any

klnd of dlscrlmlnatory purpo'se.

House Rep. No. 97-227, gTtr- Cong., lsL Sess., 29 (fgaf) (here-

lnaf|er "House Rep. "):

Sectlon 2 of H.R. 3112 w111 amend Sectlon 2

of the Act to make clear that proof of d1s-

crlmlnatory purpose or lntent 1s not required

1n cases brought under that provlslon.

The amendment of Sectlon 2 was lntended by Congress to

restore 1ts origlnal understandlng of the standard governlng

challenges to dlscrlmlnatory electlon practlces and procedures

whlch had been applled by the courts prlor to Clty of Mobl1e v.

Bolden. Both houses lndlcated that the statute, when enacted

1n 1965, dld not requlre proof of intentlonal dlscrlmlnatlon for

a vlolatlon, desplte lndlcatlons to the contrary 1n the p1urallty

oplnlon ln Clty of Mob1le v. Bolden, supra, 446 U.S. at 5f

( "th1s statutory provlslon (Sectlon 2) adds nothlng to the

appellee's Flfteenth Amendment c1alm"). See House Rep., 29:

I'The purpose of thls amendment to Sectlon 2 ls to restate Congress

earller lntent that vlolatlons of the Votlng Rlghts Aet, ln-

cludlng Sectlon 2, be establlshed by showlng the dlscrlmlnatory

effeci of the challenged practice.r' (Footnote omltted); Senate

Report , L7: "The Commltiee amendment reJ ecting a requlrement

that dlscrlmlnatory purpose be proved to establlsh a vlolatlon

of Sectlon 2 is fuI1y conslslent wlbh ihe origlnal legis1aClve

-30-

understandlng of Sectlon 2 when the Act was passed ln 1965.'r

Sectlon 2 embodles language taken dlrectly from @1!e

v. Regester, 4tZ U.S. 755, 766 (1973), whlch Congress lndlcated

correctly stated 1ts understandlng of the results siandard:

The plalntlffs I burden 1s to produce evldence

to support flndlngs that the politlcal pro-

cesses leadlng to nomlnatlon and electlon were

not equally open to partlclpatlon by the groups

1n questlon--that 1ts members had less opportunlty

than dld other resldents 1n the dlstrlcl to par-

tlclpate ln the political processes and io elect

leglslators of thelr cholce.

See Senate Report, 2B:

In adoptlng the rresults standardr as artlculated

1n Whlte v. Regester, the Commlttee has codlfled

tneffiin that case as lt was ap-

plled prior to the }Iob11e 11t1gation.

See House Report, 29-30:

By amending Sectlon 2 of the Act, Congress lntends

to restore the pre-Bolden understandlng of the

proper 1ega1 standaFililhfch focuses on the results

and consequences of an al1eged1y dlscrlmlnatory

votlng or electoral practlce rather than the lntent

or motlvatlon behlnd lt.

But, of course, regardless whether Congress was eorrect 1n lts under-

standlng of Che proof requlrements of Whlte v. Regester, or any

other pre-Bolden votlng rlghts cases, what ls relevant ls that

Congress enacted a statute whlch dlspensed wlth the requlremenL

of provlng any klnd of discrlmlnatory purpose to establlsh a

voilng rlghts v1oIat1on. Senate Report, 28; House Report, 2B-9.

Although the results standard of Section 2 derlves

from Congressr understandlng of the standard of proof ln Whltq

v. Regester, supra, Congress explleltIy provlded that',,he uest

for a statutory vlolatlon was slgnlf1cantly Clfferent from

that under the Constltution.

(a) As prevlously noted, proof of dlscrlmlnatory

purpose 1s not requlred to establlsh a vlolatlon of the

statute, regardless of the standard appllcable ln constltu-

tlonal challenges. Cf. clty of Moblle v. Bolden, supra,

446 U.S. at 59, quotlng Washlngton v. Davls, \26 U.S. 229,240

(LgT6), that "the lnvldlous quallty of a law clalmed to be

raclally discrlmlnatory must ultlmately be traced to a rac1al1y

dis crlmlnatory PurPose . tt

(b)UnresponslvenesslsnotanelementofaStatu-

tory vlolatlon, whatever 1ts relevance ln constltutlonal cases.

Indeed, Congress provlded, that the uSe of responslveness 1s

to be avolded, because 1t 1s a h1gh1y subJectlve factor whlch

creates lnconslstent results ln cases presentlng s1m11ar facts.

Senate Report 29, n. 115 ("The amendment reJects the rullng in

Lodge v. Buxton and companlon caseS that unresponslveness

1s a requlslte element.r'); House Report 29, n. 94, 30 ("The

proposed amendment avolds hlghly subJectlve factors such as

responslveness of elected offlclals to the mlnorlty communlty.tr)

In fact, responslveness 1S of no relevance even 1n rebuttal,

if plalntiff chooses not to offer evldence of unresponslveness.

Senate Report at 29, n. 116.

(c) Foreseeablllty of consequences, wh1le of

apparently doubtful relevance to a constltutlonal vlolatlon'

Clty of Mob11e ,r.-Epl9en, ggpge, t{46 U.S. at TL, n' L7, ls

rrqulte relevant elrldence of a statutory vloIation. " Senate

Report 27, n. f08.

(d) Whatever llmltations may exist on the scope

of the constltutlonal bar agalnst lndj-rect lnterference wlth

the rlght to vote, EE, e.8., City of Moblle v. Bo1den, su121'a,

4\6 U.S. at 65, and Rogers v. Lodge, _ U.S.

-,

I02 s.Ct.

3272, J2f6, n.5 (1982), Sectlon 2 embodles a functlonal vlew

of the politlcal process and prohlblts a very broad range of

lmpedlments to mlnorlty particlpatlon 1n the eleetorate. Senate

Report, 30, n. 120:

the coneluslon ln the Mob1le pIuraIlty

opinion that f there weFno-1nh1b1tlons

agalnst Negroes becomlng candldates, and

that, ln fact, Negroes had registered

and voted without hlnderancerr would

not be dlsposltlve. Sectlon 2, as amend-

ed, adopts the functlonal vlew ofrpolitical processr used in White rather

than the formallstlc vlew esffiGa Uy

the pIurallty 1n Mob1Ie. Likewise,

although the plurilIEy suggested that

the Flfteenth Amendment may be llmJ.ted

to the rlght to cast a bal1ot and may

not extend to clalms of votlng dllutlon,

thls sectlon wlthout questlon is almed

at dlscrlmlnatlon whlch takes the form

of d1Iut1on, as well as outrlght denlal

of the rlght to reglster or to vote.

The leglslatlve hlstory provides that to establlsh a

Section 2 v1oIat1on plaintlffs can show a varlety of factors,

lncludlng those derlved from the analytlcal framework used by

the Supreme Court 1n Whlte v. Rs.ges.!.er, and as artlculated in

subsequent d.eclslons such as Zlmmer v. McKelthen, 485 F.2d L297

(5tn Clr., 1973), aff 'd on other grouncis sub. nom. East Carco11

Parrlsh School Board v. Marshal, 424 U.S. 636 (L975) (per-curlam),

as follows:

33

(1) The extent of any hlstory of

offlclal dlscrlmlnatlon 1n the state

or po1ltlcal subdlvlslon that touched

the rlghts of the members of the mlnority

group to reglster, to vote, or otherwlse

to partlclpate in the democratlc process;

(2) The extent to whlch votlng 1n the

electlons of the state or polltlcal sub-

dlvlslon is raclally polarlzed;

(3) The extent to which the state or

po1itlcal subdlvlslon has used unusually

large electlon dlstrlcts, maJorlty vote

requirements, anti-slngle shot provlslons,

or other votlng practlces or procedures that

may enhance the opportunlty for dlscrlmlnatlon

agalnst a mlnorlty group;

(4) If there 1s a candldate slatlng

process, whether the members of the mlnorlty

group have been denled access to that process;

(5) The extent to whlch members of the

mlnorlty group ln the state or polltlcaL sub-

dlvislon bear the effects of dlscrlminatlon 1n

such areas as educatlon, employment and health,

whlch hlnder their ab11lty to partlclpate

effectlvely ln the poIltlcaI process;

(6) Whether pol1t1ca1 campaigns have been

charaeterized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

3t{

fi) The extent to whleh members of the

mlnorlty group have been elected to pubIlc

offlce 1n the Jurlsd1ct1on.

Senate Report, 28-9. These factors are the most lmportant ones 1n

evaluatlng whether or not black voters "have less opportunlty than

other members of the electorate to partlclpate 1n the poIltlcal

process and to eteet representatlves of thelr choicert' wlthln the

meaning of Sectlon 2.

There ls no requlrement under the statute that any

partlcular number of factors, however, be proved or that they

polnt one way or the other. t'The courts ordlnarlly have not used

these factors, nor does the committee lntend them to be used, as a

mechanlcal tpolnt countlngr devlce.rr Senate Report, 29, n. 118.

Instead, appllcatlon of Sectlon 2 requlres the trial courtts over-

aII Judgment, based on a totallty of the relevant facts and clrcum-

stances of the partlcular case, whether mlnorlty voters enJoy the

equal opportunl-ty to partlclpate ln the poI1tlca1 process and

elect representatlves of thelr choice.

In amendlng Sectlon 2, Congress thus lntended to

establlsh a rellabIe and obJectlve standard for adjudlcatlng votlng

rlghts vlolatlons. ft.indlcated that 1n determlnlng an overall

trresultrr of dlscrimlnatlon, based on the totallty of clrcumstances,

certaln types of objectlve, veriflable evldence should be emphaslzed

(such as an offlcial hlstory of dlscrlmlnatlon ln voti-ng, raclal

bloc votlng, use of a majorlty vote requlrement or other practices

known to enhance the opportunity for dlscrimlnatlon, the extent

of ninorlty offLee-holdlng and the present effects of discrlmlnation

-35

ln such areas as education, employnnent and health). Other 'uypes

of subjecblve and lmpresslonistic evldence were not regarded as

relevant or wei-ghty (such as unresponslveness), and no inference

of dlscrimlnatory purpose -- no matter how clrcumstantial ls

requlred. Recent eases applylng the analysls,of amended Sectj-on

2 to strlke down dilutlve votlng procedures lnclude Jones v.

Lubbock, C.A. No. 5-76-3\ (tt.0. Tex., Jan. 20, 1983), slip op.,

14 ( "Under the findlngs of the court wlth respect to the factors

whlch the Congress deemed to have been relevant to the determlna-

tion of this question, and under the totallty of all of the cir-

cumstances and evldence 1n thls case, lt is inescapable that the

at-Iarge system in Lubbock abrldges and dllutes mlnoritlesr oppor-

tunlties to elect members of their own cholce."); Thomasvllle

Branchof NAACP v. fhomas County, Georgia, Civ. No. 75-34-TH0M (M.D.

Ga. Jan. 26,1983); Perklns v. Clty of West Helena, Arkansas,675

F.2d 2or (Btn Cir. 1982), aff 'd, 5L U.s.L.I,'I. 3252 (Oct. lJ, r982);

Tayior v. Haywood County, Tenn., 544 F.Supp. L122, 1134-35 (W.D.

Tenn, l9B2) (applylng the Section 2 tactors and granting a prellmlnary

injunctlon agalnst use of at-Iarge votlng for the Haywood County

lllghway Commlssioners ) .

Act 20 results ln the denial or abrldgement of

laintiffsr rl tto vote ln v Iatlon of Sectlon 2

The record in

ihat Act 20 has a racrally

thls case clearly supports the conclusion

dlserlnlnatory resuit in vj_olation of

9 / The Couru should note that nelbher of the cases cited by defend-ants as havlng been decided after the L9B2 amend,ment to Seclion Zactual-ly involve claj-msof vote dilution und.er Sect j-on 2. In Rogers ,r.

lsggg, the Suprerne Court lnterpreted -"he Fourteench -Amendment-TilFhorc a charrenge to an at-large syste:r in Burke county, Georg'i a.. rn

Brant-Ley rr. Brown, 5:0 F.Supp. 490 (S.D. Ga. t982), Secticn 2 iras not

even pieaded in ihe ccmplaint.

^.- <r.,

Sectlon 2. The relevant record evldence has not been

serlously contested.

(a) There has been a long hlstory of offlclal

dlscrlmlnation agalnst blacks ln Loulslana and the New

Orleans metropolltan area involvlng registratlon and votlng,

lncludlng grandfather clauses, the white primary and under-

standlng tests.

(b) There 1s a clear pattern of racial bloc votlng

1n Orleans Parish electlons, in whlch correlatlons between the

race of the voter and the race of the candldate are extremely

high. There ls evidence to suggest a slmilar pattern of

polarization in the Jefferson Parlsh electorate.

(c) The evidence that blacks in the New Orleans

area are a distinct socio-economlc group and bear the present

effects of dlscrlminatlon ln such areas as educatlon and em-

ployment, was not contested, nor can the effect of these

condltj.ons as inhibitlng blacks equal participation in the

u-/politi-cal process be serlously contested.

L0/ The leglslatlve history provides where there is evldence

of dlsproportlonate educatlonal, employment, lncome leve1 and

1lvlng eondltlons, plalntlffs need not prove any caus.al nexus

betleen their dlsparate soclo-economlc status and thelr 1nab111ty

to partlclpate effecClvely ln 1ocaI pol1ties. Senate Rep., 29,

n. 1I4. See Whlte v. Regeter, supra, 412 U.S. at 768-69: "Theresldual ffi-affiory ieGcted itself ln the fact that

only five Mexlcan-Amerlcans since 18B0 have served 1n the

Texas legislature from tsexar County.'r1 and Klrksey v. Board of

Supervisors, 55\ F.2d 139, 145 (5tn Cir. f9re

Court and this Court have recognlzed that dlsproporrclcnareiT ef,uca-

tlonal, effployment, lnccme levei and Ilving conditions iend to

operate to deny access to poliiical life. In this case, the lower cotut

helci that these economic and educatlonal factors were not proved io

have rsi-gni-flcant effectr on pcliilcal access ln iij.nos Ccunty.

It ls not necessary i-n any case ihai --he mlnority prove such a

eausal llnk. Inequallty of access r-s an lnference irhicn fLows

frcm the exlstence of economic and educaEt-on inecual-ities. "

37

(d) No black has ever been elected to a statewide

posltlon ln Loulsiana. No black 1n this century has been

erected to congress from the State of Loulslana. Although

blacks are over 55% of the population ln Orleans parlsh, Iess

than L5% of the elected offlclals are black. No black has

been elected to any offlce from a multiparlsh dlstrlct wlth

slze, population and percentage of black registered voters

comparable to the Second congressj-onal Dlstrict under Act zo.

(e) Ir 1s undlsputed that Loulslana presently uses

a maJorlty vote requirement and has 1n the past emproyed votlng

practlces and procedures that enhance the opportunlty for d1s-

erlmination against mlnorltles. see Rogers v. Lodge, supra,

73 L.Ed.2d at 1023, 1024; White v. Regester, g!_pra, \LZ U.S. at

766 (majorlty vote requirementsrrenhance the opportunity for

racial dlscriminatlon."); city of Port Arthur v. united states,

_ U.S. _, 103 S.Ct. 530, 535 (1982) (',In the context of

racial bloc votlng the [majorlty vote] rule would permanently

foreclose a black candldate from belng electe<1 ?t \

(f) Prevlously adopted legistatlve reapportionment

criteria may falrly be sald to favor a majorlty black population

dlstrlct that respected orreans parlsh (po1lt1car) and the

l4ississippi River (natural) bound.aries, that placed. divergent com-

muniiles of lnterest ln dlfferent distrlcts and that was compact.

Accordlngly, the policy favoring the fraeturlng of the New Oi'leans

black populatlon eoncentratlon in a non-compact cistrict can

best be described as tenuous, further evidenclng a vioration of

Section 2. Senate Report , 29.

-J6-

The defendants appear to take the vlew that slmply

because blacks can reglster and vote 1n Loulslana wlthout

hlnd.rance, and have been elected to a few offlces 1n Orlians

Parlsh, there can be no d11utlon of mJ-norlty votlng strength.

Consequently, they vlrtually ignore the rlch evldence 1n the

record of rac1al bloc votlng, the depressed soclo-economlc

status of blacks, the contlnulng effects of past dlscrimlnatlon

and the other factors lndlcated by congress whlch show that an

electlon practlce results 1n the denlal or abrldgment of the

equal rlght to vote. This 11m1ted vlew has no basls in the

Iaw, the 1e91slat1ve history or prlor cases. Congress specl-

flcally rejected the vlew urged by defendants when it amended

and extended the Votlng Rights Act 1n 1982. Senate Report, 30,

n.120.

The dlscrlminatory rrresultsr test focuses on whether

the poI1tlca1 process, as 1i has worked, and as lt now promlses

to work, has made it equally posslble for mlnorlty voters to

partleipate 1n the polltlcal process and elect representatlves

of thelr cholce Co offlce. In a senser the process by whlch

the leglslature enacted Act 20, rejecting the textbook plan with a

maJorlty black dlstrlct, ls a mlcrocosm of the way the poIltical

process has worked to 11mlt the opportunlty of blacks to par-

tlcipate: fracturlng thelr voting strength, lgnorlng thelr

input, excluding thelr elected representatlves from meetings,

perpetuating the I'oId ord.ei'rr and lnhiblting the oppcr-

tunlty of black voters to elect a representatlve of thelr cholce

to Congress ln thls Century.

-39

3. Section 2, as amended, is a proper exercise of

congressional power to enforce, by appropriate

Iegislation, rights protected by the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments

In their post-trial memorandum, defendants contend for

the first time that Section 2 oversteps congressional

authority by modifying a constitutional standard. Defen-

dants are wrong. In view of the broad power that Congress

enjoys to enforce the substantive rights protected by the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments, the legislative history

of Section 2 makes it clear that the result standard of

proof of Section 2 does not overturn the Supreme Courtrs

decision in Mobile v. Bo1den, but is an expression of

Congress' enforcement power to end the perceived risk of

purposeful discrimination.

The Supreme Court, in an unbroken line of cases over

the past seventeen years, has affirmed that section 5 of the

fourteenth Amendment and section 2 of the fifteenth Amend-

ment invest Congress with broad powers to enforce the

substantive rights those amendments secure. South Carolina

v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (f965); Katzenbach v. Morgan,

384 U.S. 64I (1956); Oregon v. l'litcheI1, 400 U.S. 156

( 1980) ; City of Rome v. U.S. , 446 U.S. 156 ( 1980) .

In South Carolina v. Katzenbach the Supreme Court,

confronted squarely the constitutionality of major provi-

sions of the Voting Rights Act. The Court reviewed the

legislative history, noting that Congress had adopted the

- 40

Act because "sterner and more elaborate measures" were

necessary to combat the "unremitting and ingenious defiance

of the Constitution" by States which perpetuated the "insidious

and pervasive evil" of racial discrimination in voting. 383

U.S. at 309. Those "sterner" measures of the Act, the Court

heId, were an appropriate vehicle to enforce Congress' respon-

sibility as articulated in the fifteenth amendment. Section

2 of the fifteenth amendment conferred upon Congress "full

remedial powers to effectuate the constitutional prohibition

against racial discrimination in voting." Id. at 326.

Shortly thereafter, in Katzenbach v. Morgan, supra, the

Court addressed the scope of Congress' power to enforce the

fourteenth amendment. Rejecting a challenge to section 4(e)

of the Act on the ground that it exceeded Congress' fourteenth

amendment enforcement power, the Court held that such power

parallelled the power conferred upon Congress by the fifteenth

amendment, as delineated in South Carolina v. Katzenbach.

The Court stated that:

Correctly viewed, 55 is a positive grant of

Iegislative power authorizing Congress to exercise

its discretion in determining whether and what

legislation is needed to secure the guarantees of

the Fourteenth Amendment. 384 U.S. at 65I.

Congress' sweeping power to enforce the fourteenth and

fifteenth amendments, as articulated in South Carolina v.

Katzenbach and Katzenbach v. Morgan, was most recently

reaffirmed in City of Rome v. United StaLes, supra. In City

of Rome plaintiffs challenged, inter aIia, the constitutionality

- 4t

of Congress' power to enforce the fifteenth amendment by

enacting the preclearance provisions of the Act. Reiterating

its analysis of congressional power in South Carolina v.

Katzenbach and Katzenbach v. Morgan, the Court upheld the

'Act based on "Congress' broad. power-to enforce the Civil War

Amendments.'r 446 U.S. at 176. The Court surveyed the

analytical development of federalism doctrine in the context

of Congress' passage of the Voting Rights Act and concluded

that:

principles of federalism that might otherwj.se be

an obstacle to congressional authority are neces-

sarily overridden by the power to enforce the

CiviI War Amendments "by appropriate legisIation. "

Those Amendments were specifically designed as an

expansion of federal power and an intrusion of

state sovereignty. 446 U.S. at L79 (emphasis

added).

In amending section 2 Lo prohibit voting practices that

result in racial discrimination without requiring a showing

of intent, Congress concluded that to enforce fully the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments such a standard was

necessary and "appropriate legislation" to prevent purposeful

discrimination. In reaching this conclusion, Congress found

(f) that the difficulties faced by plaintiffs forced

to prove discriminatory intent create a substan-

tial risk that intentional discrimination will go

undetected, uncorrected and undeterred

(2) that vot,ing practices and procedures that have

discriminatory results perpetuate the effects of

past purposeful discrimination.

Senate Report at 40.

-42

Congress noted specifically in the legislative record

the fundamental defect in the intent standard of proof for

challenges to recent discriminatory enactments such as

reapportionment pIans. Senate Report at 37 . Congress was

concerned that plaintiffs challenging a redistricting plan

would be unable to overcome the ability of defendants to

create a documentary trail and to offer a non-racial

rationalization for a Iaw which, in factr purposefully

discriminates. As long as the Court must make an ultimate

finding of intent, even based on the circumstantial and

inferential factors of White v. Regester, the problem of

fabrication remains reaI. Senate Report at 37 .

The legislative record provided a concrete basis for

Congress to conclude generally that purposeful discrimina-

tion is difficult and costly to prove, and that purposeful

discrimination wiIl continue unabated as long as the intent

standard of proof remains the law. Therefore, in order to

enforce effectively the guarantees of the fourteenth and

fifteenth amendments, Congress rationally concluded that it

was necessary to prohibit voting practices with discrimina-

tory results. Senate Report at L7-39i H.R. Rep. No. 97-227,

97th Cong. Ist Sess. 29 (1981); see also Hearings on

Ext,ension of the Voting Rights Act, Subcommittee on Civil

and Constitutional Rights, House of Representatives, SeriaI

No. 24, Part 3 at 1999-2055, June 24, l98I; Hearings on S.

-43

L992 before the Subcommittee on the Constitu tion of the

Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 97th Cong. 2d Sess.,

Serial No. J-97-92, Vol. I at 952-973.

Nevertheless, defendants argue that because a plurality

of the Court held in I'lobile that section 2 is co-extensive

with the Fifteenth Amendment, Congress' amendment of section

2 Lo provide for a result standard of proof is outside the

limits of the Constitution, and effectively overturns the

Supreme Courtrs substantive interpretation of the fifteenth

amendment. Close scrutiny of the relevant Iegislative

history and the governing case law, however, reveals that

Congress was not seeking to overturn MobiLels holding

concerning the scope of the fifteenth amendment, but merely

attempting to exercise properly its broad powers to

guarantee the enforcement of constitutional rights under the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments.

The Iegislative history of section 2 explicitly states

that the amendment of section 2 is not an attempt to

override the Supreme Court's decision in Mobile v. Bolden by

statute; the Senate Judiciary Committee Report readily

acknowledges Congress' Iack of power Eo overturn the Supreme

Court's substantive interpretation of the Constitution.

Senate Report at 4I. The effort of Congress in enacting

section 2 was not to redefine the scope of constitutional

provisions, but to detach section 2 from its prior coexten-

- 44 -

sive status with the fifteenth amendment, and invest it with

the broad power Congress enjoys to enforce constitutional

rights beyond the minimum safeguards the Constitution itself

LL/provides . -'

In Lassiter v. Northampton County Board of Elections,

360 U.S. 45 (1959) the Supreme Court held that literacy

tests, if not employed in a discrininatory manner, did not

violate the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments. But in

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, supra and Katzenbach v. llorgan,

supra the Court rejected constitutional challenges to

Congress' ban on literacy tests in the Act, upholding

Congress' prohibition of literacy tests despite their facial

constitutionality. The Court was, therefore, permitting

Congress to enforce constitutional rights by enacting

legislation which exceeded the direct requirements of the

Constitution. fn response to the argument advanced by New

York State in Morgan, that the prohibition of literacy tests

could not be "appropriate" to enforce the fourteenth

amendment until the judiciary ruled that the statute was

prohibited by the fourteenth arnendment the Court stated:

LL/ The results standard of proof in section 2 is based on

the fourteenth amendment as well as the fifteenth amend-

ment. It is also an effort to return to the standard of

proof pre-l"lobi1e, which ref Iects Congress' original intent

in enacting section 2. See Senate Report at L5-27, discussed,

supra.

-45-

g,Ie disagree. Neither the language nor history of

55 supports such a construction. As we said with

regard to 55 in Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339,

..1345, "It is tne power oT eongress which has been

enlarged. Congress is authorized to enforce the

prohiUi tions by appropri.ate legislatioil-Sme